Abstract

Some evidence suggests that motivational approaches are less efficacious—or even counter-productive—with persons who are relatively motivated at baseline. The present study was conducted to examine whether disordinal moderation by baseline motivation could partially explain negative findings in a previous study (Winhusen et al., 2008). Analyses also focused on the relative utility of the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment scale (URICA), vs. a single goal question as potential moderators of Motivation Enhancement Therapy (MET). Participants were 200 pregnant women presenting for substance abuse treatment at one of four sites. Women were randomly assigned to either a 3-session MET condition or treatment as usual (TAU). Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) revealed no significant moderation effects on drug use at post-treatment. At follow-up, contrary to expectations, participants who had not set a clear quit goal at baseline were less likely to be drug-free if randomized to MET (OR = .48); participants who did set a clear quit goal were more likely to be drug-free if randomized to MET (OR = 2.53). No moderating effects were identified via the URICA. Disordinal moderation of MET efficacy by baseline motivation may have contributed somewhat to the negative results of the Winhusen et al. (2008) study, but in the opposite direction expected. A simple question regarding intent to quit may be useful in identifying persons who may differentially respond to motivational interventions. However, moderation effects are unstable, may be best identified with alternate methodologies, and may operate differently among pregnant women.

Keywords: Pregnant, substance abuse, Motivational Enhancement Therapy, moderation effect, motivation

1.0 Introduction

Motivational Interviewing (MI) and related approaches have become standard practice in many substance-abuse, mental-health, and primary care settings, and are often used whenever smoking, problem alcohol use, medication non-adherence, or related behaviors are noted. However, such practices conflict with evidence that MI may be ineffective or even counter-productive when used with persons who are already relatively motivated to change.

As early as 1996, Heather et al. found no difference between MI and skills-based counseling among a full sample of 174 adult male inpatients with problem alcohol use, but did find significant effects favoring MI (42% vs. 18% reductions in drinking 6 months after discharge) when analyses were restricted to participants who were low in readiness to change (Heather et al., 1996). The multi-site Project MATCH study also found some evidence that, at the one-year follow up point and among outpatients, Motivation Enhancement Therapy (MET) was associated with better long-term effects than Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for persons low in motivation (Project Match Research Group, 1997).

More recent studies have reported similar findings, with the additional suggestion that moderation by baseline motivation may be disordinal, such that MI can be counterproductive (rather than simply ineffective) with persons high in motivation. For example, Rohsenow and colleagues randomly assigned cocaine-dependent adults to 2 sessions of either MI or meditation-relaxation therapy (Rohsenow et al., 2004). Compared to meditation-relaxation, MI resulted in better substance use outcomes for participants with low baseline motivation to change (e.g., 4.4 vs. 10.1 cocaine use days in the first 3 months of follow-up), but worse outcomes for those with higher baseline motivation (e.g., 13.5 vs. 5.2 cocaine use days in the same period). Similarly, Stotts et al. randomly assigned cocaine-dependent participants to either brief MI plus detoxification, or detoxification only (Stotts et al., 2001). Participants randomly assigned to the MI condition were more likely to complete the detoxification program if they were higher in motivation (59.3% vs. 34.4% completion), and less likely to do so if they were lower in motivation (40.9% vs. 72.7%).

Such an effect, if reliable, might have several implications. First, it could necessitate additional guidelines regarding applicability as MI and its related approaches are increasingly adopted into the community. Second, such an effect could necessitate re-evaluation of the magnitude of effects associated with MI; they could be greater with persons who are well-matched, and weaker with those who are not. Finally, such an effect might explain why treatment effects are weak or absent in some studies. Variations in baseline motivation among study cohorts could result in some samples having high proportions of relatively motivated participants, with consequent weak effects for MI in those studies.

One such study is the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Clinical Trials Network MET for pregnant substance users study, which was designed to evaluate the efficacy of a 3-session adaptation of MET, compared to treatment as usual (TAU), in increasing treatment utilization and decreasing substance use. Two hundred pregnant substance users entering outpatient substance abuse treatment at one of four community substance abuse treatment centers were randomly assigned to receive MET or TAU in addition to other treatment provided at the clinic. This randomized, parallel, two group trial included a one month active study phase with two follow-up assessments completed at 1 and 3 months, respectively, following the end of the active study phase.

Despite adequate fidelity to the MET model, tightly controlled procedures, and highly reliable measures, MET was not associated with improved outcomes (Winhusen et al., 2008). The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the extent to which baseline motivation moderated outcomes in the Winhusen et al. MET for pregnant substance users study. We predicted that baseline motivation would emerge as a disordinal moderator of substance abuse outcomes, such that MET participants high in baseline motivation would show worse results than those assigned to TAU, whereas MET participants low in baseline motivation would exhibit better outcomes as compared to TAU.

2.0 Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited from intakes to the pregnant women treatment programs of the four participating agencies (in North Carolina, New Mexico, Indiana, and Kentucky; see Winhusen et al., 2008, for details on agency characteristics and selection). All participants were given a thorough explanation of the study and signed an informed consent form that was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating sites. Eligible participants were at least 18 years of age and pregnant (as confirmed by a pregnancy test) and not planning to terminate the pregnancy. To be eligible, participants were required to be identified as needing substance abuse treatment via the treatment agency's usual screening procedure. As with most pregnant women programs, the agencies we worked with did not require a positive drug screen for treatment eligibility; rather, self-report of substance use or risk of relapse was sufficient to enroll pregnant women into treatment. Participants were excluded from the study if they required residential or inpatient treatment (other than detoxification), were more than 32 weeks pregnant, planned to relocate from the area within 4 months of signing the study consent form, had pending legal charges that might lead to incarceration (other than those requiring the participant to attend treatment), or were a significant suicidal/homicidal risk. Of the 204 candidates signing consent, only 4 failed screening: 2 for not being pregnant, 1 for having a legal charge that could lead to incarceration, and 1 for having both an unstable living situation and a condition requiring residential or inpatient treatment.

2.2 Measures

Motivation to change was measured in two ways. First, subscale scores on the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Questionnaire (URICA; DiClemente & Hughes, 1990) were scored following standard procedures. Then, following the procedure utilized by Stotts et al. (2001), participants with a Contemplation score greater than their Action score were considered to be low in motivation; those with an Action score higher than their Contemplation score were considered to be high in motivation, and ties were categorized as high motivation. The URICA as administered in this study retained its general language (e.g., “It might be worthwhile to work on my problem”), but utilized a more focused introduction (“For all the statements that refer to your ‘problem,’ answer in terms of problems related to your drug use”).

Motivation was also measured via a simple self-report question from the Thoughts about Abstinence assessment (Hall et al., 1991), administered at baseline, regarding the participant's current goal for drug/alcohol use. For this question, participants selected from forced-choice responses that ranged from quitting permanently, to controlled use, to no change goal. Any choice of abstinence (either permanent or temporary) was considered a clear quit goal. Prior research has suggested that baseline commitment to abstinence can be a predictor of drug use outcomes (Hall et al., 1991).

Drug use was defined as any evidence of use during the follow-up period, as indicated by either self-report or a positive urinalysis. Using this definition, 46.9% of participants were positive for drug use at the 3 month follow-up, yielding good ability to discriminate between participants in terms of use.

2.3 Procedures

Pregnant women identified by treatment program clinical staff as needing substance abuse treatment, and who expressed a willingness to learn more about the study, were referred to the research assistant (RA). After signing the Informed Consent Form, the study candidate completed screening and baseline assessments. Ineligible individuals continued into the site's standard intake assessment and treatment program. Eligible participants were assigned to MET or TAU via urn randomization to balance on 3 dichotomous variables: pressure to attend treatment, self-report of drug and alcohol use, and need for methadone maintenance.

The active study phase was 4 weeks in duration. During this time, participants in both treatment conditions were offered at least 3 individual sessions with a clinician. Participants in both conditions were encouraged to participate in the other treatment services offered by the program (e.g., group treatment, case management, etc.). During the first month of treatment, participants were scheduled to meet with the RA on a weekly basis. In addition, the participants were scheduled to meet with the RA at the 1 and 3 month follow-up visits. Study participants received $30 in retail scrip or vouchers for each of the 5 research visits that were relatively long (i.e., the 2 baseline visits, the end of active phase visit, and the 2 follow-up visits) and $25 for each of 3 research visits that were relatively brief.

2.4 Data analysis

Results were analyzed using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE), which can analyze data with non-normal outcomes while taking correlations between observations—as in repeated measures—into account. We entered interaction terms into the GEE equations to evaluate moderation (Baron and Kenny, 1986). We also examined estimated marginal means, odds ratios, and Logit d (an analogue of Cohen's d for dichotomous outcomes) to characterize the magnitude of observed differences between subgroups. Following procedures utilized in Winhusen et al. (2008), all analyses controlled for key baseline differences between the MET and TAU groups (i.e., proportion of participants with cocaine as the primary drug of abuse, proportion with marijuana as the primary drug of abuse, proportion with pressure to attend treatment, and minority status)1.

3.0 Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

Participant characteristics are described in detail elsewhere (Winhusen et al., 2008). The participants were, on average, 26 years of age and 20 weeks pregnant at the time of randomization. Most study participants were unmarried and unemployed and had, on average, a high school education. The sample was fairly diverse in terms of race and ethnicity, with approximately 40% Caucasians, 35% African Americans, and 21% Hispanics. Ten of the TAU (12.8%) and 13 of the MET (16.6%) participants were no longer pregnant at the 1 month follow-up; thirty-nine of the TAU (50%) and 43 of the MET (55.1%) were no longer pregnant at the 3 month follow-up. Neither difference was statistically significant (p = .44 for the 1 month follow-up, and .52 for the 3-month follow-up). Just over half of participants were classified as motivated at baseline (56% by the URICA and 61% by the goal question), also with no significant differences between conditions (Table 1). As also seen in Table 1, the two treatment groups were similar in terms of TAU/MET sessions attended (the modal number of pre-treatment sessions attended was 3; 54.5% of participants attended all 3 TAU/MET sessions) and in terms of attrition (80.5% of participants completed the 4-week follow-up, and 73.0% completed the 12-week follow-up).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at baseline and follow-up, by group (N = 200)

| Total (N = 200) |

TAU (n = 98) |

MET (n = 102) |

p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 26.2 (5.4) | 25.1 (4.8) | 27.3 (5.7) | < .01 |

| Years of education (SD) | 11.5 (1.7) | 11.2 (1.4) | 11.7 (1.9) | < .05 |

| Weeks gestation (SD) | 20.3 (7.8) | 19.9 (7.5) | 20.7 (8.2) | .46 |

| Met DSM-IV drug abuse criteria*(SD) | 7 (3.8%) | 2 (2.1%) | 5 (5.6%) | .21 |

| Met DSM-IV drug dependence criteria* (SD) | 66 (35.9%) | 33 (34.7%) | 33 (37.1%) | .89 |

| Expected success in quitting† (SD) | 7.6 (2.0) | 7.8 (1.7) | 7.3 (2.2) | .17 |

| Expected difficulty of quitting† (SD) | 5.4 (2.9) | 5.3 (3.0) | 5.5 (3.2) | .55 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | < .05 | |||

| White | 82 (41.2%) | 47 (48.5%) | 35 (34.3%) | |

| African-American | 71 (35.7%) | 32 (33.0 %) | 39 (38.2%) | |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 15 (7.5%) | 11 (11.3%) | 4 (3.9%) | |

| Hispanic | 43 (21.6%) | 17 (17.5%) | 26 (35.5%) | |

| Other | 6 (3.0%) | 2 (2.1%) | 4 (3.9%) | |

| Employed full or part time (%) | 49 (24.5%) | 27 (27.6%) | 22 (21.6%) | .32 |

| Attended all 3 MET/TAU sessions (%) | 109 (54.5%) | 58 (59.2%) | 51 (50.0%) | .19 |

| Completed 4-week follow-up | 161 (80.5%) | 82 (83.7%) | 79 (77.5%) | .27 |

| Completed 12-week follow-up | 146 (73.0%) | 71 (72.4%) | 75 (73.5%) | .86 |

| Motivated--URICA (%) | 111 (55.5%) | 51 (52%) | 60 (58.8%) | .34 |

| Motivated--goal question (%)† | 78 (60.9%) | 40 (63.5%) | 38 (58.5%) | .56 |

| Drug use at baseline (%) | 142 (71.4%) | 70 (71.4%) | 72 (71.3%) | .98 |

| Drug use at 1-month follow-up (%) | 69 (41.3%) | 36 (41.9%) | 33 (40.7%) | .88 |

| Drug use at 3-month follow-up (%) | 69 (46.9%) | 35 (48.6%) | 34 (45.3%) | .69 |

Note. Significance values for dichotomous data are based on Chi-square analyses; independent t-tests for age, education, and weeks gestation; and the Mann-Whitney U test for expected success/difficulty of quitting.

Data available for 184 participants (89 MET and 95 TAU)

Data available for 128 participants (65 MET and 63 TAU); 0 = lowest, 9 = highest

At the time of study enrollment, participants reported having used alcohol or drugs on an average of 9.6 days out the prior 28 days. Marijuana (31%) was most commonly reported as the primary substance of abuse, followed by cocaine (23.5%), opioids (13%), alcohol (10.5%), and methamphetamine (7.5%); the remaining 14.5% reported benzodiazepines or “other” as their primary drug of abuse. Just over one-third of participants met criteria for substance dependence (n = 66, or 35.9%) or abuse (n = 7, or 3.8%), with no significant difference between conditions.

3.2 Motivation as Measured by URICA (Motivation-U)

GEE analysis showed no significant group x time x Motivation-U interaction (Wald χ2[4] = 5.83, p = .212). Analysis of estimated marginal means, which represent the likelihood of being drug-free at follow-up, indicated no consistent differences in outcome with respect to Motivation-U, either as a moderator or as a predictor. Estimated marginal means, ORs, and Logit d (similar to Cohen's d for dichotomous outcomes) for the effects of Motivation-U on drug use outcomes were small (see Table 2). Supplemental analyses with other URICA formulas, such as that suggested by DiClemente et al. (1991), yielded similar results (data not shown).

Table 2.

Estimated marginal means, odds ratios, and Logit d of drug use outcomes comparing MET vs. TAU at low and high motivation

| URICA formula | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated marginal means | |||||

| MET | TAU | OR | Logit d | ||

| 1 month | |||||

| Low motivation | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.72 | -0.18 | |

| High motivation | 0.67 | 0.61 | 1.34 | 0.16 | |

| 3 months | |||||

| Low motivation | 0.53 | 0.50 | 1.15 | 0.08 | |

| High motivation | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.8 | -0.12 | |

| Self-report goal question | |||||

| Estimated marginal means | |||||

| MET | TAU | OR | Logit d | ||

| 1 month | |||||

| No quit goal | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.76 | -0.15 | |

| Quit goal | 0.54 | 0.47 | 1.34 | 0.16 | |

| 3 months | |||||

| No quit goal | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.48 | -0.40 | |

| Quit goal | 0.54 | 0.31 | 2.53 | 0.51 | |

Note. Estimated marginal means represent predicted likelihood of being drug-free; OR represents probability that a participant in the MET condition was drug free, as compared to the TAU condition; Logit d is an effect size analog of Cohen's d, for dichotomous outcomes.

3.3 Motivation as Measured by Goal Question (Motivation-GQ)

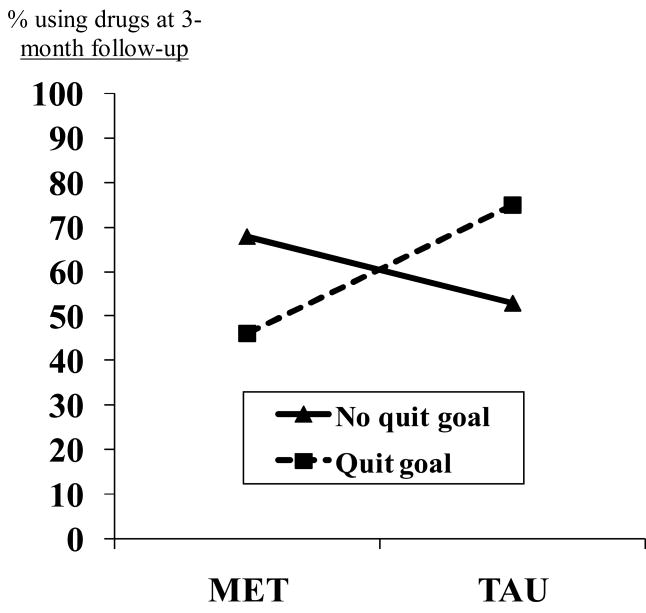

GEE analysis showed a non-significant group x time x Motivation-GQ interaction (Wald χ2[4] = 7.33, p = .12). Analysis of estimated marginal means revealed a trend toward effects in the opposite direction from that hypothesized at both follow-ups, particularly at the 3-month follow-up. Specifically, persons low in motivation (not setting a clear quit goal) showed worse results when randomized into MET (68% of MET participants vs. 53% of TAU participants using drugs at the 3-month follow-up), and persons high in motivation (those setting a clear quit goal) showed better results when randomized into MET (46% of MET participants vs. 75% of TAU participants using drugs at the 3-month follow-up; see Figure 1). Secondary GEE analysis of effects at the 3-month follow-up only, using Motivation-GQ, revealed a significant interaction effect (Wald χ2[1] = 4.66, p = .031). Estimated marginal means, ORs and Logit d for the effects of Motivation-GQ on drug use outcomes are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Percent of participants positive for drug use at 3-month follow-up, as a function of baseline quit goal (yes/no) and intervention group (MET vs. TAU)

3.4 Association between Motivation-U and Motivation-GQ

There was a small, positive association between Motivation-U and Motivation-GQ classifications (φ = .20, p = .007). Classification agreement between the two methods was 61%.

4.0 Discussion

Baseline motivation, whether measured via a formula involving the URICA or a single question regarding the participant's drug use goal, failed to explain significant variance in drug use outcomes in a repeated measures analysis. Further, the motivation variable yielded by the URICA formula (positive for motivation if the Action subscale score is ≥ the Contemplation subscale score) did not yield even a trend toward moderation, nor did supplemental analyses with other URICA formulas (i.e., DiClemente et al., 1991). However, secondary analyses revealed that a single question regarding drug use goal did serve as a disordinal moderator of drug use at the 3-month follow-up—but in the opposite direction from that predicted. Specifically, persons who endorsed a clear quit goal reduced their drug use more if they were assigned to the MET condition, and those who did not endorse a clear quit goal had better outcomes if assigned to the TAU condition. This finding is surprising given the results of prior studies (e.g., Rohsenow et al., 2004; Stotts et al., 2001), and is contrary to the hypothesis that motivational efforts with persons who are already willing to quit may be contraindicated.

There are a number of possible explanations for this unexpected finding. Perhaps most parsimoniously, the process of change may simply be quite different among pregnant women. Pregnancy is a time of natural declines in substance use (Office of Applied Studies, 2004). Motivational processes may thus be unique during this period. For example, relatively unmotivated pregnant women could be uniquely responsive to direct assistance with change, perhaps out of general receptiveness to interventions that are consistent with a shared goal (a healthy pregnancy). That is, concern from others for one's pregnancy may be more easily accepted and less likely to arouse resistance than concern for one's own general welfare—which may be neither wanted nor trusted. Similarly, relatively unmotivated pregnant women could be uniquely reactive to discussions of the consequences of their substance use, discussions that may be more likely to elicit counter-productive levels of guilt than would be the case in a non-pregnant person. Conversely, relatively motivated pregnant women may be uniquely responsive to motivational approaches, perhaps because the importance of the pregnancy is less easily discounted than more typically elicited pro-change factors such as one's health, values, or finances. Whereas reverting to considerations of “Why change?” may pull the majority of motivated persons back towards ambivalence, doing so with already motivated pregnant women may be more like dipping into a relatively inexhaustible source of commitment motivation.

Overall, however, the most consistent result in this study was one of no interaction between baseline motivation and group assignment. The reasons for this are unclear. As noted above, unique motivational features that are at work during pregnancy may reverse or attenuate interactions such as those noted by Rohsenow et al. (2004) and Stotts et al. (2001). Similarly, the clear declines in drug use in this sample (from 71.4% at baseline to 46.9% at the 3-month follow-up) raise a second possibility: although these impressive effects may be a result of treatment, they could also be a function of powerful internal and external forces unrelated to treatment. It may be difficult for any intervention approach to augment the forces already present. This suggestion is supported by mean ratings of expected success and difficulty of quitting, as measured prior to the initiation of treatment: participants, on average, rated themselves a 7.5 on a 0 – 9 scale (with 9 being highest) for expected success in quitting, and a 5.5 (on the same scale) for expected difficulty of quitting (see Table 1). Clearly, these women were relatively ready to change, and relatively confident in their ability to do so. Lacking a no-treatment control group, this dataset cannot address the extent to which—if at all—each treatment approach augmented the natural change that takes place during pregnancy.

Similar concerns could be raised with respect to the intensive assessment all participants received prior to and during the trial. There is growing evidence that intensive assessment can itself have significant motivational effects (e.g., Clifford et al., 2007; Epstein et al., 2005; Kypri et al., 2007). In the present study, the total baseline assessment was nearly 4 hours in length; the post-treatment assessment was one hour and 45 minutes long, and during-treatment assessments were 35 minutes each. If treatment-related effects are not strong enough to explain variance beyond that explained by assessment itself, then little in the way of moderation effects would be expected.

Further, the use of community therapists is a key feature of the NIDA Clinical Trials Network approach, which is intended to evaluate the ability to move efficacious approaches into community settings. However, interactions between baseline motivation and intervention approach may prove to be quite different in effectiveness studies, where factors such as fidelity, client characteristics, scope of treatment, and other factors can vary considerably from those in research/academic settings. Both Rohsenow et al. (2004) and Stotts et al. (2001) utilized therapists who were employed by the University; therapists in Project Match were a mix of university-based and community-based professionals.

Additionally, moderation effects are highly unstable and should be interpreted with caution. The studies previously showing disordinal moderation were not large, and many other studies of motivational approaches do not report results of interaction analyses involving baseline motivation. Notably, a recent analysis from the United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial (N = 740) found no support for any matching hypothesis, including one predicting an interaction between baseline motivation and Motivation Enhancement Therapy (UKATT Research Team, 2008). More definitive research using large, representative samples may be necessary in order to make conclusive statements regarding when such interactions are most likely to occur.

In addition to being pregnant, the participants in this sample differed from those in previous studies in a second important way: their rate of drug dependence was 35.9%, compared to the 100% rates of cocaine dependence in the Rohsenow et al. (2004) and Stotts et al. (2001) studies, and the near 100% rate of alcohol dependence in Project Match (e.g., Project Match Research Group, 1997). Interactions between motivation and treatment approach may be more marked in substance-dependent persons. For example, perhaps substance-dependent persons—when already motivated—are more easily set back by a failure to quickly begin the change process. Discussions of why one might wish to change at all could in fact help pull motivated dependent persons back into a more ambivalent state, whereas swift action could reinforce motivation. However, it is worth noting that drug use during pregnancy is itself more likely to be indicative of a drug use disorder than is mere use outside of pregnancy.

Relatedly, subtle differences in URICA versions may also have contributed to the observed differences in results. The Rohsenow et al. (2004) study utilized a cocaine-specific version of the URICA, whereas Stotts et al. (2001) appear to have utilized a more general “drug use” version. Similarly, as noted above, the version of the URICA utilized in the present study refers generally to “drug use.” Focused measures of motivation may be more sensitive to motivation X treatment type interactions, particularly when—as in the Rohsenow and Stotts studies—the sample is homogenous with respect to primary drug of abuse.

Finally, there is reason to question the current methodology in terms of identifying what are essentially person by situation matching effects (Lakey and Ondersma, 2008). Generalizability (Cronbach et al., 1972) or Social Relations Model (Kenny, 1994) approaches regularly identify strong person X situation matching effects, whereas between group designs (as used in the present study) do not (e.g., Project Match Research Group, 1997). Single individual difference variables, such as baseline motivation, are not able to predict patterns of responses to multiple situations/treatments, and so may form a poor basis on which to seek such effects. Data presented by Lakey and Ondersma (2008) indicate clearly that moderator/matching effects are not detectable using standard approaches, but are clearly and strongly present using a Generalizability/Social Relations Modeling design. Such analytical approaches, however, require each participant to be exposed to multiple unique treatment approaches/situations, and so could not be utilized for the present analysis.

Regardless of the mechanism behind the observed effects, it is interesting that the goal question—despite only modest overlap with the URICA-based categorization—seemed to have greater utility in identifying different patterns of response to motivational treatment. The Transtheoretical model on which the URICA is based has been the subject of criticism (Adams and White, 2005; West, 2005), as has the URICA itself (Carey et al., 1999). In contrast, the atheoretical goal question is simple, intuitive, and more easily used in community settings, and its success is not without precedent (Hall et al., 1991). Its direct targeting of willingness to commit to change also maps well onto research suggesting that commitment to a change goal is a key indicator during MI (Amrhein et al., 2003).

4.1 Limitations

A number of limitations should be considered in interpreting the present findings. First, the present analyses were secondary; the main study from which these data were derived was not designed with the present analyses in mind. One way that this impacts the present analysis is with respect to power. The original study was not powered to detect the kinds of interactions sought after in this analysis. (However, the magnitude of the interaction effects observed in the present study suggests that, even with sufficient power, their clinical significance is likely to be limited.) Second, as noted, these findings with pregnant women may not generalize to other samples. The relatively small sample size and primarily low-SES nature of the present sample compounds issues regarding generalizability. Third, drug use was relatively light in the present study; 71.4% endorsed some drug use at baseline, but only 39.7% met criteria for a drug use disorder. Results may have differed for a sample with greater severity of problems related to drug use. Finally, motivation is a complex construct that could be measured in many ways. The two methods used here represent only two of many possibilities, and neither has been subjected to thorough validation.

4.2 Conclusions

Disordinal moderation by baseline motivation does not explain significant overall variance in drug use outcomes in Winhusen et al. (2008). However, the drug use goal question was a significant moderator of the association between intervention condition and outcomes at the final (3-month) follow-up, in the opposite of the expected direction. These findings suggest substantial complexity in the situations for which motivational approaches are best-suited. Further research should clarify the persons and situations in which motivational approaches should be utilized. However, forecasting response in this way may be difficult given the many complex ways in which individuals and situations can vary. Experiential methods of identifying candidates for motivational interventions, in which a single patient is briefly exposed to two or more approaches, may be a more fruitful approach (Lakey & Ondersma, 2008).

Regardless, there is abundant evidence that (a) brief motivational interventions can be quite helpful for many individuals, but not all; (b) baseline motivation can at times moderate outcomes in trials of such approaches; and (c) the situations in which adequate motivation attenuates, facilitates, or has no association with the efficacy of motivational approaches remain unclear.

Footnotes

Age was not included as a covariate in order to maintain consistency with Winhusen et al. (2008). Adding age as a covariate did not change the results (data not shown).

References

- Adams J, White M. Why don't stage-based activity promotion interventions work? Health Educ Res. 2005;20:237–243. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, Fulcher L. Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:862–878. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Purnine DM, Maisto SA, Carey MP. Assessing readiness to change substance abuse: A critical review of instruments. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 1999;6:245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, Maisto SA, Davis CM. Alcohol treatment research assessment exposure subject reactivity effects: part I. Alcohol use and related consequences. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2007;68:519–528. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ, Gleser GC, Nanda H, Rajarathaj N. The Dependability of Behavioral Measurements: Theory of Generalizability for Scores and Profiles. Wiley; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS. The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EE, Drapkin ML, Yusko DA, Cook SM, McCrady BS, Jensen NK. Is alcohol assessment therapeutic? Pretreatment change in drinking among alcohol-dependent women. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:369–378. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman DA. Effects of commitment to abstinence, positive moods, stress, and coping on relapse to cocaine use. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:526–532. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Rollnick S, Bell A, Richmond R. Effects of brief counselling among male heavy drinkers identified on general hospital wards. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1996;15:29–38. doi: 10.1080/09595239600185641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Interpersonal perception: A social relations analysis. Guilford; New York: 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Langley JD, Saunders JB, Cashell-Smith ML. Assessment may conceal therapeutic benefit: findings from a randomized controlled trial for hazardous drinking. Addiction. 2007;102:62–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, Ondersma SJ. A new approach for detecting client-treatment matching in psychological therapy. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2008;27:56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies. Pregnancy and substance use. 2004 http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k3/pregnancy/pregnancy.htm accessed on.

- Project Match Research Group. Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Martin RA, Colby SM, Myers MG, Gulliver SB, Brown RA, Mueller TI, Gordon A, Abrams DB. Motivational enhancement and coping skills training for cocaine abusers: effects on substance use outcomes. Addiction. 2004;99:862–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotts AL, Schmitz JM, Rhoades HM, Grabowski J. Motivational interviewing with cocaine-dependent patients: a pilot study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:858–862. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UKATT Research Team. UK Alcohol Treatment Trial: client-treatment matching effects. Addiction. 2008;103:228–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R. Time for a change: putting the Transtheoretical (Stages of Change) Model to rest. Addiction. 2005;100:1036–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhusen T, Kropp F, Babcock D, Hague D, Erickson SJ, Renz C, Rau L, Lewis D, Leimberger J, Somoza E. Motivational enhancement therapy to improve treatment utilization and outcome in pregnant substance users. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]