Abstract

Ribose-5-phosphate isomerases (EC 5.3.1.6) interconvert ribose 5-phosphate and ribulose 5-phosphate. This reaction permits the synthesis of ribose from other sugars, as well as the recycling of sugars from nucleotide breakdown. Two unrelated types of enzyme can catalyze the reaction. The most common, RpiA, is present in almost all organisms (including Escherichia coli), and is highly conserved. The second type, RpiB, is present in some bacterial and eukaryotic species and is well conserved. In E. coli, RpiB is sometimes referred to as AlsB, because it can take part in the metabolism of the rare sugar, allose, as well as the much more common ribose sugars. We report here the structure of RpiB/AlsB from E. coli, solved by multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) phasing, and refined to 2.2 Å resolution. RpiB is the first structure to be solved from pfam02502 (the RpiB/LacAB family). It exhibits a Rossmann-type αβα-sandwich fold that is common to many nucleotide-binding proteins, as well as other proteins with different functions. This structure is quite distinct from that of the previously solved RpiA; although both are, to some extent, based on the Rossmann fold, their tertiary and quaternary structures are very different. The four molecules in the RpiB asymmetric unit represent a dimer of dimers. Active-site residues were identified at the interface between the subunits, such that each active site has contributions from both subunits. Kinetic studies indicate that RpiB is nearly as efficient as RpiA, despite its completely different catalytic machinery. The sequence and structural results further suggest that the two homologous components of LacAB (galactose-6-phosphate isomerase) will compose a bi-functional enzyme; the second activity is unknown.

Keywords: ribose-5-phosphate isomerase, pentose phosphate pathway, galactose-6-phosphate isomerase, MAD, X-ray crystallography

Introduction

Ribose-5-phosphate isomerases (EC 5.3.1.6) catalyze the inter-conversion of ribose 5-phosphate and ribulose 5-phosphate (Figure 1). This activity is essential to the pentose phosphate pathway, and to the Calvin cycle of plants. As for most isomerizations, the reaction is near equilibrium, and can run in either direction depending on the relative substrate and product concentrations. When ribose 5-phosphate is abundant, the reaction runs in the “forward” direction as part of the non-oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway. In this way, the phospho-sugar is converted into intermediates for glycolysis, as well as precursors for the synthesis of amino acids, vitamins, nucleotides and cell-wall constituents. Running “in reverse”, the isomerization is the final step in the transformation of glucose 6-phosphate into the ribose 5-phosphate needed for synthesis of nucleotides and cofactors; the previous steps, which comprise the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway, are a major source of the NADPH required for reductive biosynthesis.

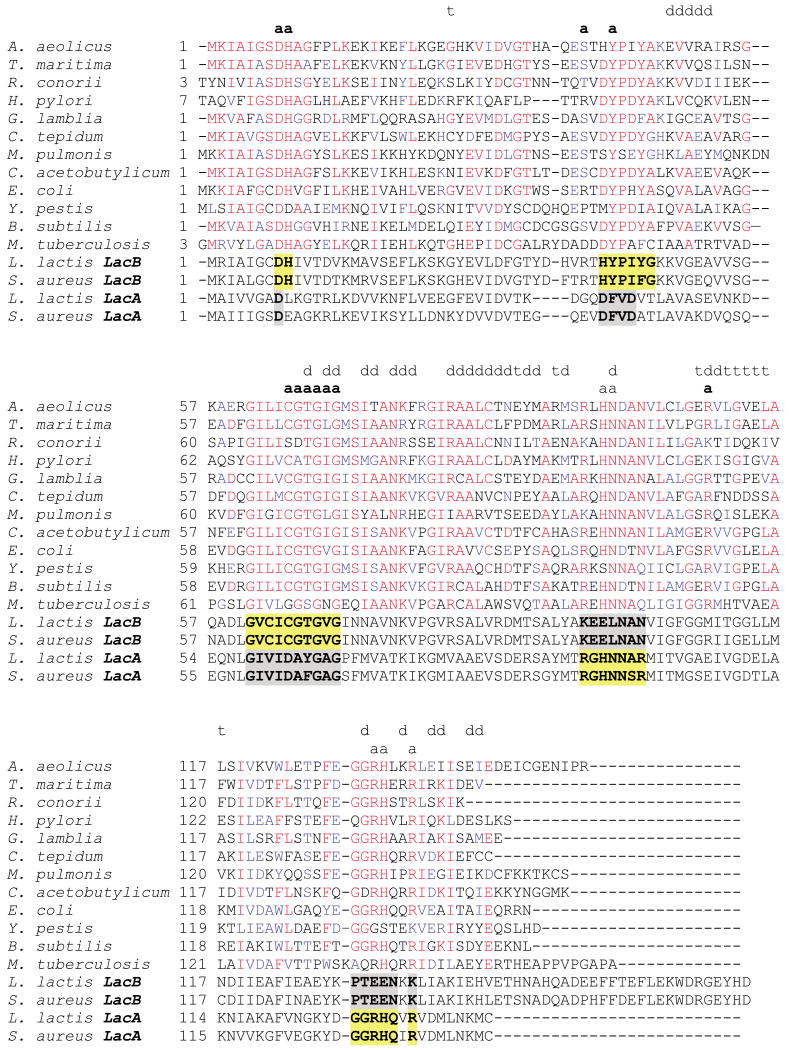

Figure 1.

Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase reaction. The expected catalytic acid and base are placed with respect to the substrates, products and intermediates; carbon atoms of the sugars are numbered. In the first step with ribose 5-phosphate as substrate, acid–base catalysis provided by either solvent or the enzyme opens the five-membered furanose ring to give the open-chain aldose. A basic group of the enzyme must then extract a proton from C2 of the aldose, generating a cis-1,2-enediol(ate) intermediate, and release the same proton at C1. A second protein group located on the opposite site of the active site transfers a proton from O2 to O1, to produce the ketose sugar.

Two completely unrelated enzymes are able to catalyze this vital reaction. Both are sometimes found in the same organism, as is the case for Escherichia coli.1,2 E. coli RpiA is a 23 kDa constitutively expressed enzyme,2 whereas synthesis of the smaller (17 kDa) RpiB lies under the control of a repressor.3 A double mutant (rpiA−rpiB−) showed severely impaired growth under any conditions, demonstrating that the reaction is essential.3 Most E. coli strains defective in the RpiA gene are ribose auxotrophs; synthesis of RpiB is induced partially when ribose is available, and it is then able to act alone in the isomerization.4 Mutants of RpiB have no phenotype under most conditions, presumably because RpiA is sufficient for ribose metabolism. More recent studies have shown that the gene for E. coli RpiB lies immediately adjacent to an operon that is apparently devoted to the acquisition and metabolism of the rare sugar allose; this sugar is more effective than ribose as an inducer of RpiB synthesis in E. coli.5,6 It has, therefore, been proposed that this enzyme should be now referred to as AlsB. As a role for other members of the RpiB family in allose metabolism has not been established, we will use the traditional designation, RpiB.

RpiAs are distributed very broadly, and have now been identified in more than 100 species. By contrast, RpiB-like enzymes (∼70 found at the time of writing) are almost exclusively restricted to bacteria, with a very few examples emerging in unicellular eukaryotes. A number of bacteria (about one-third in the 77 completely sequenced genomes inspected) possess only RpiB, while another group (about one-sixth, including E. coli) appears to have both RpiA and RpiB.

RpiA and RpiB are both dimers with Km values of the order of 1 mM. The enzymes apparently differ in their catalytic mechanisms; RpiB, but not RpiA, is sensitive to iodoacetate, which modifies sulfhydryl groups. The three-dimensional structure of RpiA from Pyrococcus horikoshii7 and E. coli8,9 provided insights into its mode of action. Here, we report the 2.2 Å resolution apo structure of RpiB (AlsB) from E. coli, and a kinetic description of the enzyme. These studies have allowed us to locate the RpiB active site, and to identify the determinants of substrate binding and activity.

Results

Protein expression, purification, activity

E. coli RpiB was over-expressed as a His-tagged Se-Met-labeled protein for the structural work reported here. A different His-tag construct was used in most of the kinetic studies. In neither case was cleavage of the tag necessary for experimental work.

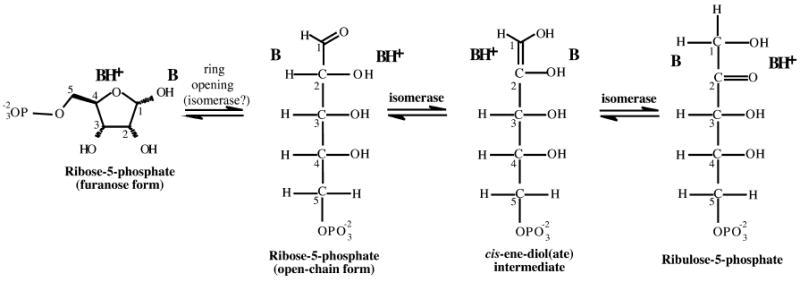

The kinetic properties of the final enzyme preparations were tested using a spectrophotometric assay that follows the conversion of ribose 5-phosphate to ribulose 5-phosphate. A typical set of kinetic experiments is shown in Figure 2; the results did not differ significantly for the two constructs. Hanes plots indicated that Km is 1.23 mM and kcat is 69 s−1 for the ribose 5-phosphate substrate.

Figure 2.

Enzymatic characterization. Data from a typical series of kinetic experiments using the second construct are shown, together with the curve calculated from the Michaelis–Menten equation using the overall average kcat of 69 s−1 and Km of 1.23 mM (enzyme concentration 30 nM). The inset presents the same data in a Hanes–Woolf plot; the line calculated with the average kinetic constants is shown here in gray.

No effective reversible inhibitor of RpiB has been reported. Arabinose 5-phosphate (a good competitive inhibitor of RpiA: Ki 2.1 mM9) was investigated here, and shown to have a Ki of ≥10 mM. Phospho(enol)pyruvate, also inhibited with a Ki of ∼10 mM. Fructose 6-phosphate inhibits slightly, with a Ki of ∼50 mM. Ribose was a very poor substrate rather than an inhibitor.

MgCl2 and KCl were tested at concentrations of 10 mM and 100 mM, respectively, but had no effect on activity.

Crystallization, data collection, structure solution and refinement

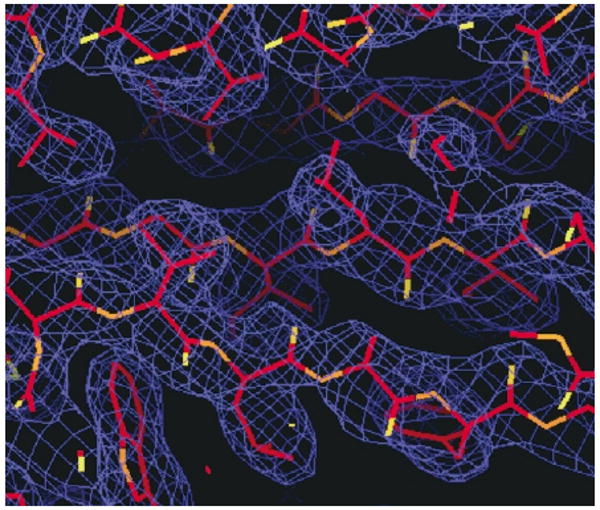

The 2.2 Å structure of apo RpiB was determined using multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) data from a single crystal of Se-Met-substituted enzyme. Statistics relating to the quality of the X-ray diffraction data are summarised in Table 1, and a representative sample of electron density in the original MAD map is shown in Figure 3. There are four 149 residue chains in the asymmetric unit; the final model includes residues 1–147 for subunits A and C, and 1–146 for subunits B and D. Either 12 or 13 residues of each N-terminal expression tag were also clearly visible in the electron density. Statistics related to the final refined protein model are given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Data collection statistics

| Peak | Inflection | Remote | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9777 | 0.9779 | 0.95374 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| No. reflections measured | 265,246 | 206,493 | 206,191 |

| No. unique reflections | 38,823 | 30,133 | 30,071 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.0 | 97.9 | 97.7 |

| Rmergea (overall) | 8.9 | 8.1 | 7.8 |

| 〈I〉/<σ(I) > | 18.9 | 19.1 | 18.6 |

| Phasing powerb to 2.4 Å | 2.4 | 2.2 | 0.7 |

| FOMMADc | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.15 |

| FOMMAD (overall) | – | 0.55 | – |

| FOM (sf)d | – | 0.88 | – |

The Se-Met enzyme crystallized in space group I41 with unit cell dimensions a = 145.588 Å, b = 145.588 Å and c = 74.784 Å.

Rmerge = Σ|Ii − Im|/ΣIi, where Ii is the intensity of the measured reflection i and Im is the mean intensity of all symmetry-related reflections.

Phasing power = FH/ERMS. FP, FPH and FH are the protein, derivative and heavy-atom structure factors, respectively, and ERMS is the residual lack of closure.

Figure of merit from MAD phasing.

Figure of merit after solvent flipping.

Figure 3.

Electron density. Representative section of electron density in the original MAD map calculated at 2.4 Å resolution (contoured at 1σ), shown together with the structure of the final refined model.

Table 2.

Structure refinement statistics

| Model | Se-Met apo |

|---|---|

| Resolution range (Å) | 36.4–2.2 (2.34–2.20) |

| No. reflections used in refinement | 69,714 |

| No. reflections used for Rfree calculation | 3432 |

| Completeness (%) | 89.6 (77.9) |

| R value (%) | 21.7 (37.3) |

| Rfree (%) | 26.3 (38.1) |

| No. non-hydrogen atoms | 4767 |

| No. solvent water molecules | 299 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | |

| Protein | 40.5 |

| Solvent atoms | 47.1 |

| r.m.s.d. from ideal | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.008 |

| Bond angle (deg.) | 1.3 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Overall structure

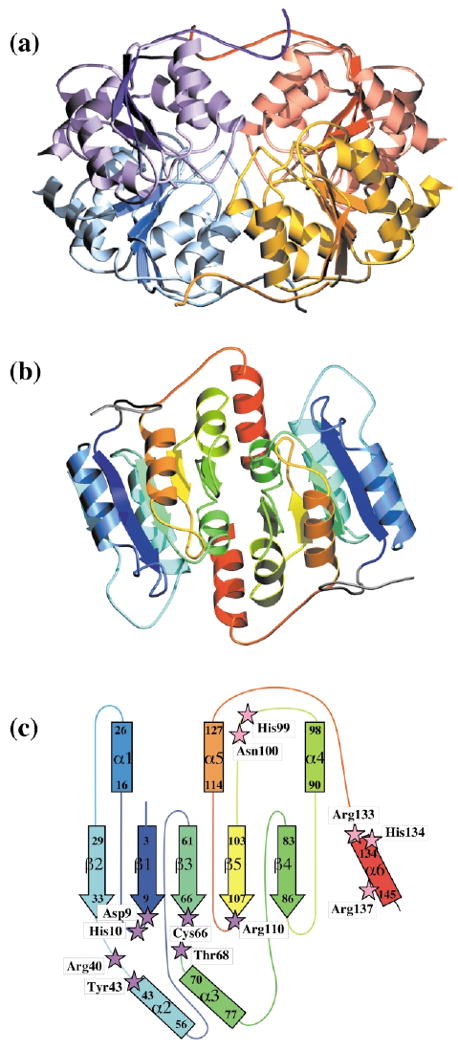

The four molecules in the RpiB asymmetric unit form a tetramer with 222 symmetry (Figure 4(a)); the subunits are identical within the limits of experimental error (r.m.s. distance 0.25–0.31 Å for the different possible pairs). Previous size-exclusion chromatography results had suggested that the enzyme is a dimer in solution,2 but dynamic light-scattering carried out as part of the current study suggested that the tetramer is indeed the dominant species. Surface accessibility calculations indicate that the tetramer in the crystal is actually a dimer of dimers. When the N-terminal tag is omitted from the calculations, the strongest contacts are found between subunits A and D (and the equivalent B and C) in the PDB entry: each molecule buries ∼1500 Å2 of its surface in those interfaces, compared to ∼300 Å2 in the A/B and A/C (and equivalent) contacts.

Figure 4.

Overall structure of RpiB. (a) The tetramer of the asymmetric unit is shown; the subunits of the A/D dimer are violet and blue, respectively, while those of the B/C dimer are orange and yellow; in all cases a darker shade indicates the central β-sheet of the subunit. (b) The AD dimer is shown, with each chain color-coded, beginning with blue at the N terminus and going through the rainbow to red at the C terminus. (c) Topology diagram of a subunit, colored in the same way as in (b). The first and last residues of secondary structural elements are indicated, along with the naming convention. Residues lining the active site are indicated as magenta stars when they originate from one subunit, and pink stars if they originate from the second of the dimer. The N-terminal His-tag is omitted in (b) and in (c).

The AD dimer is illustrated in Figure 4(b), and the secondary structure and topology of the subunit are shown with the same colouring in Figure 4(c). At the core of each subunit is a five-stranded parallel β-sheet, flanked by three helices on one face, and two on the other. The latter face has an additional helix packed onto it, which is contributed by the C terminus of the other subunit in the dimer. The core structure represents the αβα sandwich fold common to a large number of proteins, including many that bind nucleotides.10 This structural relationship had not been detected using the sequence alone in homology searches.

In the A/D and B/C dimers, five segments of each subunit contribute to the dimer interface: residues 40–44 (β2/α2 loop and beginning of α2), 68–95 (α3, β4 and α4, as well as the loops connecting them), 100 (α4/β5 loop), 110–111 (β5/α5 loop) and 133–144 (α5/α6 loop and α6). The size of this interface (1470 Å2 buried per subunit) is near the average observed for homodimers (1700(±1100) Å2)11 and accounts for 20% of the accessible surface of each subunit. The surfaces show good complementarity, with a gap volume index (2.6) that is well within the range expected for homodimers (2.2 ± 0.9).11 Approximately 65% of the atoms providing these contacts are non-polar. The polar residues of each subunit supply 11 direct hydrogen bonds, as well as other indirect interactions through six bridging water molecules.

Two segments of each subunit make additional interactions with each of the molecules in the second dimer, so producing the tetramer. Residues 89–94 (β4/α4 loop and α4) and 115–119 (α5) of the A molecule interact with the B molecule to bury a total of 350 Å2 of the surface of the A molecule; 78% of the atoms involved are non-polar. Similarly, the A molecule contributes residues 18 (α1) and 109–116 (β5/α5 loop) to the A/C interface (with 320 Å2 of the surface of the A molecule buried as a result). Of these atoms, 58% are non-polar; the polar atoms provide four direct hydrogen bonds, and make other interactions via three bridging water molecules. A total of 1300 Å2 is thus buried in these dimer–dimer contacts.

Comparison to sequence and structural homologues

The RpiB structure is the first available for a member of pfam02502/COG0698.12 This almost exclusively bacterial family of proteins includes other putative RpiBs, as well as both subunits of galactose-6-phosphate isomerase (LacA and LacB). The few eukaryotic examples of RpiB include proteins in the protozoans Giardia lamblia and Trypanosoma brucei. RpiB-like domains have been found in some plant and fungal proteins, joined to a second domain of unknown function. The plant proteins are associated with DNA damage repair/toleration in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa, a description that seems most consistent with a role in ribose metabolism.13 LacAB is a heteromultimeric enzyme that catalyses the conversion of d-galactose 6-phosphate to d-tagatose 6-phosphate in lactose and galactose catabolism.14,15 LacABs are apparently not widespread, having been identified via their biochemical function in only Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus to date. The reaction is again an aldose-ketose isomerization, i.e. it is the equivalent of the RpiB conversion for six-carbon sugars.

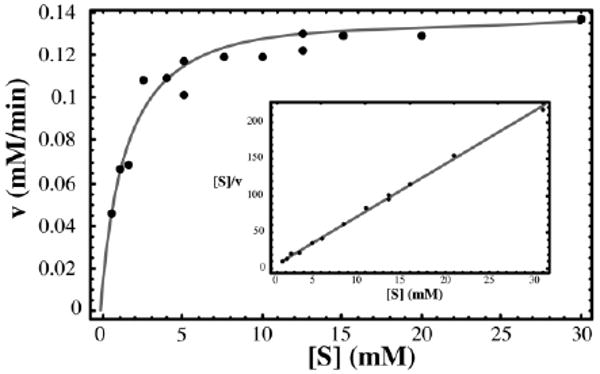

Representative sequences from the RpiB family are aligned in Figure 5. LacAs and LacBs share only about 20% amino acid sequence identity. Each, however, is more closely related to RpiB in sequence, ∼30% and 35% identity, respectively. Indeed, it seems likely that some enzymes in GenBank annotated as RpiBs may actually represent LacA or LacB, and vice versa. In the absence of thorough functional analysis, the safest means of differentiating between the different types of enzyme seems to lie in an analysis of residues within the active-site cavity (see below).

Figure 5.

Sequence conservation in the RpiB/LacAB family. Eleven representative sequences are aligned with that of E. coli K12 RpiB (gi:16131916), and shaded according to the degree of conservation: Yersinia pestis (gi:16123503), Bacillus subtilis (gi:16080745), Aquifex aeolicus (gi:15606395), Thermotoga maritima (gi:15643838), Rickettsia conorii (gi:15892325), Helicobacter pylori J99 (gi:15611588), Giardia lamblia ATCC 50803 (gi:29248748), Chlorobium tepidum TLS (gi:21673876), Mycoplasma pulmonis (gi:15829083), Clostridium acetobutylicum (gi:15896134) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv (gi:15609602). Residues are annotated if they lie within the RpiB active-site pocket (boldface a for one subunit, plaintext a for the second), or in the dimer (d) or tetramer (t) interfaces. In several cases where a residue is involved in both dimer and tetramer contacts, only the dimer interaction is indicated. Four additional sequences represent proteins with documented LacA and LacB function: Lactococcus lactis lacB (gi:149407); Staphylococcus aureus LacB (gi:21283849); L. lactis LacA (gi:149406); S. aureus LacA (gi:21283850). Residues in the active-site pocket that are conserved within these subfamilies are highlighted as follows: those that are similar to RpiB in sequence are shown in yellow, and those that suggest a different function are shown in gray.

The Protein Data Bank (PDB16) was searched for similar structures using the DALI server.17 With the RpiB subunit as a probe, the best matches were for lumazine synthase (PDB entry 1DI018) and methionine synthase (1BMT19), with Z-scores of 6.9 and 6.8, respectively (r.m.s. distances 2.8 Å and 4.0 Å). In each case, 102 residues could be aligned with 15% amino acid sequence identity. Further down the list were N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide mutase (PurE; 1QCZ20) and glutamate racemase (1B7421), with Z-scores of 6.3 and 6.0 (r.m.s. distances 3.6 Å and 3.2 Å). Other hits were found among the type 1 periplasmic binding proteins, as well as repressors and response-regulator proteins. These results confirm the relationships with Rossmann-fold proteins, but provide no real insights into RpiB action; the chemistry to be performed is not represented in any of the related proteins (despite a strong functional link to isomerization), and active-site residues are not conserved. DALI did not provide any additional insights when the dimer was used as a probe.

These searches did not reveal sequence similarity or structural homology to RpiA, the functional homologue of RpiB.

Active-site pocket

Our biochemical assays (Figure 2) showed that recombinant RpiB is nearly as efficient as RpiA9 in the conversion of ribose 5-phosphate to ribulose 5-phosphate. However, it is clear that the two enzymes are fundamentally different. Arabinose 5-phosphate, a good competitive inhibitor of RpiA, is rather poor inhibitor of RpiB (Ki of ≥10 mM). Iodoacetate irreversibly inhibits RpiB but not RpiA.2 The two structures are very different, and inspection of RpiB showed that the constellation of residues that forms the active site of RpiA is not found on the RpiB surface.

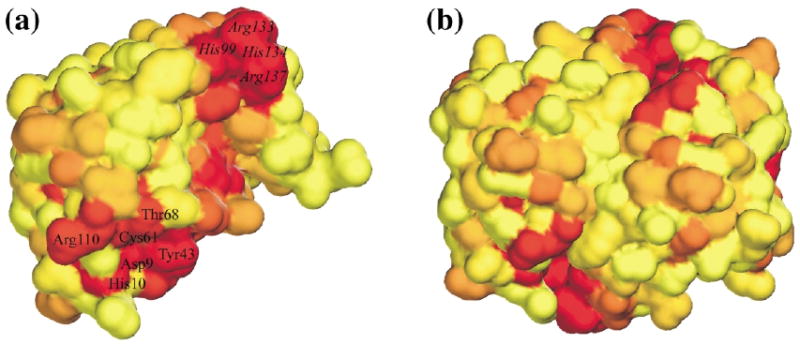

As no mutation has been reported that affects activity of any member of the RpiB/LacAB family, and no good inhibitor has been found, a combination of sequence and structural data was used to locate the active site. Sequence conservation within the RpiB subfamily (Figure 5) is mapped onto the molecular surfaces of both a single subunit and a dimer in Figure 6(a) and (b). This analysis clearly identifies a deep pocket lined with conserved residues at the subunit interface. A dimer thus contains two independent active sites, each including residues from both subunits. The putative active site represents by far the largest concentration of conserved residues on the molecular surface. Other conserved residues represent interactions in the dimer interface, e.g. Lys78 (which may be replaced by Arg) forms hydrogen bonds with the main-chain carbonyl oxygen atoms of residues 77, 79 and 82 of the opposing subunit. Residues in the dimer contacts are more conserved than the rest of the surface, while residues in tetramer contacts are not (Figure 5). The structure and sequence conservation, therefore, indicate a clear role for the dimer in RpiB function, while none for the tetramer has been established.

Figure 6.

Conservation of the molecular surfaces. (a) The surface of a subunit showing sequence conservation (based on the RpiB alignments shown in Figure 5), color-coded going from yellow (least conserved) to red (most conserved). The residues of the two halves of the putative active site are labeled. (b) The dimer surface color-coded in the same way.

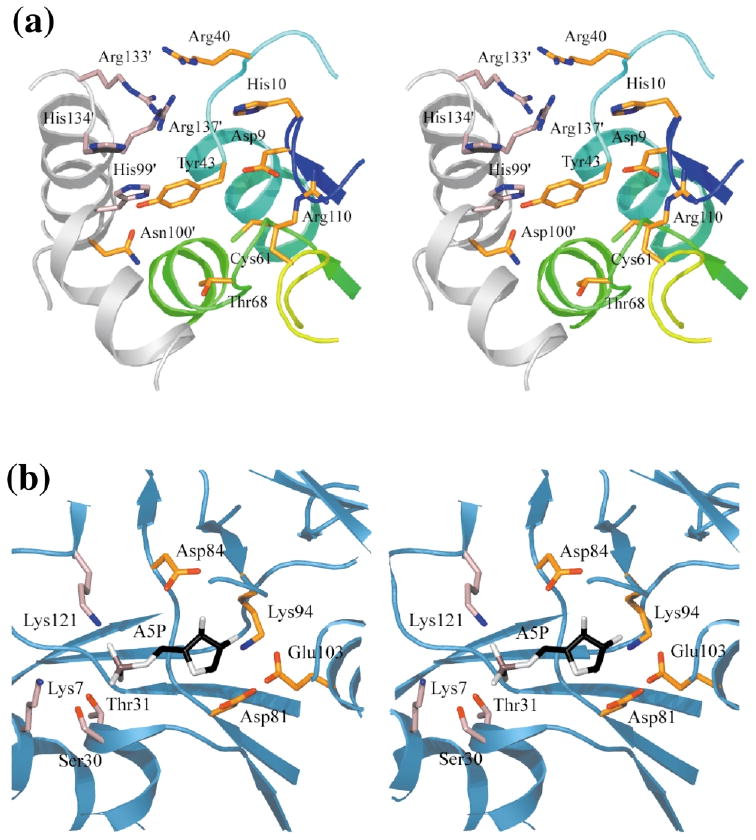

As is characteristic for α/β enzymes with a parallel sheet (including PurE and RpiA), the presumed active site of RpiB lies at the C-terminal end of the β-strands. Substrates and/or coenzymes always bind in a roughly equivalent position in such structures, although their chemical nature, as well as the function of the protein, varies widely. The active-site pocket is accessible to solvent in both dimer and tetramer. As illustrated in Figures 5–7, some residues lining each active-site cavity are drawn from one subunit, i.e. Asp9, His10, Arg40, Tyr43, Cys66, Thr68 and Arg110. The second subunit of the dimer contributes predominantly basic residues: His99′, Asn100′, Arg133′ His134′ and Arg137′. Most of these residues are very highly conserved within the RpiB subfamily. The longest motif is the GILICGTGVGISIAANKF AGIRA sequence that stretches between residues 62 and 84 of the E. coli enzyme. This segment includes residues in or near the active site, as well as those in the A/D and B/C interfaces (e.g. Tyr43 and Asn100, which hydrogen bond across the dimer interface).

Figure 7.

Active sites of ribose-5-phosphate isomerases. (a) Close-up view of the active site of RpiB. One subunit is colored according to sequence as in Figure 4(c), the other is colored gray; residues are indicated with if they are contributed by the second subunit in the dimer. (b) The active site of RpiA bound to the inhibitor, arabinose 5-phosphate (PDB entry 1O8B; sugar shown with carbon atoms black, oxygen atoms gray, and phosphate ion salmon).

Among the proteins shown to have structural similarity, the most interesting parallel is that with PurE, a mutase in the purine biosynthetic pathway. The eight active sites of this enzyme are located at the interfaces between its eight subunits. As observed for RpiB, contributions from a C-terminal helix are important in the active site, as are those made by other residues of a second subunit. In the case of PurE, however, the active-site helix is supplied by a third subunit, rather than being encompassed within the dimer.

Discussion

RpiB represents a new member of the large and diverse family of proteins that have a Rossmann fold as an element of their structure. Like the α/β barrel that is characteristic of the triose phosphate isomerase (TIM) super-family, the flat version of the parallel α/β structure seems to evolve readily to carry out many biochemical tasks. Enzymes of core metabolism are very frequently based on one of these two ancestral templates, which presumably diverged very early to serve different functions. Placement of the active sites at inter-subunit interfaces is also a recurring theme in the evolution of proteins, allowing new and useful combinations that are not possible for one subunit in isolation.

Our studies of RpiB have answered many questions about its function. The enzyme's activity is not influenced by two major biochemical ions, magnesium and potassium. This lack of ion-dependence indicates that it will not act via a hydride transfer mechanism22 like that used by d-xylose isomerase.23 Instead, RpiB is expected to utilize a cis-enediol(ate) intermediate mechanism with general acid and base catalysis, analogous to that of its functional homologue, RpiA. The kinetic constants obtained for RpiB (Km = 1.23 mM and kcat = 69 s−1) are indeed comparable to those determined for RpiA (Km = 3.1 mM and kcat = 2100 s−1).9 RpiA and RpiB, however, have very different structures, and their active sites are quite distinct (Figure 7). In the RpiA dimer, all of the residues of a particular active site are drawn from the same subunit, while in RpiB, each active site receives contributions from two subunits. The residues available for binding and catalysis are different, and RpiB does not show the same patterns of inhibition as RpiA. Therefore, the RpiA/B case represents an example of independent evolution of a particular catalytic function within the framework of different structural scaffolds.

Isomerization of ribose requires the open-chain form of the sugar, which is normally in equilibrium with the α and β-furanoses (Figure 1). The three species interconvert freely in solution via both acid and base-catalyzed mechanisms. The open-chain form is, however, much less common than the ring forms (0.1% for the free aldehyde, as compared to 64% for the β- and 36% for the α-furanose form, respectively).24 If this is taken into account, the true Km of RpiA would assume an unusually small value (3 μM, instead of 3 mM), and its kcat/Km ratio (6.8 × 108 M−1 s−1) would be very large. Based on this and other data, Jung et al.25 proposed that RpiA would first bind to a furanose sugar, and catalyze its opening prior to isomerization. The structure of RpiA and a substrate-like inhibitor (arabinose 5-phosphate) indeed showed a β-furanose ring was bound, and suggested a viable mechanism for ring opening, supporting the theory that RpiA is active in this step.9 The kcat/Km ratio of RpiB, however, is smaller (5.6 × 107 M−1 s−1), and the present structural data do not allow us to establish whether it, too, catalyzes the first step of the reaction.

Without the structure of an inhibitor complex, assignment of functional roles to each residue in the active site must be, for the most part, speculative. Conserved residues that could act in acid-base catalysis include Asp9, His10 and Cys66, all of which reside on the same subunit. Asp9 is the only one of these that is conserved in all of the available sequences. One possibility is that Asp9 and His10 (the latter changed to aspartate in some sequences) of RpiB act as the catalytic base and acid–base in the isomerization step in a manner analogous to that of the Glu165 and His95 pair in TIM.26 The distance between the critical atoms in these residues of RpiB is 3.9 Å, similar to the distance between their counterparts in TIM (3.5–4.0 Å) and RpiA (∼3.5 Å). The earlier observation that E. coli RpiB is inhibited by iodoacetate2 is explained easily by modification of Cys66, which is in the immediate vicinity. Cys66 itself is also a candidate for the catalytic base, acting in concert with Asp9. This pair of residues is conserved in the two protozoan homologues. However, Cys66 is not conserved in some other members of the family (Figure 5), which could indicate that these enzymes have found an alternative mode of action. Among the other conserved residues, Tyr43, Thr68 and Asn100 appear to be poor candidates for the general acid, and are more likely to be involved in binding rather than in catalysis.

Like TIM, RpiB also needs a way to stabilize the negatively charged intermediate of the isomerization step (the ene-diolate of Figure 1). Calculations have suggested that this is in fact the most important factor in catalysis for this class of enzyme reaction.27 Arg137 is an obvious candidate for such a role, analogous to Lys13 of TIM. While the side-chain of Arg110 is not positioned ideally in the present apo structure, its location is such that it could swing into place to assume that task during the reaction. Residues at the N-terminal end of α3 as well as those of the β3/α3 loop also appear interesting in this context; they could stabilize the enolate intermediate through hydrogen bonding.

At the other end of the active-site pocket, a remarkable cluster of positively charged side-chains provides an excellent environment for binding a phosphate group (Figure 7(a)). All of these seem to be contributed by the “second” subunit. The phosphate-binding residues need not be absolutely conserved, provided that the overall positive charge of the site is maintained, and the substrate properly positioned with respect to the catalytic components. The longer alternative substrate, allose 6-phosphate, could be accommodated by movements in these long and flexible side-chains. Obviously, the structures of complexes, as well as site-directed mutations of the active-site residues identified here, will be needed before more detailed conclusions can be reached.

Structural data suggested conformational changes occur during RpiA catalysis,9 as has been reported for many other enzymes of this type. There is no evidence that such occur in RpiB; the four molecules of the apo enzyme have essentially identical conformations in the present crystal structure. The kinetic data fit well to the Michaelis–Menten equation (Figure 2), suggesting further that allostery is not a feature of RpiB action, i.e. that the four active sites function independently.

It appears that RpiA is unique in its ribose-5-phosphate isomerase function in most organisms. The occurrence of RpiB is not universal, even among bacteria, and the metabolic and evolutionary picture is still somewhat fragmentary. It has probably persisted in some, although not all, strains of E. coli5 because it allows survival in special circumstances, such in the presence of allose. Where RpiA has been lost, RpiB presumably must take on this role alone, a task that our data show it is quite able to perform. In species that possess both types of ribose-5-phosphate isomerase, differences in their construction would have a protective role: no single class of inhibitors is likely to shut down both enzymes.

Our data also give some intriguing insights into the structure and function of the related bacterial enzyme, LacAB.14,15 This enzyme is a heteromultimer with a total molecular mass of ∼100 kDa, corresponding to approximately six subunits. It is not known how this putative hexamer is constructed, although both LacA and LacB are required for full activity. LacAB from Staphylococcus aureus is not activated by monovalent or divalent cations and is not inhibited by EDTA,28 in accord with the results described here for RpiB. Inspection of the sequences in Figure 5 shows that, while both LacA and LacB are closely related to RpiB, the potential catalytic residues described above are present in only LacB. The conserved active-site residues in the motif 62 GILICGTGVG 71 of RpiB are nearly identical with the corresponding residues of LacB, but different from the LacA sequence in this region (GIVIDAYGAG). As a result, in RpiB/LacB Cys66 and Thr68 are changed to an aspartate and tyrosine/phenylalanine residue, respectively, in LacA. Tyr43 is also replaced by phenylalanine, and Pro44 by isoleucine or valine in LacA, with likely effects on the character of the active site. In contrast, the residues that are implicated in phosphate binding are present in LacA, but not in LacB. For example, the conserved sequence 131 GGRHxxR 137 of RpiB corresponds to a typical LacA feature (GGRHQxR) that is replaced with different conserved sequence in LacB (PTEENKK). Residues of the dimer interface are rather well conserved in both instances.

Thus a homodimer of either LacA or LacB would not have the necessary components to bind and isomerize a sugar phosphate, if it follows the same scheme as RpiB. Instead, we propose that the basic unit of LacAB will be a heterodimer, with two different types of active site. One of these (indicated by the green highlighting in Figure 5) could easily account for the observed galactose-6-phosphate isomerase activity. The equivalents of Asp9, His10, Tyr43, Cys66, Thr68 and surrounding residues in this half-site would all be contributed by LacB. The other half of this active site, which is likely to function in phosphate binding, would be contributed by LacA. The second type of active site (highlighted in gray in Figure 5) in this heterodimer would have a very different character. The equivalent of Asp9 is present, but the counterparts of His10 and Cys66 are not; the latter is replaced by an aspartic acid residue, which could act in concert with the aspartate residue at position 9. In the other half of this site, only the equivalent of Arg137 (sometimes Lys) is conserved, suggesting that a phospho-compound will not be its target substrate. It is not possible to guess at the reaction performed in this putative second type of active site. However, these observations suggest many avenues for further exploration of LacAB structure and function.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of protein

RpiB from E. coli DH5α genomic DNA was cloned into the expression vector pET15b (Novagen, WI, USA); this construct provides for an N-terminal His6-tag that can be cleaved off if necessary with thrombin. RpiB was expressed, purified and prepared for crystallization studies as described.9,29 For the preparation of the seleno-methionine (Se-Met) enriched protein from this construct, RpiB was expressed in the methionine auxotroph strain E. coli B834(DE3) (Novagen) in supplemented M9 medium. The Se-Met protein was purified as for the native protein, except that 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol was added to the purification buffers.

The gene was amplified by PCR using the plasmid from the first construct, to introduce a different, shorter, N-terminal His6-tag (MAHHHHHHSG), and a C-terminal primer containing an altered terminal codon (TAG changed to TGA). The amplified gene fragment was treated with Taq polymerase for production of a 3′ A-overhang and ligated directly into pCRT7 TOPO TA (Invitrogen). The cells were grown in LB at 37 °C to an A550 ∼0.6 and expression induced with 0.020%(w/v) l-arabinose (final concentration). Growth was continued at 28 °C for four hours, after which the cells were harvested, resuspended in binding buffer (200 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid (MESNA)), and frozen at −20 °C. Thawed cells were broken by sonication after the addition of RNase A and DNase I (10 μg/ml and 20 μg/ml, respectively). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation (45 minutes at 18,000 rpm; RC5C, Sorvall Instruments). The supernatant was then applied to a metal chelate affinity column charged with Co2+ (Talon; Clontech). After the column was washed, the protein was eluted using binding buffer plus 300 mM imidazole. Fractions containing RpiB were dialyzed into 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 5 mM MESNA, then concentrated using a Vivaspin concentrator (Vivascience).

Both versions of RpiB could be stored successfully at +8 °C (short term) or at −20 °C (long term). For long-term storage at +8 °C, the first construct appeared to be slightly more stable.

Assays

The ketose, ribulose 5-phosphate, absorbs UV light at 290 nm, which provides the basis for a simple and direct spectrophotometric assay.30 Reaction mixtures typically contained 30 nM enzyme in a buffer of 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl. As DTT and DTE absorb in the UV region, 5 mM MESNA was used as a reducing agent. After addition of enzyme to initiate the reaction (generally 5 μl of a 0.1 mg/ml stock, for a final reaction volume of 1 ml), the increase in absorbance was measured at 37 °C. Ribose 5-phosphate (Fluka) concentrations covered the range from 0.4 to 24 times the Km (rates were difficult to measure at lower substrate concentrations). Arabinose 5-phosphate (Sigma) and fructose 6-phosphate (Sigma) and other sugars were tested at various concentrations. All kinetic parameters were calculated from Hanes–Woolf plots (i.e. [S]/v versus [S]).

Dynamic light-scattering experiments

Dynamic light-scattering (DLS) exeriments were performed using a DynaPro-801 TC (Protein Solutions Inc.). All measurements were performed at 25 °C in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MESNA. The protein concentration was 21 mg/ml.

Crystallization, data collection, structure solution and refinement

Any particulate matter was removed from the samples by passage through a 0.2 μm Nanosep MF centrifugal filtration device (Pall-Gelman). The apo Se-Met protein could be crystallized by vapor diffusion in hanging drops, mixing 2 μl of protein solution with 2 μl of a reservoir solution containing 5 M NaCl, 0.05 M Hepes (with sodium as counter-ion), pH 6.8–7.5. For diffraction studies, the crystals were flash-frozen directly from the crystallization drop without additional cryoprotectants.

Diffraction data were collected at 100 K at the 19ID beamline of the Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. The absorption edge was determined by a fluorescent scan of the crystal as described.31 The three-wavelength MAD data (peak: 0.9777 Å, inflection point: 0.9779 Å, high remote: 0.95374 Å) were collected from a Se-Met-substituted protein crystal using an inverse-beam strategy. One crystal was used to collect all MAD data sets up to 2.2 Å resolution, with five seconds exposure/frame, 200 mm crystal-to-detector distance, 0.5° oscillation up to 100°, using a modified HKL2000 data collection strategy.32 Data were processed and scaled using HKL2000; statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Patterson searches, MAD phasing, density modification, initial map calculation and structure refinement were carried out using the CNS suite.33 Electron density maps of the Se-Met-labeled enzyme (phased using two Se-Met/molecule, eight total per asymmetric unit) at 2.4 Å resolution were of sufficient quality (Figure 3) to allow auto-tracing of the amino acid chain using the program wARP.34 This procedure provided an initial model consisting of 88 out of 161 amino acid residues per subunit (including the N-terminal expression tag). Subsequent manual adjustment using QUANTA (Accelrys, Inc.) allowed 70 more residues to be built. The structure was then refined to 2.2 Å resolution against the reprocessed remote data, using the experimental (MAD) phases as restraints throughout (refinement target:mlhl). Further manual adjustment was carried out with the aid of fourfold averaged maps, using QUANTA (Molecular Simulations, Inc., San Diego). A total of 299 water molecules were added using the program Waterpick in the CNS suite. The final R-factor was 21.7% and the Rfree was 26.3% with all the data included to 2.2 Å resolution (Table 2). Well-defined electron density was observed for all residues from 1 to 146/147 of all four molecules in the asymmetric unit, as well as 12–13 residues of the N-terminal tag sequence. A strict-boundary Ramachandran plot35 showed 1.3% of the non-glycine residues were outliers, well within the acceptable range for structures at this resolution. The Gly-Thr sequence at residues 34–35 exhibits an unusual non-proline cis peptide bond in all four subunits.

Structural analysis, sequence and structural comparisons

Surface-accessibility calculations were carried out using the algorithm described by Lee & Richards,36 with a probe radius of 1.4 Å. The subunit contact surfaces were analyzed with the aid of published methods.11 Similar structures were located using the DALI server,17 TOP,37 and hidden Markov models.38 Structures were also compared using the brute and imp options of the program LSQMAN,39,40 and with the graphics program O.41 Figures were prepared with O and OPLOT,42 Molray,43 MOLSCRIPT,44 and Canvas (Deneba Systems, Inc.).

Protein Data Bank accession number

Atomic coordinates and structure factor data have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank16 with an entry code of 1NN4.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Structural Biology Center at Argonne National Laboratory for their help in conducting experiments, and Steven Beasley for assisting in the preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM62414, the Ontario Research and Development Challenge Fund, and by the US Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under contract W-31-109-Eng-38. C.H.A. and A.M.E. are CIHR Scientists. S.L.M. and C.E.A. were supported by the Swedish Natural Science Research Council, by Uppsala University and by the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; these authors thank Annette Roos and Torsten Unge for help with the second RpiB construct.

Abbreviations used

- r.m.s.

root-mean-square

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- MAD

multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion

Footnotes

The submitted paper has been created by the University of Chicago as Operator of Argonne National Laboratory (“Argonne”) under Contract No. W-31-109-ENG-38 with the U.S. Department of Energy. The U.S. Government retains for itself, and others acting on its behalf, a paid-up, non-exclusive, irrevocable worldwide license in said article to reproduce, prepare derivative works, distribute copies to the public, and perform publicly and display publicly, by or on behalf of the Government.

References

- 1.David J, Wiesmeyer H. Regulation of ribose metabolism in Escherichia coli. II. Evidence for two ribose-5-phosphate isomerase activities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;208:56–67. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(70)90048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Essenberg MK, Cooper RA. Two ribose-5-phosphate isomerases from Escherichia coli K12: partial characterisation of the enzymes and consideration of their possible physiological roles. Eur J Biochem. 1975;55:323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorensen KI, Hove-Jensen B. Ribose catabolism of Escherichia coli: characterization of the rpiB gene encoding ribose phosphate isomerase B and of the rpiR gene, which is involved in regulation of rpiB expression. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1003–1011. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1003-1011.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skinner AJ, Cooper RA. The regulation of ribose-5-phosphate isomerization in Escherichia coli K12. FEBS Letters. 1971;12:293–296. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(71)80202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim C, Song S, Park C. The d-allose operon of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7631–7637. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7631-7637.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poulsen TS, Chang YY, Hove-Jensen B. d-Allose catabolism of Escherichia coli: involvement of alsI and regulation of als regulon expression by allose and ribose. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7126–7130. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.22.7126-7130.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishikawa K, Matsui I, Payan F, Cambillau C, Ishida H, Kawarabayasi Y, et al. A hyperthermostable d-ribose-5-phosphate isomerase from Pyrococcus horikoshii: characterization and three-dimensional structure. Structure (Camb) 2002;10:877–886. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00779-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rangarajan ES, Sivaraman J, Matte A, Cygler M. Crystal structure of d-ribose-5-phosphate isomerase (RpiA) from Escherichia coli. Proteins: Struct Funct Genet. 2002;48:737–740. doi: 10.1002/prot.10203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang R, Andersson CE, Savchenko A, Skarina T, Evdokimova E, Beasley S, et al. Structure of Escherichia coli ribose-5-phosphate isomerase: a ubiquitous enzyme of the pentose phosphate pathway and the Calvin cycle. Structure (Camb) 2003;11:31–42. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossmann MG, Moras D, Olsen KW. Chemical and biological evolution of a nucleotide-binding protein. Nature. 1974;250:194–199. doi: 10.1038/250194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones S, Thornton JM. Principles of protein–protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bateman A, Birney E, Cerruti L, Durbin R, Etwiller L, Eddy SR, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucl Acids Res. 2002;30:276–280. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pang Q, Hays JB, Rajagopal I, Schaefer TS. Selection of Arabidopsis cDNAs that partially correct phenotypes of Escherichia coli DNA-damage-sensitive mutants and analysis of two plant cDNAs that appear to express UV-specific dark repair activities. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:411–426. doi: 10.1007/BF00015972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Rooijen RJ, van Schalkwijk S, de Vos WM. Molecular cloning, characterization, and nucleotide sequence of the tagatose 6-phosphate pathway gene cluster of the lactose operon of Lactococcus lactis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7176–7181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosey EL, Oskouian B, Stewart GC. Lactose metabolism by Staphylococcus aureus: characterization of lacABCD, the structural genes of the tagatose 6-phosphate pathway. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5992–5998. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.5992-5998.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucl Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm L, Sander C. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braden BC, Velikovsky CA, Cauerhff AA, Polikarpov I, Goldbaum FA. Divergence in macromolecular assembly: X-ray crystallographic structure analysis of lumazine synthase from Brucella abortus. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:1031–1036. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drennan CL, Huang S, Drummond JT, Matthews RG, Lidwig ML. How a protein binds B12: a 3.0 Å X-ray structure of B12-binding domains of methionine synthase. Science. 1994;266:1669–1674. doi: 10.1126/science.7992050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathews II, Kappock TJ, Stubbe J, Ealick SE. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli PurE, an unusual mutase in the purine biosynthetic pathway. Struct Fold Des. 1999;7:1395–1406. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)80029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang KY, Cho CS, Kim SS, Sung HC, Yu YG, Cho Y. Structure and mechanism of glutamate racemase from Aquifex pyrophilus. Nature Struct Biol. 1999;6:422–426. doi: 10.1038/8223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng YJ, Merz KM, Jr, Farber GK. Theoretical examination of the mechanism of aldose–ketose isomerization. Protein Eng. 1993;6:479–484. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrell HL, Hoier H, Glusker JP. Modes of binding substrates and their analogs to the enzyme d-xylose isomerase. Acta Crystallog sect D. 1994;50:113–123. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993009345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pierce J, Serianni AS, Barker R. Anomerization of furanose sugars and sugar phosphates. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:2448–2456. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung CH, Hartman FC, Lu TY, Larimer FW. d-Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase from spinach: heterologous overexpression, purification, characterization, and site-directed mutagenesis of the recombinant enzyme. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;373:409–417. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komives EA, Chang LC, Lolis E, Tilton RF, Petsko GA, Knowles JR. Electrophilic catalysis in triosephosphate isomerase: the role of histidine-95. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3011–3019. doi: 10.1021/bi00226a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feierberg I, Åqvist J. Computational modeling of enzymatic keto–enol isomerization reactions. Theor Chem Accts. 2002;108:71–84. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bissett DL, Wenger WC, Anderson RL. Lactose and d-galactose metabolism in Staphylococcus aureus. II. Isomerization of d-galactose 6-phosphate to d-tagatose 6-phosphate by a specific d-galactose-6-phosphate isomerase. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:8740–8744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang RG, Kim Y, Skarina T, Beasley S, Laskowski R, Arrowsmith C, et al. Crystal structure of Thermotoga maritima 0065, a member of the IclR transcriptional factor family. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19183–19190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112171200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wood T. Spectrophotometric assay for d-ribose-5-phosphateketol-isomerase and for d-ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase. Anal Biochem. 1970;33:297–306. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh MA, Dementieva I, Evans G, Sanishvili R, Joachimiak A. Taking MAD to the extreme: ultrafast protein structure determination. Acta Crystallog sect D. 1999;55:1168–1173. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999003698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. Crystallography and nMR system (CNS): a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallog sect D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perrakis A, Sixma TK, Wilson KS, Lamzin VS. wARP: improvement and extension of crystallogaphic phases by weighted averaging of multiple-refined dummy atomic models. Acta Crystallog sect D. 1997;53:448–455. doi: 10.1107/S0907444997005696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. Phi/Psi-cology: Ramachandran revisited. Structure. 1996;4:1395–1400. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee B, Richards FM. The interpretation of protein structures: estimation of static accessibility. J Mol Biol. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu G. TOP: a new method for protein structure comparisons and similarity searches. J Appl Crystallog. 2000;33:176–183. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karplus K, Barrett C, Hughey R. Hidden Markov models for detecting remote protein homologies. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:846–856. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.10.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleywegt GJ. Use of non-crystallographic symmetry in protein structure refinement. Acta Crystallog sect D. 1996;52:842–857. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995016477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. Detecting folding motifs and similarities in protein structures. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:525–545. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallog sect A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones TA, Kjeldgaard MO. Electron-density map interpretation. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:173–208. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris M, Jones TA. Molray—a web interface between O and the POV-Ray ray tracer. Acta Crystallog sect D. 2001;57:1201–1203. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901007697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kraulis P. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J Appl Crystallog. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]