Abstract

Background

Several studies suggest yoga may be effective for chronic low back pain; however, trials targeting minorities have not been conducted.

Primary Study Objectives

Assess the feasibility of studying yoga in a predominantly minority population with chronic low back pain. Collect preliminary data to plan a larger powered study.

Study Design

Pilot randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Two community health centers in a racially diverse neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts.

Participants

Thirty English-speaking adults (mean age 44 years, 83% female, 83% racial/ethnic minorities; 48% with incomes ≤$30000) with moderate-to-severe chronic low back pain.

Interventions

Standardized series of weekly hatha yoga classes for 12 weeks compared to a waitlist usual care control.

Outcome Measures

Feasibility measured by time to complete enrollment, proportion of racial/ethnic minorities enrolled, retention rates, and adverse events. Primary efficacy outcomes were changes from baseline to 12 weeks in pain score (0=no pain to 10=worst possible pain) and back-related function using the modified Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (0–23 point scale, higher scores reflect poorer function). Secondary efficacy outcomes were analgesic use, global improvement, and quality of life (SF-36).

Results

Recruitment took 2 months. Retention rates were 97% at 12 weeks and 77% at 26 weeks. Mean pain scores for yoga decreased from baseline to 12 weeks (6.7 to 4.4) compared to usual care, which decreased from 7.5 to 7.1 (P=.02). Mean Roland scores for yoga decreased from 14.5 to 8.2 compared to usual care, which decreased from 16.1 to 12.5 (P=.28). At 12 weeks, yoga compared to usual care participants reported less analgesic use (13% vs 73%, P=.003), less opiate use (0% vs 33%, P=.04), and greater overall improvement (73% vs 27%, P=.03). There were no differences in SF-36 scores and no serious adverse events.

Conclusion

A yoga study intervention in a predominantly minority population with chronic low back pain was moderately feasible and may be more effective than usual care for reducing pain and pain medication use.

Low back pain is the most common cause of pain in the United States1,2 resulting in substantial morbidity,3 disability,4,5 and cost to society.6,7 An estimated 5% to 10% of US adults experience chronic low back pain (CLBP).1,2,5 Individuals from low-income minority backgrounds with CLBP may be disproportionately affected due to disparities in access to treatment. For example, minorities have less access to analgesic prescriptions,8 surgery,9 and intensive rehabilitation.10

Many CLBP patients seek relief using complementary therapies such as yoga.11,12 Yoga originated over 2000 years ago in India as a system of physical, moral, and spiritual practices.13 Hatha yoga is one branch of yoga consisting of physical postures (asanas), breathing techniques (pranayama), and meditation. Although yoga use by adults in the United States increased to more than 6% in 2007,12,14,15 it is less common among minorities and individuals with lower incomes or education.12,14 Several studies of yoga for CLBP in predominantly white middle-class populations suggest it may be effective for reducing pain and improving function.16–20 A practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and American Pain Society lists a specific style of hatha yoga called Viniyoga as having fair evidence for a moderate benefit for CLBP.21 The feasibility and effectiveness of offering any style of yoga intervention in minority populations with chronic low back pain has not been assessed, however. Our objective, therefore, was to assess the feasibility of offering a hatha yoga intervention for a predominantly minority population with CLBP and collect preliminary data in order to plan a future adequately powered trial.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial for adults with chronic low back pain recruited from 2 community health centers (CHCs) that serve a racially diverse, low-income neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. Participants were randomly assigned to a standardized 12-week protocol of hatha yoga classes or a usual care waitlist control group. We used computer-generated permuted block randomization. Treatment assignments were placed in opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes prepared by a biostatistician (RBD) who had no contact with participants. The study was approved by the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and the CHCs’ research committees.

Study Participants

To recruit our target of 30 participants for this pilot study, we posted flyers in exam rooms and waiting room areas in the CHCs and surrounding community. A community newspaper and radio station carried study advertisements. We informed providers and staff members about the trial through presentations and e-mails. Using the CHCs’ electronic medical records, we identified patients seen in the last 2 years with a low back pain diagnosis and generated recruitment letters for their providers to sign and send.

Participants needed to be 18 to 64 years old and have current low back pain persisting ≥12 weeks. Mean pain intensity for the 2 weeks prior to enrollment needed to be ≥4 on a numerical rating scale of 0 to 10. Sufficient understanding of English to follow class instructions and complete surveys was required. Exclusion criteria included yoga use in the previous year; new pain medicine or other low back pain treatments started within the previous month or anticipated to begin in the next 6 months; pregnancy; back surgery in the previous 3 years; nonmuscular pathologies (eg, spinal canal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, infection, malignancy, fracture); severe or progressive neurological deficits; sciatica pain equal to or greater than back pain; active substance or alcohol abuse; serious systemic disease, medical, or psychiatric comorbidities precluding yoga practice; active or planned worker’s compensation, disability, or personal injury claims; and inability to attend classes at the times and location offered.

Interested individuals were initially screened for eligibility by telephone after oral informed consent was obtained. If individuals appeared eligible, they were invited to meet with research staff. At the first meeting, we obtained written informed consent to verify eligibility criteria and asked them to record their daily pain intensity for 2 weeks on an 11-point numerical rating scale. Two weeks later at the second meeting, we confirmed their average weekly pain intensity was ≥4, collected baseline data, and randomized them.

Yoga Intervention

We developed a reproducible standardized hatha yoga intervention for CLBP intended for individuals with little or no yoga experience. We searched Medline, Alt HealthWatch, and Cochrane for papers on yoga and low back pain. Non-peer reviewed books, periodicals, and videos on yoga for low back pain were identified through searching an online bookstore (Amazon.com), an annotated bibliography,22 and websites on the first 2 pages of a Google Internet search using keywords “yoga” and “back pain.” We collected and distributed these materials to an expert panel consisting of 2 national yoga experts, a yoga instructor for the study (DCD), and the principal investigator (RBS). Panel members had expertise in several popular styles of hatha yoga including Anusara, Ashtanga, Iyengar, and Kripalu. One member had special expertise in yoga programs for minority women. Panel members reviewed the information before meeting in March 2006. At the meeting, they synthesized information from the literature with their experience to draft a protocol that was subsequently refined iteratively through discussion, consensus, and use in nonstudy yoga classes.

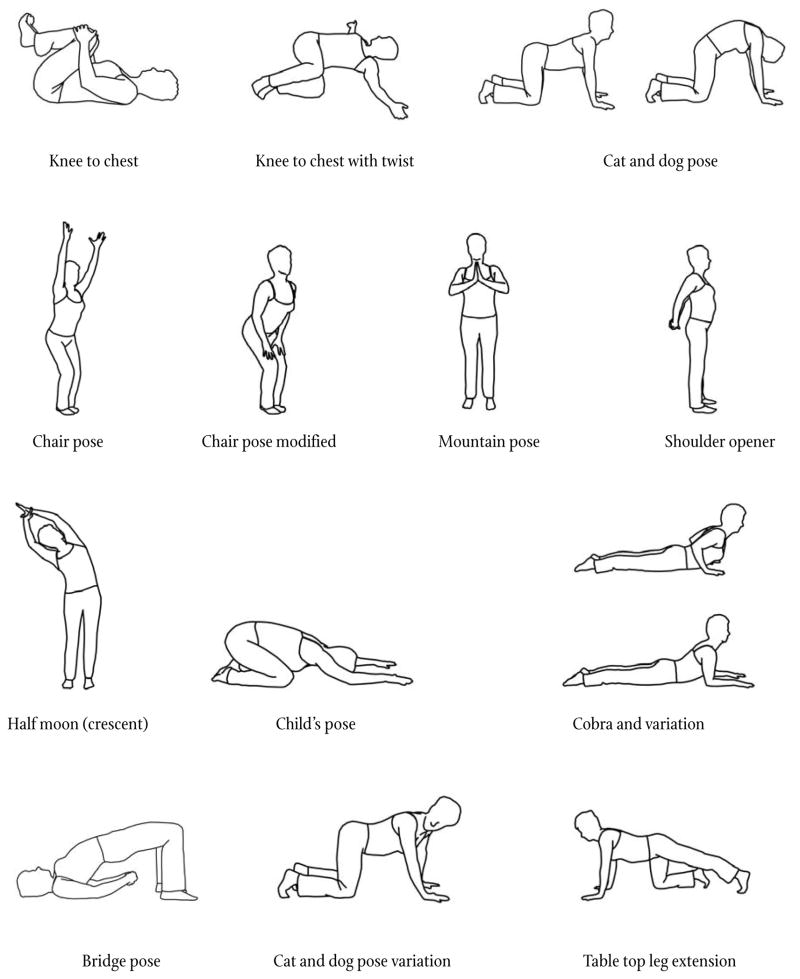

The final protocol consisted of 12 weekly 75-minute yoga classes divided into four 3-week segments (Appendix Table and Figure). Each segment was given a theme, such as “Listening to the Wisdom of the Body” and “Engaging Your Power.” Each class began and ended with Svasana, a relaxation exercise. Classes included postures and breathing techniques. Each segment built upon the previous segment. The protocol provided variations and used various aids (eg, chair, strap, block) to accommodate different abilities. A variety of world music was used during the classes. Classes were limited to 8 participants, occurred at one CHC, and were taught by a team of 2 female yoga instructors, 1 white and 1 African American. Both were registered yoga teachers with Yoga Alliance, and each had approximately 4 years of teaching experience. Home practice for 30 minutes daily was strongly encouraged. We provided participants with an audio CD of the protocol; a portable CD player; a handbook describing and depicting the exercises; and a yoga mat, strap, and block. The 2 national yoga experts from the panel observed several classes in person to provide feedback to the instructors on accurate, effective, and safe protocol delivery.

APPENDIX TABLE.

12-week Standardized Hatha Yoga Protocol for the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain

| Yoga Posture (Asana) | Classes Incorporating Posture by Segment | Total Classes Incorporating Posture | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segment 1 | Segment 2 | Segment 3 | Segment 4 | ||

| Weeks 1–3 | Weeks 4–6 | Weeks 7–9 | Weeks 10–12 | ||

| Opening to Something Greater | Listening to the Wisdom of the Body | Engaging Your Power | Bringing it Home | ||

| Svasana relaxation and breathing exercises* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Knee to chest* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Knee to chest with twist* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Pelvic clocks* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Cat and dog pose (and modifications)* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Chair pose (and modified)* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Mountain pose* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Shoulder opener* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Half moon* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Child’s pose* | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 | |

| Cobra (original and modified)* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Bridge pose* | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 | |

| Reclining cobbler* | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 | |

| Downward-facing dog (and modified at wall)* | Yes | Yes | 6 | ||

| Triangle pose at wall | Yes | 3 | |||

| Locust pose | Yes | 3 | |||

| Reclining big toe pose | Yes | Yes | 6 | ||

| Warrior I pose | Yes | Yes | 6 | ||

| Downward-facing dog | Yes | 3 | |||

| Lunge with wall assist | Yes | Yes | 6 | ||

| Standing squat with half forward bend | Yes | 3 | |||

| Baby dancer pose | Yes | 3 | |||

| Deep lunge | Yes | 3 | |||

| Spinal rolls | Yes | 3 | |||

| Svasana relaxation and breathing exercises* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

The hatha yoga protocol developed for chronic low back pain patients consisted of 12 weekly 75-minute yoga classes divided into four 3-week segments. Each segment was given a theme. The exercises for each segment are indicated in the Table. The sequence of exercises for each segment follows the order provided in the Table. Each class began and ended with Svasana, a relaxation exercise. The protocol provided for variations of poses to accommodate different abilities.

Exercises included on the audio CD provided to participants for home practice.

APPENDIX FIGURE.

The yoga postures (asanas) shown were part of a standardized hatha yoga protocol developed for chronic low back pain in individuals with little or no yoga experience. To design the protocol, we performed a systematic search of the peer-reviewed and lay literature on yoga for low back pain. We collected and distributed this literature to an expert panel with a broad range of experience in different yoga styles. After reviewing the literature, the panel met and synthesized information from the literature with their professional experience to draft a protocol that was subsequently refined iteratively through discussion, consensus, and use in nonstudy yoga classes.

Usual Care Control Group

Both groups continued to receive their routine medical care and medications. The usual care control participants were offered the yoga intervention after 26 weeks. Both groups received an educational book used in previous low back pain studies23 that describes self-care management strategies for low back pain. Both groups were discouraged from starting any new back pain treatments during the study.

Data Collection

We collected baseline sociodemographic data and back pain history including duration, sciatica, and previous treatments such as physical therapy, epidural steroid injections, and CAM. Outcome data were collected at 6, 12, and 26 weeks.

Feasibility outcomes related to recruitment (time to complete enrollment, proportion of racial and ethnic minorities enrolled), participant retention, adherence to treatment allocation (class attendance, home practice, use of nonstudy treatments), and safety were measured through weekly adverse event logs.

There were 2 primary outcomes of efficacy measured at 12 weeks: (1) average pain level for the previous week using an 11-point numerical rating scale (0=no pain to 10=worst possible pain);24,25 and (2) back-related function using the modified Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire,26 a 23-item reliable validated instrument measuring the number of activities of daily living limited due to back pain. Scores can range from 0 to 23 with higher scores reflecting poorer back-related function.

Secondary efficacy outcomes included use of pain medication during the preceding week; global improvement using a 7-point Likert scale (0=extremely worsened to 6=extremely improved); and health-related quality of life using the SF-36.27

Participants and yoga teachers could not be blinded to treatment allocation. All study participants met in person with unblinded research staff members to complete paper questionnaires at baseline, 6, and 12 weeks. We also attempted to collect follow-up data at 26 weeks. After completing each survey, participants received honoraria for study participation and defraying transportation costs: $25 at baseline, $25 at 6 weeks, $50 at 12 weeks, and $25 at 26 weeks. Blinded data-entry staff used double entry verification to minimize error.

Data Analysis

Baseline data for the 2 groups were compared using Student’s t-test for continuous variables, Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables, and chi-square test of independence for categorical variables. Feasibility outcomes were summarized with descriptive statistics. For the primary efficacy outcomes pain and function, we calculated change scores by subtracting 12-week data from baseline. Change scores for each group had a non-normal distribution and were therefore compared using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. We also completed a post-hoc analysis of the proportion of individuals experiencing a minimal clinically significant decrease in the primary outcomes at 12 weeks (≥2 points for pain28 and ≥30% decrease from baseline for the Roland29) using Fisher’s exact test.

For the secondary efficacy outcomes, we compared change in pain medication use between groups at 6 and 12 weeks using exact logistic regression. Medication use was the dependent variable, and baseline medication use and group assignment were the independent variables. Global improvement at 12 weeks was dichotomized into improved vs no change or worse. Proportions of improved participants in the 2 groups were compared with Fisher’s exact test. Change scores for the SF-36 physical and mental health components were also compared with Wilcoxon Rank Sum.

All analyses used an intention-to-treat approach and a 2-sided P criteria of <.05 for statistical significance. Missing data were imputed using the last-value-carried-forward approach. We used LogXact software (Cytel, Cambridge, Massachusetts) for logistic regression analyses and SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) for all others.

RESULTS

Feasibility Outcomes

Patient Recruitment and Retention

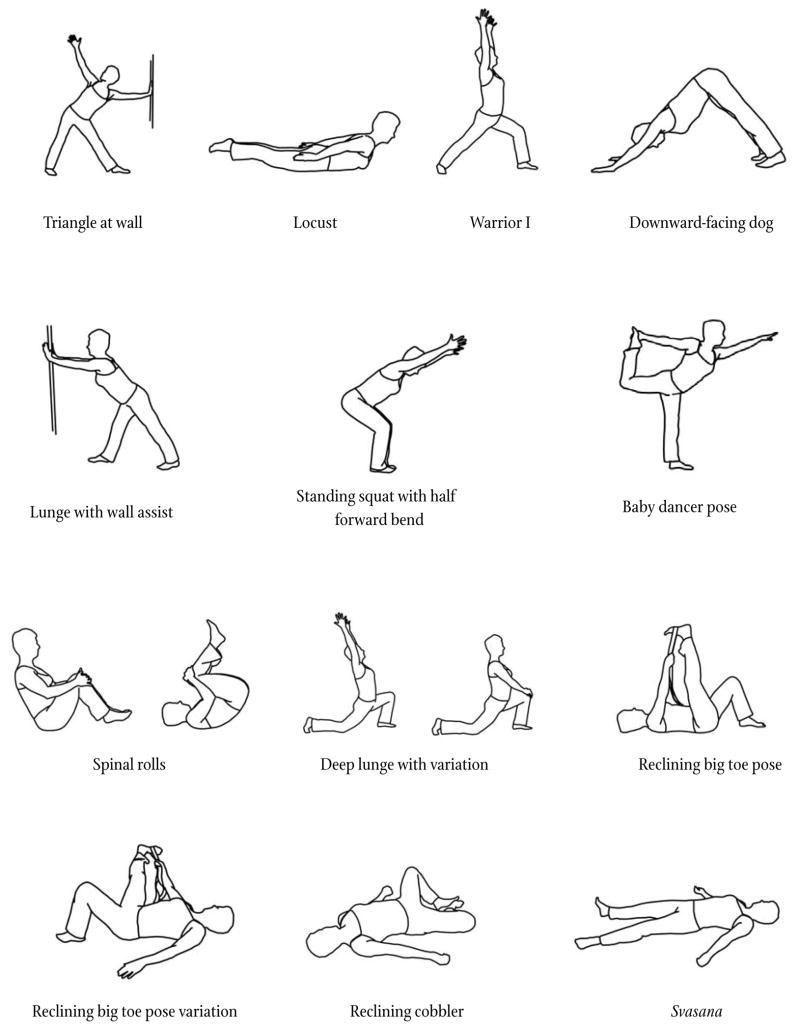

We received more than 200 inquiries about the study from February to March 2007 (Figure 1). Over 2 months, we needed to screen 66 individuals in the order they contacted us to enroll 30 participants. The most common reasons for exclusion were severe sciatica and insufficient severity of low back pain. The Table describes baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants. Eighty-three percent were racial or ethnic minorities. A majority were female, unemployed, or working part-time. Almost half had annual household incomes ≤$30000 and public-funded health insurance coverage. Previous practice of yoga was rare. Mean pain and Roland scores for the study sample were high and consistent with moderate-to-severe chronic low back pain. Comorbidities such as osteoarthritis, obesity, diabetes, and depression were common (data not shown). No statistically significant differences between groups at baseline were observed. Participant retention was 97% at 12 weeks and 77% at 26 weeks. We were unable to collect 26-week data from 7 members of the yoga group.

FIGURE 1.

Participant Flow Diagram

TABLE.

Baseline Characteristics of 30 Individuals With Chronic Low Back Pain Randomized to 12 Weeks of Yoga Classes or a Usual Care Waitlist Control Group

| Characteristic | Treatment Group | Total (n=30) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yoga (n=15) | Usual Care (n=15) | ||

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Mean age (SD), years | 44 (13) | 44 (11) | 44 (12) |

| Women, no. (%) | 11 (73) | 14 (93) | 25 (83) |

| Highest level of education, no. (%) | |||

| High school graduate or less | 4 (27) | 6 (40) | 10 (33) |

| Some college | 4 (27) | 9 (60) | 13 (43) |

| College graduate | 7 (46) | 0 | 7 (24) |

| Race, no. (%) | |||

| White | 3 (20) | 4 (27) | 7 (24) |

| Black* | 11 (73) | 10 (66) | 21 (70) |

| Asian† | 1 (7) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Native American | 0 | 1 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Hispanic, no. (%) | 2 (13) | 2 (13) | 4 (13) |

| Non-white and/or Hispanic, no. (%) | 13 (87) | 12 (80) | 25 (83) |

| Born outside United States, no. (%) | 7 (47) | 2 (13) | 9 (30) |

| Annual household income, no. (%) | |||

| ≤$10,000 | 2 (13) | 6 (40) | 8 (27) |

| $10001–$30000 | 2 (13) | 3 (20) | 5 (17) |

| $30001–$50000 | 5 (33) | 3 (20) | 8 (27) |

| >$50000 | 3 (20) | 3 (20) | 6 (20) |

| Unknown | 3 (20) | 0 | 3 (10) |

| Employment, no. (%) | |||

| Full-time | 6 (40) | 6 (40) | 12 (40) |

| Part-time | 4 (27) | 5 (33) | 9 (30) |

| Unemployed due to back pain | 3 (20) | 3 (20) | 6 (20) |

| Unemployed due to other causes | 2 (13) | 1 (7) | 3 (10) |

| Health insurance, no. (%) | |||

| Private (HMO, PPO) | 8 (53) | 7 (47) | 15 (50) |

| Public | |||

| Medicaid | 2 (13) | 5 (33) | 7 (23) |

| “Free Care”‡ | 4 (27) | 2 (13) | 6 (20) |

| Medicare | 1 (7) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| None | 0 | 1 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Religious preference, no. (%) | |||

| Protestant§ | 7 (47) | 6 (40) | 13 (44) |

| Roman Catholic | 2 (13) | 4 (27) | 6 (20) |

| Muslim | 1 (7) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Santeria | 0 | 1 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Jehovah’s Witness | 1 (7) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| None or unknown | 4 (26) | 4 (26) | 8 (26) |

| Back Pain History | |||

| Initial onset >1 year ago, no. (%) | 15 (100) | 15 (100) | 30 (100) |

| Current episode began >1 year ago, no. (%) | 13 (87) | 11 (73) | 24 (80) |

| Pain radiates below knee, no. (%) | 5 (33) | 7 (47) | 12 (40) |

| >45 days pain in past 3 months, no. (%) | 13 (87) | 8 (53) | 21 (70) |

| >1 day of lost work in past month, no. (%) | 4 (27) | 3 (20) | 7 (23) |

| >7 days of restricted activity in past month, no. (%) | 11 (73) | 9 (60) | 20 (67) |

| Back pain treatments previously used, no. (%) | |||

| Physical therapy | 10 (67) | 12 (80) | 22 (73) |

| Exercise | 10 (67) | 14 (93) | 24 (80) |

| Epidural steroid injections | 2 (13) | 5 (33) | 7 (23) |

| Back surgery | 0 | 2 (13) | 2 (7) |

| Massage | 10 (67) | 10 (67) | 20 (67) |

| Chiropractic | 6 (40) | 6 (40) | 12 (40) |

| Acupuncture | 3 (20) | 5 (33) | 8 (27) |

| Yoga | 3 (20) | 1 (7) | 4 (13) |

| Baseline Outcome Measures | |||

| Mean pain score during past week (11-point scale) (SD) | 6.7 (1.9) | 7.5 (1.3) | 7.1 (1.7) |

| Mean Roland disability score (23-point scale) (SD) | 14.5 (5.0) | 16.1 (4.0) | 15.3 (4.5) |

| Use of pain medication in past week, no. (%) | |||

| Any pain medication | 10 (67) | 11 (73) | 21 (70) |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | 4 (27) | 5 (33) | 9 (30) |

| Acetaminophen | 3 (20) | 4 (27) | 7 (23) |

| Opiates | 2 (13) | 3 (20) | 4 (13) |

| Muscle relaxants | 1 (7) | 3 (20) | 4 (13) |

| Other pain medication | 2 (13) | 3 (20) | 5 (17) |

| Mean SF-36 physical component score (SD) | 40 (8) | 34 (7) | 37 (8) |

| Mean SF-36 mental health component score (SD) | 47 (11) | 45 (11) | 46 (11) |

There were no statistically significant differences (P<.05) between baseline characteristics of the yoga and usual care waitlist control groups. SD indicates standard deviation; SF-36, Short-form 36 Health Survey.

The 21 black individuals in the sample included 15 African Americans and 6 Afro-Carribbeans (2 Jamaicans, 2 Haitians, 1 Barbadian, and 1 Trinidadian).

Bangladeshi.

Funded by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Free Care is a managed health plan that provided basic health insurance to uninsured low-income residents not meeting criteria for Medicaid.

Protestant religions included Baptist, Episcopalian, Presbyterian, United Methodist, and born-again Christian.

Treatment Adherence

Yoga participants attended a median of 8 classes (range 0–12), and 13 practiced at least once at home. One participant was not willing to attend any classes because of discomfort with groups but agreed to practice at home. Another individual avoided the Svasana component of the protocol due to a perceived conflict with his religion (Jehovah’s Witness). Thirteen yoga participants completed a mean of 6 home practice logs showing on average 4 days of home practice per week for 24 minutes per practice session. This was similar to what they reported on the 12-week questionnaire: 4 days per week and 38 minutes per session.

During the 12-week intervention period, use of any nonstudy treatments by yoga and control participants was 27% and 40%, respectively (P=.70) and included mostly physical therapy and acupuncture. Although no control group individuals reported yoga use during the 12-week intervention period, 5 reported starting yoga during the follow-up period. Use of any nonstudy treatments during the 12-to-26-week follow-up period increased to 100% for the 7 yoga participants and 87% for the usual care participants, respectively, and included new medications, physical therapy, epidural steroid injections, acupuncture, and chiropractic.

Safety

One yoga participant reported transient worsening of low back pain that improved after discontinuing yoga. No other significant adverse events were reported.

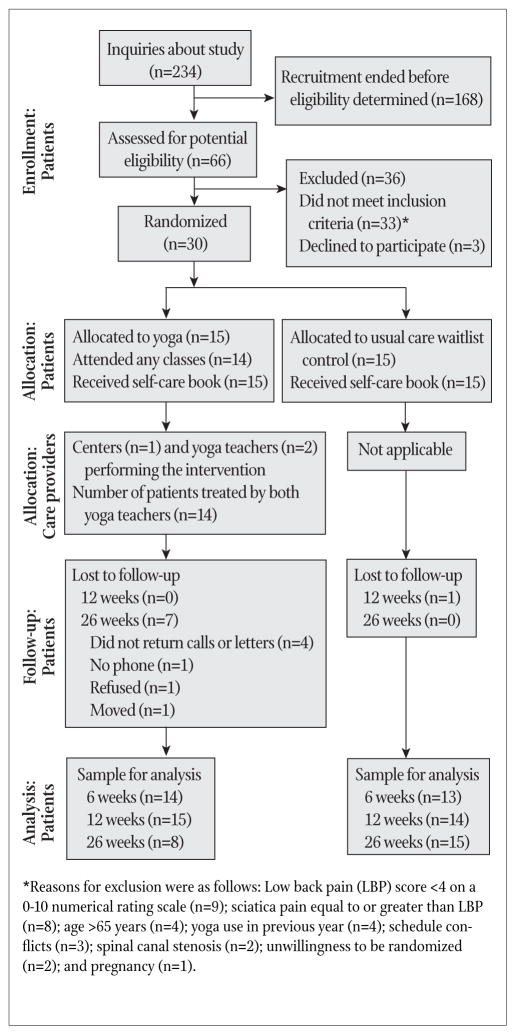

Primary Outcomes

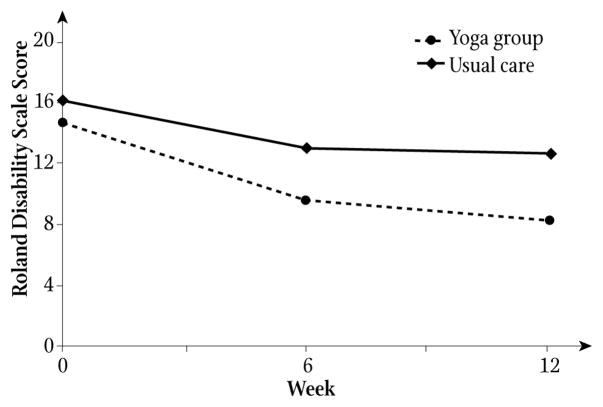

Mean pain scores for yoga participants decreased 2.3 points (SD 2.1) from baseline to 12 weeks compared to the control group, which decreased 0.4 points (SD 1.8, P=.02, Figure 2). Mean Roland scores for yoga participants decreased 6.3 points (SD 6.9) from baseline to 12 weeks compared to the control group, which decreased 3.7 points (SD 4.9, P=.28, Figure 3). The proportion of yoga participants experiencing a minimal clinically significant decrease in pain at 12 weeks was 67% vs 13% of control participants (OR 5.0, 95% CI 1.3–19.1, P=.008). For the Roland disability measure, 67% of yoga participants vs 40% of the control group had a minimal clinically significant decrease (OR 1.7, 95% CI 0.8–3.4, P=.27). None of our results changed significantly when outcomes were reanalyzed without imputing missing data.

FIGURE 2.

The x-axis is time from initiation of yoga classes. The y-axis is the mean low back pain intensity in the previous week on an 11-point numerical rating scale. The yoga group received hatha yoga classes weekly for 12 weeks. Both groups received an educational book on self-care management of low back pain and continued their usual medical care. P values for any difference in mean pain scores between groups (calculated by comparing mean pain change scores from baseline using the Wilcoxon rank sum test) are .25 and .02 at 6 and 12 weeks, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

The x-axis is time from initiation of yoga classes. The y-axis is the modified 23-point Roland Disability Scale mean score. Higher scores reflect worse back pain–related function. The yoga group received hatha yoga classes weekly for the first 12 weeks of the study. Both groups received an educational book on self-care management of low back pain and continued their usual medical care. P values for any difference in mean Roland Disability scores between groups (calculated by comparing mean Roland change scores from baseline using the Wilcoxon rank sum test) are .29 and .28 at 6 and 12 weeks, respectively.

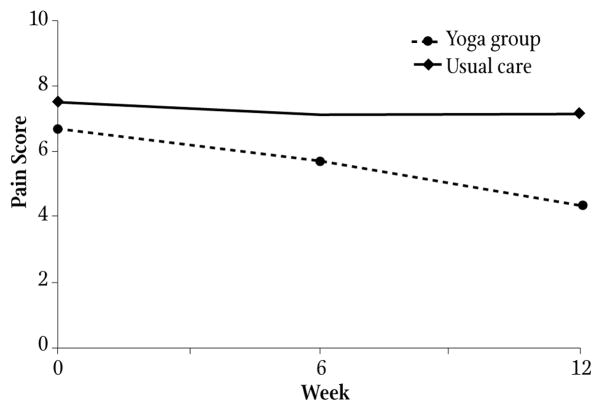

Secondary Outcomes

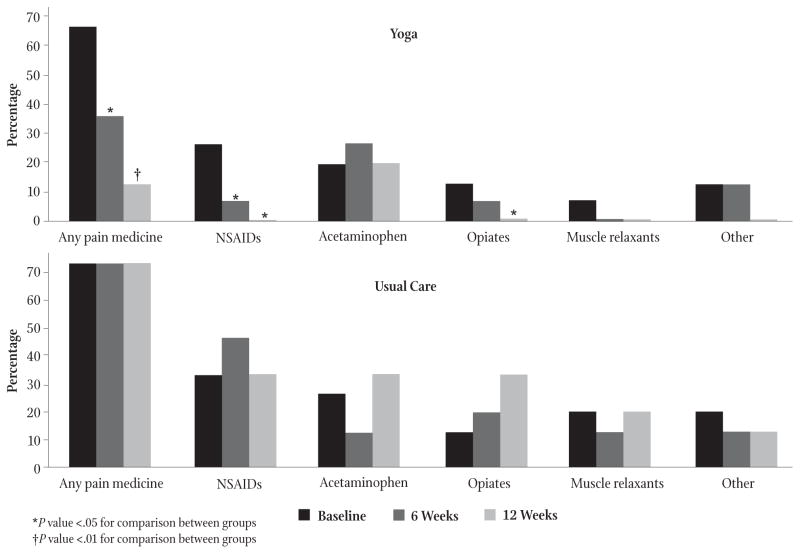

Use of any pain medicines during the previous week by yoga participants decreased from 67% to 13%, whereas use by usual care participants did not change (P=.003, Figure 4). Whereas opiate analgesic use by control participants during the 12th week increased to 33%, it decreased to zero for yoga participants (P=.04). Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and muscle relaxants showed similar patterns. At week 12, 73% of the yoga group compared to 27% of control participants reported global improvement in back pain (P=.03). SF-36 scores at 12 weeks did not differ significantly between groups.

FIGURE 4.

The top and bottom panels show pain medication use by the yoga and usual care groups, respectively. For each medication category, use at baseline, 6, and 12 weeks is displayed. Bar heights reflect the percentage of participants reporting any use within the previous week. Pain medication use was compared between groups at 6 and 12 weeks using exact logistic regression with 6-week or 12-week medication use as the dependent variable and baseline medication use and group assignment as the independent variables. Examples of “other” types of pain medicine included tramadol, gabapentin, and amitryptiline.

Long-term Follow-up

The mean pain and Roland scores at 26 weeks for the 8 yoga individuals we had data for were 3.9 (SD 0.6) and 6.6 (SD 2.6), respectively. We were able to collect data at 26 weeks from all 15 usual care participants. Compared to their 12-week data, their 26-week mean pain and Roland scores decreased to 4.5 (SD 1.2) and 8.3 (SD 2.9), respectively.

DISCUSSION

We found it was feasible to recruit and retain for 12 weeks a sample of predominantly minority adults for a pilot randomized controlled trial of a standardized hatha yoga intervention for chronic low back pain. Adherence to treatment assignment during the 12-week intervention period was good, with no serious adverse events. Yoga participants had statistically significant greater reduction in pain intensity and pain medication use at 12 weeks compared to individuals receiving usual care only. Beyond the 12-week intervention period, however, participant retention was poor and use of nonstudy treatments was high.

Although several studies3,6,8,9,30 have demonstrated racial and socioeconomic disparities in low back pain treatment and outcomes, few intervention studies for CLBP have targeted under-served populations. Our feasibility data illustrate some of the opportunities and challenges of such studies. The large number of respondents to our recruitment effort may reflect a significant interest in and unmet need for low back pain treatment among people living in these communities. This need may have contributed to impatience among the usual care group for their waitlist yoga classes to start and thereby led to high use of nonstudy treatments during the follow-up period. Basing the study in community health centers that were familiar and convenient to participants also may have facilitated recruitment. Obtaining long-term follow-up data of almost half of the yoga group was not possible, however, and may reflect loss of the regular structure and social support provided by the yoga classes.

Our preliminary efficacy results are consistent with previous yoga studies showing improvement of CLBP.16–20 Like our study, most trials were randomized16–18,20; included usual care and/or education controls16–18; employed a waitlist control design16,20; and measured standard back pain research outcomes such as pain17–20 and function.16–18,20 An important difference between our trial and prior studies is that our study included a more racially diverse patient population with lower incomes and less education. Furthermore, our participants reported considerably greater pain and worse function than individuals in other trials. For example, the largest study to date by Sherman et al enrolled a predominantly white college-educated middle-class sample with a mean baseline Roland score 7.2 points less than in our sample.17 Lastly, although prior yoga studies for CLBP also used a standardized yoga sequence, most used a specific yoga style such as Viniyoga,17 Iyengar,12 or Anusara19 rather than the more generic hatha yoga we employed. To date, no research suggests one yoga protocol or style is superior to another for low back pain.

There are multiple limitations to our study. The usual care group did not control for the increased attention and group support yoga participants may have received. These nonspecific aspects may have played a significant role in yoga’s effect. Lack of blinding and use of self-report measures may have further contributed to bias. The small sample size associated with our pilot design limits our statistical power. Nonrandom distribution of participant characteristics can also occur in small pilot trials. Furthermore, the impact of honoraria payments on recruitment, retention, and potential subject bias is uncertain. Regarding generalizability, it is unknown whether our findings can be replicated in other minority groups, multiple locations, nonresearch yoga programs, and with different yoga teachers. In addition, our findings apply only to patients with nonspecific CLBP as opposed to excluded conditions such as sciatica or spinal canal stenosis. Lastly, substantial loss to long-term follow-up in the yoga group and use of many nonstudy treatments including yoga by the control group preclude any meaningful conclusions from the 26-week data. Strengths of our study, however, include the randomized design, standardized reproducible yoga intervention, standard enrollment criteria and outcome measures used in other CLBP trials,31 community-based setting, and recruitment of a racial and socioeconomic diverse population with moderate-to-severe CLBP.

In summary, conducting a 12-week pilot randomized controlled trial of hatha yoga compared to usual care for an urban English-speaking predominantly minority sample with CLBP was moderately feasible. However, long-term retention and adherence to treatment assignment was poor. Yoga was more effective than usual care at least in the short term for reducing pain and pain medication use. Opportunities for future yoga and low back pain research in minorities include larger trials testing new strategies for improving long-term retention, adherence, and outcomes; comparing effectiveness and cost of yoga to other common back pain treatments; and targeting non-English speakers.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the study participants; Deborah Neubauer, RYT, and Maya Breuer, RYT, for assistance in designing the yoga protocol; Anna Dunwell, MFA, RYT, for helping teach the yoga classes; Nadia Khouri, MPH, Florence Uzogara, MA, Surya Karri, MBBS, MPH, Sasha Yakhkind, and Julia Keosaian for research assistance; and Stephen Tringale, MD, Tom Powers, and the providers and staff of Codman Square Health Center and Dorchester House Multiservice Center.

Support and Role of Sponsor

Dr Saper is supported by a Career Development Award (K07 AT002915-04) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Maryland. Dr Phillips is supported by a Mid-career Investigator Award (5K24AT000589-08) from NCCAM, NIH. NCCAM had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript for submission.

Footnotes

Data Access and Responsibility

Dr Saper had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributor Information

Robert B. Saper, Assistant professor and director of integrative medicine in the Department of Family Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts.

Karen J. Sherman, Senior scientific investigator at the Center for Health Studies, Group Health Cooperative, Seattle, Washington.

Diana Cullum-Dugan, Yoga teacher in private practice in Watertown, Massachusetts.

Roger B. Davis, Associate professor in the Division of General Internal Medicine and Primary Care, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and director of biostatistics in the Division for Research and Education in Complementary and Integrative Medical Therapies, Osher Research Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Russell S. Phillips, Chief of the Division of General Internal Medicine and Primary Care, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and director of fellowship training in the Division for Research and Education in Complementary and Integrative Medical Therapies, Osher Research Center.

Larry Culpepper, Professor in and chairman of the Department of Family Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center.

References

- 1.Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(5):363–370. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31(23):2724–2727. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Licciardone JC. The epidemiology and medical management of low back pain during ambulatory medical care visits in the United States. Osteopath Med Prim Care. 2008 Nov 24;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1750-4732-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo HR, Tanaka S, Halperin WE, Cameron LL. Back pain prevalence in US industry and estimates of lost workdays. Am ] Public Health. 1999;89(7):1029–1035. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.7.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):581–585. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo X, Pietrobon R, Sun SX, Liu GG, Hey L. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine. 2004;29(1):79–86. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000105527.13866.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK, et al. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA. 2008;299(6):656–664. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.6.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299(1):70–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carey TS, Garrett JM. The relation of race to outcomes and the use of health care services for acute low back pain. Spine. 2003;28(4):390–394. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000048499.25275.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Merys SC. Disability management of low back injuries by employer-retained physicians: ratings and costs. Am J Ind Med. 2000;39(5):529–538. doi: 10.1002/1097-0274(200011)38:5<529::aid-ajim5>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolsko PM, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Kessler R, Phillips RS. Patterns and perceptions of care for treatment of back and neck pain: results of a national survey. Spine. 2003;28(3):292–297. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000042225.88095.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Culpepper L, Phillips RS. Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga use in the United States: results of a national survey. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10(2):44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feuerstein G. The Yoga Tradition: Its History, Literature, Philosophy, and Practice. Prescott, AZ: Hohm Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB, Bertisch SM, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Characteristics of yoga users: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1653–1658. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0735-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. National Health Statistics Reports; Number 12. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galantino ML, Bzdewka TM, Eissler-Russo JL, et al. The impact of modified Hatha yoga on chronic low back pain: a pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10(2):56–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(12):S49–856. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-12-200512200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams KA, Petronis J, Smith D, et al. Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain. 2005;115(1–2):107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groessl EJ, Weingart KR, Aschbacher K, Pada L, Baxi S. Yoga for veterans with chronic low-back pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(9):1123–1129. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tekur P, Singphow C, Nagendra HR, Raghuram N. Effect of short-term intensive yoga program on pain, functional disability and spinal flexibility in chronic low back pain: a randomized control study. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(6):637–644. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou R, Huffman LH American Pain Society; American College of Physicians. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):492–504. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Association of Yoga Therapists. [Accessed September 18, 2009];Yoga and the back. Available at: http://www.iayt.org/site_Vx2/publications/back.pdf.

- 23.Moore J, Lorig K, Von Korff M, Gonzalez VM, Laurent DD. The Back Pain Helpbook. Reading, MA: Da Capo; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritter PL, González VM, Laurent DD, Lorig KR. Measurement of pain using the visual numeric scale. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(3):574–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Von Korff M, Jensen MP, Karoly P. Assessing global pain severity by self-report in clinical and health services research. Spine. 2000;25(24):3140–3151. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, Singer DE, Chapin A, Keller RB. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine. 1995;20(17):1899–1908. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware JE., Jr SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000;25(24):3130–3139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grotle M, Brox JI, Vøllestad NK. Concurrent comparison of responsiveness in pain and functional status measurements used for patients with low back pain. Spine. 2004;29(21):E492–E501. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000143664.02702.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jordan K, Dunn KM, Lewis M, Croft P. A minimal clinically important difference was derived for the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire for low back pain. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Andresen EM, Hadler NM. Race and socioeconomic differences in post-settlement outcomes for African American and Caucasian Workers’ Compensation claimants with low back injuries. Pain. 2005;114(3):462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bombardier C. Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations. Spine. 2000;25(24):3100–3103. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]