Summary

The checkpoint proteins Rad9, Rad1, and Hus1 form a clamp-like complex which plays a central role in the DNA damage-induced checkpoint response. Here we address the function of the 9-1-1 complex in Drosophila. We decided to focus our analysis on the meiotic and somatic requirements of hus1. For that purpose, we created a null allele of hus1 by imprecise excision of a P-element found 2 kb from the 3′ of the hus1 gene. We found that hus1 mutant flies are viable, but the females are sterile. We determined that hus1 mutant flies are sensitive to HU and MMS but not to X-rays, suggesting that hus1 is required for the activation of an S phase checkpoint. We also found that hus1 is not required for the G2/M checkpoint and for post-irradiation induction of apoptosis. We subsequently studied the role of hus1 in activation of the meiotic checkpoint and found that the hus1 mutation suppresses the dorsal-ventral pattering defects caused by mutants in DNA repair enzymes. Interestingly, we found that the hus1 mutant exhibits similar oocyte nuclear defects as those produced by mutations in DNA repair enzymes. These results demonstrate that hus1 is essential for the activation of the meiotic checkpoint and that hus1 is also required for the organization of the oocyte DNA, a function that might be independent of the meiotic checkpoint.

Keywords: Drosophila, DNA damage checkpoint, meiotic checkpoint, Hus1

Introduction

In many cell types specific checkpoint mechanisms exist that monitor the integrity of the chromosomes. These checkpoints coordinate cell cycle progression with DNA repair to ensure the distribution of accurate copies of the genome to daughter cells. If left unrepaired, chromosomal lesions can lead to genomic instability, a major contributing factor in the development of cancer and other genetic diseases. The DNA damage checkpoint response system involves a signal transduction pathway consisting of sensors, transducers and effectors (Dasika et al., 1999; Zhou and Elledge, 2000). Damaged DNA is initially sensed by a complex comprised of Hus1, Rad1, and Rad9 and the associated protein Rad17. Computer modeling suggests that Rad9, Hus1 and Rad1 (also called 9-1-1 complex) form a doughnut-like heteromeric PCNA complex that can be loaded directly onto damaged DNA (Rauen et al., 2000; Venclovas and Thelen, 2000; Bermudez et al., 2003). The signal transducers are comprised of four sets of conserved protein families. One family is composed of ATM and ATM-Rad3-related (ATR) proteins. Downstream of these proteins are two sets of checkpoint kinases, the Chk1 and the Chk2 kinases and their homologues. The fourth conserved family is that of the BRCT-repeat containing proteins. Finally, a diverse range of effector proteins execute the function of the DNA damage response, which can lead to cell cycle arrest, apoptosis or activation of the DNA repair machinery (reviewed in Harrison and Haber, 2006).

A number of checkpoint proteins that were initially characterized in budding and fission yeast, have counterparts in Drosophila, C. elegans and mammals, demonstrating the conservation of these surveillance mechanisms. Several checkpoint proteins have been characterized in Drosophila, mainly the ATM/ATR and the Chk1/Chk2 transducer family of proteins. An ATR homolog in Drosophila is encoded by mei-41 (Hari et al., 1995). mei-41 is essential for the DNA damage checkpoint in larval imaginal discs and neuroblasts and for the DNA replication checkpoint in the embryo (Hari et al., 1995; Brodsky et al., 2000; Garner et al., 2001). mei-41 also has an essential role during early nuclear divisions in embryos (Sibon et al., 1999). In addition, mei-41 also plays important roles during meiosis, where it has been proposed to monitor double-strand-break repair during meiotic crossing over, to regulate the progression of prophase I, and to enforce the metaphase I delay observed at the end of oogenesis (Ghabrial and Schüpbach 1999; McKim et al., 2000). Drosophila ATM and ATR orthologs are required for different functions. In Drosophila, recognition of chromosome ends by ATM prevents telomere fusion and apoptosis by recruiting chromatin-modifying complexes to telomeres (Song et al., 2004; Bi et al., 2004; Silva et al., 2004; Oikemus et al., 2004). It has also been shown that dATM and mei-41 have temporally distinct roles in G2 arrest after irradiation (Song et al., 2004).

A Chk1 homolog in Drosophila is encoded by grapes (Fogarty et al., 1997). Similarly to mei-41, grapes is required to delay the entry into mitosis in larval imaginal discs after irradiation and to delay the entry into mitosis after incomplete DNA replication in the embryo (Sibon et al., 1997; Brodsky et al., 2000). The Drosophila Chk2 homolog (also designated loki or Dmnk) regulates multiple DNA repair and apoptotic pathways following DNA damage (Xu et al., 2001; Peters et al., 2002; Masrouha et al., 2003; Brodsky et al., 2004). It plays an important role in a mitotic checkpoint in syncytial embryos (Xu and Du, 2003) and is important in centrosome inactivation (Takada et al., 2003). Like Mei-41, DmChk2 also plays an important role in monitoring double-strand-break repair during meiotic crossing over (Abdu et al., 2002). Although our understanding of the role of DNA damage proteins is increasing, there is still a lack of information on the function of the Drosophila PCNA-like complex, 9-1-1.

In this study, we analyzed the interaction between the Drosophila Rad9, Hus1 and Rad1 proteins using a yeast two-hybrid assay. We were able to detect interaction between Hus1 and Rad9 or Rad1, but not between Rad9 and Rad1. We decided to focus our analysis on the meiotic and somatic requirement of Hus1. A null allele of hus1 was created by imprecise excision of a P-element. We observed sensitivity of hus1 mutants to hydroxyurea (HU) and to methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) but not to X-ray irradiation. This implies that hus1 is required for the DNA replication checkpoint. The ability of a mutation in hus1 to suppress the eggshell polarity defects detected in mutants affecting double strand DNA repair enzymes demonstrates that it is required for the activation of the meiotic checkpoint that leads to a strong reduction in the translation of gurken mRNA. The similarity of the defects in the organization of the DNA in the oocyte nucleus between hus1 mutants and mutations in DNA repair enzymes suggest that hus1 may act upstream of the DNA repair machinery.

Material and Methods

Drosophila strains

Oregon-R was used as wild-type control. The following mutant and transgenic flies were used: spn-BBU (Ghabrial et al., 1998), okraAA (Ghabrial et al., 1998), mei-41D3 (Hari et al., 1995), and chk2P6 (Abdu et al., 2002), Df(3R)110 (Bloomington stock center), P{GT1}BG00590 and P{SUPor-P}KG07223 (Bellen et al., 2004). Marker mutations and balancer chromosomes are described in the Drosophila Genome Database at http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu)

Yeast two hybrid

The two-hybrid screen was performed using the Hybrid Hunter System (Invitrogen). The entire coding sequence of Hus1 was amplified by PCR using modified primers to create an XhoI restriction site at the 5′ end and a SalI site at the 3′ end. The resulting PCR product was cut using XhoI and SalI and was cloned into the pHybLex/Zeo vector (LexA DBD, which was used as bait). The entire coding sequence of Rad1 as well as a truncated version (from amino acid 35) was introduced into the pYESTrp2 vector (B42 AD, which was used as prey) as Sac1-EcoR1. The entire coding sequence of Rad9 was cloned into the pYESTrp2 vector as HindIII-EcoRI, and also cloned into the pHybLex/Zeo vector as SacI-XhoI. Positive interactions were detected by selecting on SD-His plates, followed by a second screen for β-galactosidase expression.

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was obtained from 10–15 ovaries using Trizol Reagent® (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RT–PCR was performed using SuperScript™ One-Step RT–PCR with Platinum® Taq (Invitrogen). Control experiments, using Platinum® Taq minus RT, were performed to confirm the absence of contaminating genomic DNA. No signal was ever obtained from the RNA preparation. The primers that were used are: 1) Rad1 forward GGATGACTGATGTGGAGCCATC and reverse CAGGGGATCGCCCTTATCCCTG , 2) Hus1 forward GCCTCGGTGCTTACGTCGTCTTCAAC, reverse ACATACAAACAGCTGGCAGAATAG and 3) Rad9 forward TTGCCAATGAAATACACTTTAG, reverse CCACGGATTATATTCGGCATC.

Transgenic flies

To make the pUASp-Hus1 fusion construct the entire coding sequence of hus1 was amplified by PCR using modified primers to create a KpnI restriction site at the 5′ end and a NotI site at the 3′ end. The resulting PCR product was cut using KpnI and NotI and was cloned into pUASp. P-element-mediated germ-line transformation of this construct was carried out according to standard protocols (Spradling and Rubin, 1982). Hus1 was expressed in the ovaries using an Act5C-Gal4 expression system.

DNA staining of ovaries

For karysome staining, ovaries were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 200 μl 4% paraformaldehyde in PBST (PBS + 0.2% Tween 20) plus 600 μl heptane for 20 minutes. Ovaries were incubated in 0.2 mg/ml RNase A and a 1:5000 dilution of OliGreen (Molecular Probes) or 1:10,000 Hoechst (Molecular Probes) and 1μg/ml wheat-germ Agglutinin-488 (Molecular Probes) for 1 hour. After several washes, ovaries were mounted in 50% glycerol:PBS and visualized by confocal microscopy.

Creation of Hus1 mutants

Excision of P{SUPor-P}KG07223 was generated by crossing to a transposase-expressing line (Sb Δ2–3/TM6B). Seventy male progeny from this cross, of the genotype w; KG07223/ Sb Δ2–3, were then crossed to Pri/TM6B females, and 145 potential excision events were identified by the loss of the w+ marker. All of these lines were tested by genomic PCR reaction with primers that cover the first exon. Excision of P{GT1}BG00590 was done the same as above with the following modification: 167 potential excision events were identified and tested by genomic PCR reaction with primers that cover the second exon.

MMS, HU and IR sensitivity assays

Heterozygous males and females were mated in vials and eggs were collected for 24 hours at room temperature. Parents were removed and 24-48 hours later the larvae were treated with different concentrations of methyl methanesulfonate (MMS, Sigma) or hydroxyurea (HU, Sigma), or irradiated with 2500 Rads in a Faxitron X-ray cabinet. Control flies were treated with 250 μl water or not irradiated. After eclosion the percentage of mutant flies was determined, and the sensitivity was expressed as the fraction of the expected percentage of the mutant flies in the treated vial as compared to the progeny of untreated control vials. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Survival rates of hus-1 larvae and pupae

First and early second instar larvae (age: 30 +/− 12 hrs after egg laying) of appropriate genotype were selected under a dissecting microscope with GFP detection filter. The larvae were put into food vials and treated with 0.08% MMS 4-6 hrs later. Control larvae were treated with 250 μl water. White non-motile pupae were counted, later, pharate adults, and finally, hatched adults were counted.

Checkpoint and apoptosis assays

Homozygous hus137 and mei-41D3 larvae were tested for their ability to undergo cell cycle arrest after IR as described in Brodsky et al., 2000. Confocal stacks of 0.5 micron intervals were analyzed using Volocity 3DM software (Improvision). At least five discs from two separate experiments were used for quantification.

To determine the requirement of hus1 for post-irradiation induction of apoptosis during larval development, climbing homozygous larvae were mock-treated or treated with 4000 Rads. Four hours after irradiation, imaginal discs were dissected, incubated in 0.5 μg/ml acridine orange for 5 minutes, washed in PBS, and visualized with a fluorescent microscope. Representative discs are shown from one of three replicate experiments. At least five discs were analyzed per experiment.

Neuroblast chromosome squashes

Larva were treated with water or 0.025% MMS as described for MMS sensitivity assays. 4-5 days after MMS treatment larval brains of climbing third instar larva were dissected in PBS and incubated in 20 μg/ml colchicine in PBS for one hour. Brains were incubated in 0.5% sodium citrate for 10 minutes, fixed in 11:11:2 acetic acid/methanol/water, and squashed in 45% acetic acid. Slides were frozen in liquid nitrogen, incubated 20 minutes in cold ethanol and mounted in Vectashield mounting media with DAPI (Vector).

Results

Functional analysis of the Drosophila Hus1 gene

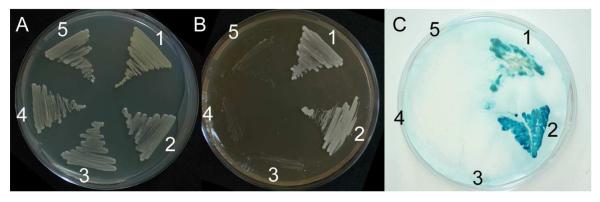

Studies in yeast and humans have shown that Rad9, Hus1, and Rad1 interact in a hetrotrimeric complex, which resembles a PCNA-like sliding clamp (reviewed in Parrilla-Castellar et al., 2004). To study the interaction between the Drosophila Rad9, Hus1 and Rad1 proteins, we performed a yeast two hybrid assay (Fig. 1) in which Hus1 was used as a bait. Our results showed that Hus1 interacts with Rad9 and Rad1 to different degrees. Whereas Hus1 and Rad1 showed strong interaction (Fig. 1 C2), only a weak interaction between Hus1 and Rad9 was detected (Fig. 1 C1). To analyze the interaction between Rad9 and Rad1, Rad9 was used as bait. No interaction between Rad1 and Rad9 was found in this assay (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Detection of the interaction between Hus1 and Rad9 or Rad1. 1, L40 bearing Hus1 in pHybLex/Zeo vector and Rad9 in pYESTrp2 vector; 2, L40 bearing Hus1 in pHybLex/Zeo vector and Rad1 in pYESTrp2 vector; 3, L40 bearing Rad9 in pYESTrp2 vector and an empty pHybLex/Zeo vector; 4, L40 bearing Hus1 in pHybLex/Zeo vector and an empty pYESTrp2 vector; 5, L40 bearing Rad1 in pYESTrp2 vector and an empty pHybLex/Zeo vector. A, Non-selective medium for detection of interaction; B, The activation of the HIS promoter was tested on plates without Histidine. C, Activation of the LacZ promoter by assay of β-galactosidase activity. Hus1 interacted either with Rad9 (B1, C1) or Rad1 (B2, C2).

Generation of null mutations in Hus1

We decided to focus our study on hus1, since there were several P-elements lines available in hus1 gene region (Bellen et al., 2004). To analyze the somatic and meiotic requirements of the Drosophila Hus1, genetic studies were initiated. We screened for transposase induced imprecise excisions by loss of the w+ marker and tested these lines by genomic PCR and DNA sequencing. Excision of the P transposon insertion, P{SUPor-P}KG07223 which is inserted 150 bases away from the 5′ of hus1 (Bellen et al., 2004) yielded one candidate mutant, hus198. This line has deletion of 230 bases, which removes the first exon. RT-PCR analysis showed that removing the first exon had no effect on the level of hus1 transcript (data not shown). To create a null allele, another P element transposon, {GT1}BG00590, which is inserted 2kb from the 3′ of hus1 gene, was mobilized (Bellen et al., 2004) and one candidate mutant, hus137, was identified. hus137 has deletion of 3297 bases which remove the entire ORF of hus1 gene and delete no other predicted transcript.

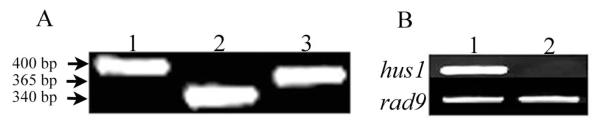

Since we were interested in understanding the role of the 9-1-1 complex in meiosis, the expression pattern of hus1, rad1 and rad9 genes during Drosophila oogenesis was studied. RT-PCR analysis showed that all three genes are expressed in Drosophila ovaries (Fig. 2 A). However, no hus1 transcript was detected in hus137 ovaries by RT-PCR analysis as compared to wild-type (Fig. 2 B), as expected from the molecular analysis, demonstrating that hus137 is a null allele. The level of rad9 transcript was used as control (Fig. 2 B). We found that hus137 mutant flies are viable however, females are sterile. This line was used for further examination of hus1 mutant phenotypes.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR detection of hus1, rad9 and rad1 transcripts in wild type and in hus137 mutant ovaries. A, detection of hus1, rad9 and rad1 transcripts in wild type ovaries. 1, hus1 transcript ; 2, rad1 transcript; 3, rad9 transcript. B, detection of rad9 and hus1, transcripts in wild type and in hus137 mutant ovaries. 1, wild type ovaries; 2, hus137 mutant ovaries.

hus137 mutant flies are sensitive to HU and MMS but not to X-rays

To examine a possible requirement for hus1 in somatic checkpoints in Drosophila, the sensitivity of hus137 mutants to varying concentrations of HU and MMS and to X-ray irradiation (2500 Rads) was determined. HU stalls replication through inhibition of deoxynucleotide synthesis, MMS causes non-bulky adducts, which if not repaired by nucleotide excision repair or DNA base excision repair, result in DSB formation during replication, while X-rays cause a wide spectrum of DNA damage, including DSBs, throughout the cell cycle. Mutagen sensitivity is indicated by a decrease in the percentage of surviving homozygous flies in the irradiated cross relative to unirradiated controls. We found that homozygous hus1 flies were sensitive to MMS and HU, (Table 1 and 2). Exposure to 10 or 20 mM HU affected the survival of hus1 mutants, whereas treatment with 30 mM HU eliminated most of the hus1 homozygous class of progeny, indicating that hus1 mutant larvae are indeed highly sensitive to HU, presumably reflecting a requirement for hus1 activity in a fully functional DNA replication checkpoint. Similar results were also obtained when the hus1 allele was tested over a Deficiency (Table 1). Interestingly, we found that hus1 mutants were highly sensitive to MMS. Relatively low doses of MMS (0.025%) caused almost 100% death of hus1 mutant flies. Similar results were also obtained when testing the hus1 mutation over a Deficiency (Table 2). Most of the hus1 homozygous individuals died as larvae. When hus1 homozygous first and early second instar larvae were separated from their heterozygous siblings before MMS treatment using a GFP balancer chromosome, we found that only 19% (29/150) survived to pupal stages, whereas 75% of their heterozygous siblings (112/150) formed pupae. For both genotypes around 20% died as pharate adults.

Table 1.

HU sensitivity of hus1 mutant larvae

| hus137/TM6B in % of total |

hus137/ hus137 in % of total |

Standard deviation between experiments |

n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | 65 | 35 | 4 | 438 |

| HU 10 mM | 80 | 20 | 2 | 221 |

| HU 20 mM | 88 | 12 | 6 | 213 |

| HU 30 mM | 99 | 1 | 1 | 65 |

| hus137/TM3 Df(hus1)/TM6 (%) |

hus137/ Df(hus1) (%) |

Standard deviation between experiments |

n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 33 36 |

31 | NA | 128 |

| HU 20 mM | 43 40 |

17 | NA | 120 |

In the first set of experiments the larvae were derived from a cross between heterozygous hus137/TM6B parents; in the second experiment (last two lines) the larvae were derived from a cross of hus137/TM6B × Df(3R)110/TM3, Sb.

NA - not applicable.

Table 2.

MMS sensitivity of hus1 mutant larvae

| hus137/TM6B (%) |

hus137/ hus137 (%) | Standard deviation between experiments |

n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 47 | 53 | 4 | 771 |

| MMS 0.025% | 97 | 3 | 2 | 362 |

| MMS 0.05% | 98 | 2 | 6 | 192 |

| MMS 0.08% | 100 | 0 | 1 | 121 |

| hus137/TM3 Df(hus1)/TM6 (%) |

hus137/ Df(hus1) (%) |

Standard deviation between experiments |

n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 32 31 |

36 | NA | 358 |

| MMS 0.08% | 52 46 |

2 | NA | 246 |

In the first set of experiments the larvae were derived from a cross between heterozygous hus137/TM6B parents; in the second experiment (last two lines) the larvae were derived from a cross of hus137/TM6B × Df(3R)110/TM3, Sb.

% are given as the fraction of total surviving adults.

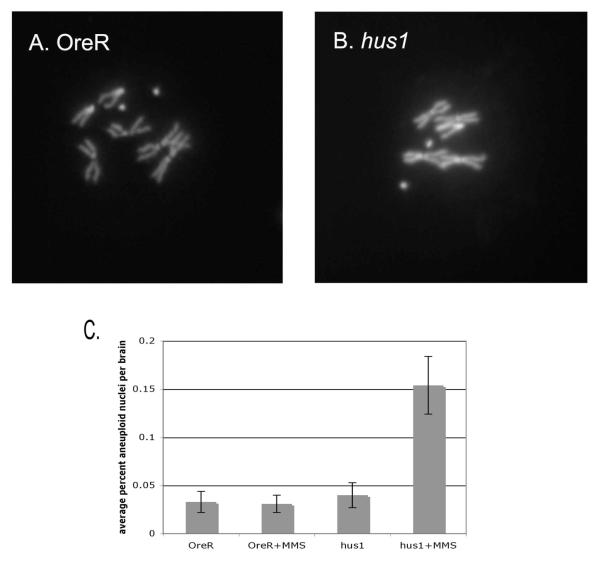

To determine potential causes of lethality after genotoxic stress, neuroblast squashes of MMS-treated larva were examined for chromosomal defects. hus1 mutant larva treated with 0.025% MMS had 15.4% aneuploid nuclei (Fig. 3B), an approximately four fold increase as compared to wild-type larva or their untreated siblings (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

hus1 mutant larva accumulates aneuploid nuclei after MMS treatment. A, wild-type neuroblast chromosome spread. B, hus137 mutant nucleus lacking one sex chromosome. C. Frequencies of aneuploid nuclei after MMS treatment. Standard deviations represent deviation between the average percent aneuploid nuclei from four brains from two separate experiments.

Treatment of hus137 with 2500 Rads of irradiation did not result in a decrease of homozygous flies relative to untreated controls. Similar results were also observed when we tested hus137/Deficiency (Table 3). In our irradiation assay we were able to detect a significant sensitivity for spnB mutant flies (Table 4), which have been shown to be only moderately sensitive to irradiation (Staeva-Viera et al., 2004), indicating that hus1 mutant flies are not sensitive to irradiation.

Table 3.

Irradiation sensitivity of hus1 mutant larvae.

| hus13/TM3 (%) |

hus137/ hus137 (%) |

Standard deviation between days |

n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | 65 | 35 | 9 | 2119 |

| IR 2500 rads | 60 | 40 | 10 | 1869 |

| hus137/TM3 Df(hus1)/TM6 (%) |

hus137/ Df(hus1) (%) |

Standard deviation between days |

n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 33 33 |

34 | 6 | 1830 |

| IR 2500 rads | 37 25 |

38 | 5 | 674 |

In the first set of experiments the larvae were derived from a cross between heterozygous hus137/TM6B parents; in the second experiment (last two lines) the larvae were derived from a cross of hus137/TM6B × Df(3R)110/TM3, Sb. % are given as the fraction of total surviving adults. Standard deviation shown is for percent hus137/Df(hus1) surviving flies.

Table 4.

Irradiation sensitivity of spn-B mutant larvae.

| spnBBU/TM6B (%) |

spnBBU/ spnBBU (%) |

Standard deviation between days |

n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | 65 | 35 | 4 | 2355 |

| IR 2500 rads | 81 | 19 | 5 | 827 |

Larvae were derived from a cross between heterozygous spnBBU/TM6B parents.

% are given as the fraction of total surviving adults

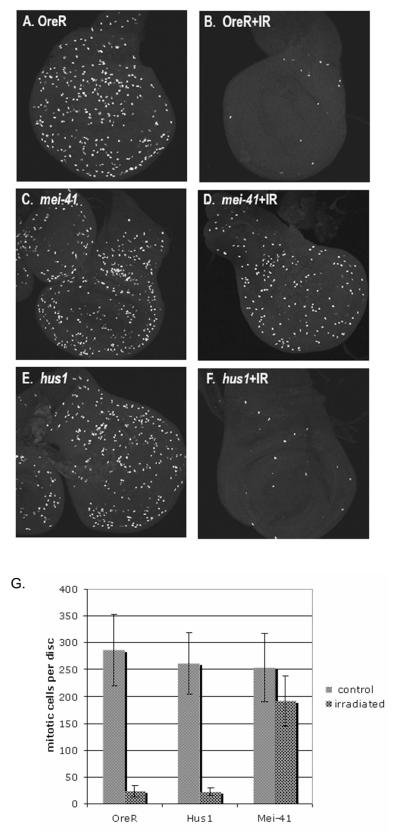

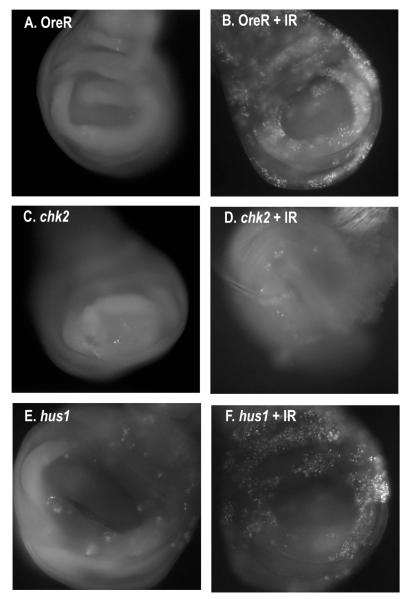

Hus1 is not required for the G2/M checkpoint and for post-irradiation induction of apoptosis

Following irradiation, a checkpoint is activated in the imaginal discs that results in a cell cycle arrest and the induction of apoptosis (Brodsky et al., 2000). Though hus1 is not required for survival after irradiation, Jaklevic and Su (2004) have suggested that while DNA repair is essential for surviving irradiation, proper cell cycle regulation and p53-dependent cell death is not essential for survival. While grapes (chk1)is required for cell cycle arrest in the imaginal discs after irradiation and p53 is required for radiation-induced death, neither mutant exhibits a significant decrease in survivorship after irradiation (Jaklevic and Su, 2004). Therefore we tested for a requirement for hus1 in cell cycle arrest after irradiation by examining the phospho-histone H3 levels 1 hour post-irradiation. Similar to wild-type controls, very few mitotic cells are observed in hus1 mutant discs after irradiation (Fig. 4), indicating that cell cycle arrest is still correctly initiated. hus1 is also not required for the post-irradiation induction of apoptosis seen in wild-type discs. Four hours after irradiation, hus1 mutant discs exhibited wild-type levels of apoptosis (Fig. 5). For comparison, we also irradiated larvae homozygous mutant for mei-41. As previously reported (Jaklevic and Su, 2004), we observed that cell division was not arrested in the mei-41 mutant. This result shows that the requirements for hus1 differ from those of mei-41 after IR.

Figure 4.

hus1 is not required for the G2/M checkpoint in the developing wing disc. Larva were mock-irradiated or irradiated with 4000 rads and allowed to recover for one hour before detection prior to fixation for (I-P) phosopho-histone H3 staining. G, Number of mitotic cells in imaginal wing discs. Standard deviations represent deviations in the average number of mitotic cells from at least five wing discs.

Figure 5.

hus1 is not required for post-irradiation induction of apoptosis in the developing wing disc. Larva were mock-irradiated or irradiated with 4000 Rads and allowed to recover for four hours before detection with (A-F) acridine orange. Representative discs shown. At least fifteen discs were examined for each condition.

The hus137 mutant suppresses the pattering defects caused by mutations in the DNA repair enzymes, but not the oocyte nuclear defects

Mutations in the spindle class of double-strand break (DSB) DNA repair enzymes, such as spn-A (RAD51), spn-B (XRCC3), spn-C(HEL308), spn-D (Rad51C) and okr (Dmrad54), affect dorsal-ventral patterning in Drosophila oogenesis and cause defects in the appearance of the oocyte nucleus (Ghabrial et al., 1998; Staeva-Vieira et al., 2003; Abdu et al., 2003; Laurencon et al., 2004). Interestingly, the defects in dorsal-ventral patterning and in the oocyte nucleus are dependent on the activation of a meiotic checkpoint (Ghabrial and Schüpbach, 1999; Abdu et al., 2002; Staeva-Vieira et al., 2003). Activation of the meiotic checkpoint prevents efficient translation of gurken (grk) mRNA, which results in a ventralization of eggs and embryos.

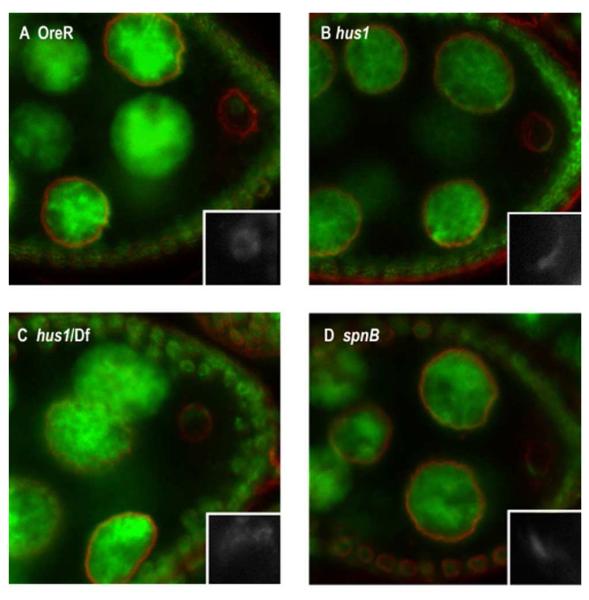

The patterning and the oocyte nuclear defects in mutants affecting double-strand DNA repair can be suppressed by blocking the formation of double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) during meiosis using mutations in the topoisomerase mei-W68 (Ghabrial and Schüpbach, 1999) or by eliminating the checkpoint by using mutations in mei-41 and chk2 (Ghabrial and Schüpbach, 1999; Abdu et al., 2002; Staeva-Vieira et al., 2003). To study whether hus1 is required in the activation of the meiotic checkpoint due to unrepaired double-strand DNA breaks, flies double mutant for hus1 and spn-B or okra were generated. In double-mutant flies we observed suppression of the dorsal-ventral pattering defects as compared to the single mutants (Table 5). However, the oocyte nuclear defects were not suppressed by our null mutation in hus1 (Table 6). Interestingly, analyzing the organization of the oocyte nucleus DNA in the hus1 single mutant revealed similar oocyte nuclear defects (Table 6) as those produced by mutations in DNA repair enzymes. In hus1 mutants the DNA within the oocyte nucleus is found in variety of conformations including the smooth spherical wild-type shape (Fig. 6A), oblong shape (Fig. 6B) or in several separate pieces along the nuclear periphery (data not shown) similar to the karyosome defects found in the spindle class of DNA repair enzyme mutations (Fig. 6D). Similar nuclear organization defects were obtained when the hus1 allele was tested over a Deficiency (Fig. 6C). To demonstrate that the karyosome defects are due to the lack of the hus1 gene, we expressed the entire hus1 open reading frame using an actin-Gal4 driver line in hus137 mutant background and found that this transgene fully rescues the karyosome defects (Data not shown).

Table 5.

Eggshell phenotypes of spn-B and okra alone and in combination with hus1.

| Maternal genotype | Wild-type-like eggshell (%) |

Abnormal eggshell (%) |

n |

|---|---|---|---|

| spn-BBU | 42 | 58 | 325 |

| hus137 spn-BBU / spn-BBU | 55 | 45 | 458 |

| hus137 spn-BBU | 99 | 1 | 652 |

| okrAA | 49 | 51 | 321 |

| okrAA/ okrAA; hus137/TM6B | 65 | 35 | 254 |

| okrAA/ okrAA; hus137/ hus137 | 99 | 1 | 677 |

Wild-type-like egg shells display 2 separate dorsal appendages. Abnormal, ventralized egg shells display partially or completely fused appendages or lack appendages altogether.

Table 6.

Karyosome phenotypes of spn-B and okra alone and in combination with hus1.

| Maternal genotype | Wild-type-like oocyte nucleus (%) |

Abnormal oocyte nucleus (%) |

n |

|---|---|---|---|

| hus137 spn-BBU / spn-BBU | 2 | 98 | 88 |

| hus137 spn-BBU | 1 | 99 | 74 |

| okrAA/ okrAA; hus137/TM6B | 4 | 96 | 65 |

| okrAA/ okrAA; hus137/ hus137 | 3 | 97 | 87 |

| hus137 | 8 | 92 | 121 |

Figure 6.

Organization of the DNA in the oocyte nucleus in wild-type and hus1 mutants. DNA in green and nucleus membrane in red. Inserts show a higher magnification of the oocyte DNA. A, wild-type egg chamber. B, hus37 egg chamber. C, hus37/Df(3R)110 egg chamber. D, spnBBU egg chamber. The wild-type karysome is a sphere near the center of the nucleus, while the mutant karysomes are crescent-shaped DNA masses near the nuclear periphery.

Discussion

In this study we analyzed the requirement of the Drosophila Hus1 protein in somatic and meiotic checkpoints. First, we analyzed the interaction of the 9-1-1 complex in a yeast two hybrid assay. We found that Hus1 interacted with Rad1 or Rad9, however no interaction between Rad1 and Rad9 was observed. The yeast two hybrid system may not be sensitive enough to pick up the interaction, since possibly the interaction between these two proteins is more transient than the interaction between Hus1 and the other proteins. Similar results were seen in C. elegans where these proteins interact in vivo (Hofmann et al., 2002).

Several studies have investigated the role of hus1 during development. In mouse, hus1 is an essential gene since inactivation of hus1 results in mid-gestational embryonic lethality due to widespread apoptosis. Also, loss of hus1 leads to an accumulation of genome damage (Weiss et al., 2000). Both fission and budding yeast that lack hus1 fail to arrest the cell cycle after DNA damage or blockage of DNA synthesis (Enoch et al., 1992; Hartwell et al., 1994; Kostrub et al., 1997). In C. elegans although hus1 is not absolutely required for embryonic survival, a significant fraction of hus1 embryos die during embryogenesis, likely due to genomic instability. Also, hus1 mutants fail to induce apoptosis and proliferation arrest following DNA damage and show increased sensitivity to DNA damage-induced lethality (Hofmann et al., 2000). We found that the Drosophila hus1 is not an essential gene, although similarly to C. elegans the females are sterile; this is probably due to the defects in the organization of the DNA within the oocyte nucleus.

In order to test for a requirement for Drosophila hus1 in response to genotoxic stress, we examined the survival rates of flies after exposure to HU, MMS, and IR during larval development and found that hus1 mutant flies were sensitive only to HU and MMS. This result suggests that hus1 is required for the activation of an S phase checkpoint. It is possible that this requirement is due to a role of hus1 in Chk1 activation after genotoxic stresses that affect S phase. In yeast and mice, hus1 has been shown to be required for Chk1 activation after replicative stress (Bao et al., 2004, Weiss et al., 2003) In Drosophila, mutations affecting grapes/Dchk1 and mei-41/ATR fail to show a decrease in BrdU-staining after irradiation, indicating a defect in an S-phase checkpoint (Jaklevic and Su, 2004), and it would therefore seem likely that Hus1 signals to activate Chk1/Grapes through Mei-41 during S phase. An increase in aneuploid nuclei in hus1 mutants after MMS treatment is consistent with a requirement for hus1 in the response to DNA damage caused during S phase as it has been suggested in budding yeast that spontaneous chromosome loss is primarily suppressed by functional S phase checkpoints and not by G2/M checkpoints (Klein, 2001). Since the hus1 mutant still exhibits cell cycle arrest after irradiation, hus1 does not seem to be required for the G2/M checkpoint that is dependent on Mei-41. Rather, our data suggest that hus1 is only required for certain DNA damage situations, and not for the same spectrum as Mei-41.

Activation of a meiotic checkpoint, also known as the pachytene checkpoint, in response to the persistence of unrepaired DSBs appears to be a conserved regulatory feature common to yeast, worms, flies and vertebrates. However, a requirement for the 9-1-1 complex in activation of the meiotic checkpoint has only been demonstrated in budding yeast. It was found that mutations in the yeast Hus1 homologue, Mec3, and the Rad1 homologue, Ddc-1, abolish the pachytene checkpoint in budding yeast (Hong and Roeder, 2000). In Drosophila, mutations in the spindle class of double-strand break (DSB) DNA repair enzymes, such as spn-A (RAD51), spn-B (XRCC3), spn-C(HEL308), spn-D (Rad51C) and okr (Dmrad54), affect dorsal-ventral patterning in Drosophila oogenesis and cause defects in the appearance of the oocyte nucleus (Ghabrial et al., 1998; Staeva-Vieira et al., 2003; Abdu et al., 2003; Laurencon et al., 2004). Interestingly, the defects in dorsal-ventral patterning and in the oocyte nucleus are dependent upon activation of a meiotic checkpoint (Ghabrial and Schüpbach, 1999; Abdu et al., 2002; Staeva-Vieira et al., 2003). We found that hus1 mutants are able to suppress the dorsal-ventral defects but not the defects in the organization of the DNA within the oocyte nucleus. The suppression of the DV patterning defects of spnB mutants demonstrates that during meiosis Hus1 is required for the meiotic checkpoint in response to persistent DSBs. This finding is interesting in light of the fact that hus1 mutants are not IR sensitive or required for somatic checkpoints after irradiation. Either there is a fundamental difference between germline and somatic DSBs and DSB response machinery, or the non-DSB lesions created during irradiation that are not present during meiotic recombination serve as triggers for an alternative sensing mechanism that does not require hus1and is therefore still able to activate a checkpoint mechanism. The inability of hus1 mutants to suppress the karyosome phenotype along with the hus1 mutant phenotype by itself, demonstrates that hus1 is required for the organization of the oocyte DNA, a function that might be independent of the meiotic checkpoint.

In this study we have shown that Drosophila Hus1 is required for both the meiotic and somatic DNA damage responses as well as demonstrating a novel role of Hus1 in the organization of the oocyte nuclear DNA. While some of the functions of Hus1, such as binding to 9-1-1 complex members and an essential role in survival to genotoxic stress during S-phase, appear to be conserved across the species studied so far, some Hus1 functions seem to be less conserved. In contrast to the findings in plants, yeast, worms and mouse, fly Hus1 is not required for survival after irradiation. Finally, the karyosome defect of hus1 mutants demonstrates a role for Drosophila Hus1 in organizing the chromosomal DNA of the meiotic nucleus.

Acknowledgment

We thank Itai Opatovsky for help with the yeast two hybrid assays. We also thank Joe Goodhouse for help with confocal imaging and analysis, Daryl Gohl for help with the chromosome squashes and Lihi Gur Arie for the help with the transgenic flies. This work was supported by a Research Career Development Award from the Israel Cancer Research Fund to UA, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and by NIH grants PO1 CA41086 to TS, and a New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research Fellowship to MK.

References

- Abdu U, Brodsky M, Schupbach T. Activation of a meiotic checkpoint during Drosophila oogenesis regulates the translation of Gurken through Chk2/Mnk. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1645–51. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdu U, Gonzalez-Reyes A, Ghabrial A, Schupbach T. The Drosophila spn-D gene encodes a RAD51C-like protein that is required exclusively during meiosis. Genetics. 2003;165:197–204. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Lu T, Wang X, Zheng H, Wang LE, Wei Q, Hittelman WN, Li L. Disruption of the Rad9/Rad1/Hus1 (9-1-1) complex leads to checkpoint signaling and replication defects. Oncogene. 2004;23:5586–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen HJ, Levis RW, Liao G, He Y, Carlson JW, Tsang G, Evans-Holm M, Hiesinger PR, Schulze KL, Rubin GM, et al. The BDGP gene disruption project: single transposon insertions associated with 40% of Drosophila genes. Genetics. 2004;167:761–81. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez VP, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Cesare AJ, Maniwa Y, Griffith JD, Hurwitz J, Sancar A. Loading of the human 9-1-1 checkpoint complex onto DNA by the checkpoint clamp loader hRad17-replication factor C complex in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1633–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437927100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi X, Wei SC, Rong YS. Telomere protection without a telomerase; the role of ATM and Mre11 in Drosophila telomere maintenance. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1348–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky MH, Sekelsky JJ, Tsang G, Hawley RS, Rubin GM. mus304 encodes a novel DNA damage checkpoint protein required during Drosophila development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:666–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky MH, Weinert BT, Tsang G, Rong YS, McGinnis NM, Golic KG, Rio DC, Rubin GM. Drosophila melanogaster MNK/Chk2 and p53 regulate multiple DNA repair and apoptotic pathways following DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1219–31. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1219-1231.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtelow MA, Roos-Mattjus PM, Rauen M, Babendure JR, Karnitz LM. Reconstitution and molecular analysis of the hRad9-hHus1-hRad1 (9-1-1) DNA damage responsive checkpoint complex. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25903–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102946200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspari T, Dahlen M, Kanter-Smoler G, Lindsay HD, Hofmann K, Papadimitriou K, Sunnerhagen P, Carr AM. Characterization of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Hus1: a PCNA-related protein that associates with Rad1 and Rad9. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1254–62. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1254-1262.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasika GK, Lin SC, Zhao S, Sung P, Tomkinson A, Lee EY. DNA damage-induced cell cycle checkpoints and DNA strand break repair in development and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 1999;18:7883–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch T, Carr AM, Nurse P. Fission yeast genes involved in coupling mitosis to completion of DNA replication. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2035–46. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty P, Campbell SD, Abu-Shumays R, Phalle BS, Yu KR, Uy GL, Goldberg ML, Sullivan W. The Drosophila grapes gene is related to checkpoint gene chk1/rad27 and is required for late syncytial division fidelity. Curr Biol. 1997;7:418–26. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial A, Ray RP, Schupbach T. okra and spindle-B encode components of the RAD52 DNA repair pathway and affect meiosis and patterning in Drosophila oogenesis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2711–23. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner M, van Kreeveld S, Su TT. mei-41 and bub1 block mitosis at two distinct steps in response to incomplete DNA replication in Drosophila embryos. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1595–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial A, Schupbach T. Activation of a meiotic checkpoint regulates translation of Gurken during Drosophila oogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:354–7. doi: 10.1038/14046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hang H, Zhang Y, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Wang C, Lieberman HB. Identification and characterization of a paralog of human cell cycle checkpoint gene HUS1. Genomics. 2002;79:487–92. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari KL, Santerre A, Sekelsky JJ, McKim KS, Boyd JB, Hawley RS. The mei-41 gene of D. melanogaster is a structural and functional homolog of the human ataxia telangiectasia gene. Cell. 1995;82:815–21. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JC, Haber JE. Surviving the Breakup: The DNA Damage Checkpoint. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;19:210–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.051206.105231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzeberg F, Chen IP, Hartung F, Orel N, Angelis KJ, Puchta H. The Rad17 homologue of Arabidopsis is involved in the regulation of DNA damage repair and homologous recombination. Plant J. 2004;38:954–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai I, Wang HG. A role of the C-terminal region of human Rad9 (hRad9) in nuclear transport of the hRad9 checkpoint complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25722–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann ER, Milstein S, Boulton SJ, Ye M, Hofmann JJ, Stergiou L, Gartner A, Vidal M, Hengartner MO. Caenorhabditis elegans HUS1 is a DNA damage checkpoint protein required for genome stability and EGL-1-mediated apoptosis. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1908–18. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong EJ, Roeder GS. A role for Ddc1 in signaling meiotic double-strand breaks at the pachytene checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2002;16:363–76. doi: 10.1101/gad.938102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaklevic B, Su TT. Relative contribution of DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoints, and cell death to survival after DNA damage in Drosophila larvae. Curr Biol. 2004;14:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein HL. Spontaneous chromosome loss in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is suppressed by DNA damage checkpoint functions. Genetics. 2001;159:1501–09. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.4.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrub CF, Knudsen K, Subramani S, Enoch T. Hus1p, a conserved fission yeast checkpoint protein, interacts with Rad1p and is phosphorylated in response to DNA damage. EMBO J. 1998;17:2055–66. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurencon A, Orme CM, Peters HK, Boulton CL, Vladar EK, Langley SA, Bakis EP, Harris DT, Harris NJ, Wayson SM, et al. A large-scale screen for mutagen-sensitive loci in Drosophila. Genetics. 2004;167:217–31. doi: 10.1534/genetics.167.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masrouha N, Yang L, Hijal S, Larochelle S, Suter B. The Drosophila chk2 gene loki is essential for embryonic DNA double-strand-break checkpoints induced in S phase or G2. Genetics. 2003;163:973–82. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.3.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKim KS, Jang JK, Sekelsky JJ, Laurencon A, Hawley RS. mei-41 is required for precocious anaphase in Drosophila females. Chromosoma. 2000;109:44–9. doi: 10.1007/s004120050411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikemus SR, McGinnis N, Queiroz-Machado J, Tukachinsky H, Takada S, Sunkel CE, Brodsky MH. Drosophila atm/telomere fusion is required for telomeric localization of HP1 and telomere position effect. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1850–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.1202504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrilla-Castellar ER, Alander SJ, Karnitz L. Dial 9-1-1 for DNA damage: the Rad9-Hus1-Rad1 (9-1-1) clamp complex. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1009–14. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M, DeLuca C, Hirao A, Stambolic V, Potter J, Zhou L, Liepa J, Snow B, Arya S, Wong J, et al. Chk2 regulates irradiation-induced, p53-mediated apoptosis in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11305–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172382899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauen M, Burtelow MA, Dufault VM, Karnitz LM. The human checkpoint protein hRad17 interacts with the PCNA-like proteins hRad1, hHus1, and hRad9. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29767–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibon OC, Laurencon A, Hawley R, Theurkauf WE. The Drosophila ATM homologue Mei-41 has an essential checkpoint function at the midblastula transition. Curr Biol. 1999;9:302–12. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibon OC, Stevenson VA, Theurkauf WE. DNA-replication checkpoint control at the Drosophila midblastula transition. Nature. 1997;388:93–7. doi: 10.1038/40439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva E, Tiong S, Pedersen M, Homola E, Royou A, Fasulo B, Siriaco G, Campbell SD. ATM is required for telomere maintenance and chromosome stability during Drosophila development. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P, Morata G. Differential mitotic rates and patterns of growth in compartments in the Drosophila wing. Dev Biol. 1981;85:299–308. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song YH, Mirey G, Betson M, Haber DA, Settleman J. The Drosophila ATM ortholog, dATM, mediates the response to ionizing radiation and to spontaneous DNA damage during development. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling AC, Rubin GM. Transposition of cloned P elements into Drosophila germ line chromosomes. Science. 1982;218:341–7. doi: 10.1126/science.6289435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staeva-Vieira E, Yoo S, Lehmann R. An essential role of DmRad51/SpnA in DNA repair and meiotic checkpoint control. Embo J. 2003;22:5863–5874. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada S, Kelkar A, Theurkauf WE. Drosophila checkpoint kinase 2 couples centrosome function and spindle assembly to genomic integrity. Cell. 2003;113:87–99. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doren M, Williamson AL, Lehmann R. Regulation of zygotic gene expression in Drosophila primordial germ cells. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:243–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venclovas C, Thelen MP. Structure-based predictions of Rad1, Rad9, Hus1 and Rad17 participation in sliding clamp and clamp-loading complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2481–93. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.13.2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert T. DNA damage and checkpoint pathways: molecular anatomy and interactions with repair. Cell. 1998;94:555–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS, Enoch T, Leder P. Inactivation of mouse Hus1 results in genomic instability and impaired responses to genotoxic stress. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1886–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS, Leder P, Vaziri C. Critical role for mouse Hus1 in an S-phase DNA damage cell cycle checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:791–803. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.791-803.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Du W. Drosophila chk2 plays an important role in a mitotic checkpoint in syncytial embryos. FEBS Lett. 2003;545:209–12. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Xin S, Du W. Drosophila Chk2 is required for DNA damage-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:394–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408:433–9. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]