Abstract

A variety of phosphodiesterases hydrolyze and terminate the effects of the intracellular second messenger 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Phosphodiesterase subtype 4 (PDE4) is particularly abundant in the brain and has been imaged with 11C-(R)-rolipram, a selective inhibitor of PDE4. We sought to measure in vivo both the binding site density (Bmax) and the radioligand affinity (1/KD) of 11C-(R)-rolipram in the rat brain. We also studied 2 critical factors in small-animal PET scans: the influence of anesthesia and the difference in binding under in vivo and in vitro conditions.

Methods

In vivo, Bmax and KD were measured in PET saturation experiments by the administration of 11C-(R)-rolipram and various doses of carrier (R)-rolipram in conscious and isoflurane-anesthetized rats. The metabolite-corrected arterial input function was measured in each scan. To image conscious rats, the head of the rat was fixed in a holder and the animals were trained to comply with this apparatus. Bound and free (R)-rolipram levels were calculated under transient equilibrium conditions (i.e., at the time of peak specific binding).

Results

The Bmax and KD of conscious rats were significantly greater than those of anesthetized rats, by 29% and 59%, respectively. In addition, the in vitro KD was 3–7 times greater than was the in vivo KD, although the Bmax was similar in both conditions.

Conclusion

The in vivo Bmax and KD of (R)-rolipram were successfully measured in both conscious and anesthetized rats. KD was affected to a greater extent than was Bmax by the 2 conditions. That is, KD was increased in the conscious rat, compared with in the anesthetized rat, and KD was increased in vitro, compared with in vivo. The current study shows that the rat, a readily available species for research, can be used to measure in vivo both affinity and density of radioligand targets, which can later be directly assessed with standard in vitro techniques.

Keywords: small-animal PET, isoflurane, compartmental analysis, transient equilibrium, cAMP

A prevalent second messenger, 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) mediates the signal transduction of several neurotransmitters including dopamine, epinephrine, histamine, and adenosine. Notably, a large body of literature indicates that the cAMP pathway plays an important role in psychiatric illnesses, including mood disorders (1) and drug addiction (2). Several phosphodiesterases (PDEs) metabolize cAMP and thereby terminate the actions of this widespread second messenger. Among PDEs, PDE subtype 4 (PDE4) is selective for cAMP and highly abundant in the brain (3). In addition, PDE4 has been successfully imaged with PET in the rat (4), pig (5), nonhuman primate (6), and human (7,8) brains by 11C-labeling of the more active enantiomer of an inhibitor of PDE4, namely, (R)-rolipram.

We previously quantified the in vivo binding of 11C-(R)-rolipram in the rat brain using compartmental modeling and a metabolite-corrected arterial input function (4). We used high-specific-activity 11C-(R)-rolipram and measured binding potential, which is a product of binding site density (Bmax) and radioligand affinity (1/KD). In the current study, we extended this work by injecting the radioligand at various specific activities to measure Bmax and KD separately. Although such experiments have been performed in larger animals, to our knowledge this study is the first to measure in vivo Bmax and KD in rats, a readily available species for research.

In addition to performing a more thorough quantification, we studied 2 important factors in PET: the influence of anesthesia and the difference in binding between in vivo and in vitro conditions. Although the influence of anesthesia on 11C-(R)-rolipram binding is unknown, several studies have shown that anesthesia may influence the binding or uptake of brain molecular imaging agents (9–11). Momosaki et al. developed a new method to image rats without anesthesia by training them to remain still in a head holder during the imaging session (12). In the current study, we used a slightly modified head holder and performed in vivo saturation experiments to measure both Bmax and KD in conscious and anesthetized rats.

Results from the current in vivo study were compared with those from our prior in vitro experiments, which used 3H-rolipram and the brains from rats scanned with high-specific-activity 11C-(R)-rolipram (13) because rolipram binding is likely to differ between in vivo and in vitro conditions. Phosphorylation of PDE4 increases both the enzyme activity and the sensitivity of PDE4 to selective inhibition by rolipram (14,15). Furthermore, postmortem studies do not necessarily reflect the in vivo status of phosphorylation, because the tissue preparation of ordinary in vitro studies is thought to induce dephosphorylation of a variety of phosphoproteins in the brain (16).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Twenty-four male Sprague–Dawley rats (mean ± SD, 346 ± 42 g) were obtained from Taconic Farms Inc. The animals were housed in groups of 3 at 22°C–24°C and on a 12-h-light/12-h-dark schedule. Food and water were freely available.

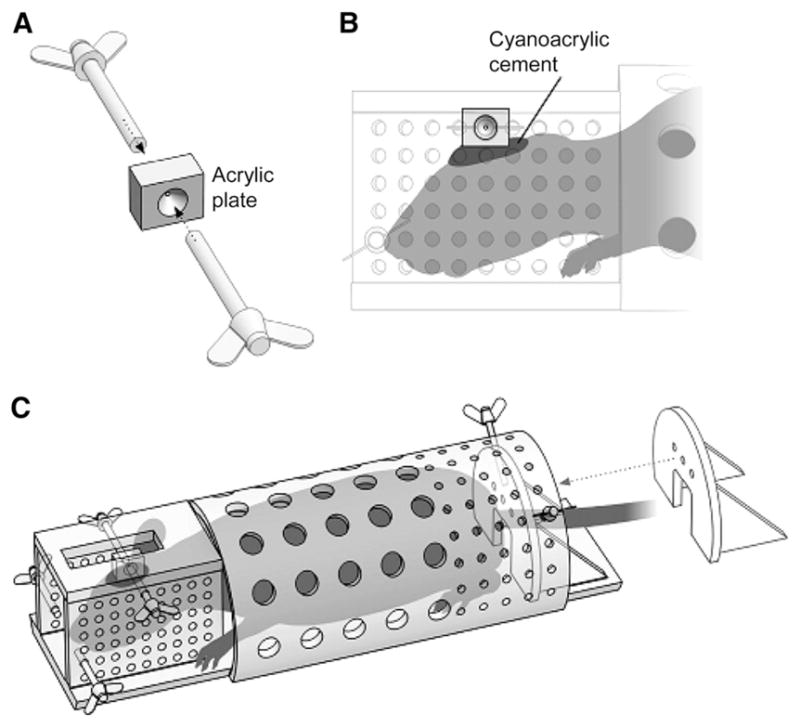

Preparation of Conscious Rats for PET

Rats were conscious when prepared for PET, as previously described (12). Minor modifications were needed in the current study because the gantry of the PET scanner was smaller than that of the scanner used in previous studies. Under isoflurane anesthesia (1.5%–2%), the rat skull was exposed, 2 stainless steel screws were inserted into the skull as anchors to hold an acrylic plate, and the plate was permanently attached to the skull using cyanoacrylic cement (Shofu Inc.). Starting the day after surgery, rats were trained to comply with a whole-body holder for PET scans (Fig. 1). The training was conducted as follows. First, rats were placed into the whole-body holder and the heads were not fixed to the holder, then rats were placed into the whole-body holder and the heads were fixed, and finally, rats were placed into the whole-body holder and the heads were fixed to hold the brain in a horizontal position. The training was performed for 2 h continuously each day for at least 10 d before the PET experiment. Our previous study had found that after similar training, the rats showed no increase in serum corticosterone levels (12).

FIGURE 1.

Head and body holder used to image conscious rats. Before PET scans, acrylic plate (A) was attached to skull using cyanoacrylic cement (B). Plate was used to fix head to holder (A and B). Rats were trained to comply with holder during PET scans (C).

PET Scans

11C-(R)-rolipram was synthesized by 11C-methylation of (R)-desmethyl-rolipram, as previously described (4). 11C-(R)-rolipram and varying amounts (0–1 mg/kg) of nonradioactive (R)-rolipram (Tocris Bioscience) were dissolved in saline (1.3 ± 0.2 mL) and intravenously infused to rats. The in vivo Bmax and KD of rolipram binding to PDE4 were measured in conscious (11 PET scans) and anesthetized (13 PET scans) rats. In each group, 3 full-blocked scans were obtained with saturating doses (0.9–1.0 mg/kg) of nonradiolabeled (R)-rolipram. In 2 conscious and 5 anesthetized rats, baseline scans were obtained without adding carrier (R)-rolipram. The baseline scans from a previous study of anesthetized rats (13) were used as controls. The remaining scans were of rats that received a coinjection of nonradiolabeled (R)-rolipram at doses of 1.0–20 μg/kg, which caused intermediate levels of binding blockade. The injected activity and specific activity of the radioligand (77.7 ± 8.2 MBq and 114 ± 46 GBq/μmol, respectively, for conscious rats and 85.0 ± 15.4 MBq and 104 ± 72 GBq/μmol, respectively, for anesthetized rats) were similar for rats in both groups. Carrier (R)-rolipram was not included in this calculation of specific activity.

The PET methods for anesthetized rats (1.5%–2% isoflurane inhalation) were identical to those in our previous paper that used only high-specific-activity 11C-(R)-rolipram (4). The PET methods for conscious rats were also identical, except that a body holder was used (Fig. 1). Animals were imaged for 60 min using the Advanced Technology Laboratory Animal Scanner (17) and a dynamic sequence of images: 6 ×20, 5 ×60, 4 ×120, 3 ×300, and 3 ×600 s. In anesthetized rats, body temperature was monitored with a rectal temperature probe and maintained between 36.5°C and 37.5°C using a heating pad. In all experiments, to measure 11C-(R)-rolipram levels by radio–high-performance liquid chromatography (4,18) a polyethylene catheter (PE-10; Aster Industries) was inserted into the femoral artery for blood sampling. Blood samples were collected in heparin-coated tubes (Thomas Scientific) 8 times between 0 and 10 min and at 20 and 40 min after the injection of 11C-(R)-rolipram. The sampling volume was 150 μL for the first 8 samples and 500 μL for the latter 2 samples (total volume, 2.2 mL).

PET Image and Kinetic Analysis

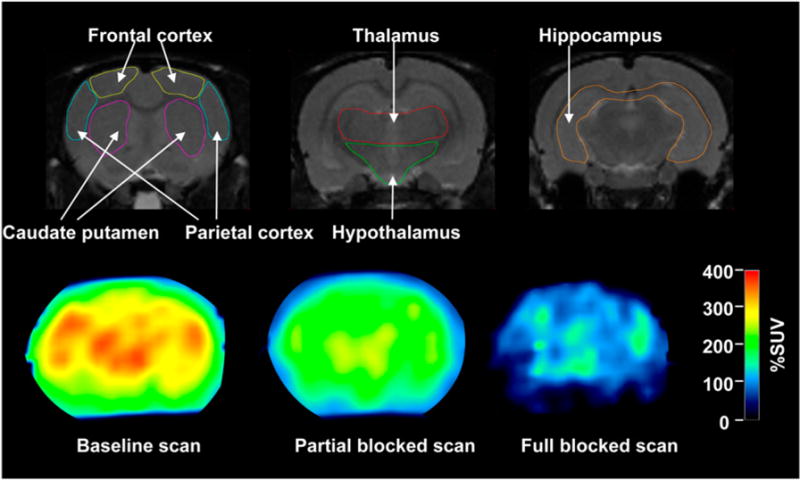

Sequential PET images were reconstructed with a 3-dimensional ordered-subset expectation maximization algorithm, achieving 1.7-mm full width at half maximum resolution (17) without the application of attenuation and scatter correction. After the reconstruction, all image frames were transformed into a standard space as defined by Schweinhardt et al. (19) using a custom template of rolipram created for our previous study (4) and Statistical Parametric Mapping 2 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, England), as reported previously. On the T2-weighted MR image in the standard space provided by Schweinhardt et al. (19), volumes of interest were drawn on the following 7 regions: caudate putamen, thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, frontal cortex, parietal cortex, and temporal cortex (Fig. 2). Although PDE4 is relatively ubiquitous in the rat brain, there are regional differences in the density detected both in vitro (20) and in vivo (4).

FIGURE 2.

T2-weighted MR (upper) and PET images obtained at 20–40 min (lower). MR images are displayed from rostral (left) to caudal (right) direction. 11C-(R)-rolipram PET scans were obtained at baseline (lower left), with 3.0 μg/kg dose of nonradiolabeled (R)-rolipram (lower middle), or saturating (1.0 mg/kg, lower right) dose of nonradiolabeled (R)-rolipram. PET images are in same location as middle of 3 MR images. Intensity of PET images is area under curve of radioactivity without including nonlabeled (R)-rolipram between 20 and 40 min. Value of 100% standardized uptake value (%SUV) is equal to concentration of radioligand that would be achieved if it were uniformly distributed in body.

Concentrations of total (R)-rolipram (i.e., 11C-(R)-rolipram plus nonradioactive (R)-rolipram) in the brain and arterial plasma were calculated from the final specific activity of 11C-(R)-rolipram summed with 11C and nonradioactive (R)-rolipram and were expressed as percentage standardized uptake value (%SUV), which normalizes for injected activity and body weight.

| Eq. 1 |

After a bolus injection of 11C-labeled and nonlabeled (R)-rolipram, specific binding levels of (R)-rolipram changed over time. The concentrations of specifically bound and free (R)-rolipram in the brain were measured at the time of transient equilibrium, that is, when specifically bound (R)-rolipram reached maximal concentration to draw a saturation curve. The original method by Farde et al. (21) determined the peak concentration of specifically bound ligand by subtracting a time–activity curve in a binding site–free region from that in regions with the binding site. Because 11C-(R)-rolipram does not have a binding-free region in the brain, the peak concentration of specifically bound rolipram was determined kinetically, by a method similar to that of Slifstein et al. (22). Time–activity curves of specifically bound and nondisplaceable compartments were computed using a 2-tissue-compartment model and fixing nondisplaceable distribution volume (K1/k2) equal to the total distribution volume in the fully blocked scans (Fig. 3). Concentrations of bound and free radioligand were determined when the specifically bound compartment reached its peak value. The concentration of free radioligand in brain was calculated from the concentration of radioactivity in the nondisplaceable compartment at transient equilibrium ( ) and the plasma-free fraction (fP). Under equilibrium conditions and for radioligands that cross the blood–brain barrier by passive diffusion only, the concentration of free ligand (i.e., not bound to proteins) is the same in arterial plasma and in the nondisplaceable compartment. Therefore, the concentration of free (R)-rolipram in the nondisplaceable compartment (CFND) was calculated as follows:

| Eq. 2 |

where VND is the nondisplaceable distribution volume (23), and fP was 30.5% ± 3.1%, as determined by an ultrafiltration method in 5 control animals from our previous study (13).

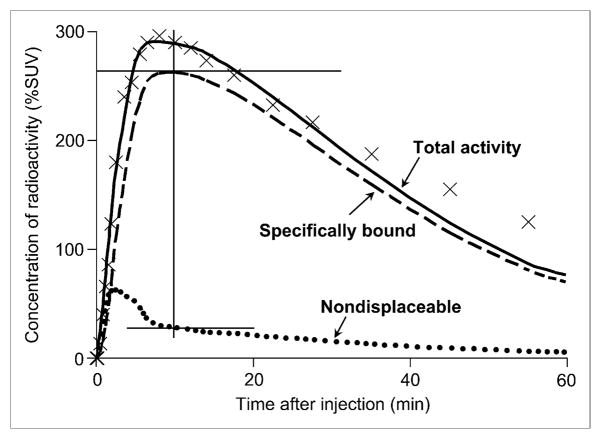

FIGURE 3.

Concentration of radioactivity in hippocampus of conscious rat and 2-compartment fitting. Total concentration of radioactivity in hippocampus (×) and serial concentrations of 11C-(R)-rolipram in arterial plasma (not shown) were fit with 2-tissue-compartment model ( ). The 2 tissue compartments were composed of specifically bound (

). The 2 tissue compartments were composed of specifically bound ( ) and nondisplaceable uptake (●●●). Concentrations of bound (R)-rolipram were measured when specific binding reached to peak (superior cross hair). At same time point, free concentrations were calculated, in part, on the basis of uptake in nondisplaceable compartment (inferior cross hair,

). In this study, peak specific uptake occurred at approximately 10 min, at which time specific binding was approximately 262% SUV, and nondisplaceable uptake was approximately 27% SUV.

) and nondisplaceable uptake (●●●). Concentrations of bound (R)-rolipram were measured when specific binding reached to peak (superior cross hair). At same time point, free concentrations were calculated, in part, on the basis of uptake in nondisplaceable compartment (inferior cross hair,

). In this study, peak specific uptake occurred at approximately 10 min, at which time specific binding was approximately 262% SUV, and nondisplaceable uptake was approximately 27% SUV.

Because true equilibrium conditions could be achieved with a bolus plus constant infusion of radioligand, we performed a simulation study using data obtained from our previous study (4). The simulation indicated that approximately 120 min were required to achieve true equilibrium. However, the concentration of 11C-(R)-rolipram in plasma at this time would likely be too low to measure accurately. Therefore, we used the transient equilibrium method in the present study.

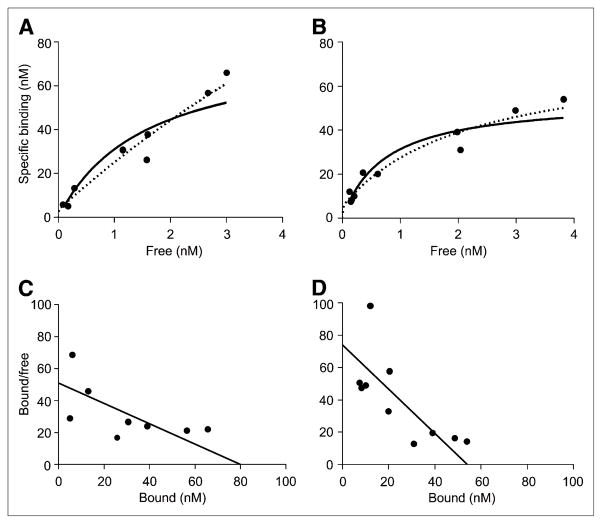

Kinetic analyses were performed using PMOD 2.90 (pixelwise modeling software; PMOD Technologies Ltd.). In vivo Bmax and KD in each brain region were measured by nonlinear least-squares fitting of 1- and 2-binding-site models applied to the saturation data (Fig. 4). In this fitting, data were weighted to minimize the sum of squares of errors relative to the observed values. The nonlinear fitting was performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (Graph-Pad Software, Inc.).

FIGURE 4.

Saturation analysis of (R)-rolipram binding measured with PET in hippocampus of conscious (A) and anesthetized (B) rats, where goodness of fit was at medium level among all regions. These graphs plot specific binding as a function of free radioligand concentration. The 1- ( ) and 2- (■■■) binding-site models did not differ based on goodness of fit in either conscious (P = 0.495) or anesthetized (P = 0.399) rats. Thus, data did not justify use of 2-site binding model. For conventional display, Scatchard plots were created using Bmax and KD obtained from non-linear fitting of 1-site model in hippocampus of conscious (C) and anesthetized (D) rats.

) and 2- (■■■) binding-site models did not differ based on goodness of fit in either conscious (P = 0.495) or anesthetized (P = 0.399) rats. Thus, data did not justify use of 2-site binding model. For conventional display, Scatchard plots were created using Bmax and KD obtained from non-linear fitting of 1-site model in hippocampus of conscious (C) and anesthetized (D) rats.

In Vitro Rolipram Binding Assay

In vivo Bmax and KD were compared with previously reported in vitro results obtained from 5 rats used in baseline scans under isoflurane anesthesia (13). In brief, in vitro Bmax and KD were measured in the frontal cortex, hippocampus, and diencephalon (thalamus and hypothalamus) from the binding of racemic 3H-rolipram (GE Healthcare) to homogenates of membrane and cytosolic fractions using previously reported methods (24). Bmax and KD in whole tissue were calculated as weighted averages of the results in membrane and cytosolic fractions. The weighting was done on the basis of the total protein content in each fraction (13). (R)-rolipram has 20 times greater affinity than does (S)-rolipram (25). The R-enantiomer was used for PET, but the racemic mixture was used for homogenate binding. Therefore, the in vitro KD values of the R-enantiomer were estimated by dividing the KD values (nM) of the racemic mixture by a factor of 2. In vitro Bmax values were initially obtained in a unit of femtomoles per milligram of protein. For comparison with PET results, the unit of in vitro Bmax was converted into nanomolar using the protein concentration of the homogenate solution (milligrams of protein per milliliter), total volume of the homogenate solution (milliliters), and weight of the tissue (grams). The in vitro values of Bmax and KD in the diencephalon were compared with the weighted average of in vivo values from the thalamus and hypothalamus.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Parametric and nonparametric variables were determined by the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. The statistical significance of differences was determined using unpaired Student t test (parametric) or the Mann–Whitney test (nonparametric). Goodness of fit between 1- and 2-binding-site models was assessed with the extra sum-of-squares F test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Compartmental modeling of brain and plasma data confirmed that a high percentage of the baseline binding of 11C-(R)-rolipram was specific; that is, binding could be blocked by nonradioactive (R)-rolipram (Fig. 2). For example, combining results from conscious and anesthetized rats, the total distribution volume of all 7 baseline scans was 18.1 ± 4.8 mL·cm−3, whereas the total distribution volume in all 6 fully blocked scans was 1.7 ± 0.4 mL·cm−3. Thus, these mean values show that approximately 90% of baseline uptake was specific. Furthermore, the distribution volume in fully blocked scans (which is the nondisplaceable distribution volume VND) was similar under the 2 scanning conditions: conscious (2.15, 1.38, and 1.80 mL·cm−3) and anesthetized (1.40, 1.23, and 2.07 mL·cm−3).

To determine whether anesthesia affected KD or Bmax, we obtained data with increasing binding site saturation by nonradioactive (R)-rolipram. The concentrations of free and specifically bound radioligand were obtained at transient equilibrium from a 2-tissue-compartment fit and the fixing of K1/k2 to the total distribution volume of fully blocked scans (Fig. 3). The calculated concentrations of free and specifically bound ligand showed wide ranges (free, 0.07–5.68 nM; bound, 3.63–88.3 nM), which allowed measurement of Bmax and KD (Fig. 4). The concentration of free radioligand calculated with Equation 2 was 0.08–0.17 nM in the baseline scans and 0.29–3.00 nM in the partially blocked scans.

The nonlinear least-squares fitting of these in vivo values of bound and free ligand allowed us to calculate Bmax and KD and to estimate whether binding existed in both high-and low-affinity states. The fits of 1- and 2-binding-site models were not statistically different in any region under either conscious or anesthetized conditions (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the 2-binding-site model poorly identified all variables, as indicated by a covariance greater than 0.9999 for at least 2 of 4 variables (Bmax and KD of high- and low-affinity binding sites) in 5 among a total of 14 fits. In addition, the 1-binding-site model showed a good fit with R2 = 0.85 ± 0.04. Therefore, Bmax and KD were measured by the 1-binding-site model. This model identified Bmax and KD with an [SE]/[best-fit value] of 22% ± 6% and 36% ± 10%, respectively.

Both conscious and isoflurane-anesthetized animals showed regional differences in Bmax and KD. In conscious rats, Bmax and KD ranged from 64.7 to 93.3 nM and from 1.10 to 1.57 nM, respectively (Table 1). Bmax and KD showed a similar magnitude of regional variability in anesthetized rats. However, in every region, conscious animals had a larger Bmax (29% on average) and KD (59% on average) than did anesthetized animals. Furthermore, both Bmax (P = 0.019) and KD (P = 0.004) values of conscious rats were significantly greater than those of anesthetized rats.

TABLE 1.

In Vivo Bmax and KD of 11C-(R)-Rolipram Measured in Brain Regions of Conscious and Anesthetized Rats

| Bmax (nM) |

KD (nM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Conscious Anesthetized Conscious Anesthetized | |||

| Caudate putamen | 93.3 | 68.6 | 1.46 | 0.81 |

| Thalamus | 70.0 | 57.4 | 1.17 | 0.91 |

| Hypothalamus | 61.2 | 33.9 | 1.53 | 0.59 |

| Hippocampus | 79.7 | 54.3 | 1.57 | 0.73 |

| Frontal cortex | 68.3 | 64.8 | 1.10 | 0.97 |

| Parietal cortex | 72.6 | 64.6 | 1.36 | 1.09 |

| Temporal cortex | 64.7 | 52.8 | 1.25 | 0.84 |

Each set of Bmax and KD values was calculated by nonlinear least-squares fitting of 1-binding-site model applied to saturation data. Significant differences were found between conscious and anesthetized rats in both mean Bmax (P = 0.019) and KD (P = 0.004) values by Student t test in all regions.

These in vivo Bmax and KD values were compared with previously reported in vitro values that were obtained in samples from animals used in baseline scans under isoflurane anesthesia. Because of the variability in KD among publications (5,13,24,25), it is important to compare in vitro and in vivo results in the same animals. The KD values from in vitro binding assays were 3–7 times greater than those obtained from in vivo PET measurements in both conscious and anesthetized animals. In contrast, in vitro Bmax values did not markedly differ from in vivo measures in either conscious or isoflurane-anesthetized animals (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Bmax and KD of (R)-Rolipram Measured In Vivo and In Vitro in Regions of Rat Brain

| Bmax (nM) |

KD (nM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo |

In vivo |

|||||

| Region | Conscious | Anesthetized | In vitro | Conscious | Anesthetized | In vitro |

| Frontal cortex | 68.3 | 64.8 | 84 ± 6 | 1.10 | 0.97 | 5.5 ± 0.3 |

| Hippocampus | 79.7 | 54.3 | 66 ± 6 | 1.57 | 0.73 | 5.4 ± 0.3 |

| Diencephalon | 66.7 | 48.6 | 81 ± 8 | 1.31 | 0.79 | 6.1 ± 0.3 |

Values from in vitro studies are mean ± SD. In vitro KD published in Fujita et al. (13) measured with racemic 3H-rolipram was divided by 2 to calculate KD of (R)-rolipram.

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates the feasibility of separately measuring the Bmax and 1/KD of 11C-(R)-rolipram binding to PDE4 in vivo. The study also investigates 2 critical factors in the measurement of animal PET scans: the effects of anesthesia and the differences between in vivo and in vitro conditions. We previously reported the in vivo quantitation of rolipram binding potential, which is the product of Bmax and 1/KD. In the current study, we extend our previous work by coinjecting variable doses of nonradioactive (R)-rolipram, which allowed us to separately calculate Bmax and KD in both conscious and anesthetized rats. A comparison of the results for conscious and anesthetized rats showed highly significant differences in KD. We also compared in vivo Bmax and KD with previously reported in vitro values from the same animals and found large differences in KD but similar Bmax values (Table 2). In combination, our results suggest that KD is more sensitive than Bmax to the status of the tissue.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate that Bmax and KD can be measured using PET in rats. In vivo Bmax and KD have been measured separately for other radioligands with PET using only larger animals, such as the pig (26), nonhuman primates (22), and humans (21). Rats are useful in experimental models because they can be sacrificed at modest expense, and their brain tissue can be used to compare in vivo and in vitro results. For example, we found that the Bmax of rolipram was similar in rats under in vivo and in vitro conditions (Table 2), suggesting that most PDE4 binding sites are available in vivo to bind radioligand.

Recently developed methods of imaging conscious non-human primates have been used to study behavior and the effects of anesthesia (11). Momosaki et al. (12) extended such methods to rats by training them; however, even after training, rats may make small head movements that are barely visible. In future studies, quantitative evaluation of head movements and mathematic correction of the data for such movements might improve the accuracy of the data. Scans with isoflurane anesthesia were obtained without a holder so the nose cone for inhalation could be stably attached. Because attenuation correction was not performed in the current study, as in most other small-animal PET studies, the data for the conscious animals may be slightly more attenuated by the holder than data for the anesthetized animals. Assuming there are no holes in the holder, and based on the density (1.19 g/cm3) and thickness (~0.5 cm) of the material of the holder (polymethyl methacrylate), attenuation caused by the holder would be approximately 10%. Attenuation would decrease concentrations of both specifically bound and free ligand and would make both Bmax and KD smaller. However, in our study, conscious rats showed greater Bmax and KD. Therefore, the holder was unlikely to have had any meaningful impact on our results.

Although Bmax had similar values under in vivo and in vitro conditions, the affinity of 11C-(R)-rolipram was greater (i.e., the KD was smaller) under in vivo than under in vitro conditions. The higher in vivo affinity could have been caused by several factors, including anesthesia, local environment, protein–protein interactions (3), temperature differences (in vivo, 37°C; in vitro, 30°C), and the phosphorylation state of PDE4. Protein kinase A phosphorylates PDE4, which then has 3- to 8-fold higher enzyme activity and sensitivity to inhibition by rolipram (14,15) than the nonphosphorylated form. In addition, although the effects of anesthetics on phosphorylation status of PDE4 are unknown, anesthetics change the phosphorylation status of several other proteins in signal transduction systems (27,28). Thus, 11C-(R)-rolipram might be capable of monitoring the phosphorylation state of PDE4 under varying in vivo conditions (e.g., at baseline and after pharmacologic modulation of protein kinase A). If phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of PDE4 have markedly different affinities, the presence of 2 binding sites would be expected. Although the fitting for the saturation curve (Fig. 4) showed the presence of only 1 site, our studies had only 8–10 points, which is probably inadequate with the noise of the in vivo data to distinguish 1 from 2 binding sites. High-and low-affinity rolipram binding sites have been proposed using recombinant PDE4 (29), but most in vitro (24,30) and in vivo (5) studies show the presence of a single binding site for rolipram. Thus, if phosphorylation can be measured in vivo with 11C-(R)-rolipram, it would most likely be seen as an overall change in affinity of a single site, as we found for the effect of isoflurane.

One limitation of this study is that we measured binding at transient equilibrium (i.e., time of peak specific binding), which is likely not equivalent to conditions at true equilibrium. For example, we assumed that at transient equilibrium the concentrations of free radioligand were equal in the specific binding compartment and in the simulated nondisplaceable compartment. A more accurate method to achieve true equilibrium would be to use a bolus plus constant infusion of radioligand at varying specific activities. Unfortunately, our simulations suggested that the concentrations of radioligand in plasma at late time points would be too low to measure accurately. The magnitude of error caused by the transient equilibrium method is difficult to estimate. Thus, the differences we found between in vitro and in vivo binding parameters should be interpreted cautiously. However, the differences we found in affinity between conscious and anesthetized states were likely not affected by this approach, because any errors would pre-sumably apply fairly equally to the measurement of KD in conscious and anesthetized conditions.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated the feasibility of using in vivo PET to separately measure Bmax and 1/KD in conscious and anesthetized rats. Imaging conscious animals is important to the study of brain function without the interference of anesthetics. Because postmortem studies can be performed easily in rats, PET followed by tissue harvesting can help determine which in vitro parameters most accurately reflect in vivo conditions. The 1/KD of (R)-rolipram showed much greater differences than did Bmax between conscious and anesthetized rats and between in vivo and in vitro conditions. Thus, affinity is sensitive to the status of tissue and may be an in vivo biomarker of enzyme activity, which, for example, can be modulated by phosphorylation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Gladding, Matthew Crescenzo, Jeih-San Liow, Edward Tuan, and Jonathan Gourley for assisting with PET experiments and data processing; Jurgen Seidel and Michael Green for developing the small-animal PET scanner; PMOD Technologies (Zurich, Switzerland) for providing its image-analysis and modeling software; Antony Gee for providing the precursor of 11C-(R)-rolipram; David Luckenbaugh for assisting with statistical analyses; Alan Hoofring and Ethan Tyler for drawing schematic diagrams; Ioline Henter for editorial assistance; and Ronald Duman for helpful discussions. This research was supported by the Intramural Program of NIMH (project Z01-MH-002795-07).

References

- 1.Duman RS, Heninger GR, Nestler EJ. A molecular and cellular theory of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:597–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830190015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nestler EJ, Aghajanian GK. Molecular and cellular basis of addiction. Science. 1997;278:58–63. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell JM, Zhang HT. Antidepressant effects of inhibitors of cAMP phosphodiesterase (PDE4) Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujita M, Zoghbi SS, Crescenzo MS, et al. Quantification of brain phosphodiesterase 4 in rat with (R)-[11C]rolipram-PET. Neuroimage. 2005;26:1201–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker CA, Matthews JC, Gunn RN, et al. Behaviour of [11C]R(2)- and [11C]S(1)-rolipram in vitro and in vivo, and their use as PET radiotracers for the quantificative assay of PDE4. Synapse. 2005;55:270–279. doi: 10.1002/syn.20114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukada H, Harada N, Ohba H, Nishiyama S, Kakiuchi T. Facilitation of dopaminergic neural transmission does not affect [11C]SCH23390 binding to the striatal D1 dopamine receptors, but the facilitation enhances phosphodiesterase type-IV activity through D1 receptors: PET studies in the conscious monkey brain. Synapse. 2001;42:258–265. doi: 10.1002/syn.10013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DaSilva JN, Lourenco CM, Meyer JH, Hussey D, Potter WZ, Houle S. Imaging cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase-4 in human brain with R-[11C]rolipram and positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:1680–1683. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0950-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthews JC, Passchier J, Wishart MO, et al. The characterisation of both the R and S enantiomers of [11C]rolipram in man [abstract] J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23(suppl 1):678J. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hildebrandt IJ, Su H, Weber WA. Anesthesia and other considerations for in vivo imaging of small animals. ILAR J. 2008;49:17–26. doi: 10.1093/ilar.49.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tokugawa J, Ravasi L, Nakayama T, et al. Distribution of the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist [18F]FPWAY in blood and brain of the rat with and without isoflurane anesthesia. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:259–266. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onoe H, Inoue O, Suzuki K, et al. Ketamine increases the striatal N-[11C]methylspiperone binding in vivo: positron emission tomography study using conscious rhesus monkey. Brain Res. 1994;663:191–198. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91263-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Momosaki S, Hatano K, Kawasumi Y, et al. Rat-PET study without anesthesia: anesthetics modify the dopamine D1 receptor binding in rat brain. Synapse. 2004;54:207–213. doi: 10.1002/syn.20083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita M, Imaizumi M, D’Sa C, et al. In vivo and in vitro measurement of brain phosphodiesterase 4 in rats after antidepressant administration. Synapse. 2007;61:78–86. doi: 10.1002/syn.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sette C, Conti M. Phosphorylation and activation of a cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase: involvement of serine 54 in the enzyme activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16526–16534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann R, Wilkinson IR, McCallum JF, Engels P, Houslay MD. cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase HSPDE4D3 mutants which mimic activation and changes in rolipram inhibition triggered by protein kinase A phosphorylation of Ser-54: generation of a molecular model. Biochem J. 1998;333:139–149. doi: 10.1042/bj3330139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Callaghan JP, Sriram K. Focused microwave irradiation of the brain preserves in vivo protein phosphorylation: comparison with other methods of sacrifice and analysis of multiple phosphoproteins. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;135:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seidel J, Vaquero JJ, Green MV. Resolution uniformity and sensitivity of the NIH ATLAS small animal PET scanner: comparison to simulated LSO scanners without depth-of-interaction capability. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2003;50:1347–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoghbi SS, Shetty HU, Ichise M, et al. PET imaging of the dopamine transporter with 18F-FECNT: a polar radiometabolite confounds brain radioligand measurements. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:520–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schweinhardt P, Fransson P, Olson L, Spenger C, Andersson JL. A template for spatial normalisation of MR images of the rat brain. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;129:105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez-Torres S, Miro X, Palacios JM, Cortes R, Puigdomenech P, Mengod G. Phosphodiesterase type 4 isozymes expression in human brain examined by in situ hybridization histochemistry and [3H]rolipram binding autoradiography: comparison with monkey and rat brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2000;20:349–374. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farde L, Eriksson L, Blomquist G, Halldin C. Kinetic analysis of central [11C]-raclopride binding to D2 dopamine receptors studied with PET: a comparison to the equilibrium analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9:696–708. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slifstein M, Hwang DR, Huang Y, et al. In vivo affinity of [18F]fallypride for striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptors in nonhuman primates. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;175:274–286. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1830-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Y, Zhang HT, O’Donnell JM. Inhibitor binding to type 4 phosphodiesterase (PDE4) assessed using [3H]piclamilast and [3H]rolipram. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:565–572. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.47407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider HH, Schmiechen R, Brezinski M, Seidler J. Stereospecific binding of the antidepressant rolipram to brain protein structures. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;127:105–115. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minuzzi L, Olsen AK, Bender D, et al. Quantitative autoradiography of ligands for dopamine receptors and transporters in brain of Gottingen minipig: comparison with results in vivo. Synapse. 2006;59:211–219. doi: 10.1002/syn.20234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bickler PE, Fahlman CS. The inhaled anesthetic, isoflurane, enhances Ca21-dependent survival signaling in cortical neurons and modulates MAP kinases, apoptosis proteins and transcription factors during hypoxia. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:419–429. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000223671.49376.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder GL, Galdi S, Hendrick JP, Hemmings HC., Jr General anesthetics selectively modulate glutamatergic and dopaminergic signaling via site-specific phosphorylation in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobitz S, McLaughlin MM, Livi GP, Burman M, Torphy TJ. Mapping the functional domains of human recombinant phosphodiesterase 4A: structural requirements for catalytic activity and rolipram binding. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:891–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang HT, Zhao Y, Huang Y, et al. Antidepressant-like effects of PDE4 inhibitors mediated by the high-affinity rolipram binding state (HARBS) of the phosphodiesterase-4 enzyme (PDE4) in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:209–217. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]