Abstract

Rationale

Hypertension is a complex trait with deranged autonomic control of the circulation. Chromogranin B (CHGB) is the most abundant core protein in human catecholamine secretory vesicles, playing an important role in their biogenesis. Does common inter-individual variation at the CHGB locus contribute to phenotypic variation in CHGB and catecholamine secretion, autonomic stability of the circulation, or blood pressure in the population?

Methods and Results

To probe inter-individual variability in CHGB, we systematically studied polymorphism across the locus by re-sequencing CHGB (~6 kbp footprint spanning the promoter, 5 exons, exon/intron borders, UTRs) in n=160 subjects (2n=320 chromosomes) of diverse biogeographic ancestries. We identified 53 SNPs, of which 22 were common. We then studied n=1182 subjects drawn from the most extreme BP values in the population (highest and lowest 5th %iles), typing 4 common polymorphisms spanning the ~14 kbp locus. Sliding-window haplotype analysis indicated BP associations peaking in the 5′/promoter region, and most prominent in men, and a peak effect in the proximal promoter at variant A-261T (A>T), accounting for ~8/~6 mmHg SBP/DBP in males. The promoter allele (A-261) that was a predictor of higher DBP and SBP was also associated with lower circulating/plasma CHGB concentration (CHGB439-451 epitope) in twin pairs. In twins, the same CHGB variants that were predictors of lower basal CHGB secretion were also associated with exaggerated catecholamine secretion and BP response to environmental (cold) stress; likewise, women displayed increased plasma CHGB439–451, but decreased catecholamine secretion as well as BP response to environmental stress. The effect of A-261T on CHGB expression was confirmed in chromaffin cells by site-directed mutagenesis on transfected CHGB promoter/luciferase reporter activity, and the allelic effects of A-261T on gene expression were directionally coordinate in cella and in vivo. To confirm these clinical associations experimentally, we undertook targeted homozygous (−/−) ablation of the mouse Chgb gene; knockout mice displayed substantially increased BP, by ~20/~18 mmHg SBP/DBP, confirming the mechanistic basis of our findings in humans.

Conclusions

We conclude that common genetic variation at the CHGB locus, especially in the proximal promoter, influences CHGB expression, and later catecholamine secretion and the early heritable responses to environmental stress, eventuating in changes in resting/basal BP in the population. Both the early (gene expression) and late (population BP) consequences of CHGB variation are sex-dependent. The results point to new molecular strategies for probing autonomic control of the circulation, and ultimately the susceptibility to and pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease states such as hypertension.

Keywords: Genetics, hypertension, gene expression, catecholamine

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is a complex trait in which deranged autonomic control of the circulation may be an early etiological culprit. The sympathoadrenal system exerts minute-to-minute control over cardiac output and vascular tone. Genes governing catecholaminergic processes may play a role in the development of hypertension1. The chromogranins/secretogranins comprise a family of acidic, soluble proteins that are widely stored in secretory granules with hormones, transmitters, and neuropeptides throughout the endocrine and nervous systems 2. Chromogranin B (CHGB), first described in the 1980s, 3, 4 seems to be the quantitatively most abundant matrix protein in the core of human catecholamine storage vesicles 5, 6. Over- and under-expression studies in chromaffin cells indicate that CHGB plays an important role in secretory vesicle biogenesis 7.

CHGB has both extracellular and intracellular roles in the neuroendocrine system. Extracellular roles for CHGB are dependent on its extensive proteolytic processing within chromaffin granules at dibasic cleavage sites 8 to form smaller peptides; such peptides may have a role in the neuroendocrine/sympathoadrenal stress response to systemic infection 2. Within chromaffin cells and sympathetic axons, CHGB functions in sorting and trafficking of peptide hormone and neuropeptide precursors to secretory granules 9, perhaps as triggers to secretory granulogenesis 7.

Since excess sympathetic activity is implicated in causing hypertension 10, and alterations in sympathetic responses may occur even in the normotensive relatives of patients at genetic risk for later development hypertension, we wondered whether the sympathochromaffin mechanisms, such as the catecholaminergic CHGB system, might be altered in hypertension or in individuals at risk for development of hypertension. In this study, we undertook a systematic study of polymorphism at the human locus, by re-sequencing CHGB, discovering and associating a series of naturally occurring CHGB variants with gene expression in vivo, as well a series of sympathochromaffin traits eventuating in the disease state of essential hypertension.

METHODS

Subjects and clinical characterization

Subjects were volunteers from urban southern California (San Diego), and each subject gave informed, written consent; the protocol was approved by the institutional review board. Recruitment procures, definitions and confirmation of subject diagnoses are according to previous reports 11. Genomic DNA of each individual was prepared from leukocytes in EDTA-anticoagulated blood, using PureGene extraction columns (Gentra Biosystems, Minnesota).

Polymorphism discovery

Since allele frequencies and haplotypes may differ substantially across biogeographic ancestries, a series of n=160 individuals (i.e., 2n=320 chromosomes, supplementary Table 1) was selected to span a diverse range of 4 biogeographic ancestry groups: white (European ancestry), black (sub-Saharan African), east Asian, and Hispanic (Mexican American) ethnicities, for systematic/comprehensive discovery by re-sequencing. Characterization of 2n=320 chromosomes afforded us the >99% power for discovery of polymorphisms with as low as ~1.4% minor allele frequency. Ethnicity was established by self-identification. None of the subjects had a history of secondary hypertension, renal failure or diabetes mellitus.

Primary care population with extremes of high and low blood pressure

From a database of over 53,000 people (27,478 females and 25,528 males) in southern California, we ascertained 1182 European-ancestry individuals, of both sexes, from the highest and lowest 5th percentiles of a primary care population12 in DBP distribution. This population sample afforded us >90% power to detect genotype association with a trait when the genotype contributes as little as 3% to the total variation in males; the power is even higher in the females13. Evaluation included physical examination, blood chemistries, hemogram, and extensive medical history questionnaire. 1.98% of subjects were excluded because of elevated serum creatinine (>1.5 mg/dl).

Twin pairs

Twins enable estimation of heritability for any trait. In studies of CHGB heritability, as well as the influence of CHGB polymorphism on CHGB expression in vivo and the cold stress test in vivo, 171 twin pairs (342 individuals) were evaluated. Zygosity (69% monozygotic and 31% dizygotic pairs) was confirmed by extensive microsatellite and SNP genotyping, as described 14. Twins ranged in age from 15–84 years; 10% were hypertensive. All of the twins in these allelic/haplotype association studies were self-identified as of European (white) ancestry, to guard against the potentially artifactual effects of population stratification.

Molecular genetics

Resequencing of CHGB locus. (on-line supplement).

Genotyping of CHGB variants. (on-line supplement).

Phenotyping

Biochemical phenotyping. (on-line supplement).

Physiological phenotyping: Environmental (cold) stress test in twin pairs. (on-line supplement).

Statistical analyses

Estimates are stated as mean value ± one standard error. Heritability (h2) is the fraction of phenotypic variance accounted for by genetic variance (h2=VG/VP). Estimates of h2 were obtained by using the variance component method implemented in the Sequential Oligogenic Linkage Analysis Routines (SOLAR) package<www.sfbr.org/solar/> 15.

Haplotypes were inferred from common single nucleotide polymorphisms (minor allele frequency ≥10%) of CHGB by using either the HAP program 16, which can also generate a likely phylogeny for each variant, or by PHASE 17. Pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) between common SNPs was quantified as D′ by the GOLD (Graphical Observation of Linkage Disequilibrium) software package 18. Two-way ANOVA or multivariate general linear modeling, using post-hoc Bonferroni corrections, was performed in SPSS (Chicago, IL) to evaluate the significance of single variants and interaction of variants during in vivo association studies as well as in vitro haplotype-specific CHGB promoter/reporter activity. Haplotypes in the blood pressure extreme population were estimated from unphased diploid genotypes by use of the SNP-Expectation Maximization (SNP-EM) program, which includes omnibus likelihood ratio permutation tests 19. Comparison of haplotype frequencies between population BP extremes (hypertensive cases versus controls) was performed using the SNP-EM algorithm 20. SNP-EM estimates haplotype frequencies for each group using the EM algorithm, taking into account the probability of all possible haplotype pairs, and calculates an omnibus likelihood ratio statistic to compare haplotype frequencies between two groups (cases vs. controls), as well as a permutation test to determine significance in the face of multiple comparisons (set at 10,000 permutations). SNP-EM was used to perform a “sliding window” analysis to identify associated haplotype lengths (from 1–4 SNPs) across the locus 21, thus evaluating all possible haplotypes across the four SNPs, thereby interrogating genetic variation at the locus in an unbiased, hypothesis-free way. Additional permutation tests 22 on 3×2 contingency tables (diploid genotype versus BP status), implemented at <http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/exact.html>, were used to confirm genotype effect on the dichotomous BP trait.

For twin pair analyses, descriptive (genotype-specific mean and standard error) and inferential (chi-square, p value) statistics were computed across all of the twins, using generalized estimating equations (GEEs; PROC GENMOD) in SAS (Statistical Analysis System; Cary, NC), to account for correlated trait values within each twinship, using an exchangeable correlation matrix 23.

CHGB promoter/luciferase reporter activity assays(on-line supplement).

Generation and phenotyping of mouse Chgb targeted gene ablation (knockout) animals (on-line supplement).

Statement of responsibility

The authors had full access to and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

RESULTS

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) discovery

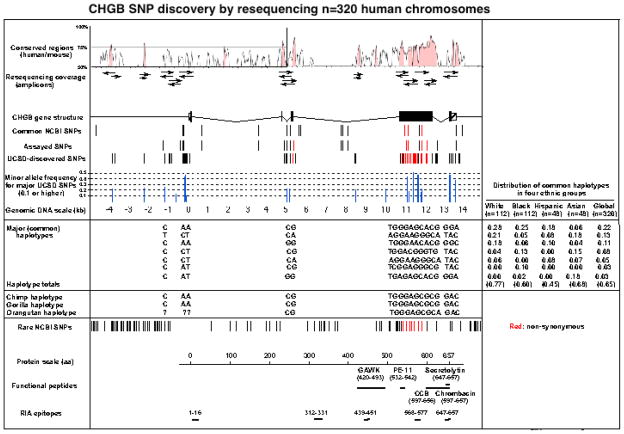

In 160 individuals of diverse biogeographic ancestries, we identified 52 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 1 single base insertion/deletions in 12 amplicons spanning a 5935 bp footprint, ~50% of which were not in the previous public databases (e.g., dbSNP) (supplementary Table 2; Figure 1). Of these, 22 SNPs were common (at minor allele frequency ≥5%); 8 SNPs with exceedingly high minor allele frequencies (>40%) were noted in the proximal promoter, exon 4, and intron 4 (Figure 1). There were 14 SNPs in the promoter region, 1 in the 5′-UTR, 21 in the coding exons, 14 in introns, and 3 in the 3′-UTR (supplementary Table 2). Global minor allele frequencies ranged from 0.6%–48.7%.

Figure 1. Human CHGB genetic diversity.

CHGB systematic SNP discovery by resequencing all exons, exon/intron borders, UTRs, and proximal promoter (in 2n=320 human chromosomes). Conserved regions between mouse and human CHGB were visualized with VISTA 44. Red rods represent non-synonymous SNPs, while black rods represent synonymous SNPs. Computationally reconstructed haplotypes (by PHASE, using 19 variants across the locus) are indicated, along with their relative frequencies in ethnogeographic groups within our sample populations. Nucleotide deletions in haplotype sequences are indicated by *. Common NCBI SNPs: SNPs in the public database with reported minor allele frequency ≥10%. Assayed SNPs: Variants whose assays were attempted in DNAs from individuals phenotyped at UCSD. ?: Data uncertainty in orangutan upstream sequence.

When comparing results across ethnicities, some SNPs were common in each of the 4 groups sampled. On the other hand, the frequencies of some SNPs differed substantially across ethnicities: e.g., A is the major allele of promoter SNP A-261T in whites, but the minor allele in blacks, Asians, and Hispanics. We also resequenced CHGB from 3 non-human primates (chimp, gorilla, orangutan) to determine the likely ancestral alleles at polymorphic sites (Figure 1); the most common human haplotype matched the chimp at 15 of 18 sites; at the remaining 3 sites (A11727G, G13383A, and A13612C), the chimp allele was found in less common human haplotypes.

SNP distribution: Haplotypes

To identify variants that are linked in the population, we inferred haplotypes from diploid genotypes at 18 common (minor allele frequency >5%) SNPs at CHGB (Figure 1), stretching ~14 kbp from the proximal promoter (C-1239T) to the 3′-UTR (C13612A). Initially using PHASE 17, we identified 7 major haplotypes spanning the locus (Figure 1), accounting for ~65% of chromosomes examined. These 7 haplotypes include common variation in coding and regulatory regions and act by linkage disequilibrium to span other regions that might influence CHGB gene function. The frequencies of these 7 haplotypes varied across ethnicities (Figure 1), with haplotype 1 the most common in whites/blacks/Hispanics, but haplotype 7 the most common in Asians.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) across the CHGB locus

We scored 11 variants (Supplementary table 3.) spanning the locus in n=468 subjects (2n=936 chromosomes) of European ancestry. To visualize patterns of SNP associations, pair-wise correlations among the 11 common SNPs were quantified as linkage disequilibrium (LD) parameter D′ by GOLD 18 across the CHGB locus. In these subjects, a single block of LD was maintained across much of the ~14 kbp locus (D′ >0.8) (Supplementary Figure 1).

CHGB genetic variation in 1182 subjects with the most extreme BP values in the population

Given the relatively high degree of LD across the locus, we selected 4 SNPs with high minor allele frequencies (each at >25%), each in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium, to span 4 structural/functional domains across the gene (promoter, intron, exon, 3′-UTR) in this case/control study. Characteristics of the 4 SNPs and their major haplotypes are shown in supplementary Figure 2 and supplementary Table 4.

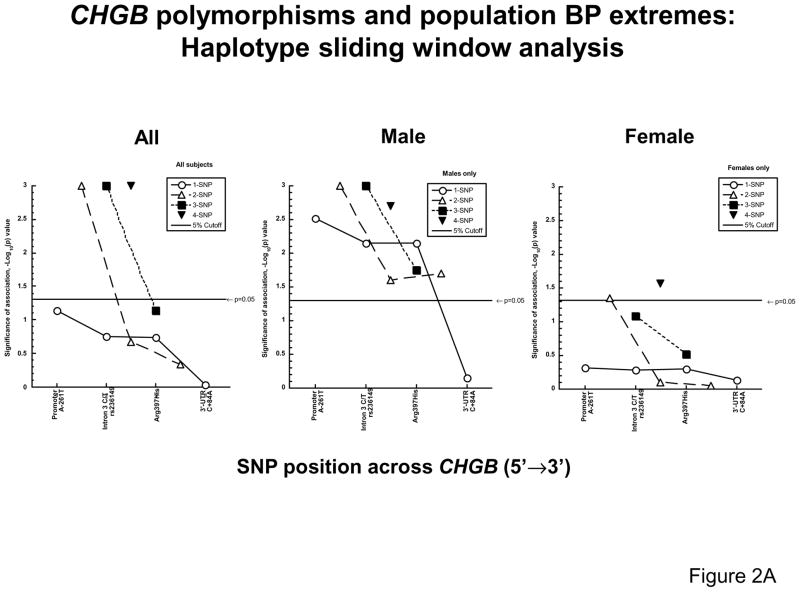

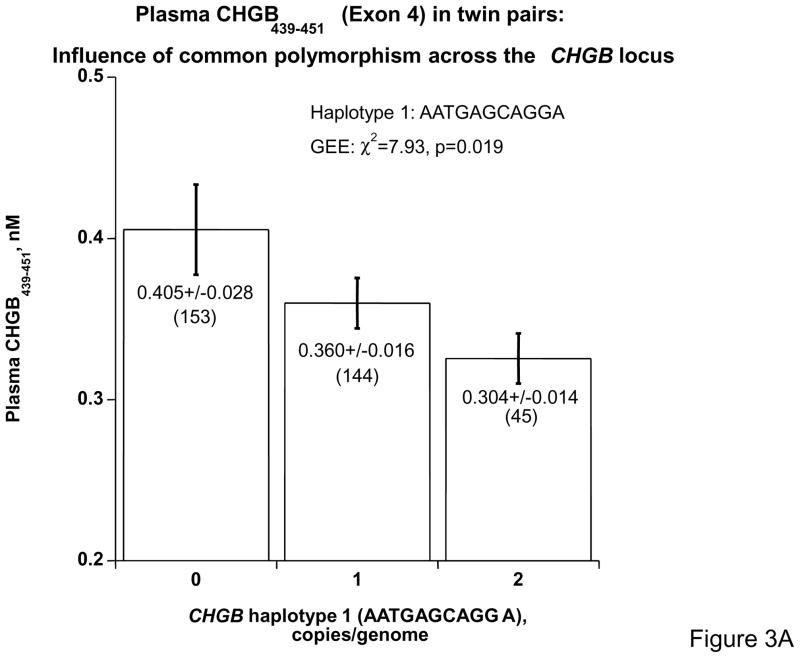

Initially, association of BP status with CHGB polymorphism was performed by a haplotype “sliding window” analysis in SNP-EM (Figure 2A). When all subjects (male and female) were included, none of the four variants alone was predictive of BP status; but the most 5′ 2-SNP haplotype (across A-261T, C10501T) associated with BP status (p<0.001); haplotypes formed from three SNPs (A-261T, C10501T, G11873A; p<0.001) or all 4 SNPs (p<0.001) were also associated with BP status.

Figure 2. Association the CHGB locus with hypertension.

2A: Haplotype sliding window analysis. Results of significance at each genotyped position or haplotypes are shown as reciprocal p values, resulting from SNP-EM (Expectation Maximization) analyses in the BP extreme populations, for the dichotomous trait of BP status (high versus low). Haplotype analyses were performed on sliding windows of 1, 2, 3 or 4 SNPs at a time.

2B: CHGB promoter polymorphism A-261T: Sex-specific effects on DBP and SBP in the population. The A (major) allele was predictive of higher DBP and SBP in the population as a whole as well as in the males alone, but not the females alone. Results were analyzed by univariate ANOVA.

When the SNP-EM analysis was confined to male subjects, single SNPs at A-261T, C10501T or G11873A were each predictive of BP status (p<0.01), with the most significant association by promoter variant A-261T (p=0.003; omnibus likelihood ratio statistic 11.36). Haplotypes composed of either 2, 3 or 4 contiguous SNPs could were associated with BP status (each at p<0.05; omnibus likelihood ratio statistics of 22.6, 29.1, and 41.1, respectively).

When the SNP-EM analysis was confined to female subjects, no single SNP was predictive of BP status by itself (p>0.05); when 2 nearby SNPs were included, only the haplotype using the 5′-most SNPs (A-261T, C10501T) was associated with BP status (p=0.05); and when 3 nearby SNPs were tested, no haplotype was predictive of BP status. Haplotypes spanning all 4 SNPs were associated with BP status (p<0.05).

Since the peak SNP and haplotype effects seemed to occur towards the 5′-end of the gene (Figure 2A), we also analyzed the association of promoter A-261T genotype and blood pressure as a quantitative trait (Figure 2B), revealing effects apparently confined to the male sex. In the promoter region (A-261T), the effect of the A-261 allele is to raise both SBP (p<0.001) and DBP (p=0.001) in males.

Coding region

We identified 21 SNPs in the coding region (Supplementary Figure 3), among which 15 non-synonymous SNPs encoded amino acid substitutions, as well as one SNP in the 5′-UTR and 3 in the 3′-UTR. Glu247Arg (0.6%) disrupts an acidic domain (Glu241-Asp249) likely to be important for trafficking of CHGB into secretory granules 2. Gly266Arg (0.6%) creates a dibasic site (Arg266Arg267), likely a recognition site for prohormone processing enzymes 24.

Most of the coding region SNPs lie toward the amino-terminal region of the protein, rather than in the carboxy-terminal region encoding the 5 best-studied peptides, i.e., GAWK, PE-11, secretolytin, CCB, or chrombacin, suggesting relative conservation of sequence in this region (Supplementary Figure 3).

Heritability and the effect of CHGB variation on gene expression in 171 twin pairs in vivo

The plasma concentrations of three CHGB regions assayed seemed to be under substantial genetic control, with h2 ranging from ~50–90% (Supplementary Figure 4), and maximal h2 for CHGB439–451 (at 91±9%, p<0.0001), encoded by exon 4 (Supplementary Figure 3).

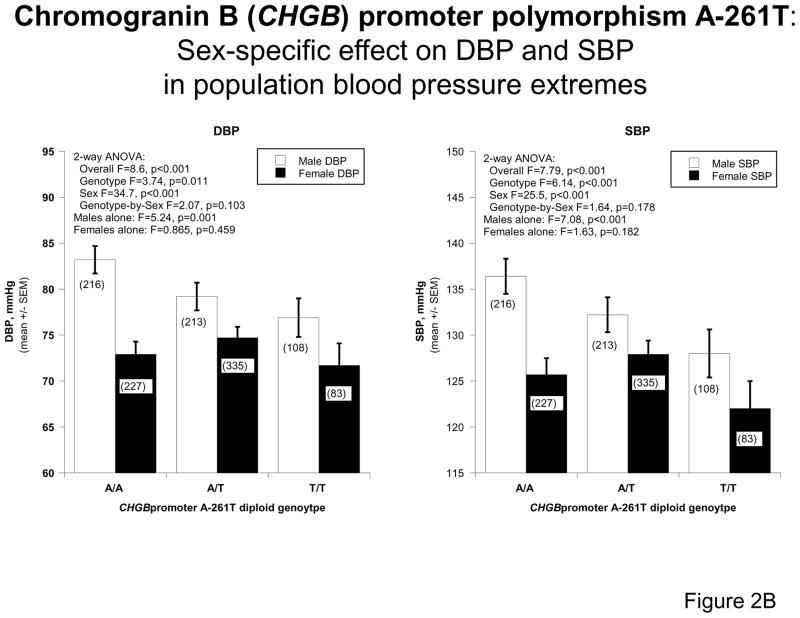

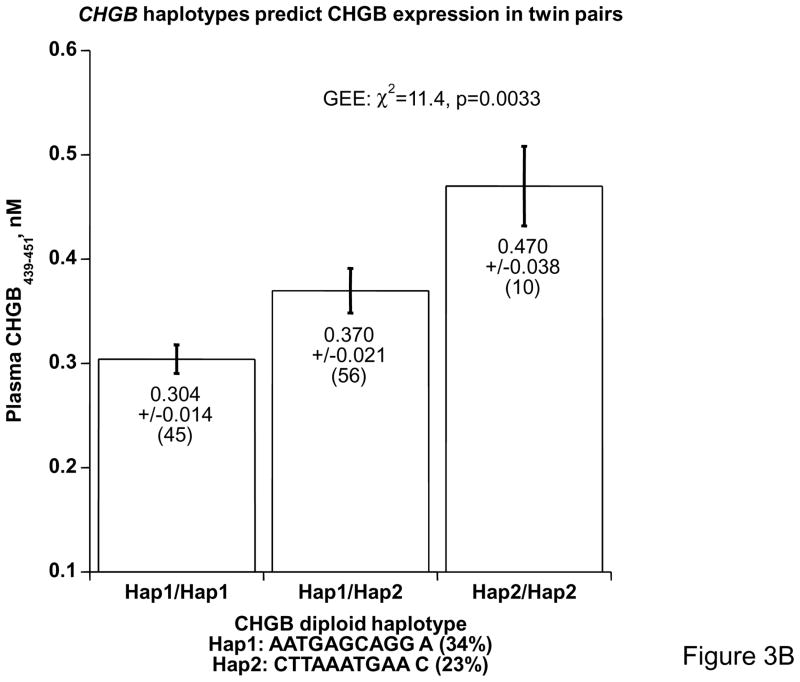

To probe the functional significance of common variation at CHGB, we examined the influence of common polymorphism on the expression of CHGB gene products in vivo. Since CHGB439–451 bears the highest heritability in CHGB fragments, we assayed plasma CHGB439–451 in n=171 twin pairs (342 individuals) typed for 11 common SNPs spanning the locus (Supplementary Table 3); these 11 variants were chosen for very dense spacing across the locus (every ~1.3 kbp across ~14 kbp), high minor allele frequency (>20% for each), and each in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium. We then inferred haplotypes in the twins, using HAP 16 and the 11 SNPs (supplementary Table 5). Copy number of the most common haplotype spanning the locus (haplotype 1, at 34% of chromosomes; AATGAGCAGGA) was predictive of plasma CHGB439–451 (p=0.019, Figure 3A): increasing copy number (0→1→2 copies/genome) progressively decreased the peptide by ~33%. When we considered haplotype pairs (diplotypes), combinations of haplotypes 1 and 2 (haplotype 2 is CTTAAATGAAC, at 23% of chromosomes) revealed a progressive increase in plasma CHGB439–451, by ~55% (p=0.0033), from haplotype 1 homozygotes through haplotype 2 homozygotes (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Coding region SNPs and human plasma CHGB.

3A: CHGB haplotypes and single nucleotide polymorphisms predict CHGB expression in twin pairs. Plasma CHGB439-451 concentrations were measured in twin pairs, and haplotypes were inferred from 11 common SNPs spanning the CHGB locus. The two most common haplotypes are shown (haplotype 1 at 34% of chromosomes, haplotype 2 at 23%). Haplotype 1. Increasing haplotype1 copy number decreases CHGB439-451 expression. Haplotype 1 bears the alleles: A-261→C10501→G11783→13612A.

3B: Diploid haplotypes (diplotypes). The two most common haplotypes were expressed as diploid haplotypes, and trait mean ± SEM values (by GEE) are shown for Hap1/Hap1 homozygotes, Hap1/Hap2 heterozygotes, and Hap2/Hap2 homozygotes. Haplotype 2 bears these alleles: −261T, 10501T, 11783A and C13612.

Twin pairs also allowed us to estimate the h2 of other “intermediate” traits for future development of hypertension 14, such as urine epinephrine excretion (at h2=32 =67.6±4.9%, n=316, p<0.0001) and the DBP response to cold stress (at h2=32±8%, n=326, p=0.0003).

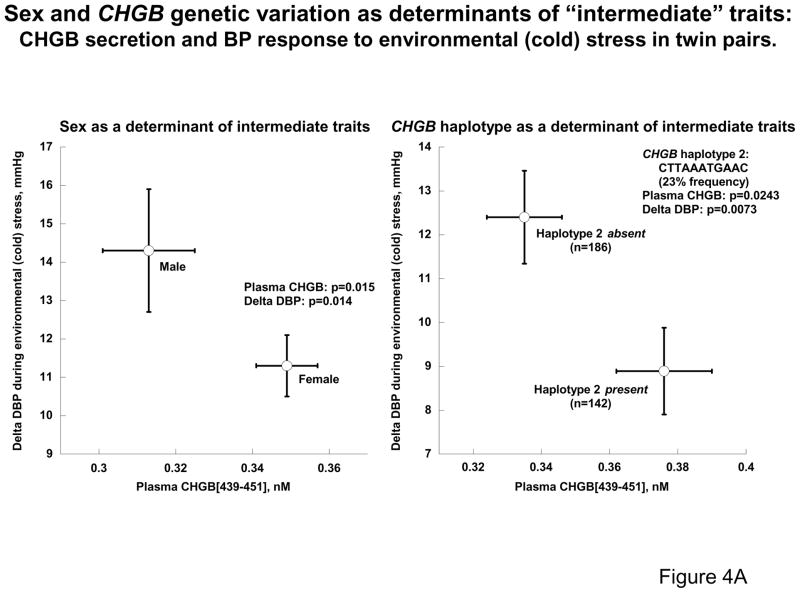

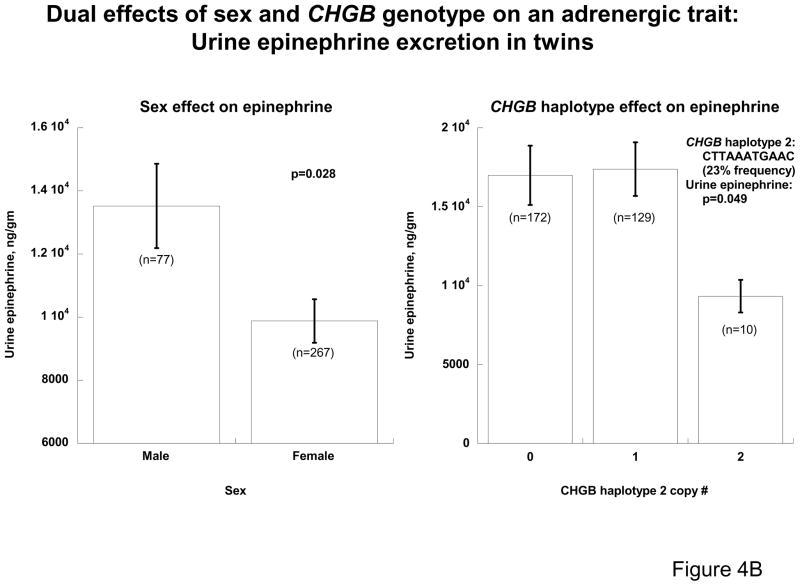

Sex influence on CHGB secretion and “intermediate” phenotypes for later development of hypertension (in 171 twin pairs)

Since sex had a profound effect on the association between CHGB genotype and resting blood pressure in the population (Figures 2A & 2B), we used our set of predominantly healthy, normotensive twin pairs and siblings to explore the effect of sex on both CHGB secretion and other early, “intermediate” phenotypes for later development of hypertension 25: the BP response to environmental (cold) stress (Figure 4A) and epinephrine secretion (Figure 4B). Plasma CHGB439-451 concentration was lower (p=0.015) in males (0.313±0.012 nM, n=203) than females (0.349±0.008 nM, n=544). By contrast, the ΔDBP was higher (p=0.014) in males (14.3±1.6 mmHg, n=62) than females (11.3±0.8 mmHg, n=236); similarly, urine epinephrine secretion was lower (p=0.028) in females (9879±686ng/gm, n=267) than males (13526±1337ng/gm, n=77). Thus women, a group at decreased risk for development of hypertension 13, displayed not only diminished pressor responses and catecholamine secretion, but also elevated CHGB biosynthesis/secretion.

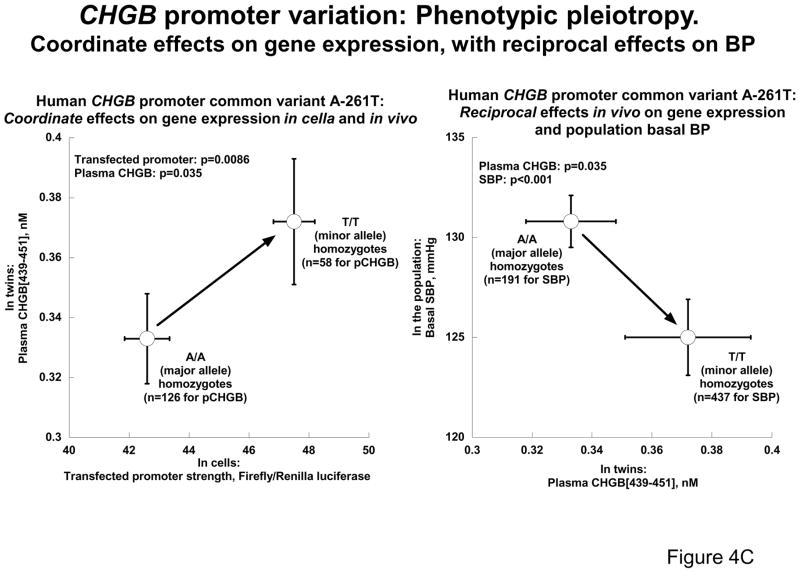

Figure 4. Sex and CHGB genetic variation: Pleiotropic effects on biochemical (CHGB439-451) and physiological “intermediate” phenotypes.

4A: Sex, CHGB genetic variation, and two intermediate traits in twin pairs: CHGB secretion and the BP response to environmental stress. CHGB haplotype 2 was inferred from 11 common SNPs across the locus. Males have lower CHGB secretion but higher ΔDBP response to cold stress (both p<0.02), while the presence of haplotype 2 (one or two copies) is predictive of both higher CHGB secretion and lower ΔDBP response (both p<0.03).

4B: Sex, CHGB genetic variation, and catecholamine secretion in twin pairs. CHGB haplotype 2 was inferred from 11 common SNPs across the locus. Males have higher urine epinephrine, while haplotype 2 homozygosity is predictive of lower urine epinephrine excretion (both p<0.05).

4C: CHGB promoter variant A-261T: Phenotypic pleiotropy. T/T (minor allele) homozygosity increases gene expression in cells, increases plasma CHGB secretion in twins, but decreases blood pressure in the population.

CHGB polymorphism: Effects on biochemical and physiological intermediate traits (in 171 twin pairs)

In the twin sample, genetic variation across CHGB (Figure 4A), as captured by common haplotype 2 spanning 11 variants (CTTAAATGAAC, at 23%), was associated with not only CHGB secretion but also the BP response to stress. Plasma CHGB439–451 concentration was lower (p=0.0243) in subjects without haplotype 2 (0.335±0.011 nM, n=186) than in those who carried one or two copies of that haplotype (0.376±0.014 nM, n=142). By contrast, the ΔDBP was higher (p=0.0073) in haplotype 2 non-carriers (12.4±1.1 mmHg, n=186) than in carriers (8.9±1.0 mmHg, n=142). Similarly, increasing CHGB haplotype 2 copy number was predictive of decreased catecholamine secretion (Figure 4B). Thus haplotype 2 seemed to affect CHGB expression and adrenergic/pressor responses inversely, suggesting that subjects with a genetically programmed (i.e., cis-QTL) increase in CHGB synthesis exhibit greater autonomic stability and thereby decreased cardiovascular risk.

CHGB promoter variation: Coordinate directional function both in cella and in vivo (twins)

Since common promoter variant A-261T associated with blood pressure (Figures 2A and 2B), we studied the effect of A-261T alleles on transfected CHGB promoter strength in chromaffin cells (Figure 4C), using a 1365 bp proximal promoter fragment driving expression of a luciferase reporter in vector pGL3-Basic, and varying the allele at position −261 from T to A by site-directed mutagenesis, followed by sequence verification. Since plasmids carry only one genotype (either T or A), we plotted both phenotype values for homozygotes (A/A or T/T) only. Transversion from A to T at −261 resulted in an increase in luciferase expression (p=0.0086), which paralleled an increase (p=0.035) in plasma CHGB439–451 expression in vivo in twins selected for -261 homozygsity: 0.333±0.015 nM in A/A homozygotes (n=126) versus 0.372±0.021 nM in T/T homozygotes (n=58). Thus, A-261T variation exerted parallel effects in cella and in vivo.

CHGB promoter variation: Reciprocal effects in vivo on gene expression and basal BP in the population

To probe the consequences of CHGB expression in vivo for long-term control of BP (Figure 4C), we plotted plasma CHGB (in twin pairs) versus resting/basal DBP (in the population BP extremes), simplifying the plot by focusing on homozygotes. The same allele (T) that raised CHGB expression also lowered population DBP (from 78.3±1.0to 74.5±1.6 mmHg, p=0.011).

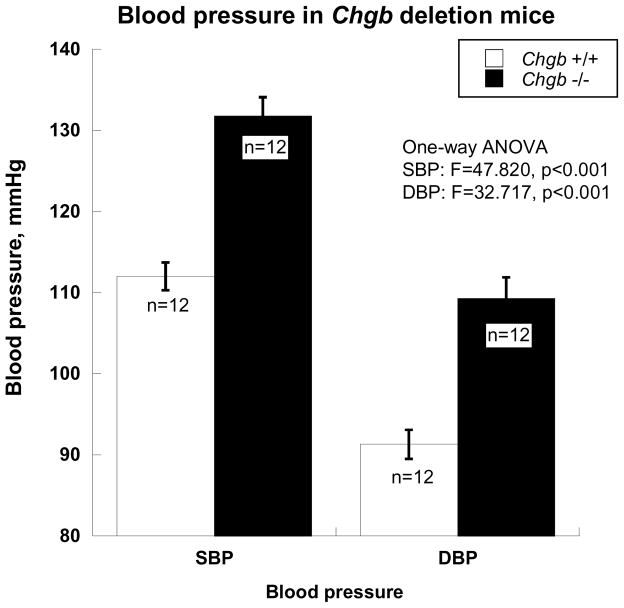

Blood pressure after targeted ablation of the Chgb gene in mice

Chgb−/− mice displayed substantially higher SBP/DBP (by ~20/~18 mmHg) than Chgb+/+ mice. SBP was 112.0±1.7 mmHg for Chgb+/+ mice (n=12), rising to 131.8±2.3 mmHg for Chgb−/− mice (n=12, F=47.8, p<0.001). DBP was 91.3±1.8 mmHg for Chgb+/+ mice (n=12) and 109.3±2.6 mmHg for Chgb−/− mice (n=12, F=32.7, p<0.001, Figure 5). This finding is consistent with the relationship between plasma CHGB439–451 concentration and blood pressure that we found in humans (Figure 4C).

Figure 5. Blood pressure in Chgb deletion mice.

Blood pressure was measured over 7 days (3 times/day, or 21 times) in each animal. After Chgb deletion, both DBP and SBP increased significantly (p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Overview

Patients with hypertension often exhibit increased sympathetic activity,26, 27 and people with sympathetic overactivity tend to develop hypertension28, 29. Suppression of Chgb expression in neuroendocrine PC12 cells leads to a reduction in the number of catecholamine secretory granules, whereas ectopic expression of Chgb in non-neuroendocrine cells, which normally do not contain any secretory machinery, leads to granule biogenesis7. In light of the emerging secretory biology of CHGB, we undertook the present study, using the tools of genome technology and statistical genetics in order to probe how heredity shapes human functional responses in the sympathetic neuroeffector junction, using CHGB as a likely focal point in the pathogenesis of essential hypertension.

Polymorphic profile at the CHGB locus

Systematic identification of genetic variants at a candidate locus is a strategy for disease association30. At CHGB, we therefore resequenced all 5 exons, adjacent intronic regions, and the proximal promoter in n=160 human subjects from 4 biogeographic ancestry groups, thereby identifying 53 polymorphisms over a 5935 bp footprint, or just under one variant every 100 bp. The genetic diversity that we report at CHGB is somewhat more comprehensive than that previously reported for 32 individuals from the Han Chinese population (15 SNPs)31, or 24 individuals of Japanese ancestry (24 SNPs)32, as a consequence of the greater number of individuals studied, the multiethnic samples, and the greater resequencing footprint, but no inconsistencies were noted. In the previous Asian reports 31, 32, CHGB polymorphisms (mainly towards the 3′ end of the gene) were associated with schizophrenia; since the population prevalence of schizophrenia is only ~0.4–0.6%33, our resequenced sample of n=160 normotensive and hypertensive individuals from southern California does not have statistical power to detect such an effect on neuropsychiatric disease. While the pattern of linkage disequilibrium across the CHGB locus suggested a extended single block of LD across the ~14 kbp locus in individuals of European ancestry (Supplementary Figure 1), allele frequencies did differ substantially across the 4 biogeographic ancestries sampled (Supplementary Table 2).

Strategies for hypertension risk: Heritability and CHGB variant effects on multiple “intermediate phenotypes” in twin pairs

We developed series of twin pairs of southern California, typed for traits likely to contribute to later development of hypertension 11. The twin data offer the advantage of determining trait heritability (h2), the fraction of phenotypic variance accounted for by genetic variance, a logical estimator of the tractability of any trait to genetic investigation; indeed, the twin traits were substantially heritable (Supplementary Figure 4).

Multiple autonomic phenotypes in the twins, both biochemical and physiological, allowed construction of an integrated picture of the effects of genetic variation at CHGB on a very proximate biochemical phenotype, plasma CHGB concentration (Figure 4A); a later biochemical consequence, epinephrine excretion (Figure 4B); a more distant physiological consequence, change in BP during environmental stress (Figure 4A); and finally basal/resting BP in the population (Figure 2B).

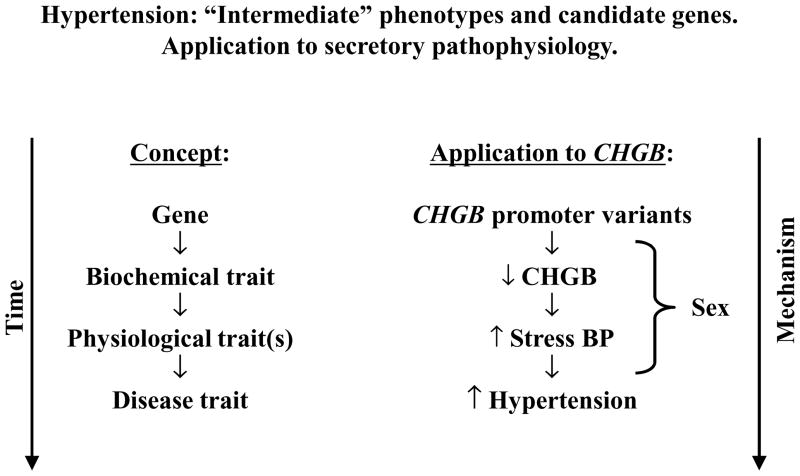

Intriguingly, the same CHGB genetic variants that increased CHGB storage and secretion (Figure 4A) also decreased catecholamine secretion (Figure 4B), the sensitivity of BP to environmental stress (Figure 4A), and finally basal BP in the population (Figure 2B). A unifying hypothesis is presented in Figure 6. Such a hypothetical framework is supported by the experimental findings of Huh et al 7, who found by over- and under-expression of Chgb in catecholaminergic cells that Chgb regulates the biogenesis of hormone storage granules of the regulated secretory pathway. Absence of Chgb would therefore be predicted to disrupt the pathway, perhaps leading to constitutive (unregulated or autonomous) transmitter release. Indeed, we observed excess catecholamine secretion (Figure 4B) and autonomic BP instability (Figure 4A) in subjects with genetically programmed decrease in CHGB biosynthesis and secretion (Figure 4A). Evidence in cella 34 and in vivo35 also supports a critical role for the CHGB paralog CHGA in the biogenesis of catecholamine storage vesicles; indeed, targeted ablation of CHGA 35 results in dysregulated catecholamine storage and secretion, accompanied by systemic hypertension.

Figure 6. Hypertension: “Intermediate” phenotypes and candidate genes. Application to secretory pathophysiology.

CHGB promoter polymorphisms lead to variation of gene expression, thus changing the secretion of epinephrine, which alters the blood pressure response to environmental stress. After decades, fixed blood pressure elevation (hypertension) may occur in genetically susceptible subjects.

In this report, we focused primarily upon two indices of sympathoadrenal function: catecholamine secretion (Figure 4B) and the BP response to environmental stress (Figure 4A). Since CHGB has such a widespread occurrence in amine and peptide storage vesicles 2, 3, 9, 10, 36, 37, it is likely that additional consequences of CHGB genetic variation might be uncovered in other branches (e.g., parasympathetic) of the autonomic system, or the wider neuroendocrine system. However, such alterations are beyond the scope of this initial report.

Established hypertension and CHGB genetic variation: Population BP extremes

To pursue the genetic involvement in established essential hypertension, we developed a powerful resource in a sample set consisting of individuals with extremely high and low blood pressures. From a population sample of over 53,000 people, we ascertained >1,100 age-, gender- and ethnicity-matched individuals from the upper and lower 5th percentiles of the population BP distribution13.

Using CHGB polymorphisms spanning the locus (Supplementary Figure 2), we took a haplotype “sliding window” approach in SNP-EM 19 to test the effects of CHGB regions on the hypertension trait. We found that variation across the locus was predictive of BP category (Figure 2A), as well as the SBP and DBP quantitative traits (haplotypes, Figure 2B), but the effects were substantially more impressive in males than females, and the genetic effects in males seemed to peak towards the 5′ (promoter) end of the gene, with the most significant single effect at promoter variant A-261T.

When we studied the effect of A-261T variation on the SBP/DBP quantitative traits (Figure 2B), once again the effects were most impressive for males (p<0.001/p=0.001) than females (p=0.182, p=0.459). The profound difference in genetic effects between sexes led us to explore the effects of sex at earlier stages in the hypothetical phenotypic chain between gene and the ultimate disease trait (Figure 6; see below). Of note, sex itself had a profound effect upon BP in the population (Figure 2B), consistent with epidemiological findings over several decades 38.

Although we undertook CHGB polymorphism discovery systematically across several biogeographic ancestry groups (Supplementary Tables 1&2; Figure 1), we conducted CHGB marker-on-trait blood pressure studies in subjects of a single ancestry: European (Figure 2A & 2B). We restricted our initial analyses to subjects of one ancestry since allelic association studies can be susceptible to artifactual conclusions resulting from even inapparent population admixture 39. Studies of additional ethnic or population groups will be required to evaluate whether our CHGB results are of more general importance in the overall population.

Sex and genetic risk of hypertension: “Intermediate” and ultimate disease traits

Sex exerted profound effects on not only the BP trait in general (Figure 2B) 38 but also the BP response to CHGB genetic variation (Figure 2A & 2B). Previously we have noted significant gene-by-sex interactions on BP in the population, as well as sex differences in the response to adrenergic drug provocations 40, 41. To understand how sex might influence the genetic predisposition to hypertension, we studied the effect of sex on each of the “intermediate phenotypes” influenced by CHGB genetic variation. We found that sex systematically influenced each such trait, in ways predicted to reduce risk of future development of hypertension: females exhibited increased CHGB expression (Figure 4A, reduced epinephrine secretion (Figure 4B), and reduced pressor responses to environmental stress (Figure 4A). We noted effects of CHGB genetic variation on BP in males though not females (Figures 2A & 2B), and observed that autonomic traits, both biochemical (Figure 4A) and physiological (Figures 4A & 4B), differed in males and females; nonetheless, we did not statistically document significant CHGB gene-by-sex interaction on BP (Figure 2B), suggesting caution during interpretation of sex-specific roles of genes in cardiovascular trait determination.

Although we measured BP before and after environmental stress (Figure 4A), we measured catecholamines only prior to stress. However, previous longitudinal studies indicate that the pressor (BP) response to cold is an effective predictor of future development of hypertension 42, although the predictive value of such early stress tests seems to be more apparent in males 43. Thus, at every stage of the putative pathogenic chain (Figure 6) between CHGB genetic variation and the development of hypertension, sex may be involved as a potential modifier of gene effects.

Role of the CHGB promoter: Coordinate CHGB genetic effects in cella and in vivo

Since BP in the population was best associated with genetic variation in the CHGB promoter region (Figure 2A & 2B), we ligated a ~1.4 kb proximal promoter fragment to a luciferase reporter and tested the effect of the A-261T variant on promoter activity in transfected chromaffin cells (Figure 4C). We found that the minor (T) was significantly more active than the A allele in programming transcription; of further note was the coordinate effect of the two alleles in cella and in vivo: the T allele not only increased transcription in chromaffin cells, but also increased plasma CHGB in twin pairs. These results are consistent with genetic variation in the CHGB promoter initiating the entire cascade of phenotypic events illustrated in our hypothetical schema (Figure 6). Loss-of-function CHGB promoter variants (such as allele A at A-261T) would give rise to decreased CHGB expression, thereby unleashing sympathochromaffin activity, leading to exaggerated pressor responses to environmental stressors, and ultimately fixed systemic hypertension.

Blood pressure in mice with targeted ablation of the Chgb locus

Since we found inverse effects of CHGB expression on catecholamine secretion (Figure 4B) pressor responses (Figure 4A), and since the CHGB genotype associated with lower CHGB expression in cella (Figure 4C) and in vivo (Figure 4C) was also predictive of higher resting SBP/DBP in the population (Figure 4C), we hypothesized that experimental disruption of CHGB expression would elevate BP. We tested this hypothesis by targeted ablation of the Chgb locus, and as predicted found substantial elevations in both SBP (by ~20 mmHg) and DBP (~18 mmHg) in Chgb(−/−) mice. Thus, experimental evidence further strengthens our clinical conclusions (Figure 6) that CHGB genetic variation initiates a cascade of events ultimately resulting in blood pressure disturbances in the population.

Conclusions and perspectives

Common genetic variation at the CHGB locus, especially in the proximal promoter, influences CHGB expression as well as catecholamine secretion in vivo, and later the early heritable responses to environmental stress, and finally resting/basal BP in the population (Figure 6 hypothesis). These changes are modified at each pathophysiological level by the influence of sex. Although causal inferences in this proposed chain of events are not yet established, the pathway illustrated in Figure 6 does yield testable predictions for experimental verification. These results point to new molecular strategies for probing autonomic control of the circulation, and ultimately the susceptibility to and pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease states such as hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support: Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CHGA

Chromogranin A

- CHGB

Chromogranin B

- Chgb

Mouse chromogranin B

- cSNP

Coding sequence single nucleotide polymorphism

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- GOLD

Graphical Observation of Linkage Disequilibrium

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

- RIA

Radioimmunoassay

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures: None.

Author Disclosures

Kuixing Zhang: No disclosures

Fangwen Rao: No disclosures

Brinda Rana: No disclosures

Jiaur Gayen: No disclosures

Federico Calegari: No disclosures

Angus King: No disclosures

Patrizia Rosa: No disclosures

Wieland Huttner: No disclosures

Mats Stridsberg: No disclosures

Manjula Mahata: No disclosures

Sucheta Vaingankar: No disclosures

Vafa Vahboubi: No disclosures

Rany Salem: No disclosures

Juan Rodriguez-Flores: No disclosures

Maple Fung: No disclosures

Douglas Smith: No disclosures

NIcholas Schork: No disclosures

Michael Ziegler: No disclosures

Laurent Taupenot: No disclosures

Sushil Mahata: No disclosures

Daniel T. O'Connor: No disclosures

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The manuscript and its contents are confidential, intended for journal review purposes only, and not to be further disclosed.

References

- 1.Binder A. A review of the genetics of essential hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22:176–184. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3280d357f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taupenot L, Harper KL, O’Connor DT. The chromogranin-secretogranin family. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1134–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosa P, Hille A, Lee RW, Zanini A, De Camilli P, Huttner WB. Secretogranins I and II: two tyrosine-sulfated secretory proteins common to a variety of cells secreting peptides by the regulated pathway. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1999–2011. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.5.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falkensammer G, Fischer-Colbrie R, Winkler H. Biogenesis of chromaffin granules: incorporation of sulfate into chromogranin B and into a proteoglycan. J Neurochem. 1985;45:1475–1480. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor DT, Frigon RP, Sokoloff RL. Human chromogranin A. Purification and characterization from catecholamine storage vesicles of human pheochromocytoma. Hypertension. 1984;6:2–12. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.6.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schober M, Fischer-Colbrie R, Schmid KW, Bussolati G, O’Connor DT, Winkler H. Comparison of chromogranins A, B, and secretogranin II in human adrenal medulla and pheochromocytoma. Lab Invest. 1987;57:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huh YH, Jeon SH, Yoo SH. Chromogranin B-induced secretory granule biogenesis: comparison with the similar role of chromogranin A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40581–40589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill BM, Barbosa JA, Dinh TQ, Garrod S, O’Connor DT. Chromogranin B: isolation from pheochromocytoma, N-terminal sequence, tissue distribution and secretory vesicle processing. Regul Pept. 1991;33:223–235. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(91)90216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Natori S, Huttner WB. Chromogranin B (secretogranin I) promotes sorting to the regulated secretory pathway of processing intermediates derived from a peptide hormone precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4431–4436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahapatra NR, Mahata M, Datta AK, Gerdes HH, Huttner WB, O’Connor DT, Mahata SK. Neuroendocrine cell type-specific and inducible expression of the chromogranin B gene: crucial role of the proximal promoter. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3668–3678. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.10.7725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connor DT, Kailasam MT, Kennedy BP, Ziegler MG, Yanaihara N, Parmer RJ. Early decline in the catecholamine release-inhibitory peptide catestatin in humans at genetic risk of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1335–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200207000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waalen J, Felitti V, Gelbart T, Ho NJ, Beutler E. Prevalence of coronary heart disease associated with HFE mutations in adults attending a health appraisal center. Am J Med. 2002;113:472–479. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rana BK, Insel PA, Payne SH, Abel K, Beutler E, Ziegler MG, Schork NJ, O’Connor DT. Population-based sample reveals gene-gender interactions in blood pressure in White Americans. Hypertension. 2007;49:96–106. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252029.35106.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao F, Zhang L, Wessel J, Zhang K, Wen G, Kennedy BP, Rana BK, Das M, Rodriguez-Flores JL, Smith DW, Cadman PE, Salem RM, Mahata SK, Schork NJ, Taupenot L, Ziegler MG, O’Connor DT. Tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis: discovery of common human genetic variants governing transcription, autonomic activity, and blood pressure in vivo. Circulation. 2007;116:993–1006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.682302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halperin E, Eskin E. Haplotype reconstruction from genotype data using Imperfect Phylogeny. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1842–1849. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens M, Donnelly P. A comparison of bayesian methods for haplotype reconstruction from population genotype data. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1162–1169. doi: 10.1086/379378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abecasis GR, Cookson WO. GOLD--graphical overview of linkage disequilibrium. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:182–183. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fallin D, Schork NJ. Accuracy of haplotype frequency estimation for biallelic loci, via the expectation-maximization algorithm for unphased diploid genotype data. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:947–959. doi: 10.1086/303069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fallin D, Cohen A, Essioux L, Chumakov I, Blumenfeld M, Cohen D, Schork NJ. Genetic analysis of case/control data using estimated haplotype frequencies: application to APOE locus variation and Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Res. 2001;11:143–151. doi: 10.1101/gr.148401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaykin DV, Westfall PH, Young SS, Karnoub MA, Wagner MJ, Ehm MG. Testing association of statistically inferred haplotypes with discrete and continuous traits in samples of unrelated individuals. Hum Hered. 2002;53:79–91. doi: 10.1159/000057986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarkson D, Fan Y-A, Joe H. A remark on algorithm 643: FEXACT: An algorithm for performing Fisher’s exact test in RxC contingency tables. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 1993;19:484–488. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Do KA, Broom BM, Kuhnert P, Duffy DL, Todorov AA, Treloar SA, Martin NG. Genetic analysis of the age at menopause by using estimating equations and Bayesian random effects models. Stat Med. 2000;19:1217–1235. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000515)19:9<1217::aid-sim421>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eskeland NL, Zhou A, Dinh TQ, Wu H, Parmer RJ, Mains RE, O’Connor DT. Chromogranin A processing and secretion: specific role of endogenous and exogenous prohormone convertases in the regulated secretory pathway. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:148–156. doi: 10.1172/JCI118760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folkow B. Physiological aspects of primary hypertension. Physiol Rev. 1982;62:347–504. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1982.62.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlaich MP, Lambert E, Kaye DM, Krozowski Z, Campbell DJ, Lambert G, Hastings J, Aggarwal A, Esler MD. Sympathetic augmentation in hypertension: role of nerve firing, norepinephrine reuptake, and Angiotensin neuromodulation. Hypertension. 2004;43:169–175. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000103160.35395.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambert E, Straznicky N, Schlaich M, Esler M, Dawood T, Hotchkin E, Lambert G. Differing pattern of sympathoexcitation in normal-weight and obesity-related hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;50:862–868. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.094649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palatini P, Longo D, Zaetta V, Perkovic D, Garbelotto R, Pessina AC. Evolution of blood pressure and cholesterol in stage 1 hypertension: role of autonomic nervous system activity. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1375–1381. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000234118.25401.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Vogli R, Brunner E, Marmot MG. Unfairness and the social gradient of metabolic syndrome in the Whitehall II Study. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cowley AW., Jr The genetic dissection of essential hypertension. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:829–840. doi: 10.1038/nrg1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang B, Tan Z, Zhang C, Shi Y, Lin Z, Gu N, Feng G, He L. Polymorphisms of chromogranin B gene associated with schizophrenia in Chinese Han population. Neurosci Lett. 2002;323:229–233. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iijima Y, Inada T, Ohtsuki T, Senoo H, Nakatani M, Arinami T. Association between chromogranin b gene polymorphisms and schizophrenia in the Japanese population. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldner EM, Hsu L, Waraich P, Somers JM. Prevalence and incidence studies of schizophrenic disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:833–843. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Courel M, Rodemer C, Nguyen ST, Pance A, Jackson AP, O’Connor DT, Taupenot L. Secretory granule biogenesis in sympathoadrenal cells: identification of a granulogenic determinant in the secretory prohormone chromogranin A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38038–38051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahapatra NR, O’Connor DT, Vaingankar SM, Hikim AP, Mahata M, Ray S, Staite E, Wu H, Gu Y, Dalton N, Kennedy BP, Ziegler MG, Ross J, Mahata SK. Hypertension from targeted ablation of chromogranin A can be rescued by the human ortholog. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1942–1952. doi: 10.1172/JCI24354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portela-Gomes GM, Stridsberg M. Region-specific antibodies to chromogranin B display various immunostaining patterns in human endocrine pancreas. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:1023–1030. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahapatra NR, Mahata M, Ghosh S, Gayen JR, O’Connor DT, Mahata SK. Molecular basis of neuroendocrine cell type-specific expression of the chromogranin B gene: Crucial role of the transcription factors CREB, AP-2, Egr-1 and Sp1. J Neurochem. 2006;99:119–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knowler WC, Williams RC, Pettitt DJ, Steinberg AG. Gm3;5,13,14 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: an association in American Indians with genetic admixture. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;43:520–526. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King D, Etzel JP, Chopra S, Smith J, Cadman PE, Rao F, Funk SD, Rana BK, Schork NJ, Insel PA, O’Connor DT. Human response to alpha2-adrenergic agonist stimulation studied in an isolated vascular bed in vivo: Biphasic influence of dose, age, gender, and receptor genotype. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77:388–403. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kneale BJ, Chowienczyk PJ, Brett SE, Coltart DJ, Ritter JM. Gender differences in sensitivity to adrenergic agonists of forearm resistance vasculature. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1233–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00849-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasagi F, Akahoshi M, Shimaoka K. Relation between cold pressor test and development of hypertension based on 28-year follow-up. Hypertension. 1995;25:71–76. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Markovitz JH, Raczynski JM, Wallace D, Chettur V, Chesney MA. Cardiovascular reactivity to video game predicts subsequent blood pressure increases in young men: The CARDIA study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:186–191. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199803000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayor C, Brudno M, Schwartz JR, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Frazer KA, Pachter LS, Dubchak I. VISTA : visualizing global DNA sequence alignments of arbitrary length. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:1046–1047. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.