Abstract

Over the past decade it has become clear that stress can significantly slow wound healing: stressors ranging in magnitude and duration impair healing in humans and animals. For example, in humans, the chronic stress of caregiving as well as the relatively brief stress of academic examinations impedes healing. Similarly, restraint stress slows healing in mice. The interactive effects of glucocorticoids (e.g. cortisol and corticosterone) and proinflammatory cytokines [e.g. interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-lα, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-α] are primary physiological mechanisms underlying the stress and healing connection. The effects of stress on healing have important implications in the context of surgery and naturally occurring wounds, particularly among at-risk and chronically ill populations. In research with clinical populations, greater attention to measurement of health behaviors is needed to better separate behavioral versus direct physiological effects of stress on healing. Recent evidence suggests that interventions designed to reduce stress and its concomitants (e.g., exercise, social support) can prevent stress-induced impairments in healing. Moreover, specific physiological mechanisms are associated with certain types of interventions. In future research, an increased focus on mechanisms will help to more clearly elucidate pathways linking stress and healing processes.

Keywords: Stress, Wound healing, Cytokines, Glucocorticoids, Depression, Anxiety, Psychoneuroimmunology, Psychoimmunology, Neuroimmunology

The skin is the body's largest organ and primary immune defense, preventing bacteria, viruses and other exogenous antigens from entering [1] and limiting the movement of water in and out of the body [2]. As such, the skin's ability to heal wounds quickly and effectively is essential to good health. We now know that stress can slow the rate of wound healing. This has significant implications in the context of surgery and the healing of naturally occurring wounds. Over the past decade, considerable insight has been gained into mechanisms underlying the effects of stress on healing. In the current article, we review the substantial evidence linking stress and wound healing, highlight key physiological mechanisms, and propose innovative directions for future research.

The Wound Healing Process

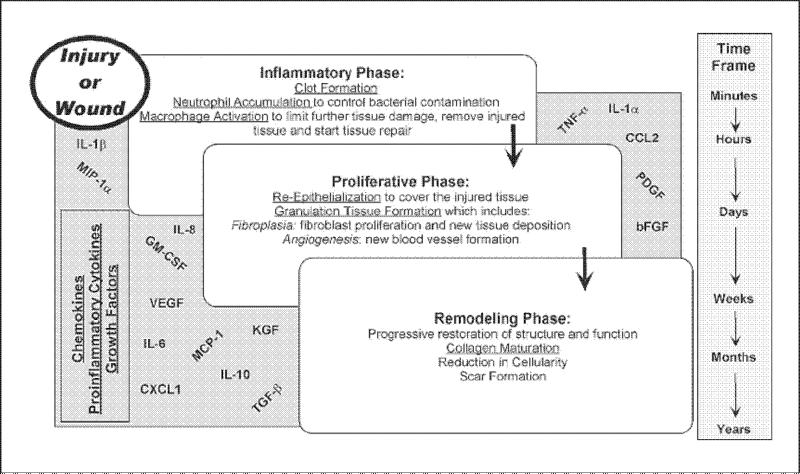

Wound healing is an orderly process initiated in a predictable manner whenever tissue damage occurs. In healthy individuals, healing progresses sequentially through three overlapping phases (fig. 1). There is (1) an inflammatory stage comprised of hemostasis or blood clotting and migration of inflammatory cells to the wound, (2) a proliferative phase involving migration and proliferation of keratinocytes, fibroblasts and endothelial cells, leading to reepithelialization, neovascularization, and granulation tissue formation, and (3) a long remodeling phase involving extracellular matrix maturation aimed at restoring tissue structure and function [3, 4]. Success in later phases is highly dependent on preceding phases. The inflammatory phase begins at the time of initial damage and typically lasts 5–7 days. The factors that initiate inflammation are released by resident cells after traumatic disruption of the intact tissue and the immediate response of platelets to ‘damage’ signals [5]. This initial inflammatory response serves to jump-start healing as inflammation stabilizes the wound by removing contaminating debris and controlling microbial invasion, and then inflammation creates an environment conducive to tissue repair.

Fig. 1.

Stages of wound healing. In healthy individuals, healing progresses sequentially through three overlapping phases: (1) inflammatory phase, (2) proliferative phase, and (3) remodeling phase. Stress can affect progression through these stages via multiple immune and neuroendocrine pathways. The current review focuses on the interactive role of glucocorticoids and cytokines (e.g. IL-8, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10). However, additional cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors are important to healing. These include CXC chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), CC chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protien-1 alpha (MIP-lα), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor-β (TNF-β), keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) [for a broader review of physiological mechanisms relevant to wound healing, please see 73].

The inflammatory phase encompasses three critical elements that require the recruitment of cells from circulation: (1) passive aggregation of platelets for hemostasis, (2) neutrophil influx for infection control, and (3) macrophage accumulation to initiate repair [6, 7]. The neutrophils and monocytes are attracted into injured tissues concurrently, but neutrophils predominate due to their abundance in the circulation. Both cell populations are recruited to the wound by a myriad of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines arising from the blood clot and injured cells at the margins of the wound. Among their many functions, these cells are phagocytic and remove bacteria from the wound [3].

In addition, newly recruited monocytes, which differentiate into macrophages once they enter the tissue parenchyma, begin to initiate tissue repair. For example, macrophages produce enzymes such as hyaluronidase, elastase, and collagenase, which degrade hyaluronic acid, elastin and collagen in connective tissue [8, 9]. In doing so, the macrophage weakens the extracellular matrix to allow for migration and in-growth of fibroblasts, keratinocytes and endothelial cells that build the new tissue during the subsequent or proliferative phase of healing. Not only do the macrophages prepare the extracellular matrix for tissue growth, they also synthesize and release multiple growth and regulatory factors, critical to the coordination of new tissue formation. Once macrophages begin to produce these growth factors, the repair part of healing actually begins. Infact, the formation of new capillaries from preexisting blood vessels (angiogenesis) and the deposition of new extracellular matrix by tissue fibroblasts are characteristic of the proliferative phase of repair. Once new tissue has been built to fill the void left by the initial injury, the final stage of healing begins. It involves contraction and tissue remodeling and is important for the approximate restoration of the original tissue's structure and function. Whereas the first two stages of repair can be completed in as little as 12-14 days, this last phase of healing may continue for weeks, months or even years after injury.

Although healing is a consistent and regulated process, stress can affect its progression via multiple immune and neuroendocrine pathways. For one, proinflammatory cytokines are key to successful healing. Neutrophils and macrophages are major sources of proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-lα (IL-1α), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). These cytokines help to prevent infection, prepare injured tissue for repair, and enhance recruitment and activation of additional phagocytic cells [10]. In addition, cytokines regulate the ability of fibroblasts and epithelial cells to remodel damaged tissue [10]. Therefore, proinflammatory cytokines play a critical role in the healing cascade. Demonstrating this, IL-6-deficient mice exhibit up to a 3-fold greater healing time as compared to healthy wild-type mice [11].

The effects of stress on glucocorticoid function are another key-related mechanism in the stress-healing association. Glucocorticoids, which are responsive to stress, affect inflammatory processes. For example, stress-induced elevations in glucocorticoids can transiently suppress both IL-1 and TNF production in humans [12]. Similarly, mice treated with glucocorticoids showed impairment in the induction of IL-1 and TNF, as well as deficient wound repair [13]. Although other mechanisms are implicated in the link between stress and healing, the current review focuses on the substantial evidence for the interactive roles of proinflammatory cytokines and glucocorticoid hormones.

Stress and Healing: Experimental Methods, Effects, and Mechanisms

The first human study to link stress and healing examined the effects of the chronic stress of caregiving for a loved one with Alzheimer's disease or other dementia. Multiple studies have demonstrated that caregiving is associated with significant immune dysregulation [14–16]. Consistent with these findings, women caregivers took 9 days, or 24% longer to heal a small standardized punch biopsy wound than did well-matched controls [17]. Healing rate was determined using photographs to compare wound size to a standard dot. In the same study, data revealed that circulating peripheral blood leukocytes from caregivers expressed less IL-1β in mRNA in response to lipopolysaccharide stimulation than did cells from controls [17]. IL-1β is a key cytokine produced in response to tissue damage; therefore, a strong IL-1β response is desirable in the context of healing.

Milder stress also impairs healing. In a sample of 11 dental students, mucosal punch biopsy wounds placed in the hard palate healed an average of 40% more slowly during an examination period than during avacation period, which was rated as subjectively less stressful by participants [18]. This effect was remarkably reliable: every student in the study healed more slowly during exams than duringvacation. In addition, consistent with studies on caregiving stress, production of IL-1β by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated peripheral blood leukocytes was reduced in every student during the examination period as compared to vacation.

Later research examined cytokine production at the local wound site. In a study of 36 women, blister wounds were created using a suction blister device that produced 8 sterile 8-mm blister wounds [19]. A plastic template with 8 wells was placed over the blister wounds and each well was filled with the woman's serum and a salt solution, resulting in the migration of cells into the blister chambers. Women reporting greater stress had significantly lower levels of two key cytokines, IL-α and IL-8, at the wound site [19]. By demonstrating an association between stress and cytokine production at the local wound site, this study significantly extended previous data linking stress and mechanisms associated with healing.

Recent data show that even a single half-hour marital conflict discussion in a laboratory setting can slow wound healing: married couples healed standardized blister wounds more slowly after a conflictive interaction than after a supportive interaction [20]. Decreased production of three key cytokines – IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α – was observed at the wound site following conflict as compared to a supportive interaction; these local cytokine changes were observed in concordance with slower healing. Furthermore, couples who demonstrated consistently high levels of hostile behavior during both conflictive and supportive interactions healed wounds at 60% of the rate of low hostile couples [20]. This study demonstrated effects of both an acute stressor and a pattern of behavior on wound healing. These findings are consistent with a large literature demonstrating the impact of marital conflict on immune function [21–23].

Other research has examined relationships between wound healing and stress. Among healthy males, greater perceived stress 2 weeks before and on the day of getting a punch biopsy wound predicted slower healing from 7 to 21 days postwounding [24]. Healing was also significantly related to cortisol levels: greater morning increases in cortisol predicted slower healing [24]. Healing in this study was assessed with ultrasound biomicroscopy, a relatively new imaging technique that utilizes high-resolution ultrasound scanning to measure wound depth as well as circumference. This approach provided an assessment of healing in deep tissue layers and enabled measurement of wound circumference not impeded by scab formation [25].

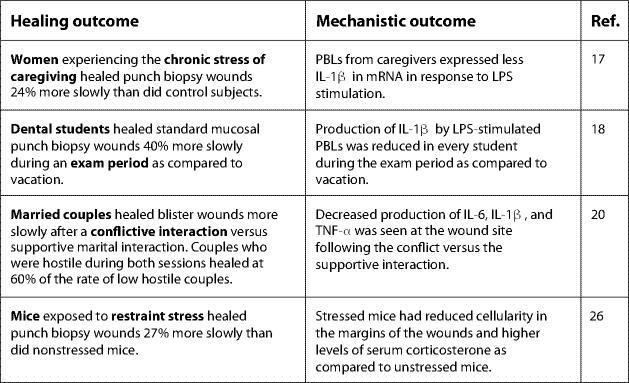

Together, data from human studies demonstrate that stressors of varied magnitude and duration can significantly slow healing (fig. 2). The effect of examination stress on wound healing is particularly notable given that the participants in those studies had a great deal of experience and success in taking examinations. Similarly, having a conflictual discussion is a very common experience. Therefore, other types of relatively predictable, transient, and commonplace stressors may have comparable effects.

Fig. 2.

Key findings linking stress and wound healing. PBLs = Peripheral blood leukocytes; LPS = lipopolysaccharide.

Animal models support and extend findings related to causal mechanisms linking stress and healing (fig. 2). For example, mice exposed to repeated restraint stress prior to and after wounding healed punch biopsy wounds 27% more slowly than did their nonstressed counterparts [26]. The stress-induced delay in healing was consequential as the delay in healing correlated with an increased susceptibility to infection with opportunistic microorganisms. Specifically, mice subjected to restraint stress for 3 days prior to punch biopsy wounding exhibited 2–5 times greater bacterial growth (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus) at the wound site compared to their nonstressed counterparts [27]. Compounding the influence of stress, infected wounds heal more slowly and are more likely to result in scarring [28].

The effect of stress in this animal model manifested itself early in the inflammatory phase of the healing process: mice exposed to restraint stress had reduced cellularity in the margins of the punch biopsy wounds, particularly early in the healing process [26]. As described above, a key function of the inflammatory phase of healing is the recruitment of cells which clear bacteria and other foreign substances from the wound site [3]. If the neutrophils are not recruited to the wound in adequate numbers, bacteria may grow unchecked. Likewise, if monocytes/macrophages do not accumulate in the wound, the enzymes and growth factors essential to new tissue deposition may not be produced. Consequently, the wound can become contaminated and heal more slowly, which was the case in the mouse study described above.

Mice subjected to restraint stress also had significantly higher levels of serum corticosterone as compared to unstressed controls. The elevation in serum corticosterone was found important for the delay in healing and the increased incidence of infection because when the stressed animals were treated with a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist (RU40555), their healing rates were equivalent to nonstressed animals [26]. These results demonstrated that the suppressive effect of glucocorticoids on inflammatory activity at the wound site was a key factor linking stress and healing.

Further solidifying this link, data show that stress reduced the expression of genes that initiate the inflammatory phase of repair (i.e., IL-1 and TNF) [29, 30]. Low expression of the genes for these inflammatory substances within the wound may not be sufficient to recruit enough inflammatory cells during the early response to injury, which may also affect the expression of other mediators necessary for subsequent cellular infiltration and tissue repair. Again, treatment of stressed animals with glucocorticoid receptor antagonists restored the expression of many of the genes that are involved in inflammation. Therefore, studies in mouse models indicate that by affecting the inflammatory phase of wound repair, stress-induced glucocorticoid hormones reduce the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the wound margin, impair antibacterial function, and slow healing.

Stress and Healing in Naturalistic Settings

Stress can also invoke measurable effects on healing outside of a controlled laboratory setting. For example, among elderly men and women, greater anxiety and depression predicted slower healing of naturally occurring leg ulcers [31]. Specifically, patients reporting greater than average symptoms of depression or anxiety were 4 times more likely to be categorized as slow healers compared to patients reporting less distress. Although potential behavioral or physiological mediators were not assessed in this study, results are consistent with previous research.

Studies of surgical recovery also shed light on the effects of stress on healing. In a sample of adults undergoing hernia surgery, self-reported worry about surgery predicted slower healing time, after controlling for age, gender, and type of anesthetic [32]. Moreover, greater preoperative stress predicted lower levels of IL-1 in the wound fluid, while greater worry about surgery was related to lower matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in the wound fluid [32]. This is consistent with previous evidence that nervous system activation can modulate MMP expression [33]. MMP-9, which is regulated by cytokines IL-1 and IL-6, facilitates cellular migration within the wound area and thus aids in tissue remodeling [34].

Effects of stress on wound healing and surgical recovery may be compounded by effects of physical pain, a common symptom of both laboratory wounding and surgery [35]. For example, in a study of women undergoing elective surgery, those experiencing greater postsurgical pain took longer to heal a laboratory-induced punch biopsy wound [36]. The immune dysregulating effects of surgery – including suppression of lymphocyte proliferative responsiveness and increases in proinflammatory cytokine responses – can be attenuated by appropriate analgesic treatment [37]. However, pain medication treatments in the absence of pain can be immune suppressive [38, 39], lending support to the contention that pain specifically is related to wound healing. A physical and psychological stressor itself, pain can also be enhanced by other stressors [40, 41]. Thus, individuals experiencing pain as well as other stress may be at greatest risk for slower healing.

Stress and Skin Barrier Repair

Relevant to wound healing, effects of stress on skin function have also been examined using the less invasive technique of tape stripping to examine skin barrier repair. Through repeated applications of cellophane tape, commonly to the forearm in humans, a layer of skin cells is removed causing mild skin barrier disruption. When disturbed by processes such as tape stripping or chemical solvent damage, the skin allows greater transepidermal water loss [2]. Transepidermal water loss can be measured using an evaporimeter [42] with multiple assessments allowing for the tracking of barrier recovery over time.

Using such procedures, Garg et al. [43] assessed skin barrier recovery among a group of professional students at three sequential time points: the end of winter vacation, during final exams, and at the end of spring vacation. Paralleling findings from Marucha et al. [18], students experienced significantly slower skin barrier recovery during the examination period than during either vacation period [43]. This effect was the greatest in students reporting the most stress. A strength of this study was the assessment of healing during two vacation periods; these findings demonstrated that the effects of relatively brief stress can be alleviated when the stressor is removed.

Stressors of an even shorter duration than academic examinations can also affect skin barrier recovery. Among healthy women, a modified Trier Social Stress Test, in which participants complete speech and math tasks under conditions of social evaluation [44], resulted in slower recovery of skin barrier function following tape stripping [45]. This social stressor also caused significant increases in cortisol as well as increases in circulating IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-10. It should be noted that cytokines serve multiple functions, and circulating versus local production of cytokines have different implications for health. Indeed, although a robust inflammatory response at the site of a wound is beneficial, high levels of circulating inflammatory markers are associated with impaired healing.

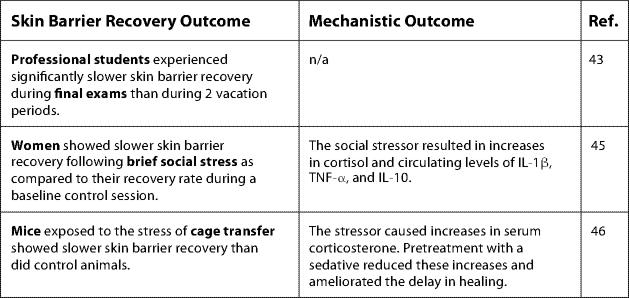

Supporting findings in humans, exposure to the stress of cage transfer resulted in slower healing following tape stripping in mice [46]. As in the study by Padgett et al. [26], these mice demonstrated marked increases in corticosterone after experiencing the stressor. Administration of a sedative before transfer reduced the rise in serum corticosterone and ameliorated the delay in barrier recovery. Moreover, systemic administration of corticosterone in the absence of a stressor also delayed barrier recovery, an effect that was reversed by administration of a glucocorticoid antagonist [46]. Therefore, results from studies of skin barrier repair parallel findings of the effects of stress on wound healing, and provide evidence for a similar mechanistic role of glucocorticoids (fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Key findings linking stress and skin barrier recovery. n/a = Not available.

Health Behaviors

Health behaviors – including diet, sleep, exercise, smoking, and alcohol use – comprise another key pathway from stress to wound healing. Heightened distress is associated with less adaptive health behavior, including smoking, poorer diet, and less sleep [47, 48]. Although existing evidence suggests that health behaviors do not fully account for the effects of stress on wound healing, they may partly explain or exacerbate the effects of stress [24]. Therefore, assessment of health behaviors is an important, though frequently omitted, component of research linking stress and healing.

Sleep is one important factor: Severe sleep disruption can impair healing. In a sample of 25 women, exposure to 48 h of sleep deprivation resulted in dysregulated circulating cytokine levels and delayed skin barrier recovery after tape stripping [45]. Even relatively mild sleep disruption, common during stress, can alter proinflammatory cytokine profiles as well as growth hormone (GH) secretion [49–51]. GH enhances healing through several functions including stimulating monocyte migration, enhancing macrophage activation, and amplifying bacterial killing by macrophages [52]. Because the majority of GH release occurs during sleep [53], stress can substantially affect GH production by altering sleep architecture.

The wound healing process is also highly dependent on nutritional intake: low intake of glucose, polyunsaturated fatty acids, protein, and certain vitamins may all negatively affect wound healing [54, 55]. Heavy alcohol use also appears to slow wound healing, via a number of routes. In addition to nutritional deficits common among heavy alcohol users, alcohol can retard wound healing by contributing to cardiac and immune dysfunction as well as to delays in cell migration and deposition of collagen at the wound site [56, 57].

Smokers heal wounds (both naturally occurring and those following surgery) more slowly than nonsmokers [58]. This appears to be due at least in part to the effects of nicotine and other toxins in cigarette smoke, which exert effects known to impair wound healing, such as reduced proliferation of macrophages and a decrease in levels of oxygen capable of reaching the periphery [58]. Physical activity level is another important consideration: indeed, exercise may be an effective mode of intervention [59], as discussed below. The effects of stress on behavioral factors are often compounded; depressed or anxious individuals are more likely to abuse drugs and less likely to exercise and have a well-balanced diet, while unhealthy behaviors can potentiate psychological distress [60].

Interventions for Enhancing Wound Healing

A variety of interventions have been used to target stress or the effects of stress with the goal of improving healing. For one, exercise influences immune and endocrine function as well as psychological responses to stress. Recent data demonstrate that regular physical activity can speed healing. Short-term exercise (1 h/day for 3 days) did not affect rate of wound healing in a sample of 10 women [45]. However, older adults who completed a 4-week exercise intervention (1 h/day for 3 days/week) healed standard punch biopsy wounds 25% more quickly than did their less active counterparts [59]. Notably, these effects were found despite low self-reported stress across the sample; effects may be even greater among individuals reporting more distress.

Social contact may also buffer the effects of stress on healing. Among hamsters subjected to restraint stress, those who were pair-housed had significantly lower serum cortisol concentrations than did those who were socially isolated [61]. This reduction in cortisol had an impressive influence on wound repair: there were no significant differences in healing between pair-housed animals subjected to restraint stress and those maintained under nonstressful conditions. In part, the protective effects of social housing appeared to be mediated by oxytocin, a hormone released during social contact that facilitates social bonding. The administration of an oxytocin antagonist to socially housed animals delayed healing [61]. Moreover, treatment of socially isolated animals with oxytocin attenuated stress-induced cortisol increases and speeded healing [61]. These data are consistent with a large body of literature demonstrating health benefits of social support in humans [23, 62] and suggest a promising area of future research: the effects of social support on healing among patient populations.

In addition to its effects on serum cortisol/corticosterone, stress also induces substantial tissue hypoxia in the wound. As oxygen is necessary for healing [63, 64], oxygen therapy may also prevent negative effects of stress on wound healing. Although wounding itself is associated with tissue hypoxia (normal tissue pO2 ≈ 60 mm Hg; wound pO2 ≈ 10–60 mm Hg) and hypoxia is thought to be important for healing (e.g. angiogenesis) [65, 66], stress drives tissue oxygen levels to a lower level where healing is impaired (stressed wound pO2 ≈ <10 mm Hg). Therefore, increased oxygen demand and decreased oxygen supply at the site of the wound during times of stress may be a mechanism underlying the stress-healing association. In support of this hypothesis, restraint-stressed mice exposed to hyperbaric oxygen therapy twice per day during the first 5 days of healing healed at a rate nearly equal to unstressed mice [67]. Oxygen appeared to improve wound healing via its attenuating effects on inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression [67].

Future Directions

As described, glucocorticoids and proinflammatory cytokines are two primary pathways by which stress affects healing. However, other mechanisms are also implicated. Greater exploration of the role of glucocorticoids, GH, oxytocin, and other hormones/growth factors will provide a clearer understanding of the multiple biological pathways by which stress affects healing. Similarly, we know that the nerve fibers in a tissue have a substantial influence on healing as illustrated by the observation that denervation substantially reduces wound closure [68]. However, little attention has been paid to delineating the influences of stress on the nerves in an injured tissue. It would be no surprise to discover that their neuropeptides and neurotransmitters play an important role in the stress-healing link.

In addition, greater attention to the effects of health behaviors is imperative for human studies. The true impact of stress on wound healing through physiological mediators cannot be determined without accounting more adequately for the role of behavior. This is particularly true among patient populations. Moreover, because behavior is more easily modifiable than other factors related to wound healing, it has been and will continue to be a key target of intervention.

Importantly, the effects of stress on health outcomes in general and immune outcomes more specifically may not be equal throughout the life span [69]. For example, in terms of wound healing, older adults evidence slower healing and greater risk of wound infection [70]. Understanding both the unique and interactive effects of stress and aging will be useful in targeting intervention efforts.

Another important area for exploration is stress and healing in the context of diabetes, a condition characterized by both chronic inflammation [71], and impaired wound healing. Diabetes affected nearly 8% of the US population in 2001 [72]; the prevalence is expected to increase exponentially in the coming years due to the growing obesity epidemic and an aging population. Therefore, research on the effects of stress on wound healing within this population is of clear clinical relevance.

In the past decade, research in the area of stress and healing has grown significantly. Concordant findings from animal and human models using a variety of stress paradigms, wounding techniques, and methods of healing assessment have now clearly established that stress slows healing. Dysregulation of both glucocorticoid and cytokine function are key biological links between stress and healing. However, further elucidation of these and other neuroendocrine and immune mechanisms is needed. The potential clinical impact of stress on wound healing is notable, with important implications in the context of surgery and naturally occurring wounds. As research with clinical populations continues, increased emphasis on assessment of behavioral factors is critical. Moreover, a continuing emphasis on physiological mechanisms underlying successful interventions will best inform future efforts.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NIH Training Grant T32 AI55411, NIH grants AT002971 and AG025732, NIH General Clinical Research Center Grant M01-RR-0034, and Comprehensive Cancer Center Grant CA16058.

References

- 1.Elias PM. Stratum corneum defensive functions: an integrated view. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:183–200. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks R. The stratum corneum barrier: the final frontier. J Nutr. 2004;134:2071S–2021S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.8.2017S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baum CL, Arpey CJ. Normal cutaneous wound healing: clinical correlation with cellular and molecular events. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:674–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King SM, Reed GL. Development of platelet secretary granules. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s1084952102000599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart J. Inflammation. 1. Its role in the healing of acute wounds. J Wound Care. 2002;11:205–209. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2002.11.6.26411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henry G, Garner WL. Inflammatory mediators in wound healing. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:483–507. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(02)00200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hieta N, Impola U, Lopez-Otin C, Saarialho-Kere U, Kahari VM. Matrix metalloproteinase-19 expression in dermal wounds and by fibroblasts in culture. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:997–1004. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madlener M, Parks WC, Werner S. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their physiological inhibitors (TIMPs) are differentially expressed during excisional skin wound repair. Exp Cell Res. 1998;242:201–210. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowry SF. Cytokine mediators of immunity and inflammation. Arch Surg. 1993;28:1235–1241. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420230063010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallucci RM, Simeonova PP, Matheson JM, Kommineni C, Guriel JL, Sugawara T, Luster MI. Impaired cutaneous wound healing in interleukin-6-deficient and immunosuppressed mice. FASEB J. 2000;14:2525–2531. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0073com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeRijk R, Michelson D, Karp B, Petrides J, Galliven E, Deuster P, Paciotti G, Gold PW, Sternberg EM. Exercise and circadian rhythm-induced variations in plasma cortisol differentially regulate interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) production in humans: high sensitivity of TNF-α and resistance of IL-6. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2182–2192. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.7.4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hübner G, Brauchle M, Smola H, Madlener M, Fassler R, Werner S. Differential regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines during wound healing in normal and glucocorticoid-treated mice. Cytokine. 1996;8:548–556. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1996.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esterling BA, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Psychosocial modulation of cytokine-induced natural killer cell activity in older adults. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:264–272. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199605000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser R, Sheridan JF, Malarkey WB, MacCallum RC, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Chronic stress modulates the immune response to a pneumococcal pneumonia vaccine. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:804–807. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200011000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, Malarkey WB, Sheridan J. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3043–3047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Marucha PT, Malarkey WB, Mercado AM, Glaser R. Slowing of wound healing by psychological stress. Lancet. 1995;346:1194–1196. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marucha PT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Favagehi M. Mucosal wound healing is impaired by examination stress. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:362–365. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Marucha PT, MacCallum RC, Laskowski BF, Malarkey WB. Stress-related changes in proinflammatory cytokine production in wounds. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:450–456. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Loving TJ, Stowell JR, Malarkey WB, Lemeshow S, Dickinson SL, Glaser R. Hostile marital interactions, proinflammatory cytokine production, and wound healing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1377–1384. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton T. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham JE, Christian LM, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Marriage, health, and immune function: a review of key findings and the role of depression. In: Beach S, Wambolt M, editors. Relational Processes and DSM-V: Neuroscience, Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment. American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington: 2006. pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham JE, Christian LM, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Close relationships and immunity. In: Ader R, editor. Psychoneuroimmunology. Elsevier Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2006. pp. 781–798. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebrecht M, Hextall J, Kirtley L-G, Taylor A, Dyson M, Weinman J. Perceived stress and cortisol levels predict speed of wound healing in healthy male adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:798–809. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dyson M, Moodley S, Verjee L, Verling W, Wienman J, Wilson P. Wound healing assessment using 20 MHz ultrasound and photography. Skin Res Technol. 2003;9:116–121. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0846.2003.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padgett DA, Marucha PT, Sheridan JF. Restraint stress slows cutaneous wound healing in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 1998;12:64–73. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1997.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rojas I, Padgett DA, Sheridan JF, Marucha PT. Stress-induced susceptibility to bacterial infection during cutaneous wound healing. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:74–84. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2000.0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robson MC. Wound infection: a failure of wound healing caused by an imbalance of bacteria. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:637–650. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70572-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercado AM, Padgett DA, Sheridan JF, Marucha PT. Altered kinetics of IL-1 alpha, IL-1 beta, and KGF-1 gene expression in early wounds of restrained mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:150–162. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mercado AM, Quan N, Padgett DA, Sheridan JF, Marucha PT. Restraint stress alters the expression of interleukin-1 and keratinocyte growth factor at the wound site: an in situ hybridization study. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;129:74–83. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole-King A, Harding KG. Psychological factors and delayed healing in chronic wounds. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:216–220. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Alley PG, Booth RJ. Psychological stress impairs early wound repair following surgery. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:865–869. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088589.92699.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang EV, Bane CM, MacCallum RC, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Malarkey WB, Glaser R. Stress-related modulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;133:144–150. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pajulo OT, Pulkki KJ, Alanen MS, Reunanen MS, Lertola KK, Mattila-Vuori AI, Viljanto JA. Correlation between interleukin-6 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in early wound healing in children. Wound Repair Regen. 1999;7:453–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.1999.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Page GG, Marucha PT, MacCallum RC, Glaser R. Psychological influences on surgical recovery: perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Am Psychol. 1998;53:1209–1218. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.11.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGuire L, Heffner KL, Glaser R, Needleman B, Malarkey WB, Dickinson S, Lemeshow S, Cook C, Muscarella P, Melvin S, Ellison C, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Pain and wound healing in surgical patients. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:165–172. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3102_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beilin B, Shavit Y, Trabekin E, Mordashev B, Mayburd E, Zeidel A, Bessler H. The effects of postoperative pain management on immune response to surgery. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:822–827. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000078586.82810.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Page GG, Blakely WP, Ben-Eliyahu S. Evidence that postoperative pain is a mediator of the tumor-promoting effects of surgery in rats. Pain. 2001;90:191–199. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Page GG. Surgery-induced immunosuppression and postoperative pain management. AACN Clin Issues Crit Care Nurs. 2005;16:302–309. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200507000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melzack R, Katz J. The gate control theory: reaching for the brain. In: Hadjistavropoulos T, Craig KD, editors. Pain: Psychological Perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graham JE, Robles TF, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Malarkey WB, Bissell MG, Glaser R. Hostility and pain are related to inflammation in older adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pinnagoda J, Tupker RA, Agner T, Serup J. Guidelines for transepidermal water loss (TEWL) measurement. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:164–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1990.tb01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garg A, Chren MM, Sands LP, Matsui MS, Marenus KD, Feingold KR, Elias PM. Psychological stress perturbs epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis: implications for the pathogenesis of stress-associated skin disorders. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:53–59. doi: 10.1001/archderm.137.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH. The ‘trier social stress test’ — a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;28:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Altemus M, Rao B, Dhabhar FS, Ding W, Granstein RD. Stress-induced changes in skin barrier function in healthy women. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:309–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Denda M, Tsuchiya T, Elias PM, Feingold KR. Stress alters cutaneous permeability barrier homeostasis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R367–R372. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.2.R367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steptoe A, Wardle J, Pollard TM, Canaan L, Davies GJ. Stress, social support and health-related behavior: a study of smoking, alcohol consumption and physical exercise. J Psychosom Res. 1996;41:171–180. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(96)00095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vitaliano PP, Scanlan JM, Zhang J, Savage MV, Hirsch IB. A path model of chronic stress, the metabolic syndrome, and coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:418–435. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leproult R, Copinschi G, Buxton O, Van Cauter E. Sleep loss results in an elevation of cortisol levels the next evening. Sleep. 1997;20:865–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vgontzas AN, Papanicolaou DA, Bixler EO, Lotsikas A, Zachman K, Kales A, Prolo P, Wong ML, Licinio J, Gold PW, Hermida RC, Mastorakos G, Chrousos GP. Circadian interleukin-6 secretion and quantity and depth of sleep. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2603–2607. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.8.5894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Irwin M. Effects of sleep and sleep loss on immunity and cytokines. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:503–512. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zwilling BS. Neuroimmunomodulation of macrophage function. In: Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, editors. Handbook of Human Stress and Immunity. Academic Press; San Diego: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Veldhuis JD, Iranmanesch A. Physiological regulation of the human growth hormone (GH)-insulin-like growth factor type I (IGF-I) axis: predominant impact of age, obesity, gonadal function, and sleep. Sleep. 1996;19:S221–224. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.suppl_10.s221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Russell L. The importance of patients’ nutritional status in wound healing. Br J Nurs. 2001;10:S42–49. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2001.10.Sup1.5336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Posthauer ME. The role of nutrition in wound care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2006;19:43–52. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200601000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:606–617. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.5.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benveniste K, Thut P. The effect of chronic alcoholism on wound healing. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1981;166:568–575. doi: 10.3181/00379727-166-41110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Silverstein P. Smoking and wound healing. Am J Med. 1992;93:22S–24S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90623-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Emery CF, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Frid DJ. Exercise accelerates wound healing among healthy older adults: a preliminary investigation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1432–1436. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.11.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grunberg NE, Baum A. Biological commonalities of stress and substance abuse. In: Shiffman S, Wills TA, editors. Coping and Substance Use. Academic Press; San Diego: 1985. pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Detillion CE, Craft TKS, Glasper ER, Prendergast BJ, DeVries AC. Social facilitation of wound healing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. 2004;59:676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sen CK, Khanna S, Gordillo G, Bagchi D, Bagchi M, Roy S. Oxygen, oxidants, and antioxidants in wound healing. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;957:239–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gordillo GM, Sen CK. Revisiting the essential role of oxygen in wound healing. Am J Surg. 2003;186:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Albina JE, Reichner JS. Oxygen and the regulation of gene expression in wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2003;11:445–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2003.11619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elson DA, Ryan HE, Snow JW, Johnson R, Arbeit JM. Coordinate up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-lalpha and HIF-1 target genes during multi-stage epidermal carcinogenesis and wound healing. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6189–6195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gajendrareddy PK, Sen CK, Horan MP, Marucha PT. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy ameliorates stress-impaired dermal wound healing. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith PG, Liu M. Impaired cutaneous wound healing after sensory denervation in developing rats: effects on cell proliferation and apoptosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;307:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s00441-001-0477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Graham JE, Christian LM, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress, age, and immune function: toward a lifespan approach. J Behav Med. 2006;29:389–400. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghadially R, Brown B, Sequeira-Martin S, Feingold K, Elias PM. The aged epidermal permeability barrier: structural, functional, and lipid biochemical abnormalities in humans and a senescent murine model. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2281–2290. doi: 10.1172/JCI117919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1111–1119. doi: 10.1172/JCI25102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Werner S, Grose R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:835–870. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2003.83.3.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]