To the Editor: Infections are the most frequent and serious wound complications in injection drug users (IDUs). Wound botulism is primarily caused by Clostridium botulinum (1) and was first observed in IDUs in New York in 1982 (2). It results from the introduction of C. botulinum spores into a wound and their multiplication, germination, in situ synthesis, and secretion of toxin under anaerobic conditions. Of 7 designated toxin types, neurotoxins A, B, E, and F result in human disease. During the 1990s, wound botulism cases among IDUs increased in the United States in conjunction with the use of black-tar heroin (3). Since 2000, wound botulism cases in IDUs have been reported in Europe (4). To our knowledge, molecular epidemiologic analyses have not been performed to confirm suspected outbreaks.

Within a 6-week period in October and November 2005, 12 clinical cases were recognized in the metropolitan area of Cologne, Germany (5). Six patients were successfully treated at teaching hospitals of the University of Cologne. On admission, all socially nonrelated patients had signs of bilateral symmetric cranial neuropathies such as ptosis, diplopia, blurred vision, dysphagia, dysarthria associated with symmetrical descending weakness of the upper extremities, and no sensory deficiencies. Treatment of patients included administration of trivalent A, B, and E antitoxin; antimicrobial drugs such as penicillin G or mezlocillin with metronidazole; and surgical drainage of any existing abscesses.

Patient 1, a 31-year-old female IDU, had multiple abscesses on both legs. Four days after her admission, wound botulism was suspected and antitoxin administered. Respiratory failure required mechanical ventilation for 11 weeks. Patient 2, a 51-year-old male IDU, had 1 large abscess on the left lower leg. Antitoxin was administered within 3 days of hospital admission. Mechanical ventilation was required for 5 weeks. Patient 3, a 25-year-old male IDU, had a large abscess on the left forearm. Patient 4, a 43-year-old man who used heroin intramuscularly, had an abscess of moderate size on the left forearm. Antitoxin was administered within 12 hours of admission to patients 3 and 4, and both patients required 2 weeks of respiratory support. Patient 5, a 32-year-old male IDU who was positive for hepatitis C virus, had purchased heroin from the same dealer as patient 2. Abscesses were absent. Antitoxin was administered within several hours of admission. Within 10 days, the patient recovered fully without need for mechanical ventilation. Patient 6, a 44-year-old male IDU, had several skin lesions at injection sites on his arms, but no abscesses. He received antitoxin treatment within several hours of admission and was discharged with minimal residual neck weakness after 7 days.

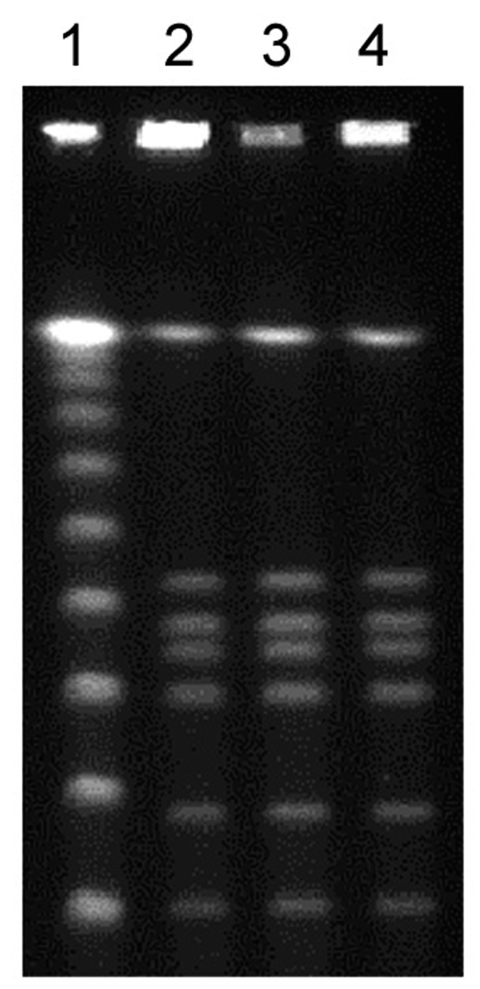

Serum specimens were obtained from patients 1, 2, 5, and 6. Botulinum toxin detected by the mouse bioassay in serum of patients 1 and 2, but not of patients 5 and 6, was neutralized by polyvalent antitoxin (Novartis Behring, Marburg, Germany). Abscess specimens were available from patients 2, 3, and 4. Anaerobic cultures grew C. botulinum, which was identified by Gram stain, culture morphologic features, Rapid ID 32A (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), and 16S rDNA sequencing. All strains were susceptible to penicillin G and metronidazole, as determined by the E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). PCR assays performed for C. botulinum type A, B, E, and F neurotoxin genes (6,7) identified the single toxin B. Toxin B production was confirmed by the mouse bioassay. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) after SmaI, SacII, and XhoI restriction (8) showed indistinguishable strains from patients 2, 3, and 4 (shown for SmaI in the Figure).

Figure.

Fingerprint patterns obtained for Clostridium botulinum isolates following pulsed-field gel electrophoresis after SmaI restriction show identical strains. Lane 1, 100-bp ladder; lanes 2–4, abscess fluid isolates from patients 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

To our knowledge, this is the first outbreak of wound botulism in IDUs that was confirmed by molecular epidemiologic typing. PFGE suggests a single-source exposure with C. botulinum type B in at least 3 IDUs; this implies that the heroin was obtained from a common source, where contamination with C. botulinum spores may have been introduced when mixed with adulterants or diluted with substances such as dextrose or dyed paper. Skin popping (subcutaneous and intramuscular injection), which may increase the odds of wound botulism by a factor >15 (9), was used by all patients for drug delivery. This study confirms previous observations that the duration of clinical symptoms before antitoxin administration affects the need for and duration of mechanical ventilation (10). Here, the time from hospital admission to antitoxin treatment ranged from several hours to 4 days and correlated with the mechanical ventilation interval ranging from 0 days to 11 weeks. In addition, the extent of abscesses, which ranged from no abscesses to multiple abscesses, seems to affect clinical outcome. As soon as an index case of wound botulism in IDUs is diagnosed, a coordinated public health case-management effort, including hospitals, outpatient clinics, and information centers for drug addicts, is mandatory to alert the medical community and the drug users to consider wound botulism if typical symptoms occur and to enable the prompt administration of antitoxin. Obtaining tissue samples or abscess fluid for culture and molecular epidemiologic studies of C. botulinum isolates is necessary to facilitate identification of the source of the contaminated heroin.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues from Department of Neurology, University of Cologne Medical Center, and the Department of Neurology, Municipal Hospital of Cologne, for providing clinical information, and Danuta Stefanic for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Kalka-Moll WM, Aurbach U, Schaumann R, Schwarz R, Seifert H. Wound botulism in injection drug users [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2007 Jun [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/eid/content/13/6/942.htm

References

- 1.Bleck TP. Clostridium botulinum (botulism). In: Mandell GL, Bennett, JE, Dolin, RD, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. p. 2822–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald KL, Rutherford GW, Friedman SM, Dietz JR, Kaye BR, McKinley GF, et al. Botulism and botulism-like illness in chronic drug abusers. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:616–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Passaro DJ, Werner SB, McGee J, Mac Kenzie WR, Vugia DJ. Wound botulism associated with black tar heroin among injecting drug users. JAMA. 1998;279:859–63. 10.1001/jama.279.11.859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brett MM, Hallas G, Mpamugo O. Wound botulism in the UK and Ireland. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:555–61. 10.1099/jmm.0.05379-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Update zu einer Häufung von Wundbotulismus bei injizierenden Drogenkonsumenten in Nordrhein-Westfalen Epidemiologisches Bulletin. Berlin: Robert Koch Institut; 2005.

- 6.Lindstrom M, Keto R, Markkula A, Nevas M, Hielm S, Korkeala H, et al. Multiplex PCR assay for detection and identification of Clostridium botulinum types A, B, E, and F in food and fecal material. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5694–9. 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5694-5699.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeshi K, Fujinaga Y, Inoue K, Nakajima H, Oguma K, Ueno T, et al. Simple method for detection of Clostridium botulinum type A to F neurotoxin genes by polymerase chain reaction. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nevas M, Lindstrom M, Hielm S, Bjorkroth KJ, Peck MW, Korkeala H. Diversity of proteolytic Clostridium botulinum strains, determined by a pulsed-field gel electrophoresis approach. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:1311–7. 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1311-1317.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon RJ, Lowy FD. Bacterial infections in drug users. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1945–54. 10.1056/NEJMra042823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandrock CE, Murin S. Clinical predictors of respiratory failure and long-term outcome in black tar heroin-associated wound botulism. Chest. 2001;120:562–6. 10.1378/chest.120.2.562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]