Abstract

Purpose

To pilot a stepped collaborative care intervention for postpartum depression (PPD) and evaluate health differences between self-diagnosed depressed and non-depressed women.

Methods

Participants – 506 mothers of infants from 7 clinics – completed surveys at 0–1, 2, 4, 6, and 9 months postpartum and a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). SCID-positive depressed women were randomized to stepped collaborative care or usual care. Nine-month treatment, health, and work outcomes were evaluated for stepped care vs. control depressed women (n = 19, 20), and self-diagnosed depressed vs. non-depressed women (n = 122, 344).

Results

Forty-five women had SCID-positive depression, while 122 had self-diagnosed depression. For SCID-positive depressed women, the stepped care intervention increased mothers’ awareness of their depression diagnosis (100% vs. 61%, p = .008) and their receipt of treatment (94% vs. 56%, p = .019). Self-diagnosed depressed women (vs. non-depressed) had more depressive symptoms and acute care visits, worse general and mental health, and greater impact of health problems on regular activities.

Conclusions

The stepped care intervention improved women’s knowledge of their PPD diagnosis and their receipt of treatment. However, our formal diagnostic procedures missed many women whose depressed mood interfered with their health and function.

Keywords: postpartum depression, treatment outcome, mental health services

Postpartum depression (PPD), the most prevalent serious complication of pregnancy, affects up to 22% of women who have recently given birth.1 Given that fewer than half of postpartum women are screened for depression,2–5 it follows that only a minority of cases are likely treated.

In studies of non-postpartum depression, collaborative treatment of depression has been acclaimed as superior to traditional treatment methods (e.g., antidepressants and/or psychotherapy). Collaborative care consists of a team-based approach to care that, when applied to mental disorders, involves a primary care provider, mental health specialist (psychiatrist and/or psychologist or social worker), care manager, 6–11 and other allied health professionals as needed. The team usually offers enhanced provider/patient education on major depression, treatment with antidepressant medication and/or psychotherapy, and regular care manager monitoring (often by telephone) of depressed patients’ symptoms and treatment adherence.7 A recent meta-analysis of 37 collaborative care studies documents that collaborative care, compared to usual depression care, improves depression treatment adherence and outcomes, with long-term benefits of at least 5 years.12

Collaborative care treatment programs can improve not only depressive symptoms,6,7,10,13,14 but also depressed patients’ function,7,14,15 quality of life,7 pain,14 work performance and productivity,16,17 marital adjustment,18 and physical health, including chronic health conditions such as arthritis.14

A special type of collaborative care, stepped care treatment, delivers care in a step-wise manner, beginning with screening, diagnosis, and initial treatment in a primary care setting, and adding care manager follow-up and support, decision support, and mental health consultation or referral as needed for patients with persistent depressive symptoms.19 Although it would seem that collaborative care would also improve PPD outcomes, neither collaborative or stepped care have ever been experimentally tested in a postpartum population. Such evaluation would be important, given that postpartum women often possess unique barriers to treatment, such as need for childcare during mental health visits,20 concerns about medication effects on nursing infants,21 and fear of judgment or referral to child protection.22

The purpose of this study was to pilot a stepped collaborative care treatment program for women with postpartum depression, to begin to test the impact of such a program on women’s mental and physical health outcomes, and to evaluate differences in health outcomes between women with and without postpartum depression.

Methods

General Procedures

Prior to its initiation, the study was approved by the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board. Subjects were recruited for the study from October 1, 2005, through September 30, 2006, during well-child visits, and surveys were administered from October, 2005 through June, 2007. Mothers registering their infants for an initial (0–1 month) well-child visit at one of 7 participating clinics were given an enrollment packet by the receptionist. The packet consisted of a brief description of the study, enrollment form (indicating their willingness to participate), consent form, and initial survey. Enrollees were given follow-up surveys at subsequent 2, 4, and 6 month well-child visits (or alternatively completed telephone or mailed surveys), and were mailed a final survey at 9 months postpartum. Mothers were also asked to complete the depression module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)23 within 2 weeks of the 0–1 month survey, and subsequently if a previously non-depressed woman developed either a positive 2-question depression screen or 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) at a later interval.

Study Participants and Practices

Participants were recruited from 7 Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area clinics: four were urban university-affiliated family medicine residency clinics and three were suburban, private pediatric clinics (staffed by approximately 130 and 11 physicians respectively). Inclusion criteria were: mother of a 0–1 month old infant who was registered at one of the participating clinics, English literate, and 12 years of age and older.

Provider Training

Providers from the participating practices were offered a one hour training session and printed educational materials on PPD and study procedures prior to the study’s initiation. The training session covered the following topics: PPD background, risk factors, diagnosis, study protocol and methods, scoring of two depression screens (2-question screen and PHQ-9), and management, including components of stepped collaborative care, role of primary care provider, use of antidepressants and psychotherapy, selection of antidepressants for breastfeeding mothers, antidepressant side effects, duration of treatment, importance of social support, and indications for mental health referral.

Measures

Survey measures included: 1) demographic information (initial survey): mother’s age, education, race/ethnicity, total family income, health insurance, marital status, number of children, and delivery date; 2) depression screening measures (all surveys): 2-question screen (asks about problems with mood or pleasure over past month; positive if either question is answered “yes”) and PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire, 9-item depression module; positive if score >10);5 3) receipt of treatment (9-month survey): mothers’ self-report of being depressed or receiving a depression diagnosis after delivery, mother’s report of treatment in general, and of antidepressant treatment and/or counseling in particular; 4) duration of treatment (9-month survey): number of weeks treated, treatment for ≥12 weeks, and number of counseling and psychiatry visits; 5) health outcomes (0-1 and 9-month surveys): PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire, 9-item depression module),5 mental health scale (5 items, from SF-36),24 general health (single item from SF-36), number of mother’s and infant’s days ill over 2 weeks, number of mother’s and infant’s acute care visits to clinic/urgent care/emergency room over 2 weeks; 6) work outcomes (9-month survey): length of maternity leave, number of hours missed at work over past 7 days, number of hours worked over past 7 days, and impact of health problems on non-job-related activities (work-related questions taken from the Work Productivity and Impairment Questionnaire);25 and 7) satisfaction with depression treatment (9-month survey).

Depression Diagnosis

All participants were expected to complete the depression module of the SCID interview (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV)23 by telephone within two weeks of completing their 0–1 month survey, and again later if a previously non-depressed woman was screen-positive on a follow-up survey. The SCID interview, our reference standard for the diagnosis of major depressive disorder, was conducted by three trained psychology doctoral students whose training consisted of observing SCID training tapes and completing five practice tapes under the supervision of an experienced doctoral level clinical psychologist, followed by weekly quality assurance assessment conferences throughout the study. Sixty-eight (13.4%) of the women could not be reached for the initial SCID, and an additional 9 women could not be reached for a follow-up SCID interview.

SCID-positive depressed participants were informed of the depression diagnosis, and these women were advised to see their primary care provider within one week. Providers were informed about their patients’ depression diagnoses, the nature of the study, and their patients’ participation in it. While 31 of the randomized patients were each seen by a different provider, the remaining 8 patients shared providers: 3 providers had one patient in each of the two treatment groups, and one provider had two patients in the control group.

Participants were also given the opportunity to self diagnose depression by a 9-month survey question: “Since your baby was born, have you been depressed, or diagnosed with depression?” (yes/no).

Randomization

Women who became SCID-positive at 0-6 months postpartum were randomized to stepped or usual care, using computer-generated block randomization schedules (block size of 10), which were stratified by clinic. This was done in order to ensure an approximately equal split of subjects in each clinic. Providers were not blinded to their patients’ group assignment.

Intervention

The Stepped Care intervention included the following: 1) referral to the primary care provider for initial treatment (we recommended an antidepressant and/or psychotherapy referral, both found to be effective in previous research21); 2) regular care manager telephone follow up (see details below); 3) decision support for primary care providers (e.g., advice regarding specific antidepressants, additional treatment, or mental health referral); 4) consultation or referral to a mental health specialist for complex cases (e.g., psychiatrists conducted psychiatric evaluations and adjusted medications; therapists provided psychotherapy, using cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, or other therapies depending on the needs of the patient); and 5) patient education provided through the primary physician, care manager, and a mailed Postpartum Depression brochure. Stepped Care treatment was continued until either the patient was in remission, using Dietrich et al.’s (2003) definition of remission as a PHQ-9 score of < 5,8 or the patient had passed the 9-month follow-up period. After this point, depression care continued according to the provider’s standard.

The care manager was a registered nurse with mental health experience. She was trained in telephone call procedures by the P.I., and training included: PHQ-9 administration, depression diagnosis and treatment, patient education and social support, use of the telephone protocol form, and triage of women with suicidal ideation.

Stepped care women received an average of 4.1 care manager calls. These calls, which usually lasted 20–30 minutes, were attempted every two weeks until symptom remission and addressed the following: depressive symptoms (using PHQ-9), mental health visits, treatment adherence and side effects, social support, suicidal ideation/plans, and lifestyle issues including nutrition, exercise, and rest. The content of each call was documented on a form, and a copy was faxed to the woman’s provider. If a participant’s symptoms were not resolving as expected, this was specifically communicated.

If a call or survey revealed suicidal ideation (for any participant), the P.I. was informed, and the P.I. contacted the participant to determine the severity of her symptoms. For cases where there was potential risk for injury or suicide (5 stepped care women, 1 control woman, and 1 SCID-negative woman), a plan of action was developed and executed that included: informing the woman’s provider and recommending an urgent visit to the primary care and/or mental health provider or emergency room. Also, if warranted and if the mother agreed, the P.I. communicated with the mother’s adult friend or relative to request 24-hour supervision of the mother until she was determined to be safe by a health professional. Providers were responsive to our communication about urgent problems, and worked with the P.I. in developing and implementing a plan of action.

Control group women were also informed of their depression diagnosis and referred to their primary care provider, who managed the depression according to the provider’s usual practice.

Statistical Analysis

In order to control for experiment-wide error rate on multiple dependent variables, four separate multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were performed to assess the impact of treatment on receipt of treatment, duration of treatment, health outcomes, and work outcomes (see “Measures” for a listing of variables included within each of these four categories). Independent variables were treatment group and specialty (family medicine vs. pediatric clinic). If a given MANOVA was significant, individual ANOVAs, looking at dependent variables within the group, were examined.

To determine the impact of the intervention on specific 9-month health, work, and duration of treatment outcomes, we performed one-way analyses of variance (or chi-square tests) on randomized women, with treatment group as the independent variable, and the following as dependent variables: PHQ-9, mental health, general health, mother’s and infant’s days ill and acute care visits, length of maternity leave, hours spent at work over past week, hours of missed work over past week, impact of health problems on work productivity and on regular (non-job related) activities, duration of treatment, treatment duration of >12 weeks, and number of counseling and psychiatry visits.

A post-hoc analysis was performed to compare 9-month health outcomes between women with self-diagnosed depression (both treated and untreated) vs. no depression. To compare these 3 groups while controlling the experiment-wise error rate, we initially performed a MANCOVA, with the three “as-treated” groups and specialty as independent variables, the baseline (0–1 month) measure of the dependent variable as the covariate, and the following as dependent variables: PHQ-9, mental health, general health, mother’s and infant’s days ill, mother’s and infant’s health care visits, and non-job activities. Given that the MANCOVA result was significant, we then performed univariate ANCOVAs on the above-listed dependent variables. Group comparisons on job-related outcomes could not be effectively evaluated, due to the small number of depressed women who were at work at 9 months. A descriptive analysis was performed to identify reasons that self-diagnosed depressed women did not receive treatment.

T-tests and chi-square tests were used to compare stepped care and control subjects on baseline demographic and health characteristics, and to compare drop-outs (women who did not complete the final survey) to study completers on selected variables.

Results

Participants’ Characteristics

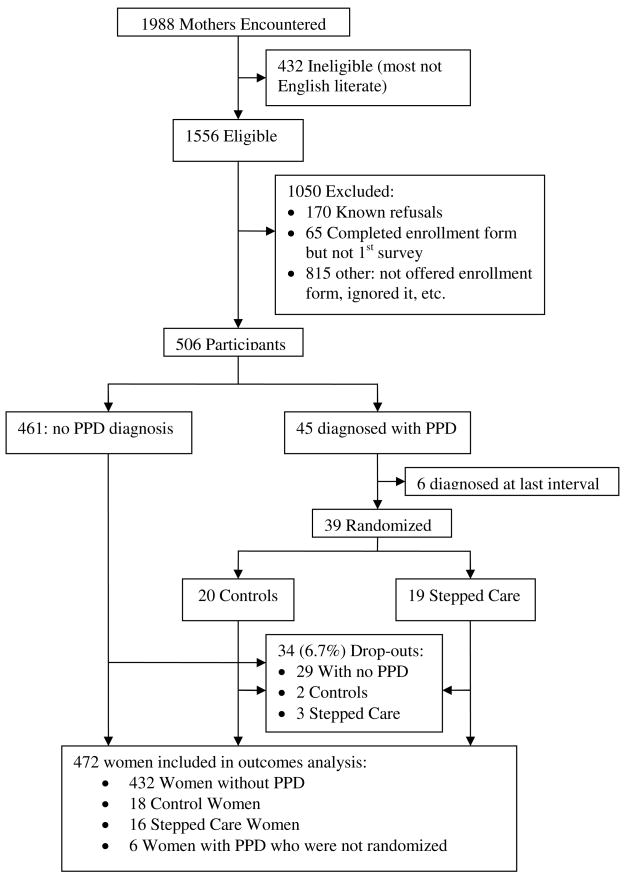

A total of 506 women participated in the study, which represented approximately 33% of the estimated 1556 eligible (English literate) women. Figure 1 illustrates the progress of subjects through the phases of the study.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Participants’ Progress through Phases of the Study

Participants’ characteristics were as follows

67% were white, 18% black, and 7% Asian; 27% had annual family incomes of less than $20,000 while 37% had incomes of $80,000 or greater; 16% had less than a high school diploma, and 52% had a 4 year degree or more; 55% had private health insurance while 31% had medical assistance. Mothers’ mean age was 29.1 years (sd = 6.2; range: 16-46); 65% of mothers were married, 64% were employed, and 42% had only one child. One hundred sixty-seven (33%) participants were recruited from family medicine clinics, and 339 (67%) from pediatric clinics. More detail on demographic characteristics is provided in a prior publication.26

Only 34 (6.7%) of the 506 participants did not complete the final survey, and were therefore considered drop-outs. When drop-outs were compared to those who completed the study, dropouts were found to be younger (26 vs. 29 years old); less educated (32% vs. 73% had post-high school education); less likely to be married (27% vs. 68%); and had more children (2.5 vs. 1.9), lower family incomes (64% vs. 25% had annual income <$20,000), and more depressive symptoms (21% vs. 6% had a positive PHQ-9).26

SCID-Positive Depression

Forty-five women (8.9%) had SCID-positive depression: 19 were randomized to stepped care (intervention group), and 20 to usual care (control group); 6 women were diagnosed at the 9-month interval, and therefore could not be randomized. Thirty-four of the 39 randomized women completed the final survey. Baseline demographic and health characteristics of this group indicate that a majority had low education and income levels, and most were non-white and on medical assistance. No significant baseline differences were seen between the two treatment groups, indicating that the randomization procedure was effective (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Comparisons between Stepped Care and Control Subjects on Demographic and Health Characteristics

| Characteristic | Stepped Care (n = 19) | Control (n = 20) | P Value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years: mean (sd) | 27.2 (5.2) | 28.0 (7.3) | .717 |

| Education: # (%) with ≤ high school diploma | 10 (52.6%) | 12 (60.0%) | .843 |

| Race: # (%) non-Caucasian | 11 (57.9%) | 13 (65.0%) | .748 |

| Total family income: # (%) < $40,000 | 16 (84.2%) | 13 (65.0%) | .278 |

| Insurance: % on Medical Assistance | 15 (83.3%) | 9 (52.9%) | .075 |

| Married: # (%) | 5 (26.3%) | 8 (40.0%) | .501 |

| # Children: mean (sd) | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.1) | .204 |

| PHQ-9: mean (sd) | 10.5 (8.5) | 11.7 (7.2) | .652 |

| Mental Health: mean (sd) | 18.1 (6.3) | 18.0 (5.8) | .978 |

| General Health: mean (sd) | 2.9 (0.9) | 3.2 (0.8) | .253 |

| # Illness days – mother: mean (sd) | 1.9 (4.2) | 2.5 (4.8) | .728 |

| # Illness days – infant: mean (sd) | 0.7 (3.2) | 0.4 (1.6) | .639 |

| # Acute care visits – mother: mean (sd) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.6 (2.0) | .631 |

| # Acute care visits – infant: mean (sd) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | .331 |

Determined by Chi-Square and T-Tests. Percentages are expressed as the percent of the given treatment group.

PHQ-9 score range = 0–27, with higher numbers representing more depressive symptoms.

Mental Health score range = 5–30, with higher numbers representing better mental health.

General health, single item: 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent.

Both stepped care and control women were generally satisfied with their treatment: mean (sd) = 4.4 (1.6) for stepped care group, 5.5 (1.2) for control group (p = .091; satisfaction scale: 1 = very dissatisfied, 4 = somewhat satisfied, and 7 = very satisfied). Stepped care women were receptive to care manager follow-up calls, and they each received an average of 4.1 calls (range = 0-11). Only one stepped care participant could not be reached for follow-up calls.

Impact of Intervention on Outcomes

MANOVA results (with treatment group and specialty as independent variables) showed that the stepped care intervention had a significant positive impact on receipt of treatment (λ = .738, F = 3.305, p = .035). Results from one-way ANOVAs on these individual outcomes are shown on Table 2, and indicate that the intervention improved mothers’ awareness of their depression diagnosis and their receipt of treatment, particularly antidepressant medication. For the remaining three MANOVAs (duration of treatment, health outcomes, and work outcomes), treatment group effects were non-significant. Group comparisons on specific health, work, and treatment duration outcomes are given on Table 3; there were no significant group differences, with one exception (length of leave).

Table 2.

The Impact of Stepped Care on SCID-Positive Depressed Subjects’ Self-Report of Depression and Receipt of Treatment

| Outcome | Stepped Care (n = 16) | Control (n = 18) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| # (%) Who self-reported depression after delivery | 16 (100%) | 11 (61.1%) | .008 |

| # (%) Who received treatment (antidepressants, psychotherapy) | 15 (93.8%) | 10 (55.6%) | .019 |

| # (%) Who received antidepressants | 15 (93.8%) | 10 (55.6%) | .019 |

| # (%) Who received counseling | 7 (43.8%) | 5 (27.8%) | 1.00 |

Determined by one-way analysis of variance

Table 3.

Impact of Stepped Care Treatment for PPD on 9-Month Health, Work, and Duration of Treatment Outcomes

| Outcomes | Stepped Care(n = 16) | Control (n = 18) | P Value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9: mean (sd)2 | 9.0 (7.3) | 7.6 (6.5) | .597 |

| Women with positive PHQ-9 (score ≥10): # (%) | 7 (44%) | 5 (28%) | .475 |

| Mental Health: mean (sd)3 | 18.8 (5.9) | 20.7 (5.4) | .356 |

| General Health: mean (sd)4 | 2.8 (1.0) | 2.8 (0.6) | .851 |

| # Mom’s days ill (over 2 weeks): mean (sd) | 3.3 (4.9) | 2.6 (5.0) | .869 |

| # Baby’s days ill (over 2 weeks): mean (sd) | 1.1 (3.5) | 1.9 (3.0) | .466 |

| # Mom’s clinic/urgent care visits (2 weeks): mean (sd) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.2 (.04) | .972 |

| # Baby’s clinic/urgent care visits (2 weeks): mean (sd) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.6 (1.9) | .407 |

| Length of Maternity Leave (weeks): mean (sd)5 | 23.0 (12.7) | 9.1 (4.8) | .024 |

| #Hours spent at work over past week: mean (sd) | 34.0 (2.8) | 35.0 (7.2) | .861 |

| #Hours of missed work over past week: mean (sd) | 4.0 (5.7) | 1.5 (2.1) | .296 |

| Impact of health problems on work productivity: mean (sd)6 | 1.0 (1.4) | 2.0 (2.4) | .604 |

| Impact of problems on regular (non-job) activities: mean(sd)6 | 3.9 (3.1) | 2.4 (2.8) | .562 |

| # Weeks of treatment: mean (sd) | 19.8 (11.5) | 19.6 (12.8) | .363 |

| Women treated for ≥ 12 weeks: # (%) | 9 (75%) | 4 (67%) | .252 |

| # Counseling visits: mean (sd) | 5.3 (8.8) | 2.3 (3.1) | .131 |

| # Psychiatry visits: mean (sd) | 0.8 (2.1) | 0.5 (0.8) | .928 |

Determined by one-way analysis of variance or chi-square.

PHQ-9 score range = 0–27, with higher numbers representing more depressive symptoms.

Mental Health score range = 5–30, with higher numbers representing better mental health.

General health, single item: 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent.

The analysis on length of leave included only 2 stepped care subjects and 8 control subjects.

Impact of health problems on work productivity or regular (non-job related) activities: scale of 0–10, where higher numbers represent greater negative health impact.

Specialty effects approached statistical significance in two MANOVAs: receipt of treatment (λ = .771, F = 2.769, p = .060), and health outcomes (λ = .594, F = 2.346, p = .056). In both cases, mothers whose infants attended pediatric clinics had better outcomes than those who attended family medicine clinics. There were no significant group by specialty interactions.

Self-Diagnosed Depression

When subjects were asked if they had been depressed or diagnosed with depression since delivery, 122 (24.1%) answered “yes,” with 76 (62%) reporting treatment and 46 (38%) no treatment. Three-fourths of women (344) said they had not been depressed.

MANCOVA results showed that these three self-diagnosis groups were significantly different in their health outcomes (λ = .726, F = 11.139, p = .000). Follow-up ANCOVAs found that depressed women (both treated and untreated), compared to non-depressed, had more depressive symptoms (PHQ-9), worse general health and mental health, and greater impact of health problems on regular activities. Treated depressed women, vs. the other two groups, had more acute care visits (Table 4). Specialty effects and specialty/group interactions were also significant (λ = .929, .891; F = 4.9, 3.8; p = .000, .000, respectively), with mothers from family medicine clinics, particularly those with treated self-diagnosed depression, having worse outcomes.

Table 4.

Significant Differences in 9-Month Health Outcomes between Three Self-Report Groups – Treated Depressed Women, Untreated Depressed Women, and Non-Depressed Women

| Health Outcomes: Results given as mean (sd) | Depressed/Treated (n = 76) | Depressed/Untreated(n = 46) | Non- Depressed (n = 344) | F | P Value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-92 | 7.9 (6.2) | 7.3 (5.1) | 2.3 (2.8) | 53.7 | .000 |

| Mental Health3 | 20.6 (4.9) | 21.3 (4.2) | 25.6 (2.9) | 68.8 | .000 |

| General Health4 | 3.0 (0.9) | 3.3 (0.7) | 3.8 (0.9) | 129.6 | .000 |

| # Days ill (2 weeks) – Mother | 3.3 (6.0) | 2.3 (4.4) | 1.3 (3.1) | 3.7 | .054 |

| # Days ill (2 weeks) – Baby | 1.5 (3.1) | 1.6 (3.2) | 1.1 (2.6) | 0.1 | .820 |

| # Acute care visits (2 weeks) – Mom: | 0.3 (1.5) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.5) | 35.1 | .000 |

| # Acute care visits (2 weeks) – Baby | 0.4 (1.8) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.5 | .499 |

| Impact of problems on regular activities5 | 3.2 (2.9) | 2.0 (2.5) | 1.0 (1.8) | 14.7 | .000 |

Determined by ANCOVAs.

PHQ-9 score range = 0–27, with higher numbers representing more depressive symptoms.

Mental Health score range = 5–30, with higher numbers representing better mental health.

General health, single item: 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent.

Impact of health problems on regular (non-job related) activities, scale of 0–10, where higher numbers represent greater negative health impact.

Women’s reasons for not taking depression treatment are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mothers’ Reasons for Not Taking Depression Treatment (n = 46 self-diagnosed women)

| Reason | # Mothers (%)* |

|---|---|

| Mother thought she could handle it herself | 21 (46%) |

| No time for depression visits | 16 (35%) |

| Treatment not recommended | 11 (24%) |

| Concerned about what others would think, embarrassed | 10 (22%) |

| Concerned about medication effects on nursing infant | 8 (17%) |

| Concerned about medication side effects on mother | 6 (13%) |

| Thought it was “just a phase,” a short-term problem | 5 (11%) |

| No childcare available for depression visits | 4 (9%) |

| Concerns about insurance, cost of coverage | 4 (9%) |

| Concerned about becoming dependent on medications | 3 (7%) |

| Husband/partner unsupportive of getting help | 1 (2%) |

| Worried that baby would be taken away | 1 (2%) |

Results given as number and % of women who reported that they had been depressed but not treated

Discussion

Our stepped care intervention improved mothers’ awareness of their depression diagnosis and their likelihood of being treated – both important clinical outcomes. The stepped care intervention did not, however, appear to significantly impact treatment duration, health, or work outcomes. One explanation for the absence of observed impact on these outcomes is the relatively small number of women available for these analyses: 18 for duration of treatment, 34 for health outcomes, and 10 for work outcomes. Other factors that may have contributed to non-significant group differences are the relatively brief period of follow-up and the inclusion of women with chronic depression and other associated severe mental health conditions (e.g., bipolar disease), who may have been less responsive to this treatment program. In addition, the larger number of presumably higher-risk medical assistance patients in the stepped care group (15 vs. 9, p = .075) may have blunted intervention effects.

It is interesting that women’s self reported diagnosis of depression produced nearly three times the number of depressed cases as the SCID-based diagnoses (122 vs. 45). This large discrepancy between self- and SCID-based diagnoses is likely due at least in part to the nature of our measures. For example, the SCID is designed to diagnose major depression, while the self-report question may have also identified women with transient or sub-threshold depressive symptoms. We may have also missed cases due non-completion of a survey or SCID interview, or discordance in survey timing with depressive symptoms. We are not aware of other studies comparing mothers’ self-reported depression to criterion-based depression, and in fact the term “self-reported depression” in other postpartum depression studies usually refers to positive depression surveys.27–30 This unexpected finding should be pursued in future studies.

As anticipated, our analysis comparing women from the three self-report groups – depressed/treated, depressed/untreated, and non-depressed – revealed that depressed mothers have worse mental and physical health outcomes, and depressed women’s health problems have a significantly greater impact on their non-job-related activities. Since caring for one’s infant is usually a large component of a mother’s “regular” activities, it follows that depression likely impacts a mother’s care of her newborn. Prior research has also shown a relationship between mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms.31–33 Therefore, it is important that depressed women be effectively treated, both for their own sake, and the sake of other family members.

Importantly, 46 (38%) of the self-diagnosed depressed women said they had not received treatment. While the most common reason for not receiving treatment was that women thought they could handle their depression themselves, postpartum-specific concerns were also raised, including medication effects on nursing infants, lack of childcare during depression visits, no time for visits, or fear that the infant might be taken away. Interventions that address these treatment barriers (e.g., nurse phone calls exploring reasons for non-treatment, patient and physician education on treatment risks and benefits, or cultural liaisons for women of diverse cultural/ethnic backgrounds) should be explored in future studies.

Observed specialty effects – worse outcomes for women from family medicine (vs. pediatric) sites – were confounded by other factors: the family medicine clinics were all urban residency training sites, while the pediatric clinics were suburban community-based clinics. Therefore, our specialty-based differences could be based on socioeconomic factors.

Strengths of the study include case finding during well-child visits in pediatric and family medicine clinics, low drop-out rate, depression diagnoses based on a reference standard (SCID interview), quantitative comparison of SCID-based depression diagnosis to self-diagnosis, use of randomized controlled trial design with a practical stepped collaborative care intervention, and our finding that the intervention positively impacted depressed mothers’ knowledge of their diagnosis and their treatment. Weaknesses include our lower than expected participation rate, specialty effects being intertwined with residency training and socioeconomic characteristics, modest number of SCID-diagnosed women, and as a result, the apparent absence of treatment effect on health outcomes. Future studies exploring this intervention with larger numbers of depressed women would be useful.

In conclusion, this study found that the stepped care intervention increased mothers’ recognition of their depression diagnosis, and improved rates of treatment. In addition, formal diagnostic procedures (e.g., SCID interviews) missed many women whose depressed mood interfered with their psychological health and daily functioning.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Dwenda Gjerdingen, Department of Family Medicine & Community Health University of Minnesota.

Scott Crow, Department of Psychiatry University of Minnesota.

Patricia McGovern, School of Public Health University of Minnesota.

Michael Miner, Department of Family Medicine & Community Health University of Minnesota.

Bruce Center, Department of Family Medicine & Community Health University of Minnesota.

References

- 1.Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, Brody S, Miller WC. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 119. AHRQ Publication No. 05-E006-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Feb, 2005. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly BD. St John’s wort for depression: what’s the evidence? Hosp Med. 2001;62(5):274–6. doi: 10.12968/hosp.2001.62.5.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seehusen DA, Baldwin LM, Runkle GP, Clark G. Are family physicians appropriately screening for postpartum depression? J Am Board Fam Med. 2005;18(2):104–112. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.2.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroenke K, Spitzer RS, Williams JBW. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, Felker B, Liu CF, Hasenberg N, Heagerty P, Buchanan J, Bagala R, Greenberg D, Paden G, Fihn SD, Katon W. Effectiveness of collaborative care depression treatment in Veterans’ Affairs primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(1):9–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.11109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, Williams JW, Jr, Kroenke K, Lin EH, Harpole LH, Arean P, Levine S, Grypma LM, Hargreaves WA, Unutzer J. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomized trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ. 2006;332(7536):259–63. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38683.710255.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE, Burns MR, Winchell CW, Chin T. Application of a depression management office system in community practice: a demonstration. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(2):107–114. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Wlaker E, Simon GE, Bush T, Robinson P, Russo J. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hoffing M, Penna R, Hitchcock P, Lin EHB, Arean PA, Hegel MT, Tang L, Belin TR, Oishi S, Langston C. Collaborative Care Management of Late-Life Depression in the Primary Care Setting. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Schulberg HC. The depression care manager and mental health specialist as collaborators within primary care. Am J Geriatr. 2003;11(5):507–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katon W, Unutzer J, Fan MY, Williams JW, Schoenbaum M, Lin EH, Hunkeler EM. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(2):265–270. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, Tang L, Williams JW, Jr, Kroenke K, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hegel M, Arean P, Hoffing M, Della Penna R, Langston C, Unutzer J IMPACT Investigators. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(18):2428–2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callahan CM, Kroenke K, Counsell SR, Hendrie HC, Perkins AJ, Katon W, Noel PH, Harpole L, Hunkeler EM, Unutzer J. Treatment of depression improves physical functioning in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rost K, Smith JL, Dickinson M. The effect of improving primary care depression management on employee absenteeism and productivity: a randomized trial. Medical Care. 2004;42:1202–1210. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, Duan N, Rubenstein LV, Miranda J, Meredith LS, Carney MF, Wells K. Cost-effectiveness of practice-initiated quality improvement for depression. JAMA. 2001;286:1325–1330. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whisman MA. Marital adjustment and outcome following treatments for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(1):125–129. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G. Rethinking practitioner roles in chronic illness: the specialist, primary care physician, and the practice nurse. Gen Hosp Psychistry. 2001;23:138–144. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ugarriza DN. Group therapy and its barriers for women suffering from postpartum depression. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2004;18(2):39–48. doi: 10.1053/j.apnu.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gjerdingen D. The effectiveness of various postpartum depression treatments and the impact of antidepressant drugs on nursing infants. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:372–82. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.5.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heneghan AM, Mercer MB, Deleone NL. Will mothers discuss parenting stress and depressive symptoms with their child’s pediatrician? Pediatrics. 2004;113(3):460–467. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.First MG, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders – Clinical Version, Administration Booklet. New York: Biometrics Research Department; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gjerdingen D, Crow S, McGovern P, Miner M, Center B. Postpartum depression screening at well-child visits: validity of a two-question screen and PHQ-9. Ann Fam Med. 2009 doi: 10.1370/afm.933. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenzel A, Gorman LL, O’Hara MW, Stuart S. The occurrence of panic and obsessive compulsive symptoms in women with postpartum dysphoria: a prospective study. Arch Women Ment Health. 2001;4(1):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 28.CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) Prevalence of self-reported postpartum depressive symptoms – 17 states, 2004-2005. MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2008 Apr 11;57(14):361–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaRocco-Cockburn A, Melville J, Bell M, Katon W. Depression screening attitudes and practices among obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:892–8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muzik M, Klier CM, Rosenblum KL, Holzinger A, Umek W, Katschnig H. Are commonly used self-report inventories suitable for screening postpartum depression and anxiety disorders? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102(1):71–3. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102001071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morse CA, Buist A, Durkin S. First-time parenthood: influences on pre- and postnatal adjustment in fathers and mothers. Journal of Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2000;21(2):109–20. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinheiro RT, Magalhaes PV, Horta BL, Pinheiro KA, da Silva RA, Pinto RH. Is paternal postpartum depression associated with maternal postpartum depression? Population-based study in Brazil. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006 Mar;113(3):230–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts SL, Bushnell JA, Collings SC, Purdie GL. Psychological health of men with partners who have post-partum depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006 Aug;40(8):704–11. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]