Abstract

Engagement of high-risk adolescents and their families in treatment is a considerable challenge for service providers and agencies. Despite its importance, little research has been conducted that explores this important treatment process. To address this gap, a test of an innovative method to improve engagement in family therapy was undertaken. Findings of this study of 42 intervention group families and 41 comparison group families (N=83) suggest that augmenting in-home family therapy with short and creative experiential activities can significantly increase engagement and retention in treatment. Further research of engagement as a mechanism of change in family-based treatment is needed.

Keywords: high-risk youth, family therapy, treatment engagement, treatment retention, experiential treatment methods

Introduction

Engagement and retention of high-risk adolescents and their families is a serious challenge for providers in community social service agencies. Research on rates of engagement has shown that 40-60% of families who begin services terminate prematurely (Coatsworth, Santisteban, McBride, & Szapocznik, 2001) and only 22% of families seeking treatment for a youth behavior problem actually complete initial assessments (Szapocznik, Perez-Vidal, Brickman, Foote, & et al., 1988). Because clients who inconsistently participate in the therapeutic process and prematurely terminate from treatment are less likely to successfully attain treatment goals (Dakof, Tejeda, & Liddle, 2001), providers need therapeutic tools to improve engagement and retention strategies.

Despite the need for understanding the critical components of successful treatment outcomes, little is known concerning the mechanisms involved in the process of treatment engagement and retention (Kazdin & Nock, 2003). In an effort to address this gap, this study reports on a test of an innovative method to improve engagement and retention in family therapy sessions in comparison to family therapy treatment as usual. Experiential activities were incorporated in family therapy sessions delivered in the family's home environment. These activities were developed as creative techniques designed to increase youth and families' participation in treatment sessions, improve their capacity for relationship building, and increase the likelihood of treatment completion.

Engagement and Retention

Engagement is a complex and crucial component of effective treatment that increases retention in services - a requirement for successful outcomes and behavior change (Simpson, Joe, Rowan-Szal, & Greener, 1995). Engagement is typically defined across general dimensions of therapeutic involvement and participation during treatment. Clients who are engaged in the treatment process are more likely to bond with therapists, endorse treatment goals, and participate to a greater degree during treatment (Broome, Joe, & Simpson, 2001). Providers who actively work to increase client engagement are likely to build stronger alliances with their clients and elicit greater client investment in the treatment process (Dearing, Barrick, Dermen, & Walitzer, 2005).

Retention refers to the duration of treatment and represents a global indicator of the dose of treatment (Joe, Simpson, & Broome, 1998). Among clients who initiate treatment, retention has been shown to be a challenging clinical task (Coatsworth et al., 2001), but has been shown to be the single best predictor of positive outcomes (Joe et al., 1998). Clients who leave services prematurely are less likely to show the clinical gains found among service completers (Stanton & Shadish, 1997) and 40%-60% of adolescents who begin treatment terminate prematurely (Kazdin & Wassell, 1999). Thus, retention is an important area of clinical focus.

In-home Family Therapy

Considerable empirical support confirms the effectiveness of including family members in therapy with adolescents (Liddle et al., 2001; Stanton & Shadish, 1997). In addition, delivery of family therapy in the home of clients has also been shown to significantly increase attendance and participation of adolescents and their families in therapeutic sessions when compared to office-based therapy (Slesnick & Prestopnick, 2004). Home-based family therapy has been found more effective than peer groups (Liddle et al., 2001), parent education (Joanning, Quinn, & Mullen, 1992), multi-family interventions (Liddle, 1995), and individual counseling (Henggeler et al., 1991).

Researchers and practitioners have noted that barriers to families' seeking and engaging in traditional office-based family therapy include the lack of reliable transportation, inconsistent or late work schedules, few financial resources, and child care difficulties (Kazdin & Wassell, 1999). Home-based services address these barriers and have been shown to improve the therapeutic alliance, compliance with treatment requirements, and engagement (Lay, Blanz, & Schmidt, 2001).

Incorporating creative approaches in home-based family therapy has also been suggested as a means of increasing families' engagement and ultimately improving family-child interactions (Gil & Sobol, 2005). Experiential techniques are creative activities that focus on involvement and interaction between youth and parents rather than simply talking and discussing problems. Experiential “family play” techniques may be uniquely beneficial for in-home family therapy as they provide clinicians with opportunities to view families' interaction patterns and join with them in creative ways. Experiential strategies create more interest than verbal discussions alone and offer families new channels for communication (Cheung, 2006).

As the above research suggests, there is empirical support for home-based family therapy; however, methods to increase engagement and retention remain largely untested. To address this gap, this study tested experiential activities within home-based family therapy in comparison to family therapy delivered in a more typical office-based setting without the inclusion of experiential methods. Families' engagement and retention in treatment are compared across intervention and comparison groups

Methods

Participants

Referrals to the study were obtained from a social service agency in central Texas that serves families seeking assistance for an adolescent child struggling with delinquency, truancy, family conflict, and/or running away. Following the admission/intake process, agency staff presented families with the opportunity to learn about the study. Inclusion criteria for recruitment were: (1) the identified youths were 12-17 years of age at the time they sought services and were living at home, (2) the family resided within a 30-mile radius of the social service agency, and (3) at least one parent was willing to participate in family therapy sessions and provide consent for the youth to participate.

Parents and youth who agreed to be contacted by research staff for possible participation in the study were provided a full explanation of the study. Typically these contacts were made over the phone, followed by a visit to the family's home to complete the written consent/assent process. Prior to contacting the family, research staff used an over-flow design to determine the group to which the family would be invited to participate. Because only two therapists delivered the home-based family therapy intervention, families were offered participation in the intervention group only if an intervention group counselor had an available opening; otherwise, they were offered participation in the comparison group who received services as usual.

Procedures & Treatment Methods

Once the family had verbally agreed to participate, the written consent, assents, and pretests were completed in the family's home. One parent and the identified youth completed questionnaires that included various standardized measures. Following the family's completion of treatment (approximately 12 weeks), a posttest was conducted that included measures nearly identical to those on the initial questionnaire. In addition, researchers documented the number of sessions each family attended over the 12 week period. Youth and parents in both conditions received compensation for their time to complete questionnaires.

Family Therapy Modality for Intervention and Comparison Conditions

Social service agencies throughout Texas who receive specific grant funding to provide treatment to families with high-risk adolescents are required to utilize and receive continuous training in solution-focused family therapy. The solution-focused approach is a change-oriented intervention that uses a strengths-based approach. Therapists encourage clients to explore what they want to be different in their lives (goals) and help to identify client resources and strengths that can be used to achieve those goals (Berg & DeJong, 1996). Recent meta-analyses of studies employing solution-focused methods delivered within community settings have indicated this approach achieves positive results in family settings when compared to “treatment as usual” (Kim, 2008). Family therapy sessions are typically provided in office-based settings by Masters of Social Work-level therapists who received monthly training and supervision concerning solution-focused methods; all comparison group participants received therapy sessions in office-based settings.

Intervention Group - Family Therapy enhanced with experiential activities in home setting

The intervention condition included the same core solution-focused family therapy as described above; however, all sessions took place in clients' homes and included the addition of experiential activities. This enhanced treatment consisted of conducting one of nineteen experiential activities during each in-home family therapy session, followed by discussions between family members and therapists as directed by the solution-focused approach. The experiential and skill-building exercises were developed to target specific individual and/or family problems, such as expressing feelings, coping, building relationships, and communication. Two Masters of Social Work-level therapists (one male, one female) with more than nine years of experience provided treatment for this intervention group. Each had advanced clinical practice experience and received on-going, monthly training and supervision related to solution-focused methods and specific training related to delivery of the experiential activities. Each therapist selected the activity s/he felt was best able to promote achievement of identified goals during home-based family therapy sessions.

Measures

Retention in treatment was measured by the number of sessions completed by each family. In addition to monitoring retention, parents and youth in both groups completed questionnaires at pre- and post-treatment to measure treatment engagement.

Various aspects of engagement were assessed using The Client Evaluation of Self & Treatment (CEST). This measure was designed to monitor clients' needs and performance and determine changes from pre to post treatment on various dimensions of the treatment process (Joe, Broome, Rowan-Szal, & Simpson, 2002). The CEST consists of 144 items that measure five dimensions of treatment: treatment motivation, treatment process, psychological functioning, social functioning, and social network support. Examination of the psychometric properties of the CEST showed adequate reliability (α ≥ .70) for the subscales and good construct validity (Joe et al., 2002). For this current analysis, only treatment process variables are reported.

Data Analysis

Following descriptive analyses, chi-square and t-tests were conducted to determine differences between intervention and comparison groups for youth and parent sample characteristics. Retention rates were calculated based on the number of family sessions attended. T-tests were then conducted to determine differences between groups on measures of engagement (satisfaction, participation, and counselor rapport).

Results

Sample Demographics

The study sample included 83 families: 42 intervention and 41 comparison families. Youth in both groups were about 14 years of age (SD±1.5); parents were approximately 42 years of age (SD±9.4). Participating families were predominantly Hispanic/Latino (N=44, 53%), White (N=14, 17%) or African American (N=11, 13%). Most parents were employed full-time (N=42, 52%), had some college education (N=39, 47%), and were two-parent families (N=49, 59%). Few significant differences were found between intervention and comparison group characteristics; however, intervention group parents were significantly older (M=44.1, SD±9 years) than comparison group parents (M=39.8, SD±9.5 years, t = -2.03(df=81), p≤.05; intervention group families had fewer children (M=2.14, SD±1.0) than did comparison families (M=2.61, SD±1.1, t =2.05(df=81), p≤.05, and fewer intervention families had two parents in the home (47.6%) than comparison families (70.7%), χ2(df=1)=4.58, p ≤.05.

Retention in Treatment

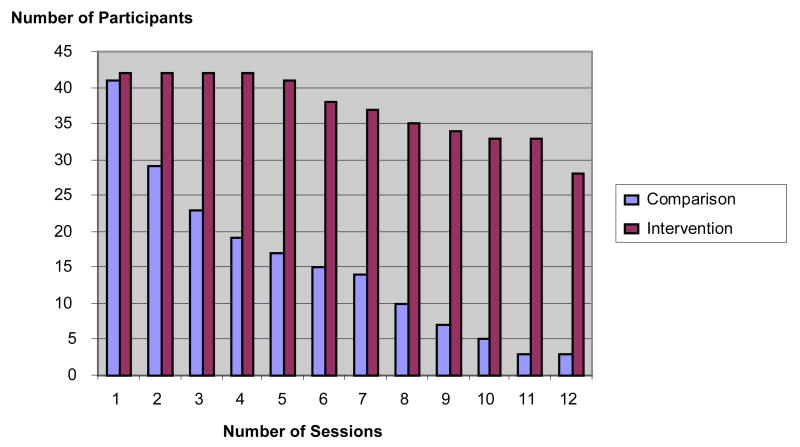

Participants who received home-based family therapy enhanced with experiential activities remained in treatment dramatically longer than the comparison group. Analyses of treatment retention (see Figure 1) showed that 80% (n=33) of intervention families completed at least 11 sessions and 67% (n=28) completed all 12 sessions. Among comparison families, only 7% (n=3) completed 11 sessions and 7% (n=3) completed all 12 sessions. The majority of comparison families (53%; n=23) only completed 3 sessions. The average number of sessions for the intervention group was 9.6 (SD=3.1) and 4.4 (SD=3.9) for the comparison group, a statistically significant difference, t =-6.66(df=81), p<.001.

Figure 1. Retention by Intervention and Comparison Groups.

Engagement Measures

Differences between intervention and comparison groups on measures of engagement were assessed following families' final treatment session. Findings indicated that parents in the intervention group reported greater satisfaction with treatment (M=41.6, SD±6.4) than did parents in the comparison group (M=38.4, SD±6.9), t =-2.18(df=81), p=.03. Parents in the intervention group also reported better rapport with their counselor (M=42.5, SD±5.1), than did parents in the comparison group (M=39.7, SD±6.6), t = -2.19(df=81), p=.03. No differences were found between parents in the intervention group and comparison group on their level of session participation. Youth responses to these same measures were not significantly different between the two groups.

Discussion

This study was a test of a novel approach to engaging high-risk youth and their families in family therapy. Findings suggest that augmenting home-based family therapy with creative experiential activities can significantly increase retention in treatment. This finding is especially noteworthy, as increasing retention – a pivotal element of service provision to high-risk youth and their families – is a major challenge for social work practitioners. It is common for families to forget appointments when they must go to an office. Even though agency counselors are encouraged to call their clients prior to their meeting to remind them of the session, it is common for families to forget appointments when they must go to an office. Transportation to the agency, a barrier to treatment engagement, is also not an issue with home-based services.

Families in the intervention group noted greater satisfaction with treatment and rapport with their counselor than comparison group families. These findings may indicate that the creative, even fun, methods incorporated in the experiential activities assist parents in feeling more positive about their experiences in treatment. Although youth reports did not show differences, qualitative follow up interviews with families who participated in the intervention group highlighted the value both youth and parents found from participating in these activities (Thompson, Bender, Lantry, & Flynn, 2007). Family members noted that because the activities were enjoyable, they participated more actively in sessions and felt the activities created alternative ways to express themselves rather than simply talking. This active participation helped to increase their willingness to openly discuss difficult topics. The positive nature of the activities create a constructive environment that elicits affirming interactions among family members and overcomes strained, discordant family interactions (Thompson et al., 2007).

Limitations

Various methodological limitations should be considered in interpreting these results. The study design did not control for the influence of service setting when testing the effects of experiential engagement activities on retention. Clients in the control group received services at the agency while clients in the intervention group received services in their homes. The importance of setting and its association with engagement needs further study. Furthermore, the primary focus of this study was to examine engagement rather than treatment outcomes; thus, replication with larger sample sizes should be conducted to determine whether the in-home family therapy enhanced with experiential activities significantly improves families' abilities to reach treatment goals.

One major difficulty in the current study was the lack of measures for clients who terminated before completing all 12 sessions. Once a control group family dropped out of treatment, agency counselors would notify the research team. At that point, the research team would attempt to contact these families to collect posttest information. However, some families relocated and 4 were eventually lost to the study. Finally, although a true random assignment design was attempted, it was not possible due to various constraints. However, analyses demonstrate that the experimental and control groups were comparable across key variables.

Future Research

To address the limitations above and extend this study's findings, there are several directions for future research. A large randomized clinical trial measuring the impact of Engagement Activities as a mechanism of change in family therapy, while controlling for therapy delivered in different settings and across different racial/ethnic groups, is needed. The large differences in treatment retention and greater satisfaction and rapport among the intervention participants support the need for a larger, more controlled, and sufficiently powered study of engagement as a mechanism of change in family therapy.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported in part by a Career Development Award (K01-DA015671) from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) to Dr. Thompson. The interpretations and conclusions, however, do not necessarily represent the position of the NIDA, NIH, or the Department of Health and Human Services. The authors wish to thank the families who participated in this research.

Contributor Information

Sanna J. Thompson, University of Texas at Austin, School of Social Work, 1717 W. 6th Street Suite 295, Austin, TX 78703.

Kimberly Bender, University of Denver, Graduate School of Social Work, 2148 Sough High Street, Denver, CO 80208.

Liliane C. Windsor, Rutgers University, School of Social Work, 536 George St., New Brunswick, NJ 08901.

Patrick M. Flynn, Institute of Behavioral Research, Texas Christian University, TCU Box 298740, Fort Worth, TX 76129.

References

- Berg IK, DeJong P. Solution-building conversations: Co-constructing a sense of competence with clients. Families in Society: Journal of Contemporary Human Services. 1996;77:376–391. [Google Scholar]

- Broome KM, Joe GW, Simpson DD. Engagement Models for Adolescents in DATOS-A. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2001;16(6):608–610. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M. Therapeutic games and guided imagery. Chicago: Lyceum Books, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Santisteban DA, McBride CK, Szapocznik J. Brief strategic family therapy versus community control: Engagement, retention, and an exploration of the moderating role of adolescent symptom severity. Family Process. 2001;40(3):313–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4030100313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakof GA, Tejeda M, Liddle HA. Predictors of engagement in adolescent drug abuse treatment. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(3):274–281. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing RL, Barrick C, Dermen KH, Walitzer KS. Indicators of Client Engagement : Influences on Alcohol Treatment Satisfaction and Outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(1):71–78. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil E, Sobol B. Engaging families in therapeutic play. In: Bailey CE, editor. Children in Therapy: Using the family as a resource. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Bourduin CM, Melton GB, Mann BJ, Smith L, Hall JA. Effects of multisystemic therapy on drug use and abuse in serious juvenile offenders: A progress report from two outcome studies. Family Dynamics Addiction Quarterly. 1991;1(3):40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Joanning H, Quinn TF, Mullen R. Treating adolescent drug abuse: A comparison of family systems therapy, group therapy, and family drug education. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1992;18:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Broome KM, Rowan-Szal GA, Simpson DD. Measuring patient attributes and engagement in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4):183–196. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Simpson DD, Broome KM. Effects of readiness for drug abuse treatment on client retention and assessment of process. Addiction. 1998;93(8):1177–1190. doi: 10.1080/09652149835008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Nock MK. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Discipline. 2003;44(8):1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Wassell G. Barriers to treatment participation and therapeutic change among children referred for conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28(2):160–172. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS. Examining the effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy: A meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice. 2008;18(2):107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lay B, Blanz B, Schmidt MH. Effectiveness of home treatment in children and adolescents with externalizing psychiatric disorders. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;10(Suppl 1):80–90. doi: 10.1007/s007870170009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA. Conceptual and clinical dimensions of multidimensional, multisystems engagement strategy in family-based adolescent treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1995;32(1):39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Parker K, Diamond GS, Barrett K, Tejeda M. Multidimensional family therapy for adolescent drug abuse: Results of a randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27(4):651–688. doi: 10.1081/ada-100107661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Rowan-Szal G, Greener J. Client engagement and change during drug abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1995;7(1):117–134. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesnick N, Prestopnick JL. Office versus home-based family therapy for runaway, alcohol abusing adolescents: Examination of factors associated with treatment attendance. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2004;22(2):3–19. doi: 10.1300/J020v22n02_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton MD, Shadish WR. Outcome, attrition, and family-couples treatment for drug abuse: A meta-analysis and review of the controlled, comparative studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122(2):170–191. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Perez-Vidal A, Brickman AL, Foote FH, et al. Engaging adolescent drug abusers and their families in treatment: A strategic structural systems approach. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(4):552–557. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SJ, Bender K, Lantry J, Flynn P. Treatment engagement: Building therapeutic alliance in family-based treatment. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2007;29(12):39–55. doi: 10.1007/s10591-007-9030-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]