Abstract

Objective

To examine physician communication associated with prognosis discussion with cancer patients.

Methods

We conducted a study of physician-patient communication using trained actors. Thirty-nine physicians, including 19 oncologists and 20 family physicians participated in the study. Actors carried two hidden digital recorders to unannounced visits. We coded recordings for eliciting and validating patient concerns, attentive voice tone, and prognosis talk.

Results

Actor adherence to role averaged 92% and the suspected detection rate was 14%. In a multiple regression, eliciting and validating patient concerns (β=.40, C.I. = 0.11-0.68) attentiveness (β=.32, C.I. = 0.06-0.58) and being an oncologist vs. a family physician (β=.33, C.I. = 0.33 - 1.36) accounted for 46% of the variance in prognosis communication.

Conclusion

Eliciting and validating patient concerns and attentiveness voice tone is associated with increased discussion of cancer patient prognosis as is physician specialty.

Practice Implications

Eliciting and validating patient concerns and attentive voice tone may be markers of physician willingness to discuss emotionally difficult topics. Educating physicians about mindful practice may increase their ability to collect important information and to attend to patient concerns.

Keywords: cancer, patient-centered communication, voice tone, prognosis

1. Introduction

We conducted a pilot study to examine the discussion of prognosis during oncology visits. We used actors to portray stage IV lung cancer patients seeking a new consultation. While guidelines exist for discussing prognosis with patients [1,2], there is no firm evidence supporting any one approach. [3]

Researchers have found that patients prefer a realistic and hopeful style when disclosing prognosis. Hope is conveyed partly by discussing all the treatment options.[4]

Cancer patients in Western cultures report a preference for knowing their diagnostic findings, prognosis, and probability of successfully treating their disease.[5,6] Not all cultures endorse such a preference; physicians from non-western cultures may be more reluctant to disclose prognostic information than western physicians. [7] Others have described the practical difficulties of determining if a specific cancer patient really wants to know his or her prognosis.[8] It is common for patients not to understand their prognosis, which may hinder patient and clinician action and decision-making. [9] Both patient and physician factors affect prognosis discussion in medical encounters.[10]

Prognosis discussions are hampered by the different focus of the patient and the physician.[11] Patients are focused on the impact of cancer on their lives and their discomfort and pain. Physicians, by contrast, are focused on the illness, particularly on its progression and treatment. In this study, we controlled for patient characteristics by using SPs to present a consistent message from patients about their desire for information about prognosis. We hypothesized that patient-centered communication (eliciting and validating) would be associated with prognosis discussions. Eliciting and validating is a multi-faceted construct that includes physicians' eliciting and understanding patients' perspective, understanding the patients' psychosocial context, developing a shared understanding of the problem, and sharing decision-making power if patients desire.[12] Eliciting and validating has been found to be associated with greater satisfaction with visits[13], reduced health care costs [14], more appropriate prescribing of anti-depressants.[15] Eliciting and validating is also hypothesized to be an outcome of mindful practice,[16] thus we hypothesized that an attentive posture in session would also be associated with greater eliciting and validating and with prognosis communication. We assessed attentiveness by rating warmth, concern, worry, and openness as conveyed by physician voice tone.

2. Methods

Standardized patient (SP) methodology has been extensively used in primary care research [13-14, 17-19] but, to our knowledge, has not been used to examine oncology patient visits. SPs were trained to portray a stage IV lung cancer patient. We developed a model transcript complete with biographical data for training the SPs to adhere to role. Purdue University and Indiana University human subjects review boards both approved the study. After we obtained physician consent, we requested the name of one staff person in each office to be a confederate for the study. Our research staff communicated with the confederates to arrange unannounced visits with physicians. We sent a complete medical record to the physician prior to the visit through the confederate. The purpose of the medical record was to make the SPs' diagnosis and stage of cancer believable. SP visits were conducted from February through August 2008. All three SPs were male. Physicians were sent a fax 3 weeks after the visit asking if they suspected at the time of the visit that they were seeing an SP. While making visits, SPs carried two digital recorders that fit into their pockets in order to record the visit surreptitiously. SPs turned on the recorders in their cars before they approached the physicians' offices to avoid detection.

The SPs cover story was that he had moved from another part of the country to live closer to his daughter. The SP medical record attested to the SP's previous treatment for lung cancer. SPs were coached to give information about themselves in response to questions, but not to give too much unsolicited information. The SP's background was that he had been a manager of a small motel until he became ill. He had first gone to the physician for care because of back pain, which turned out to be lung cancer. He had radiation treatment for his cancer, but no chemotherapy or surgery. Because he felt better following the radiation treatment, he was not fully aware that the cancer had not been cured. He stated that he had not been told his diagnosis when he was first treated. He presented to the physician with new pain in the front of his chest that he was unaware was likely a new metastasis of his cancer.

The purpose of this scenario was to invoke a sense of urgency for the physicians to treat or refer the SP. Because the SP was both unaware of his prognosis and the likelihood that his new pain was indicative his cancer had metastasized further, physicians would need to explain these facts to the SP in order to plan treatment or, to refer him to an oncologist in the case of primary care physician visits,.

2.1. Research Participants

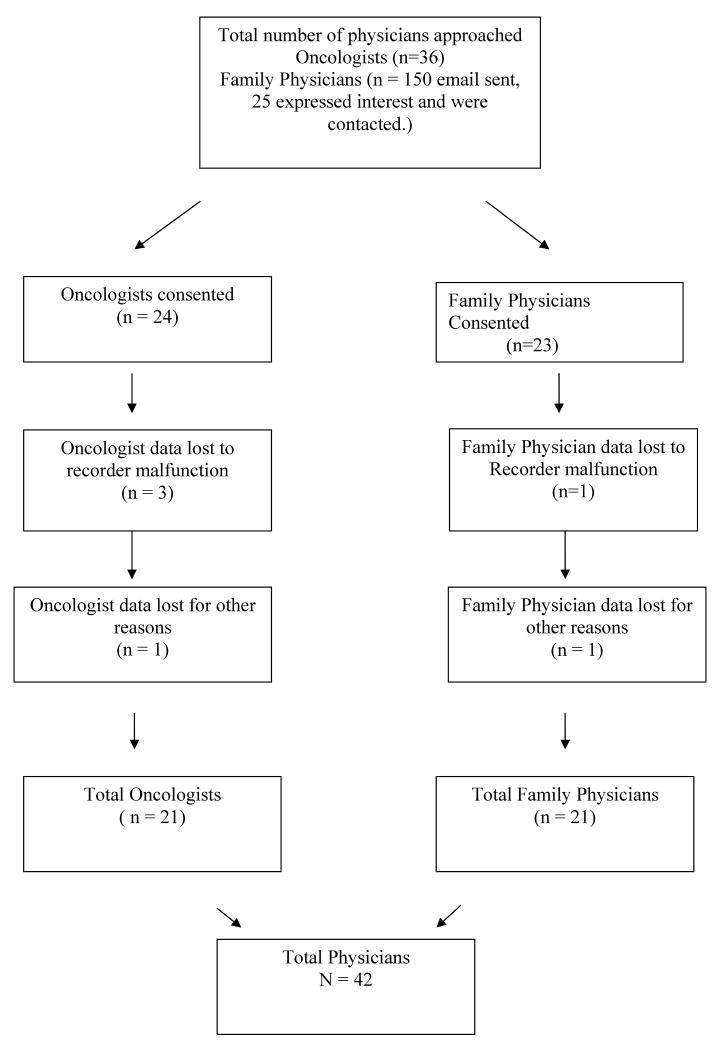

We recruited 46 physicians, 23 oncologists and 23 family physicians, through the Indiana University Family Practice Research Network (INET) and through senior oncologists at Indiana University Cancer Center. Figure 1 is a flowchart of our sample recruitment. We contacted 36 oncologists to recruit our 24, giving us a 67% response rate. One-hundred and fifty emails were sent to family physicians, twenty-five expressed interest in the study, and twenty-three were consented for a response rate of 15%. Physicians averaged 48.1 (SD=9.2) years of age. Seventy-one percent of all physicians were male. Sixty-eight percent of all the physicians were of European ancestry. Table 1 shows the percentages and means by type of physician. There were no significant differences between oncologists and family physicians on these demographic variables.

Figure 1. Flow of Participants through the Study.

Table 1.

Physician Demographics

| Variable | Physicians % / M SD |

Oncologists % / M SD |

Family Physicians % / M SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 71% | 75% | 67% |

| European Ethnicity | 68% | 60% | 76% |

| Age (M SD) | 48.1 (9.2) | 47.7 (8.0) | 48.5 (10.5) |

Using χ2 We found no significant differences between oncologists and family physicians.

2.2. Measurement Instruments

2.2.1. Measures of patient-centered communication

Eliciting and Validating Patient Concerns

We measured physicians' eliciting and validating of patient concerns using Component I of the Measure of Patient-Centered Communication.[20] In previous studies, eliciting and validating patient concerns has proved to be the most reliable and valid component of the measure.[13] Coders listened to audio recordings of the visit and coded for the presence of physician behaviors of preliminary exploration, further exploration, validation, or cut off in response to each issue discussed by the SP and the physician. Two graduate students and two undergraduate students coded the recordings. Twenty of the recordings were coded by two different coders for reliability purposes. We had acceptable reliability; the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.88. Scoring ranged from 1 – 5 depending on the depth of discussion. Table 2 shows a portion of a coding sheet for eliciting and validating. Physician responses to each item were coded a 1 for preliminary exploration, another 1 point for further exploration, and another 3 points if the response also included validation of the patient's experience. A cut off resulted in a loss of 1 point from the score. Table 3 also lists all the items coded for Component 1. We report average scores of the 1-5 scale rather than converting them to percentage as has been done in previous research. [20] We conducted an item analysis and found that by eliminating 7 items from the original 19, the scale had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.78.

Table 2.

Response Categories for Coding Eliciting and Validating Concerns and Prognosis Discussion

| Preliminary Exploration (PE) | Further Exploration (FE) | Validation (VAL) | Cut Off (CO) | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scoring Protocol | 0 = none | 0 = none | 0 = none | 0 = none | 1 = PE, FE, & CO |

| Each item was scored on scale | 1 = occurred | 1 = occurred | 1 = occurred | 1 = occurred | 2 = PE or FE |

| 3 = PE & FE, or | |||||

| 3 = PE, FE, VAL, & CO | |||||

| 4 = PE & VAL | |||||

| 5 = PE, FE, & VAL |

Preliminary Exploration = A PE is scored when the physician acknowledges the patients concerns by saying “uh huh” or any other simple statement.

Further Exploration = FE is scored when the physician encourages the patient to tell him or her more about the concern.

Validation = VAL is scored when the physician underscores or supports the patient about his or her concerns by using such phrases as “I'm glad you came to see me about this” or “I can see why you are worried about this.”

Cut-Off = CO is scored when the patient talks about an issue but the physician responds by changing the topic rather than exploring the patient's concerns.

Table 3.

Eliciting and Validating Items

| Item | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Inquiries/Discussion about mood/depression | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 2. Inquiries/Discussion about cancer's impact on life | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.0 - 4.0 |

| 3. Inquiries/Discussion about sleep | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 4. Inquiries/Discussion about weight loss | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 5. Inquiries/Discussion about appetite | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 6. Inquiries/Discussion about previous physicians | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 7. Inquiries/Discussion about current medications | 2.3 | 1.2 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 8. Inquiries/Discussion about alcohol use | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 9. Discusses working status | 1.9 | 1.4 | 0.0 - 4.0 |

| 10. Discusses marital status | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 11. Treatment Plan: discuss medications for treatment | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 12. Ask about ADLs and IADLs | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| Additional items dropped from scale* | |||

| 13. Inquiries/Discussion about medical problems unrelated to cancer | 2.7 | 0.8 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 14. Conducts a physical exam | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 15. Inquiries/Discussion about smoking | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 16. Discusses any at-risk exposure to carcinogens | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 17. Recommended change in pain medications | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 18. Cancer: Scans done since treatment | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 19. Cancer: radiation done to back | 2.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 20. Treatment Plan: PET scan or some other scan | 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 21. Treatment Plan: Discuss referral for Radiation Oncologist | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 22. Treatment Plan: Other Blood Tests | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

These behaviors happened either so infrequently that we were unable to code reliably or they did not correlate with the total score and their removal improved Cronbach's alpha.

Voice Tone

We measured attentiveness voice tone by rating four separate factors: warmth, concern, worry, and openness for each physician on a 1 – 7 scale. The intraclass correlation for each individual factor ranged from 0.59 to 0.87 and mean of the four items had an ICC of 0.85. The four items also strongly correlated with each other and produced a single factor with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.86.

2.2.2 Assessing prognosis communication

We assessed prognosis communication by creating items based on the components of the SPIKES protocol for delivering bad news. [1] Table 4 shows the 10 items that we used to code prognosis communication along with 6 items that occurred so infrequently we could not code them reliably. These items assess physicians' behaviors that communicate diagnostic information and treatment options (palliative care) that are likely to be offered to a stage IV lung cancer patient. We coded these items using the same physician response coding that we used for coding eliciting and validating (see Table 2). The intraclass correlation coefficient for the prognosis scale was 0.81 and the Cronbach's alpha for the 10 out of 16 items remaining in the scale was 0.80. We also created a prognosis frequency variable so that we could examine the number of prognosis items discussed. While eliciting and validating patient concerns and prognosis communication were coded using the same physician response code, they remain separate constructs because they coded very different communication behavior.

Table 4. Prognosis Communication Items.

| Item | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MD asks if patient wants to know more about their diagnosis | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 2. Discussing the meaning and potential change in the diagnosis | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 3. MD asks if patient wants to know the prognosis | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 4. Assessing the patient's understanding of his/her prognosis | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 5. Involving family or friends of the patient – “Is there someone here you would want to hear more about your prognosis with you?” | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 6. Involving family or friends in the decision-making – “do you want me to call them?” | 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 7. Discussing likelihood that any further treatment will be effective | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 8. Discussing transition from active to palliative treatment | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| 9. Offering contact information for questions that may come up. | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

| Additional items dropped from scale* | |||

| 1. Assessing patient's knowledge of state of disease. | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 2. Tells patient their diagnosis or prognosis without asking whether they want to know first | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.0 3.0 |

| 3. Does the physician warn the patient that bad news is coming | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 - 2.0 |

| 4. Does the physician preface his or her remarks with, “I am sorry to tell you …” | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.0 - 4.0 |

| 5. Discussing end of life issues e.g. DNR orders, Power of Attorney | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.0 - 5.0 |

| 6. Physician gives estimate of survival time | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.0 - 3.0 |

These behaviors happened so infrequently that we were unable to code reliably or they did not correlate with the total score and their removal improved Cronbach's alpha.

2.2.4 Physician survey

Physicians were faxed a short questionnaire to inform them that they had seen an SP and to assess whether they suspected that they had seen an SP. If they did suspect, they were asked when they knew that had seen an SP, whether it was during or after the visit, and how they found out (e.g., staff told them, SP behavior, or closed practice.).

2.2.5 Adherence of SPs to role

We coded SPs' adherence to role by creating a coding system based on the role transcript that we had used to train the SPs. We extracted from the transcript 20 items that covered the most important aspects of the role. We used a 1 – 5 point coding system for each section of the transcript with 1 being inaccurate or not portrayed at all to 5 being very accurate portrayal of that part of the role. Undergraduate research assistants rated each major item of role content on this 1-5 scale and we calculated the overall percentage of adherence by dividing the mean score by 5.

2.3. Statistical analysis

We examined study variables for their adherence to assumptions of normality and for the presence of outliers. No variables violated the assumptions. We then conducted correlation and regression analyses to examine which variables explained variance in prognosis communication.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 5 shows the means and standard deviations of the study variables. There was a non-significant trend for oncologists to engage in more Prognosis Communication (for both mean and frequency) with the SPs than family physicians. Physicians engaged in more eliciting and validating than prognosis communication (t = 5.07, p < .001). SP visits to physicians' offices averaged 30.32 (SD=12.90) minutes in length.

Table 5. Descriptive Statistics.

| Family Physicians | Oncologists | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range |

| Prognosis Communication | 7.7 | 5.4 | 0.0 - 23.0 | 11.7 | 7.3 | 0.0 - 27.0 ∼ |

| Prognosis Communication (FQ) | 3.2 | 2.1 | 1.0 - 8.0 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 1.0 - 9.0 ∼ |

| Eliciting & Validating | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 - 2.5 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 - 2.5 |

| Voice Tone: Attentive | 3.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 - 5.0 | 3.9 | 0.9 | 2.5 - 5.5 |

| Length of Visit (Minutes) | 32.1 | 13.0 | 15.0 - 72.5 | 28.2 | 13.3 | 9.5 - 56.0 |

Note: T-tests found no significant differences between groups except for a ∼ p < .10 for Prognosis communication and prognosis frequency. FQ = Frequency

3.2 Reliability and validity of SP role portrayal

The mean adherence level was 92% for all the visits. The level of prompted detection of visits reported by physicians was 14%. This high level of adherence and low detection rate indicates that our SP role and training was successful in presenting a cancer patient SP to community physicians and that the detection rate was similar to other studies.

3.2 Correlational analyses

Table 6 shows the correlations between study variables. Prognosis communication is correlated with eliciting and validating (r=.44, p<.005), significantly correlated with attentive voice tone (r=.50, p<.005), marginally correlated with length of visit (r=.28, p<.10), and marginally correlated with physician specialty (i.e., being an oncologist) (r=.31, p<.10). Note that though eliciting and validating were correlated with prognosis, they only share 19% of variance, which supports our contention that they are not measuring the same construct. Oncologists' score on prognosis was 11.7 (SD=7.3) compared to 7.7 (SD=5.5) for family physicians, but the difference was not quite significant (t=1.93, p = .06). Both oncologists and family physicians did discuss prognosis with oncologists addressing an average of 4.5 (SD=2.2) prognosis issues per session and family physicians discussing 3.4 (SD=2.1) prognosis issues per session (t=1.91, p = .06). Physician age, gender, and ethnicity were not significantly correlated with prognosis communication.

Table 6. Correlations of Study Variables.

| Prognosis Discuss | Eliciting Validate | Attentive | Length | Male | Age | Oncologist | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eliciting/Validating | 0.44** | ||||||

| Attentive | 0.50** | 0.33* | |||||

| Length of Visit (Minutes) | 0.28∼ | 0.32∼ | 0.14 | ||||

| Physician = Male | 0.01 | -0.10 | -0.10 | -0.09 | |||

| Physician Age | 0.01 | -0.09 | -0.27∼ | 0.09 | 0.13 | ||

| Physician = Oncologist | 0.31∼ | -0.28∼ | 0.14 | -0.16 | 0.02 | -0.05 | |

| Physician European Ethnicity | 0.04 | -0.01 | -0.03 | 0.16 | -0.28 | 0.39* | -0.25 |

p < .01

p < .05

p < .005

Attentive voice tone was correlated with eliciting and validating (r=.33, p<.05) and marginally with physician age, with younger physicians being rated as more attentive (r=.28, p<.10). Length of visit was also marginally correlated with eliciting and validating (r=.26, p<10). Physicians of European descent were more likely to be female than physicians from Asia or the Middle-East (χ2 = 4.28, p=.05).

3.4 Multiple regression analyses

Table 7 shows the results of a multiple regression analysis of voice tone, eliciting and validating patient concerns, physician demographics, and visit length on prognosis communication. Attentive voice tone (β = 0.32, p<.05), eliciting and validating patient concerns (β = 0.40, p<.005), and being an oncologist (β = 0.43, p<.005) were each associated with prognosis communication. The model accounted for 46% of the variance in prognosis communication.

Table 7. Regression of Prognosis Communication.

| Standardized Coefficients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | b | SE | 95% C.I. | β | 95% C.I. |

| Intercept | -10.01 | 3.91 | -2.06 - 0.02 | ||

| Attentive | 2.41 | 0.97 | 4.37 - 0.02 | 0.32 * | 0.06 - 0.59 |

| Eliciting/Validating | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.56 - 0.01 | 0.40 ** | 0.11 – 0.68 |

| Oncologist | 5.64 | 1.67 | 9.04 - 0.00 | 0.43 ** | 0.33 – 1.36 |

| Length in Minutes | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.22 - 0.16 | 0.18 | -0.01 – 0.03 |

p < .05

p < .005

R2 = 0.46

β = Standardized coefficients

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1 Discussion

Our findings support our hypotheses. In bivariate analysis, prognosis communication was significantly associated with attentiveness, eliciting and validating patient concerns, and the physician being an oncologist. In multivariate analysis, greater attentiveness, greater eliciting and validating patient concerns, and physician specialty were the only variables associated with greater prognosis discussion. We found that physicians on average discussed 4 out of 16 prognosis items. That oncologists gave more prognosis information than family physicians was expected given their training in diagnosing and treating cancer. However, most family physicians also discussed prognosis. In summary, physicians who used a more patient-centered communication style, who elicited and validated patients concerns and spoke with a warm engaging voice tone, engaged in more in depth prognosis discussions with patients.

Attentive voice tone was calculated for the means of ratings of physician warmth, concern, worry, and openness. Each item was rated on a 1-7 scale, with higher scores indicating a greater presence of each in the voice of the physician. Similar rating scales of voice tone have found correlations with patient satisfaction and health status.[21,22] Physician attentiveness with cancer patients is associated with higher patient satisfaction.[23] Our attentiveness measure is similar to the friendliness/warmth scale of the Roter Interaction Analysis Scale, which has been found to be associated with visit specific satisfaction.[24]

Attentive voice tone may be one characteristic of a communication style that invites conversations about difficult topics such as prognosis. Attentive voice tone may also be a marker for physician mindfulness – a state of a self-awareness characterized by purposeful attention to one's own thoughts and feelings in a non-judgmental fashion.[25] By calibrating one's own thoughts and feelings, a mindful practitioner is more present or attentive with his or her patients and more supple in their response to difficult emotions and challenging situations.[26] Future studies should examine the relationship between physician mindfulness and their ability to attend to patients' concerns.

Eliciting and validating was also associated with prognosis communication and significantly correlated with attentiveness. While we expected this result, it is important to emphasize that while the two measurement instruments used similar physician response codes, they each assessed a different construct because of the different items they coded. Eliciting and validating, which was measured primarily in the first half of the session when physicians were gathering information from the patient, shared 19% of its variance with prognosis and 12% of its variance in the multivariate model. While some of this variance is likely shared method variance, we would argue that most of it is probably because physicians who gather data about the patient at the beginning are likely to know the patient better and thus, if appropriate, be more willing to discuss prognosis issues with the patient.

Cancer patients who are not cognizant of their prognosis may elect to continue with treatment without an accurate understanding its benefits and burdens,[8] and may sacrifice the quality of life during their final days due to avoidable side-effects.[27]. Patients with advanced cancer treatment choices are further conditioned by their often overly optimistic prognoses.[28] Practitioners can influence patients' beliefs about the effects of treatment and thus reduce unnecessary suffering at the end of life. [28]

Physicians understandably try to offer hope to cancer patients.[8] However, a realistic perspective, including a small amount of “negative” information about the course of therapy, can help patients gain a more balanced perception of their prognosis and subsequently experience less anxiety and distress.[29,30] Oncologists rarely give negative information. For example, in one study of 51 oncologists, in only 15% of visits did oncologists state that the patient's disease course had not gone well. However, when physicians did state that the course of treatment was poor, there was greater concordance about prognosis between patient and physician. [28] Furthermore, not all patients want to have an in-depth discussion about their prognosis, [31] or may wish to address these issues indirectly,[8] -- especially those from non-European cultures.[7] In all these situations, physicians need to discern the needs and values of the patient and family before they deliver poor prognostic news. Such communication is the essence of patient-centered care.

4.2 Conclusion

Controlling for physician specialty, prognosis communication was associated with an attentive voice tone and communication characterized by eliciting and validating patient concerns. Physicians who communicate care and concern through their voice tone and who gather more information at the beginning of the session may show patients that they are interested and available to engage in discussions of sensitive emotional issues such as prognosis with their patients. Physicians, too, may feel more comfortable discussing prognosis when they have a greater understanding of patients' concerns.

4.3 Practice Implications

Most medical schools teach communication and medical ethics though few programs address communication about difficult topics such as disclosing terminal prognoses.[32] In a survey of oncologists, only 6% report that they have received formal training in delivering bad news.[33] Some physicians are afraid that they themselves will lose control in terms of emotions and professional and personal confidence, during a bad news consultation.[34] Giving bad news clearly raises existential issues for the physician as well as the patient and requires learning to be comfortable sitting with patients who are dying and tolerating emotional intensity. Physicians can be taught these skills successfully,[35] though not all attempts to improve physician communication skills are successful.[36] It is possible that mindfulness training may be an avenue for teaching physicians to be more attentive, to gather more information from patients, and to tolerate the existential issues involved in discussing prognosis with patients.[37] Such an approach warrants study.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by NCI grant # R21CA124913 to Dr. Shields

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr Epstein received honoraria from Merck for lectures relating to patient-physician communication. No products were discussed. No other potential conflicts of interest are reported.

I confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Baile WR, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES--A six-step protocl for delivering bad news: Application to the patients with cancer. The Oncologist. 2000;5:302–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clayton JM, Hancock KM, Butow P, Tattersall M, Currow DC. Clinical practice guidelines for communicating prognosis and end-of-life issues with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness, and their caregivers. Medical Journal of Australia. 2007;186:S77–S108. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, Lobb EA, Pendlebury SC, Leighl N, Mac Leod C, Tattersal MHN. Communicating with realism and hope: incurable cancer patients' views on the disclosure of prognosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:1278–88. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, Dimitry S, Tattersall MHN. Communicating prognosis in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1005–53. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassileth BR, Zupkis RV, Sutton-Smith K, March V. Information and participation preferences among cancer patients. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92:832–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-92-6-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, Saul J. Information needs of patients with cancer: results from a large study in UK cancer centres. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:48–51. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell JL. Cross-Cultural Issues in the Disclosure of Cancer. Cancer Practice. 1998;6:153–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006003153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helft PR. Necessary collusion: Prognostic communication with advanced cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:3146–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zapka JG, Carter R, Carter CL, Hennessy W, Kurent JE, Desharnais S. Care at the End of Life: Focus on Communication and Race. Journal of Aging and Health. 2006;18:791–813. doi: 10.1177/0898264306293614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinmetz D, Walsh M, Gabel LL, Williams PT. Family physicians' involvement with dying patients and their families. Attitudes, difficulties, and strategies. Archives of Family Medicine. 1993;2:753–60. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.7.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donabedian A. Aspects of Medical Care Administration: Specifying Requirements for Health Care. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Kravitz RL, Duberstein PR. Measuring patient-centered communication in Patient-Physician consultations: Theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1516–28. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiscella KM, Meldrum SM, Franks PM, Shields CG, Duberstein PP, McDaniel SH, Epstein RM. Patient Trust: Is It Related to Patient-Centered Behavior of Primary Care Physicians? Medical Care. 2004;42:1049–55. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein RM, Franks P, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Miller KN, Campbell TL, Fiscella K. Patient-centered communication and diagnostic testing. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:415–21. doi: 10.1370/afm.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epstein RM, Shields CG, Franks P, Meldrum SC, Feldman M, Kravitz RL. Exploring and validating patient concerns: relation to prescribing for depression. Annals of Family Medicine. 2007;5:21–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein RM. Mindful Practice in Action (I): Technical Competence, Evidence-Based Medicine and Relationship-Centered Care. Families Systems and Health. 2003;21:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamblyn R, Berkson L, Dauphinee WD, Gayton D, Grad R, Huang A, Isaac L, McLeod P, Snell L. Unnecessary prescribing of NSAIDs and the management of NSAID- related gastropathy in medical practice. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127:429–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-6-199709150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, Franz CE, Azari R, Wilkes MS, Hinton L, Franks P. Influence of patients' requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. J Amer Med Assoc. 2005;293:1995–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of Vignettes, Standardized Patients, and Chart Abstraction A Prospective Validation Study of 3 Methods for Measuring Quality. J Amer Med Assoc. 2000;283:1715–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown JB, Stewart MA, Ryan BL. Working Paper Series, Paper # 95-2. Second. Thames Valley Family Practice Research Unit and Centre for Studies in Family Medicine; London, Ontario, Canada: 2001. Assessing Communication Between Patients and Physicians: The Measure of Patient-Centered Communication (MPCC) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall JA, Irish JT, Roter DL, Ehrlich CM, Miller LH. Satisfaction, gender, and communication in medical visits. Medical Care. 1994:1216–31. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199412000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall JA, Roter DL, Milburn MA, Daltroy LH. Patients'Health as a Predictor of Physician and Patient Behavior in Medical Visits: A Synthesis of Four Studies. Medical Care. 1996;34:1205–18. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199612000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zachariae R, Pedersen CG, Jensen AB, Ehrnrooth E, Rossen PB, Von Der Maase H. Association of perceived physician communication style with patient satisfaction, distress, cancer-related self-efficacy, and perceived control over the disease. British Journal of Cancer. 2003;88:658–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong LML, Visser MRM, Lammes FB, De Haes J. Doctor-patient communication and cancer patients' quality of life and satisfaction. Patient Education and Counseling. 2000;41:145–56. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epstein RM. Mindful practice. J Amer Med Assoc. 1999;282:833–39. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein RM, Siegel DJ, Silberman J. Self-monitoring in clinical practice: a challenge for medical educators. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2008;28:5–13. doi: 10.1002/chp.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Arnold RM, Tattersall MH. Discussing life expectancy with terminally ill cancer patients and their carers: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:733–43. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson TM, Alexander SC, Hays M, Jeffreys AS, Olsen MK, Rodriguez KL, Pollak KI, Abernethy AP, Arnold R, Tulsky JA. Patient-oncologist communication in advanced cancer: predictors of patient perception of prognosis. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1057. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0372-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fallowfield L. Truth sometimes hurts but deceit hurts more. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;809:525–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliative Medicine. 2002;16:297–303. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm575oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leydon GM, Boulton M, Moynihan C, Jones A, Mossman J, Boudioni M, McPherson K. Cancer patients' information needs and information seeking behaviour: in depth interview study. British Medical Journal. 2000;320:909–13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7239.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eckles RE, Meslin EM, Gaffney M, Helft PR. Medical ethics education: Where are we? Where should we be going? A review. Academic Medicine. 2005;80:1143–52. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200512000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kramer P. Doctors discuss how to break bad news. ASCO Daily News. 2008;1:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedrichsen M, Milberg A. Concerns about Losing Control When Breaking Bad News to Terminally Ill Patients with Cancer: Physicians' Perspective. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9:673–82. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Fryer-Edwards KA, Alexander SC, Barley GE, Gooley TA, Tulsky JA. Efficacy of Communication Skills Training for Giving Bad News and Discussing Transitions to Palliative Care. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:453–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lienard A, Merckaert I, Libert Y, Delvaux N, Marchal S, Boniver J, Etienne AM, Klastersky J, Reynaert C, Scalliet P. Factors that influence cancer patients' anxiety following a medical consultation: impact of a communication skills training programme for physicians. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1450–58. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, Quill TE. Association of an Educational Program in Mindful Communication With Burnout, Empathy, and Attitudes Among Primary Care Physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284–1293. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]