Abstract

This study examines transitions in schooling, sexual activity, and pregnancy for adolescents and young adults in urban South Africa. The study analyzes data from the Cape Area Panel Study (CAPS), a recently collected longitudinal survey of young adults and their families in metropolitan Cape Town. South African youth have high school enrollment rates through their teenage years, combined with relatively early sexual initiation, with most young people becoming sexually active while they are enrolled in school. Teen pregnancy rates are also relatively high, with almost all teen pregnancies being non-marital. We find that teen pregnancy is not entirely inconsistent with continued schooling, especially for African (black) women. Over 50% of African women who had a pregnancy at age 16 or 17 were enrolled in school the following year. We estimate probit regressions to identify the impact of individual and household characteristics on sexual debut, pregnancy, and school dropout between 2002 and 2005. We find that male and female students who performed better on a literacy and numeracy exam administered in 2002 were less likely to become sexually active and less likely to drop out of school by 2005. Surprisingly, 14-16 year-olds who had completed more grades in school in 2002, conditional on their age, were more likely to sexually debut by 2005, a potential indicator of peer effects resulting from the wide dispersion in age-for-grade in South African schools.

Introduction

As social transformation continues in South Africa and the opportunities available to young adults increase, it is important to understand how educational opportunities are related to subsequent transitions to adulthood. The goal of this paper is to examine the interactions between educational transitions and transitions into sexual activity and pregnancy among urban youth, including analysis of how early educational achievement affects sexual debut, pregnancy, and school dropout as adolescents progress through secondary school.

Past research has established a strong association between schooling and the timing of sexual initiation and pregnancy in developing countries (Bledsoe et al. 1999). However, the vast majority of studies use cross-sectional data to find that educational attainment and school enrollment are negatively associated with the probability of initiating sex and having an early pregnancy. At the same time, research on educational outcomes has shown a weak connection between grade attainment and basic knowledge (Lloyd, 2005). School enrollment and grade attainment alone do not give a complete picture about the knowledge and skills of young people. This is especially true in South Africa, where young people have achieved high levels of school enrollment and grade attainment but where persistent educational inequalities are reflected in high rates of grade repetition and widely varying educational achievement.

The importance of examining the interaction of educational achievement with sexual debut and pregnancy is that the timing and order of these transitions may have important effects on subsequent transitions in schooling, employment, and family formation. Understanding how adolescents negotiate these transitions has important policy implications and is crucial for successful well-being. Data limitations in developing countries, particularly the lack of information on sequencing of events and the lack of data on knowledge acquisition has limited our ability to understand the interconnections of educational outcomes with sexual and reproductive outcomes. We take advantage of waves 1-4 of the Cape Area Panel Study (CAPS), a recently collected longitudinal survey of young people in metropolitan Cape Town, to examine the transitions to sexual debut, pregnancy, and school dropout for both male and female young adults in urban South Africa. Our focus is on the interactions between schooling and sexual behavior, including analysis of whether adolescents with more acquired human capital have later sexual initiation and are less likely to have teen pregnancies.

The paper contributes to the debate and policy implications on transitions to adulthood in three key ways. First, the paper considers the sequencing of events. Our data allow us to measure educational achievement prior to sexual debut, pregnancy and school drop-out. Educational achievement, which we measure using a literacy and numeracy test administered to all CAPS respondents, reflects the knowledge base and skills set of young people. This provides a more direct measure of learning skills than grade attainment alone, and provides information about the educational differences taking place in a country where school enrollment and educational attainment are high for all groups. Second, we look at how the trajectories of adolescents differ across population groups. This is a particularly important dimension in the South African context, given the large racial differences in school quality and household circumstances. Third, we explore the interconnections between sexual and reproductive transitions and education for both males and females. In contrast to the extensive literature on transitions to adulthood of females, the literature on males is quite sparse and there are reasons to believe that these processes may vary substantially by gender.

The structure of this paper is as follows: We begin with a brief review of literature on transitions in schooling and sexual activity in developing countries, including research from South Africa. After describing the key features of the Cape Area Panel Study, we use the data to analyze transitions out of school and into sexual activity and pregnancy. We show that most sexual activity begins while students are still enrolled in school, and that pregnancy is not entirely incompatible with continued schooling. We then use the CAPS data to follow young women before and after their first pregnancy, looking at their trajectories in school enrollment and grade attainment. We show that girls who later experience a teen pregnancy tended to have lower enrollment rates and lower grade attainment several years before the pregnancy occurred. We then estimate probit regressions for sexual debut, pregnancy, and dropping out of school between 2002 and 2005 for the sample of CAPS respondents aged 14-16 in 2002. These regressions take advantage of the fact that we have measures of individual and household characteristics before the transitions occur, and allow us to look at the impact on sexual initiation and pregnancy of variables such as prior educational achievement and household income.

Our regression results indicate that higher scores on a literacy and numeracy exam administered in 2002 are associated with lower probabilities of sexual debut and school dropout for both males and females. Surprisingly, however, those with higher grade attainment in 2002, conditional on their age and other characteristics, are more likely to experience sexual debut by 2005. We conjecture that this result may be due to peer effects related to the high rates of grade repetition in South Africa, with students who are farther ahead in school interacting with older classmates. We also find that adolescent girls living in households that experience an economic shock are more likely to experience sexual debut, pregnancy, and school dropout.

Interconnections between Sexual Debut, Teen Pregnancy, and Schooling

There is a long tradition of research examining the relationships between education, adolescent sexual initiation, and childbearing in developing countries (Bledsoe et al. 1999; Lloyd 2005). Research has typically found adolescent school enrollment and schooling to be negatively associated with the probability of sexual initiation and early childbearing (Gupta and Leite 1999; Lloyd and Mensch 2008). Evidence reported in the National Academy of Sciences report on transitions to adulthood in developing countries shows that adolescent girls attending school are half as likely as their unmarried peers who are out of school to have ever had sex (Lloyd 2005). One explanation of this association is that success in negotiating sexual initiation and parenthood is more likely to be ensured if other transitions occur prior to sexual debut and parenthood.

Examining the timing of sexual initiation is important because the age of sexual debut affects the risks of pregnancy and childbearing, as well as the risks of transmitting and contracting sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including HIV/AIDS. Evidence on the timing of first sexual initiation points to several important implications for childbearing and other transitions to adulthood. First, early entry into sexual life and the context within which sexual intercourse begins are key indicators of adolescents' potential risk for unplanned pregnancy, abortion and sexually transmitted diseases (Singh et al 2000). There has also been empirical evidence in Sub-Saharan Africa showing that girls appear vulnerable to dropping out of school once they become sexually mature and engage in premarital sex (Biddlecom et al. 2006).

Studying the interactions between schooling and sexual initiation and pregnancy is especially interesting in South Africa, since it is not uncommon for girls to continue school after the birth of a child. This differs from many other African countries. Kaufman et al. (2001) found that many South African girls return to complete their schooling after giving birth and that this is a function of support from the girl's family and paternal recognition of the child. In a recent study in rural South Africa, Madhavan and Thomas (2005) confirm that childbearing impedes school enrollment and schooling, but young mothers can succeed in their educational careers if provided with flexible child care options.

One problem with most past studies is that the data generally do not provide information on the sequencing of events. It is therefore not clear whether adolescents left school and got pregnant or vice-versa. In many studies pregnancy and sexual debut are assumed to be exogenous, with researchers looking at the impact of teen pregnancy on school attainment. However, pregnancy could be the result of school dropout and poor school performance, or third variables could drive both sets of outcomes. Without information on the sequencing of events it is not possible to identify whether young adults were doing poorly in school and then got pregnant or whether they got pregnant and ended up not finishing high school, for example. In fact, a plausible explanation found for the United States is that girls who eventually dropped out of school and did not advance grades were already doing poorly in school prior to their pregnancy (Geronimus and Korenman 1993).

More recently there have been a few studies linking education to sexual and reproductive behaviors in developing countries considering both the timing of events and additional variables characterizing the educational process. These studies focus on how experiences with school are related to adolescent reproductive outcomes. Lloyd and Mensch (2008) found that adolescents with slower school progress in four West African countries had higher probability of a teen birth. Using information from the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal, Grant and Hallman (2006) found that prior school progress measured by temporary school withdrawal and grade repetition are significant predictors of both the likelihood of pregnancy and of dropping out of school after a pregnancy. Similarly, Marteleto et al. (2006) found that having repeated a high proportion of grades prior to the start of the reproductive years is associated with teen childbearing as well as with a smaller probability of returning to school after a birth. They also find that early life family social capital and social environment are important factors leading to early childbearing and also preventing girls from returning to school after a teen birth. The results suggest that an unsuccessful educational career is not the result of an isolated event but rather of a series of cumulative disadvantages throughout a young person's life.

Taken together, these results indicate that early life characteristics and prior school experience are important factors associated with the sexual and reproductive behavior of adolescents. Most past studies examining transitions to adulthood were typically limited to understanding education as school enrollment, years of schooling completed, or grade repetition, with no attempt to measure ability, proficiency and skills. In a context where almost all young adults are in school and where grade repetition is commonplace, what is not clear is how measures of educational performance that capture the wide variation of learning skills and quality of schools are associated with sexual and reproductive behaviors.

Sexual Debut, Childbearing and Schooling in South Africa

There are important features to sexual debut, adolescent childbearing and schooling that make South Africa an important setting to examine these outcomes in relation to educational achievement. In most developing countries, first sexual intercourse occurs predominantly outside marriage among males but largely within marriage among females (Singh et al. 2000). South Africa differs from this pattern, with sexual initiation occurring primarily outside marriage. According to the 1998 South Africa Demographic and Health Survey, the median age at first sex was 17.8 for women aged 20-24 and 18.4 for women aged 25-49. The median age of marriage of women aged 25-49 was 24.2, suggesting that sexual debut often takes place before marriage (Macro International 2008).

South Africa is characterized by low fertility levels relative to other African countries, although adolescent fertility rates are relatively high. The Total Fertility Rate of 2.8 based on the 2001 Census (Moultrie and Dorrington 2004) is one of the lowest in Africa. Although South Africa's TFR ranks the 4th lowest in the continent, adolescent fertility ranks only the 15th lowest (United Nations Population Division 2003). Given declines in fertility at older ages, the proportion of adolescent fertility relative to total fertility has been increasing in South Africa (Moultrie and Dorrington 2004). As shown in Lloyd's (2007) summary of data from Demographic and Health Surveys, South Africa has one of the highest proportions of 15 year-old girls enrolled in school and also one of the highest proportions of 15-17 year-old girls who have had sex, in comparison to other countries in Africa and Latin America. Young ages of sexual initiation, relatively high levels of adolescent fertility, and late ages of marriage yield high rates of unmarried childbearing. Most teenage births in South Africa are non-marital, a pattern we document below with data from the Cape Area Panel Study.

Another critical issue facing young people in South Africa is HIV/AIDS, which, given its pervasiveness, is likely to be having an important impact on sexual activity. We do not look directly at the role of HIV/AIDS in this paper, in part because CAPS does not do HIV testing and does not ask directly about HIV status. CAPS does include questions about HIV knowledge and perceived HIV risk. Using the CAPS data, Anderson and Beutel (2007) have shown that there is relatively high degree of HIV knowledge among Cape Town youth. Anderson, Beutel, and Maughan-Brown (2007) found that female CAPS respondents who reported higher perceived risk of contracting HIV in 2002 were less likely to sexually debut between 2002 and 2005. This suggests that the perceived risk of contracting HIV may be affecting sexual activity.

South Africa has achieved high levels of school enrollment and grade attainment, although there continue to be large racial differences in schooling in terms of both quality and quantity. As we will see below, there are still large racial differences in grade attainment. On average, coloureds and Africans do not finish high school nor advance to college degrees, while whites progress to university. There are also strong differences in rates of grade progression and educational achievement (Lam, Ardington, and Leibbrandt 2007). In this regard, South African youth mirror the old racial hierarchy of the apartheid era. White students get more schooling and get it faster, get work experience at younger ages, and find employment with higher probability than African youth, with coloured young adults falling in between. Racial differences in grade attainment tell only part of the story. Although there are greater opportunities for school choice in post-apartheid South Africa, constraints facing students are such that most African students are still in low quality schools. As we will see, there are enormous racial differences in performance on the literacy and numeracy test administered in CAPS, differences that may have an important effect on subsequent sexual and reproductive transitions.

There are many reasons why the quantity and quality of schooling experienced by young people will have important effects on young adults' transitions to adulthood (Lloyd 2005). There has been relatively little research, however, focusing on how prior educational achievement is related to sexual initiation and teen pregnancy in developing countries. This may be partly due to the fact that the literature on school quality and academic achievement in developing countries has developed largely independently of literature on the interconnections of educational outcomes with reproductive and sexual behavior (Buchmann and Hannum 2001). In addition, few data sets have direct measures of educational achievement combined with detailed information on family background and sexual and reproductive behavior.

Data

We use data from Waves 1-4 of the Cape Area Panel Study (CAPS), a longitudinal survey of young people s in metropolitan Cape Town. Details about CAPS are provided in Lam, Seekings, and Sparks (2006).1 Wave 1 was conducted in 2002, and included a household questionnaire with data on the entire household as well as a detailed young adult questionnaire administered to up to three young adults aged 14-22 living in the household. The young adult questionnaire collected data on a wide range of topics such as schooling, employment, sexual activity, and childbearing. The young adult questionnaire also included a life history calendar that provides retrospective information on living arrangements, schooling, and pregnancy. Wave 1 also included a literacy and numeracy evaluation, which will be discussed below.

CAPS was designed using a two-stage probability sample of households, with an oversampling of African and white households in order to get large enough samples to make meaningful comparisons across groups. The baseline wave of CAPS surveyed 4,751 young adults in 3,304 households. As in most South African household surveys, response rates were high in African and coloured areas and low in white areas. Household response rates were 89% in African areas, 83% in coloured areas, and 46% in white areas.2 Young adult response rates, conditional on participation of the household, were high, even in white areas. Given household participation, response rates for young adults were 93% in African areas, 88% in coloured areas, and 86% in white areas (Lam, Seekings, and Sparks, 2006).

Wave 2 of CAPS took place in 2003 and 2004. Wave 3 took place in 2005, and provides most of the longitudinal information used in this paper. We also use data from Wave 4, which took place in 2006, in order to fill in information for respondents who were interviewed in Wave 4 but were not interviewed in Wave 3. Table 1 summarizes the sample size by population group, and provides information on sample attrition between waves. We present information for the full sample aged 14-22 in 2002, which is used for some of the analysis in the paper, and for the subset that was aged 14-16 in 2002, the sample we use for our probit regressions analyzing transitions between 2002 and 2005. As seen in Table 1, the original Wave 1 sample included roughly equal numbers of African and coloured respondents, as was planned in the sample design. The weighted percent column shows that when sample weights are used to adjust for the sample design and differential response rates, the weighted sample is 28% African, 53% coloured, and 19% white, proportions that are similar to those found for the same age group in Cape Town in the 2001 South African census (Lam, Seekings, and Sparks, 2006).

Table 1. Sample size by population group and attrition between waves, Cape Area Panel Study Waves 1-4.

| Population group | Wave 1 | Unweighted percent | Weighted percent | Interviewed in Wave 3 | Interviewed in Wave 3 or Wave 4 | Attrition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample aged 14-22 in 2002 | ||||||

| Black/African | 2,151 | 45.3 | 28.2 | 1,515 | 1,724 | 19.9% |

| Coloured | 2,005 | 42.2 | 53.2 | 1,679 | 1,801 | 10.2% |

| White | 595 | 12.5 | 18.6 | 337 | 391 | 34.3% |

| Total | 4,751 | 100 | 100 | 3,531 | 3,916 | 17.6% |

| Sample aged 14-16 in 2002 | ||||||

| Black/African | 664 | 41.7 | 26.3 | 515 | 570 | 14.2% |

| Coloured | 715 | 44.9 | 54.8 | 633 | 672 | 6.0% |

| White | 212 | 13.3 | 19.0 | 157 | 171 | 19.3% |

| Total | 1,591 | 100 | 100 | 1,305 | 1,413 | 11.2% |

As seen in Table 1, 3,531 of the 4,751 original respondents were successfully interviewed in Wave 3 in 2005. In 2006 we attempted to follow all of the original respondents and located almost 400 additional respondents that were missed in 2005. Because we collect retrospective data on variables such as schooling, sexual activity, and pregnancy to cover the period since the respondent was last interviewed, we can use the Wave 4 interview to fill in information on 2005 outcomes for respondents who were in Wave 4 but not in Wave 3. The effective sample for 2005 outcomes, then, is 3,916, implying a 17.6% overall attrition rate between 2002 and 2005.

As Table 1 demonstrates, attrition rates differ significantly by race. The African attrition rate is 20%, with proxy reports indicating that most attrition is due to migration back to the rural Eastern Cape province, the main sending region for Africans living in Cape Town. The coloured population has its roots primarily in Cape Town, a factor contributing to its lower 10% attrition rate. The 34% attrition rate for whites includes both migration out of Cape Town (including out of South Africa) and a significant number of refusals. The bottom panel of Table 1 shows the sample size and attrition rates for the sample that was aged 14-16 in 2002, the group we use in our regressions. Attrition for this group is considerably lower than for the full sample, 11% overall, a reflection of the generally positive relationship between age and attrition CAPS has experienced in every wave.

Table 2 provides more detail about attrition for the sample that was aged 14-16 in 2002. Using key baseline characteristics, we compare the 2002 sample with the sample that was successfully followed to 2005 (recalling that 2005 data was sometimes reported retrospectively in 2006). Table 2 also limits the sample to those for whom we have data on sexual activity, the sample we use for our regressions (this reduces the sample by only a few observations). The striking feature of Table 2 is that the differences between the original sample and the sample that was followed are very small. For example, attrition is almost entirely unrelated to baseline sexual activity. The proportion of African females aged 14-16 that reported having had sex in 2002 was 24%. When we look only at the 86% of these respondents that were successfully followed to 2005, the proportion that had sex by 2002 was 23%. Looking at characteristics such as school enrollment, grade completion, and household income, the mean for the sample that was followed is typically within 2-3% of the mean for the original sample. One exception is a large percentage difference in the literacy/numeracy scores of the original sample versus the followed sample for coloureds. This is an artifact of the fact that their mean is very close to zero on the standardized score. The absolute difference is only 0.01 standard deviations, essentially no difference. Those who were followed were somewhat more likely to be living with parents in 2002. In particular, whites living with their fathers in 2002 were more likely to be successfully followed.

Table 2. Comparison of 2002 characteristics of original sample with sample followed in 2005, CAPS respondents aged 14-16 in 2002.

| African | Coloured | White | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 2002 | 2005 | Ratio | 2002 | 2005 | Ratio | 2002 | 2005 | Ratio |

| Female | |||||||||

| Number of observations | 371 | 319 | 0.860 | 379 | 353 | 0.931 | 96 | 77 | 0.802 |

| Enrolled in school | 0.94 | 0.95 | 1.016 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 1.002 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 |

| Number grades completed | 7.43 | 7.42 | 0.999 | 8.07 | 8.09 | 1.002 | 8.13 | 8.10 | 0.996 |

| Literacy/numeracy score | -0.52 | -0.54 | 1.033 | -0.05 | -0.04 | 0.783 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 0.997 |

| Ever had sex | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.966 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.942 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1.238 |

| Mother's schooling | 8.26 | 8.26 | 1.000 | 8.47 | 8.48 | 1.002 | 12.36 | 12.42 | 1.005 |

| Father's schooling | 7.35 | 7.33 | 0.997 | 8.87 | 8.86 | 0.999 | 13.04 | 13.11 | 1.006 |

| Living with mother | 0.66 | 0.69 | 1.045 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 1.007 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.984 |

| Living with father | 0.38 | 0.40 | 1.047 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 1.040 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 1.107 |

| Household income | 353 | 354 | 1.003 | 865 | 870 | 1.005 | 3917 | 4008 | 1.023 |

| Male | |||||||||

| Number of observations | 292 | 250 | 0.856 | 335 | 310 | 0.925 | 112 | 84 | 0.750 |

| Enrolled in school | 0.94 | 0.95 | 1.014 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 1.009 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.009 |

| Number grades completed | 6.83 | 6.89 | 1.010 | 7.63 | 7.64 | 1.001 | 8.02 | 8.12 | 1.013 |

| Literacy/numeracy score | -0.68 | -0.63 | 0.928 | -0.03 | -0.02 | 0.923 | 1.17 | 1.23 | 1.051 |

| Ever had sex | 0.27 | 0.28 | 1.018 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 1.044 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.444 |

| Mother's schooling | 8.60 | 8.61 | 1.002 | 8.71 | 8.73 | 1.002 | 12.61 | 12.61 | 0.999 |

| Father's schooling | 7.38 | 7.38 | 1.000 | 8.88 | 8.86 | 0.998 | 12.94 | 12.95 | 1.001 |

| Living with mother | 0.75 | 0.77 | 1.025 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.996 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1.008 |

| Living with father | 0.42 | 0.43 | 1.026 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 1.016 | 0.73 | 0.77 | 1.063 |

| Household income | 372 | 372 | 1.000 | 888 | 892 | 1.004 | 3972 | 3950 | 0.995 |

Note: Limited to respondents with information about sexual activity. All characteristics measured in CAPS Wave 1 in 2002. Household income per capita in rands per month.

Overall, Table 2 gives little evidence that attrition is significantly related to baseline sexual behavior, schooling, or household characteristics. Given CAPS target sample of highly mobile adolescents transitioning into adulthood, the attrition rates seem reasonable, especially in light of the evidence in Table 2. We think attrition should not create serious problems for our analysis, though it is important to keep it in mind in interpreting our results. Selection into the Wave 3 and Wave 4 samples with regard to sexual activity and pregnancy between waves could be either positive or negative. On the one hand, young women who get pregnant may be more likely to stay in Cape Town and stay in contact with their Wave 1 household, making them easier to track. On the other hand, pregnancy may lead some young women, especially Africans, to return to the rural area where they have access to the help of parents or grandparents for child care. For our multivariate regressions we think it is reasonable to assume that attrition is unlikely to affect our estimates of the impact of variables such as schooling or household income on outcomes such as sexual debut, once we control for characteristics such as age and race.

One important theme throughout the paper is the comparison of schooling and sexual behavior for African, coloured, and white youth. These three population groups were subject to very different treatment under apartheid, and many remnants of that legacy persist. Whites had advantages in a wide range of areas, including significantly higher expenditures on schooling, privileged access to the labor market, unrestricted residential mobility, and better access to social services. Africans had the least access to services and the most restrictions on work and migration, with a large gap in expenditures on schooling. The coloured population, which is heavily concentrated in Cape Town, occupied an intermediate status under apartheid, with higher expenditures on schooling and other services, fewer restrictions on residential mobility, and better access to jobs than Africans. While roughly 50% of Cape Town is coloured, as seen in Table 1, only about 10% of the South African population was coloured in the 2001 census.3 As we will see below, large disparities persist in income and schooling across these groups, and Cape Town continues to be highly residentially segregated.

An important caveat throughout the paper is that the white sample is small, had the poorest response rate in Wave 1, and had the highest attrition between waves. Attrition is highest for older males who had the most schooling in Wave 1, an indication of the high mobility of this group. Attrition may be correlated with unobserved determinants of schooling and sexual behavior, although it seems unlikely that the enormous racial differences observed in almost every dimension are the result of differential response rates or attrition bias. While we worry about how well our white sample represents the full population of white youth in South Africa, we include whites in our analysis because they provide an interesting point of comparison.

One interesting feature of CAPS is the literacy and numeracy evaluation (LNE) that was administered to all youth respondents in Wave 1. This was a self-administered written test taken after completion of the young adult questionnaire. The test was designed specifically for CAPS by South African educators, with the goal of testing a broad range of ages and abilities in a short time period. The test had 45 questions and took about 20 minutes to complete. Respondents could choose to take the test in English or Afrikaans. There was no version in Xhosa, the home language of most African respondents. The English language test was taken by 99% of African respondents, 43% of coloured respondents, and 64% of white respondents. In interpreting the results it is important to keep in mind that most white and coloured students took the test in their first language, while Africans took it in a second language. It should also be noted, however, that English is the official language of instruction in African schools and is used for tests such as the grade 12 matriculation exam. We use the LNE scores as a measure of cumulative learning at the time of the 2002 interview. Test scores reflect many factors, including innate ability, home environment, and the quantity and quality of schooling to that point.

Transitions out of school and into sexual activity

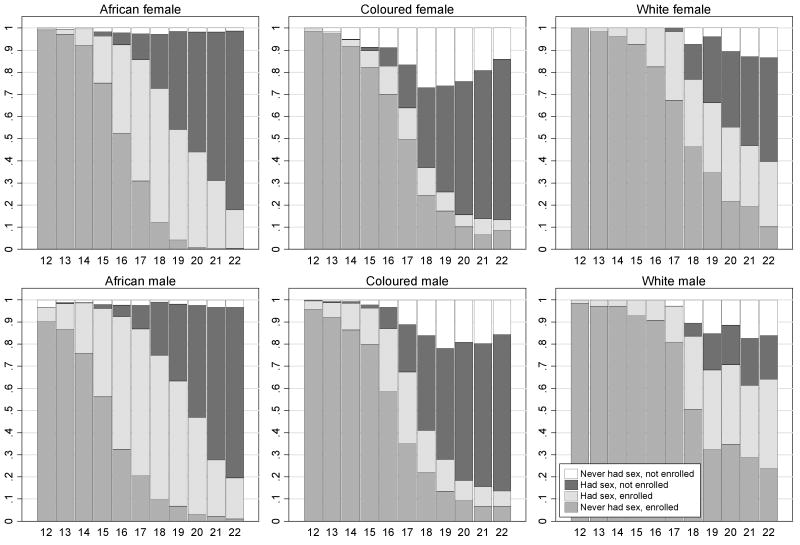

We begin our analysis of CAPS data by looking at transitions out of school and into sexual activity. Figure 1 shows the joint enrollment/sexual initiation status of females and males from age 12 to 22, as reported by respondents aged 22 to 25 in 2005. The reports combine the retrospective reports in Wave 1 in 2002 with the longitudinal reports from Waves 2, 3, and 4. An advantage of these transitions is that they represent the actual experience of a cohort of young people, rather than the mix of age and cohort effects that are captured in a typical cross-sectional age profile. The figure shows each of the four possible combinations of school enrollment and sexual initiation, where schooling includes post-secondary education. A striking feature of African profiles is that the category “Never had sex, not enrolled” is almost empty for both males and females. Since young people who first have sex after leaving school must spend some time in this state, the very small proportion in this category suggests that sexual debut almost always occurs while youth are enrolled in school. This results from the combination of relatively early sexual debut and continued high rates of school enrollment into the late teens. Combining the “Never had sex, enrolled” and “Had sex, enrolled” bars, African enrollment rates at age 17 are over 85% for both males and females. Among those 17 year-old Africans enrolled in school, 64% of females and 76% of males report having ever had sex.

Figure 1.

Transitions out of school and into sexual activity CAPS respondents aged 22-25, 2005

Figure 1 shows large and interesting racial differences in schooling and sexual activity. While a significant fraction of African women are in school after they become sexually active, coloured women tend to spend relatively little time in school after sexual debut. Looking at females aged 17, for example, 55% of Africans are in the category “had sex, enrolled,” by far the largest of the four categories, while only 14% of coloureds are in that category. The percentage of African women in the “had sex, enrolled” category is 40-60% from age 16 to 20, while the percentage of coloured women in this category is never above 14%. Similar differences are observed for men, with both African men and coloured men more likely to be in the “had sex, enrolled” category than their female counterparts at most ages.

Both male and female enrollment rates are lower for coloured youth than for African youth, although this is potentially misleading in terms of schooling attainment. As shown in Lam et al. (2007), coloured youth are ahead of African youth in grade attainment by age 17. Coloured youth begin to drop out of school at a higher rate than African youth around age 17, but there continues to be a small coloured advantage in grade attainment at age 22. A similar phenomenon applies to gender differences for all three racial groups. While women have lower enrollment rates than men in each group starting around age 18, women have higher grade attainment at that point, primarily because they have lower rates of grade repetition. The female schooling advantage narrows somewhat above age 18, but women continue to have higher grade attainment than men in all three racial groups at age 22.

Figure 1 shows that transitions into sexual activity differ by gender. Boys tend to become sexually active at a somewhat earlier age than girls among Africans and coloureds, although this is not true for whites. For example, 46% of African females have had sex by age 16, compared to 65% of African males. These gender differences are relatively small compared to the very large racial differences, however, with only 21% of coloured females and 38% of coloured males report having had sex by age 16. Rates are even lower among whites, with only 17% of white females and 9% of white males report having ever had sex by age 16.

We have no way to know the accuracy reported sexual activity, or how accuracy differs by race and gender. Although interviewers were trained to interview respondents privately, this was not always easy in the small crowded households in which many young people live. While the lack of privacy was most serious in African households, African teenagers are the most likely to report having had sex. Cultural acceptability of pre-marital sexual activity undoubtedly differs across groups, with many coloured and white families living in socially conservative areas. It is possible that the low rates of sexual activity among white respondents result from a greater reluctance to admit to premarital sexual activity. It is interesting, however, that white females are more likely to report having had sex than are white males at every age, a result that seems unlikely to be driven by social desirability bias in responses. For example, 68% of white females report having had sex at age 20, compared to 54% of white males. We suspect that this results from the fact that women are having sex with men who are at least one or two years older.4

Transitions from School to Pregnancy

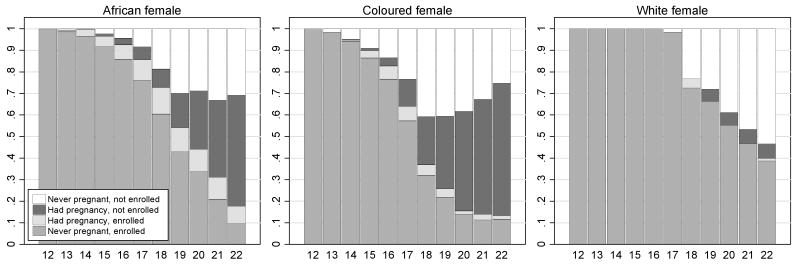

Figure 2 shows the transitions out of school and into pregnancy for females, looking at the same sample used for Figure 1. We use pregnancy reports because, as we show below, over 95% of reported pregnancies in CAPS become live births, and because we want to include incomplete pregnancies. We leave males out of this analysis since we think their reports of having made someone pregnant are likely to be reported with a great deal of error (although we include them in the regressions below). There are several interesting patterns in Figure 2. First, just as African women are more likely than coloured women to combine sexual activity and school enrollment, African women are also more likely to combine pregnancy and school enrollment. The percentage of African women in the “had pregnancy, enrolled” category is 12% at age 18, compared to 5% for coloured women.

Figure 2.

Transitions out of school and into pregnancy CAPS respondents aged 22-25, 2005

Adding together the two middle bars in each graph, pregnancy rates for coloured women in the teenage years are actually higher than the pregnancy rates for African women, in spite of the fact that significantly higher fractions of African women report having had sex at every age. For example, the percentage of 17-year-olds who have been pregnant is 19% for coloureds and 16% for Africans, while the percentage who ever had sex is 34% for coloureds and 66% for Africans.

Another important pattern in Figure 2 is that pregnancy and school enrollment are by no means mutually exclusive, especially for African women. African women who have been pregnant are more likely to be enrolled than not enrolled at every age up until age 19. Looking at the 16% of 17 year-old African women who report having had a pregnancy, 62% are enrolled in school. The pattern for coloured women is quite different, with much smaller proportions of women reporting that they have both had a pregnancy and are still in school. Of the 19% of 17 year-old coloured women who report having had a pregnancy, only 35% are enrolled in school. Only a tiny proportion of the white women in our sample report having been pregnant, making it difficult to draw many inferences about the relationship between school and pregnancy.

The fact that teenage African women have somewhat lower pregnancy rates than coloured women even though African women become sexually active at an earlier age is an intriguing result. Given the fact the coloured households are generally more prosperous than African households and tend to have better access to most social services, it seems unlikely that coloured women have less access to contraception. In future research we plan to link the CAPS data to information on the location of health and family planning clinics. It is possible that reporting bias plays a role, with coloured women less likely to report pre-marital sexual activity unless it results in a pregnancy. Whatever the explanation of this large reported difference in the timing of sexual activity and pregnancy between these two population groups, it does seem clear that African teenagers have a relatively high capacity for avoiding pregnancy after becoming sexually active. This is one reason why it is possible to have such high proportions of women enrolled in school after they have become sexually active. Another reason is that it is possible to stay in school even after becoming pregnant, an issue we investigate in more detail below.

An important issue in understanding the competition between pregnancy and schooling is whether pregnancy leads to a birth. CAPS collects considerable detail about each pregnancy, including the pregnancy outcome. Table 3 summarizes the outcomes of the first pregnancy reported by all women with data for 2005.5 About 40% of African and coloured women in CAPS had a pregnancy by 2005, at which time the respondents were age 16 to 26. If we assume that women who were still pregnant in the 2005 interview had a live birth, then about 95% of all pregnancies become live births for young African and coloured women. White women report a miscarriage rate of 13%, but this corresponds to only one miscarriage out of six pregnancies. Reports of abortion are very rare in our data – only five abortions are reported out of 824 pregnancies. While this is likely to understate the true number of abortions, we have no way to estimate the degree of under-reporting.6 About 5% of pregnancies are reported as stillbirths or miscarriages. While it is impossible to know the extent of under-reporting of abortions, miscarriages, and stillbirths, one thing that is clear is that when women report a pregnancy it results in a birth about 95% of the time. Given this, and given the fact that some pregnancies are still underway in every CAPS wave, we focus our analysis in the rest of the paper on pregnancies, with an understanding that almost all of these pregnancies result in births.

Table 3. Percent ever pregnant and outcome of first pregnancy, female CAPS respondents aged 16-26 in 2005.

| African | Coloured | White | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women | 969 | 959 | 198 | 2126 |

| Percent ever pregnant | 43.4% | 40.5% | 3.2% | 35.8% |

| First pregnancy outcome | ||||

| Live birth | 92.6% | 87.7% | 86.9% | 89.4% |

| Still pregnant | 2.3% | 7.2% | 0.0% | 5.4% |

| Stillbirth | 2.1% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 1.5% |

| Miscarriage | 2.2% | 3.2% | 13.1% | 3.0% |

| Abortion | 0.6% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 0.5% |

| Refuse to say | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| Percent married at first pregnancy | 13.2% | 11.2% | 46.7% | 12.4% |

School Enrollment, Grade Attainment, and Timing of First Pregnancy

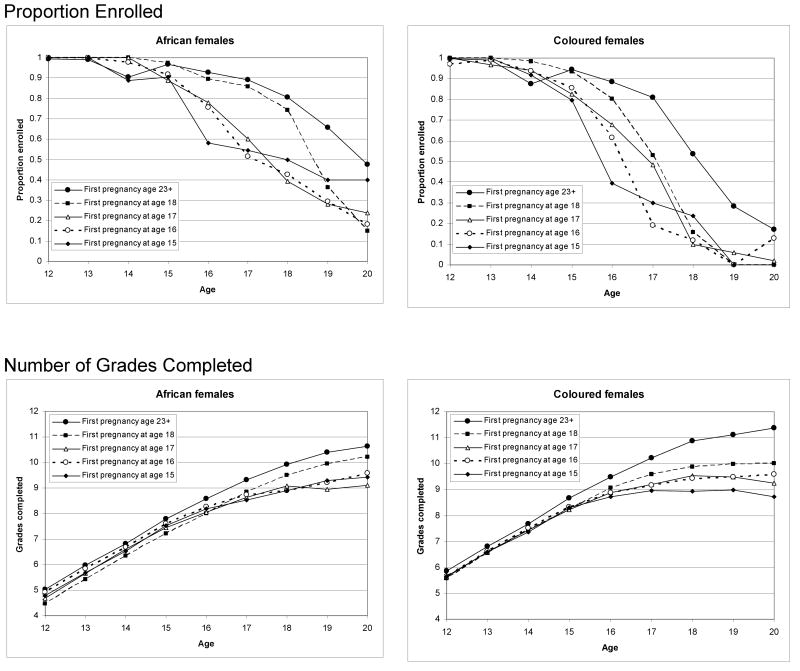

CAPS provides unusually rich data for analyzing the competition between pregnancy and schooling. Because we have a full schooling and pregnancy history, we can observe schooling trajectories before and after girls become pregnant. Figure 3 shows school enrollment rates and mean number of grades completed for African and coloured girls from age 12 to 20 by the age of their first pregnancy. Since our focus is on teen pregnancy, we consider the educational history of girls who had a first pregnancy at ages 15 to 18 and compare them to those who had their first pregnancy after age 23 (including those who had never been pregnant at the time of their last interview). Recall from Table 2 that 95% of these pregnancies resulted in live births, so the teen pregnancies shown here almost always imply a teen birth.

Figure 3.

Proportion enrolled and number of grades completed by age and timing of first pregnancy, African and Coloured females

The top panel of Figure 3 shows enrollment rates from age 12 to 22 by the age of first pregnancy. Enrollment rates are above 95% for both African and coloured girls up to age 13. Girls who will eventually experience a teen pregnancy begin to show declines in enrollment rates around age 14, including those who do not get pregnant until age 17. This suggests, not surprisingly, that there is a considerable degree of selectivity in the sample of girls who have teen pregnancies, and that teen pregnancy cannot be taken as exogenous when examining its impact on subsequent outcomes. For example, 11% of Africans and 35% of coloured girls who had a first pregnancy at age 17 were not enrolled in school at age 16. This an important point, as most research on pregnancy in developing countries makes the assumption those young women who report that they dropped out of school due to a pregnancy would have stayed in school otherwise. Other factors such as lack of social and economic opportunities for young women may result in school dropout and poor academic performance (Lloyd and Mensch 1999; Mensch et. al 2001). Below we will look at the impact of prior school performance on the probability of experiencing a pregnancy between 2002 and 2005.

While we must be cautious about attributing causality, it is clear that a large percentage of girls who were enrolled in school prior to a pregnancy do not continue in school after the pregnancy. At the same time, a significant percentage either does not drop out or returns to school after dropping out, especially among Africans. About 50% of African girls who get pregnant before completing high school were enrolled in school in the year after the pregnancy. Coloured girls, on the other hand, have mostly dropped out of school by the fear following the pregnancy, and rarely return to school after the birth of a child. This difference between Africans and coloureds may be related to the overall racial differences in dropout rates. African schools have higher rates of grade repetition, lower dropout rates, and a much larger variance in the distribution of grade for age. Lam et al. (2007) attribute this in part to a larger random component in grade advancement in African schools, making grade advancement to some extent a lottery. One implication of this is that African schools may be more “forgiving” in regard to young women returning to school after the birth of a child. Since, as we will show below, there is a wide age range in any grade, and since many students repeat grades, it is easier for young African mothers to re-insert themselves into the school environment than it would be in a school system with a sharper alignment of age and grade.

The bottom panel of Figure 3 shows grade attainment from age 12 to 20 by the age of first pregnancy. The trends in grade attainment for girls who had a teen pregnancy are similar to the trend for those who did not have a teen pregnancy up until age 14. However, girls who will eventually have a teen pregnancy already had slightly lower grade attainment even before age 14, when none of the girls had been pregnant. For example, at age 14 African girls who do not become pregnant before age 23 show approximately half a grade more schooling than those with a first pregnancy at age 16. These differences in grade attainment prior to the pregnancy are also observed for coloured girls.

Figure 3 shows that African girls who become pregnant often end up completing significant amounts of schooling after the pregnancy. For example, African girls who have a pregnancy at age 15 complete about two additional school grades between 15 and 20, ending up with a mean of 9.5 grades. The situation is very different for coloured girls. Coloured girls with a pregnancy at age 15 only gain about half a grade after age 15. While there is a strong relationship between age at first pregnancy and grade attainment at age 20 for both Africans and coloureds, the dispersion is much larger in the coloured sample. African girls seem to be more able to negotiate parenthood and schooling, continuing to accumulate schooling after giving birth.

As noted, one of the important features of the South African school environment is the high level of grade repetition, especially in predominantly African schools. This creates a wide dispersion in grade-for-age and is likely to reduce the stigma associated with returning to school after having a child. Table 4 shows the distribution of grades for 16-year-old males and females by population group. White females demonstrate what might be considered the target outcome, with 65% in grade 10 and 35% in grade 11. African males show the biggest discrepancy from that distribution. African males who were aged 16 in 2002 were distributed from Grade 5 to Grade 12, with grade 10 – the target grade for a 16-year-old who started school at age 7 – having only 22% of the total, and the modal grade – grade 9 – having only 34% of the total. African females, who tend to repeat fewer grades than African males, have a somewhat narrower distribution of grades, but still have only 26% in grade 10, 39% in grade 9, and 16% in grade 8. Coloured students also have significant grade repetition, though much less than that of Africans. Like whites, the modal grade for 16-year-old coloured youth is grade 10 (rather than the grade 9 observed for Africans), with about 46% of coloured males and females in Grade 10.

Table 4. Percentage in each grade in 2002, 16 year-olds enrolled in school in CAPS Wave 1.

| Female | Male | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade in 2002 | African | Coloured | White | African | Coloured | White |

| Grade 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Grade 6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Grade 7 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 1.8 | 0.0 |

| Grade 8 | 16.1 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 10.6 | 5.4 | 1.7 |

| Grade 9 | 39.3 | 20.4 | 0.0 | 33.7 | 29.5 | 9.3 |

| Grade 10 | 26.4 | 45.8 | 64.7 | 22.2 | 46.8 | 57.0 |

| Grade 11 | 10.9 | 31.0 | 35.3 | 8.6 | 13.1 | 30.5 |

| Grade 12 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 1.5 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

These patterns are important in understanding transitions in schooling, sex, and pregnancy. First, they help explain why African girls find it possible to be in school after having a child. The high levels of grade repetition and the loose connection between age and grade may make it easier to return to school after having a child. Second, the heterogeneity in age in a given grade may cause the sexual activity of older youth to have spillover effects on younger classmates. We return to this below when we discuss our result that higher grade attainment, controlling for age, appears to encourage rather than deter sexual activity and childbearing.

Probit Regression Results

In this section we present probit regression results for three outcomes – sexual debut, pregnancy, and dropping out of school – estimated separately for males and females. One of our key empirical questions is whether prior educational achievement has a strong impact on each of these transitions. Given the differences in proficiency and skills reflected in educational achievement, we hypothesize that students with higher test scores are more likely to delay sexual debut, avoid pregnancy and continue in school from 2002 to 2005. We are also interested in looking at racial and gender differences in these outcomes.

Table 5 presents means and standard deviations of our dependent and independent variables, along with other variables that are useful in interpreting our results. Our sample for the regressions is CAPS respondents who were aged 14-16 in 2002 and for whom we have data on the relevant outcomes for 2005. The information for 2005 outcomes comes from both Wave 3 (2005) and Wave 4 (2006). Most respondents were aged 17-19 in 2005, although the full age range is 16-20 in 2005.7 Looking at the first two rows of Table 5, we see that 22% of African females aged 14-16 reporting having had sex by 2002, with 77% of this same group having had sex by 2005. As shown in the third row, this implies that 68% of those who had not had sex in 2002 experienced sexual debut between 2002 and 2005. We once again see large racial differences in sexual activity, with sexual debut rates of only 31% for coloureds and 28% for whites over the same period. Our first outcome measure in our probit regressions will be sexual debut, equal to 1 if a respondent reported not having had sex in 2002 but reported having had sex by 2005. The mean of the sexual debut variable for males is fairly similar to that of females – 58% for Africans, 33% for coloureds, and 32% for whites.

Table 5. Means and standard deviations of key variables, Cape Area Panel Study respondents aged 14-16 in 2002 who were followed in 2005.

| Female | Male | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | African | Coloured | White | African | Coloured | White |

| Sexual activity and pregnancy | ||||||

| Had sex by 2002 | 0.22 (0.42) | 0.06 (0.23) | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.28 (0.45) | 0.09 (0.28) | 0.01 (0.09) |

| Had sex by 2005 | 0.77 (0.42) | 0.37 (0.48) | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.32 (0.47) |

| Sexual debut 2002-2005 | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.28 (0.45) | 0.58 (0.50) | 0.33 (0.47) | 0.32 (0.47) |

| Ever pregnant 2002 | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.02 (0.15) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Ever pregnant 2005 | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| First pregnancy 2002-2005 | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Used contraception 2005 | 0.85 (0.36) | 0.52 (0.50) | 0.95 (0.23) | 0.85 (0.36) | 0.78 (0.42) | 0.96 (0.19) |

| Used condom 2005 | 0.74 (0.44) | 0.32 (0.47) | 0.78 (0.42) | 0.83 (0.38) | 0.75 (0.43) | 0.73 (0.46) |

| Ever married 2002 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Ever married 2005 | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Married or cohabiting 2005 | 0.01 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.21) | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Schooling | ||||||

| Enrolled 2002 | 0.95 (0.21) | 0.92 (0.27) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.94 (0.23) | 0.89 (0.31) | 1.00 (0.00) |

| Enrolled 2005 | 0.77 (0.42) | 0.51 (0.50) | 0.81 (0.40) | 0.79 (0.41) | 0.49 (0.50) | 0.82 (0.39) |

| Dropped out 2002-2005 | 0.19 (0.39) | 0.35 (0.48) | 0.13 (0.34) | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.41 (0.49) | 0.03 (0.17) |

| Grades completed in 2002 | 7.48 (1.38) | 8.07 (1.21) | 8.08 (0.97) | 6.93 (1.60) | 7.71 (1.29) | 8.25 (1.14) |

| Grades completed in 2005 | 9.65 (1.53) | 10.1 (1.60) | 10.9 (0.89) | 9.35 (1.66) | 9.55 (1.91) | 11.1 (0.90) |

| Literacy/numeracy score | -0.49 (0.80) | 0.01 (0.78) | 1.05 (0.68) | -0.60 (0.83) | 0.02 (0.86) | 1.26 (0.60) |

| Household characteristics | ||||||

| Household income per capita | 398 (503) | 940 (897) | 4036 (2837) | 429 (657) | 967 (1022) | 3957 (2587) |

| Log income per capita | 5.52 (0.96) | 6.49 (0.88) | 8.04 (0.81) | 5.58 (0.94) | 6.47 (0.93) | 8.08 (0.66) |

| Household shock 2002-2005 | 0.22 (0.42) | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.02 (0.15) | 0.18 (0.39) | 0.14 (0.34) | 0.06 (0.25) |

| Mother's highest grade | 8.40 (2.96) | 8.74 (2.92) | 12.4 (2.00) | 8.70 (2.87) | 8.89 (2.73) | 12.7 (1.83) |

| Father's highest grade | 7.67 (3.85) | 9.11 (3.15) | 13.0 (2.15) | 7.52 (3.88) | 9.14 (3.27) | 12.9 (1.87) |

| Living with mother, 2002 | 0.70 (0.46) | 0.82 (0.39) | 0.94 (0.23) | 0.75 (0.44) | 0.80 (0.40) | 0.97 (0.18) |

| Living with father, 2002 | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.54 (0.50) | 0.76 (0.43) | 0.42 (0.50) | 0.58 (0.49) | 0.80 (0.40) |

| Household shock missing | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.08 (0.28) | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.12 (0.32) | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.19 (0.40) |

| Mother's grade missing | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.08 (0.27) | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.09 (0.29) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Father's grade missing | 0.42 (0.49) | 0.34 (0.47) | 0.11 (0.32) | 0.42 (0.49) | 0.28 (0.45) | 0.06 (0.23) |

| Sample size | 321 | 358 | 83 | 254 | 314 | 88 |

Note: Standard deviation in parentheses. Sample is restricted to those who were successfully followed from 2002 to 2005. Sexual debut, pregnancy, and dropping out are conditional on not having had sex in 2002, not having been pregnant in 2002, and being in school in 2002, respectively. Contraception use is at last sex, conditional on having had sex. Household income per capita in rands per month in 2002. Household shock defined in text.

The second outcome we analyze in our regressions is having a first pregnancy between 2002 and 2005. As seen in Table 5, only 2% of our female respondents aged 14-16 had experienced a pregnancy in 2002. The percentage who have a pregnancy between 2002 and 2005 is 21% for both African and coloured females, in spite of the much higher rates of sexual debut for Africans. Very few boys report having made a girl pregnant between 2002 and 2005 – 3% for Africans, 7% for coloureds, and 0% for whites. We do not have a great deal of faith in the boys' reports of having made a girl pregnant, but we include males in the regressions for completeness.

Although we do not include it in the regressions, we report the proportion married in 2002 and 2005 in Table 5. By 2005 only 1% of African females and 3% of coloured females report being married, although 23% of both groups report having been pregnant (with almost all pregnancies leading to a birth). This is consistent with the results in Table 3 suggesting that virtually all teen pregnancies are non-marital for both Africans and coloureds. Broadening the definition to include cohabitation, only 1% of African females and 5% of coloured females in this cohort were currently married or cohabitating in 2005. These results suggest that the fact that the transition from sexual activity into pregnancy is faster for coloured girls than for African girls is not driven by differences in marriage or cohabitation.

Table 5 also includes measures of contraceptive use. The first measure is whether respondents used a contraceptive method in their last sexual intercourse. Among whites contraception is almost universal, with 95% of females and 96% of males reporting that they used some method of contraception in their last sexual intercourse. Contraceptive use is also very high among Africans with no gender difference (85% for both males and females). Coloured females reported the smallest level of contraceptive use of all groups (52%) while 72% of coloured males reported having used a contraceptive method in their last sexual intercourse. Condoms use is highest among African males (83%), but is widespread among the majority of all groups with the notable exception of coloured females (32%). As shown in Dinkelman et al. (2007), CAPS data indicate an increase in condom use between 2002 and 2005.

The third outcome in our regressions is dropping out of school between 2002 and 2005, conditional on having been in school in 2002. Those who complete Grade 12 between waves are considered as not having dropped out, whatever their educational status in 2005. As seen in Table 5, the percentage who drop out ranges from 3% for white males to 41% for coloured males. Although coloured dropout rates are higher than African dropout rates, coloured grade attainment in 2005 is higher than African grade attainment for both males and females. The persistent large racial differences in schooling outcomes are clearly evident – the gap between white and African grade attainment in 2005 is 1.3 grades for females and 1.8 grades for males.

Scores on the literacy and numeracy evaluation demonstrate even more striking differences in the amount of learning acquired by 2002. These are standardized scores, with mean zero and standard deviation one for the full CAPS young adult sample. African females scored 0.5 standard deviations below coloured females and 1.5 standard deviations below white females, with even larger racial differences for males. As shown in Lam et al. (2007), these scores are strong predictors of grade advancement through secondary school between 2002 and 2005. We include them in our regressions to see if they are associated with sexual debut, pregnancy, and dropping out of school.

Table 5 also documents the enormous inequality that persists in post-apartheid South Africa and which provides an important backdrop for our analysis. Per capita household income (measured in 2002) for Africans is only about half the income of coloureds and about 10% of the income of whites, an indication of the enormous persistent racial gap in income. African youth are also much more likely to live in households that experience an economic shock. We define households as experiencing a negative shock if they report the death of household member, job loss, marital disruption, or loss of a grant or remittance between 2002 and 2005 and if the financial impact of this shock was described as moderate or large. The percentage of female respondents living in a household that experienced a negative shock is 22% for Africans, 15% for coloureds, and 2% for whites. This shock can only be defined for households interviewed in Wave 3, so it is missing for the roughly 10% of our respondents for whom we use Wave 4 data to construct 2005 outcomes. Looking at parental schooling in Table 5, African youth have parents with about four years less schooling than whites.8

Table 6 presents results of probit regressions in which the dependent variable indicates sexual debut, pregnancy, or school dropout between 2002 and 2005.9 Results are estimated separately for males and females, using the sample of respondents who were aged 14-16 in 2002. For each set of regressions the first row shows the marginal effect of the variable, evaluated at the mean, and the second row shows robust (Huber-White) standard errors in brackets.10 Given the rapid changes associated with age between age 14 and 20, we control for age with a quadratic function of age in months. We also include a variable for the number of months between the 2002 and 2005 interviews, since the length of this interval can vary across respondents by several months and since longer periods of exposure will lead to increased probability of sexual debut, pregnancy, and school dropout.

Table 6. Marginal effects from probit regressions for sexual debut, pregnancy, and dropping out of school between 2002 and 2005, CAPS respondents aged 14-16 in 2002.

| Female | Male | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Sexual debut 2002-2005 | First pregnancy 2002-2005 | Dropped out 2002-2005 | Sexual debut 2002-2005 | First pregnancy 2002-2005 | Dropped out 2002-2005 |

| Enrolled 2002 | -0.173 [0.12] | -0.303*** [0.11] | -0.192* [0.11] | -0.119 [0.073] | ||

| Grades completed in 2002 | 0.0657** [0.026] | -0.0776*** [0.029] | -0.0191 [0.018] | 0.0796*** [0.023] | 0.0302 [0.021] | -0.0365** [0.016] |

| Literacy/numeracy score | -0.0746** [0.035] | 0.0407 [0.042] | -0.101*** [0.022] | -0.0652** [0.033] | -0.0296 [0.023] | -0.0614*** [0.023] |

| Age in months since age 14 | 0.0178** [0.0087] | 0.00647 [0.012] | 0.00929* [0.0055] | 0.00911 [0.0087] | -0.00121 [0.0069] | 0.00651 [0.0059] |

| Age in months squared (*1000) | -0.311 [0.24] | 0.00352 [0.30] | -0.137 [0.14] | -0.0195 [0.24] | 0.0199 [0.17] | 0.0349 [0.16] |

| Coloured | -0.353*** [0.054] | 0.346*** [0.067] | 0.270*** [0.040] | -0.287*** [0.057] | 0.0985*** [0.037] | 0.319*** [0.048] |

| White | -0.175** [0.087] | -0.234* [0.14] | 0.540*** [0.13] | -0.0673 [0.097] | 0.215 [0.15] | |

| Log household income per capita | -0.0108 [0.029] | -0.00416 [0.034] | -0.0693*** [0.019] | -0.0296 [0.030] | 0.0155 [0.024] | -0.0599*** [0.023] |

| Household shock 2002-2005 | 0.110* [0.065] | 0.137* [0.073] | 0.103** [0.049] | 0.0681 [0.067] | -0.0473 [0.040] | -0.0304 [0.041] |

| Mother's highest grade | 0.0151 [0.0099] | -0.00677 [0.013] | -0.00196 [0.0063] | -0.0122 [0.011] | 0.00667 [0.0083] | 0.00209 [0.0067] |

| Father's highest grade | -0.0333*** [0.0096] | -0.00661 [0.012] | -0.0147** [0.0064] | -0.0178* [0.0092] | -0.00799 [0.0071] | -0.0102 [0.0064] |

| Living with mother, 2002 | -0.0622 [0.064] | 0.00347 [0.072] | -0.0401 [0.045] | 0.0516 [0.069] | 0.0690* [0.039] | -0.0343 [0.057] |

| Living with father, 2002 | -0.110* [0.061] | 0.0122 [0.079] | 0.0889** [0.039] | -0.111* [0.062] | 0.0395 [0.049] | -0.0143 [0.047] |

| Observations | 638 | 388 | 634 | 542 | 297 | 539 |

Robust standard errors in brackets.

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%.

First pregnancy is conditional on having had sex by 2005. Regression also includes dummy variables to indicate missing values for mother's schooling, father's schooling, and household shock.

Looking at the regressions for sexual debut, we see that the estimated marginal effect of being enrolled in school in 2002 on sexual debut by 2005 is negative for both males and females, though it is not statistically significant for females. Since enrollment rates were well over 90% in 2002, we have limited statistical power to estimate this effect, and it is in any event not going to play an important role in driving sexual debut.

One of the intriguing results in Table 6 is that the number of grades completed has a significant positive effect on sexual debut for both males and females. These positive effects of schooling on sexual debut, controlling for age, are surprising, since we might expect that young people who are ahead of their age group in school would be less likely to become sexually active. The estimates imply that a girl with one additional grade completed in 2002, given her age, is 6.6 percentage points more likely to sexually debut by 2005. The effect for boys is slightly larger at 8 percentage points. This result is very robust to alternative specifications. One possible interpretation is that young people who are ahead of their cohort in school interact with an older and more sexually active group of girls and boys. Given the wide range of grade-forage, especially in African schools, students of a given age may have very different aged classmates. As shown in Table 4, African girls who were age 16 in 2002 were distributed from Grade 7 to Grade 12, implying large differences in the age distribution of their classmates. Adolescents could be influenced by the behavior of older same-sex peers and by interactions with older opposite-sex peers (the vast majority attend mixed-sex schools).

While further research is required to determine whether the apparent positive effect of higher grade attainment on sexual debut is due to peer effects, evidence in support of this interpretation is provided by the fact that the impact of current grade becomes less positive, though still positive and significant, when we remove the literacy and numeracy test score from the regression (result not shown). Our interpretation of this is that there are offsetting effects from being ahead in school. On the one hand, girls who are doing better in school and anticipate good schooling outcomes in the future may be less likely to become sexually active. On the other hand, they interact with older girls and boys who are more sexually active, increasing the probability that they become sexually active. When we control for previous schooling performance with our literacy and numeracy test scores, we control for some of the first effect, leaving the second effect to become more pronounced. Additional evidence in support of this interpretation is that when we estimate the probit separately by race (not shown), the positive effect of schooling on sexual debut is largest for the African sample, the group in which there is the largest variation in grade for age. The coefficient is positive for coloureds and whites, but it is smaller in magnitude and is not statistically significant. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to rigorously test the possibility that peer effects explain the positive effect of grade attainment on sexual debut, we think it is an interesting hypothesis that merits further research.

Turning to the literacy and numeracy evaluation (LNE), we estimate significant negative effects of the LNE score on sexual debut for both males and females. A one standard deviation increase in the LNE score implies a 7 percentage point reduction in the probability of sexual debut for both girls and boys, controlling for age and grade. This result could have a number of interpretations. It may indicate that young people who are doing better in school and anticipate better performance in the future want to delay sexual activity in order to avoid the risk of pregnancy or disease that might interfere with their future opportunities. A slightly different interpretation is that some young people are more focused on schooling than on social interactions, with the result that they accumulate more knowledge while also being less likely to become sexually active. Another interpretation is that young people who are less attractive end up with fewer friends who are potential sexual partners, with the result that they devote more time to school and homework.

We include a quadratic in age, where age is measured in months since turning age 14. The marginal effect on the linear age variable implies that there is a 1.8 percentage point increase from one additional month of age, evaluated at age 14. This implies a 21 percentage increase when the respondent was 15 rather than 14 in 2002. The negative coefficient on the age squared term implies a slight decline in the impact of age at older ages. Although it is not statistically significant, we include it in the regression in order to permit a flexible relationship between age and our outcome variables.

The marginal effects for the dummy variables for coloureds and whites (African is the omitted category) confirm patterns shown in Table 5 and in the previous graphs. Coloured and white girls are less likely to become sexually active in their teenage years than African girls, with similar racial differences among males. The regression results indicate that after controlling for prior schooling outcomes, household income, and parental schooling, coloured girls are 35 percentage points less likely than African girls to sexually debut between 2002 and 2005. White girls are 17 percentage points less likely to sexually debut than African girls.

The next set of variables in Table 6 represent household characteristics that may affect sexual debut. The log of household income per capita has a negative coefficient in both the female and male regressions, but is not statistically significant. We estimate a statistically significant positive effect of a household shock on female sexual debut. The result implies that girls living in a household that experienced a negative shock between 2002 and 2005 are 11 percentage points more likely to become sexually active during that period. Dinkelman, Lam, and Leibbrandt (2007) find using CAPS data that negative shocks are also associated with an increase in women's risky sexual behavior such as having multiple sex partners.11

The coefficient on mother's schooling in the female sexual debut regression is positive but statistically insignificant. The impact of father's schooling on sexual debut is negative and statistically significant for both girls and boys, implying that one additional grade of schooling of the father reduces the probability of female sexual debut by 3 percentage points. We include dummy variables to indicate whether the respondent lived with their mother and father in 2002. The coefficients on both variables imply that those who were living with parents were less likely to sexually debut, although only the effect of living with the father is statistically significant.12

The regressions for the second outcome – having a first pregnancy (or making a girl pregnant) between 2002 and 2005 are conditional on not having been pregnant in 2002 and having had sex by 2005. We estimate a significant negative effect of being enrolled in school in 2002. Controlling for other variables, girls who were enrolled are 30 percentage points less likely to have a pregnancy than the small fraction of girls who were not enrolled in 2002. The effect of grade attainment is negative for girls, with one additional grade in 2002 implying an 8 percentage point decline in the probability of pregnancy. When we estimate this regression without conditioning on sexual debut (not shown), the estimated impact of grade attainment is not significant for girls. While girls who are ahead in school are more likely to become sexually active, they are less likely to get pregnant once they become sexually active, with the net effect that there is no overall relationship between grade attainment and pregnancy across all girls.

The estimated impact of the LNE score on pregnancy is not statistically significant for either girls or boys. We estimate a large impact being coloured on the probability of pregnancy for both boys and girls, consistent with the patterns shown above. While coloured girls are less likely to become sexually active than African girls, those who do become sexually activity are 35 percentage points more likely to get pregnant than African girls, controlling for other variables in the regression. We estimate a statistically insignificant effect of income on pregnancy for both boys and girls, but estimate a significant positive impact of an economic shock for girls. Sexually active girls in households with negative household shocks have a 14 percentage point higher probability of getting pregnant between 2002 and 2005.

The third outcome presented in Table 6 is dropping out of school between 2002 and 2005. These regressions are restricted to the sample that was enrolled in school in 2002. One of the most important results in this regression is the impact of the literacy and numeracy evaluation. Girls and boys with higher LNE scores are significantly less likely to drop out between 2002 and 2005. For girls, a one standard deviation increase in the score is associated with a 10 percentage point decline in the probability of dropping out of school.

We estimate significant positive effects for the coloured dummy for both boys and girls. Holding the other variables constant, coloured girls are 27 percentage points more likely to drop out, and coloured boys are 32 percentage points more likely to drop out than their African counterparts. We also estimate a significant positive impact of being white on the probability of dropping out for girls. While this is surprising, it is consistent with results estimated by Lam et al. (2007), who show that the literacy and numeracy test scores and household income can more than explain the racial differences in progress through school.

Household income and income shocks are both associated with dropping out. The estimated marginal effect of household income is significantly negative for both males and females. The coefficients imply that a 10% increase in per capita household income is associated with a 0.7 percentage point decrease in the probability of dropping out for girls and a 0.6 percentage point decrease for boys. Household shocks have a significant negative effect on dropping out for females, implying a 10 percentage point increase in the probability of dropping out. The effect of the shock is not significant for males for any outcome. The smaller impact of household shocks on boys' dropout behavior versus girls' is consistent with some previous research, including Duryea et al.'s (2007) analysis of the impact of unemployment shocks in Brazil.

In Table 6 we did not included sexual debut or pregnancy in the dropout equation (or dropout in the sexual debut or pregnancy equation) since we consider our three outcomes to be jointly determined. While we know that girls who drop out are more likely to get pregnant, it is not possible to tell if one causes the other or if both are determined by some common unobserved variable. With this important caveat in mind, it is nonetheless interesting to look at dropout regressions in which we include sexual debut and pregnancy as independent variables. Table 7 presents dropout regressions estimated separately for African and coloured respondents (we omit whites because of the small sample size and the small number of pregnancies). The regressions confirm that after controlling for variables such as baseline schooling, LNE scores, and household income, girls who become sexually active between 2002 and 2005 are less likely to stay in school. The “effect” of both sexual debut and pregnancy on school dropout is larger for coloureds than for Africans. Coloured girls who become pregnant are 22 percentage points more likely to drop out, while African girls who become pregnant are 12 percentage points more likely to drop out. This confirms that the racial differences shown in bivariate relationships above continue to hold when we control for other variables. The impact of pregnancy on dropout cannot be estimated for African boys because only a small proportion report getting a girl pregnant and it perfectly predicts dropout.

Table 7. Marginal effects from probit regressions for dropping out of school between 2002 and 2005, CAPS respondents aged 14-16 in 2002.

| Female | Male | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | African | Coloured | African | Coloured |

| Sexual debut 2002-2005 | 0.136*** [0.0363] | 0.189** [0.0743] | 0.0554 [0.0405] | 0.224*** [0.0729] |

| Pregnancy 2002-2005 | 0.120* [0.0649] | 0.223** [0.0914] | 0.407** [0.204] | |

| Grades completed in 2002 | -0.0385** [0.0179] | -0.0243 [0.0294] | -0.0245* [0.0133] | -0.0716* [0.0412] |

| Age in months since age 14 | -0.0106* [0.00594] | 0.0153* [0.00813] | 0.0139** [0.00675] | -0.0114 [0.0111] |

| Age in months squared (*1000) | 0.355** [0.155] | -0.367* [0.221] | -0.318 [0.205] | 0.580* [0.310] |

| Literacy/numeracy score | -0.01 [0.0201] | -0.152*** [0.0392] | 0.00595 [0.0217] | -0.0841* [0.0487] |

| Log household income per capita | 0.00966 [0.0184] | -0.0940*** [0.0351] | -0.0157 [0.0222] | -0.110** [0.0472] |

| Household shock 2002-2005 | 0.0475 [0.0478] | 0.102 [0.0766] | -0.0458 [0.0281] | -0.0518 [0.0865] |

| Mother's highest grade | 0.00639 [0.00686] | -0.00839 [0.0104] | -0.000364 [0.00666] | 0.00195 [0.0127] |

| Father's highest grade | -0.00444 [0.00637] | -0.00887 [0.0106] | -0.00165 [0.00678] | -0.0308** [0.0124] |

| Living with mother, 2002 | 0.0579** [0.0282] | -0.111 [0.0745] | -0.0663 [0.0809] | -0.101 [0.116] |

| Living with father, 2002 | -0.0233 [0.0415] | 0.182*** [0.0659] | 0.0353 [0.0509] | 0.0384 [0.0920] |

| Observations | 204 | 283 | 138 | 229 |

Robust standard errors in brackets.

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%.

First pregnancy is conditional on having had sex by 2005. Regression also includes dummy variables to indicate missing values for mother's schooling, father's schooling, and household shock.

Table 6 also allows us to see how variables interact with race. Particularly interesting is the fact that the impact of the LNE score and household income on dropping out is much larger for coloureds than for Africans. This is consistent with the results of Lam et al. (2007), who argue that it is a reflection of the fact that African schools do a poor job of matching actual learning with measured performance and grade promotion. African students remain in school even when they are failing grades, while coloured students tend to drop out when they fail a grade.

Conclusions and Discussion