Abstract

Adipokines may represent a mechanism linking insulin resistance to cardiovascular disease. We showed previously that homocysteine (Hcy), an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, can induce the expression and secretion of resistin, a novel adipokine, in vivo and in vitro. Since vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) migration is a key event in vascular disease, we hypothesized that adipocyte-derived resistin is involved in Hcy-induced VSMC migration. To confirm our hypothesis, Sprague-Dawley rat aortic SMCs were cocultured with Hcy-stimulated primary rat epididymal adipocytes or treated directly with increasing concentrations of resistin for up to 24 h. Migration of VSMCs was investigated. Cytoskeletal structure and cytoskeleton-related proteins were also detected. The results showed that Hcy (300–500 μM) increased migration significantly in VSMCs cocultured with adipocytes but not in VSMC cultured alone. Resistin alone also significantly increased VSMC migration in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. Resistin small interfering RNA (siRNA) significantly attenuated VSMC migration in the coculture system, which indicated that adipocyte-derived resistin mediates Hcy-induced VSMC migration. On cell spreading assay, resistin induced the formation of focal adhesions near the plasma membrane, which suggests cytoskeletal rearrangement via an α5β1-integrin-focal adhesion kinase/paxillin-Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) pathway. Our data demonstrate that Hcy promotes VSMC migration through a paracrine or endocrine effect of adipocyte-derived resistin, which provides further evidence of the adipose-vascular interaction in metabolic disorders. The migratory action exerted by resistin on VSMCs may account in part for the increased incidence of restenosis in diabetic patients.

Keywords: adipose-vascular interaction, insulin resistance, cytoskeleton

the traditional view of adipose tissue as a passive reservoir for energy storage is no longer valid. As a novel endocrine organ, adipose tissue is now known to express and secrete various bioactive peptides known as adipokines, which act at both the local (autocrine/paracrine) and systemic (endocrine) levels. Adipokines could be important for the development of obesity-related diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer (40). Features of adipose deposits that may confer increased cardiovascular risk include leukocyte infiltration and evidence of increased adipose macrophage activity (44, 45). Adipocyte-endothelium cross talk has been suggested as an important mechanism of cardiovascular disease in metabolic syndrome (42). However, whether adipokines derived from adipose tissue are mediators of increased vascular risk is still unclear.

Homocysteine (Hcy) is a sulfur-containing amino acid formed during the metabolism of methionine. Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) has been implicated as an independent risk factor for vascular disease (21, 24, 25) and insulin resistance (18, 22). Insulin resistance has been strongly associated with atherosclerosis and frequently coexists with common proatherogenic disorders such as neointimal hyperplasia. Therefore, common mechanisms may exist between HHcy-induced vascular disease and insulin resistance. Compelling evidence has suggested the involvement of secretion of proinflammatory factors in human monocytes in HHcy-elicited atherosclerosis (8, 48).

We recently reported (18) that Hcy is highly accumulated in adipose tissue and can induce the expression and secretion of resistin, a novel adipokine, in vivo and in vitro and subsequently promote insulin resistance. Resistin is a well-characterized adipokine and positively related to insulin resistance (39). Moreover, resistin is predictive of coronary atherosclerosis in humans (34). Verma et al. (42) found that resistin activates human endothelial cells by promoting endothelin-1 release in vitro. Burnett et al. (2) further strengthened the concept that resistin is an effector molecule that mechanistically links the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, possibly through an inflammatory mechanism. Resistin promotes vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation through the ERK1/2-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway (3), which can be enhanced by hypoxia (13). Migration of VSMCs from the tunica media to the intima is crucial for neointima formation in atherosclerosis and postangioplasty restenosis (47), with high incidence in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, whether the novel adipokine resistin participates in the migratory response of VSMCs, especially under HHcy, has not been addressed.

In the present study, we hypothesized that adipocyte-derived resistin induced by Hcy is involved in VSMC migration during insulin resistance. We investigated whether resistin directly promotes VSMC migration in HHcy and, if so, the molecular pathways involved. We demonstrated for the first time that Hcy induces VSMC migration through an endocrine or paracrine effect of adipokine resistin via an α5β1-integrin-focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/paxillin-Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) pathway. Our data provide further evidence of adipose-vascular interaction in metabolic disorders. Resistin-induced migration of VSMCs may account in part for the increased incidence of restenosis in diabetes patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Recombinant resistin was purchased from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Belmont, CA). Hcy, Hoechst 33254, and mouse-anti-α-actin and rabbit-anti-phospho-FAK (Tyr397) antibodies were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Rabbit anti-phospho-paxillin (Tyr118) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Hamster anti-active α5β1-integrin antibody (HMa5–1), rabbit anti-phospho-FAK (Tyr576/577), and rabbit anti-β-actin antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit anti-resistin was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Rhodamine phalloidin was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Rabbit anti-paxillin antibody was purchased from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA). NSC23766 was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). IRDye-conjugated affinity purified anti-rabbit, -mouse, and -goat IgGs were purchased from Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA). PE mouse-anti-hamster secondary antibody was purchased from BD Pharmingen (Mississauga, ON, Canada). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from GIBCO BRL (Rockville, MD).

Cell culture.

Rat aortic VSMCs were isolated from the thoracic aortas of 3- to 4-wk-old male Sprague-Dawley rats. Isolated VSMCs were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 25 mmol/l HEPES (pH 7.4) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. VSMCs were identified by the characteristic “hill-and-valley” growth pattern and positive immunocytochemical staining with a monoclonal antibody against smooth muscle α-actin. VSMCs at passages 4–8 were used in the experiments.

Mature adipocytes were isolated from epididymal fat pads of Sprague-Dawley rats (160–200 g) as previously described (18). Packed adipocytes were diluted in serum-free DMEM to generate a 10% (vol/vol) cell suspension. For the coculture system, isolated mature adipocytes in 10% (vol/vol) cell suspension were added into the plate with VSMCs.

The investigation conformed with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Pub. No. 85-23, revised 1996) and was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Peking University.

Resistin small interfering RNA transfection.

Resistin small interfering RNA (siRNA) was designed with Block-iT RNAi Designer and chemically modified by the manufacturer (Stealth siRNAs, Invitrogen). Sequences corresponding to the siRNA of resistin were siRes335: sense 5′-GGACGUCCGUGAGGAUACAAUGUGU-3′ and antisense 5′-ACACAUUGUAUCCUCACGGACGUCC -3′ and siRes572: sense 5′-UGGUGGUGAUAAAGAUGCACGGUAA-3′ and antisense 5′-UUACCGUGCAUCUUUAUCACCACCA-3′. Transfection of rat adipocytes with the siRNA (100 nmol/l) in vitro was performed with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A scrambled Stealth RNAi duplex (catalog no. 12935, Invitrogen) served as a negative control.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

Total RNA from primary cultured rat epididymal adipocytes was isolated with TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed with a reverse transcription system from Promega (Madison, WI). One microliter of the reaction mixture was subjected to PCR. The amount of PCR products formed in each cycle was evaluated on the basis of SYBR Green I fluorescence. The specific primers for rat resistin were sense: 5′- CTACATTGCTGGTCAGTCTCC-3′ and antisense: 5′- GCTGTCCAGTCTATGCTTCC-3′, and the primers for rat β-actin were sense: 5′-GAGACCTTCAACACCCCAGCC-3′ and antisense: 5′-TCGGGGCATCGGAACCGCTCA-3′. All amplification reactions involved use of the Mx3000 Multiplex Quantitative PCR System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 min and then 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Melting curve analysis was from 55°C to 95°C at 0.2°C/s with Optics Ch1 On. The mRNA expression was quantified by use of the comparative cross threshold (CT) method with Stratagene Mx3000 software. PCR reactions were performed in duplicate, and each experiment was repeated three to five times.

Western blot analysis.

Proteins were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membrane was incubated successively with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-Tween-buffered saline at room temperature for 1 h with primary antibodies at 4°C for 12 h and then with IRDye-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. A specific immunofluorescence band was detected by the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Immunofluorescent staining.

After treatment, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, and then treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. After washing, cells were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 30 min. Next, cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, washed with PBS, and then incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h in the dark. For F-actin staining, cells were incubated with rhodamine phalloidin for 30 min. The nuclei were visualized by staining with Hoechst 33254 for 2 min. Cells were mounted with 90% glycerol-PBS and examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Leica).

VSMC migration assays.

Migration assays were performed by two approaches: scratch wound assay and modified Boyden chamber assay. For the scratch wound assay, VSMCs were cultured until they reached confluence. An area of cells was removed with a sterile pipette tip and then incubated at 37°C for the indicated times. The furthest distance that cells migrated from the wound edge was measured, and relative wound closure was calculated (average of 5 independent microscope fields for each independent experiment).

Modified Boyden chamber cell migration assay was performed in chemotaxis chambers (Neuroprobe, Pleasanton, CA). Briefly, VSMCs were suspended in DMEM-0.5% FBS to a concentration of 4 × 105/ml. Fifty microliters of suspension with VSMCs was placed in the upper chamber, and 27 μl of DMEM-5% FBS was placed in the lower chamber. Resistin at different concentrations was added. After incubation, the cells on the upper surface were removed and the cells on the underside were fixed and stained. The mean number of cells was counted from five randomly chosen fields under light microscopy in three independent experiments.

Cell spreading assay.

VSMCs resuspended in DMEM containing 0.5% FBS were replated on a special dish for confocal microscopy. Subsequently, the cells were allowed to spread for the indicated interval at 37°C. The dish was then washed with cold PBS to discard unattached cells.

Assay of α5β1-integrin activity.

After treatment, cells were washed with PBS and then incubated for 1 h on ice with anti-active α5β1-integrin antibody HMa5–1. Cells were washed three times and then incubated with PE mouse anti-hamster secondary antibodies for 1 h in the dark. Fluorescence intensity was detected by flow cytometry (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA).

Rac1 activity assay.

After treatment, cells were harvested and lysates were made with the Rac1 Activation Assay Kit (Upstate Technologies, Lake Placid, NY). Briefly, cells were lysed in magnesium lysis buffer (MLB). Cell lysates were precleared for 10 min with glutathione S-transferase (GST) beads. Lysates were then incubated with p21-activated kinase-1 (PAK-1) p21-binding domain (PBD)-agarose for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were washed three times in MLB, and samples were prepared for electrophoresis by adding 2× SDS loading dye and resolved by 15% SDS-PAGE. Guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP)-bound Rac1 was identified by use of anti-Rac1 antibody.

Migration of VSMCs out of rat aortic explants.

Rat thoracic aortas were thoroughly dissected from connective tissue and cut open longitudinally, and the intima and a thin portion of the subjacent media were removed. Rat thoracic aortas were weighed and trimmed to normalize the weight to 30 mg. The aorta was cut into 20 pieces, and each piece was placed in a chambered slide with the endothelium facing down and cultured in DMEM containing 0.5% (vol/vol) FBS. Medium was replaced every day for 5 days before analysis of the explants by light microscopy. To count cells that migrated out of the explant, the remaining tissue was removed and cells that had migrated away from the explant were detached with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA and counted under a microscope.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Data analysis involved use of GraphPad Prism software. One-way ANOVA, Student-Newman-Keuls test (comparisons between multiple groups), or unpaired Student's t-test (between 2 groups) was used as appropriate. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Adipocyte-derived factor(s) mediates Hcy-induced VSMC migration.

We first investigated whether adipocyte-derived factors facilitated VSMC migration with an adipocyte-VSMC coculture system under Hcy stimulation. In vitro scratch wound assay revealed that with Hcy stimulation (500 μM) VSMC migration was significantly enhanced; migration ability, as measured by wound closure, was significantly increased 3.2-fold in the coculture group but not altered in the control group. Smooth muscle α-actin staining excluded the contamination of fibroblasts or other adipose-derived stroma cells other than VSMCs (Fig. 1A). Control and coculture groups showed no difference in cell number. Migration ability of VSMCs cocultured with adipocytes was significantly increased by Hcy stimulation in a time-dependent manner as early as 12 h and remained increased up to 24 h (Fig. 1C) and in a concentration-dependent manner with maximal effect at 500 μM (Fig. 1D). To validate our in vitro data, we investigated whether Hcy serves as a directional cue for VSMCs within a vessel fragment cocultured with adipocytes by counting the ability of VSMCs to migrate out of aortic explants cocultured with adipocytes with or without Hcy treatment. The number of cells migrating out with Hcy stimulation (500 μM) was significantly increased in the coculture group but not in the control group (Fig. 1B). To eliminate the direct effect of adipocytes, primary cultured rat epididymal adipocytes or Cos-7 cells were treated with Hcy (500 μM) for 24 h. The conditioned medium was then collected and transferred to the primary cultured rat VSMCs. As shown in Fig. 1E, VSMCs treated with the conditioned medium from Hcy-treated adipocytes showed significantly increased migration ability in a time-dependent manner. Thus adipocyte-derived factor(s) induced by Hcy facilitated VSMC migration through a paracrine or an endocrine pathway.

Fig. 1.

Adipocyte-derived factor(s) mediates homocysteine (Hcy)-induced vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) migration. A: scratch wound assay of migration of VSMCs cocultured with adipocytes under Hcy (500 μM) stimulation; magnification ×100. Dotted lines show scratch wound margin at 0 h. B: migration of VSMCs out of rat aortic explants. Count of cells growing out from aortic explants obtained from Sprague-Dawley rats and cocultured with adipocytes with or without Hcy (500 μM) treatment is shown. C: time-dependent effect of Hcy (500 μM) stimulation on migration of VSMCs cocultured with adipocytes. D: concentration-response effect of Hcy stimulation on migration of VSMCs cocultured with adipocytes. E: endocrine or paracrine effect of Hcy stimulation on VSMC migration. Primary rat adipocytes (Adipo) or Cos-7 cells were pretreated with or without Hcy (500 μM) for 24 h; conditioned medium was then transferred to VSMCs. Data are means ± SE from 4 separate experiments. Significant difference from control: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Resistin participates in Hcy-induced migration of VSMCs cocultured with adipocytes.

We showed previously (18) that Hcy can induce the expression and secretion of resistin, a novel adipokine, from adipocytes. Since Hcy stimulated migration ability in VSMCs cocultured with adipocytes, we wondered whether resistin could affect VSMC migration directly. Scratch wound assay revealed that resistin induced VSMC migration in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2, A and B). Migration was induced by 100 ng/ml resistin as early as 6 h and remained increased up to 24 h (Fig. 2A). Resistin treatment (10–100 ng/ml) for 24 h caused a concentration-dependent increase in migration ability in primary cultured rat VSMCs (Fig. 2B). To confirm these results, we used the classic method for assessment of cell migration, a modified Boyden chamber assay. As shown in Fig. 2C, the number of migrated VSMCs was significantly increased when cells were treated with increasing concentrations of resistin (10–100 ng/ml), beginning at a concentration as low as 10 ng/ml, with maximal induction at 100 ng/ml. Thus the adipokine resistin promoted VSMC migration directly.

Fig. 2.

Resistin participates in Hcy-induced migration of VSMCs cocultured with adipocytes. A: time-dependent effect of resistin treatment (100 ng/ml) on VSMC migration. B: concentration-response effect of resistin treatment on VSMC migration. C: effect of resistin treatment on VSMC migration by modified Boyden chamber assay; magnification ×400. D: identification of resistin small interfering RNA (siRNA) by real-time PCR. Relative mRNA levels were normalized to that with scrambled siRNA treatment. E: resistin protein level in adipocytes treated with resistin siRNA. Bottom: summary results of resistin protein level. Relative protein levels were normalized to that with scrambled siRNA treatment. F: resistin knockdown retarded migration of VSMCs cocultured with Hcy-stimulated adipocytes. G: resistin knockdown retarded migration of VSMCs cocultured with Hcy-stimulated adipocytes out of rat aortic explants. Top: micrographs from a representative experiment; magnification ×100. Bottom: no. of cells migrating from explants. Data are means ± SE from 4 separate experiments. Significant difference from control: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

In the adipocyte-VSMC coculture system, knockdown of adipocyte resistin by specific siRNA was first verified, with knockdown efficiency of ∼60% at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 2, D and E). Scratch wound assay revealed that compared with scrambled siRNA, resistin siRNA knockdown retarded the migration of VSMCs cocultured with Hcy-stimulated adipocytes (Fig. 2F). To validate our in vitro data, ex vivo experiments were also performed. Compared with scrambled siRNA, resistin siRNA knockdown in adipocytes retarded by ∼50% the ability of VSMCs cocultured with Hcy-stimulated adipocytes to migrate out of rat aortic explants (Fig. 2G). These results suggest that resistin participates in Hcy-induced migration of VSMCs cocultured with adipocytes.

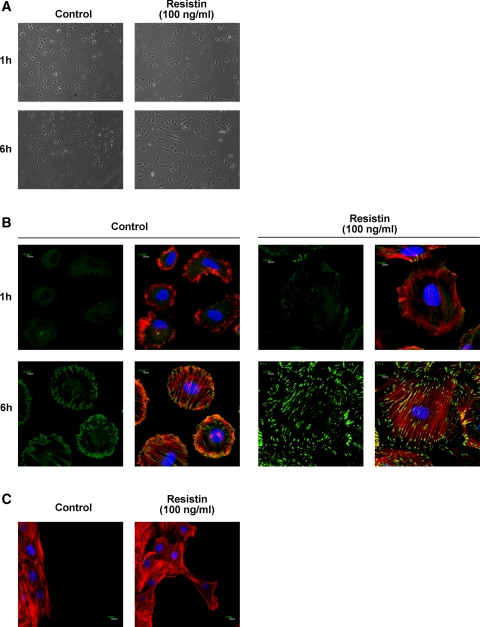

Resistin induces cytoskeletal rearrangement and formation of focal adhesion assemblies in VSMCs.

Because dynamic regulation of focal adhesion and reorganization of the associated actin cytoskeleton are crucial determinants of cell migration (11), we next investigated whether resistin had any influence on cytoskeletal rearrangement in VSMCs. VSMCs were digested and applied to spreading assays incubated with 100 ng/ml resistin. Compared with control cells, resistin-stimulated VSMCs significantly spread 6 h after seeding, as seen on light microscopy (Fig. 3A). Examination of immunofluorescence staining by confocal microscopy showed actin fibers of VSMCs pretreated with resistin (100 ng/ml) rearranged in the cytoplasm and assembled into parallel and elongated stress fibers 6 h after seeding but actin fibers of control VSMCs mainly distributed on the edge of cells (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, examination of the leading edge of the migrating cells by actin fiber staining revealed multiple protrusions and extensions in resistin-treated cells, which were vertical with the scratch wound and indicated the direction of VSMC migration (Fig. 3C). Recruitment of actin fibers to the cell membrane and stabilization of stress fibers are achieved via focal adhesion components, and immunolocalization of paxillin can be used to identify mature focal adhesion. As shown in Fig. 3B, double staining for paxillin and F-actin showed the assembly of actin cytoskeleton into parallel stress fibers and increased paxillin localization at the tips of the cells along with actin fibers in VSMCs pretreated with resistin (100 ng/ml) for 6 h. These results indicate that resistin induces cytoskeletal rearrangement and formation of focal adhesion assemblies in VSMCs.

Fig. 3.

Resistin induces cytoskeletal rearrangement and formation of focal adhesion assemblies in VSMCs. A: resistin treatment (100 ng/ml) stimulated VSMC spreading as measured by light microscopy; magnification ×100. B: double staining for paxillin and F-actin revealed the formation of focal adhesion assemblies in VSMCs treated with resistin, Photographs were taken by confocal microscopy; magnification ×1,000. C: 6 h after wounding, cells at the migrating edge were stained for F-actin. Photographs were taken by confocal microscopy; magnification ×600. F-actin stained in red, paxillin stained in green, and nucleus stained in blue. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

α5β1-Integrin mediates resistin-induced VSMC migration.

Integrins are a family of transmembrane glycoproteins that mediate cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions and play a major role in the activation of signaling events in focal adhesions and the actin-based cytoskeleton. Among them, α5β1-integrin has been reported to be related to cell migration (15, 29, 46). We next detected whether α5β1-integrin was induced by resistin. Flow cytometry revealed that α5β1-integrin was activated about threefold with resistin treatment of 5 min (100 ng/ml, Fig. 4A). The neutralizing antibody of α5β1-integrin substantially inhibited resistin-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement (Fig. 4B) and retarded resistin-induced VSMC migration (Fig. 4C). However, both the mRNA and protein levels of α5β1-integrin were not affected by resistin treatment (data not shown). These results indicate that α5β1-integrin activation plays an important role in resistin-induced VSMC migration.

Fig. 4.

α5β1-Integrin is involved in resistin-induced VSMC migration. A: flow cytometry of activation of α5β1-integrin by resistin (100 ng/ml) treatment. B: blockage of resistin-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement by neutralizing antibody of α5β1-integrin (5 μg/ml). Photographs were taken on confocal microscopy; magnification ×1,000. C: inhibitory effect of neutralizing antibody of α5β1-integrin on resistin-stimulated VSMC migration. Data are means ± SE from 3 separate experiments. **P < 0.01 vs. untreated cells; ##P < 0.01 vs. resistin treatment alone.

Resistin activates cytoskeleton-related proteins.

FAK and paxillin are adaptor proteins between actin fibers and focal adhesions. Tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin plays an important role in the dynamic regulation of focal adhesions and reorganization of the associated actin cytoskeleton (5, 27). As shown in Fig. 5, A–C, resistin (100 ng/ml) significantly induced phosphorylation of FAK (Tyr397 and Tyr576/577) and paxillin (Tyr118) from 5 min until 60 min in VSMCs, but Hcy (500 μM) had no effect. Furthermore, resistin-induced FAK and paxillin activation was inhibited by pretreating cells with a neutralizing antibody of α5β1-integrin for 1 h (Fig. 5, D–F). These results strongly indicate that cytoskeleton-related proteins, such as FAK and paxillin, may act downstream of integrin to mediate resistin-induced VSMC migration.

Fig. 5.

Resistin activates cytoskeleton-related proteins. A–C: Western blot analysis of cytoskeleton-related proteins. VSMCs were treated with resistin (100 ng/ml) or Hcy (500 μM) for the indicated times. A: phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (Tyr397). B: phosphorylation of FAK (Tyr576/577). C: phosphorylation of paxillin (Tyr118). D and E: VSMCs were pretreated with neutralizing antibody of α5β1-integrin (5 μg/ml) for 1 h and then treated with resistin (100 ng/ml) for 5 min. D: phosphorylation of FAK (Tyr397). E: phosphorylation of FAK (Tyr576/577). F: phosphorylation of paxillin (Tyr118). Bottom: summary results of protein level. Relative protein levels were normalized to the levels in untreated cells. Data are means ± SE from 4 separate experiments. **P < 0.01 vs. untreated cells; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. resistin treatment alone.

Rac1 participates in resistin-induced VSMC migration.

Rac1 is a member of the Rho family of small GTP-binding proteins, which regulate assembly of actin cytoskeletal structures associated with cell motility and metastasis (12, 38). We next investigated whether Rac1 was activated during resistin-induced VSMC migration. We detected the activation states of endogenous Rac1 in VSMCs under resistin treatment and found that resistin significantly activated Rac1 in rat VSMCs as early as 5 min (Fig. 6A). This activation was inhibited by pretreating cells with a neutralizing antibody of α5β1-integrin for 1 h (Fig. 6B). To further determine whether Rac1 participated in resistin-induced VSMC migration, VSMCs were pretreated with the Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 (100 μM) for 24 h and then stimulated with resistin (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. Scratch wound assay revealed that resistin-induced VSMC migration was significantly attenuated by NSC23766 (Fig. 6D), which also significantly attenuated resistin-induced assembly of VSMC actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 6C). Thus Rac1 participates in resistin-induced VSMC migration by acting downstream of integrin.

Fig. 6.

Rac1 participates in resistin-induced VSMC migration. A: activation states of endogenous Rac1 in VSMCs with resistin treatment (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times were detected by Rac1 activity assay. B: blockage of resistin-induced Rac1 activation by neutralizing antibody of α5β1-integrin (5 μg/ml). Bottom: intensity of Rac1-GTP/Rac1 in lysates normalized to the intensity of untreated cells. C: inhibitory effect of Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 (100 μM) on resistin-stimulated cytoskeleton rearrangement. Photographs were taken by confocal microscopy; magnification ×1,000. D: inhibitory effect of Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 (100 μM) on resistin-stimulated VSMC migration. Data are means ± SE from 3 separate experiments. **P < 0.01 vs. untreated cells; ##P < 0.01 vs. resistin treatment alone.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that Hcy promotes VSMC migration at least in part through the endocrine or paracrine effect of the adipokine resistin via an α5β1-integrin-FAK/paxillin-Rac1 pathway. Since we recently reported (18) that Hcy can induce the expression and secretion of resistin from adipocytes through the reactive oxygen species-PKC-NF-κB pathway in vivo and in vitro, and subsequently promote insulin resistance, the present results provide further evidence of adipose-vascular interaction and may account for the development of HHcy-associated insulin resistance and vascular complications.

Patients with insulin resistance are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease (30), and emerging evidence points to a common origin of metabolic and cardiovascular processes (20). Adipose tissue plays an important role in the development of a systemic inflammatory state that contributes to obesity-associated insulin resistance, vasculopathy, and cardiovascular risk, because circulating mediators of inflammation participate in the mechanisms of vascular insult and atheromatous change, and many of these inflammatory proteins are secreted directly from adipocytes and adipose tissue-derived macrophages (26). Several factors linking obesity to increased cardiovascular risk have been identified. The adipocyte-specific secretory protein resistin is a particularly promising candidate in this context, although macrophages are another important source of human resistin (42). Resistin level is predictive of coronary atherosclerosis in humans (34); resistin also activates human endothelial cells by promoting endothelin-1 release (42), promotes VSMC proliferation (3), and enhances the formation of foam cells (17). In the present study, we showed that adipocytes treated with Hcy facilitated VSMC migration (Fig. 1, A and B) and resistin played an important role in this process (Fig. 2, A–C, F, G). VSMC migration is a crucial process in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and restenosis, especially in patients with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes (16). Therefore, resistin is an intensive effector molecule that links metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance to complicated vasculopathy and atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases.

Cell migration begins with stimulation of cell surface receptors and is a complex process involving receptor-mediated adhesion, membrane protrusion, and the formation of discrete cell-matrix adhesion sites linked to a reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (5, 11). In the present study, we provide direct evidence that resistin promotes VSMC adhesion and spreading (Fig. 3A), which results in cytoskeletal rearrangement and phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin (Fig. 3B, Fig. 5, A–C). Because cell migration is a coordinated process consisting of signaling and cytoskeletal rearrangement, our data suggest that resistin might enhance the interaction between extracellular matrix and actin fiber structuring during cell migration. The cytoplasmic tails of integrins are linked to actin cytoskeleton via a complex of anchoring proteins known as focal adhesion components (4), including FAK and paxillin; the association of paxillin with integrins markedly enhanced the rates of integrin-dependent phosphorylation of FAK and cell migration (19, 33). Our finding that resistin significantly enhanced levels of phosphorylated paxillin might explain the increased phosphorylation of downstream kinases such as FAK in VSMCs. It was also reported that paxillin is a substrate for FAK-Src complex (43); therefore, further investigation of the interaction between FAK and paxillin in resistin-induced VSMC migration is still needed.

VSMC migration is associated with the expression of an altered set of integrins with different functional ability. Among them, α5β1-integrin, which is highly abundant in cultured VSMCs, has important implications for VSMC signaling (29). α5β1-Integrin could be a receptor mediating VSMC behaviors to cause vessel narrowing during the progression of atherosclerosis (46), especially through stimulating VSMC migration, since α5β1-integrin, together with αvβ3-integrin, has been shown to be responsible for VSMC migration into fibrin gels (15). In the present study, we showed that although α5β1-integrin mRNA and protein levels were not affected, α5β1-integrin was significantly activated under resistin treatment (Fig. 4A) and the neutralizing antibody of α5β1-integrin significantly inhibited resistin-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement (Fig. 4B) and retarded resistin-induced VSMC migration (Fig. 4C), which indicates that α5β1-integrin plays an important role in resistin-induced VSMC migration. Integrins can assume various affinity states that can be regulated by bidirectional signaling (14, 32), either by “outside-in” signaling induced by extracellular factors or “inside-out” signaling, whereby intracellular events lead to extracellular conformational changes that determine the affinity for ligands and integrin on the cell surface (7, 37). αvβ3-Integrin, expressed in smooth muscle cells, modulates insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) actions in stimulating cell migration and division through interaction with IGF-I receptor (6). The receptor for resistin is still unknown. As a peptide hormone, resistin might exert its effect on VSMC migration through the interaction of its receptor with α5β1-integrin. Further investigation is needed to clarify how resistin affects integrin affinity.

Rho family GTPases (Rho, Rac, and Cdc42) have distinct functions in regulating the actin-based cytoskeletal structure (41). Among them, Rac1 induces lamellipodia formation and membrane ruffles, as well as wavy, loose bundles of actin filaments in the periphery (35, 38). Activation of Rac1 has been observed during VSMC migration stimulated by platelet-derived growth factor (9). In the present study, Rac1 activity was significantly induced by resistin treatment (Fig. 6A); inhibition of Rac1 activity attenuated resistin-induced cytoskeletal rearrangement (Fig. 6C) and migratory activity of VSMCs (Fig. 6D), which indicates the important role of Rac1 in resistin-induced VSMC migration. Recent studies have suggested that integrins can activate Rac (31), and overexpression of β1-integrin increased Rac1 activity and lamellipodia formation (23). Inhibition of α5β1-integrin activity impaired Rac1 activity (Fig. 6B), which revealed that Rac1 is the downstream signal of α5β1-integrin in resistin-induced VSMC migration.

HHcy is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis. HHcy likely contributes in part to enhance vascular inflammation and atherogenic damage by promoting monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) secretion via oxidation stress and NF-κB activation (8, 48), impairing endothelial function (10), inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress (28), and modulating the metabolism of cholesterol (36). However, the precise mechanism is still elusive. It was reported that Hcy alone could stimulate VSMC migration directly in a p38-dependent pathway only at large doses (1–2 mM) (1). In the present study, we showed that a lower dose of Hcy (300–500 μM) promotes VSMC migration through the endocrine or paracrine effect of the adipokine resistin via an α5β1-integrin-FAK/paxillin-Rac1 pathway, which could not be regulated by angiotensin II, the peptide which is well known to modulate VSMC migration and be elevated in diabetes. Our results provide a novel insight into and a new signaling pathway for the mechanism of adipose-vascular interaction in HHcy-facilitated vascular complications.

In conclusion, our present results demonstrate that Hcy promotes VSMC migration through an endocrine or a paracrine effect of adipokine resistin, which provides further evidence of adipose-vascular interaction in metabolic disorders. The migratory action exerted by resistin on VSMCs may account in part for the increased incidence of restenosis and atherosclerosis in diabetes patients.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Major National Basic Research Program of the People's Republic of China (no. 2006CB503802), a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 30730042, 30821001), and the Key Grant Project of Chinese Ministry of Education (no. 307001) to X. Wang; the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 30700376, 30971085), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (no. 7083110), the Scientific Research Foundation for Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry to Y. Li; and the Chang Jiang Scholars Program to Q. Xu.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest exist.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Xinhua Liu from Peking University Health Science Center for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akasaka K, Akasaka N, Di Luozzo G, Sasajima T, Sumpio BE. Homocysteine promotes p38-dependent chemotaxis in bovine aortic smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Surg 41: 517– 522, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnett MS, Lee CW, Kinnaird TD, Stabile E, Durrani S, Dullum MK, Devaney JM, Fishman C, Stamou S, Canos D, Zbinden S, Clavijo LC, Jang GJ, Andrews JA, Zhu J, Epstein SE. The potential role of resistin in atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis 182: 241– 248, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calabro P, Samudio I, Willerson JT, Yeh ET. Resistin promotes smooth muscle cell proliferation through activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways. Circulation 110: 3335– 3340, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carragher NO, Frame MC. Focal adhesion and actin dynamics: a place where kinases and proteases meet to promote invasion. Trends Cell Biol 14: 241– 249, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark EA, Brugge JS. Integrins and signal transduction pathways: the road taken. Science 268: 233– 239, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemmons DR, Maile LA. Interaction between insulin-like growth factor-I receptor and alphaVbeta3 integrin linked signaling pathways: cellular responses to changes in multiple signaling inputs. Mol Endocrinol 19: 1– 11, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cluzel C, Saltel F, Lussi J, Paulhe F, Imhof BA, Wehrle-Haller B. The mechanisms and dynamics of alphavbeta3 integrin clustering in living cells. J Cell Biol 171: 383– 392, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai J, Li W, Chang L, Zhang Z, Tang C, Wang N, Zhu Y, Wang X. Role of redox factor-1 in hyperhomocysteinemia-accelerated atherosclerosis. Free Radic Biol Med 41: 1566– 1577, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doanes AM, Irani K, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Finkel T. A requirement for rac1 in the PDGF-stimulated migration of fibroblasts and vascular smooth cells. Biochem Mol Biol Int 45: 279– 287, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eberhardt RT, Forgione MA, Cap A, Leopold JA, Rudd MA, Trolliet M, Heydrick S, Stark R, Klings ES, Moldovan NI, Yaghoubi M, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Farber HW, Cohen R, Loscalzo J. Endothelial dysfunction in a murine model of mild hyperhomocyst(e)inemia. J Clin Invest 106: 483– 491, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerthoffer WT. Mechanisms of vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circ Res 100: 607– 621, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gopalakrishnan S, Dunn KW, Marrs JA. Rac1, but not RhoA, signaling protects epithelial adherens junction assembly during ATP depletion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C261– C272, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hung HF, Wang BW, Chang H, Shyu KG. The molecular regulation of resistin expression in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells under hypoxia. J Hypertens 26: 2349– 2360, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110: 673– 687, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikari Y, Yee KO, Schwartz SM. Role of alpha5beta1 and alphavbeta3 integrins on smooth muscle cell spreading and migration in fibrin gels. Thromb Haemost 84: 701– 705, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kornowski R, Mintz GS, Kent KM, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Bucher TA, Hong MK, Popma JJ, Leon MB. Increased restenosis in diabetes mellitus after coronary interventions is due to exaggerated intimal hyperplasia. A serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation 95: 1366– 1369, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee TS, Lin CY, Tsai JY, Wu YL, Su KH, Lu KY, Hsiao SH, Pan CC, Kou YR, Hsu YP, Ho LT. Resistin increases lipid accumulation by affecting class A scavenger receptor, CD36 and ATP-binding cassette transporter-A1 in macrophages. Life Sci 84: 97– 104, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Jiang C, Xu G, Wang N, Zhu Y, Tang C, Wang X. Homocysteine upregulates resistin production from adipocytes in vivo and in vitro. Diabetes 57: 817– 827, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Thomas SM, Woodside DG, Rose DM, Kiosses WB, Pfaff M, Ginsberg MH. Binding of paxillin to alpha4 integrins modifies integrin-dependent biological responses. Nature 402: 676– 681, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mather K, Anderson TJ, Verma S. Insulin action in the vasculature: physiology and pathophysiology. J Vasc Res 38: 415– 422, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCully KS. Homocysteine and vascular disease. Nat Med 2: 386– 389, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meigs JB, Jacques PF, Selhub J, Singer DE, Nathan DM, Rifai N, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Wilson PW. Fasting plasma homocysteine levels in the insulin resistance syndrome: the Framingham offspring study. Diabetes Care 24: 1403– 1410, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miao H, Li S, Hu YL, Yuan S, Zhao Y, Chen BP, Puzon-McLaughlin W, Tarui T, Shyy JY, Takada Y, Usami S, Chien S. Differential regulation of Rho GTPases by beta1 and beta3 integrins: the role of an extracellular domain of integrin in intracellular signaling. J Cell Sci 115: 2199– 2206, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moshal KS, Sen U, Tyagi N, Henderson B, Steed M, Ovechkin AV, Tyagi SC. Regulation of homocysteine-induced MMP-9 by ERK1/2 pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C883– C891, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mujumdar VS, Tummalapalli CM, Aru GM, Tyagi SC. Mechanism of constrictive vascular remodeling by homocysteine: role of PPAR. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 282: C1009– C1015, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohman MK, Shen Y, Obimba CI, Wright AP, Warnock M, Lawrence DA, Eitzman DT. Visceral adipose tissue inflammation accelerates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation 117: 798– 805, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Opazo Saez A, Zhang W, Wu Y, Turner CE, Tang DD, Gunst SJ. Tension development during contractile stimulation of smooth muscle requires recruitment of paxillin and vinculin to the membrane. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C433– C447, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Outinen PA, Sood SK, Pfeifer SI, Pamidi S, Podor TJ, Li J, Weitz JI, Austin RC. Homocysteine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and growth arrest leads to specific changes in gene expression in human vascular endothelial cells. Blood 94: 959– 967, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickering JG, Chow LH, Li S, Rogers KA, Rocnik EF, Zhong R, Chan BM. Alpha5beta1 integrin expression and luminal edge fibronectin matrix assembly by smooth muscle cells after arterial injury. Am J Pathol 156: 453– 465, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plutzky J, Viberti G, Haffner S. Atherosclerosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance: mechanistic links and therapeutic targets. J Diabetes Complications 16: 401– 415, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price LS, Leng J, Schwartz MA, Bokoch GM. Activation of Rac and Cdc42 by integrins mediates cell spreading. Mol Biol Cell 9: 1863– 1871, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qin J, Vinogradova O, Plow EF. Integrin bidirectional signaling: a molecular view. PLoS Biol 2: e169, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramprasad OG, Srinivas G, Rao KS, Joshi P, Thiery JP, Dufour S, Pande G. Changes in cholesterol levels in the plasma membrane modulate cell signaling and regulate cell adhesion and migration on fibronectin. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 64: 199– 216, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reilly MP, Lehrke M, Wolfe ML, Rohatgi A, Lazar MA, Rader DJ. Resistin is an inflammatory marker of atherosclerosis in humans. Circulation 111: 932– 939, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ridley AJ, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rho regulates the assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers in response to growth factors. Cell 70: 389– 399, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma M, Rai SK, Tiwari M, Chandra R. Effect of hyperhomocysteinemia on cardiovascular risk factors and initiation of atherosclerosis in Wistar rats. Eur J Pharmacol 574: 49– 60, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimaoka M, Takagi J, Springer TA. Conformational regulation of integrin structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 31: 485– 516, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Small JV, Rottner K, Kaverina I. Functional design in the actin cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol 11: 54– 60, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, Brown EJ, Banerjee RR, Wright CM, Patel HR, Ahima RS, Lazar MA. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature 409: 307– 312, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trayhurn P, Beattie JH. Physiological role of adipose tissue: white adipose tissue as an endocrine and secretory organ. Proc Nutr Soc 60: 329– 339, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Aelst L, D'Souza-Schorey C. Rho GTPases and signaling networks. Genes Dev 11: 2295– 2322, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verma S, Li SH, Wang CH, Fedak PW, Li RK, Weisel RD, Mickle DA. Resistin promotes endothelial cell activation: further evidence of adipokine-endothelial interaction. Circulation 108: 736– 740, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Webb DJ, Donais K, Whitmore LA, Thomas SM, Turner CE, Parsons JT, Horwitz AF. FAK-Src signalling through paxillin, ERK and MLCK regulates adhesion disassembly. Nat Cell Biol 6: 154– 161, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112: 1796– 1808, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu H, Ghosh S, Perrard XD, Feng L, Garcia GE, Perrard JL, Sweeney JF, Peterson LE, Chan L, Smith CW, Ballantyne CM. T-cell accumulation and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted upregulation in adipose tissue in obesity. Circulation 115: 1029– 1038, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yee KO, Rooney MM, Giachelli CM, Lord ST, Schwartz SM. Role of beta1 and beta3 integrins in human smooth muscle cell adhesion to and contraction of fibrin clots in vitro. Circ Res 83: 241– 251, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zargham R, Touyz RM, Thibault G. Alpha 8 integrin overexpression in de-differentiated vascular smooth muscle cells attenuates migratory activity and restores the characteristics of the differentiated phenotype. Atherosclerosis 195: 303– 312, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng X, Dai J, Remick DG, Wang X. Homocysteine mediated expression and secretion of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and interleukin-8 in human monocytes. Circ Res 93: 311– 320, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]