Primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast are rare. They were first described by Cubilla and Woodruff in 1977.1 Since then, very few cases have been reported in the literature. We report a new case and discuss the clinical and pathological features of this entity.

Case report

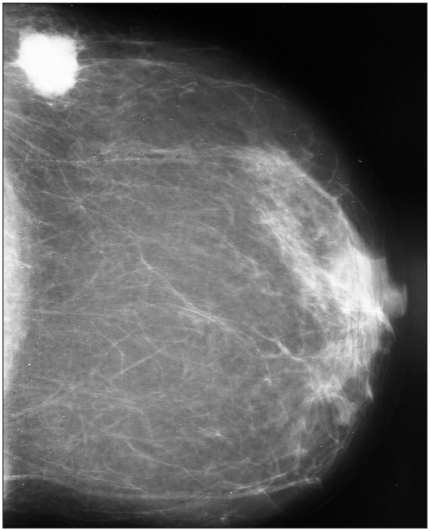

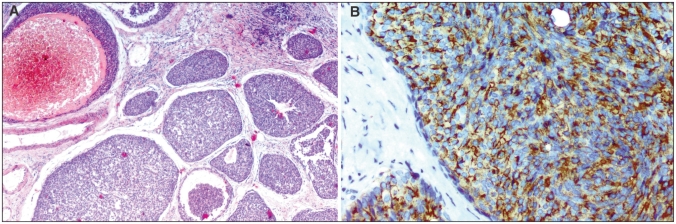

A 64-year-old postmenopausal woman presented with a mass in her left breast. Mammography (Fig. 1) and ultrasonography showed a 3-cm ill-defined mass in the upper outer quadrant of that breast with hypoechoic areas and microlobulated contours. A biopsy specimen of the mass revealed a poorly differentiated carcinoma. The patient underwent a left radical mastectomy with axillary lymph-node dissection. The resected tumour measured 3 × 2 cm and was pale yellow with a relatively smooth border. Histologic examination of the tumour showed areas of invasive carcinoma with solid islands and nests associated with foci of intraductal components. The cells were relatively small and homogeneous, with fine granular basophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. 2A). Mitoses were rare. Immunohistochemical staining revealed diffuse cytoplasmic positivity for chromogranin (Fig. 2B) and synaptophysin, which confirmed the neuroendocrine nature of the tumour. The tumour cells were strongly positive for progesterone and estrogen receptor. To exclude a nonmammary primary site, we examined the head and neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis but found no other abnormalities. The diagnosis was primary solid neuroendocrine carcinoma of the left breast. The patient received adjuvant chemotherapy. There were no signs of recurrence 8 months after the surgical procedure.

Fig. 1.

The mammogram shows an ovoid high-density mass with ill-defined margins in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast.

Fig. 2.

On histologic examination (A) areas of invasive carcinoma with solid islands and nests associated with foci of an intraductal component were seen (hematoxylin–eosin stain; original magnification ×100). (B) Immunohistochemical staining revealed diffuse cytoplasmic positive for chromogranin (original magnification ×200).

Discussion

Primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast were recently recognized as a distinct entity. The World Health Organization defines them as tumours that exhibit morphologic features similar to those of neuroendocrine tumours of both the gastrointestinal tract and lung, and that express neuroendocrine markers in more than 50% of the cell population. These tumours are usually seen in elderly women around the sixth or the seventh decade of life,2 and they have no specific clinical or imaging features.

The histogenesis of neuroendocrine breast tumours is unclear, but they are thought to arise from endocrine differentiation of a breast carcinoma rather than from pre-existing endocrine cells in the breast.3

Morphologically, neuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast include solid neuroendocrine carcinoma, atypical carcinoid, small cell or oat cell carcinoma and large cell neuroenocrine carcinoma. The most helpful features are cellular monotony, nuclear palisading and pseudorosette formation.4 Positive neuroendocrine markers must be found in order to make the diagnosis. The presence of an intraductal component is a helpful criterion to confirm the breast as the origin of a neuroendocrine carcinoma. Moreover, immunostaining for progesterone and estrogen receptor can provide additional evidence for the primary origin of a tumour in the breast.

Histologic grade is the most important predictor of prognosis.5 Solid neuroendocrine carcinoma and atypical carcinoids are considered to be well-differentiated tumours. However, small cell or oat cell carcinoma and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma are poorly differentiated. Hence, we can assert that patients with a solid neuroendocrine carcinoma or an atypical carcinoid have a better prognosis than those with small cell or oat cell carcinoma and with large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Mucinous differentiation and positivity for estrogen and progesterone receptors are also favourable prognostic factors.5 In our case, criteria for good prognosis are the histlogic type of the neuroendocrine tumour and the positivity of chromogranin and synaptophysin receptors. However, since the follow-up period of our patient is only 8 months, we cannot make any conclusions about the prognostis.

Conclusions

Because of the paucity of available literature on primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast, their long-term prognosis and biologic behaviour are not well known. New studies encompassing a larger patient population with long-term follow-up are needed.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Cubilla AL, Woodruff JM. Primary carcinoid tumor of the breast. A report of 8 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1977;1:283–92. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, Sastre-Garau X, et al. Tumours of the breast, neuroendocrine tumours. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2003. pp. 32–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ajisaka H, Maeda K, Miwa A, et al. Breast cancer with endocrine differentiation: report of two cases showing different histologic patterns. Surg Today. 2003;33:909–12. doi: 10.1007/s00595-003-2612-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsang WY, Chan JK. Endocrine ductal carcinoma in situ (E-DCIS) of the breast. Form of low-grade DCIS with distinctive clinicopathologic and biologic characteristics. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:921–43. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199608000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIntire M, Siziopikou K, Patil J, et al. Synchronous metastases to the liver and pancreas from a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the breast diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:54–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]