Abstract

We previously reported that mouse parotid acinar cells display an anion conductance (IATPCl) when stimulated by external ATP in Na+-free extracellular solutions. It has been suggested that the P2X7 receptor channel (P2X7R) might underlie IATPCl. In this work we show that IATPCl can be activated by ATP, ADP, AMP-PNP, ATPγS and CTP. This is consistent with the nucleotide sensitivity of P2X7R. Accordingly, acinar cells isolated from P2X7R−/− mice lacked IATPCl. Experiments with P2X7R heterologously expressed resulted in ATP-activated currents (IATP-P2X7) partially carried by anions. In Na+-free solutions, IATP-P2X7 had an apparent anion permeability sequence of SCN− > I− ≅ NO3− > Br− > Cl− > acetate, comparable to that reported for IATPCl under the same conditions. However, in the presence of physiologically relevant concentrations of external Na+, the Cl− permeability of IATP-P2X7 was negligible, albeit permeation of Br− or SCN− was clearly resolved. Relative anion permeabilities were not modified by addition of 1 mM Carbenoxolone—a blocker of Pannexin-1. Moreover, Cibacron Blue 3GA, which blocks the Na+ current activated by ATP in acinar cells but not IATPCl, blocked IATP-P2X7 in a dose-dependent manner when Na+ was present, but failed to do so in TEA+-containing solutions. Thus, our data indicate that P2X7R is fundamental for IATPCl generation in acinar cells and that external Na+ modulates ion permeability and conductivity as well as drug affinity in P2X7R.

Keywords: Salivary Glands, P2X7 Receptors, Anion Permeability, Fluid Secretion, ATP and Na+

Introduction

Adenosine 5′- triphosphate (ATP) acts as an external signaling molecule in a variety of tissues (for reviews see North, 2002 and Burnstock, 2007). Many of the cellular responses to external ATP are mediated by activation of either G-protein coupled metabotropic P2Y and/or ionotropic P2X purinoceptors present in the plasma membrane of cells in numerous tissues (Burnstock, 2007; North and Barnard, 1997; Ralevic and Burnstock, 1998). Epithelial cells express both P2Y and P2X receptors (Tenneti et al., 1998; Fukushi, 1999; Schwiebert and Zsembery, 2003; Li et al., 2003, Hayashi et al., 2005; Ma et al., 2006). While the detailed physiological role of these receptors remains unclear, it has been shown that external ATP induces multiple cellular events important to the functions of epithelia (Roman and Fitz, 1999; Leipziger, 2003). For example, external ATP increases both cationic and anionic conductances in the plasma membrane of epithelial cells (Leipziger, 2003; Li et al., 2005; Arreola and Melvin, 2003). Specifically, activation of P2Y receptors generates a G protein-coupled increase in InsP3 that leads to Ca2+ release from intracellular stores whilst activation of P2X receptor channels directly mediates Na+ and Ca2+ entry (for a complete review see Burnstock, 2007). The resulting increase in [Ca2+]i associated with activation of either class of P2 receptors is likely to be important for epithelial fluid secretion since Ca2+ induces opening of Ca2+-dependent Cl− and K+ channels which are key to initiate and to sustain fluid and electrolyte secretion (Melvin et al., 2005).

Salivary acinar cells express at least four different types of purinoceptors, P2Y1 and P2Y2 as well as P2X4 and P2X7 (Turner et al., 1999; Li et al., 2003) whose stimulation results in an increase in intracellular Ca2+ (McMillan et al., 1993). Although the physiological role of P2X4 and P2X7 ionotropic receptors expressed in these cells still remains unknown, it has been shown that stimulation of exocrine gland acinar cells with external ATP activates Ca2+-dependent ion currents (Li et al., 2003) including those associated with Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels. Additionally, in mouse parotid acinar cells bathed in Na+-free medium, external ATP activates a Ca2+-independent anion conductance named IATPCl (Li et al., 2005; Arreola and Melvin 2003). We found that the kinetics and channel pharmacology of IATPCl are different from other anion channels previously described in salivary gland acinar cells, including the Ca2+-dependent, ClC-2, CFTR and volume-sensitive Cl channels (Arreola and Melvin 2003; Zeng et al., 1997). Moreover, the P2X receptor antagonist Cibacron Blue 3GA (CB) did not block IATPCl when recorded in solutions containing TEACl and 0 Na+. In contrast, CB blocks the ATP-activated Na+ current presumably flowing through P2X receptors (Arreola and Melvin, 2003). Thus, we suggested that IATPCl has an anion conductance component with novel characteristics, including more sensitivity to Bz-ATP than ATP and resistance to the P2X receptor antagonist CB. Recently, Li et al. (2005), using acinar and duct cells from parotid glands of wild type and P2X7R−/− mice, suggested that IATPCl results from regulation of P2X7R by external Cl− and Na+. They also concluded that P2X7R are not permeable to Cl−. This study prompted us to further investigate the role of P2X7R in the generation of IATPCl using a pharmacological approach and P2X7R−/− mice. In addition, recombinant mouse P2X7R cloned from parotid acinar cells was used to determine if the resulting ATP-activated currents (IATP-P2X7) displayed anion permeability sensitive to CB and extracellular Na+ similar to IATPCl. Our data shows that P2X7R is essential for IATPCl generation, that IATP-P2X7 has indeed anion permeability similar to that of IATPCl and a conductivity which is modulated by extracellular Na+. Furthermore, CB blocks P2X7R when Na+ is present but in the absence of external Na+ CB potentiates the current through the receptor. Thus, our data indicate that P2X7R is fundamental for IATPCl generation and that the functional structure of P2X7R may be critically dependent on external Na+.

Methods

P2X7R−/− mice

P2X7R−/− mice were kindly provided by Dr. Christopher A. Gabel (Solle et al., 2001) and bred at the University of Rochester’s vivarium. Wild type (WT) C57BL/6J (Jackson Laboratories, ME) and P2X7R null mice age 2 to 6 months were used following protocols approved by the Animal Resources Committee of the University of Rochester.

Cloning of P2X7R and P2X4R from the mouse parotid gland

Total RNA was isolated from mouse parotid gland (RNEASY Mini Kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) followed by DNAse treatment. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the ISCRIPT cDNA synthesis kit (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA). Full-length cDNAs were amplified by PCR using the following gene specific primers:

P2X7R (accession no. NM_011027): 5′-GAA TTC GGC TTA TGC CGG CTT GCT GC-3′; 5′-CGG CTT TCA GTA GGG ATA CTT GAA GCC-3′

P2X4R (accession no. AF089751): 5′-CAT TAG AAT TCA CGA CGC GGA GCA GC-3′; 5′-CGA GAG AAT TCG GTT AGG CAT CAC TGG TC-3′

PCR products were isolated (PCR cleaning kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and their sequences verified. The 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of P2X7R and P2X4R contained EcoRI sites to facilitate insertion of each clone into a bicistronic expression vector (pIRES2-EGFP, Clontech), generating pIRES2-EGFP-P2X7R and pIRES2-EGFP-P2X4R vectors, respectively. In addition, the mouse P2X7R clone was inserted in an inverted fashion (pIRES2-EGFP-P2X7Rinv) into the pIRES2-EGFP vector as a negative control. The cDNA sequences obtained for mouse parotid P2X7R and P2X4R were identical to those previously published in the NCBI data base).

Biotinylation of Cell Surface Proteins

Biotinylation of cell surface proteins was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Parotid acinar cells were prepared as previously described (Evans et al., 1999). Briefly, C57Bl/6J +/+ and P2X7−/− mice were rendered unconscious by exposure to CO2 and killed by exsanguinations prior to isolation of cells by collagenase digestion. Dispersed cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS (pH 8.0) prior to the addition of 80 μl of 10 mM Sulfo NHS-SS-Biotin stock solution per ml of PBS. After 30 minutes at room temperature (22 °C), the reaction was stopped by addition of ice-cold 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) for 10 minutes, and then the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS.

Preparation of Crude and Affinity-enriched Plasma Membrane Proteins

Biotinylated cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,000g for 45 sec and the pellet resuspended in 5 ml of ice-cold homogenizing buffer containing: 250 mM sucrose (JT Baker; Philipsburg, NJ), 10 mM triethanolamine, leupeptin (1 μg/ml) and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (0.1 mg/ml). Cells were homogenized with ULTRA TURRAX T8 Homogenizer (IKA, Werke, Germany). Unbroken cells and nuclei were pelleted at 4,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was saved and the pellet resuspended and centrifuged in the same volume of homogenization buffer as before. The collected supernatants were pooled and centrifuged at 22,000g for 20 min at 4°C. The pellet was suspended in the same buffer and centrifuged at 46,000g (Beckman SS28 rotor) for 30 minutes at 4°C. The resultant crude pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of hypotonic buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (1 tablet/50 ml; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), 1mM Na3VO4 and 1 mM NaF, and then incubated with 200 μl of DYNABEADS M-280 streptavidin at 4°C overnight. Beads were collected with a magnetic plate and washed with hypotonic buffer to obtain the membrane associated fractions. The streptavidin beads carrying the enriched plasma membrane fractions were suspended in 100 mM DTT for 2 hr according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Dynal Biotech ASA, Oslo, Norway) and then centrifuged at 10,600g for 3 minutes. The supernatants were collected and used for electrophoretic analysis.

Electrophoresis and Western Blot Analysis

Protein (30 μg) was heated at 95°C for 5 minutes prior to separation in a 7.5% or 10% SDS-PAGE Tris-glycine mini-gel (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA). Protein was transferred onto polyvinylidene (PVDF) membranes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) overnight at 4°C using a transfer buffer containing 10 mM CAPS (3-[Cyclohexylamino]-1-propanesulphonic acid), pH 11 in 10% methanol. Membranes were blocked overnight at 4°C with 5% non-fat dry milk in 25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl (TBS) and then incubated with primary antibody for P2X7R (Millipore-Chemicon International Inc.; Temecula, CA) at a dilution of 1:300 in 2.5% non-fat dry milk solution at 4°C overnight. After washing with TBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBS-T), the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat-anti rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL) at a dilution of 1:2,500 in TBS-T/2.5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. Labeled proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL detection kit, GE-Amersham Biosciences; Piscataway, NJ).

Single parotid acinar cell isolation

Single acinar cells were isolated from wild type or P2X7R−/− mice parotid glands as previously described (Arreola et al., 1995). Briefly, glands were dissected from exsanguinated mice under CO2 anesthesia and minced in Ca2+-free minimum essential medium (MEM; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Fraction V, Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). The tissue was treated for 20 min (37°C) in MEM Ca2+-free solution containing 0.02% trypsin + 1 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) + 2 mM glutamine + 1% BSA. Digestion was stopped with 2 mg/ml of soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma Chemical, Saint Louis, MO) and the tissue further dispersed by two sequential treatments of 60 min each with collagenase (0.04 mg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) in MEM-Ca2+ free + 2 mM glutamine + 1% BSA. Dispersed cells were centrifuged and washed with basal medium Eagle (BME; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). The final pellet was resuspended in BME + 2 mM glutamine and cells plated onto poly-L-lysine-coated glass coverslips for electrophysiological recordings.

Culture and transient transfection of HEK-293 cells

HEK-293 cells (InVitrogen; Carlsbad, California, USA) were maintained in DMEM medium (Gibco, BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) at 37°C in a 95% O2/ 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were grown on 30 mm Petri dishes to 50-60% confluence and then transfected with either pIRES2-EGFP-P2X7R, pIRES2-EGFP-P2X4R or pIRES2-EGFP-P2X7RInv DNA (2 μg per dish of a 1 μg/μl stock) according to the manufacturer instructions using POLYFECT transfection reagents (Qiagen; Valencia, CA). Transfected cells were detached from culture dishes using trypsin, plated onto 5 mm glass coverslips and allowed to re-attach for at least 5 h before use.

Electrophysiological Recordings

A single coverslip containing either freshly isolated mouse parotid acinar or transfected HEK-293 cells was placed in a recording chamber mounted on the stage of a Nikon inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with UV illumination. EGFP fluorescence observed under blue light (~488 nm) illumination was used to identify transfected HEK-293 cells.

Currents were recorded at room temperature (20-22°C) using the conventional whole-cell patch-clamp configuration (Hamill at al., 1981) and an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments; Foster City, CA). Pipettes made with Corning 8161 glass (Warner Instruments Inc.; Hamden, CT) have a resistance between 3-4 MΩ when filled with pipette solutions. The standard pipette (internal) solution contained (in mM): TEA+(or Na+) Cl 140, EGTA 20, HEPES 20 (pH 7.3; tonicity was ~335 mosm/kg). Cells were bathed in a standard external solution containing (in mM): TEA+(or Na+) Cl 140, CaCl2 0.5, D-mannitol 100, HEPES 20 (pH 7.3; tonicity was ~375 mosm/kg). A 3 M KCl agar-bridge was used to ground a 300 μl recording chamber. The internal solution was Ca2+-free while the external was hypertonic to preclude activation of Ca2+-dependent and volume-sensitive chloride currents, respectively, which are endogenous to mouse parotid acinar and HEK-293 cells (Perez-Cornejo and Arreola, 2004; Hernandez-Carballo, et al., 2003). Tonicity of the solutions was determined using a vapor pressure osmometer (Wescor; Logan, UT).

Voltage ramps (from −100 to +100 mV in 1 s; every 2.5 seconds) were used to generate I-V curves and to estimate reversal potentials. To determine PTEA/PCl or PNa/PCl the external solutions were prepared as above with absolute TEACl or NaCl concentrations equal to (in mM): 35, 50, 70, 100 and 140 or 27, 53, 73, 93, 113, 133 and 153, respectively (internal [TEACl] or [NaCl] were fixed at 141 mM using the standard internal solutions). To assay the effects of external [Na+] on IATP-P2X7 Br− or SCN− permeation, a mole fraction experiment was performed in cells dialyzed with the standard TEA+ internal solution whilst keeping the total external cation concentration (Na+ + TEA+) = 140 mM. In these experiments, the pH of the external solution was adjusted to 7.3 with 20 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM CaCl2 was present and tonicity was adjusted to ~375 mosm/kg with D-mannitol. To determine the anion permeation of IATP-P2X7, Cl− was substituted with equimolar concentrations of SCN−, I−, NO3−, Br− or Acetate (supplied as TEA salts) in the standard external solution.

Adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), cytosine 5′-triphosphate (CTP), guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP), uridine 5′-triphosphate (UTP), adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP), adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP), adenosine (A), ATPγS, AMP-PNP, and TNP-ATP were added to the external solution at a final concentration of 5 mM, whereas NPE-caged ATP was added to a final concentration of 250 μM. After nucleotide addition the solution pH was readjusted to 7.3 with TEAOH or NaOH. Block of IATP-P2X7 by Cibacron Blue 3GA (CB) in the presence or absence of Na+ was evaluated constructing dose-response curves at +80 and −80 mV. Solutions were gravity-perfused at a flow rate of about 4 ml/min. Uncaging ATP was achieved by controlled photolysis using a pulsed Xenon arc lamp (T.I.L.L. Photonics, Eugene, OR) equipped with a fiber optic guide. The fiber optic was fed into an epifluorescence condenser attached to an inverted microscope. High intensity (80 J) 1-ms flashes of UV light (~360 nm) were applied to release the ATP.

Voltage commands were delivered from a holding potential of 0 mV. Data were acquired using the software Clampex 9.0 (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Unless otherwise indicated data were filtered at 5 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz.

Analysis

The anion permeability sequence of P2X7R was determined performing standard protocols of ion substitution to determine reversal potential (Er) shifts. These Er values were plugged into the Goldman, Hodgkin and Katz (GHK) equation to estimate the apparent permeability of each anion relative to Cl−. This technique has been extensively applied to determine selectivity of ion channels (Hille, 2001). Since the purinoceptor channel is mainly permeable to cations (North, 2002; Coutinho-Silva and Persechini, 1997; Duan et al., 2003), we first determined the relative permeability of the major cations present in our external recording solutions (TEA+ and Na+) relative to Cl− and subsequently used these values to determine an apparent permeability ratio to different anions.

PTEA/PCl or PNA/PCl ratios were separately determined by analyzing the effects of different external [TEACl] (with internal [TEA] = 141 mM) or different external [NaCl] (with internal [NaCl] = 141 mM), on the raw reversal potentials using the GHK equation:

| (1) |

where [C+]e or [C+]i represent the external or internal concentration of either [TEA+] or [Na+], PC and PCl represent TEA or Na and Cl permeabilities, respectively, and R, T and F have their usual thermodynamic meanings.

Next, using the reversal potential shifts (ΔEr) induced by replacing Cl− in the standard external solution with anion X and the PTEA/PCl determined from equation 1, an apparent permeability ratio for each anion relative to Cl− (PX/PCl) was then estimated using another form of GHK equation:

| (2) |

where [TEA+]i is the intracellular [TEA+] = 141 mM, [X−]e is the external SCN−, I−, NO−3, Br−, or acetate concentration (140 mM), and [Cl−]e = 140 mM. Thus, these apparent permeability ratios would be valid only for 141 mM internal TEACl conditions. Measurements of Er were also carried out in the presence of 1 mM carbenoxolone (CBX). CBX was dissolved in water and then added to the extracellular solution. In these experiments the cells were first pre-incubated for 5 minutes with CBX and CBX was present throughout the experiment.

Liquid junction potentials (LJP) were measured for the standard external TEACl solution and for TEA solutions where Cl− was substituted by SCN−, I−, NO3−, Br− or Acetate (Table 1). Membrane potential values were not corrected by LJP and the resulting selectivity sequence estimated as above described is not altered by LJP.

Table 1. Apparent anion permeability of IATP-P2X7.

Shifts in reversal potential induced by anion substitution in Na+-free, TEA-containing solutions were used with equation 2 to determine PX/PCl. The term PTEA/PCl, which is present in equation 2, was determined from the data in Figure 4 as described in the text. Er= reversal potential of the current; n= number of cells tested. Liquid junction potentials are listed for different anion substitution solutions. The −0.6 mV listed in the Cl− row is the potential measured upon returning to the standard external solution after the anion substitution measurement. ND = Not determined.

| Anion | Er (mV) Without CBX |

Er (mV) With 1 mM CBX |

PX/PCl Without CBX |

Liquid Junction Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCN− | −17.69±0.49 n=11 |

−19.01±1.52 n=6 |

7.31±0.14 | −1 |

| I− | −8.69±0.46 n=11 |

−8.17±0.79 n=6 |

3.28±0.16 | −1.3 |

| NO3− | −7.46±0.40 n=11 |

ND | 2.83±0.16 | +1.5 |

| Br− | −4.77±0.47 n=10 |

ND | 1.97±0.15 | −0.3 |

| Cl− | −1.75±0.22 n=12 |

−3.05±0.86 n=6 |

1 | −0.6 |

| Acetate | +5.18±0.86 n=10 |

+12.22±3.57 n=6 |

~0.0±0.00 | +2.9 |

Dose-response curves for ATP, ADP and CB blockade in the presence of Na+ were fitted to a Hill equation:

| (3) |

where Rmax and Rmin are the maximum or minimum percentage of response or block, [A] is either external ATP or ADP concentration, [CB] is the CB concentration, EC50 and IC50 are [A] or [CB] to get 50% of maximum response or block, and n is the Hill coefficient.

Experimental data are presented as the mean ± SEM. EC50, IC50 and n values were obtained from fitting average data, and no errors are given. The statistical significance between groups was evaluated applying one-way ANOVA and the post-hoc Scheffé test (p<0.05).

Materials

Most of the chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical (Saint Louis, MO) including (Tris)2 or Na2 salts of CTP, UTP, GTP, ATP, ADP, AMP, Adenosine, ATPγS, AMP-PNP and TNP-ATP, NPE-caged ATP, Carbenoloxone, unless as indicated in the text. EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin [Sulfosuccinimidyl-2-(biotinamido) ethyl-1,3-dithiopropionate] was from Pierce (Rockford, IL) and M-280 streptavidin beads were from Dynal Biotech ASA (Oslo, Norway).

Results

Pharmacology of IATPCl and IATP-P2X7

We have previously shown that ATP or Bz-ATP stimulation of voltage clamped single parotid acinar cells (dialyzed and bathed in TEA+ containing solutions with 0 Na+) induces the appearance of a Ca2+-independent ion current (referred to as IATPCl) that is partially carried by anions (Arreola and Melvin, 2003). We suggested that IATPCl resulted from activation of a novel Cl− conductance in parotid acinar cells, although recent data indicate that the ATP-activated currents, including IATPCl, are due to activation of cation-selective P2X7 receptors (Li et al., 2005). This prompted us to further evaluate the role of P2X7R in the generation of IATPCl. We reasoned that if P2X7R are responsible for IATPCl then both currents, IATPCl and IATP-P2X7 (current through P2X7R expressed in HEK-293 cells and activated by ATP) should have similar pharmacological sensitivity and ion permeability characteristics.

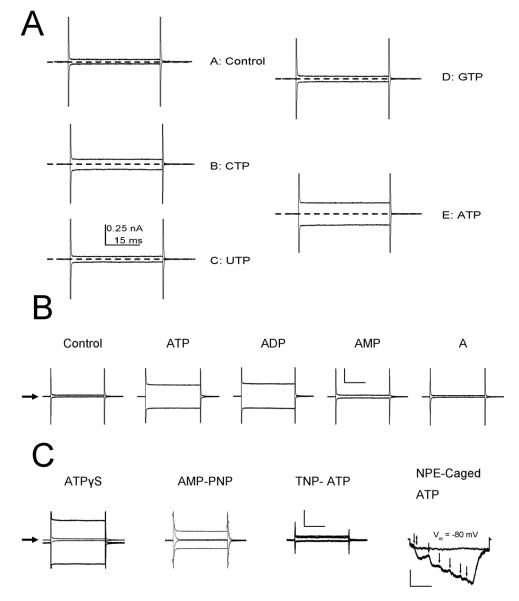

The ability of a wide variety of nucleotides and ATP derivatives to activate IATPCl was tested by application of a single concentration (5 mM). A summary of these responses is presented in Figures 1A and B, which show representative raw traces obtained at +80 and −80 mV from a single acinar cell bathed in a standard external solution containing either 0 or 5 mM of the indicated nucleotides or ATP derivatives. IATPCl was readily activated by ATP and partially by CTP (panel A). Other nucleotides like GTP and UTP did not significantly activate the current. Raw traces in panel B show that ADP was the only ATP derivative which activated IATPCl, while AMP and adenosine failed to activate the current. Since ADP was able to activate IATPCl, we investigated whether metabolization of ATP to ADP was necessary for IATPCl activation. Figure 1C shows that AMP-PNP and ATPγS, two non-hydrolysable ATP analogs were able to activate IATPCl. Hence, ATP hydrolysis is not required for IATPCl activation. As expected, the antagonist TNP-ATP failed to activate the current. To further support the idea that ATP per se activates IATPCl, the external [ATP] was rapidly increased by applying UV light flashes to an extracellular solution containing 250 μM NPE-caged ATP. Figure 1C (rightmost traces) shows that a single UV flash (double head arrow) applied in the absence of caged-ATP did not activate IATPCl (flat trace). However, addition of 250 μM NPE-caged ATP (arrowheads) to the same cell resulted in current activation (stair-like trace) after application of UV flashes. Collectively, these results suggest that ATP per se is sufficient to activate IATPCl.

Figure 1. Activation of IATPCl by trisphosphate nucleotides and ATP derivatives. A.

Raw current traces obtained from a single representative acinar cell stepped during 50 ms to −80 or +80 mV in the absence (control) or presence of 5 mM CTP, UTP, GTP or ATP. All currents were recorded using a standard internal solution that contained (in mM): 140 TEACl, 20 EGTA and 20 HEPES (pH 7.3), while the external solution contained (in mM): 140 TEACl, 0.5 CaCl2, 100 D-mannitol and 20 HEPES (pH 7.3). Dotted lines indicate zero current level. B. Raw traces recorded from a representative single acinar cell (n=5) stepped for 50 ms to −80 and +80 mV in the absence (control) or presence of 5 mM ATP, ADP, AMP and Adenosine (A). Calibration bars: 0.5 nA, 15 ms. C. Representative traces obtained in the absence (traces of smaller amplitude) and in the presence of 5 mM of the non-hydrolysable ATP analogs ATPγS (n=3) or AMP-PNP (n=3) and of 5 mM of the P2 receptor blocker TNP-ATP (n=3). The slight shift from 0 current level in ATPγS was the result of using (Na+)2-ATP salt to activate the current. Calibration bars: 0.5 nA, 15 ms.NPE-Caged ATP: representative traces of a single cell stepped to −80 mV (n=4). Flat trace: The cell was initially exposed to short UV flash (double head arrow) in the absence of NPE-caged ATP (no response), then exposed to 250 μM NPE-caged ATP (no response). Stair-like trace: UV flashes (arrows) were applied in the presence NPE-caged ATP. Current returned to control level by perfusing the bath with the standard external solution. Calibration bars: 0.1 nA, 10 ms. Black arrows on the left side indicate zero current levels in all cases.

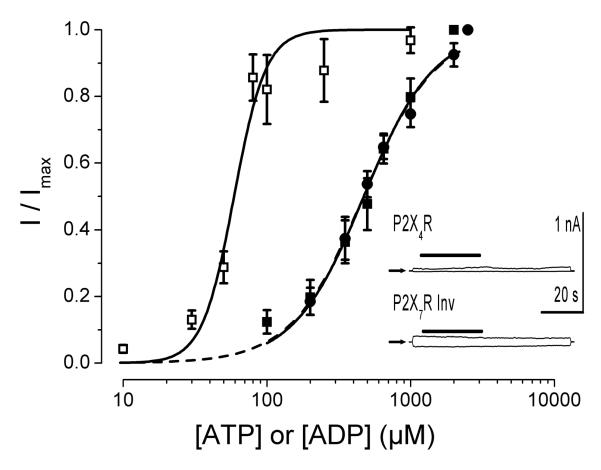

Our previous dose-response experiments done using 0 Na+, TEA+-containing solutions showed that ATP activates IATPCl in acinar cells with an EC50 of 158±10 μM and a Hill coefficient of 3.4±0.4 at +80 mV (Arreola and Melvin, 2003). Data in Figure 1A show that ADP was able to activate IATPCl. Consequently, we carried out whole-cell recordings under the same experimental conditions with P2X7R cloned from the mouse parotid gland and expressed in HEK-293 cells to test the ability of external ATP and ADP to activate IATP-P2X7 and to determine whether or not P2X7R alone is sufficient to account for the dose-response curve observed in acinar cells. The resulting IATP-P2X7 dose-response curve to ATP obtained in Na+-free, TEA-containing external solution is depicted in Figure 2 (open squares). The EC50 value estimated from fit with equation 3 was 59 μM with a Hill coefficient of 4 at +80 mV (n=7). Similarly, the IATP-P2X7 dose-response curve to ADP performed using 0 Na+, TEA+-containing external solutions (Fig. 2, closed symbols) shows that ADP activates IATPCl in acinar cells (closed circles; n=5) as well as IATP-P2X7 in HEK-293 cells (closed squares; n=8) with EC50 values of 469 and 472 μM, and Hill coefficients of 1.7 and 1.8, respectively. Thus, IATP-P2X7 and IATPCl are equally sensitive to ADP (472 vs. 469 μM), but IATP-P2X7 is approximately 2.7 fold more sensitive to ATP than IATPCl (59 vs. 158 μM). We don’t know the reason for this discrepancy but acinar cells express both P2X4 and P2X7 receptors in an unknown ratio and this could contribute to changes in ATP sensitivity. In addition, a higher ecto-nucleotidase activity in acinar cells compared to HEK-293 cells could also contribute to change the apparent ATP sensitivity of endogenous channels (Henz et al., 2006). Control experiments show that HEK-293 cells transfected with either P2X4 or an inverted sequence of P2X7 did not exhibit the ATP-activated current (inset in Figure 4).

Figure 2. Dose-response curves for ATP and ADP.

Dose-response curves of P2X7R expressed in HEK cells to ATP (□) or ADP (■) and of IATPCl recorded from a single acinar cell exposed to ADP (•). Continuous lines are fits with Eq. 3 to data, from these fits EC50 and Hill coefficients were obtained. These values correspond to 59 μM and 4 (□), 469 μM and 1.7 (■), and, 472 μM and 1.8 (•), respectively. Internal solution (in mM): 140 TEACl, 20 EGTA and 20 HEPES (pH 7.3). External solution (in mM): 140 TEACl, 0.5 CaCl2, 100 D-mannitol and 20 HEPES (pH 7.3). Inset: Negative controls, showing that cells transfected with either P2X4R or inverted P2X7R displayed no currents when exposed to 5 mM ATP (bars) in the same conditions used for P2X7R. Zero current level is indicated by arrows.

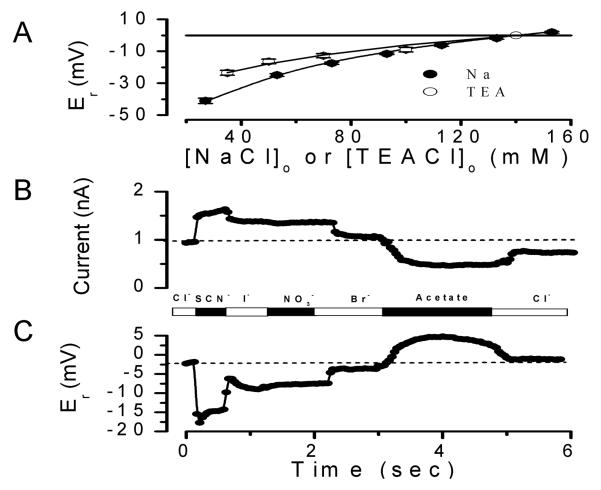

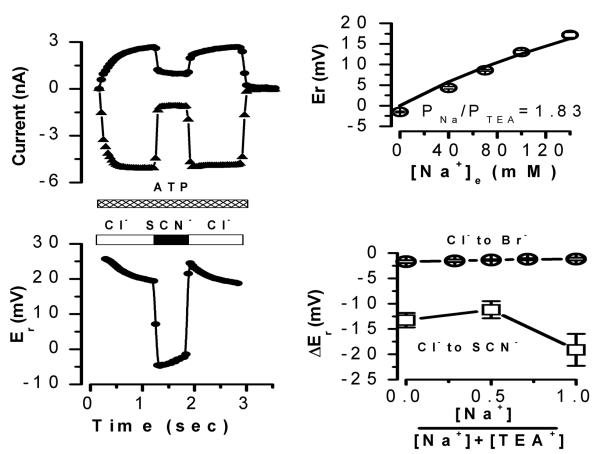

Figure 4. Anion permeability of IATP-P2X7. A.

The reversal potential of the current activated by 5 mM ATP(Tris)2 was measured in the presence of different external concentrations of NaCl (•, n=6) or TEACl (○, n=8). The internal solution contained (in mM): NaCl 141 or TEACl 141, EGTA 20 and HEPES 20. The external solution contained (in mM): CaCl2 0.5, D-mannitol 100, HEPES 20 and TEACl 35, 50, 70, 100 and 140 or NaCl 27, 53, 73, 93, 113, 133 and 153, respectively. Continuous lines are fits with Eq. 1 to the data, which gave PTEA/PCl = 6.17 (○) and PNa/PCl=4.5×10−3 (•). B. Representative time course (n=10) of current amplitude measured at +80 mV. C. Corresponding time course for reversal potential values (n=10) measured from the current shown in panel B. Current was activated by perfusion of standard external solution (140 mM TEACl−) containing 5 mM ATP(Tris)2. Then, in continuous presence of ATP, Cl− ions were replaced by 140 mM SCN−, I−, NO3−, Br− or acetate (supplied at TEA salts) at the times indicated by the bars. Dotted lines indicate the current amplitude or reversal potential levels in the presence of 140 mM Cl−. Internal solution (in mM): EGTA 20, HEPES 20 and TEACl 140; external solutions contained (mM): CaCl2 0.5, D-mannitol 100, HEPES 20 and TEACl 140.

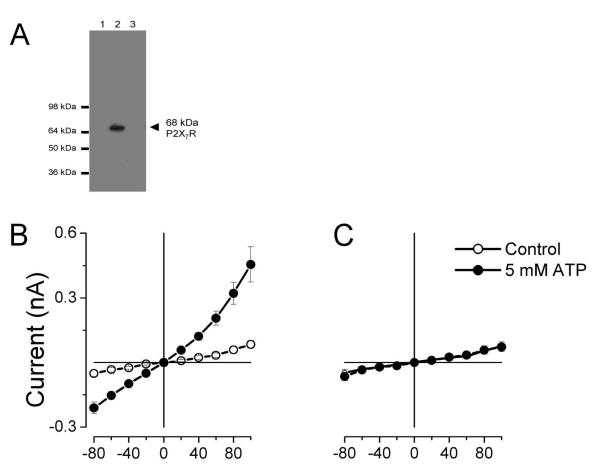

P2X7R is essential for IATPCl activation in parotid glands

P2X7 receptors appear to be essential for IATPCl generation in acinar cells (Li et al., 2005). However, our previous data show that IATPCl was insensitive to block by Cibacron Blue 3GA (CB), a known P2X receptor antagonist (Arreola and Melvin, 2003). Hence for completeness we corroborate the findings of Li and coworkers using mice lacking expression of P2X7R. Figure 3A shows the results of a western blot for P2X7R carried out using biotinylated membranes isolated from parotid glands. Lane 1 contains size markers, lane 2 and 3 contain membranes isolated from WT and P2X7R−/− mice, respectively. The 68 kDa band corresponding to P2X7R was absent in membranes from P2X7R−/− mice but is present in membranes from WT mice. Since the P2X7R is absent in the knock out mouse we then isolated single parotid acinar cells from WT and P2X7R−/− mice to functionally analyze the effect of P2X7R ablation on IATPCl. Figure 3B demonstrates that extracellular ATP significantly increased the current amplitude (filled circles) above basal levels (open circles) in WT acinar cells at all potentials tested. Both current amplitude and current-voltage relationship were comparable to those previously reported (Arreola and Melvin, 2003). In contrast, IATPCl was absent in acinar cells from P2X7R −/− mice (Fig. 3C) thus supporting the idea that P2X7R is essential for IATPCl generation.

Figure 3. P2X7R are necessary for IATPCl generation.

Presence of P2X7R was detected in biotinylated membranes isolated from parotid glands from WT and P2X7R−/− mice (A). Samples were run in a 7.5 % SDS-PAGE gel. Lane 1 contains SeeBlue Plus2 Pre-Stained Standard, lane 2 contains membranes from WT mice (50 μg of protein) and lane 3 contains membranes from knock-out mice (50 μg of protein). Current-voltage (I-V) relationships were constructed with currents recorded from acinar cells isolated from WT (B; n=5) or P2X7R −/− mice (C; n=8) in the absence (open circles) or presence (closed circles) of 5 mM (Tris)2-ATP. Currents were generated by application of 50 ms voltage steps from −80 to +100 mV in 20 mV increments and then measured near the end of each step. Currents were recorded using an internal solution that contained (in mM): 140 TEACl, 20 EGTA and 20 HEPES (pH 7.3); the external solution contained (in mM): 140 TEACl, 0.5 CaCl2, 100 D-mannitol and 20 HEPES (pH 7.3).

Na+ effect on P2X7R anion permeation

The anion selectivity sequence determined for IATPCl from reversal potential shifts was SCN−> I− > NO3− > Br− > Cl− > glutamate (Arreola and Melvin, 2003). Since our experiments with KO mice indicated that P2X7R expression is essential for IATPCl generation in freshly dissociated acinar cells, we hypothesized then that both conductances, IATPCl and IATP-P2X7, should display the same or fairly similar anion selectivity sequence. Previous studies in other preparations showed that P2X7R are cation-selective channels with little or no anion permeability (Virginio et al., 1999), yet other studies reported anion permeability in P2X7R-expressing cells (Coutinho-Silva and Persechini, 1997; Duan et al., 2003). To quantitatively establish if P2X7R are permeable to both anions and cations we used the standard Goldman-Hodgkin and Katz (GHK) equation to analyze anion substitution experiments (Hille, 2001). The GHK equation allowed us to determine the permeability coefficients of TEA+ and Na+ relative to Cl−, since TEA+ and Na+ are both permeable through P2X7R. Therefore, we independently evaluated PTEA/PCl and PNa/PCl ratios from measurements of reversal potential values obtained at various external [TEACl] and [NaCl]. We then used these permeability ratios to determine an anion selectivity sequence from anion substitution experiments, as described in Methods.

The relative permeability ratio PNa/PCl for mouse P2X7R was determined in whole-cell experiments by varying [NaCl] in the external solution and keeping [NaCl] at 140 mM in the pipette solution. PTEA/PCl was determined in a similar experiment, in this case TEACl was used in the bath and pipette solutions instead of NaCl. Figure 4A shows that reduction of both of [NaCl] and [TEACl] in the bath shifted the reversal potentials to negative values, which indicates that cationic conductances dominate IATP-P2X7. The effect of external [NaCl] on the reversal potentials (filled circles) was fit with Equation 1 (solid line) and a PNa/PCl value of 220 was obtained. Equally, shifts in reversal potentials obtained using TEACl (open circles) were fit with Equation 1 to obtain a PTEA/PCl =6.17. Hence, P2X7R has a significant Cl− permeability in the presence of TEA+ but little in the presence of physiologically relevant Na+ concentrations.

Once PTEA/PCl was estimated as required by Equation 2, we proceeded to determine the anion selectivity sequence of P2X7R in cells bathed and dialyzed with solutions containing TEA+. In these experiments external Cl− was replaced with equimolar concentrations of SCN−, I−, NO3−, Br− or acetate under continuous stimulation with 5 mM ATP(Tris)2. If P2X7R channels are indeed anion permeable, then the reversal potential of the current activated by external ATP will shift according to the permeability of the anion being tested (Hille, 2001). Figure 4 shows a representative time course where both current amplitude at +80 mV (panel B) and the corresponding reversal potential (panel C) of the current activated by ATP were continuously monitored in the same cell. Substitution of Cl− with SCN−, NO3−, I− and Br− increased the current amplitude while acetate decreased it. Cl− substitution by other anions resulted in a sudden shift in Er, which was fully reversibly upon returning to Cl− containing media. This indicates that P2X7R display significant anion permeation. Anions that induced larger shifts in the reversal potential induced larger outward current amplitude variations, indicating that the anions with the higher permeabilities also have higher conductivities. These results are in complete agreement with the anion permeability of IATPCl in parotid acinar cells (Arreola and Melvin, 2003). Shifts in reversal potential induced by anion substitutions together with the PTEA/PCl ratio already determined (PTEA/PCl=6.17, Figure 4A) and Equation 2 were then used to estimate apparent permeability ratios for these anions with respect to Cl−. Table 1 summarizes the apparent anion permeability sequence for P2X7R: SCN− > I− ≅ NO3− > Br− > Cl− > acetate. This sequence is identical to that determined in native mouse parotid acinar cells (Arreola and Melvin, 2003).

The above data show that P2X7R supports significant anion currents in Na+-free, TEA+-containing media. However, as shown in Figure 4A the P2X7R conductance in Na+-based solutions can be totally attributed to Na+ with negligible Cl− contribution. The Na+-dependent modulation of permeation observed in the case of Cl− could be a phenomenon applicable to other anions too. To test this idea the external Cl− was replaced by SCN− and both the current and reversal potential were determined. Figure 5A and B show the time course of this response recorded from a representative cell. Time courses at −80 and +80 mV show that SCN− unexpectedly reduces current amplitude and produces a big change in reversal potential (about −25 mV for this cell), which indicates that SCN− is highly permeable even in the presence of external Na+. Despite this, SCN− has a smaller conductivity in the presence of Na+ than in the presence of TEA+. This modulation by Na+ of anion permeation posed the next question: is the ion permeability of P2X7 a function of Na+ concentration? Thus, we performed mole fraction experiments where the external Na+ was changed while the total monovalent cation concentration (Na+ + TEA+) was kept at 140 mM. Figure 5C displays the measured reversal potentials recorded with the mole fraction solutions containing 100% Cl−. The data can be fit with equation 4:

| (4) |

where [TEA]e represents the external [TEA+] and [Na]e represents the external [Na+]. From this fit (continuous line) a PTEA/PCl ratio of 3.64 and a PNa/PCl ratio of 7.7 were estimated, these values are smaller than those obtained using either TEA+ or Na+ alone. If we assume that the ion fluxes are independent the PNa/PTEA value expected should be around 36 but instead it falls around 2.1. Furthermore, when we plotted the expected reversal potential values assuming independent fluxes (PTEA/PCl = 6.17 and PNa/PCl = 220) against the [Na]e, we saw that the experimentally values fall far away (Figure 5C, broken line). Thus, presumably ions flow in a non-independent manner. Finally, the effects of external Na+ on anion permeability were subsequently determined from mole fraction experiments where the external [Cl−] was replaced with either Br− or SCN−. Figure 5D displays the reversal potential shifts induced by replacement with Br− (open circles) or SCN− (open squares). Both anions induced clear reversal potential shifts that were comparable to those observed in anion substitution experiments when 140 mM external TEA+ was present (see Figure 4 and Table 1). This result demonstrates that in the presence of external Na+ P2X7R is permeable to Br− and SCN−. The shifts induced by these anions were nearly independent of the Na+ mole fractions. A −11.2 mV shift was induced by SCN− when a mixture of 50% Na+ + 50% TEA+ was used. This shift is equivalent to a PSCN/PCl = 3.5, calculated using:

| (5) |

where [SCN]e is the external SCN− concentration (140 mM), PTEA/PCl = 3.64 (Figure 5D), and ΔEr is the shift in reversal potential induced by SCN−. PSCN/PCl value is ~ 2 fold smaller than that obtained in 0 Na+, TEA+-containing media (Table1).

Figure 5. Na+-dependent modulation of anion permeability in IATP-P2X7. A.

Representative time course (n=5) of current amplitude measured at +80 mV (○) or −80 mV (Δ) activated by application of 5 mM ATP(Tris)2 (as indicated by the striped bar) in external solutions containing Cl− or SCN− supplied as Na+ salts. B: Corresponding reversal potential time course (n=5) of the current activated by ATP shown in panel A. C: Reversal potentials of IATP-P2X7 in the presence of the different external [Na+]. The total concentration of Na+Cl + TEA+Cl was equal to 140 mM (n=4). Data were fit with Eq. 4 (see text) with PTEA/PCl ratio of 3.64 and a PNa/PCl ratio of 7.7. Broken line represents expected reversal potential values for PTEA/PCl (6.17) and PNa/PCl (220) plotted against the [Na]e. D: Shift in reversal potential of IATP-P2X7 (ΔEr) upon complete substitution of 140 mM Cl−e with Br− (○, n=4) or with SCN- (□, n=5) in the presence of different Na+ /(Na+ + TEA+) fractions. Pipette solution was the standard internal solution (140 mM TEACl). Each external mole fraction solution contained Na-X and TEA-X, where X represents either Cl− or Br− or SCN− (concentrations of CaCl2, D-mannitol and HEPES were kept as in the standard external solution). IATP-P2X7 was activated by 5 mM ATP(Tris)2 in the presence of Cl− and then switched to Br− or SCN−.

Is Pannexin-1 involved in the anion permeation induced by activation of P2X7R?

The newly discovered Pannexin-1 is a ubiquitous protein that associates with P2X7R. Long stimulation of P2X7R with ATP results in Pannexin-1 activation, which forms a macropore (Locovei et al., 2007; Pelegrin and Suprenant, 2006) permeable to large cations and anions. Therefore we asked: can the cation and anion permeability above described be attributed to Pannexin-1? To test this idea, we repeated our experiments in the presence of a supramaximal concentration of Carbenoxolone (1 mM), a drug that blocks Pannexin-1 with an EC50 of 2-4 μM (Pelegrin and Suprenant, 2006). Our results show that in Na+-free, TEA-containing bath solutions the values of IATP-P2X7 current reversal potential obtained in the presence different anions were not modified by the presence of 1 mM Carbenoxolone (Table 1). Thus, under our experimental conditions the macropores formed by Pannexin-1 are not the pathway for anion permeation.

Na+-dependence of P2X7R block by Cibacron Blue

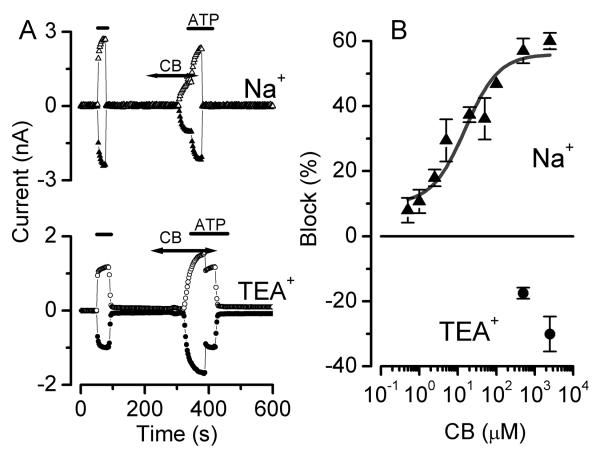

The above data show that the permeation and conduction of anions resulting from P2X7R activation is controlled by external Na+ as exemplified by the loss of Cl− permeability and the decrease in SCN− permeability in Na+-containing solutions (Figure 4A and Figure 5C, respectively). Others have previously shown that the rate of uptake of the large dye YO-PRO-1 (Virginio et al., 1999; Jiang et al., 2005) and the increase in NMDG+ permeability through P2X7R (Jiang et al., 2005) vary inversely with the [Na+]e. Also, recently a “Na+ memory” has been postulated to explain changes in permeability of this receptor in parotid gland cells (Li et al., 2005). All these observations suggest that the presence of external Na+ modulates different functional properties of P2X7R and may also modulate its response to blockers such as Cibacron Blue (CB). This Na+-dependent modulation may explain the apparent contradiction regarding CB: our data strongly indicates that both IATPCl and the Na+ current activated by ATP in acinar cells are mediated by P2X7R, however, CB did not block IATPCl while it did block the Na+ current activated by ATP in acinar cells (Arreola and Melvin, 2003). Could the external Na+ also modulate the CB blockade? To investigate this possibility we constructed for IATP-P2X7 dose-response curves of the block by CB in the presence of 140 mM Na+e or 140 mM TEA+e (0 Na). Our rationale was that CB interacts with an external binding site on P2X7R to produce its blocking effect. Consequently, if the structure of the receptor in the presence of physiological concentrations of Na+ is different from that in the presence of TEA+, then the ability of CB to block the receptor may be compromised in the presence of TEA. Experiments started with an initial ATP stimulus applied in absence of CB followed by a 1 min wash period. Subsequently, the desired CB concentration was applied, followed by a second ATP application in the continuous presence of CB. ATP application continued after removal of the blocker to evaluate the reversibility of the blockade. This protocol was repeated with each desired CB concentration. Figure 6A shows the time courses of the current amplitudes recorded at +80 and −80 mV from two representative cells bathed and dialyzed with either Na+ (upper panel) or TEA+ (lower panel) and exposed to ATP and ATP+CB. Amplitudes of the response to the first and second ATP stimulus (after CB washout) were similar and the averaged amplitude was taken as 100 % when calculating the percentage of block for different CB concentrations. In the presence of Na+, 500 μM CB reduced the current amplitude to a similar extent at +80 and −80 mV (about 53 %), suggesting that the blocking effect of CB is voltage independent. Figure 6B shows a dose-response curve to CB obtained in the presence of Na+ (closed triangles). The percentage of IATP-P2X7 block vs [CB] could be readily described by Equation 3 with an IC50 of 17.6 μM and a maximum blockade of 64.4 %. Conversely, concentrations as high as 2.5 mM CB failed to inhibit the current when the experiments were carried out in the presence of TEA+ (Fig. 6A, lower time course). In fact, the presence of 2.5 mM CB consistently enhanced the current activated by ATP to a similar extent at +80 and −80 mV and this enhancement was rapidly washed out upon removal of CB (note the drop in current when CB is removed in the presence of ATP). Figure 6B (closed circles) shows that 0.5 and 2.5 mM [CB] enhanced P2X7R current (current enhancement is represented as negative block % values) at +80 mV by 18 ± 2 % (n=4) and 30 ± 5 %, respectively (n=3). Thus, our data suggest that when the P2X7R is exposed to an external solution containing TEA+ and 0 Na+, the CB binding site is altered by some conformational change in the receptor protein precluding CB blockade.

Figure 6. Block of IATP-P2X7 by Cibacron Blue is Na+-dependent. A.

Time course of P2X7R current amplitudes recorded at +80 (open symbols) and −80 mV (filled symbols) in cells dialyzed and bathed with solutions containing 140 mM NaCl (triangles, upper panel) or 140 mM TEACl (circles, lower panel). Black lines indicate application of 5 mM ATP(Tris)2 and double arrowhead lines indicate application of 0.5 mM or 2.5 mM CB (in the presence of Na+ or TEA+, respectively). B: Dose-response curve of CB blockade obtained in NaCl (triangles) or TEACl conditions (circles). The number of cells tested were 4, 4, 5, 4, 3, 5, 2, 7, 3 for 0.1, 1, 10, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000 and 2500 μM CB, respectively. For the experiments in TEA+ only two high-concentration data points are plotted: 1000 (n=4) and 2500 (n=3). Continuous line is the fit with Eq. 3 and yielded an EC50=3.9 μM with maximum block of 64 % and a Hill coefficient= 0.5. Note that CB stimulates P2X7R currents in cells dialyzed and bathed in Na+-free solutions containing 140 mM TEA+ (filled circles).

Discussion

The results presented here and those previously published (Arreola and Melvin, 2003) show that IATPCl and IATP-P2X7 exhibit similar pharmacology. In acinar cells IATPCl is activated by Bz-ATP>ATP>ADP, similarly IATP-P2X7 in HEK-293 cells is activated by ATP>ADP. Additionally, 5 mM AMP-PNP and ATPγS did activate IATPCl while 5 mM CTP induced only partial activation. Other nucleotides and ATP metabolites, such as GTP, UTP, AMP and Adenosine were unable to activate IATPCl. With the exception of ADP and Bz-ATP, these compounds were not tested on heterologously expressed P2X7R in this work. However, the ability of the above mentioned agonists to activate IATPCl resembles their ability to activate P2X7R as reported by others (North, 2002; Ferrari et al., 1999; Solini et al., 1999; Hugel and Schlichter, 2000; Lambrecht, 2000; Idzko et al., 2001; Panenka, 2001; Budagian et al., 2003; Inoue et al., 2005). Our work also verify that P2X7R generate IATPCl in mouse parotid acinar cells since IATPCl is absent in P2X7R−/− mice (see also Li et al., 2005).

However, a question remains: does P2X7 underlie by itself IATPCl? There are at least two possibilities for the role of P2X7R in IATPCl generation. One possibility is that P2X7R may be part of a multiprotein complex which comprises an anion channel that gains its sensitivity to ATP through P2X7R. In fact, P2X7R have been shown to associate at the molecular level with several proteins, including laminin α3, integrin β2, β-actin and α-actinin, among others (Kim et al., 2001), but none of them form an ion pathway to support ion fluxes. However, prolonged stimulation of P2X7R with external ATP in Na+-free solutions are known to induce the formation of “macropores”. These macropores allow permeation of large cationic and anionic molecules (up to 900 Da) including NMDG+, TEA+, YO-PRO, ethidium bromide, anionic Fura-2 and Lucifer Yellow (Coutinho-Silva and Persechini, 1997; Steinberg et al., 1987; El-Moatassim et al., 1990; Persechini et al., 1998; Di Virgilio et al., 2001). Recently, it has been reported that Pannexin-1—a plasma membrane protein that bears some similarities with gap junction-forming proteins innexins and connexins—could form large nonselective pores that activate subsequently to P2X7R stimulation since inhibition of Pannexin-1 prevents the cellular uptake of large molecules (Locovei et al., 2007; Pelegrin and Suprenant, 2006). Is Pannexin-1 the anionic pore of IATPCl? According to our experiments this doesn’t seem to be the case since the ATP-induced anion permeability was not modified by the presence of 1 mM carbenoxolone, a blocker of Pannexin-1. Same concentration of carbenoxolone efficiently inhibited the ATP-induced ethidium bromide uptake in HEK-293 cells transfected with mouse P2X7R (data not shown) indicating that Pannexin-1 was indeed blocked. A second possibility for the role of P2X7R is that P2X7 itself could grant both ATP sensitivity and anion selectivity to IATPCl.. In other words, after activation with external ATP and in the absence of Na+ the anions go through the P2X7R pore. So far, our results support this latter alternative which was suggested by previous reports (Egan et al., 2006; Ruppelt et al., 2001; Bo et al., 2003; Duan et al., 2003). Thus, the native IATPCl in mouse parotid acinar cells may reflect the passage of anions through P2X7R as it has been shown for P2X5R in developing chick skeletal muscle (Hume and Thomas, 1988; Thomas and Hume 1990). This idea is also supported by the data showing that IATP-P2X7 resulting from the heterologous expression of mouse P2X7R produces an IATPCl-like current. Both IATPCl and IATP-P2X7 share the same anion selectivity sequence and similar Na+-dependent actions of CB (see also Arreola and Melvin, 2003).

Data presented here show that conductivity and permeation to anions in P2X7R are both modulated by external Na+. In the absence of Na+ PCl>0 but in Na+-containing solutions PCl was near 0. Morever, PSCN/PCl was ~ 2 fold larger in TEA+ than in Na+-containing media but its conductivity was smaller in Na+ than in TEA+. Nevertheless, the anion permeability sequence of P2X7R determined in the absence of Na+ was the same as that determined for IATPCl in native acinar under the same conditions (Arreola and Melvin, 2003). In these experiments, reducing the total external salt concentration changes the ionic strength of the solution (but not its tonicity, since this was adjusted to ~375 mosm/kg by addition of appropriate amounts of D-Mannitol; see Methods) and might indirectly alter the apparent ionic conductivity and/or selectivity. However, the same manipulation was used in the Na+ and TEA+ experiments, so changing the ionic strength is unlikely to have a major effect on the apparent ionic conductivity and/or selectivity. Although under physiological conditions (with Na+ present in the external medium) such anionic permeability through P2X7R would be minimal, nevertheless, this could be important for some critical cellular functions. For example, after ATP stimulation a small anionic permeability through P2X7R provide a route for the release of the neurotransmitter glutamate in native astrocytes (Duan et al., 2003).

In addition, the blockade of IATP-P2X7 was also dependent on external Na+. When Na+ was present, P2X7R was blocked by CB (64% maximum blockade) but when Na+ was absent, CB rather than having an inhibitory effect potentiated IATP-P2X7. This observation and those previously described indicate that external Na+ modulates the ability of P2X7R to interact with CB and anions. This Na+ dependence of P2X7R maybe explained if the receptor has at least two different conformations. When Na+ is present, the P2X7R conformation would have available an external CB binding site outside the electrical field. In the absence of Na+ and presence of large cations such as NMDG+ or TEA+, the P2X7R would transit to a different conformation—still gated by ATP or ADP—, permeable to cations and anions whose conductivity is enhanced by CB. A simple switch from inhibition to enhancement on a drug effect is already suggestive of a structural change in the drug receptor site and this could also explain why CB blocks the ATP-activated current in parotid acinar cells only when Na+ was present (Arreola and Melvin, 2003). Alternatively, this modulation by Na+ could be through an allosteric mechanism as is the case for kainate receptors, which are modulated by Na+ and Cl− ions. These receptors have a Cl− binding site at the dimer interface that stabilizes the structure and allows receptor activation (Plested and Mayer, 2007; Plested and Mayer, 2008). Since our data does not provide a mechanistic explanation for P2X7R modulation by Na+ this remains as attractive avenue to explore in future work.

In conclusion, this work shows that: 1) the P2X7R is essential for IATPCl activation in mouse parotid acinar cells; 2) Na+ regulates anion conductivity and permeation in P2X7R, i.e. in the absence of Na+ and after stimulation with ATP the P2X7R become more permeable to anions; 3) Na+ regulates the effect of CB on P2X7R, i.e. CB inhibits or enhances P2X7R current in the presence or absence of Na+, respectively; and, 4) in the presence of physiologically relevant Na+ concentrations the P2X7R displays negligible Cl− permeability.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laurie Koek, Jennifer Scantlin, Mark Wagner, Carmen Y. Hernandez-Carballo and Monica Reyna for technical assistance. We also thank Dr. Ted Begenisich for his critical reading and comments on this work. This work was supported in part by grants from NIH, (DE09692 and DE13539 to JEM), and from CONACyT, Mexico (42561 to JA).

References

- 1.Arreola J, Melvin JE. A novel chloride conductance activated by extracellular ATP in mouse parotid acinar cells. J. Physiol. 2003;547:197–208. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.028373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arreola J, Melvin JE, Begenisich T. Volume-activated chloride channels in rat parotid acinar cells. J. Physiol. 1995;484:677–687. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bo X, Jiang LH, Wilson HL, Kim M, Burnstock G, Surprenant A, North RA. Pharmacological and biophysical properties of the human P2X5 receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:1407–1416. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budagian V, Bulanova E, Brovko L, Orinska Z, Fayad R, Paus R, Bulfone-Paus S. Signaling through P2X7 receptor in human T cells involves p56lck, MAP kinases, and transcription factors AP-1 and NF-kappa B. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:1549–1560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnstock G. Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:659–797. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coutinho-Silva R, Persechini PM. P2Z purinoceptor-associated pores induced by extracellular ATP in macrophages and J774 cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:C1793–C1800. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.6.C1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Virgilio F, Chiozzi P, Ferrari D, Falzoni S, Sanz JM, Morelli A, Torboli M, Bolognesi G, Baricordi OR. Nucleotide receptors: an emerging family of regulatory molecules in blood cells. Blood. 2001;97:587–600. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan S, Anderson CM, Keung EC, Chen Y, Swanson RA. P2X7 receptor-mediated release of excitatory amino acids from astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:1320–1328. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01320.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egan TM, Samways DSK, Li Z. Biophysics of P2X receptors. Pflugers Arch. – Eur. J. Physiol. 2006;452:501–512. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Moatassim C, Mani J, Dornand J. Extracellular ATP−4 permeabilizes thymocytes not only to cations but also to low-molecular-weight solutes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;181:111–118. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90251-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans RL, Bell SM, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE, Melvin JE. Targeted Disruption of the Nhe1 Gene Prevents Muscarinic Agonist-induced Up-regulation of Na+/H+ Exchange in Mouse Parotid Acinar Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274(41):29025–29030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrari D, Stroh C, Schulze-Osthoff K. P2X7/P2Z purinoreceptor-mediated activation of transcription factor NFAT in microglial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13205–13210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukushi Y. Heterologous desensitization of muscarinic receptors by P2Z purinoceptors in rat parotid acinar cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;364:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakman B, Sigworth F. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi T, Kawakami M, Sasaki S, Katsumata T, Mori H, Yoshida H, Nakahari T. ATP regulation of ciliary beat frequency in rat tracheal and distal airway epithelium. Exp. Physiol. 2005;90(4):535–544. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.028746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henz SL, Ribeiro CG, Rosa A, Chiarelli RA, Casali EA, Sarkis JJ. Kinetic characterization of ATP diphosphohydrolase and 5′-nucleotidase activities in cells cultured from submandibular salivary glands of rats. Cell Biol. Int. 2006;30:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez-Carballo CY, Perez-Cornejo P, Arreola J. Regulation of volume-sensitive chloride channels by H+ and Cl− ions in HEK 293 cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 2003;122:31a. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hille B. Ion channels of excitable membranes. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hugel S, Schlichter R. Presynaptic P2X receptors facilitate inhibitory GABAergic transmission between cultured rat spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:2121–2130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02121.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hume RI, Thomas SA. Multiple actions of adenosine 5′-triphosphate on chick skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 1988;406:503–524. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Idzko M, Dichmann S, Panther E, Ferrari D, Herouy Y, Virchow C, Jr., Luttmann W, Di Virgilio F, Norgauer J. Functional characterization of P2Y and P2X receptors in human eosinophils. J. Cell Physiol. 2001;188:329–336. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue K, Denda M, Tozaki H, Fujishita K, Koizumi S, Inoue K. Characterization of multiple P2X receptors in cultured normal human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005;124:756–763. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang LH, Rassendren F, Mackenzie A, Zhang YH, Surprenant A, North RA. N-methyl-D-glucamine and propidium dyes utilize different permeation pathways at rat P2X7 receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 2005;289:C1295–C1302. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00253.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim M, Jiang LH, Wilson HL, North RA, Surprenant A. Proteomic and functional evidence for a P2X7 receptor signaling complex. EMBO J. 2001;20:6347–6358. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambrecht G. Agonists and antagonists acting at P2X receptors: selectivity profiles and functional implications. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;362:340–350. doi: 10.1007/s002100000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leipziger J. Control of epithelial transport via luminal P2 receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 2003;284:F419–F432. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00075.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q, Luo X, Muallem S. Regulation of the P2X7 receptor permeability to large molecules by extracellular Cl− and Na+ J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:26922–26927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Luo X, Zeng W, Muallem S. Cell-specific behavior of P2X7 receptors in mouse parotid acinar and duct cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:47554–47561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma W, Korngreen A, Weil S, Cohen EB, Priel A, Kuzin L, Silberberg SD. Pore properties and pharmacological features of the P2X receptor channel in airway ciliated cells. J. Physiol. 2006;571(Pt 3):503–517. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMillan MK, Soltoff SP, Cantley LC, Rudel RA, Talamo BR. Two distinct cytosolic calcium responses to extracellular ATP in rat parotid acinar cells. Brit. J. Phamacol. 1993;108:453–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melvin JE, Yule D, Shuttleworth TJ, Begenisich T. Regulation of fluid and electrolyte secretion in salivary gland cells. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 2005;67:445–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.041703.084745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.North RA, Barnard EA. Nucleotide receptors. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1997;7:346–357. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panenka W, Jijon H, Herx LM, Armstrong JN, Feighan D, Wei T, Yong VW, Ransohoff RM, MacVicar BA. P2X7-like receptor activation in astrocytes increases chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression via mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7135–7142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07135.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Pannexin-1 couples to Maitotoxin- and Nigericin-induced Interleukin-1β release through a dye uptake-independent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282(4):2386–2394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pérez-Cornejo P, Arreola J. Regulation of Ca2+-activated chloride channels by cAMP and CFTR in parotid acinar cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;316:612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Persechini PM, Bisaggio RC, Alves-Neto JL, Coutinho-Silva R. Extracellular ATP in the lymphohematopoietic system: P2Z purinoceptors and membrane permeabilization. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1998;31:25–34. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1998000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plested AJR, Mayer ML. Structure and mechanism of kainate receptors modulation by anions. Neuron. 2007;53:829–841. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plested AJR, Mayer ML. Allosteric ion binding sites in kainate receptors. Biophys. J. Abstracts. 2008:362a–363a. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roman RM, Fitz JG. Emerging roles of purinergic signaling in gastrointestinal epithelial secretion and hepatobiliary function. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:964–979. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruppelt A, Ma W, Borchardt K, Silberberg SD, Soto F. Genomic structure, developmental distribution and functional properties of the chicken P2X5 receptor. J. Neurochem. 2001;77:1256–1265. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwiebert EM, Zsembery A. Extracellular ATP as a signaling molecule for epithelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1615:7–32. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solini A, Chiozzi P, Morelli A, Fellin R, Di Virgilio F. Human primary fibroblasts in vitro express a purinergic P2X7 receptor coupled to ion fluxes, microvesicle formation and IL-6 release. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:297–305. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solle M, Labasi J, Perregaux DG, Stam E, Petrushova N, Koller BH, Griffiths RJ, Gabel CA. Altered cytokine production in mice lacking P2X7 receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:125–132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinberg TH, Newman AS, Swanson JA, Silverstein SC. ATP4− permeabilizes the plasma membrane of mouse macrophages to fluorescent dyes. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:8884–8888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tenneti L, Gibbons SJ, Talamo BR. Expression and trans-synaptic regulation of P2X4 and P2z receptors for extracellular ATP in parotid acinar cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:26799–26808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas SA, Hume RI. Permeation of both cations and anions through a single class of ATP-activated ion channels in developing chick skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 1990;95:569–590. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turner JT, London LA, Gibbons SJ, Talamo BR. Salivary gland P2 nucleotide receptors. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1999;10:210–224. doi: 10.1177/10454411990100020701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Virginio C, MacKenzie A, North RA, Surprenant A. Kinetics of cell lysis, dye uptake and permeability changes in cells expressing the rat P2X7 receptor. J. Physiol. 1999;519:335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0335m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng W, Lee MG, Yan M, Diaz J, Benjamin I, Marino CR, Kopito R, Freedman S, Cotton C, Muallem S, Thomas P. Immuno and functional characterization of CFTR in submandibular and pancreatic acinar and duct cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1997;273:C442–C455. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]