Abstract

Job displacement is widely considered a negative life event associated with subsequent economic decline and depression as established by numerous prior studies. However, little is known about whether the form of job displacement (i.e. layoffs versus plant closings) differentially affects depression. We assess the effects of different ways in which a worker is displaced on subsequent depression among U.S. men and women nearing retirement. We hypothesize that layoffs should be associated with larger effects on depression than plant closings, particularly among men. Our findings generally support our hypotheses. We find that men have significant increases in depression as a result of layoffs, but not as a result of plant closings, while the reverse is true among women.

Keywords: job displacement, layoff, plant closing, depression, Health and Retirement Study

Recent periods of economic reorganization in the U.S. have been associated with increasingly widespread job insecurity and waves of job displacement (Farley 1996; Kalleberg 2000; Levy 1995; Wetzel 1995). Defined as involuntary job loss resulting from a layoff, downsizing, or plant closing, job displacement is associated with significant periods of non-employment and declines in subsequent earnings and job quality (Brand 2006; Fallick 1996; Farber 2005; Hammermesh 1989; Jacobson, LaLonde, and Sullivan 1993; Kletzer 1998; Podgursky and Swaim 1987; Ruhm 1991; Stevens 1997). An extensive body of research also links job displacement to increases in subsequent levels of depression (Burgard, Brand, and House 2007; Dooley, Fielding, and Levi 1996; Gallo et al. 2000; Gallo et al. 2006b; Kasl and Jones 2000; Kessler, Turner, and House 1988, 1989; Turner 1995; Warr and Jackson 1985).

Older workers' share of job displacements has grown disproportionately in recent years (Schmitt 2004); recent estimates indicate that about one in five older workers lose their jobs over a ten to twelve year period (Johnson, Mermin, and Uccello 2005). There is also evidence to suggest that the negative economic and psychological effects of job displacement have been increasing among older workers (Couch 1998; Chan and Stevens 2001; Gallo et al. 2000; Gallo et al. 2006b). Job disruptions among older workers may be particularly damaging, as late-career employment transitions are less common and older workers are more likely to have accumulated non-transferable firm- and/or industry-specific skills, wages, and benefits, leading to poor reemployment prospects and substantial economic hardship (Dooley and Catalano 1999; Farber 2005; Kessler, Turner, and House 1988, 1989; Price, Choi, and Vinokur 2002). Moreover, lost labor earnings can reduce wealth accumulated through pensions, Social Security, and other savings, thus threatening retirement security.

A few studies (Gibbons and Katz 1991; Hu and Tabor 2005; Stevens 1997) have explored differences in the economic effects of different forms of job displacement. These studies assess whether post-displacement unemployment duration and earnings penalties vary according to whether workers were displaced via layoff/downsizing, which affect only a portion of workers in a firm, or by plant closing, in which all workers lose their jobs. Less is known, however, about differences in the effects of different forms of job displacement on depression, particularly among older workers. In fact, just one study of which we are aware (Miller and Hoppe 1994) has explicitly studied the form of job loss in relation to depressive symptoms and this study was conducted with a homogenous sample without mental health information collected before the job loss. The objective of this research is therefore to assess whether the particular form of job displacement—layoff or plant closing—is associated with differences in its effect on depressive symptoms in a heterogeneous national U.S. sample with prospective mental health information.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, we present the literature on the effects of job displacement on associated outcomes, including a discussion of differential effects by mode of displacement as well as by gender. Second, we provide theoretical bases for expecting differences in the effects of displacement by form on subsequent depression and present our hypotheses. Third, we discuss our data, descriptive statistics, and estimation method. Fourth, we present the results of our analyses. Finally, we comment on our findings and discuss some implications of our research.

Research on the Effects of Job Displacement

Job displacement is a negative, often unpredictable life event that threatens economic, psychosocial, and somatic well-being (Brand and Burgard in press; Burgard, Brand, and House 2007; Jahoda 1982; Pearlin et al. 1981; Thoits 1995; Gallo et al. 2006a). Many studies have linked job displacement to downward socioeconomic mobility and psychological distress (Burgard, Brand, and House 2007; Dooley and Catalano 1999; Dooley, Catalano, and Wilson 1994; Dooley, Fielding, and Levi 1996; Gallo et al. 2000; Gallo et al. 2006b; Kessler, Turner, and House 1988, 1989; Leana and Feldman 1992; Pearlin et al. 1981; Turner 1995; Warr and Jackson 1985). Most estimates indicate that the average displaced worker experiences a substantial period of non-employment (Brand 2004; Fallick 1996; Farber 2005; Kletzer 1998; Podgursky and Swaim 1987; Ruhm 1991; Topel 1990); however, the length of non-employment has a high degree of variance (Seitchik 1991). Displaced workers also suffer substantial earnings losses, which are generally more persistent than non-employment effects. Earnings losses for displaced workers have been estimated to be between 10 and 25%, with wage scarring observed as long as ten years after the displacement event occurs (Brand 2004; Chan and Stevens 2001; Couch 1998; Fallick 1996; Farber 2005; Jacobson, LaLonde, and Sullivan 1993; Kletzer 1998; Podgursky and Swaim 1987; Ruhm 1991; Seitchik 1991; Topel 1990). As is true for non-employment effects, the degree to which displaced workers suffer earnings and wage losses is cyclical (Kletzer 1991; Topel 1990) and has a high degree of variance (Seitchik 1991).

Beyond economic losses, displaced workers may find that, when reemployed, their jobs are of lower quality in comparison to both the jobs they lost and the jobs held by their non-displaced counterparts (Brand 2006). Older workers may also face age discrimination when they search for a new job (McCann and Giles 2002). Some evidence suggests that many displaced workers in their late 50s and early 60s opt for early retirement rather than take on new jobs of lower quality (Farber 2005). However, workers forced into early retirement may be inadequately prepared to meet their retirement consumption needs (Bernheim 1997; Bernheim et al. 2000).

Job displacement typically entails a sequence of stressful experiences, from loss notification, anticipation, dismissal, and unemployment, to (in most cases) job search, re-training and eventual reemployment. Movement into unemployment is typically associated with assorted economic pressures, including reduced income, loss of health and pension benefits, and interruption of asset accrual. Loss of employment may also translate to restriction of socially-supportive collegial relationships (Brand and Burgard in press), new patterns of interaction with family members, and personal assessment in relation to individual values and societal pressures (Pearlin et al. 1981).

Both economic and affective consequences of displacement have been shown to vary by gender. Women generally experience longer spells of post-displacement unemployment than men (Podgursky and Swaim 1987), and married women, in particular, are less likely to return to work (Chan and Stevens 2001). In a study of a single plant closing, Broman et al. (1995) found that unemployment has a larger negative effect on depression for men than for women.

Different Effects by Forms of Job Displacement

Research suggests that the form of displacement produces differential economic consequences. The seminal work in this area (Gibbons and Katz 1991) demonstrated that layoffs are associated with higher economic losses than are plant closings. Gibbons and Katz (1991) argued that in the case of a layoff, discretionary dismissal of employees acts as a signal of below-average productivity, stigmatizing laid-off workers as “lemons.” The market's inference of this signal affects hiring and wage-setting decisions in the new firms, ultimately resulting in substantial non-employment and earnings losses. On the contrary, a plant closing, which typically arises from organizational restructuring and in which all workers are terminated without discretion, does not carry a comparable performance signal. Employment and earnings penalties for workers displaced in this manner are therefore, on average, less severe.

Stevens (1997) also finds larger wage losses for workers displaced by layoffs than for those displaced by plant closings. Her understanding of this result is, nonetheless, somewhat of a departure from Gibbons and Katz (1991). Stevens proposes that the relative difference between the two groups has more to do with pre-displacement conditions than with earnings after separation. In other words, Stevens argues that it is not that laid-off workers have relatively lower post-displacement wages, but rather that they have higher wages prior to separation than workers displaced by plant closings.

The literature on the non-economic consequences of the nature of job termination is sparse. In an examination of the effect of earnings shocks on marital durability, Charles and Stephens (2004) consider differences in the mode of displacement on subsequent risk of divorce, reporting increased likelihood of divorce following a layoff, but not plant closing. With reasoning similar to the Gibbons and Katz (1991) lemon explanation, the authors attribute the higher risk of marital dissolution to the spouse's negative inference about the worker's personal role in the layoff. They maintain that the discretionary nature of the termination conveys to the spouse certain qualities of the displaced worker—principally, traits related to temperament and discipline—which may suggest a lack of marital fitness. This information is used by the spouse in the decision to dissolve the marriage (Charles and Stephens 2004). Although not proposed by the authors, it could also be that laid off workers are more likely to experience depressive symptoms which, in turn, negatively affect marriage.

There is only a small set of studies on the psychological consequences of the nature of job termination. Kessler, Turner, and House (1988, 1989) compared workers who indicated that they contributed to their termination (potentially similar to laid-off workers) with that of unemployed workers who attributed the termination to external conditions (potentially similar to workers displaced in plant closings), and find no significant differences between the two groups' post-job loss psychological distress. Kessler, Turner, and House (1988, 1989) did not examine whether gender modifies displacement experiences. In contrast, Miller and Hoppe (1994), in perhaps the most comparable investigation to ours, report higher anxiety and depressive symptoms among workers who were fired than among those whose positions were eliminated. (They use the phrase “laid off” to describe this latter group.) Ascribing their findings to greater internal attribution on the part of fired workers, the authors suggest that interpretation of the reason for termination is a pivotal intervening influence in the association between dismissal mode and emotional ill health. There are nonetheless numerous limitations to this report that restrict its generalizability. The study population was homogeneous (married, working-class men), selected from a small geographic area (San Antonio, Texas), and observed only after job loss, so that pre-separation measures of psychological distress could not be controlled, reducing the authors' position to make causal inferences.

Theoretical Model and Hypotheses

We propose that of the two modes of job displacement considered in this study, layoffs will generally be associated with higher depressive symptoms than plant closings. We expect that this will be so for two principal reasons. First, there is a greater potential for a personal aspect to a layoff that is not common to plant closings. In the case of layoffs, the greater likelihood for discretionary dismissal of employees can act as a signal of below-average productivity, as suggested by Gibbons and Katz (1991), such that laid-off workers may attribute the job loss to their own shortcomings, leading to compromised self-esteem, anxiety, and depression (Leanna and Feldman 1992; Miller and Hoppe 1994). This scenario contrasts with that of plant closings, in which clearly external influences, such as the health of the macro-economy or management's decision to restructure or relocate business units, provokes separation. As such factors are indubitably beyond the control of individual employees, workers displaced via business closings seldom perceive themselves as responsible for the job loss, and therefore experience less psychological distress.

Second, we contend that layoffs are more likely to serve as a negative signal to society of a worker's incompetence, inferior ability, or poor character (Charles and Stephens 1997; Gibbons and Katz 1991; Hu and Tabor 1995; Weiss 1995). The stigma of the layoff may produce direct psychological distress, through strained relations with colleagues, friends, and/or family members (Charles and Stephens 1997; Miller and Hoppe 1994). A more indirect effect of the layoff signal is, however, also possible. If potential employers interpret the layoff as an indication of ineptitude, hiring will be discouraged. The resulting difficulty of laid-off workers to secure suitable employment in a reasonable period may strain financial resources and bring about increases in depression. Plant closings, on the other hand, do not involve a negative signal that raises transactions costs for displaced workers. Thus, workers displaced in plant closings may experience lower levels of psychological ill health.

Despite our general assertion that post-displacement depressive symptoms will be higher for laid-off workers than for those terminated in business closings, we believe that this pattern may not hold for all groups. Several prior studies, such as Gibbons and Katz (1991), study only men; we expect that the psychological impact of displacement type will vary by gender. We presume that divergence in the economic roles of men and women (Bianchi 1995; Bird and Rieker 1999), especially among the cohort of workers approaching retirement, as represented by the HRS sample, will mean that layoffs will be a more harmful form of displacement for men than for women. Our reasoning is that the layoff's implication of personal incompetence is more psychologically detrimental to men who, in this age cohort, are assumed to have a more durable commitment to work role, a stronger attachment to the labor force, and greater psychosocial needs for reemployment than women (Bianchi 1995; Zalokar 1986).

Our hypotheses thus encompass heterogeneity by gender in the effect of job displacement mode on depression. To restate: We hypothesize that workers who lose jobs as a result of layoffs will have higher post-displacement depression than workers dismissed via plant closings. However, we expect that the negative psychological impact of layoffs will be greater for men than for women, owing to variation in identity and labor force attachment between the sexes. We also reason that post-displacement reemployment and financial assets may serve to mitigate some of the negative effects of displacement on depression.

Data, Descriptive Statistics, and Method

Data

We use longitudinal data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative study of men and women age 50 or older, begun in 1992 and designed to investigate health and economic consequences of older individuals as they advance from work to retirement. Earlier research using data from the HRS has documented a significant association between job displacement and subsequent depression (Gallo et al. 2000; Gallo et al. 2006b). At baseline, HRS participants included 12,652 individuals from 7,702 households. Baseline surveys were conducted in 1992, via face-to-face interviews. Follow-up interviews, completed every two years, were completed by telephone or mail. Blacks, Hispanics, and Florida residents were oversampled.

We restrict our sample to HRS participants who, in 1992, were between ages 51 and 61, were working for pay, and had at least one follow-up response. We use data from the first five HRS waves (1992-2000), so that study sample members are under 70 years of age at the final wave analyzed (n = 4,692).1 The sample comprises individuals who are assumed to have sufficient attachment to the labor force, and are therefore at risk for declines in mental well-being following job displacement. After listwise deletion on all variables used in the analyses, we have a final analysis sample of 4,471 individuals and 12,081 person-spells.2

Variable Measurement and Descriptive Statistics

Our primary explanatory variable, job displacement form, is based on the question: “Why did you leave that employer? Did the business close, were you laid off or let go, did you leave to take care of family members, or what?” While our designated “layoff” category may include more individualized events or mass layoffs/downsizings, we contend that such separations signal qualitatively different events than entire business closings both to the individual, family, and community. We represent job displacement form by two binary indicators, one indicating the loss of a job due to a layoff and another indicating the loss of a job due to a business (plant) closing, retrospectively reported at a given follow-up wave. The referent category is the non-displaced. The data are organized as person-spells. Thus, the layoff and plant closing variables equal one if a respondent lost a job due to a layoff or plant closing between 1992 and 1994 (as indicated by the 1994 survey wave), between 1994 and 1996 (as indicated by the 1996 survey wave), between 1996 and 1998 (as indicated by the 1998 survey wave), or between 1998 and 2000 (as indicated by the 2000 survey wave). A total of 203 men (9.4%) and 189 women (8.3%) experienced one or more layoff events and 107 men (4.9%) and 130 women (5.7%) experienced one or more plant closing events over the period 1992-2000.

The study outcome is depression, based on eight items from the twenty-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D). The eight CES-D items, which refer to presence of the symptom in the last week, are: [respondent] felt depressed; felt everything s/he did was an effort; experienced restless sleep; could not get going; felt lonely; felt sad; enjoyed life; was happy. The outcome measure is an index that represents a count of the number of depressive symptoms (range: 0-8; higher values indicate worse mental health). It was created by first reverse coding responses to the positively-phrased statements (i.e., the final two items), next dichotomizing responses to all eight items (the symptom was experienced “much,” “most,” or “all” of the time versus “little” or “none” of the time), and finally summing the transformed (dichotomized) variables. Adjusted reliability coefficients for the eight-item depression measure were 0.81 in 1994, 0.78 in 1996, and 0.77 in 1998, and 0.76 in 2000. The outcome is measured following each possible spell of job displacement, i.e. in 1994, 1996, 1998, and 2000.

The risk of job displacement varies along a number of dimensions that, in turn, condition the extent to which displacement may influence subsequent depression. Tables 1 and 2 describe such observed variables by displacement status for men and women, respectively. All covariates indicate person-spell mean values for pre-treatment measures. Race and education are time-invariant variables. White-collar occupation is taken from the first wave of data collection.3 The remaining variables are time-varying; measures indicate pre-treatment values, corresponding to 1992, 1994, 1996, and 1998. Thus, all indicators of marriage, job conditions, and health are measured prior to the displacement event. For example, if a layoff occurred in 1993 (and was thus reported at the 1994 survey wave), we control for employer tenure in 1992.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics by Sex and Job Displacement: HRS Men.

| Variables | Displaced, Layoff | Displaced, Plant Closing | No Displacement (ref. cat.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Invariant Independent Variables | |||

| Non-White | 8.6% (0.28) |

10.0% (0.30) |

9.9% (0.30) |

| High School or More | 78.2% (0.41) |

83.4% (0.37) |

83.2% (0.37) |

| Some College or More | 46.3% (0.50) |

31.7% * (0.47) |

47.7% (0.50) |

| White-Collar Worker | 54.1% (0.50) |

55.9% (0.50) |

59.1% (0.49) |

|

Time-Varying Independent Variables (1992, 1994, 1996, 1998) |

|||

| Married/Partnered | 81.4% (0.39) |

82.9% (0.38) |

84.6% (0.36) |

| Employer Tenure | 8.11 *** (10.69) |

10.64 † (11.39) |

13.44 (12.50) |

| Fulltime Worker | 77.8% (0.42) |

80.0% (0.40) |

80.2% (0.40) |

| Physical Health, Exc/VG | 55.6% (0.50) |

60.2% (0.49) |

59.3% (0.49) |

| Number of Health Conditions | 1.031 (1.02) |

0.775 ** (0.78) |

1.007 (0.99) |

| Depression (Baseline) | 0.883 (1.61) |

0.895 (1.47) |

0.737 (1.35) |

| Mediating Variables | |||

| Non-Employment (1994, 1996, 1998, 2000) |

50.9% *** (0.50) |

38.1% *** (0.49) |

20.5% (0.40) |

| Wealth (1992, 1994, 1996, 1998) |

$113,731 (187861) |

$76,000 * (108012) |

$146,906 (305345) |

| Wealth Change (1994-92, 1996-94, 1998-96, 2000-98) |

$28,276 (165281) |

$34,687 (109088) |

$40,758 (320551) |

|

Dependent Variable (1994, 1996, 1998, 2000) |

|||

| Depression | 1.379 ** (1.95) |

1.310 (1.82) |

0.939 (1.53) |

| Number of Obs. | 236 | 116 | 5414 |

Notes: Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. Layoff and plant closing indicate a worker lost a job for the stated reason between 1992-1994, 1994-1996, 1996-1998, or 1998-2000. All time-varying independent variables and the mediating wealth variable indicate person-spell mean values of pre-treatment measures (i.e., 1992, 1994, 1996, and 1998). Mediating variable non-employment and the depression outcome indicate post-spell values (i.e., 1994, 1996, 1998, and 2000). All statistics are weighted.

p<.10

p <. 05

p < .01

p < .001 (t-tests of difference in means between job loss category and no loss)

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics by Sex and Job Displacement: HRS Women.

| Variables | Displaced, Layoff | Displaced, Plant Closing | No Displacement (ref. cat.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Invariant Independent Variables | |||

| Non-White | 13.7% (0.34) |

14.5% (0.35) |

14.0% (0.35) |

| High School or More | 85.4% (0.35) |

75.6% * (0.43) |

83.8% (0.37) |

| Some College or More | 38.3% (0.49) |

27.0% *** (0.44) |

42.0% (0.49) |

| White-Collar Worker | 89.4% (0.31) |

80.7% *** (0.39) |

89.8% (0.30) |

|

Time-Varying Independent Variables (1992, 1994, 1996, 1998) |

|||

| Married/Partnered | 63.7% (0.48) |

75.0% * (0.43) |

65.2% (0.48) |

| Employer Tenure | 5.34 *** (8.26) |

5.60 * (8.54) |

8.60 (10.09) |

| Fulltime Worker | 48.4% (0.48) |

59.3% (0.49) |

64.4% (0.48) |

| Physical Health, Exc/VG | 57.1% (0.50) |

51.2% † (0.50) |

61.3% (0.49) |

| Number of Health Conditions | 1.106 (1.19) |

1.085 (1.11) |

1.074 (1.04) |

| Depression (Baseline) | 1.162 (1.84) |

1.113 (1.71) |

0.925 (1.60) |

| Mediating Variables | |||

| Non-Employment (1994, 1996, 1998, 2000) |

56.8% *** (0.50) |

48.6% *** (0.50) |

23.4% (0.42) |

| Wealth (1992, 1994, 1996, 1998) |

$142,993 (300914) |

$83,600 * (116792) |

$150,635 (346210) |

| Wealth Change (1994-92, 1996-94, 1998-96, 2000-98) |

$108,469 ** (615046) |

$17,112 (94101) |

$22,001 (304167) |

|

Dependent Variable (1994, 1996, 1998, 2000) |

|||

| Depression | 1.450 * (2.05) |

1.664 * (2.19) |

1.186 (1.81) |

| Number of Obs. | 216 | 144 | 5955 |

Notes: Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. Layoff and plant closing indicate a worker lost a job for the stated reason between 1992-1994, 1994-1996, 1996-1998, or 1998-2000. All time-varying independent variables and the mediating wealth variable indicate person-spell mean values of pre-treatment measures (i.e., 1992, 1994, 1996, and 1998). Mediating variable non-employment and the depression outcome indicate post-spell values (i.e., 1994, 1996, 1998, and 2000). All statistics are weighted.

p<.10

p <. 05

p < .01

p < .001 (t-tests of difference in means between job loss category and no loss)

The measurement of most of the variables described in Tables 1 and 2 is straightforward. We include a dichotomous measure of self-reported health indicating excellent or very good health. Number of health conditions ranges from 0-7, and is based on respondents' reporting a physician having diagnosed the respondent with diabetes, cancer, lung disease, heart problems, stroke, high blood pressure, or arthritis. We examine two variables that potentially mediate the relationship between job displacement and depression: employment status and wealth. Employment status indicates whether respondents were non-employed at the end of each two-year spell, i.e. in 1994, 1996, 1998, or 2000. Retired workers are considered non-employed. We also consider respondents' wealth at the beginning of each two-year spell and the change in wealth from the beginning to the end of each spell. Our measure of wealth includes values of checking and savings accounts; certificates of deposit, bonds, and Treasury bills; individual retirement accounts; stocks and mutual funds; vehicles; business equity; equity in real estate other than respondents' primary assets; and other reported non-housing assets.

We conduct t-tests of mean differences on all variables reported in Tables 1 and 2 between each category of job displacement and the reference category of no job loss. We find that men and women displaced as a result of plant closings have, on average, significantly less education than non-displaced workers. Women displaced as a result of plant closings are less likely to be white-collar workers. Workers displaced as a result of layoffs and plant closings have lower average levels of employer tenure than non-displaced workers and are less likely to be working at follow-up. Percentage non-employed post-displacement is considerable among laid-off workers, substantiating the Gibbons and Katz (1991) theory. Men and women displaced as a result of plant closings have less wealth than non-displaced workers. All workers have, on average, accumulated more wealth across waves; however, wealth accumulation over time is generally less among displaced workers, although not significantly less. Women displaced as a result of layoffs, however, have accumulated more wealth across waves than non-displaced women, possibly suggesting some form of more complicated selection process.

With the exception of men displaced as a result of plant closings, displaced workers are more likely to be depressed at follow-up than non-displaced workers. Men displaced as a result of layoffs have lower pre-displacement depression and higher post-displacement depression than men displaced as a result of plant closings, while women displaced as a result of layoffs have higher pre-displacement depression and lower post-displacement depression than women displaced as a result of plant closings.

Statistical Approach and Empirical Strategy

We estimate a series of nested models to assess the effects of layoffs and plant closings on subsequent levels of depression. Given our theoretical hypotheses, all analyses are stratified by gender. It has been established that people in worse mental health are at greater risk for selection into unemployment (Dooley, Fielding, and Levi 1996); we thus include baseline depression in all of our models. The first model in each set includes indicators of mode of displacement and baseline depression. The second model specifications further control for socio-demographic factors that may influence both selection into job loss and subsequent depression: race, education, marital status, white-collar occupation, employer tenure, fulltime employment status, self-reported overall health, and number of health conditions. We next estimate models that examine potentially mediating variables: post-spell non-employment, wealth, and wealth change. The influence of reemployment has been widely studied in the literature on the relationship between job loss and depression, with most studies suggesting a protective effect of securing economically and psychologically satisfactory new positions (Dooley and Catalano 1999; Kessler, Turner, and House 1988, 1989; Gallo et al. 2000; Warr and Jackson 1985). The evaluation of reemployment's mediating impact is particularly important in this study, as we anticipate that variation in the effect of displacement mode on depression may operate through post-displacement employment trajectories. Moreover, the amount of wealth accumulated may serve as a buffer against the negative effects of job loss, particularly among older workers. We include pre-displacement wealth to examine the impact of differential resources that workers have at their disposal at roughly the time of the displacement event (i.e., prior to any post-displacement depletion of financial assets), and include wealth change to examine the impact of possible depletion of financial assets from pre- to post-displacement.

We construct up to four person-spell records per HRS respondent. We use Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE), an extension of generalized linear models for the analysis of longitudinal data (Liang and Zeger 1986), to assess changes in depression up to two years after job displacement. When data are collected on the same subjects across successive points in time, these repeated observations are correlated over time. If this within-subject correlation is not corrected, then the standard errors of the parameter estimates will not be valid and erroneous inference may result. GEE adjusts for this within-subject correlation, producing consistent estimates of regression parameters and of their variance.

Results

We report results for the effects of layoffs and plant closings on depression stratified by sex in Table 3.4 Model 1 for men and Model 2 for women estimate the effects of layoffs and plant closings on depression controlling only for baseline depression. This test of differences is performed to introduce basic patterns in the data and provide a benchmark against which to evaluate changes that occur as a result of controlling for observed factors influencing the observed association. We find an opposite pattern of results among men and women. Considering the sub-sample of male workers, we find that displaced men who are laid off have significantly higher depression scores than men who are not displaced (β = 0.310; p<.01). This is not the case for men who lose jobs as a result of plant closings. Among women, the reverse is true: we find that women who lose jobs as a result of plant closings have higher depression scores than women who are not displaced (β = 0.378; p<.05), whereas we do not find a similar effect for women who lose jobs as a result of layoffs. Pre-displacement depression has a large and highly significant effect on post-displacement depression that appears to be roughly equivalent for men and women. Women have generally higher levels of depression, as indicated by the model constant.

Table 3. Effects of Layoffs and Plant Closings on Depression, 1992-2000, Generalized Estimating Equations Models: By Sex.

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 3 | Model 2 | Model 4 | |

| Layoff | 0.310 ** (3.25) |

0.284 ** (2.79) |

0.097 (0.84) |

0.090 (0.77) |

| Plant Closing | 0.195 (1.41) |

0.206 (1.43) |

0.378 * (2.23) |

0.311 † (1.88) |

| Depression (Baseline) | 0.757 *** (40.51) |

0.570 *** (25.99) |

0.726 *** (42.84) |

0.537 *** (27.27) |

| Non-White | --- | -0.014 (0.31) |

--- | 0.168 ** (3.24) |

| High School or More | --- | -0.253 *** (4.94) |

--- | -0.268 *** (4.13) |

| Some College or More | --- | -0.112 ** (2.83) |

--- | -0.147 *** (3.78) |

| Married/Partnered | --- | -0.241 *** (4.43) |

--- | -0.066 (1.59) |

| White-Collar Occupation | --- | -0.035 (0.89) |

--- | -0.223 ** (3.03) |

| Employer Tenure | --- | -0.005 *** (3.64) |

--- | -0.008 ** (3.26) |

| Fulltime Worker | --- | 0.089 † (1.68) |

--- | 0.212 *** (3.97) |

| Physical Health | --- | -0.270 *** (6.43) |

--- | -0.252 *** (5.40) |

| Num. Health Conditions | --- | 0.082 *** (4.18) |

--- | 0.120 *** (5.56) |

| Spell | -0.040 † (1.83) |

-0.004 (0.19) |

-0.035 (1.40) |

0.013 (0.55) |

| Constant | 0.476 *** (10.55) |

1.099 *** (10.98) |

0.621 *** (11.93) |

1.131 *** (10.20) |

| Wald χ2 | 1660.57 | 1419.90 | 1866.90 | 1629.75 |

| Number of Observations | 5766 | 5766 | 6315 | 6315 |

| Number of Groups | 2188 | 2188 | 2283 | 2283 |

Notes: Numbers in parentheses are t-ratios. Layoff and plant closing indicate a worker lost a job for the stated reason between 1992-1994, 1994-1996, 1996-1998, or 1998-2000. Time-varying independent variables indicate pre-spell characteristics (1992, 1994, 1996, and 1998). The depression outcome indicates post-spell status (1994, 1996, 1998, and 2000).

p<.10

p <. 05

p < .01

p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

Model 3 for men and Model 4 for women control for pre-displacement covariates that may influence the observed associations reported in Models 1 and 2. We continue to find a significant effect of layoffs on depression for men, although the size of the coefficient is reduced by about ten percent (β = 0.284; p<.01); we note a marginally significant effect of a plant closing on depression for women (β = 0.311; p<.10), reduced in magnitude by about twenty percent. Other coefficients work in expected directions: education, marriage, employment status and tenure, and health are protective for men and, with the exception of marriage, also for women. Moreover, white race and white-collar employment are additionally protective for women.

In Table 4, we report the impact of variables that potentially mediate the association between job displacement and depression: employment status and wealth (scaled in $10,000's). Again, the purpose of adding employment status to our models is to examine the degree to which variation in the effect of displacement mode on depression is the result of differences in opportunities to secure reemployment across displacement type. Post-displacement non-employment reduces the effect of a layoff by about twenty-five percent among men; the effect of a plant closing on depression among women is also reduced by about ten percent.5 The purpose of adding wealth and wealth change to our models is to examine the degree to which variation in the effect of displacement form on depression is the result of differences in wealth accumulation across displacement type. We find that wealth has a significant effect on depression among men, but not among women. The inclusion of these variables has very little impact upon the displacement effects on depression; we see a reduction in the coefficient of layoff on depression for men by about three percent, and a reduction in the (marginally significant) coefficient of plant closing on depression for women by about one percent.

Table 4. Effects of Layoffs and Plant Closings on Depression, 1992-2000, Generalized Estimating Equations Models: By Sex.

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 5 | Model 7 | Model 6 | Model 8 | |

| Layoff | 0.213 * (2.09) |

0.207 * (2.04) |

0.041 (0.35) |

0.044 (0.37) |

| Plant Closing | 0.158 (1.11) |

0.147 (1.03) |

0.277 † (1.68) |

0.273 † (1.65) |

| Depression (Baseline) | 0.556 *** (25.14) |

0.547 *** (24.63) |

0.520 *** (26.24) |

0.515 *** (25.94) |

| Non-White | -0.008 (0.17) |

-0.017 (0.36) |

0.175 ** (3.34) |

0.170 ** (3.20) |

| High School or More | -0.249 *** (4.83) |

-0.243 *** (4.68) |

-0.272 *** (4.15) |

-0.273 *** (4.15) |

| Some College or More | -0.111 ** (2.79) |

-0.102 * (2.54) |

-0.154 *** (3.89) |

-0.146 *** (3.64) |

| Married/Partnered | -0.238 *** (4.33) |

-0.236 *** (4.27) |

-0.073 † (1.73) |

-0.064 (1.49) |

| White-Collar Occupation | -0.032 (0.81) |

-0.017 (0.42) |

-0.221 ** (2.96) |

-0.221 ** (2.95) |

| Employer Tenure | -0.006 *** (4.30) |

-0.006 *** (4.01) |

-0.008 ** (3.48) |

-0.008 ** (3.41) |

| Fulltime Worker | 0.207 *** (3.54) |

0.196 ** (3.33) |

0.260 *** (4.54) |

0.254 *** (4.39) |

| Physical Health | -0.264 *** (6.25) |

-0.260 *** (6.18) |

-0.247 *** (5.24) |

-0.244 *** (5.11) |

| Num. Health Conditions | 0.076 *** (3.87) |

0.075 *** (3.80) |

0.119 *** (5.44) |

0.119 *** (5.42) |

| Post-Spell Non-Employment | 0.245 *** (4.67) |

0.250 *** (4.76) |

0.150 ** (2.81) |

0.152 ** (2.85) |

| Pre-Spell Wealth | --- | -0.0021 *** (4.72) |

--- | -0.0009 (1.04) |

| Pre- to Post-Spell Wealth Change | --- | -0.0002 (0.47) |

--- | -0.0004 (0.72) |

| Spell | -0.008 (0.39) |

-0.001 (0.05) |

0.007 (0.27) |

0.009 (0.38) |

| Constant | 0.980 *** (9.60) |

0.987 *** (9.67) |

1.105 *** (9.89) |

1.110 *** (9.92) |

| Wald χ2 | 1422.17 | 1414.62 | 1557.02 | 1535.49 |

| Number of Observations | 5766 | 5766 | 6315 | 6315 |

| Number of Groups | 2188 | 2188 | 2283 | 2283 |

Notes: Numbers in parentheses are t-ratios. Layoff and plant closing indicate a worker lost a job between 1992-94, 1994-96, 1996-98, or 1998-2000. All other independent variables as well as the mediating wealth variable indicate pre-spell characteristics (1992, 1994, 1996, and 1998). Mediating variable post-spell non-employment and the depression outcome indicate post-spell status (1994, 1996, 1998, and 2000).

p<.10

p <. 05

p < .01

p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

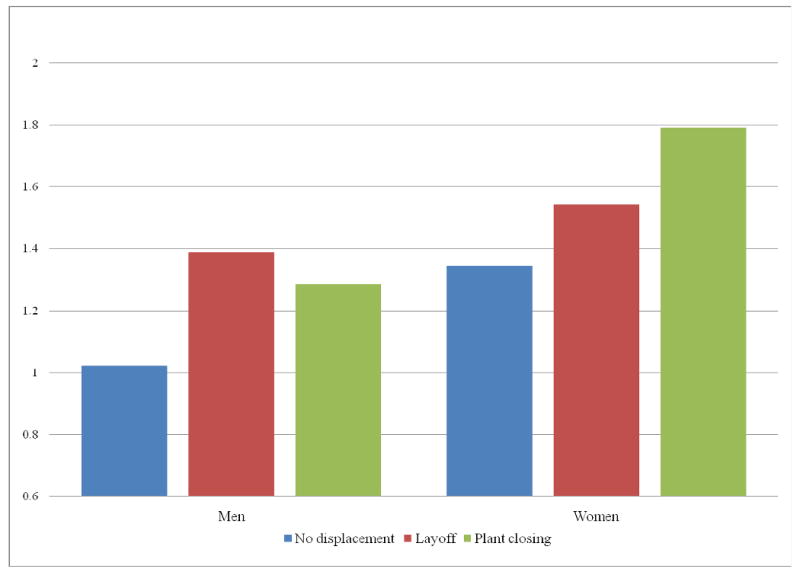

We display mean predicted values by sex in Figure 1, based upon Model 7 for men and Model 8 for women. Here we see clearly that women have higher levels of depression in each category (no displacement, layoff, and plant closing). For both men and women, workers who do not experience displacement have lower levels of depression than observationally equivalent workers who are displaced. However, whereas there are higher levels of depression among men who are displaced as a result of layoffs than among men who are displaced as a result of plant closings, there are higher levels of depression among women who are displaced as a result of plant closings than among women who are displaced as a result of layoffs.

Figure 1. Mean Predicted Values Based on Full Set of Pre-Disnlacement and Mediating Covariates: By Sex.

Discussion

In recent decades, the proportion of U.S. job displacements corresponding to older workers has grown, a trend which has encouraged interest in exploring the health effects of unemployment among individuals nearing retirement. Several prior studies have investigated depressive symptoms in relation to late-career job loss; findings from these studies suggest that late-career job loss is an influential negative life event accompanied by substantial emotional stress and consequent reductions in affective health. Still, the earlier research did not establish whether the form of displacement—plant closing or layoff—differentially determines the previously reported outcomes. The answer to this question is relevant to accurately directing intervention resources after job loss.

This study examined differences in the effect of job displacement on depressive symptoms by displacement form. We hypothesized that layoffs would be associated with larger effects on depression than plant closings. The foundation of our argument is that the greater discretionary character of a layoff may provoke self-attribution of the dismissal and instigate a negative market and community signal that could impede reemployment, both of which could conceivably bring about depression. We also theorized that gender differences in work role and labor force attachment would translate to intensified effects of layoffs for men.

As hypothesized, we found that men have a significant increase in depression resulting from layoffs. This result is consistent with the conclusions of Miller and Hoppe (1994), who reported higher depression among men who were selected for termination than among those whose jobs were eliminated. Among women, however, we observed a significant increase in depression associated with plant closings, but not for layoffs, a rather unanticipated finding. Furthermore, post-displacement employment status and financial resources explain roughly one-quarter of the effect of layoffs on depression among men, while explaining only about one-tenth of the effect of plant closings on depression among women. While we have hypothesized that differences in social roles may help to explain varying effects for men and women, future research should continue to explore the potential mechanisms by which these gender differences emerge.

There are several noteworthy advantages of this study. First, we use a national sample to analyze differences in displacement mode among older workers. Previous research on this topic was limited primarily to small geographic areas and/or demographically narrow samples. Second, the longitudinal structure of our study enabled us to control for pre-displacement measures of depression, strengthening our ability to infer that the observed effects are causal. And third, the large sample and relatively long follow-up provided an adequate number of observations to analyze males and females separately. The relevance of this gender-stratified analysis is reflected in our results, which suggest important differences in the effect of displacement mode by sex that would not be apparent with a more restricted sample.

A number of limitations also deserve mention. Our sample in this study was restricted to older workers. This means that, despite the importance of this group as a vulnerable population, we cannot draw inferences on the mental health effects of displacement mode for workers whose ages fall outside of the range considered. In addition, although the analytic sample is sizeable, it is not sufficiently large to analyze separately by race, i.e. the gender/race subsamples do not contain enough displacement events to perform inferential statistical testing. Also, mode of displacement is possibly measured with error. Still, this issue arises in any study attempting to disaggregate the mode of displacement from national survey data; data sources, such as administrative data that may contain more reliable measures of displacement mode suffer from other limitations, such as generalizability. Finally, our measure of reemployment, a potentially critical factor in the displacement-depression relationship, is somewhat crude. Although it is implicitly defined by job search effort, unemployment duration, and other aspects relevant to finding a new position, it is probably not fully capturing the impacts of these individual items.

This investigation augments the existing research on job displacement by providing evidence for considering the mode of displacement in future studies that examine mental health effects. Its findings demonstrate that the mode of job displacement translates to differences in changes in depressive symptomatology, and that these differences vary by gender. Recognizing these patterns will aid in designing and directing appropriate policies and services to address the psychological needs of displaced older workers.

Acknowledgments

William T. Gallo was supported by grants from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale (P30AG21342) and the National Institute on Aging (R01AG027045/K01AG021983). Becca R. Levy was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG05727) and the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation. The ideas expressed herein are those of the authors.

Biographies

Biographical Notes

Jennie E. Brand

Jennie E. Brand is Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of California – Los Angeles and a faculty affiliate at the California Center for Population Research. Her research focuses on the effects of social background, educational attainment, and labor market process and job conditions on socioeconomic attainment and well-being over the life course. She also studies the application and innovation of quantitative methods for analysis of panel data. Current research projects include evaluation of heterogeneity in the effects of early schooling, programs to assist disadvantaged students, and college completion on socioeconomic outcomes and the effects of employment insecurity, job loss, and job conditions on health and well-being.

Becca R. Levy

Becca R. Levy is an Associate Professor of Epidemiology and Psychology at the Yale School of Public Health. Her research explores psychosocial influences on aging. Ongoing projects examine the influence of ageism and age stereotypes on older adults, psychosocial determinants of longevity, and interventions to improve aging health. She received a Brookdale National Fellowship, the Margret M. Baltes Early Career Award in Behavioral and Social Gerontology, the Springer Award for Early Career Achievement on Adult Development and Aging, and the Donaghue Investigator Award.

William T. Gallo

William T. Gallo is a Research Scientist in the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health at the Yale University School of Medicine and a faculty affiliate at the Yale Program on Aging. An economist who was also trained in both social gerontology and epidemiology, his primary research interest is the health effects of involuntary job loss among U.S. workers nearing retirement. Dr. Gallo has published widely in this area, with two recent publications at the Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences and Occupational and Environmental Medicine.

Footnotes

Response rates in the first five waves of the HRS are generally quite good: 87.1 percent in wave 1, 89.1 percent in wave 2, 86.3 percent in wave 3, 84.9 percent in wave 4, and 84.0 percent in wave 5.

Most cases were lost due to missing data on depression. The final analysis sample is quite comparable to the full sample with only insignificant variations in observable characteristics; e.g., the analysis sample is 1-2 percentage points more likely to have completed high school and college and 1-2 percentage points more likely to be white-collar workers.

We chose not to allow this variable to vary across waves as there appeared to be little variability across waves, and the variable had a large amount of missing data in subsequent waves.

Gallo has tried various weights in previous HRS studies, including an analysis weight, simple household clustering, a combination of the two, and analysis weights adjusted for attrition. Overwhelmingly, the evidence suggests that they do little or nothing to the standard errors. Therefore, we do not include weights in any of our models. However, we do control for race.

We did not find significant interactions between layoff or plant closing and non-employment status on depression for men or for women, and therefore did not include these terms in our models.

Contributor Information

Jennie E. Brand, Email: brand@soc.ucla.edu, University of California – Los Angeles.

Becca R. Levy, Email: Becca.Levy@yale.edu, Yale University.

William T. Gallo, Email: william.gallo@yale.edu, Yale University.

References

- Bernheim B Douglas. The Adequacy of Personal Retirement Saving: Issues and Options. In: Wise DA, editor. Facing the Age Wave. Palo Alto: Hoover Institution Press; 1997. pp. 30–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim BD, Forni L, Gokhale J, Kotlikoff LJ. How Much Should Americans Be Saving for Retirement? American Economic Review. 2000;90:288–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi Suzanne. Changing Economic Roles of Women and Men. In: Farley R, editor. State of the Union: America in the 1990s; Volume One: Economic Trends. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1995. pp. 107–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bird Chloe E, Reiker Patricia P. Gender Matters: An Integrated Model for Understanding Men's and Women's Health. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;48:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand Jennie E. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Wisconsin – Madison, Department of Sociology; 2004. Enduring Effects of Job Displacement on Career Outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- Brand Jennie E. The Effects of Job Displacement on Job Quality: Findings from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2006;24:275–298. [Google Scholar]

- Brand Jennie E, Burgard Sarah A. Effects of Job Displacement on Social Participation: Findings over the Life Course of a Cohort of Joiners. Social Forces. 2008 doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0083. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman Clifford, Hamilton V Lee, Hoffman William, Mavaddat Roya. Race, Gender, and the Response to Stress: Autoworkers' Vulnerability to Long-Term Unemployment. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:813–842. doi: 10.1007/BF02507017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard Sarah A, Brand Jennie E, House James. Toward a Better Estimation of the Effect of Job Loss on Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:369–384. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Sewin, Stevens Ann Huff. Job Loss and Employment Patterns of Older Workers. Journal of Labor Economics. 2001;19:484–521. [Google Scholar]

- Charles Kerwin Kofi, Stephens Melvin., Jr Job Displacement, Disability, and Divorce. Journal of Labor Economics. 2004;22:489–522. [Google Scholar]

- Couch KA. Late Life Job Displacement. The Gerontologist. 1998;38:7–17. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley David, Catalano Ralph. Unemployment, Disguised Unemployment, and Health: The U.S. Case. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 1999;72:s16–s19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley David, Catalano Ralph, Wilson G. Depression from Unemployment: Panel Findings from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1994;22:745–65. doi: 10.1007/BF02521557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley David, Fielding Jonathon, Levi Lennart. Health and Unemployment. Annual Review of Public Health. 1996;17:449–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.002313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallick Bruce. A Review of the Recent Empirical Literature on Displaced Workers. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 1996;50:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Farber Henry S. Working Paper #498. Princeton University, Industrial Relations Section; 2005. What do we know about Job Loss in the United States? Evidence from the Displaced Worker Survey, 1984-2004. [Google Scholar]

- Farley Reynolds. The New American Reality: Who We Are, How We Got Here, Where We Are Going. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo William T, Bradley Elizabeth H, Siegel Michele, Stanislav Kasl. Health Effects of Involuntary Job Loss among Older Workers: Findings from the Health and Retirement Survey. Journals of Gerontology Series B – Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2000;55:S131–S140. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.3.s131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo William T, Hsun-Mei Teng, Falba Tracy A, Kasl Stanislav V, Krumholz Harlan M, Bradley Elizabeth H. The Impact of Late-Career Job Loss on Myocardial Infarction and Stroke: A 10-Year Follow-Up using the Health and Retirement Survey. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2006a;63:683–687. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.026823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo William T, Bradley Elizabeth, Teng Hsun-Mei, Kasl Stanislav V. The Effect of Recurrent Involuntary Job Loss on the Depressive Symptoms of Older Workers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2006b;80:109–116. doi: 10.1007/s00420-006-0108-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons Robert, Lawrence Katz. Layoffs and Lemons. Journal of Labor Economics. 1991;9:351–380. [Google Scholar]

- Hammermesh Daniel S. What Do We Know About Worker Displacement in the United States? Industrial Relations. 1989;28:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Luojia, Tabor Christopher. Institute for the Study of Labor, Discussion Paper No 1702. Bonn, Germany: 2005. layoffs, Lemons, Race, and Gender. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson Louis S, Lalonde Robert J, Sullivan Daniel G. Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers. American Economic Review. 1993;83:685–709. [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda M. Employment and Unemployment: A Social Psychological Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Richard, Gordon BT Mermin, Uccello Cori E. When the Nest Egg Cracks: Financial Consequences of Health Problems, Marital Status Changes, and Job Layoffs at Older Ages. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College; 2005. CRR WP 2005-18. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne L. Changing Contexts of Careers: Trends in Labor Market Structures and Some Implications for Labor Force Outcomes. In: Kerkhoff AC, editor. Generating Social Stratification: Toward a New Research Agenda. Boulder: Westview Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kasl SV, Jones BA. The Impact of Job Loss and Retirement on Health. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C, Turner J Blake, House James S. Effects of Unemployment on Health in a Community Survey: Main, Modifying, and Mediating Effects. Journal of Social Issues. 1988;44:69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C, Turner J Blake, House James S. Unemployment, Reemployment, and Emotional Functioning in a Community Sample. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:648–657. [Google Scholar]

- Kletzer Lori. Job Displacement. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1998;12:115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Leana C, Feldman D. Coping with Job Loss: How Individuals, Organizations, and Communities Respond to Layoffs. New York: Lexington: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Levy Frank. Incomes and Income Inequality. In: Farley R, editor. State of the Union: America in the 1990s. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Liang Kung-Yee, Zeger Scott L. Longitudinal Data Analysis Using Generalized Linear Models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- McCann R, Giles H. Ageism in the Workplace: A communications Perspective. In: Nelson T, editor. Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older workers. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Michael V, Hoppe Sue Keir. Attributions for Job Termination and Psychological Distress. Human Relations. 1994;47:307–328. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard, Lieberman Morton, Menaghan Elizabeth, Mullan Joseph. The Stress Process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podgursky Michael, Swaim Paul. Job Displacement and Earnings Loss: Evidence from the Displaced Worker Survey. Industrial and Labor relations Review. 1987;41:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Price Richard, Choi JN, Vinokur AD. Links in the Chain of Adversity Following Job Loss: How Financial Strain and Loss of Personal Control Lead to Depression, Impaired Functioning, and Poor Health. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2002;7:302–312. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.7.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm Christopher J. Are Workers Permanently Scarred by Job Displacement? The American Economic Review. 1991;81:319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt John. The Rise in Job Displacement, 1991-2004. Challenge. 2004;47:46–68. [Google Scholar]

- Seitchik Adam. Who Are Displaced Workers? In: Addison JT, editor. Job Displacement: Consequences and Implications for Policy. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens Ann Huff. Persistent Effects of Job Displacement: The Importance of Multiple Job Losses. Journal of Labor Economics. 1997;15:165–188. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits Peggy A. Stress, Coping, and Social Support Processes: Where Are We? What Next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topel Robert. Specific Capital and Unemployment: Measuring the Costs and Consequences of Job Loss. Carnegie Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy. 1990;33:181–224. [Google Scholar]

- Turner J Blake. Economic Conditions and the Health Effects of Unemployment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:213–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr Peter, Jackson Paul. Factors Influencing the Psychological Impact of Prolonged Unemployment and Reemployment. Psychological Medicine. 1985;15:795–807. doi: 10.1017/s003329170000502x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Andrew. Human Capital vs. Signaling Explanation of Wages. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1995;9:133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel James R. Labor Force, Unemployment and Earnings. In: Farley R, editor. State of the Union: America in the 1990s. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zalokar Nadja. Generational Differences in Female Occupational Attainment—Have the 1970's Changed Women's Opportunities? The American Economic Review. 1986;76(No 2):378–381. [Google Scholar]