Abstract

CONTEXT

The prevalence of depression is disproportionately higher in older women than men, yet the reasons for this gender difference are not clear.

OBJECTIVE

We sought to determine whether the higher burden of depression among older women than men might be attributable to gender differences in the onset, i.e., first or recurrent episodes, or persistence of depression and/or to differential mortality among those who are depressed.

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study.

SETTING

General community in greater New Haven, Connecticut from March 1998 to August 2005.

PARTICIPANTS

754 persons, aged 70 years or older, who were evaluated at 18-month intervals for 72 months.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

The three outcome states were depressed, non-depressed and death, with scores ≥20 and <20 on the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale denoting depressed and non-depressed, respectively. The association between gender and the likelihood of six possible transitions, namely from non-depressed or depressed to non-depressed, depressed, or death was evaluated over time.

RESULTS

The prevalence of depression was substantially higher among women than men at each of the five time points (p<0.001). In most cases, transitions between the non-depressed and depressed states were characterized by moderate to very large absolute changes in depression scores, i.e., at least 10 points. Adjusting for other demographic characteristics, women had a higher likelihood of transitioning from non-depressed to depressed (odds ratio=2.02; 95% Confidence Interval 1.39, 2.94) and lower likelihood of transitioning from depressed to non-depressed (odds ratio=0.27; 95% confidence interval 0.13, 0.56) or death (odds ratio=0.24; 95% confidence interval 0.09–0.60).

CONCLUSIONS

Among older persons, the higher burden of depression in women than men appears to be attributable to a greater susceptibility to depression and, once depressed, to more persistent depression and a lower probability of death.

Keywords: depression, gender differences, older persons, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Whereas major depression affects only about 1% to 2% of community-dwelling older persons,1,2 clinically significant depressive symptoms are more common. Often referred to as “depressed mood” or simply “depression,” clinically significant depressive symptoms affect between 8% to 20% of this population3–10 and are highly morbid.11–23 The burden of depression, however, is disproportionately higher among older women than men.2,24–31 Despite an expanding knowledge base about late-life depression,7,32 the reasons for this gender difference have remained poorly defined.

Efforts to explain the gender difference in the prevalence of depression have focused largely on evaluating associations between gender and exposure to risk factors for depression,28 comparing gender differences in the perception of symptoms,33,34 and identifying environmental and personality factors that mediate the relationship between gender and depression.35 An alternative approach, which has not yet been formally evaluated, is to determine whether gender differences in depression onset, persistence, and mortality might collectively account for the higher burden of depression among older women. While prior studies have evaluated gender differences in depression onset and persistence 9,36–40 or in mortality among those who are depressed,18,41,42 they have been limited by the availability of data at only two time points, often at widely spaced intervals9,18,36–38,40,42 or a short duration of follow-up.36 To our knowledge, only one study has considered the potentially fluctuating course of depression over time,39 but this study had a short duration of follow-up and included only depressed persons in its sample.

The objective of this prospective study was to determine whether the higher burden of depression among older women than men is attributable to gender differences in the onset of depression, i.e., first or recurrent episodes, or persistence of depression over time and/or to differential mortality among those who are depressed. To achieve our objective, we evaluated possible transitions between three states – not depressed, depressed, and death – at 18-month intervals for six years among a large cohort of older men and women.

METHODS

Study Population

Participants were members of the Precipitating Events Project (PEP), a longitudinal study of 754 community-dwelling persons aged 70 years or older.43 The assembly of the cohort has been described in detail elsewhere.43 In brief, potential participants were identified from 3,157 age-eligible members of a health plan in New Haven, Connecticut. The primary inclusion criteria were English speaking and requiring no personal assistance with four key activities of daily living (i.e., bathing, dressing, transferring from a chair, and walking). The participation rate was 75.2%.43 During 6-years of follow-up occurring between March 1998 and August 2005, 232 participants died after a median of 48 months, 27 dropped out of the study after a median of 24 months, and 18 were subsequently excluded due to participation by proxy after a median of 32 months. The Human Investigation Committee at Yale University approved the study.

Data Collection

The current study included data collected during in-home assessments that were completed at baseline and every 18 months for up to 72 months by trained research nurses who used standard procedures that have been described in detail elsewhere.44 Demographic data included age, gender, race, and educational level. Medical comorbidity was ascertained based on the presence of nine self-reported, physician-diagnosed chronic conditions, including hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes, hip fracture, arthritis, chronic lung disease, and cancer (other than minor skin cancer). Cognitive status was assessed with the Folstein Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE).45 Deaths were ascertained by review of local obituaries and/or from an informant.

Assessment of Depression

The 11-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression (CES-D) scale46 was used to assess depressive symptoms in the previous week during each of the five time points (i.e., baseline, and 18, 36, 54, and 72 months). Prior studies of older persons report test-retest reliability statistics of 0.82 or higher on the shortened form of the CES-D.47,48 As in several prior studies,17,18,49 scores were transformed using the procedure recommended by Kohout et al.50 to make it compatible with the full 20-item instrument. Total scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. While a CES-D score of 16 is most commonly used to distinguish between depressed and non-depressed persons in mixed-age samples, a cut point of 20 offers a more stringent approach to the classification of depressed mood among older persons.14,17,51–53 A CES-D score of 20 or higher has been shown to predict outcomes related to well-being and functioning as well as diagnostic measures of depression39 and has been used in several prior epidemiologic studies of depression in the elderly.11,17,53 Data on depression were complete for 100% of the participants at baseline and 95%, 93%, 91%, and 90% of the non-decedents at 18, 36, 54, and 72 months, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

We determined the association, at baseline, between depression and the characteristics of the participants using chi-square or t-test statistics. We then compared the prevalence of depression between men and women at each time point using the chi-square statistic. For each of the 18-month intervals, we calculated rates by gender for six possible transitions, defined on the basis of the three outcome states: non-depressed, depressed and death. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact statistics were used to evaluate the bivariate associations between gender and the six possible transitions for each time interval. Because the number of participants was relatively small for some of the transitions, the power to detect statistically significant differences in the transition rates according to gender may not have been adequate for all comparisons. Furthermore, to account for the large number of comparisons, p-values were determined according to the Hochberg method.54

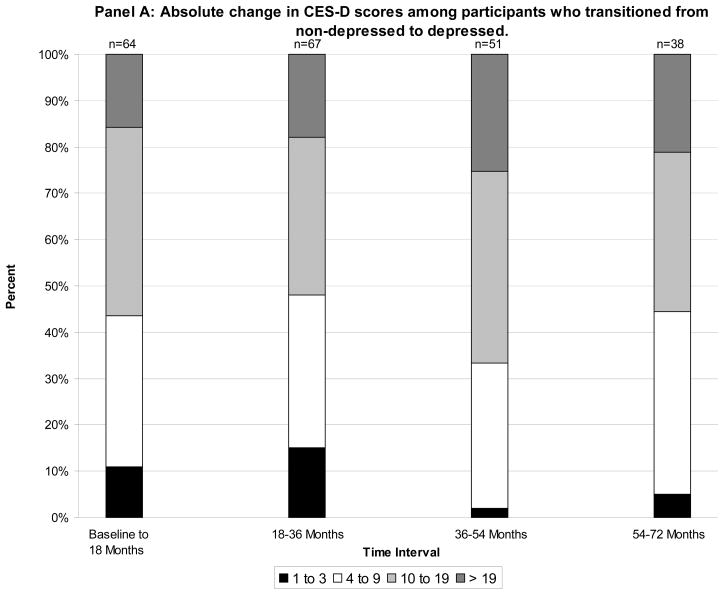

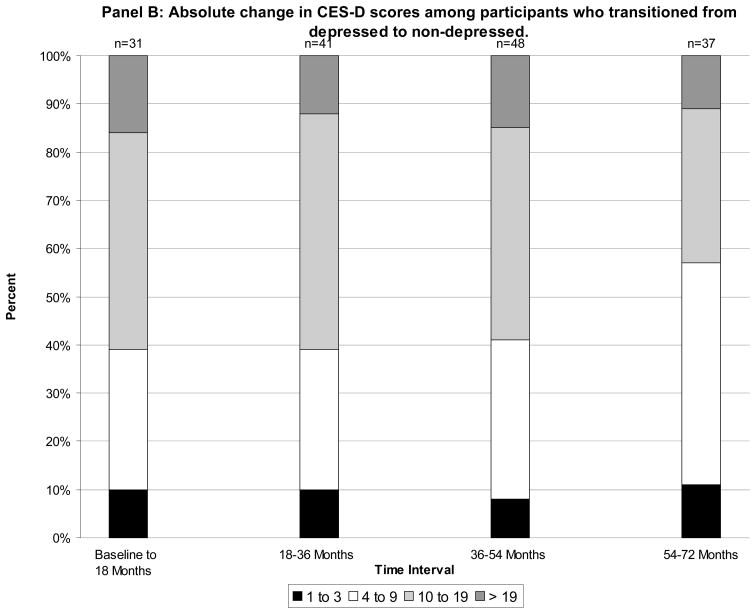

To determine whether the observed transitions were clinically meaningful, we calculated the percentage of transitions that represented absolute changes in the CES-D scores of 1 to 3 (small), 4 to 9 (moderate), 10 to 19 (large), and 20 or more points (very large), respectively, for each time interval, and we subsequently determined whether the distribution of these percentages differed by gender using the chi-square statistic.

Lastly, we evaluated the association between gender and the likelihood of the six possible transitions over time using longitudinal methods that optimized statistical power and accounted for potential correlation among depression scores. Specifically, we ran generalized multinomial logit models for nominal outcomes that were estimated with Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) and used exchangeable correlation structures.55 The first longitudinal model included participants who were non-depressed at the beginning of any 18-month time interval, with participants who were non-depressed during the entire interval (i.e., at two consecutive 18-month time points) serving as the comparison group. The second longitudinal model included participants who were depressed at the beginning of any 18-month time interval, with participants who were depressed during the entire interval serving as the comparison group. The magnitude of association was denoted by odds ratios, which were subsequently adjusted for age, race (White vs. other), education, number of chronic conditions, and MMSE score.

All statistical tests were two-tailed and p-values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. The longitudinal models were performed using Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN) software version 9.0,56 and all other analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software version 9.1.57

RESULTS

Table 1 provides the characteristics of the study participants over the course of six years. At baseline, participants had a mean age of about 80 years; about two-thirds were women, and most were white. On average, participants had a high school education, two chronic conditions, and were cognitively intact. Participants who were depressed at baseline were less educated, had more chronic conditions, had lower MMSE scores, and were more likely to be women as compared to the non-depressed participants (p<0.05) (results not shown). The proportion of women did not change appreciably over time, while the burden of chronic conditions increased modestly. At baseline and each subsequent time point, the prevalence of depression was substantially higher among women than men (p<0.001), with the greatest absolute difference observed at 54 months. Furthermore, of the 269 (35.7%) participants who were depressed at some point during the 72 months of follow-up, 48 (17.8%), 30 (11.1%), 17 (6.3%) and 12 (4.5%) were depressed during two, three, four, and five consecutive time points, respectively, with a greater number of women experiencing depression at subsequent time points as compared to men (p<0.01).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants over Six Years.*

| Characteristic | Baseline (N=754) | 18 Months (N=675) | 36 Months (N=612) | 54 Months (N=538) | 72 Months (N=471) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ±SD | 78.4 ± 5.3 | 79.6 ± 5.1 | 80.9 ± 5.1 | 82.2 ± 4.9 | 83.7 ± 4.8 |

| Female, n (%) | 487 (64.6) | 439 (65.0) | 405 (66.2) | 359 (66.7) | 310 (65.8) |

| Non-Hispanic white, n (%) | 682 (90.5) | 609 (90.2) | 550 (89.9) | 483 (89.8) | 423 (89.8) |

| Education (years), mean ±SD | 12.0 ± 2.9 | 12.0 ± 2.8 | 12.0 ± 2.8 | 12.0 ± 2.8 | 12.1 ± 2.8 |

| Chronic conditions,† mean ±SD | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 2.2 ± 1.3 | 2.2 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 1.3 |

| Cognitive status score, ‡ mean ±SD | 26.8 ± 2.5 | 26.4 ± 2.9 | 26.3 ± 3.4 | 25.5 ± 4.0 | 25.3 ± 4.6 |

| Depression, n (%)§ | |||||

| Men | 14 (5.2) | 17 (7.2) | 22 (10.6) | 13 (7.3) | 17 (10.6) |

| Women | 86 (17.7) | 99 (22.6) | 102 (25.2) | 96 (26.7) | 74 (23.9) |

The cumulative number of decedents was 46 at 18 months, 98 at 36 months, 166 at 54 months, and 232 at 72 months.

The 9 self-reported, physician-diagnosed chronic conditions included: hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes, hip fracture, arthritis, chronic lung disease, and cancer (other than minor skin cancer).

As assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

Prevalence rates are based on the number of men and women, respectively. At each time point, the rates were substantially higher among women then men (p<0.001).

Table 2 provides the transition rates between the three outcome states over the 18-month intervals according to gender. With only a few exceptions, the rates were comparable across the four intervals. Among participants who were non-depressed, women generally had higher rates of transitioning to depressed and lower rates of remaining non-depressed or transitioning to death. Among those who were depressed, women had higher rates of remaining depressed and lower rates of transitioning to non-depressed or death, with one exception. Women had a higher rate of transitioning from depressed to death during the 54–72 month interval, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

| 0–18 months | 18–36 months | 36–54 months | 54–72 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Non-Depressed to: | ||||||||

| N=244 | N=386 | N=212 | N=329 | N=183 | N=289 | N=164 | N=257 | |

| Non-Depressed | ||||||||

| n | 213 | 315 | 175 | 267 | 150 | 227 | 137 | 205 |

| % | 87.3 | 81.6 | 82.5 | 81.1 | 82.0 | 78.6 | 83.6 | 79.8 |

| p-value | 0.47 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | ||||

| Depressed | ||||||||

| n | 12 | 52 | 19 | 48 | 11 | 40 | 12 | 26 |

| % | 4.9 | 13.5 | 9.0 | 14.6 | 6.0 | 13.8 | 7.3 | 10.1 |

| p-value | 0.006 | 0.47 | 0.08 | 0.74 | ||||

| Death | ||||||||

| n | 19 | 19 | 18 | 14 | 22 | 22 | 15 | 26 |

| % | 7.8 | 4.9 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 12.0 | 7.6 | 9.1 | 10.1 |

| p-value | 0.74 | 0.42 | 0.74 | 0.74 | ||||

| Depressed to: | ||||||||

| N=14 | N=77 | N=16 | N=93 | N=20 | N=99 | N=13 | N=91 | |

| Non-Depressed | ||||||||

| n | 6 | 25 | 8 | 33 | 15 | 33 | 7 | 30 |

| % | 42.9 | 32.5 | 50.0 | 35.5 | 75.0 | 33.3 | 53.8 | 33.0 |

| p-value | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.006 | 0.99 | ||||

| Depressed | ||||||||

| n | 5 | 47 | 3 | 51 | 2 | 53 | 5 | 47 |

| % | 35.7 | 61.0 | 18.8 | 54.8 | 10.0 | 53.5 | 38.5 | 51.6 |

| p-value | 0.63 | 0.08 | 0.004 | 0.99 | ||||

| Death | ||||||||

| n | 3 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| % | 21.4 | 6.5 | 31.0 | 9.7 | 15.0 | 13.1 | 7.7 | 14.3 |

| p-value | 0.72 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.99 | ||||

Transition rates were calculated for participants who had data on depression or death at each of the two time points defining the relevant follow-up interval.

P-values were determined according to the Hochberg method for multiple comparisons.

As shown in the Figure (Panel A), the majority of transitions from non-depressed to depressed were based on moderate to very large absolute changes in CES-D scores, i.e. at least 10 points; small changes in the range of 1 to 3 points were observed for no more than 15% of the transitions during any of the 18-month intervals. Similar results were found for transitions from depressed to non-depressed Figure 1 (Panel B). There were no significant differences in the distribution of change scores by gender for either set of transitions (results not shown).

Figure.

Change in CES-D scores among participants who transitioned from non-depressed to depressed (Panel A) and from depressed to non-depressed (Panel B).

Table 3 presents the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios derived from the longitudinal models evaluating the association between gender and the likelihood of the six transitions between the three outcome states over the course of six years. Among those who were non-depressed, women were more likely to transition to a depressed state, with an adjusted odds ratio of 2.02 (95% CI: 1.39, 2.94). Among those who were depressed, women were less likely to transition to non-depressed and to death, with adjusted odds ratios of 0.27 (95% CI: 0.13, 0.56) and 0.24 (95% CI: 0.09, 0.60, respectively. There was no significant association between gender and transitioning from non-depressed to death.

Table 3.

Longitudinal Assessment of Transitions Over the Course of Six Years Among Women Relative to Men.

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio* | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition | ||||||

| Non-depressed to: | ||||||

| Non-depressed | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - |

| Depressed | 2.06 | 1.45, 2.92 | <0.001 | 2.02 | 1.39, 2.94 | <0.001 |

| Death | 0.74 | 0.54, 1.02 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.56, 1.12 | 0.19 |

| Depressed to: | ||||||

| Depressed | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - |

| Non-depressed | 0.28 | 0.15, 0.51 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 0.13, 0.56 | <0.001 |

| Death | 0.25 | 0.11, 0.55 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.09, 0.60 | 0.003 |

Adjusted for age (years), race (White vs. other), education (years), number of chronic conditions, and MMSE score.

COMMENT

In this longitudinal study, which included multiple assessments over the course of six years, we confirmed that the prevalence of depression is substantially higher among older women than men. More importantly, we found that this gender difference is attributable to a greater susceptibility to depression and, once depressed, to more persistent depression and a lower probability of death in older women.

Late-life depression is a significant clinical and public health problem because it is common,6–9,37 costly,58,59 and associated with disability8,15,17,19 and other adverse outcomes including rehospitalization and death among those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,60 myocardial infarction,61–63 and stroke.64 Despite these negative consequences, there is considerable uncertainty about why the prevalence of late-life depression is disproportionately higher in women than men. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to evaluate whether gender differences in depression onset, persistence, and mortality might collectively account for the higher burden of depression among older women.

With one exception,9 prior studies of community-living older persons have found no evidence of a gender difference in either the onset9,36,37,40 or persistence9,36,38,39 of depression. These studies, however, have generally included only one follow-up assessment of depression at an interval no shorter than two years.9,37,39,40 The inability to account for fluctuations in depression over time (i.e., recurrent depression) may have a substantial impact on estimates of depression onset. In contrast, we evaluated transitions into and out of depression states at 18-month intervals for six years and used longitudinal methods that addressed potential problems related to low power for any single time interval. Low self-esteem, helplessness, and low social status have been shown to differentially increase the risk of depression onset in women younger than age 65 years as compared with men of the same age.65 Additional research is needed to determine the etiology of gender differences in depression onset among older persons.

The consistency of our findings over four different time intervals provides strong evidence that depression is more likely to persist in older women than men. This gender difference in the persistence of depression is somewhat surprising since women are more likely than men to receive both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment for depression.66–70 Whether women are treated less aggressively than men for late-life depression or are less likely to respond to conventional treatment is not known,72,73 but should be the focus of future research. In addition, nearly 40% of the depressed participants in this study were depressed during at least two consecutive time points, highlighting the need to initiate and potentially maintain antidepressant treatment after resolution of the initial depressive episode.74

As in prior studies,18,41,42 we found that older women are less likely than men to die when depressed, providing a third explanation for the gender difference in the prevalence of depression. Of course, older men generally have higher mortality rates than older women irrespective of depression,75 as was observed in the current study. Nonetheless, the mortality difference we observed by gender was marked, with a nearly three-fold difference in the odds ratios for participants who were depressed as compared with those who were not.

The availability of five waves of data over a six-year period provides the best information, to date, on how depression onset, persistence, and mortality collectively influence the prevalence of depression. Because these factors are highly inter-related, we were unable to determine their relative contribution to the prevalence of depression. Prevalence, for example, is a function of incidence and duration, while duration is a function of persistence and mortality.

Because information regarding participants’ depression status prior to the baseline interview was not available, we cannot determine if participants’ first transition from a non-depressed to a depressed state represents incident depression. Given the preponderance of depression among women as compared with men in non-elderly samples,76–78 it is possible that our findings represent the continuation of a gender-related pattern of depression established earlier in life. Future studies should evaluate whether gender differences in the onset and persistence of depression during youth and middle-age may help to explain reasons for gender differences in depression patterns in older age.

In the absence of a diagnostic measure, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID),79 we were unable to determine the prevalence of major depression among the study participants. However, we used a cut point of 20 or greater on the CES-D scale to identify depressed participants at each time point. This cut point has previously been shown to enhance the likelihood of detecting depressed mood among community-living older persons.14,17,51–53,80 Furthermore, the moderate to very large changes in the CES-D scores over time, regardless of gender, indicate clinically meaningful transitions between depression states. Of note, the baseline rate of depression in our study is somewhat higher than rates reported in other studies of older persons that have used the more stringent cut point of 20 or greater on the CES-D.17,80 This difference may be explained by the higher mean age and more diverse racial composition of our sample as compared with these other studies.

Because our study participants were members of a single health plan and were non-disabled and at least 70 years of age at baseline, the generalizability of our findings to other older adult populations may be questioned. As previously noted, however,43 the demographic characteristics of our study population, including years of education, closely mirror those of persons aged 70 years or older in New Haven county, which, in turn, are comparable to those in the United States as a whole, with the exception of race. New Haven county has a larger proportion of non-Hispanic whites in this age group than in the United States, 91% vs. 84%.81 Given that African-Americans have a higher prevalence of persistent depression as compared with non-Hispanic whites,82 future research should explore whether the relationship between gender and transitions across depression states is modified by race using data that more closely reflects the racial composition of older adults in the U.S. Furthermore, generalizability depends not only on the characteristics of the study population but also on its stability over time.83 The high participation rate, completeness of data collection and low rate of attrition for reasons other than death all enhance the generalizability of our findings,82 and at least partially offset the absence of a population-based sample.

In summary, the higher burden of depression in older women than men appears to be attributable to a greater susceptibility to depression, and once depressed, to more persistent depression and lower probability of death. Additional research is needed to determine the etiology of these gender differences so that more effective strategies can be developed to detect and manage depression in this population.

Acknowledgments

We thank Denise Shepard, BSN, MBA, Andrea Benjamin, BSN, Paula Clark, RN, Martha Oravetz, RN, Shirley Hannan, RN, Barbara Foster, and Alice Van Wie for assistance with data collection; Evelyne Gahbauer, MD, MPH for data management and programming; Wanda Carr and Geraldine Hawthorne for assistance with data entry and management; Peter Charpentier, MPH for development of the participant tracking system; and Joanne McGloin, MDiv, MBA for leadership and advice as the Project Director.

Funding/Support: The work for this report was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R37AG17560, R01AG022993, 5T32AG019134). The study was conducted at the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG21342). Dr. Gill is the recipient of a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24AG021507) from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Barry is a 2007 Brookdale Leadership in Aging Fellow.

Role of Sponsors: The organizations funding this study had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Presented as a poster presentation at the 2006 Gerontological Society of America Meetings, Dallas, TX; November 17, 2006.

Author Contributions: Dr. Gill had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. None of the authors has any conflicts of interest including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The specific contributions are enumerated in the authorship, financial disclosure, and copyright transfer form.

Contributor Information

Lisa C. Barry, Email: lisa.barry@yale.edu.

Heather G. Allore, Email: heather.allore@yale.edu.

Zhenchao Guo, Email: zhenchao.guo@yale.edu.

Martha L. Bruce, Email: mbruce@med.cornell.edu.

Thomas M. Gill, Email: gill@ynhh.org.

References

- 1.Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, van Tilburg T, et al. Major and minor depression in later life: a study of prevalence and risk factors. J Affect Disord. 1995;36:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beekman ATF, Copeland JRM, Prince MJ. Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:307–311. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blazer D, Williams C. The epidemiology of dysphoria and depression in an elderly population. Am J Psychiatr. 1980;137:439–444. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murrell S, Himmelfarb S, Wright K. Prevalence of depression and its correlates in older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117:173–185. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blazer D, Swartz M, Woodbury M, et al. Depressive symptoms and depressive diagnoses in a community population. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1988;45:1078–1084. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blazer D, Burchett B, Service C, et al. The association of age and depression among the elderly: an epidemiologic exploration. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1991;46:M210–215. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.6.m210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2003;58:249–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkman LF, Berkman CS, Kasl S, et al. Depressive symptoms in relation to physical health and functioning in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:372–388. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Geerlings SW, et al. Emergence and persistence of late life depression: a 3-year follow-up of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Affect Dis. 2001;65:101–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, et al. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264:2524–2528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Braam AW, et al. Consequences of major and minor depression in later life: a study of disability, well-being, and service utilization. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1065–1077. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, Rozal GPM, et al. Psychiatric status and 9-year mortality in the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:716–721. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruce ML, Leaf PJ. Psychiatric disorders and 15 month mortality in a community sample of older adults. Am J Pub Health. 1989;79:727–730. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruce ML, Ten Have T, Reynolds CF, et al. A Randomized Trial to Reduce Suicidal Ideation and Depressive Symptoms in Depressed Older Primary Care Patients: The PROSPECT Study. JAMA. 2004;291:1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruce ML, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, et al. The Impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Am J Pub Health. 1994;84:1796–1799. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penninx BWJH, Guralnik JM, Mendes de Leon CF, et al. Cardiovascular events and mortality in newly and chronically depressed persons >70 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:988–994. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Penninx BWJH, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 1998;279:1720–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penninx BWJH, Geerlings MI, Deeg DJH, et al. Minor and major depression and the risk of death in older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:889–895. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geerlings SW, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, et al. The longitudinal effect of depression on functional limitations and disability in older adults: an eight-wave prospective community-based study. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1361–1371. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blazer DG, Hybels SF, Pieper CF. The association of depression and mortality in elderly persons: a case for multiple, independent pathways. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2001;56:M505–M509. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.8.m505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beekman ATF, Penninx BWJH, Deeg DJH, et al. The impact of depression on the well-being, disability and use of services in older adults: a longitudinal perspective. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105:20–27. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.10078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz R, Beach SR, Ives DG, et al. Association between depression and mortality in older adults: The Cardiovascular Heart Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1761–1768. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyness JM, Moonseong H, Datto CJ, et al. Outcomes of minor and subsyndromal depression among elderly patients in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:496–504. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kivela SL, Pahkala K, Laippala P. Prevalence of depression in an elderly Finnish population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;78:101–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb06358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pahkala K, Kesti E, Kongas-Saviaro P, Laippala P, et al. Prevalence of depression in an aged population in Finland. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30:99–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00802037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma V, Copeland J, Dewey M, et al. Outcome of depressed elderly living in the community in Liverpool: a 5-year follow-up. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1329–1337. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulsant BH, Ganguli M. Epidemiology and diagnosis of depression in late life. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;S20:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sonnenberg CM, Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, et al. Sex differences in late-life depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:286–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC, et al. Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: The Cache County Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:601–607. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minicuci N, Maggi S, Pavan M, Enzi G, et al. Prevalence rate and correlates of depressive symptoms in older individuals: The Veneto Study. J Gerontol Biol Med Sci. 2002;57A:M155–M161. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.3.m155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heikkinen RL, Kauppinen M. Depressive symptoms in late life: a 10-year follow-up. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2004;38:239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet. 2005;365:1961–1970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kockler M, Heun R. Gender differences of depressive symptoms in depressed and nondepressed elderly persons. Int Journal Geriatr Psychiatr. 2002;17:65–72. doi: 10.1002/gps.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barefoot JC, Mortensen EL, Helms MJ, et al. A longitudinal study of gender differences in depressive symptoms from age 50 to 80. Psychol Aging. 2001;16:342–345. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Marwijk H, Hoeksema HL, Hermans J, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and depressive disorder in primary care patients over 65 years of age. Family Practice. 1994;11:80–84. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Smit JH, et al. Predicting the course of depression in the older population: results from a community-based study in The Netherlands. J Affect Dis. 1995;34:41–49. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)00103-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris T, Cook DG, Victor C, et al. Onset and persistence of depression in older people – results from a 2-year community follow-up study. Age Ageing. 2006;35:25–32. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoevers RA, Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, et al. The natural history of late-life depression: results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL) J Affect Dis. 2003;76:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beekman ATF, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJH, et al. The natural history of late-life depression: a 6-year prospective study in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:605–611. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoevers RA, Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, et al. Risk factors for depression in later life: results of a prospective community-based study (AMSTEL) J Affect Dis. 2000;59:127–137. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hybels CF, Pieper CF, Blazer DG. Sex differences in the relationship between subthreshold depression and mortality in a community sample of older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schoevers RA, Geerlings MI, Beekman ATF, et al. Association of depression and gender with mortality in old age. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:336–342. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.4.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, et al. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:313–321. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, et al. Hospitalization, restricted activity and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292:2115–1224. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–481. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Allen NB, et al. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 1997;12:277–287. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rantanen T, Penninx BW, Masaki K, et al. Depressed mood and body mass index as predictors of muscle strength decline in old men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:613–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, et al. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Husaini BA, Neff JA, Harrington JB, et al. Depression in rural communities: validating the CES-D scale. J Community Psychol. 1980;8:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, van Limbeek J, et al. Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community based sample of older adults in the Netherlands. Pscyhol Med. 1997;27:231–235. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lyness JM, Tamson KN, Cox C, et al. Screening for depression in elderly primary care patients. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hardin JW, HIlbe JM. Generalized Estimating Equations. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data, Release 9.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57.SAS Institute. Statistical Analysis System, Version 9.1. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, Unutzer J. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003:897–903. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Langa M, Valenstein MA, Fendrick AM, et al. Extent and cost of informal caregiving for older Americans with symptoms of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:857–863. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, et al. Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:60–67. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parashar S, Rumsfeld JS, Spertus JA, et al. Time course of depression and outcome of myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2035–2043. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.18.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grunau GL, Ratner PA, Goldner EM, et al. Is early- and late-onset depression after acute myocardial infarction associated with long-term survival in older adults? A population-based study. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:473–478. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70263-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rumsfeld JS, Jones PG, Whooley MA, et al. Depression predicts mortality and hospitalization in patients with myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005:961–967. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams LS, Ghose SS, Swindle RW. Depression and other mental health diagnoses increase mortality risk after ischemic stroke. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1090–1095. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kendler KS, Kessler RC, Neale MC, et al. The prediction of major depression in women: toward an integrated etiologic model. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1139–1148. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brown MN, Lapane KL, Luisi AF. The management of depression in older nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:69–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC. Recent care of common medical disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:284–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klap R, Unroe KT, Unutzer J. Caring for mental illness in the United States: a focus on older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:517–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Depression treatment in a sample of 1,801 depressed older adults in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:505–514. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Unutzer J, Simon G, Belin TR, et al. Care for depression in HMO patients aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;8:871–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hinton L, Zweifach M, Oishi S, et al. Gender disparities in the treatment of late-life depression: Qualitative and quantitative findings from the IMPACT trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:884–892. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000219282.32915.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Solai LK, Mulsant BH, Pollack BG. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for late-life depression: A comparative review. Drugs Aging. 2001;18:355–368. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whyte EM, Dew MA, Gildengers A, et al. Time course to response to antidepressants in late-life major depression: therapeutic implications. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:531–554. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200421080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reynolds CF, Dew MA, Pollock BG, et al. Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. New Engl J Med. 2006;354:1130–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 1999, with Health and Aging Chartbook. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1999. pp. 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 76.First MB, Spitzer RI, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition (SCID-I/Version 2.0) New York: New York State Psychiatry Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sargeant JK, Bruce ML, Florio LP, et al. Factors associated with 1-year outcome of major depression in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:519–526. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression. Critical review. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:486–492. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kuehner C. Gender differences in unipolar depression: an update of epidemiological findings and possible explanations. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;108:163–174. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Penninx BWJH, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, et al. Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau; [Accessed May 29, 2003]. Available at http://factfinder.census.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Szklo M. Population-based cohort studies. Epidemiol Rev. 1998;20:81–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]