Abstract

In vitro studies of isolated skeletal muscle have shown that oxidative stress is limiting with respect to contractile function. Mitochondria are a potential source of muscle function-limiting oxidants. To test the hypothesis that skeletal muscle-specific mitochondrial oxidative stress is sufficient to limit muscle function, we bred mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by the promoter for the inhibitory subunit of troponin (TnIFast-iCre) with mice containing a floxed Sod2 (Sod2fl/fl) allele. Mn-SOD activity was reduced by 82% in glycolytic (mainly type II) muscle fiber homogenates from young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. Furthermore, Mn-SOD content was reduced by 70% only in type IIB muscle fibers. Aconitase activity was decreased by 56%, which suggests an increase in mitochondrial matrix superoxide. Mitochondrial superoxide release was elevated more than twofold by mitochondria isolated from glycolytic skeletal muscle in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. In contrast, the rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production was reduced by 33%, and only during respiration with complex II substrate. F2-isoprostanes were increased by 36% in tibialis anterior muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. Elevated glycolytic muscle-specific mitochondrial oxidative stress and damage in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice were associated with a decreased ability of the extensor digitorum longus and gastrocnemius muscles to produce contractile force as a function of time, whereas force production by the soleus muscle was unaffected. TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice ran 55% less distance on a treadmill than wild-type mice. Collectively, these data suggest that elevated mitochondrial oxidative stress and damage in glycolytic muscle fibers are sufficient to reduce contractile muscle function and aerobic exercise capacity.

Keywords: muscle function, contractile function, oxidative damage, free radical

skeletal muscle fatigue has been defined as the decline in muscle performance associated with muscle activity (1). An association between oxidative stress and skeletal muscle fatigue was first shown by Davies et al. (10), who measured a twofold increase in carbon-centered free radicals following exercise in rats. This finding was confirmed in rats and subsequently verified in mice and humans (25) by identification of a 70% increase in muscle free radical content following contractile activity. Increases in free radical content following muscle contractile activity are also associated with increased oxidative damage to lipid (11, 12, 49), protein (29, 55), and DNA (36, 52).

Whether increased free radicals and oxidative damage are a cause or a consequence of fatiguing contractile activity has been studied using antioxidant supplementation. Intravenous injection of N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a reduced thiol donor that has general antioxidant properties (4), into anesthetized rabbits reduced diaphragm fatigue by 25% during a protocol of repetitive contractions, a finding that directly link oxidative stress to muscle fatigue (46). In addition, incubation of rat diaphragm muscle fibers with NAC in vitro has been shown to reduce fatigue, eliminating the potential role of NAC in nonmuscle targets (26). Addition of antioxidants such as Cu,Zn-SOD, catalase, and DMSO to isolated muscle fiber bundles has also been shown to reduce muscle fatigue during contractile activity (39). Cu,Zn-SOD and catalase are membrane impermeable, and reduction of fatigue in their presence indicates that extracellular oxidative stress contributes to reduced muscle function. On the other hand, NAC and DMSO are membrane permeable, which suggests that intracellular oxidative stress may limit muscle function. Incubation of skeletal muscle with the membrane-permeable oxidant H2O2 has also been shown to reduce muscle function (3), further supporting the role of intracellular oxidants in limiting muscle function. The direct role of intracellularly derived oxidants in contractile activity-induced fatigue was identified by Moopanar and Allen (32), who showed attenuation of fatigue in the presence of the membrane-permeable antioxidant Tiron. Tiron acts as a scavenger of superoxide radicals (20). Collectively, these data indicate that extra- and intracellularly derived oxidants can alter muscle function, although the oxidant-producing source is not known.

Mitochondria are a possible source of the oxidants that limit contractile activity. A role for mitochondria-generated oxidants is supported by the observation that mitochondrial antioxidant defense was decreased (53), muscle mitochondrial oxidative stress was elevated (30, 57), and treadmill endurance capacity was reduced (28) in mice heterozygous for Sod2 (Sod2+/−). However, the tissue that is limiting with respect to oxidative stress and exercise is not known, inasmuch as all tissues in Sod2+/− mice are reduced in terms of Sod2 content. The purpose of this study was to determine whether skeletal muscle-specific mitochondrial oxidative stress is sufficient to limit muscle function.

Skeletal muscle is not homogeneous with respect to fiber type. Individual skeletal muscle fibers contain myosin heavy chain type I, IIA, IIX, or IIB (42, 43) and are different in terms of oxidative and glycolytic enzyme content. Oxidative enzymes and mitochondria are most abundant in type I muscle fibers, but glycolytic protein is less abundant in type I than in type IIA, IIB, or IIX fibers. Levels of oxidative enzymes and mitochondria are low, but abundance of glycolytic proteins is high, in type IIB muscle fibers (37). Type IIA and IIX fibers are intermediate in terms of combined oxidative and glycolytic capacity. Mitochondria from type I and type II skeletal muscle have been shown to differentially produce reactive oxygen species. Mitochondrial free radical leak was reported to be greater in white gastrocnemius (a muscle rich in type IIB fiber) than in muscles consisting mostly of type IIA (red gastrocnemius) or type I (soleus) fibers (2, 38). In support of these data, mitochondrial protein oxidative damage has been shown to be greater in muscles consisting mostly of type II fibers [tibialis anterior (TA), extensor digitorum longus (EDL), and plantaris] than in the soleus, a muscle enriched with type I muscle fibers (14). The goal of the present report was to investigate the direct role of elevated type II skeletal muscle-specific mitochondrial oxidative stress in muscle function. To address our hypothesis, we used young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice, in which Mn-SOD is reduced by 70% only in type IIB skeletal muscle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

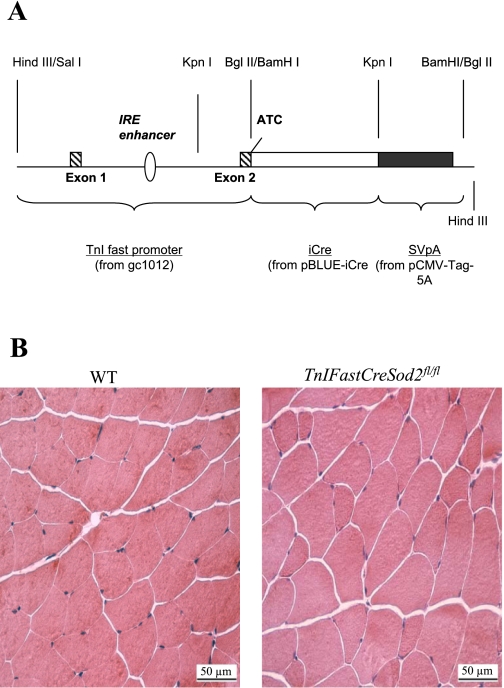

Creation of TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice.

A Cre recombinase-LoxP approach (44) was used to reduce Mn-SOD content specifically in type IIB skeletal muscle fibers. Cre activity is dependent on the activity of the promoter to which it is coupled. The promoter gC1012 [from quail, as prepared by Yutzey et al. (58)] for the inhibitory subunit of troponin (TnIFast) was used to drive Cre recombinase expression. Expression of the TnIFast promoter has been shown to be fourfold greater in type IIB than in type I, IIA, and IIX skeletal muscle fibers (21, 22). An improved version of Cre recombinase, known as iCre (45), has been shown to have greater recombinatorial efficiency in mammalian systems than the Cre as described by Schwenk et al. (44) and was used to drive Cre expression. To create the TnIFastCre construct, we discarded all DNA downstream of the TnIFast ATG initiation codon in exon 2. Upstream of exon 2, the TnIFast promoter contains 530 bp of 5-flanking DNA, exon 1, intron 1, the IRE enhancer (22) and the first (untranslated) part of exon 2 of the quail TnIFast gene. The TnIFastCre junction exists within the TnIFast ATG initiation codon. For creation of the TnIFastCre construct, TnIFast protein-coding sequences upstream of exon 2 were replaced with iCre coding sequences and linked to SV-40 splicing and polyadenylation signals (Fig. 1A). Sod2fl/fl mice (24) were then bred to mice containing TnIFastCre to produce TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl. All mice were from a C57/BL6 background. PCR was used to identify mice carrying the Cre and Flox constructs. For the Cre PCR, 5′-ACTACCTCC TGTACC TGCAAGC-3′ and 5′GGAGATGTCCTTCACTCTGATT-3′ were used as Cre-forward and Cre-reverse primers, respectively. A band at 350 bp is indicative of the presence of the Cre construct. For the Flox PCR, three primers were used: Flox P1 (5′-CGAGGGGCATCTAGT GGAGAAG-3′), Flox P2 (5′-TTAGGGCTCAGGTTTGTCCAGAA-3′), and Flox P4 (5′-AGC TTGGCTGGACGTAA-3′) (24). An fl/fl mouse was identified by the presence of a single band at 358 bp. Mn-SOD activity assays on glycolytic (white gastrocnemius and quadriceps) and oxidative (soleus) muscle homogenates were performed according to the method of Beauchamp and Fridovich (5) after PCR identification of mice containing the Cre and Sod2fl/fl constructs (TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl). All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free barrier conditions. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the University of Michigan (for contraction studies).

Fig. 1.

A: TnIFastiCre gene construct. TnIFast promoter (from quail gC1012) coupled to the IRE enhancer and to iCre were used to drive Cre expression primarily in type IIB skeletal muscle. B: representative cross section of gastrocnemius muscle stained with hematoxylin-eosin. WT, wild-type.

Animals.

Young (5- to 8-mo-old) female TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice were used for all experiments, except assays involving the rate of mitochondrial H2O2 and F2-isoprostanes, in which young (3- to 4-mo-old) male mice were used. An animal was considered wild-type in the absence of TnIFastCre and in the presence of Sod2fl/fl.

Measurement of lean body mass and body fat percentages.

Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (qMRI) was used to determine the percentages of body fat and lean mass. qMRI measurements of body fat and lean mass provide increased precision, accuracy, speed of results, and ease of use compared with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry or chemical methods (50, 51). For quantitative magnetic resonance measurements, live mice were placed into a thin-walled plastic cylinder (4.7 cm ID, 0.15 cm thick), where they were free to turn around but were limited to ∼4-cm vertical movements by a plastic insert. The plastic cylinder containing the live mice was then placed into the qMRI machine (EchoMRI, Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX) for measurement of lean and fat mass. Measurements were completed after 2 min, and the mice were returned to their home cage (51).

Mn-SOD and Cu,Zn-SOD activity.

Mn-SOD and Cu,Zn-SOD activity in tissue homogenates of liver, heart, brain, kidney, lung, and skeletal muscle isolated from wild-type and TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice was measured using native gels, as previously described (5). White portions of gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscles were used to evaluate Mn-SOD activity in mainly glycolytic skeletal muscle. Gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscles consist almost exclusively of type IIB skeletal muscle fibers (8). Red portions of gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscles were removed to minimize type I/IIA-containing fibers. Soleus muscle was used to evaluate Mn-SOD activity in a skeletal muscle consisting exclusively of type I + IIA fibers (8). Tissue homogenates containing 25–80 μg of protein were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels and run at 150 V for 2 h. The gel was soaked in a solution containing nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT), riboflavin, and tetramethylethylenediamine. Tetramethylethylenediamine reduces riboflavin, which then reduces oxygen, thereby forming superoxide. Superoxide reduces NBT, which forms the characteristic color of a blue formazan. Regions of SOD activity will be colorless, inasmuch as SOD prevents the reduction of NBT. The gel image was recorded with a digital camera-imager system (ImageMaster VDS, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and analyzed using ImageQuant software (Sunnyvale, CA) to quantify the intensity of the regions representing Mn-SOD and Cu,Zn-SOD activity.

Mn-SOD and skeletal muscle fiber type immunofluorescence.

Gastrocnemius with attached soleus muscle from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice was removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane. Sections (6 μm) were prepared with a cryostat, air dried, and processed for histological and immunofluorescence studies. After routine hematoxylin-eosin staining, regenerated myofibers were identified by the presence of centrally located myofiber nuclei. For immunofluorescence, a PAP pen (Bioindustrial Products, San Antonio, TX) was used to create a hydrophobic area around the muscle sections, which were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 20 min and then washed (twice) with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. All primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 3% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100. Primary antibodies specific for skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain type IIB (BFF3, as obtained from hybridoma cell line clone BFF3) (42, 43), myosin heavy chain type I (BAD5, Sigma) (42, 43), myosin heavy chain type IIA (SC-71, as obtained from hybridoma cell line clone SC71), and Mn-SOD [a kind gift from Dr. Takuji Shirasawa (35)] were added at dilutions of 1:1,000, 1:5,000, and 1:250 (Mn-SOD was added to SC-71-containing buffer, the supernatant of the SC-71 hybridoma cell line). BFF3 was incubated in darkness at room temperature for 90 min, BAD5 was incubated in darkness for 1 h at room temperature, and the combination of SC-71 and Mn-SOD was incubated overnight at 4°C. Muscle sections were washed twice with PBS after all primary antibody incubations and secondary antibody [goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; 1:1,000 dilution), goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 680 (Invitrogen; 1:1,000 dilution), goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen; 1:500 dilution), and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 350 (Invitrogen; 1:1,000 dilution)] additions. All secondary antibodies were incubated at room temperature for 1 h in the dark. After each secondary antibody addition, sections were washed three times for 5 min each with PBS, 4% paraformaldehyde was added at 4°C for 2 min, and, finally, the sections were washed again twice for 5 min each with PBS. Prolong Gold (Invitrogen) was added to maximize fluorescence stability. Fluorescent images were captured with a microscope (Eclipse TE2000-U, Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) and analyzed using NIS-Elements software.

Measurement of aconitase activity.

Aconitase activity has been shown to be a sensitive indicator of mitochondrial matrix superoxide content (16–19). Aconitase activity was measured in homogenates of muscles consisting primarily of type II fibers (white gastrocnemius and quadriceps) and type I fibers (soleus) in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. Activity was measured in a buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris·HCl, 600 μM MnCl2, 200 μM NADP+, 30 mM citrate, and 2 U/ml isocitrate dehydrogenase plus 66–103 μg of tissue homogenate protein. The assay for the measurement of aconitase activity is a coupled reaction involving the isomerization of citrate to isocitrate (via aconitase) and isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate (via isocitrate dehydrogenase). During this process, NADP+ is reduced to NADPH. The rate at which NADP+ is reduced (measured via fluorescence, with excitation at 355 nm and emission at 460 nm) is directly proportional to aconitase activity. Activity was expressed as units of NADPH produced per minute per milligram of homogenate protein.

Isolation of skeletal muscle mitochondria.

Combined white gastrocnemius and quadriceps muscles from individual mice were isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice and resuspended (0.5 ml) in buffer A (in mM: 100 KCl, 50 MOPS, 1 EGTA, 5 MgSO4·7 H2O, and 1 ATP, pH 7.4). Skeletal muscle mitochondria were isolated according to the method of King et al. (27). Skeletal muscle was minced in buffer A at a 1:10 dilution (wet wt/vol). Mitochondria were released from the myofibrils with the addition of trypsin (10 mg/g wet wt) and neutral protease (1 mg/g wet wt) by incubation on ice for 20 min. Samples were homogenized by hand with a Potter-Elvejhem homogenizer. An equivalent volume of buffer B (buffer A + 0.2% BSA with 1 mM EGTA) was added, and the sample was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in buffer B and then homogenized. The mitochondria-rich supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 600 g. Skeletal muscle mitochondria were pelleted by centrifugation at 7,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Mitochondria were washed with 2.5 ml of buffer B and centrifuged again at 7,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant was removed, and skeletal muscle mitochondria were resuspended in 1 ml of KME (100 mM KCl, 50 mM MOPS, and 0.5 mM EGTA) and centrifuged at 7,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was discarded, and the pellet containing mitochondria was used immediately. Mitochondrial protein concentration was measured using the Bradford method.

Measurement of the rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production.

Mitochondrial H2O2 release was measured using Amplex Red (N-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR)-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (59). The assay utilizes HRP to catalyze the H2O2-dependent oxidation of the nonfluorescent compound Amplex Red to the fluorescent resorufin and detects only H2O2 that has been released from the mitochondria, inasmuch as the size of HRP prevents its entry into the mitochondria. The rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production was measured as previously described (33). Briefly, 80 μM Amplex Red reagent and 1 U/ml HRP were added to the mitochondria (40 μg protein per sample) or to the H2O2 standard solution in 100 μl of reaction buffer: 125 mM KCl, 10 mM MOPS, 5 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM K2HPO4 (pH 7.44). Glutamate + malate (2.5 mM) was used to stimulate respiration through complex I, III, and IV. Succinate (5 mM) + rotenone (0.5 μM) was added to drive respiration through complex II, III, and IV. Antimycin A (AA, 0.5 μM), an inhibitor specific for the Qi site of complex III, was added to succinate + rotenone-supported respiration to examine the maximal rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production. Cu,Zn-SOD (100 U/ml) was added to convert any O2•− present to H2O2, preventing interaction of the superoxide with the HRP directly. Fluorescence was followed at 530-nm excitation and 590-nm emission for 10 min in an automatic microplate reader (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) equipped with a thermally controlled compartment.

Measurement of mitochondrial superoxide release.

Mitochondrial superoxide release was directly measured by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) with use of the spin trap 5-diisopropoxyphosphoryl-5-methyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DIPPMPO) (9). EPR measurements were performed using an X-band MS200 spectrometer (Magnetech, Berlin, Germany) following the general outline of the methodology of Bhattacharya et al. (6). Mitochondria (20 μg) isolated from glycolytic skeletal muscle in young mice were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in buffer containing 125 mM KCl, 10 mM MOPS, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM K2HPO4, 2 mM diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid, 50 mM DIPPMPO, a 1:1,000 dilution of catalase (to eliminate potential hydroxyl radical generation from H2O2), and either complex I (glutamate + malate, 24 mM) or complex II substrate (24 mM succinate + 2.4 μM rotenone), pH 7.44. Rotenone was added to minimize reverse electron transfer through complex I while mitochondria respired on succinate. EPR measurements were begun by the addition of 40 μl of this mixture to a 50-μl capillary tube at 37°C with the following settings: 5 × 105 receiver gain, 20 mW microwave power, 9.55 GHz microwave frequency, 2 G modulation amplitude, 40 s scan time, and 100 G scan width, with an accumulation of 10 scans. The intensity of the EPR spectra corresponds to the amount of DIPPMPO bound to superoxide, inasmuch as the addition of Cu,Zn-SOD (1 U/μl) completely abolished the EPR signal. EPR data are expressed as relative intensity units per 20 μg of mitochondrial protein.

Measurement of isoprostanes.

Levels of F2-isoprostanes in TA muscles were determined as described by Ward et al. (56). Briefly, F2-isoprostanes were extracted and quantified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry using the internal standard [2H4]8-Iso-PGF2α, which was added to the samples at the beginning of extraction to correct yield of the extraction process. The amount of F2-isoprostanes in TA muscles was expressed as picograms of 8-Iso-PGF2α per milligram of total TA protein.

Skeletal muscle fatigability.

Mice were anesthetized with initial intraperitoneal injections of tribromoethanol (400 mg/kg) and supplemental injections to maintain an adequate level of anesthesia during the procedure. Gastrocnemius muscle contractile properties were measured in situ (31). In anesthetized mice, the whole gastrocnemius muscle was isolated from surrounding muscle and connective tissue, and the distal tendon was severed and secured to the lever arm of a servomotor (model 305B, Aurora Scientific). The muscle was simulated via the tibial nerve using a bipolar platinum wire electrode. Stimulation voltage (typically 5–10 V) and then muscle length were adjusted to give maximum twitch force (Po). With muscles held at optimal muscle length, trains of 0.2-ms stimulus pulses were applied at increasing frequencies until a maximum Po was reached. For the fatigue test, muscles were stimulated with 100-Hz trains of 0.5-s durations, once each 5 s for 15 min. For soleus and EDL muscles, the contraction protocol was identical to that described for gastrocnemius muscles, except measurements were made in vitro and the duration of the fatigue protocol was 5 min, rather than 15 min. For in vitro contractile properties, each muscle was removed from the animal and placed in a horizontal bath containing buffered mammalian Ringer solution (in mM: 137 NaCl, 24 NaHCO3, 11 glucose, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, and 0.025 turbocurarine chloride) maintained at 25°C and bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2 to stabilize pH at 7.4. One tendon was tied to a force transducer (model BG-50, Kulite Semiconductor Products) and the other tendon to a fixed post. Muscles were stimulated between two stainless steel plate electrodes. After all force measurements, muscles were blotted and weighed, and total fiber cross-sectional area was calculated by dividing the muscle mass by the product of fiber length (determined from previously established muscle length-to-fiber length ratios) and muscle density, 1.06 g/cm2. Specific Po (kN/m2) was calculated for each muscle by dividing Po by cross-sectional area. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (1 factor repetition) was used to identify changes in force production over time.

Treadmill endurance capacity test.

Young female mice were run on a treadmill (Exer-6, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) on a 15% incline. The first 5 min were considered exercise acclimatization, as mice were run at 7 m/min for 5 min. Mice were then run at 12 m/min for 120 min. Treadmill speed was increased to 17 m/min for 10 min if an animal reached 120 min and then increased to 22 m/min until exhaustion. Exhaustion was determined by a failure to engage the treadmill in the presence of a mild shock and by physical prodding. Exhaustion was also defined biochemically, with blood glucose <60 mg/dl or blood lactate >12 mM.

Measurement of biochemical metabolites.

The mouse tail was nicked with a scalpel, and the tail vein was massaged to obtain an appropriate volume of blood (∼5 μl) for glucose and lactate measurements. Blood glucose was measured using a OneTouch Ultra blood glucose meter (Lifescan). Blood lactate was measured using the Lactate Plus meter (Nova Biomedical). Glucose and lactate levels during exercise were measured at the indicated time points (i.e., at 0, 20, and 40 min of running and at exhaustion) with use of the glucose and lactate meters, respectively.

Western blotting.

Skeletal muscle homogenates were prepared in assay buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl buffer with 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, and 1× protease inhibitor. Equivalent amounts of protein (40–80 μg) for each sample were resolved in 4–20% Tris·HCl-SDS-polyacrylamide gels in triplicate. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was incubated in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4, with 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T) containing 10% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were reacted with mouse aconitase (1:2,000 dilution, a kind gift from Luke Szweda, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, OK) and succinate dehydrogenase complex A (1:1,000 dilution; Invitrogen) and succinate dehydrogenase complex B (1:500 dilution; Invitrogen) antibodies at 4°C overnight. The blots were washed with TBS-T and then incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP or goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (1:1,000 dilution; Sigma) for 2 h at room temperature. The blots were washed five times with TBS-T, and the bands corresponding to protein content were visualized using chemiluminescent detection reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Statistics.

Unpaired Student's t-test was used for all analyses, unless otherwise indicated.

Chemicals.

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical, unless otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

Young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice appear phenotypically normal.

To identify whether a glycolytic skeletal muscle-specific reduction of Mn-SOD would alter gross phenotype, we measured body mass, the percentages of lean and fat mass, and muscle mass in young female (5- to 8-mo-old) and male (3- to 4-mo-old) TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. No difference in body mass was observed in female or male TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice compared with wild-type mice. Similarly, lean body mass, body fat, and gastrocnemius and soleus muscle mass in males and females were not significantly different from the corresponding values for wild-type mice (Table 1). In addition, there were no differences in muscle fiber morphology (Fig. 1B) or in the number of centrally located myofiber nuclei (indicative of muscle fiber regeneration) in sections of gastrocnemius from wild-type mice compared with sections of gastrocnemius from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice.

Table 1.

Phenotypic data in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice

| Muscle Mass/Body Mass, mg/g |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Mass, g | Lean Mass, % | Body Fat, % | Soleus | Gastrocnemius | |

| Males | |||||

| WT | 26.3±1.2 (5) | 81.1±1.3 (5) | 18.6±1.2 (5) | 0.4±0.03 (5) | 5.7±0.5 (5) |

| TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl | 27.3±1.9 (5) | 82.3±0.8 (5) | 17.3±0.9 (5) | 0.4±0.02 (5) | 6.0±0.4 (5) |

| Females | |||||

| WT | 21.3±0.3 (14) | 83.2±0.6 (23) | 16.5±0.6 (23) | 0.32±0.01 (14) | 5.7±0.1 (14) |

| TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl | 20.9±0.3 (14) | 81.7±0.6 (29) | 17.8±0.6 (29) | 0.33±0.02 (14) | 5.9±0.1 (14) |

Values are means ± SE of number of mice in parentheses. Female (5–8 mo old) and male (3–4 mo old) TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice were phenotypically normal compared with wild-type (WT) mice. No significant difference was observed for body mass, percent lean mass or percent body fat, or muscle mass normalized to body mass for soleus or gastrocnemius muscle.

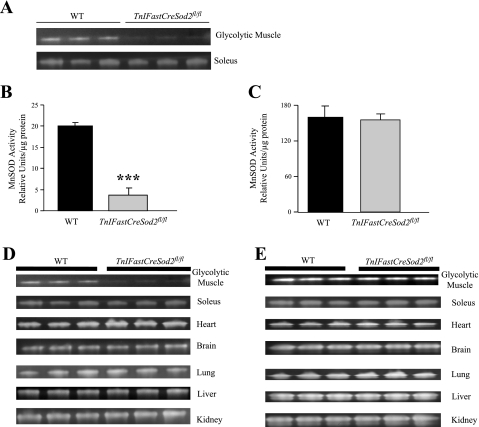

Mn-SOD is reduced selectively only in glycolytic skeletal muscle isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice.

To verify the tissue specificity of TnIFastiCre, Mn-SOD activity was measured in muscles consisting mostly of type IIB fibers, white gastrocnemius and quadriceps (“glycolytic muscle”), and a muscle enriched in type I + IIA fibers, soleus (8). Mn-SOD activity was reduced 82% in homogenates of mainly glycolytic skeletal muscle (Fig. 2, A and B) but was not significantly different in homogenates of soleus muscle (Fig. 2, A and C) isolated from young female TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice relative to soleus muscle homogenates isolated from wild-type mice. Mn-SOD activity was unchanged in all other tissues (Fig. 2D, Table 2). Cu,Zn-SOD activity was also measured to determine whether there was a potential upregulation of this form of SOD. Cu,Zn-SOD activity in homogenates of skeletal muscle containing glycolytic or oxidative fibers was not significantly different between wild-type and TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice, which indicates that the other mitochondrial isoform of SOD is not upregulated in response to a reduction in mitochondrial matrix Mn-SOD (Fig. 2E). Cu,Zn-SOD activity was also unchanged in all other tissues from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl relative to wild-type mice (Fig. 2E, Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Mn-SOD and Cu,Zn-SOD activity in young female TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. A: glycolytic and oxidative skeletal muscle Mn-SOD activity. Protein extracts from 3 wild-type and 3 TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice were analyzed using activity gels. B and C: quantification of Mn-SOD activity in glycolytic and oxidative skeletal muscle, respectively. Values are means ± SE. ***Significantly different (P < 0.001) from WT. D and E: Mn-SOD and Cu,Zn-SOD activity, respectively. Cu,Zn-SOD activity was not different in glycolytic or oxidative skeletal muscle and various other tissues. Protein extracts from 3 wild-type and 3 TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice were analyzed using activity gels.

Table 2.

Quantification of Mn-SOD and Cu,Zn-SOD activity in tissues isolated from wild-type and TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice

| Glycolytic Muscle | Soleus | Heart | Brain | Lung | Liver | Kidney | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn-SOD activity | |||||||

| WT | 20.0±0.8 | 160.5±18.6 | 324.0±28.5 | 148.9±11.1 | 74.9±15.2 | 77.1±1.2 | 269.6±5.0 |

| TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl | 3.6±1.7* | 155.3±10.4 | 337.4±20.2 | 170.1±12.9 | 86.0±8.5 | 78.5±2.4 | 334.8±35.3 |

| Cu,Zn-SOD activity | |||||||

| WT | 43.4±3.5 | 166.4±9.2 | 249.0±31.2 | 362.9±7.5 | 96.7±16.6 | 168.7±3.3 | 532.9±5.3 |

| TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl | 49.2±1.0 | 182.3±8.4 | 304.3±12.3 | 403.9±6.2 | 137.4±2.8 | 173.8±1.3 | 575.1±19.7 |

Values (means ± SE for 3 samples) are expressed as arbitrary units, relative to equal amounts of protein for wild-type and TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice (25–80 μg, depending on the tissue). Mn-SOD and Cu,Zn-SOD activities were determined using activity gels.

Significantly different (P < 0.001) from WT.

Mn-SOD is specifically reduced in type IIB skeletal muscle.

Measurement of Mn-SOD activity in muscle homogenates does not indicate the skeletal muscle fiber type in which Mn-SOD is specifically reduced. Using fluorescence-tagged antibodies for myosin heavy chain type I, IIA, and IIB and Mn-SOD, we measured the colocalization of immunofluorescence for myosin heavy chain type I, IIA, and IIB and Mn-SOD on cryostat sections of gastrocnemius with attached soleus (Fig. 3A). Types I, IIA, IIX, and IIB and Mn-SOD were analyzed by comparison of the relative fluorescence intensity of Mn-SOD followed by division by muscle fiber type area (Mn-SOD intensity/fiber type area). Total Mn-SOD intensity/fiber area was examined in sections from seven wild-type and four TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice (Fig. 3B). Expression of the TnIFast promoter has been shown to be more than fourfold higher in type IIB than type I + IIA and type IIX skeletal muscle fibers (22). Therefore, the greatest reduction in Mn-SOD content (as a result of TnIFastCre-mediated deletion) was expected in type IIB muscle fibers. The Mn-SOD intensity/fiber type area for Mn-SOD in type I + IIA skeletal muscle fibers from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice was reduced by 13% relative to wild-type mice, but the difference was not statistically significant. Mn-SOD activity in homogenates of soleus muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice was also reduced by 13%, but the difference was not statistically significant. Mn-SOD intensity/fiber type area for type IIX fibers from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice was reduced by 14%, but this value was not significantly different from wild-type mice. The Mn-SOD intensity/fiber type area in type IIB fibers from TnFastSod2fl/fl mice was significantly reduced by 70% relative to wild-type mice (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Mn-SOD is reduced specifically in type IIB skeletal muscle from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. A: representative cryostat sections of gastrocnemius (with attached soleus) immunostained for myosin heavy chain isoforms and Mn-SOD from wild-type and TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. Left: skeletal muscle fiber type overlay of mixed type I + IIA (white), type IIA (purple), type IIX (absence of fluorescence), and type IIB (green) skeletal muscle fibers. Middle: Mn-SOD immunofluorescence (red). Right: overlay of type IIB + Mn-SOD. B: quantification of Mn-SOD intensity/fiber type area for muscle sections from 7 wild-type and 4 TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. Sections were analyzed by comparison of relative fluorescence intensity of Mn-SOD localized to each respective fiber type, divided by muscle fiber-type area (Mn-SOD intensity/fiber type area). *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from WT.

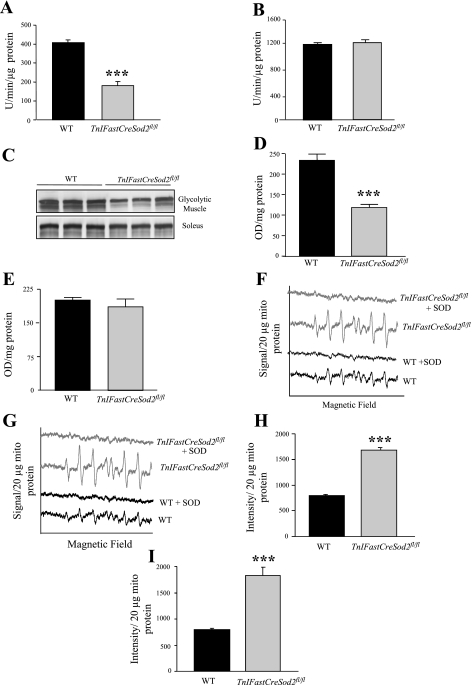

Aconitase activity and content are reduced in only glycolytic skeletal muscle isolated from young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice.

Aconitase activity has been shown to be sensitive to inactivation by superoxide (16–19). We hypothesized that Mn-SOD reduction would increase mitochondrial matrix superoxide content and decrease aconitase activity. Aconitase activity in homogenates of glycolytic skeletal muscle was reduced by 56% (Fig. 4A) and 52% (data not shown) in young male and female TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice, respectively, compared with aconitase activity in homogenates of glycolytic muscle isolated from wild-type mice. Aconitase protein content (Fig. 4, C and D) was reduced by 50% in homogenates of glycolytic skeletal muscle isolated from young female TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. Aconitase activity (Fig. 4B) and protein content (Fig. 4, C and E) in homogenates of soleus muscles were not significantly different relative to these levels in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. Soleus muscle consists exclusively of myosin heavy chain type I and IIA fibers (8). The absence of a reduction in aconitase activity in soleus muscles indicates that mitochondrial matrix superoxide content is not elevated in type I and IIA muscle fibers in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice.

Fig. 4.

Elevated oxidative stress in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. A and B: aconitase activity in glycolytic and oxidative muscles, respectively. Values are means ± SE for 5 samples. C: aconitase protein content. D and E: quantification of aconitase protein content in glycolytic and oxidative muscles, respectively. Values are means ± SE for 4 samples. OD, optical density. ***Significantly different (P < 0.001) from WT. F–I: mitochondrial superoxide release measured using the spin trap 5-diisopropoxyphosphoryl-5-methyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DIPPMPO) in glycolytic skeletal muscle. F and G: representative spectra with the complex I substrate glutamate + malate and the complex II substrate succinate + rotenone, respectively. H and I: quantification of electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra with substrates glutamate + malate and succinate + rotenone, respectively. Values are means ± SE for 5 samples. ***Significantly different (P < 0.001) from WT.

Mitochondria isolated from glycolytic skeletal muscle in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice release greater than twofold more superoxide than mitochondria isolated from glycolytic skeletal muscle in wild-type mice.

To directly measure mitochondrial superoxide content, we used EPR in conjunction with the superoxide-specific spin trap DIPPMPO. Mitochondria isolated from glycolytic skeletal muscle in young female and male (data not shown) TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice release 2.1- and 2.3-fold more superoxide with complex I-linked substrate (Fig. 4, F and H) and complex II-linked substrate (Fig. 4, G and I), respectively, than mitochondria isolated from glycolytic skeletal muscle in wild-type mice. Addition of Cu,Zn-SOD completely abolished the superoxide-derived EPR signal for complex I- and II-linked substrates (Fig. 4, F and G). Because exogenously added Cu,Zn-SOD is too large to cross the mitochondrial membrane(s), DIPPMPO detects superoxide that has been released from the mitochondria.

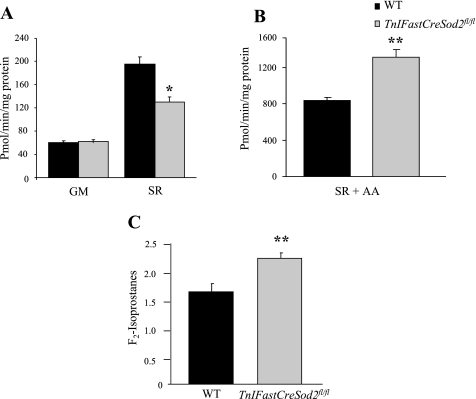

Rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production is reduced with complex II-linked substrate but increased in the presence of an inhibitor for complex III in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice.

The rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production was measured to further examine the oxidant burden in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. The rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production with the complex I-linked substrate glutamate + malate in mitochondria isolated from glycolytic skeletal muscle in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice was not different from that in wild-type mice (Fig. 5A). The rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production with the complex II-linked substrate succinate + rotenone was significantly reduced by 33% in mitochondria isolated from glycolytic skeletal muscle in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice relative to wild-type mice (Fig. 5A). However, succinate + rotenone + an inhibitor of the Qi site of complex III (AA) significantly increased the rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production by 56% in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice relative to wild-type mice (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Reactive oxygen species and oxidative damage assessment. A: rate of H2O2 production by mitochondria isolated from glycolytic skeletal muscle in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. Rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production was measured with Amplex Red and the substrates glutamate + malate (GM) and succinate + rotenone (SR). Values are means ± SE for 5 samples. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from WT. B: rate of H2O2 production by mitochondria incubated with the complex III inhibitor antimycin A (AA) in the presence of succinate + rotenone. Values are means ± SE for 5 samples. **Significantly different (P < 0.01) from WT. C: lipid peroxidation in tibialis anterior muscles isolated from young (3- to 4-mo-old) male TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. Values (ng F2-isoprostane/g tissue) are means ± SE for 4 samples. **Significantly different (P < 0.01) from WT.

Lipid oxidative damage is elevated in TA muscles isolated from young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice.

To determine whether a reduction in Mn-SOD content only in type IIB skeletal muscle would increase oxidative damage, we measured lipid peroxidation in TA muscles isolated from young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. TA muscle is composed of ∼65% myosin heavy chain type IIB (8). Lipid peroxidation was assessed by measurement of F2-isoprostane levels, which are stable, prostaglandin-like products formed nonenzymatically in vivo by the free radical-catalyzed peroxidation of arachidonic acid (34, 56). F2-isoprostanes increased significantly by 36% in TA muscles isolated from young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 5C).

Glycolytic muscle function and running capacity are reduced in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice.

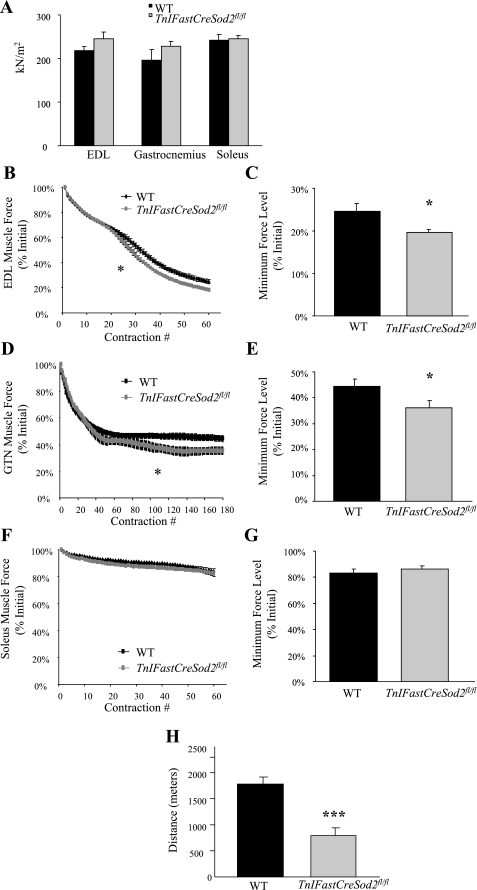

We hypothesized that the type IIB skeletal muscle-specific reduction in Mn-SOD content would alter contractile function only in glycolytic protein-containing muscles in TnFastSod2fl/fl mice. To test this hypothesis, we measured contractile force production in glycolytic (EDL and gastrocnemius) and oxidative (soleus) muscle. No significant difference in maximum specific isometric force was found in EDL, gastrocnemius, or soleus muscles from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Muscle function in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. A: maximum isometric specific force. Extensor digitorum longus (EDL), gastrocnemius, and soleus muscles were maximally activated, and force production was measured. Values are means ± SE for 5 EDL samples for wild-type and 8 EDL samples for TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice, 5 gastrocnemius samples for wild-type and 6 gastrocnemius samples for TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice, and 4 soleus samples for wild-type and 8 soleus samples for TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. B: force production as a function of time for EDL muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. Every 0.5 s, at a frequency of 100 Hz, the muscle was stimulated, such that there was 1 contraction every 5 s; force production was then measured. Starting with contraction 26, EDL muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice produced significantly less force than EDL muscles isolated from wild-type mice. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from WT. C: force level at the end of the 5-min contraction protocol expressed as percentage of initial force for EDL muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from WT. D: force production as a function of time for gastrocnemius (GTN) muscles in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. Starting with contraction 103, gastrocnemius muscles in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice produced significantly less force than gastrocnemius muscles in wild-type mice. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from WT. E: force level at the end of the 15-min contraction protocol expressed as percentage of initial force for gastrocnemius muscles in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from WT. F: force production by soleus muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice was not different at any time during the contraction protocol. G: force level at the end of the 5-min contraction protocol expressed as percentage of initial force for soleus muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. H: maximum endurance capacity test. TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice were run on a treadmill at a 12% grade at 12 m/min for 120 min, then speed was increased to 17 m/min for 10 min and, finally, to 22 m/min until exhaustion. Exhaustion was also defined biochemically, via blood glucose levels <60 mg/dl or blood lactate levels >12 mM. Values are means ± SE for 6 samples. ***Significantly different (P < 0.001) from WT.

The decline in force during repeated contractions by muscles from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice was compared by two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA. For EDL muscles, this analysis showed a significant (P < 0.001) decrease in force for TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice but a significant (P < 0.001) interaction between genotype and contraction number; that is, the effect of the repeated contractions on force was different between the genotypes. For EDL muscles of wild-type mice, force decreased until contraction 27, after which the ANOVA indicated no further statistically significant decline. In contrast, force production by EDL muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice continued to decline until contraction 34 (Fig. 6B). Force production was significantly (P < 0.05) different between EDL muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice starting at contraction 26. The average minimum force produced by EDL muscles from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice was 7% less than that produced by EDL muscles from wild-type mice (Fig. 6C).

A similar analysis showed that force production declined for gastrocnemius muscles of TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice (P < 0.001), with force levels leveling off after contraction 39 for muscles of wild-type mice, but only after contraction 66 for muscles of TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice (Fig. 6D). Force production was significantly (P < 0.05) different between gastrocnemius muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice starting at contraction 103. The average minimum force produced by gastrocnemius muscles in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice was 10% less than that produced by gastrocnemius muscles in wild-type mice (Fig. 6E).

Although soleus muscles from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice showed decreases (P < 0.001) in force during repeated contractions, the ability to produce force as a function of time was not different (P = 0.43) in soleus muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 6F). The average minimum force produced by soleus muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice was not significantly different from that produced by soleus muscles isolated from wild-type mice (Fig. 6G).

Muscle fatigue is defined as the decline in performance during contractile activity or exercise (13). To examine the in vivo significance of a glycolytic skeletal muscle-specific reduction of Mn-SOD content on muscle fatigue during exercise, young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice were run to exhaustion on a treadmill. For the TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice, the average time of exhaustion was 62.8 ± 11.8 min. Wild-type mice ran for 138.8 ± 4.9 min during treadmill testing (Fig. 6H). In addition, the distance run by the TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice was 55% less than the distance run by the wild-type animals (754.0 ± 129.4 vs. 1,807 ± 103.1 m, P < 0.001).

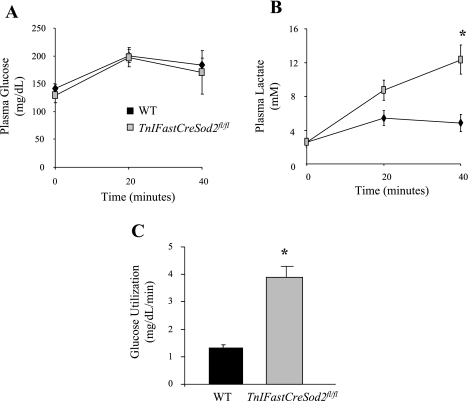

Changes in blood glucose and lactate are observed only during exercise in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice.

During submaximal exercise, mitochondrial dysfunction may lead to a shift from oxidative to glycolytic energy production, resulting in an elevation in serum lactate (15, 23). Blood lactate and glucose were measured before and during exercise to indirectly investigate mitochondrial function. No significant differences in fasting levels of blood glucose and lactate (data not shown) were identified in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice relative to wild-type mice. Nonfasted, preexercise levels of blood glucose (Fig. 7A) and lactate (Fig. 7B) were not different between TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice. Blood lactate levels in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice were elevated by 61% after 20 min of running, although the difference was just below the level of statistical significance. Lactate levels in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice became significantly different from wild-type mice after 40 min of running. In contrast, blood glucose levels in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice were not different from those in wild-type mice up to 40 min of running. However, TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice utilized glucose at a fourfold faster rate than wild-type mice from 40 min of running until exhaustion (Fig. 7C). The faster disappearance of glucose from the blood of TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice during exercise suggests that mitochondria from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice are not able to meet the aerobic energy demand, thereby leading to an increased reliance on glycolysis.

Fig. 7.

Metabolite levels in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice during exercise. A: blood glucose levels during exercise. Blood was removed from the tail vein of mice run for 0, 20, and 40 min and at exhaustion. Values are means ± SE for 6 samples. B: blood lactate levels were significantly elevated at all time points following 20 min of running in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. Values are means ± SE for 6 samples. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from WT. C: rate of blood glucose utilization from 40 min of running until exhaustion. Blood glucose levels were not different between TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice up to 40 min of running, but, from 40 min until exhaustion, TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice utilized glucose at a 4-fold faster rate than wild-type mice. Values are means ± SE for 6 samples. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from WT.

DISCUSSION

The main finding from the present study is that a reduction in Mn-SOD content in type IIB skeletal muscle is sufficient to increase glycolytic muscle mitochondrial oxidative stress and reduce glycolytic muscle contractile function and aerobic exercise capacity. Using TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice, we found an 82% reduction in Mn-SOD activity in white gastrocnemius and quadriceps (red fibers removed), muscles known to consist mainly of type IIB fibers (8). Mn-SOD activity in soleus muscle was not reduced in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice compared with wild-type mice, inasmuch as soleus muscle consists exclusively of type I and IIA fibers (8). From these data, it can be concluded that the specificity of the Mn-SOD reduction does not include type I or IIA muscle fibers. To measure Mn-SOD content in type IIX or IIB fibers, we performed immunohistochemistry on gastrocnemius (with attached soleus) muscle sections. Immunofluorescent analysis indicated that Mn-SOD content was significantly reduced by 70% only in type IIB muscle from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice relative to wild-type mice. No significant difference was observed for type I + IIA or type IIX Mn-SOD content between muscle sections from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice.

The 70% reduction in Mn-SOD content in type IIB skeletal muscle increased mitochondrial oxidative stress in muscles composed primarily of type IIB fibers, white gastrocnemius and quadriceps. A reduction in Mn-SOD would be expected to result in an increase in superoxide anion, the substrate for the enzyme. To determine whether levels of superoxide anion are increased in the mitochondrial matrix, we measured the activity of aconitase. At the active site of aconitase is a cubane [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster, in which three of the four irons are ligated to cysteine residues. The fourth iron is exposed to the aqueous media of the mitochondrial matrix and is open to attack from superoxide. Superoxide causes a one-electron oxidation of the iron-sulfur cluster, releasing the exposed iron in the ferrous state and inactivating the enzyme (16–19). Reduced aconitase activity has been observed during certain physiological and pathophysiological processes associated with increased generation of oxygen radicals (7, 40, 41, 48). Inhibition of aconitase may serve to reduce the supply of NADH for electron transport, thereby limiting the production of free radical species (47). Aconitase is protected from inactivation when Mn-SOD is present (18). We found a significant reduction in aconitase activity only in homogenates of glycolytic muscle isolated from young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. No significant difference in aconitase activity was found in homogenates of soleus muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice compared with homogenates of soleus muscles isolated from wild-type mice. It is important to note that aconitase protein content in homogenates of glycolytic skeletal muscle isolated from young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice was reduced by ∼50%. No significant difference in aconitase protein content was found in homogenates of soleus muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice compared with homogenates of soleus muscles isolated from wild-type mice. Aconitase activity has been reported to be indicative of mitochondrial matrix superoxide content, but, with a corresponding decrease in aconitase protein content, the decrease in aconitase activity only in glycolytic skeletal muscle isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice may be reflective of chronic mitochondrial matrix oxidative stress. The metabolic fate of aconitase under such conditions has been reported to be reversible posttranslational inactivation, release of a labile iron from the [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster, disassembly of the [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster, carbonylation, and protein degradation (7).

We then asked whether the decrease in Mn-SOD content in glycolytic muscle would result in changes in mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation as measured indirectly as H2O2 and also directly as mitochondrial superoxide release (via EPR). Interestingly, the rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production was reduced, but only with complex II substrate in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. In contrast, addition of an inhibitor for complex III, AA, in the presence of complex II substrate increased the rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production by 56% in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice relative to wild-type mice. An increased rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production has been observed in the presence of complex II substrate + AA when complex II is partially inhibited (12). Future experiments will address this issue. Furthermore, mitochondrial superoxide release was elevated more than twofold by mitochondria with use of complex I or complex II substrate in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice compared with mitochondria isolated from glycolytic muscle in wild-type mice. The net effect of elevated oxidative stress in young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice is a 36% increase in lipid oxidative damage. These data are in agreement with previous studies in conditional knockout mice lacking Mn-SOD in heart and skeletal muscle (H/M-Sod2−/−) (35). Mitochondria isolated from TA muscles in H/M-Sod2−/− mice produce fivefold more superoxide but 52% less H2O2, a result likely due to the reduction of Mn-SOD. In addition, lipid oxidative damage was found to be elevated in heart isolated from H/M-Sod2−/− mice (35).

Contractile muscle function was adversely affected in EDL and gastrocnemius muscles from young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice, whereas no differences were identified in contractile force production by soleus muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl compared with soleus muscles isolated from wild-type mice. Mn-SOD and aconitase activity in homogenates of soleus muscles isolated from wild-type mice were not different from Mn-SOD and aconitase activity in homogenates of soleus muscles isolated from TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. Collectively, these data suggest that type I + IIA muscle fibers (soleus) were unaffected in terms of oxidative stress, and, as a result, contractile function in soleus muscle was not altered. EDL muscles are composed of ∼50% type IIA and 50% IIB muscle fibers, gastrocnemius muscles are composed of ∼30% type IIA and 70% type IIB muscle fibers, and soleus muscles are composed exclusively of type I + IIA muscle fibers (8). In contrast, in muscles (EDL and gastrocnemius) that are composed of large numbers of type IIB muscle fibers, oxidative stress and oxidative damage were elevated and contractile function was reduced in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice compared with wild-type mice. Overall, these findings are consistent with our hypothesis that mitochondrial oxidative stress in glycolytic skeletal muscle is associated with deficits in contractile muscle function.

To investigate the in vivo significance of an Mn-SOD reduction only in type IIB skeletal muscle, treadmill testing was performed. Young TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice were found to be exercise intolerant, inasmuch as they ran a shorter distance and for less time than wild-type mice. These data implicate a causative role for skeletal muscle fiber type IIB-specific mitochondrial oxidative stress in aerobic exercise capacity.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is one possible explanation for the reduction in muscle function in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. Elevated serum lactate during exercise has been shown to be demonstrative of mitochondrial dysfunction (15, 23). Significantly more lactate was present in the blood of TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice after 40 min of running and at exhaustion. The blood lactate concentration in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice after 20 min of running was elevated by 61%, but significance was borderline. Blood glucose levels were not significantly different between TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl and wild-type mice from 0 to 40 min of running. However, a fourfold greater rate of glucose utilization was measured from 40 min of running until exhaustion in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. These data indicate that a critical point is reached at which mitochondrial metabolism is no longer able to maintain the ATP demand of submaximal exercise, and a shift from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism occurs. A greater reliance on glycolysis to meet the ATP demands of the cell will produce an increase in pyruvate content if mitochondrial dysfunction is present (15). Pyruvate enters the mitochondria, where it is oxidized by the tricarboxylic acid (citric acid) cycle. However, in the presence of mitochondrial dysfunction, elevated pyruvate may not be oxidized at the necessary rate by the tricarboxylic acid cycle and, via mass action, will form lactate. Cumulatively, these data suggest mitochondrial dysfunction in TnIFastCreSod2fl/fl mice. Future experiments will address the effect of a type IIB skeletal muscle-specific reduction of Mn-SOD on glycolytic muscle mitochondrial function.

Our results are consistent with previous studies in mice heterozygous for Sod2 (Sod2+/−) (30, 53, 54) and mice lacking Mn-SOD in both heart and skeletal muscle (H/M-Sod2−/−) (35). An association between increased mitochondrial oxidative stress and decreased exercise capacity has been shown for Sod2+/− and H/M-Sod2−/− mice. However, the tissue that is limiting with respect to muscle function in either animal model is unknown. In vitro studies of isolated skeletal muscle have shown that oxidative stress is limiting with respect to contractile function (3, 26, 32, 39, 46). In addition, mitochondrial oxidative stress and oxidative damage have been shown to be elevated in type II relative to type I skeletal muscle (2, 14, 38). These data suggest an association between type II skeletal muscle mitochondrial oxidative stress, oxidative damage, and reduced muscle function. Our results indicate that a type IIB skeletal muscle-specific reduction in Mn-SOD is sufficient to increase glycolytic muscle mitochondrial oxidative stress and is directly associated with reductions in contractile muscle function and aerobic exercise capacity.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Institute on Aging Grants P01 AG-020591 (to H. Van Remmen) and 5T3-AG-021890-02.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Corinne Price for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen DG, Lamb GD, Westerblad H. Skeletal muscle fatigue: cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev 88: 287– 332, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson EJ, Neufer PD. Type II skeletal myofibers possess unique properties that potentiate mitochondrial H2O2 generation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C844– C851, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrade FH, Reid MB, Allen DG, Westerblad H. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and dithiothreitol on contractile function of single skeletal muscle fibres from mouse. J Physiol 509: 565– 575, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Hoey BM, Butler J. The antioxidant action of N-acetylcysteine: its reaction with hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic Biol Med 6: 593– 597, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beauchamp C, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal Biochem 44: 276– 287, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharya A, Muller FL, Liu Y, Sabia M, Liang H, Song W, Jang YC, Ran Q, Van Remmen H. Denervation induces cytosolic phospholipase A2-mediated fatty acid hydroperoxide generation by muscle mitochondria. J Biol Chem 284: 46– 55, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulteau AL, Ikeda-Saito M, Szweda LI. Redox-dependent modulation of aconitase activity in intact mitochondria. Biochemistry 42: 14846– 14855, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkholder TJ, Fingado B, Baron S, Lieber RL. Relationship between muscle fiber types and sizes and muscle architectural properties in the mouse hindlimb. J Morphol 221: 177– 190, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalier F, Tordo P. 5-(Diisopropoxyphosphoryl)-5-methyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide, DIPPMPO, a crystalline analog of the nitrone DEPMPO: synthesis and spin trapping properties. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2: 2110– 2117, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies KJA, Quintanilha AT, Brooks GA, Packer L. Free radicals and tissue damage produced by exercise. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 107: 1198– 1205, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillard CJ, Litov RE, Savin WM, Tappel AL. Effects of exercise, vitamin E, and ozone on pulmonary function and lipid peroxidation. J Appl Physiol 45: 927– 932, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drose S, Brandt U. The mechanism of mitochondrial superoxide production by the cytochrome bc1 complex. J Biol Chem 283: 21649– 21654, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards RH, Hill DK, Jones DA, Merton PA. Fatigue of long duration in human skeletal muscle after exercise. J Physiol 272: 769– 778, 1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng J, Navratil M, Thompson LV, Arriaga E. Principal component analysis reveals age-related and muscle-type-related differences in protein carbonyl profiles of muscle mitochondria. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 63: 1277– 1288, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finsterer J, Shorny S, Capek J, Cerny-Zacharias C, Pelzl B, Messner R, Bittner RE, Mamoli B. Lactate stress test in the diagnosis of mitochondrial myopathy. J Neurol Sci 159: 176– 180, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner PR, Fridovich I. Superoxide sensitivity of the Escherichia coli aconitase. J Biol Chem 266: 19328– 19333, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner PR, Nguyen DH, White CW. Aconitase is a sensitive and critical target of oxygen poisoning in cultured mammalian cells and in rat lungs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 12248– 12252, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner PR, Raineri I, Epstein LB, White CW. Superoxide radical and iron modulate aconitase activity in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 270: 13399– 133405, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner PR. Aconitase: sensitive target and measure of superoxide. Methods Enzymol 349: 9– 23, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenstock CL, Miller RW. The oxidation of Tiron by superoxide anion. Kinetics of the reaction in aqueous solution in chloroplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 396: 11– 16, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hallauer PL, Bradshaw HL, Hastings KE. Complex fiber-type-specific expression of fast skeletal muscle troponin I gene constructs in transgenic mice. Development 119: 691– 701, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallauer PL, Hastings KE. TnIfast IRE enhancer: multistep developmental regulation during skeletal muscle fiber type differentiation. Dev Dyn 224: 422– 431, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haller RG, Henriksson KG, Jorfeldt L, Hultman E, Wilborn R, Sahlin K, Areskog NH, Gunder M, Ayyad K, Blomqvist G, Hall RE, Thuiller P, Kennaway NG, Lewis SF. Deficiency of skeletal muscle succinate dehydrogenase and aconitase. Pathophysiology of exercise in a novel human muscle oxidative defect. J Clin Invest 88: 1197– 1206, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikegami T, Suzuki Y, Shimizu T, Isono K, Koseki H, Shirasawa T. Model mice for tissue-specific deletion of the manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 296: 729– 736, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson MJ, Edwards RH, Symons MC. Electron spin resonance studies of intact mammalian skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta 847: 185– 190, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khawli FA, Reid MB. N-acetylcysteine depresses contractility and inhibits fatigue of diaphragm in vitro. J Appl Physiol 77: 317– 324, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King KL, Stanley WC, Rosca M, Kerner J, Hoppel CL, Febbraio M. Fatty acid oxidation in cardiac and skeletal muscle mitochondria is unaffected by deletion of CD36. Arch Biochem Biophys 467: 234– 238, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinugawa S, Wang Z, Kaminski PM, Wolin MS, Edwards JG, Kaley G, Hintze TH. Limited exercise capacity in heterozygous manganese superoxide dismutase gene-knockout mice: roles of superoxide anion and nitric oxide. Circulation 111: 1480– 1486, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klebl BM, Ayoub AT, Pette D. Protein oxidation, tyrosine nitration, and inactivation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in low frequency stimulated rabbit muscle. FEBS Lett 422: 381– 384, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansouri A, Muller FL, Liu Y, Ng R, Faulkner J, Hamilton M, Richardson A, Huang TT, Epstein CJ, Van Remmen H. Alterations in mitochondrial function, hydrogen peroxide release and oxidative damage in mouse hind-limb skeletal muscle during aging. Mech Ageing Dev 127: 298– 306, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McArdle A, Pattwell D, Vasilaki A, Griffiths RD, Jackson MJ. Contractile activity-induced oxidative stress: cellular origin and adaptive responses. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C621– C627, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moopanar TR, Allen DG. Reactive oxygen species reduce myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity in fatiguing mouse skeletal muscle at 37°C. J Physiol 564: 189– 199, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller FL, Liu Y, Abdul-Ghani MA, Lustgarten MS, Bhattacharya A, Jang YC, Van Remmen H. Complex III releases superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. Biochem J 409: 491– 499, 2004. 17916065 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller FL, Song W, Liu Y, Chaudhuri A, Pieke-Dahl S, Strong R, Huang TT, Epstein CJ, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Csete M, Faulkner JA, Van Remmen H. Absence of CuZn superoxide dismutase leads to elevated oxidative stress and acceleration of age-dependent skeletal muscle atrophy. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 1993– 2004, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nojiri H, Shimizu T, Funakoshi M, Yamaguchi O, Zhou H, Kawakami S, Ohta Y, Sami M, Tachibana T, Ishikawa H, Kurosawa H, Kahn RC, Otsu K, Shirasawa T. Oxidative stress causes heart failure with impaired mitochondrial respiration. J Biol Chem 281: 33789– 33801, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orhan H, van Holl B, Krab B, Moeken J, Vermeulen NP, Hollander P, Meerman JH. Evaluation of a multi-parameter biomarker set for oxidative damage in man: increased urinary excretion of lipid, protein, and DNA oxidation products after one hour of exercise. Free Radic Res 38: 1269– 1279, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pette D, Staron RS. Cellular and molecular diversities of mammalian skeletal muscle fibers. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 116: 1– 76, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Picard M, Csukly K, Robillard ME, Godin R, Ascah A, Bourcier-Lucas C, Burelle Y. Resistance to Ca2+-induced opening of the permeability transition pore differs in mitochondria from glycolytic and oxidative muscles. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R659– R668, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reid MB, Haack KE, Franchek KM, Valberg PA, Kobzik L, West MS. Reactive oxygen in skeletal muscle. I. Intracellular oxidant kinetics and fatigue in vitro. J Appl Physiol 73: 1797– 1804, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sadek HA, Humphries KM, Szweda PA, Szweda LI. Selective inactivation of redox-sensitive mitochondrial enzymes during cardiac reperfusion. Arch Biochem Biophys 406: 222– 228, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schapira AH. Mitochondrial involvement in Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease and hereditary spastic paraplesia and Freidreich's ataxia. Biochim Biophys Acta 1410: 159– 170, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schiaffino S, Saggin L, Viel A, Ausoni S, Sartore S, Gorza L. Muscle fiber types identified by monoclonal antibodies to myosin heavy chains. In: Biochemical Aspects of Physical Exercise, edited by Benzi G, Packer L, Siliprandi N. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1986, p. 27– 34 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Myosin isoforms in mammalian skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 77: 493– 501, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwenk F, Baron U, Rajewsky K. A cre-transgenic mouse strain for the ubiquitous deletion of loxP-flanked gene segments including deletion in germ cells. Nucleic Acids Res 23: 5080– 5081, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimshek DR, Kim J, Hübner MR, Spergel DJ, Buchholz F, Casanova E, Stewart AF, Seeburg PH, Sprengel R. Codon-improved Cre recombinase (iCre) expression in the mouse. Genesis 32: 19– 26, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shindoh C, Dimarco A, Thomas A, Manubray P, Supinski G. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on diaphragm fatigue. J Appl Physiol 68: 2107– 2113, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skulachev VP. Membrane-linked systems preventing superoxide formation. Biosci Rep 17: 347– 366, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sipos I, Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Quantitative relationship between inhibition of respiratory complexes and formation of reactive oxygen species in isolated nerve terminals. J Neurochem 84: 112– 118, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Supinski G, Nethery D, Stofan S, Szweda L, Dimarco A. Oxypurinol administration fails to prevent free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation during loaded breathing. J Appl Physiol 87: 1123– 1131, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taicher GZ, Tinsley FC, Reiderman A, Heiman ML. Quantitative magnetic resonance (QMR) method for bone and whole-body-composition analysis. Anal Bioanal Chem 377: 990– 1002, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tinsley FC, Taicher GZ, Heiman ML. Evaluation of a quantitative magnetic resonance method for mouse whole body composition analysis. Obes Res 12: 150– 160, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsakiris S, Parthimos T, Parthimos N, Tsakiris T, Schulpis KH. The beneficial effect of l-cysteine supplementation on DNA oxidation induced by forced training. Pharmacol Res 53: 386– 390, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Remmen H, Salvador C, Yang H, Huang TT, Epstein CJ, Richardson A. Characterization of the antioxidant status of the heterozygous manganese superoxide dismutase knockout mouse. Arch Biochem Biophys 363: 91– 97, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Remmen H, Ikeno Y, Hamilton M, Pahlavani M, Wolf N, Thorpe SR, Alderson NL, Baynes JW, Epstein CJ, Huang TT, Nelson J, Strong R, Richardson A. Life-long reduction in MnSOD activity results in increased DNA damage and higher incidence of cancer but does not accelerate aging. Physiol Genomics 16: 29– 37, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vassilakopoulos T, Deckman G, Kebbewar M, Rallis G, Harfouche R, Hussain SN. Regulation of nitric oxide production in limb and ventilatory muscles during chronic exercise training. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L452– L457, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ward WF, Qi W, Van Remmen H, Zackert WE, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Richardson A. Effects of age and caloric restriction on lipid peroxidation: measurement of oxidative stress by F2-isoprostane levels. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60: 847– 851, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams MD, Van Remmen H, Conrad CC, Huang TT, Epstein CJ, Richardson A. Increased oxidative damage is correlated to altered mitochondrial function in heterozygous manganese superoxide dismutase knockout mice. J Biol Chem 273: 28510– 28515, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yutzey KE, Kline RL, Konieczny SF. An internal regulatory element controls troponin I gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 9: 1397– 1405, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou Z, Diwu N, Panchuk-Voloshina, Haugland RP. A stable nonfluorescent derivative of resorufin for the fluorometric determination of trace hydrogen peroxide: applications in detecting the activity of phagocyte NADPH oxidase and other oxidases. Anal Biochem 253: 162– 168, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]