Abstract

Objective

To estimate six-month prevalence of multiple substance use disorders (SUDs) among juvenile detainees by demographic subgroups (sex, race/ethnicity, age).

Method

Participants were a randomly selected sample of 1829 African American, non-Hispanic white and Hispanic detainees (1172 males, 657 females, ages 10–18). Patterns and prevalence of DSM-III-R multiple SUDs were assessed using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC 2.3). We used 2-tailed F- and t-tests with an alpha of 0.05 to examine combinations of SUDs by sex, race/ethnicity, and age.

Results

Nearly half of detainees had one or more SUDs; over 21% had two or more SUDs. The most prevalent combination of SUDs was alcohol and marijuana use disorders (17.25% females, 19.42% males). Among detainees with any SUD, almost half had multiple SUDs. Among detainees with alcohol use disorder, over 80% also had one or more drug use disorders. Among detainees with a drug use disorder, approximately 50% also had an alcohol use disorder.

Conclusions

Among detained youth with any SUD, multiple SUDs are the rule, not the exception. Substance abuse treatments need to target detainees with multiple SUDs who, upon release, return to communities where services are often unavailable. Clinicians can help ensure continuity of care by working with juvenile courts and detention centers.

Keywords: juvenile detainees, substance use disorders

INTRODUCTION

Substance use disorders (SUDs) in adolescents are a serious public health concern. Nearly one in four youth in community populations has an alcohol disorder, a drug disorder, or both (Turner and Gil, 2002; Warner et al., 1995). Risk of SUDs is even higher among troubled youth -- homeless youth, school dropouts, and those with mental health disorders (Aarons et al., 2001; Gilvarry, 2000) -- many of whom cycle through the juvenile justice system. On a typical day, approximately 109,000 youth are in custody (Sickmund et al., 2002); as many as two thirds of them may have one or more SUDs (Aarons et al., 2001; Otto et al., 1992; Teplin et al., 2002).

Among adolescents who abuse substances, multiple SUDs are common (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry [AACAP], 1997; Deas et al., 2000). Among 12–17 year old adolescents in the general population, 21% of those who abused substances had two or more SUDs (Kilpatrick et al., 2000). Among youth in substance abuse treatment, up to two thirds had at least two SUDs (Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2001a; Office of Applied Studies [OAS], 2001); among youth in alcohol treatment, over 80% had at least one other SUD (Martin et al., 1993).

Multiple SUDs are a challenge to psychiatry. Compared to individuals with one disorder, those who have multiple SUDs have greater treatment needs, are more recalcitrant to treatment, have higher dropout rates, and are more likely to relapse (Almog et al., 1993; Cohen, 1981; Rounsaville et al., 1987; Rowan-Szal et al., 2000). Abusing multiple substances also poses significant health risks: overdose, suicide, aggression, violent behavior, and other psychopathology (Cohen, 1981; Hubbard, 1990; Rounsaville et al., 1987)

Juvenile detainees are an important group to study for three reasons. First, multiple SUDs appear to be common among juvenile detainees. Prior studies suggest that as many as one half of serious juvenile offenders have multiple SUDs (McManus et al., 1984). Second, detained youth are captive and potentially amenable to intervention. Finally, because most detained youth are eventually released, sound data on juvenile detainees will help improve interventions for high-risk youth in the community.

Despite the need for data on multiple SUDs in juvenile detainees, there have been few studies. Although Dolamanta et al. (2003) provide some information on the prevalence of overlapping alcohol and drug use disorders, they did not examine these patterns by sex, race/ethnicity and age. Other available studies of incarcerated and detained delinquents provide some information about multiple SUDs, but many have one or more of the following methodological limitations:

Small samples. Previous studies did not have samples large enough or diverse enough to compare rates by sex, race/ethnicity, and age (Gibbs, 1982; Jackson, 1992; McKay et al., 1992; McManus et al., 1984; Milin et al., 1991).

Non-representative samples. Previous studies included few females (Jackson, 1992; Milin et al., 1991; Neighbors et al., 1992), included only violent detainees (McManus et al., 1984), or included only offenders with known or suspected SUDs (Milin et al., 1991; Neighbors et al., 1992).

Non-standard measures of substance use disorder. Many studies measure substance use, not disorder (Dembo et al., 1988; Gibbs, 1982; Jackson, 1992; McKay et al. 1992), and definitions of “use” vary across studies.

We present six-month prevalence of multiple SUDs in a random sample of 1829 juvenile detainees. Our sample is large enough to examine key demographic subgroups; SUDs are determined by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC), a widely used and reliable measure of SUDs.

METHOD

Participants and Sampling Procedures

Participants were 1829 males and females, 10–18 years old, randomly sampled at intake into the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center (CCJTDC) from November 1995 through June 1998. The sample was stratified by sex, race/ethnicity (African American, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic), age (10–13 years of age or 14 years and older), and legal status (processed as a juvenile or as an adult) to obtain enough participants in key subgroups, e.g., females, Hispanics, and younger children.

Participants were interviewed in a private area, almost always within two days of intake. Most interviews lasted two to three hours, depending on how many symptoms were reported. Interviewers were trained for at least a month; most had a Master's degree in psychology or an associated field and experience interviewing high risk youth. One third of our interviewers were fluent in Spanish. Detainees were eligible to be sampled regardless of their psychiatric morbidity, state of drug or alcohol intoxication, or fitness to stand trial.

Of the 2275 names selected, 4.2% (34 youth and 62 parents or guardians) refused to participate. There were no significant differences in refusal rates by sex, race/ethnicity, or age. Twenty-seven youth left the detention center before we could schedule an interview; 312 were not interviewed because they left while we were attempting to locate their caretakers for consent. Eleven others were excluded: nine became physically ill during the interview and could not finish it, one was too cognitively impaired to participate, and one participant was uncooperative with the interviewer.

We excluded an additional 55 participants because data necessary to diagnose substance use disorder were missing. There were no significant differences among these 55 cases by sex, race/ethnicity, or age at p=.05 in bivariate analyses. In most cases, these missing data were the functional impairment items of the DISC; our decision to exclude these cases may lower the estimates of the prevalence of SUDs.

All available cases were used for each reported diagnosis. Our final sample size is 1774. This sample size allowed us to reliably detect (i.e., distinguish from zero) disorders that have a base rate in the general population of 1.0% or greater with a power of .80 (Cohen, 1988).

The final sample comprised 1143 males (64.4%) and 631 females (35.6%), 980 African Americans (55.24%), 289 non-Hispanic whites (16.29%), 503 Hispanics (29.35%), and 2 “others” (0.11%). The mean age of participants was 14.9 years, and the median age was 15; age range was 10–18. (Additional information on our methods is available from the authors, and from Abram et al., 2003; Teplin et al., 2002).

Measures and Definitions

We used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) Version 2.3, (Bravo et al., 1993; Shaffer et al., 1996), the most recent English and Spanish versions then available. The DISC is highly structured, contains detailed symptom probes, has acceptable reliability and validity (Fisher, 1993; Piacentini et al., 1993; Shaffer et al., 1996), and requires relatively brief training. The substance use module of the DISC assesses the presence of DSM-III-R alcohol, marijuana, and other drug abuse and dependence in the past six months. The other drug category of the DISC 2.3 includes seven classes of illicit drugs: “uppers” (e.g. speed, amphetamines), “downers” (e.g. sleeping pills, barbiturates), other tranquilizers (e.g. diazepam [Valium®], chlordiazepoxide [Librium®]), opiates (e.g. heroin, opium, methadone, codeine), cocaine or crack, hallucinogens (e.g. LSD, peyote, PCP, etc.), and inhalants (e.g. glue, solvents).

We defined multiple SUD as two or more substance use disorders assessed by the DISC 2.3 within the six months prior to the interview.

Data Analysis

Data reduction

Each of the three DISC substance categories (alcohol, marijuana, and other drug) has three possible diagnoses (abuse, dependence, and no disorder). Thus, there are 27 possible combinations of SUD diagnoses (33 =27). Before analyzing the data, we first determined the best typology of SUDs, that is, the most common combinations. We investigated two questions:

Should we combine abuse and dependence?

Only 2.36% of the sample had alcohol abuse, 6.10% had marijuana abuse, and 0.39% had other drug abuse; in contrast, 22.77% had alcohol dependence, 38.34% had marijuana dependence, and 2.27% had other drug dependence. Because so few participants had a diagnosis of abuse, we combined abuse and dependence for each type of substance (alcohol, marijuana, and other drug). To confirm that combining abuse and dependence did not obfuscate important differences, we also analyzed the data combining no disorder and abuse and compared this grouping to those with a diagnosis of dependence only. These analyses were substantially similar to those presented here (available from the authors).

What is the best typology?

We used loglinear and latent class models (Agresti, 1990) to empirically identify the most common combinations of alcohol, marijuana, and other drug use disorders. We confirmed these findings using cluster analysis (Blashfield and Aldenderfer, 1988). Our analyses resulted in a mutually exclusive, five-category typology of common combinations of alcohol, marijuana and other drug use disorders: Group 1 = no disorder, Group 2 = alcohol use disorder only, Group 3 = marijuana use disorder only, Group 4 = both alcohol and marijuana use disorders, and Group 5 = other illicit drug use disorders inclusive of alcohol or marijuana. In other words, Group 5, comprises all participants meeting criteria for the DISC 2.3 other drug use disorder, whether or not they also had alcohol and/or marijuana use disorders.

Statistical Techniques

Because the sample is stratified by sex, race/ethnicity, and age, we weighted all estimates to represent the population of the detention center during the period of the study; all inferential statistics were corrected for sample design using the Taylor series linearization. We used 2-tailed F- and t-tests with an alpha of 0.05 to examine combinations of SUDs by sex, race/ethnicity, and age. We used Fisher's method to protect against Type I error. That is, we report tests of significance for specific contrasts of race/ethnicity and age only when the overall test was significant (Snedecor and Cochran, 1980). We report disorders for males and females separately because combining these groups masks important differences.

RESULTS

Prevalence of SUDs in the detained population (N=1774)

Sex differences

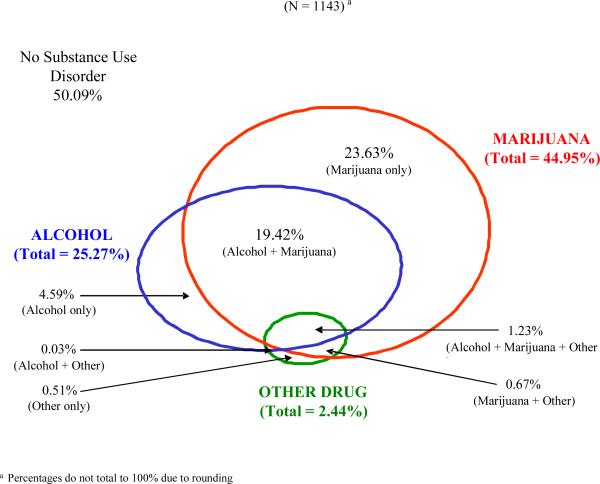

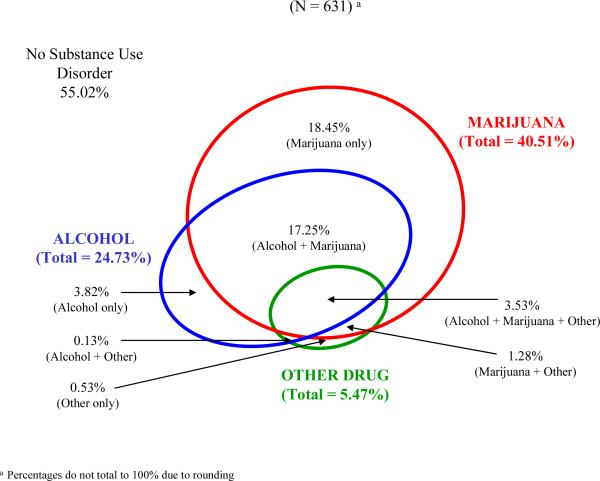

Nearly 50% of males and 45% of females had one or more SUDs; 21.35% of males and 22.19% of females had two or more SUDs. Figures 1 and 2 report the prevalence of SUDs in the past six months by sex for the entire sample. Group 2 (alcohol use disorder only) comprised 4.59% of males and 3.82% of females. Significantly more males (23.63%) than females (18.45%) were in Group 3 (marijuana use disorder only) (t = −2.16, df =4,1757, p=0.03). Group 4 (both alcohol and marijuana use disorders) comprised 19.42% of males and 17.25% of females. Significantly more females (5.47%) than males (2.44%) were in Group 5 (other illicit drug use disorders inclusive of alcohol or marijuana) (t = 2.92, df = 4,1757, p=0.01).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Single and Multiple Substance Use Disorders Among Male Detainees

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Single and Multiple Substance Use Disorders Among Female Detainees

Racial/ethnic differences

Table 1 reports types of SUDs by sex and race/ethnicity for the complete sample (N=1774). Among males, significantly more non-Hispanic white and Hispanics were in Group 5 compared to African Americans; significantly more non-Hispanic whites were in Group 5 than Hispanics.

Table 1.

Prevalence of substance use disorder categories by sex and race/ethnicitya

| Males (N=1141)b | Females (N=631) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance Use Disorderc |

African American (N=563) |

Non-Hispanic white (N=203) |

Hispanic (N=375) |

F-tests of race/ethnicityd |

Protected tests of Race/ethnicity |

African American (N=417) |

non-Hispanic white (N=86) |

Hispanic (N=128) |

F-tests of race/ethnicityd |

Protected tests of Race/ethnicity |

||||

| N | % | % | % | F value | p value | N | % | % | % | F value | p value | |||

| Group 1 | 581 | 51.41 | 37.79 | 44.77 |

Reference Groupd |

-------- | -------- | 340 | 58.55 | 38.53 | 49.82 |

Reference Groupd |

-------- | |

| Group 2 | 53 | 3.56 | 6.22 | 9.24 | 2.81 | 0.06 | 25 | 3.37 | 4.59 | 5.25 | 1.20 | 0.30 | ||

| Group 3 | 243 | 24.15 | 23.33 | 22.01 | 0.68 | 0.50 | 113 | 20.40 | 13.76 | 12.90 | 0.49 | 0.61 | ||

| Group 4 | 194 | 20.40 | 11.62 | 17.87 | 0.44 | 0.64 | 110 | 16.71 | 22.48 | 16.43 | 2.49 | 0.08 | ||

| Group 5 | 70 | 0.48 | 21.04 | 6.11 | 17.35 | 0.00 | non-Hispanic white>African American; non-Hispanic white> Hispanic; Hispanic>African American | 43 | 0.96 | 20.64 | 15.61 | 18.19 | 0.00 | non-Hispanic white>African American; Hispanic>African American |

| Totale | 1141 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 631 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.01 | ||||||

Each cell is weighted to reflect the demographic characteristics of the detention center; all categories are mutually exclusive.

2 participants of “other” race/ethnicity, both male, were excluded.

Group 1 = no disorder, Group 2 = alcohol use disorder only, Group 3 = marijuana use disorder only, Group 4 = both alcohol and marijuana use disorders, and Group 5 = other illicit drug use disorders whether or not alcohol or marijuana use disorders are also present.

Tests of race/ethnicity compare African Americans, non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics in Groups 2 through 5 to Group 1 (no disorder). All tests of race/ethnicity are within sex.

Total percents do not all sum to 100% due to rounding

Similarly, among females, significantly more non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics were in Group 5 than African Americans.

Age differences

Table 2 reports types of SUDs by sex and age for the entire sample. Among males, the youngest participants (ages 10–13) had significantly lower prevalence of all combinations of SUDs than youth 16 years and older. The youngest participants also had significantly lower prevalence of all combinations of SUDs than youth 14–15 years except for Group 2 (alcohol use disorder only). There were no significant differences in prevalence of SUDs between the two older age groups (14–15 and 16+).

Table 2.

Prevalence of substance use disorder categories by sex and agea

| Males (N=1143) | Females (N=631) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance Use Disorderb |

10–13 yrs (N=313) |

14–15 yrs (N=348) |

16+ yrs (N=482) |

F-tests of agec |

Protected tests of age |

10–13 yrs (N=55) |

14–15 yrs (N=340) |

16+ yrs (N=236) |

F-tests of agec |

Protected tests of age |

||||

| N | % | % | % | F value | p value | N | % | % | % | F value | p value | |||

| Group 1 | 583 | 72.58 | 49.67 | 45.80 |

Reference Groupc |

-------- | -------- | 340 | 69.46 | 54.98 | 51.54 |

Reference Groupc |

-------- | -------- |

| Group 2 | 53 | 2.37 | 2.68 | 6.62 | 5.56 | 0.00 | 16+>10–13 | 25 | 5.22 | 3.00 | 4.69 | 0.63 | 0.53 | |

| Group 3 | 243 | 14.59 | 24.72 | 24.43 | 10.98 | 0.00 | 16+>10–13; 14–15 >10–13 | 113 | 12.52 | 17.82 | 20.81 | 1.66 | 0.19 | |

| Group 4 | 194 | 9.63 | 20.38 | 20.48 | 12.55 | 0.00 | 16+>10–13; 14–15 >10–13 | 110 | 6.79 | 18.71 | 17.64 | 2.58 | 0.08 | |

| Group 5 | 70 | 0.84 | 2.55 | 2.66 | 8.45 | 0.00 | 16+>10–13; 14–15>10–13 | 43 | 6.01 | 5.49 | 5.31 | 0.04 | 0.96 | |

| Total d | 1143 | 100.01 | 100.00 | 99.99 | 631 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.99 | ||||||

Each cell is weighted to reflect the population of the detention center; al categories are mutually exclusive.

Group 1 = no disorder, Group 2 = alcohol use disorder only, Group 3 = marijuana use disorder only, Group 4 = both alcohol and marijuana use disorders, and Group 5 = other illicit drug use disorders whether or not alcohol or marijuana use disorders are also present.

Tests of race/ethnicity compare African Americans, non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics in Groups 2 through 5 to Group 1 (no disorder) All tests of race/ethnicity are within sex.

Total percents do not all sum to 100% due to rounding

Among females, there were no significant differences among the three age groups.

Combinations of SUDs among detainees with any SUD (N=851)

Next, we examined only those detainees who had one or more SUDs. (This analysis is available from the authors).

Among youth with any SUD, 42.66% of males and nearly half (49.43%) of females had two or more SUDs. Among youth with an alcohol use disorder, 81.84% of males and 84.56% of females also had a drug use disorder (marijuana and/or other drugs). Conversely, among detained youth with a drug use disorder (marijuana and/or other illicit drugs), 45.46% of males and 50.89% of females also had an alcohol use disorder.

Among those in Group 5 (other illicit drug use disorders inclusive of alcohol or marijuana), 79.17% of males and 90.51% of females also had either alcohol or marijuana use disorders, or both. Specifically, among detainees with an illicit drug use disorder: 1.14% of males and 2.42% of females also had alcohol use disorder; 27.64% of males and 23.41% of females also had marijuana use disorder; and 50.39% of males and 64.68% of females also had both alcohol and marijuana use disorders.

DISCUSSION

In the overall sample, nearly one quarter of detainees had multiple SUDs in the past six months. Nearly two fifths had both alcohol and marijuana use disorders, the most common combination. Marijuana use disorder, either alone or in combination with alcohol, was by far the most commonly abused substance. These findings are similar to prior studies that found high rates of multiple SUDs among delinquents (Domalanta et al., 2003; Jackson,1992; McKay et al., 1992; McManus et al., 1984; Milin et al., 1991; Neighbors et al., 1992).

Fewer than 6% of detainees had disorders involving illicit drugs other than marijuana; among these youth, over 80% also had either alcohol use disorder or marijuana use disorder, and over 50% had both. Although few in number, detained youth who use illicit drugs in addition to marijuana and alcohol are a concern. Abuse of illicit drugs in combination with marijuana and/or alcohol indicates a progression of serious and problematic use (Kandel, 1975), and places youth at great risk for continued dysfunction and delinquency (Elliot et al., 1989).

Comparing our findings to community and treatment studies is difficult because most of the larger surveys examine substance use, not disorder or multiple disorder. However multiple SUDs among detainees appear to be substantially higher than community rates (21.4% – 22.2% vs. 0.4% – 11%) (Cohen et al., 1993; Kandel et al., 1997b; Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001b).

We found some demographic differences:

Racial/ethnic differences Among both males and females, significantly more non-Hispanic whites and Hispanic detainees had combinations of SUDs involving illicit drugs other than marijuana than did African Americans. These racial/ethnic differences of multiple SUDs confirm those of prior studies of general population youth (Kandel, et al., 1997b; Kilpatrick et al., 2000).

Sex differences Significantly more females than males had disorders involving illicit drugs other than marijuana. These findings are consistent with prior studies (Abram et al., 2003; McCabe et al., 2002; Teplin et al., 2002) that found females enter the juvenile justice system with higher rates of disorder than males. Adolescent females may be also more vulnerable to becoming dependent on these illicit drugs than males (Kandel et al., 1997a), placing them at greater risk for multiple SUDs.

Age differences Our findings among males mirror patterns found in general population adolescents. Older adolescents report higher rates of disorder (Cohen et al., 1993; Kilpatrick et al., 2000). Among females, our sample size may have been too small to detect age differences.

Directions for future research

We recommend research in three areas:

Trajectories of multiple SUDs Our data revealed important sex, racial/ethnic, and age differences in patterns of multiple SUDs. These differences suggest varying trajectories for multiple SUDs among youth at risk for delinquency. Longitudinal studies of high risk youth will allow us to identify social, psychological, and environmental factors contributing to the initiation, persistence and escalation of substance use disorders, and also identify factors that lead to remission. This information is needed to help guide gender and culturally specific treatment interventions.

Treatment outcomes of detainees with multiple SUDs Several empirically-supported treatments have been developed for adolescents who abuse substances (Catalano et al., 1991; Cormack and Carr, 2000; Henggeler et al, 1992, 1999, 2002), the majority of whom use multiple substances (AACAP, 1997; Deas et al., 2000). Despite this, few studies have examined the effectiveness of treatment modalities for specific combinations of substance disorder among juveniles. Future studies can identify differences in treatment outcome among adolescents with different combinations of SUDs, establish what characteristics of treatment are most beneficial, and create model treatments that can be easily disseminated and replicated (Dennis et al., 2003).

Limitations

The DISC 2.3 does not assess the sequence of onset of SUDs. Nor could we investigate whether substance use causes delinquency, or is merely a frequent characteristic of detainees. Our data may be generalizable only to detained youth in urban detention centers with a similar demographic composition. Because we did not interview caretakers (few would have been available), the reliability of our data is limited by the veracity of our respondents' self-report (McClelland et al., in press). Underreporting of symptoms and of impairment related to use is common among adolescents (Schwab-Stone et al., 1996). Thus, our rates may understate the true prevalence of SUDs. Our findings may have been different if we had used DSM-IV criteria. Finally, the DISC 2.3 combines diagnoses for several drugs (i.e., heroin, cocaine, PCP, barbiturates, etc.) into one category, other drug. This limited our assessment of the patterns and prevalence of specific combinations of drug use.

Despite these limitations, our findings may provide important implications for mental health policy and clinical treatment.

Implications for Mental Health Policy

Ensure continuity of services in the community The average stay in detention centers is two weeks (Snyder and Sickmund, 1999); many youth then return to the same high risk environment where substance use began (Dembo et al., 1993). Most communities lack sufficient treatment programs for youth after detention (Faenza et al., 2000). In the general population, approximately half of all youth, and even more minority youth, who need services do not receive them (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Clinicians can help eliminate these disparities by working with juvenile courts and detention centers to ensure successful transitions into treatment in the community.

Target high risk youth without addictions Half of the detainees in our sample have not yet developed SUDs. While this does not indicate abstinence, prevention programs targeted towards these youth could reduce the likelihood that substance use will escalate into one or more substance use disorders. Programs must be repeated over time (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1997), and must target multiple domains of the adolescent's life (AACAP, 1997; Winters, 1999), e.g. the youth's family, peers, and school system. Developing the skills to resist drugs will reinforce personal attitudes toward abstinence, and increase social competency (NIDA, 1997; Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2000).

Clinical Implications

Among youth who abuse substances, multiple SUDs are the rule and not the exception; among detained youth with any SUD, nearly half had multiple SUDs. Treatment programs for youth should not mimic successful adult treatment programs (Crowe and Reeves, 1994). Rather, treatment programs for youth must target the specific needs of adolescents: level of cognitive development, family situation, educational needs, and many other factors (AACAP, 1997; Winters, 1999). We must:

Target all substances of abuse, especially marijuana. All major substances of abuse, including alcohol and nicotine, should be targeted for effective treatment and intervention. Further, because our findings show that marijuana abuse is so prevalent among detainees, and because it is a major gateway drug (Yamaguchi and Kandel, 1984), it requires special attention. National data indicate that adolescents are increasingly dependent on cannabis (Dennis et al., 2002), particularly in conjunction with alcohol use (OAS, 2001). Moreover, adolescents are three times more likely than adults to experience one or more symptoms associated with cannabis dependence (OAS, 2000). Clinicians need to be aware of the widespread use and significant dysfunction associated with this substance use disorder in adolescents.

Address comorbid mental disorders Compared to youth who have a single SUD, youth with multiple SUDs have higher rates of comorbid psychopathology (Milin et al., 1991; Neighbors et al., 1992) and require a continuum of services. A recent report to Congress noted that there are few effective treatments for adolescents with comorbid disorders (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002). Clinicians must be responsive to the needs of youth with comorbidity, treating psychiatric and substance use disorders simultaneously.

The Surgeon General has called for effective community outreach and culturally sensitive treatment plans to reduce barriers to mental health services among underserved and minority populations (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). By increasing enrollment and retention of delinquent youth in appropriate substance abuse treatment, community programs could reduce criminal recidivism (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1998) and reduce the substantial long-term cost of substance abuse and criminal activity to our nation's youth and to society (Cohen, 1998).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Ann Hohmann, Ph.D., Kimberly Hoagwood, Ph.D., and Heather Ringeisen, Ph.D., for invaluable advice. We also thank Jacques Normand, Ph.D., Helen Cesari, M.S., Richard Needle, Ph.D., Grayson Norquist, M.D., Delores Parron, Ph.D., Celia Fisher, Ph.D, Mark Reinecke, Ph.D., and our reviewers for their thoughtful comments.

We thank all project staff, especially Amy Lansing, Ph.D., for supervising the data collection, Amy Mericle, Ph.D., for preparing the data, and Laura Coats, editor and research assistant. We also greatly appreciate the cooperation of everyone working in the Cook County systems, especially David Lux, our project liaison. Without Cook County's cooperation, this study would not have been possible. Finally, we thank the participants for their time and willingness to participate.

FUNDING This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH54197 and R01MH59463 (Division of Services & Intervention Research and Center for Mental Health Research on AIDS), and grant 1999-JE-FX-1001 from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Major funding was also provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Center for Mental Health Services, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (National Center on Injury Prevention & Control and National Center for HIV, STD & TB Prevention), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health, the NIH Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the NIH Office on Rare Diseases, The William T. Grant Foundation, and The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Additional funds were provided by The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Open Society Institute and The Chicago Community Trust. We thank all our agencies for their collaborative spirit and steadfast support.

References

- Aarons GA, Brown SA, Hough RL, Garland AF, Wood PA. Prevalence of Adolescent Substance Use Disorders Across Five Sectors of Care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:419–426. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abram KM, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders in Youth in Juvenile Detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1097–1108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Almog YJ, Anglin MD, Fisher DG. Alcohol and heroin use patterns of narcotics addicts: gender and ethnic differences. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1993;19:219–238. doi: 10.3109/00952999309002682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Practice Parameters for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Substance Use Disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;10(Supplement):140S–156S. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199710001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashfield RK, Aldenderfer MS. The methods and problems of cluster analysis. In: Nesselroad JR, Cattel RB, editors. Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology. 2nd Edition Plenum Press; New York: 1988. pp. 447–473. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo M, Woodbury-Farina M, Canino GJ, Rubio-Stipec M. The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in Puerto Rico. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1993;17:329–344. doi: 10.1007/BF01380008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano R, Hawkins J, Wells E, Miller J. Evaluation of the effectiveness of adolescent drug abuse treatment, assessment of risks for relapse and promising approaches for relapse prevention. Int J Addict. 1991;25:1085–1140. doi: 10.3109/10826089109081039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Drug and Alcohol Abuse Implications for Treatment. NIDA Treatment Research Monograph No. 125. US Dept. on Health and Human Services, NIDA; Washington, DC: 1981. The Effects of Combined Alcohol/Drug Abuse on Human Behavior; pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd edition Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, New Jersey: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J, Kasen S, Velez CN, Brook J, Streuning EL. An Epidemiological Study of Disorders in Late Childhood and Adolescence - I. Age- and Gender-Specific Prevalence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1993;34:851–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA. The Monetary Value of Saving a High-Risk Youth. Journal of Qualitative Criminology. 1998;14:5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cormack C, Carr A. Drug abuse. In: Carr A, editor. What works with children and adolescents? A critical review of psychological interventions with children, adolescents and their families. Routledge; London: 2000. pp. 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe H, Reeves R. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 94-2075. Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration; 1994. Technical Assistance Publication Series 11: Treatment for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse: Opportunities for Coordination. Available at http://www.treatment.org/Taps/Tap11/tap11foreword.html. Accessed 11-18-03. [Google Scholar]

- Deas D, Riggs P, Klangenbucher J, Goldman M, Brown S. Adolescents are not adults: Developmental considerations in alcohol users. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:232–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Dertke M, Borders S, Washburn M, Schmeidler J. The Relationship Between Physical and Sexual Abuse and Tobacco, Alcohol, and Illicit Drug Use Among Youths in a Juvenile Detention Center. Int J Addict. 1988;23:351–378. doi: 10.3109/10826088809039203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Williams L, Schmeidler J. Addressing the problems of substance abuse in juvenile corrections. In: Inciardi J, editor. Drug Treatment and Criminal Justice Criminal Justice System Annuals. Vol 27. Sage Publications; Newbury Park: 1993. pp. 97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Barbour TF, Roebuck C, Donaldson J. Changing the focus: the case for recognizing and treating cannabis use disorders. Addict. 2002;97(Suppl 1):4–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Dauwud-Noursi S, Muck RD, McDermeit M. The need for developing and evaluating adolescent treatment models. In: Stevens SJ, Morral AR, editors. Adolescent substance abuse treatment in the United States: Exemplary Models from a National Evaluation Study. Haworth Press; Binghamton, NY: 2003. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Domalanta DD, Risser WL, Roberts RE, Risser JMH. Prevalence of depression and other psychiatric disorders among incarcerated youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:477–484. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046819.95464.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Huizinga D, Menard S. Multiple Problem Youth: Delinquency, Substance Use, and Mental Health Problems. Springer-Verlag New York Inc; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Faenza M, Siegfried C, Wood J. Community Perspectives on the Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment Needs of Youth Involved in the Juvenile Justice System. National Mental Health Association and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Alexandria, VA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB. Integrating science and ethics in research with high-risk children and youth. Soc Res Child Dev. 1993;7:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JT. Psychosocial factors related to substance abuse among delinquent females: implications for prevention and treatment. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1982;52:261–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb02687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilvarry E. Substance use in young people. Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:55–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler S, Melton G, Smith L. Family preservation using multisystemic therapy: An effective alternative to incarcerating serious juvenile offenders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:953–961. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, Brondino MJ. Multisystemic Treatment of Substance Abusing and Dependent Delinquents: Outcomes, Treatment Fidelity, and Transportability. Ment Health Serv Res. 1999;1:171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022373813261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Clingempeel WG, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Four year Follow-Up of Multisystemic Therapy with Substance Abusing and Dependent Juvenile Offenders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(7):868–874. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL. Treating combined alcohol and drug abuse in community-based programs. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Vol 8. Plenum Press; New York: 1990. pp. 273–283. (Combined alcohol and other drug dependence) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MS. Drug use patterns among Black male juvenile delinquents. J Alcohol Drug Education. 1992;37:64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Stages of adolescent involvement in drug use. Science. 1975;190:912–914. doi: 10.1126/science.1188374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Chen K, Warner LA, Kessler RC, Grant B. Prevalence and demographic correlates of symptoms of last year dependence on alcohol, nicotine, marijuana and cocaine in the US population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997a;44:11–29. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Johnson JG, Bird HR, Canino G, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Regier DA, Schwab-Stone M. Psychiatric Disorders Associated with Substance Use Among Children and Adolescents: findings from the Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) Study. J Ab Child Psychol. 1997b;25:121–132. doi: 10.1023/a:1025779412167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: data from a national sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Arria AM, Mezzich AC, Bukstein OG. Patterns of polydrug use in adolescent alcohol abusers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1993;19:511–521. doi: 10.3109/00952999309001639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KM, Lansing AE, Garland A, Hough R. Gender differences in psychopathology, functional impairment, and familial risk factors among adjudicated delinquents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:860–867. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Murphy RT, McGuire J, Rivinus TR. Incarcerated adolescents' attributions for drug and alcohol use. Addict Behav. 1992;17:227–235. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90028-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus M, Alessi NE, Grapentine WL, Brickman A. Psychiatric Disturbance in Serious Delinquents. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1984;23:602–615. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GM, Teplin LA, Abram KA. Detection of Substance Use and Abuse Among Youth in Detention: Findings from the Northwestern Juvenile Project. OJJDP Bulletin. (In Press) [Google Scholar]

- Milin R, Halikas JA, Meller JE, Mores C. Psychopathology among substance abusing juvenile offenders. Am Academy Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:569–574. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors B, Kempton T, Forehand R. Co-occurrence of substance abuse with conduct, anxiety, and depression disorders in juvenile delinquents. Addict Behav. 1992;17:379–386. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90043-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse . Preventing drug use among children and adolescents: A research based guide for parents, educators, and community leaders. 1997. NIH Publication No. 04-4212(A) [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies . Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 1994–1999: National admissions to substance abuse treatment services. (DHHS Publication No. SMA 01–3550, Drug and Alcohol Services Information System Series S-14. Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2001. Available at http://www.samhsa.gov/oas/dasis.htm#teds2). Accessed 11-18-03. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies . National Household Survey of Drug Abuse: Main Findings 1998. Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2000. Available at http://www.samhsa.gov/statistics. Accessed 11-18-03. [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Control Policy Evidence-Based Principles for Substance Abuse Prevention. 2000 Available at http://www.ccapt.org/evidence2000.pdf. Accessed 11-18-03.

- Otto RK, Greenstein JJ, Johnson MK, Friedman RM. Prevalence of Mental Disease Among Youth in the Juvenile Justice System. In: Cocozza JJ, editor. Responding to the Mental Health Needs of Youth in the Juvenile Justice System. National Coalition for the Mentally Ill in the Criminal Justice system; Seattle, WA: 1992. pp. 7–48. [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Shaffer D, Fisher P, Schawb-Stone ME, Davies M, Gioia P. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Revise Version (DISC-R): III. concurrent criterion validity. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:658–665. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Dolinsky ZS, Babor TF, Meyer RE. Psychopathology as a predictor of treatment outcome in alcoholics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:505–513. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan-Szal GA, Chatham LR, Simpson DD. Importance of Identifying Cocaine and Alcohol Dependent Methadone Clients. Am J Addict. 2000;9:38–50. doi: 10.1080/10550490050172218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab-Stone M, Shaffer D, Dulcan M, Jensen PS, Fisher CB, Bird HR, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Lichtman JH, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Rae DS. Criterion validity of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3) Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:878–888. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan M, Davies M, Piacentini J, Schawb-Stone ME, Lahey BB, Jensen PS, Bird HR, Canino G, Regier DA. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA Study. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:865–877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickmund M, Wan Y. Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement Databook. Available at: http://www.ojjdp.ncjrs.org/ojstatbb/cjrp. Accessed 03-26-02.

- Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods. Iowa State University Press; Ames, Iowa: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Synder HN, Sickmund M. Juvenile Offenders and Victims: 1999 National Report. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Report to Congress on the prevention and treatment of co-occurring substance abuse disorders and mental disorders. US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration . The DASIS Report: Polydrug Use Among Treatment Admissions 1998. US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Volume II Technical Appendices and Selected Data Tables. Rockville, MD: 2001b. (NHSDA Series H-18, DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3759) [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Services Research Outcomes Study: September 1998. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 1998. Available at http://www.samhsa.gov/oas/Sros/httoc.htm. Accessed 11-18-03. [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, Mericle AA. Psychiatric Disorders in Youth in Juvenile Detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1133–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Gil AG. Psychiatric and substance use disorders in South Florida: racial/ethnic and gender contrasts in a young adult cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:43–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services . Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; Rockville, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services . Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity -- A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; Rockville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Warner LA, Hughes M, Anthony JC, Nelson CB. Prevalence and Correlates of Drug Use and Dependence in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:219–229. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950150051010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC. Treating adolescents with substance use disorders: an overview of practice issues and treatment outcomes. Subst Abus. 1999;20:203–225. doi: 10.1080/08897079909511407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Kandel DB. Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood, III: predictors of progression. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:673–681. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.7.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]