Abstract

Malignant pheochromocytoma is a rare disease and surgical resection is the only curative treatment. There are no definitive histological or cytological criteria of malignancy, as it is impossible to determine this condition in the absence of advanced locoregional disease or metastases. We report a case of a patient with a giant retroperitoneal tumour, the second largest to be published, which was diagnosed as a malignant pheochromocytoma; it was treated with surgery. The literature is reviewed to evaluate tumour features and criteria to distinguish between benign and malignant pheochromocytomas.

Introduction

Pheochromocytomas are uncommon tumours of great clinical importance because of the catecholamines they secrete. Most pheochromocytomas are benign, and it is almost impossible to differentiate a benign from a malignant tumour only by its histological criteria. Many attempts have been made to find markers that would predict the future behaviour of a non-metastatic pheochromocytoma; these markers include inmunohistochemical markers for growth capacity, angiogenesis and invasion markers (increased expression of Ki-67, p-53, VEGF, heparanase-1, Tenascin, COX-2; decreased expression of inhibin βB, S-100), different cathecolamines values, necrosis, vascular and capsular invasion. However, to date, it is commonly accepted that no single feature is diagnostic of malignant pheochromocytoma without documented metastatic disease.1

Radical surgery is the basis of therapy. Different treatment protocols have also been considered, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormone therapy, with poor results. The survival rate is unknown, due to the few cases reported.

Case report

The patient, a 36-year-old woman without associated disease, was being investigated for lower back pain. An increased density in the left upper quadrant was shown in the abdominal x-ray. Patient evaluation revealed a non-painful, firm and immovable abdominal mass in the epigastrium and left hemiabdomen.

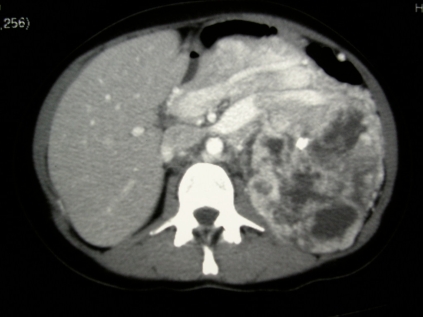

Complete analysis (glucose, ureic acid, plasmatic proteins and ions), including 24-hour urine catecholamines (nor-metanephrine, metanephrine and vanilmandelic acid), and tumour markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen [Ca] 19.9, Ca 125, and β-human chorionic gonadotropin) were normal. No abnormalities were present at red and white blood cells count. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a 17 × 11 × 21 cm mass located in the left retroperitoneum, which occupied a large part of the abdominal cavity. It had a significant aberrant vascularization and displaced the adjacent structures anteriorly. The left kidney was displaced downwards and was infiltrated. The left suprarenal vein contained a thrombus (Fig. 1). The left suprarenal gland could not be identified.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan of the left suprarenal vein thrombus.

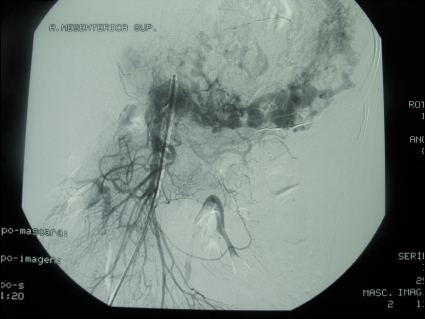

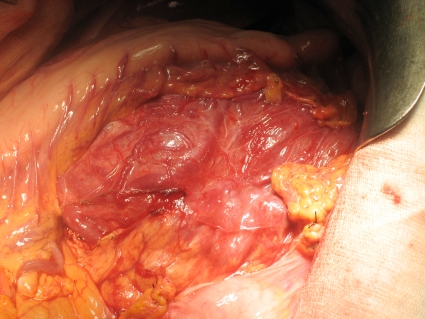

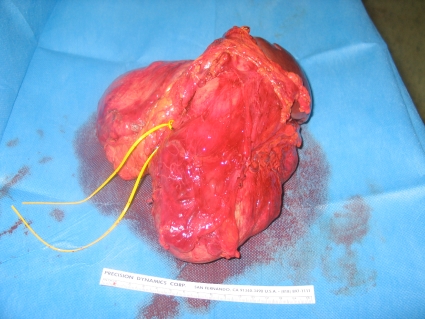

A barium enema and oral endoscopy revealed only an extrinsic compression. Because the origin of the mass was unknown, we performed an exploratory laparotomy. Attempts at preoperative embolization were impossible due to the extensive abnormal vascularization with multiple arteriovenous communications (Fig. 2). A midline xifopubian incision was performed, and a left suprarenal vein thrombectomy (Fig. 3) was necessary along with an en-bloc resection of the mass, left kidney, spleen, and pancreatic body and tail (Fig. 4). No fluctuations in blood pressure appeared intraoperatively, but due to the extent of the resection, the patient remained in the intensive care unit for 48 hours.

Fig. 2.

Arteriography image. Tumour vascularization from the left kidney, superior mesenteric and splenic arteries.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative image where the mass is seen behind the stomach and pancreatic body and tail. Notice the great vascularization.

Fig. 4.

Resection specimen: tumour, spleen, pancreatic body and tail.

Pathologic evaluation revealed a malignant pheochromocytoma with a lone juxtapancreatic lymph node metastasis; the other lymph nodes were normal. The postoperative course was favourable, with normal control CT and normal levels of catecholamines. Due to the absence of residual disease (a positron emission tomography [PET] scan at first month postoperatively was normal), no complementary therapies were needed. There is no evidence of recurrence after 9 months of follow-up. At the present time, the patient is completely asymptomatic, although long-term follow-up with a CT and PET scan and hematologic controls is needed.

Discussion

Pheochromocytoma is an infrequent tumour, originating from the suprarenal medulla and sympathoadrenal neuroendocrine system chromaffin cells. They produce and secrete catecholamines; the triad of headache, sweating and palpitations in patients with hypertension is diagnostic, with a 94% specificity and 91% sensitivity.2

Preoperative diagnosis is usually made by the presence of clinical signs and the determination of catecholamines and their metabolites in blood and urine. Recent studies show a higher sensitivity for the determination of normetanephrine and platelet norepinephrine in 24-hour urine.3 Computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the image techniques initially used in its localization, with a sensitivity between 75% and 100%,4 but a low specificity. In extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma, metastatic and recurrent pheochromocytoma MRI has a higher sensitivity than a CT scan.

The 131I methaiodinebencilguanidin (131-I-MIBG) gam-magraphy, despite its low image quality and definition, has a 83.5% sensitivity and, in combination with platelet normetanephrin, it reaches complete (100%) sensitivity.3,4 A PET scan has a better image resolution and, depending on the tracer (18-fluoro-dihydroxyphenylalanine), its sensitivity could reach 100%.5 Between 8% and 12.5% of pheochromocytomas are malignant,6 with a higher incidence of malignancy in the extra-adrenal location (from 29% to 40%). Preoperative diagnosis of malignancy is impossible in the absence of metastasis or locoregional invasion.

There are studies that try to define variables to determine malignant behaviour, such as the tumour size. According to Sturgeon and colleagues, sizes greater than 6 cm could be a predictor of malignancy.7 However, other authors disagree, such as Wilhelm and colleagues.8 There are few published cases of pheochromocytomas larger than 20 cm; the biggest pheochromocytoma, with a size of 29 × 21 × 12 cm, was presented by Basso and colleagues.9

Currently, malignancy is defined by the existence of metastasis, local recurrence or invasion of adjacent structures. Histological diagnosis of malignancy might be determined by the proliferative activity and the presence of capsular and vascular invasion, although immunochemical techniques, such as such as expression levels of telomerase, are needed.6 These histological features compose the pheochromocytoma adrenal scaled score (PASS), designed by Thompson in 2002 to determine the prognosis of pheochromocytoma.6

Our case is a patient with a large-sized tumour with thrombosis of its drainage vein and suspected organ invasion, suggesting malignancy. There were a large number of mitoses in the pathology evaluation and a metastatic lymph node, which confirmed the diagnosis.

Once the pheochromocytoma is diagnosed, surgery is the treatment of choice. In the presence of metastases, resection can also improve survival and quality of life. Radiation therapy is also a useful option in these cases (mainly in bone metastases). Current chemotherapy combines cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dacarbacine, and it can achieve partial remission and improvement of clinical symptoms in more than half of all cases;5 some patients even experience complete remission. Hormonal blocking with 131-I-MIBG could be useful in residual or irresectable disease.10 Follow-up is also important and, with time, we can determine the malignant tumoural behaviour.

Conclusion

Pheochromocytoma has a good overall prognosis, with a 5-year survival greater than 95% in benign tumours and recurrences below 10%.10 For malignant tumours, due to their low incidence, only isolated cases are published rather than large series, so it is difficult to determine the outcomes.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Zarnegar R, Kebebew E, Duh QY, et al. Malignant pheochromocytoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2006;15:555–71. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodríguez González JM, Parrilla Paricio P, Piñero Madrona A. Sitges-Serra A, Sancho Insenser J. Cirugía Endocrina. Aran: Madrid; 1999. Feocromocitoma; pp. 143–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guller U, Turek J, Eubanks S, et al. Detecting pheochromocytoma. Defining the most sensitive test. Ann Surg. 2006;243:102–7. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000193833.51108.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Goldstein DS. Functional imaging of endocrine tumours: role of positron emission tomography. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:568–80. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann GN, Jeanne ML, Pham P, et al. [11C]Metahydroxyephedrine and [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography Improve Clinical Decision Making in Suspected Pheochromocytome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:187–97. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenhofer G, Bornstein SR, Brouwers FM, et al. Malignant pheochromocytoma: current status and initiatives for future progress. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:423–36. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sturgeon C, Shen WT, Clark OH, et al. Risk assessment in 457 adrenal cortical carcinomas: how much does tumour size predict the likelihood of malignancy? J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:423–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilhelm SM, Prinz RA, Barbu AM, et al. Analysis of large versus small pheochromocytomas: operative approaches and patient outcomes. Surgery. 2006;140:553–60. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basso L, Lepre L, Melillo M, et al. Giant pheochromocytoma: case report. Ir J Med Sci. 1996;165:57–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02942808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reisch N, Peczkowska M, Januszewicz A, et al. Pheochromocytoma: presentation, diagnosis and treatment. J Hypertens. 2006;24:2331–9. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000251887.01885.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]