Abstract

We examined the mother-child adjustment and child behavior problems in Arab Muslim immigrant families residing in the U.S.A. The sample of 635 mother-child dyads was comprised of mothers who emigrated from 1989 or later and had at least one early adolescent child between the ages of 11 to 15 years old who was also willing to participate. Arabic speaking research assistants collected the data from the mothers and children using established measures of maternal and child stressors, coping, and social support; maternal distress; parent-child relationship; and child behavior problems. A structural equation model (SEM) was specified a priori with 17 predicted pathways. With a few exceptions, the final SEM model was highly consistent with the proposed model and had a good fit to the data. The model accounted for 67% of the variance in child behavior problems. Child stressors, mother-child relationship, and maternal stressors were the causal variables that contributed the most to child behavior problems. The model also accounted for 27% of the variance in mother-child relationship. Child active coping, child gender, mother’s education, and maternal distress were all predictive of the mother-child relationship. Mother-child relationship also mediated the effects of maternal distress and child active coping on child behavior problems. These findings indicate that immigrant mothers contribute greatly to adolescent adjustment, both as a source of risk and protection. These findings also suggest that intervening with immigrant mothers to reduce their stress and strengthening the parent-child relationship are two important areas for promoting adolescent adjustment.

Keywords: USA, Arabs, immigration, mother-child adjustment, children, child behavior problems

Introduction

There is scant research using a comprehensive family-level approach to studying Arab Muslim immigrant mothers and adolescent children residing in Euro-American countries (Britto, 2008). Adolescence is generally considered to be complicated for these youth, in part because the typical identity issues and peer pressure associated with this age occur in the context of living in two cultures with differing normative expectations (Britto, 2008; Dwairy, 2006; Haddad & Smith, 1996; Mann, 2004; Rumbaut, 1994; Sarroub, 2005; Talbani & Hasanali, 2000). Rearing adolescents in Euro-American countries also poses demands for Arab Muslim immigrant mothers. Immigrant mothers are torn between helping their adolescents become part of a new country while also instilling values and norms from the homeland (Garcia Coll & Pachter, 2002; Haddad & Smith, 1996; Hattar-Pollara & Meleis, 1995; Kulwicki, 2008; Kwak, 2003). In addition to this more complicated aspect of parenting, immigrant mothers are also coping with their own personal stressors associated with uprooting from their homeland and resettling in a totally new and sometimes hostile environment (Abu-El-Haj, 2006; Aroian, 2006; Bacallao & Smokowski, 2007; Marvasi, 2006; Suarez-Orozco & Suarez-Orozco, 2001). Yet, not all adolescents with Arab Muslim immigrant mothers will have behavior problems.

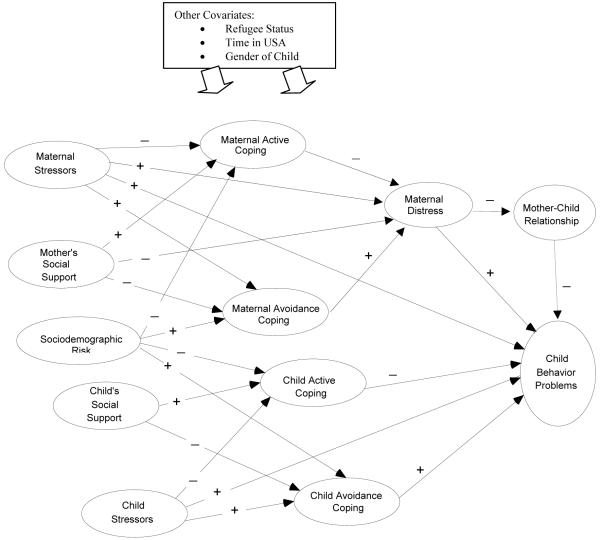

To address the dual possibility of risk and protection in Arab Muslim immigrant families, we examined the pathways in a model adapted from a study of HIV-positive mothers and their children (Hough, Brummitt, Templin, Saltz, & Mood, 2003) by which individual and family variables affect stress, coping, and adjustment in Arab mothers and their young adolescent children. The model constructs and the hypothesized relationships are shown in Figure 1. Low maternal distress and fewer child behavior problems serve as the indicators of adjustment for mothers and children, respectively. We focused on mothers rather than on both parents because Arab mothers, like those in other cultures with segmented gender roles, have greater responsibility for child rearing, even when they are carrying out the wishes of their husbands and extended family (Hattar-Pollara & Meleis, 1995; Kulwicki, 2008; Telsiz, 1998).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

Maternal Stressors, Social Support, Coping, and Psychological Distress

Immigrant women, including Arabs, are at risk for psychological distress (Aroian, 2001; Hovey, 2000; Miller & Chandler, 2002). Psychological distress among immigrants is associated with normative stressors, such as daily hassles (Franks & Faux, 1990; Hauff & Vaglum, 1995), and stressors specific to immigration, including loss of homeland, novelty, occupation, language, discrimination, and not feeling at home in the new country (Aranda, Castnaeda, Lee, & Sobel, 2001; Aroian, Norris, Patsdaughter, & Tran, 1998; Escobar, Hoyos Nervi, & Gara, 2000).

Social support and coping are important concepts that also affect psychological distress in immigrants. As in the general population, social support and distress are inversely related in immigrants (Aranda et al., 2001; Hovey, 2000; Levitt, Lane, & Levitt, 2005). Possible mechanisms for this relationship are that social support directly alleviates emotional distress and/or helps people cope, thereby limiting the emotional impact of stressors (Cohen, Underwood, &Gottlieb, 2000).

Constructive coping can also buffer the effect of stressful situations (Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood, 2003). Active rather than avoidance coping is generally considered constructive because it is more often associated with better psychological outcomes (Fondacaro & Moos, 1987; Endler & Parker, 1990; Skinner et al). A study of Mexican immigrants, for example, found that avoidance coping was related to higher levels of depression (Aranda et al., 2001). Studies of coping in other cultures, however, are limited. It is possible that certain coping strategies are effective only if they are congruent with prevailing cultural norms and values.

Parent-Child Relationship and Adolescent Behavior

Greater levels of maternal stressors and psychological distress are associated with children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Araya et al., 2008; Kao, 1999; Forehand, et al., 1991; Dubow, Edwards, & Ippolito, 1997; Dwyer, Nicholson, & Battistutta, 2003). Yet, parents can significantly reduce this risk if they are able to maintain warm, supportive parent-child relationships despite their own stressful life circumstances and emotional problems (Ahmed, 2007; Bartlett, Holditch-Davis, Belyea, Halpern, & Beeber, 2006; Gonzales, Deardorf, Formoso, Barr, & Barrera, 2006; Harker, 2001; Hill, Bush, & Rosa, 2003; Mowbray, Bybee, Oyserman, Allen-Meares, MacFarlane, & Hart-Johnson, 2004; Shek, 2005; Short & Johnston, 1997). When mothers are facing adversity, social support from significant others and constructive coping can assist them to be involved and nurturing with their children (Burchinal, Follmer, & Bryant, 1996; Voydanoff & Donnelly, 1998).

Child Stress, Coping, and Social Support

Major life change as well as daily hassles related to school, peers, and family, are associated with behavior problems in youth (Compas, 1987; Dubow, Edwards, & Ippolito, 1997). Maternal stressors and psychological distress most likely compound these more individually oriented stressors. Moreover, like adults, social support is important for adolescents. Adolescents show a wide range of adverse internalizing and externalizing behavior problems when they do not have social support (Gass, Jenkins, & Dunn, 2007; Harker, 2001; Vilhjalmsson, 1994; Zhou, 1997). Coping is also an important concept. Adolescents whose efforts to cope with daily hassles and stressful life events prove unsuccessful have greater behavior problems (Compas, 1987; Fields & Prinz, 1997). Research on avoidance coping by children and adolescents is mixed, but this type of coping is generally seen as ineffective (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001). On the other hand, studies have not investigated avoidance coping in diverse cultural contexts (Skinner, et al., 2003). Less direct ways of coping may be preferred in the Arab culture due to the high value placed on interpersonal harmony (Hodge, 2005).

Family Sociodemographic Risk and Adolescent Behavior

Resources like income, marriage, education, and employment can assist individuals and families to cope with adversity (Aroian, et al., 1998; Dorsey & Forehand, 2003; Parcel & Dufor, 2001; Santos, Bohon, & Sanchez-Sosa, 1998). Income, education, and employment may be particularly important for recent and relatively recent immigrants because of the need to reestablish themselves after leaving jobs and material possessions behind in the homeland (Jamil & Nassar-McMillan, 2007). Marriage and husband’s employment may be of even greater value for Arab immigrant mothers given cultural expectations for women to be married and not work outside the home, particularly when they are rearing children (Reed, 2004). Refugee status and less time in the US may also be risk factors: Refugees and/or more recently arrived immigrants and refugees tend to be more distressed and less able to maintain positive family relationships, most likely because of pre-migration trauma and/or post-migration resettlement demands (Aroian, Spitzer, & Bell, 1996; Jamil et al., 2002).

In summary, the literature suggests that child behavior problems is related to family socio-demographic risk as well as the mother’s psychosocial distress, which is affected by the mother’s stressors, social support, and coping. Maternal distress can diminish the quality of the mother-child relationship, which in turn affects child behavior problems. Yet, a good mother-child relationship can buffer the adverse effects of maternal stressors and distress on child behavior. The child’s own degree of stress, social support, and coping also independently affects his or her behavior problems.

Method

Sample

Use of human subjects was approved by the university affiliated with the study and in compliance with US national standards. The sample consisted of 635 dyads of Arab Muslim immigrant mothers and their adolescent children living in metropolitan Detroit, an area in the Midwestern United States. To participate, the mothers had to self-identify as Arab, have emigrated since 1989, and have at least one child between the age of 11 and 15 who was also willing to participate. The year of earliest possible emigration was originally1990 because Arab Muslim emigration to Detroit began in earnest in 1990 in response to the first Gulf war. [(Earlier waves of Arabs to the Detroit area were mostly Christians (David, 1999)]. However, the 1990 criterion was modified to 1989 because Arab Muslim families who emigrated one year earlier expressed interest in participating in the study. Reading and English ability were not criteria for study participation because data collection occurred verbally and respondents had the choice of participating in English or Arabic. The majority of mothers (97%) chose Arabic, whereas only 9.1% of the youth chose Arabic.

The sample was recruited purposively through network sampling by 12 Arabic speaking research assistants who were also Arab immigrants living and working in the local Arab community. The research assistants were purposefully selected to be representative of the countries of origin for the local study population so that recruitment from their networks would yield similar representation. The research assistants verbally advertised the study to the mothers and recruited interested participants during informal day-to-day contact with Arab Muslims. See Aroian, Katz, and Kulwicki (2006) for further details.

Data Collection and Adapting the Measures

The research assistants collected the data from January 2004 through November, 2006. Data were collected in the study participants’ homes. Consent was obtained from the mother and child and then they were physically separated in two private rooms to administer a battery of measures that were indicators of the constructs depicted in Figure 1. The mothers and youth were given $60, payable to the mother, for their time.

Table 1 lists the battery of measures and summarizes how they were operationalized as variables and indicators for the conceptual model depicted in Figure 1. Prior to administration, the measures were evaluated and modified for cultural appropriateness. First, five cultural informants who were also Arab immigrant women and social service providers in the local Arab community evaluated the measures, item by item, for cultural relevance. Their background as social service providers in the local community provided them with expertise on adolescent and family issues. Based on their recommendations, we added content about certain life circumstances that are specific to Arab Muslims and modified or deleted content that might be interpreted as potentially offensive due to local interpretations of Islam, such as items about alcohol, recreational drug use, pre- and extramarital sex, and immodesty in women and older girls. These behaviors do occur in the local Arab Muslim immigrant families but the cultural informants suggested that asking about them would alienate the community and limit their interest in participating in the study.

Table 1. Latent Constructs, Corresponding Measures and Scales, Cronbach’s Alpha (A), Factor Loadings (L), Means and Standard Deviations.

| Latent Construct | Indicator/Measure | #Items | A | L | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal Stressors | DHS (total score) | 117 | .93 | .96 | 38.98 | 17.04 |

| DIS (total score) | 23 | .86 | .93 | 1.05 | .50 | |

| 2. Child Stressors | ADHS (total score) | 30 | .80 | .87 | 7.23 | 4.41 |

| ALCES (total score) | 25 | .47 | .69 | 3.49 | 2.13 | |

| 3. Maternal Active Coping | Seeking Support & Problem solving subscales of the RWCS | 21 | .87 | .93 | 34.93 | 12.70 |

| 4. Maternal Avoidance Coping | Self-blame and Avoidance subscales of the RWCCL | 13 | .77 | .88 | 13.30 | 7.54 |

| 5. Child Active Coping | Assistance Seeking and Problem Solving subscales of the CSCY | 12 | .82 | .91 | 3.46 | 1.13 |

| 6. Child Avoidance Coping | Behavioral and Cognitive Avoidance subscales of the CSCY | 17 | .89 | .94 | 1.78 | 1.21 |

| 7. Maternal Social Support | MSPSS (total score) | 12 | .75 | .87 | 2.50 | .38 |

| 8. Child Social Support | MSPSS (total score) | 12 | .78 | .88 | 2.60 | .33 |

| 9. Maternal Distress | POMS (total score) | 58 | .93 | .96 | 33.28 | 41.25 |

| CES-D (total score) | 20 | .91 | .95 | .99 | .61 | |

| 10. Mother-Child Relationship | FPRQ subscales: | |||||

| Nurturance | 6 | .79 | .88 | 8.03 | 1.63 | |

| Mediator | 8 | .71 | .84 | 6.72 | 1.34 | |

| Togetherness | 24 | .86 | .93 | 4.57 | 1.10 | |

| 11. Child Behavior Problems | CBCL & YSR Scales: | |||||

| Internality | 63 | .90 | .95 | 20.97 | 12.21 | |

| Externality | 65 | .92 | .96 | 12.96 | 11.65 | |

| 12. Sociodemographic Risk | Sum of z scores for five sociodemographic variablesa | 5 | .68 | .82 | 50.0 | 10.0 |

Note. DHS = Daily Hassles Scale; DIS = Demands of Immigration Scale; ADHS = Adolescent Daily Hassle Scale; ALCES = Adolescent Life Change Event Scale; RWCCL = Revised Ways of Coping Checklist; CSCY = Coping Scale for Children and Youth; MSPSS = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; POMS = Profile of Mood States; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale; FPRQ = Family Peer Relationship Questionnaire; CBCL = Child Behavior Check List, YSR = Youth Self Report.

Marital status, husband’s employment, mother’s and husband’s education, and household income. Scoring and conversion to z scores are described in the text.

Next, Arabic language versions of the measures were developed through translation, back translation, and committee consensus. Translation was symmetrical, aiming at loyalty of meaning and equal familiarity in both languages (Werner & Campbell, 1970). A committee of five bilingual immigrants from the primary countries of origin for study population (i.e., Lebanon, Iraq, and Yemen) further evaluated the translation, resolving disagreement and achieving consensus before accepting the final version. Although there are different dialects of Arabic, the committee was able to reach consensus on terms that would be understandable to the local study population.

Analytic Strategy

After administering the measures to the full study sample, the measures underwent psychometric evaluation to develop the measurement model prior to testing the hypothesizd structural model (Figure 1). This was in accord with the two-stage approach recommended Anderson & Gerbing (1988) which consists of achieving an adequate measurement model in Stage 1 prior to testing the structural model in Stage). Maximum likelihood estimation was used in both stages.

Fitting the Measurement Model

In Stage 1, each measure was subjected to a second order confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to develop the measurement model for testing the structural model displayed in Figure 1. The presence of a single higher order factor or an underlying common dimension guided decisions about using subscale scores, total scale scores, or composite scores from a single or several parallel measures of the same construct. These analyses resulted in 18 scales or indicators for the 12 constructs in the SEM. Finally, a 12-factor CFA was performed on the measurement model using the variance/covariance matrix of the 18 scales. The measurement model had an acceptable fit to the data [χ2 (75, N = 635) = 236.48, p < .01; RMSEA = .06, and CFI = .95] and all factor loadings were significant (p < .05). Table 1 also summarizes the results of the measurement model (i.e., the internal consistency reliability and standardized factor loadings of the indicators) and includes the number of items and the means and standard deviations for each indicator. More details about the measurement model are provided next.

The maternal stressors construct was comprised of two indicators: The total score from the Demands of Immigration Scale (DIS; Aroian et al., 1998) and the total score from the Daily Hassles Scale (DHS; Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer & Lazarus, 1981).

The DIS measures immigration related stressors about loss, not feeling at home, novelty, occupation, language, and discrimination (Aroian et al., 1998). Respondents rated, along a 6-point scale ranging from not at all (0) to very much (5), the extent to which they had been distressed within the last 3 months by each of the stated demands. A “not applicable” option, also rated as zero, was available for those who did not have work experience outside of the home. A mean total score was calculated by summing the 23 items in the scale. A higher score indicated greater exposure to immigration related stressors. The reliability and validity of the DIS has been established with various immigrant groups, including Arabs (Aroian et al., 1998; Aroian, 2002; Aroian, Kaskiri, & Templin, 2008).

The DHS measures everyday problems with family, health, money, neighbors, work, and other areas of daily life (Kanner et al., 1981). In this study, we added a potential everyday hassle for Muslim women - religious or spiritual obligations. Although religion and spirituality are often sources of support, religious obligations can be a hassle for women when they include involve preparing special meals and entertaining guests. We also omitted an item about use of alcohol. Each hassle was measured on a 4-point scale, ranging from did not happen or was not annoying to extremely annoying. The total frequency score was calculated by summing ratings for all of the items. High scores on both measures indicate greater exposure to stressors.

The child stressors construct was comprised of two indicators: The total score from the Adolescent Daily Hassle Scale (ADHS; Seidman et al., 1995) and an abbreviated version of the Adolescent Life Change Event Scale (ALCES; Yearworth, McNamee, & Pozehl, 1992).

The ADHS assesses the intensity of daily hassles and role strains about family, peer, school, neighborhood, and resource hassles. We deleted one original item about pregnancy and added three items that capture typical hassles for Arab Muslim adolescents (e.g., teased about religious/ethnic background). The adolescent responded “yes” or “no” to whether the hassle had occurred in the past month. For each “yes” response, intensity was scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all a hassle) to 4 (a very big hassle). Intensity ratings were summed to yield a total score. A high score indicates greater exposure to daily hassles.

The ALCES contains life change events relevant to the adolescent years. We omitted items about changes resulting from dating, pregnancy, and alcohol and drug use. As previously stated, these behaviors do occur in the local Arab Muslim immigrant families but the cultural informants suggested that asking about them would alienate the community and limit their interest in participating in the study. ALCES items were summed to yield the total score. High scores indicate more life change. Although the internal consistency reliability of the ALCES we obtained was low (alpha = .47), this low reliability was offset by using the ALCES in conjunction with the more reliable ADHS to define child stressors.

Maternal social support was measured by a single indicator, the total score from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988). The MSPSS assesses perceived adequacy of support from important dimensions of people’s social lives. We substituted “husband” for “special person” and assessed support from husband, family, and friends. Scores were adjusted for mothers who did not have a spouse. The original 7-point scale ranging from very strongly disagree (1) to very strongly agree (7) was modified to 3 points. Arabs, like select other ethnic groups (Hui & Triandis, 1989; Marin & Marin, 1991), are less likely to use middle response categories when presented with this many options. The three points were coded disagree (1), neutral (4), and agree (7) to maintain comparability with prior versions of the scale. High scores indicated more social support. The revised version had excellent construct and concurrent validity (Aroian, Templin, & Ramaswamy, 2009).

The total MSPSS (Zimet et al., 1988) score was also used as single indicator of child social support, using the same rating scale and scoring as the mother’s version. Our child version (Ramaswamy, Aroian, & Templin, 2009), however, inquired about support from family, friends, and school personnel (e.g., teachers, guidance counselor). According to our cultural informants, school personnel typically augment family support to offset immigrant parents’ unfamiliarity with American norms and institutions. The revised version had excellent construct and concurrent validity (Ramaswamy et al., 2009).

Maternal active coping was a single indicator, using a composite score from totaling the Seeking Social Support and Problem Solving subscales from the Revised Ways of Coping Checklist (RWCCL; Vitaliano, Russo, Carr, Maiuro, & Becker, 1985). Mothers were asked to focus on a recent primary stressor and respond to items about coping strategies according to the degree to which the strategy was used to deal with the identified stressor. Response options ranged from never used or not applicable (0) to regularly used (3). High scores indicated more active coping. Consistent with scoring instructions, relative rather than raw scores were calculated to represent the percentage of efforts made on specific strategies and not bias scores by total number of efforts endorsed on the subscales.

Maternal avoidance coping was a single indicator, also using a composite score calculated by totaling two additional subscales from the RWCCL (Vitaliano et al., 1985), the Self Blame and Avoidance subscales. The same instructions, response options and scoring as described above for maternal active coping were used.

Child active coping was a single indicator, using a composite score calculated by totaling two of the subscales from the Coping Scale for Children and Youth (CSCY; Brodzinsky, Elias, Steiger, Simon, Gill, & Hitt, 1992), the Assistance seeking and Cognitive-behavioral problem solving subscales. Children were asked to focus on a recent primary stressor and respond to items about coping strategies according to the degree to which the strategy was used to deal with the identified stressor. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale (0 = never to 3 = very often) of the frequency of each coping behavior. High scores indicate greater active coping.

Child avoidance coping was a single indicator, also calculated as a composite score by totaling two additional subscales from the CSCY (Brodzinsky et al.1992), the Behavioral and Cognitive Avoidance subscales. The same instructions, response options and scoring described above for child active coping were used.

Mother-child relationship was comprised of three indicators, each from three subscales of the Arab Family Peer Relationship Questionnaire (A-FPRQ; Aroian, Hough, Templin, & Kaskiri, 2008), the Togetherness, Nurturance-Disclosure, and Parent as Mediator subscales. (The A-FPRQ is a modification of the original measure developed by Ellison, 1985). Both mothers and children responded to parallel versions of the A-FPRQ. Togetherness items ask about the types and frequency of activities in which parent and child engage. Nurturance-Disclosure items ask about disclosure by the child to the mother about a variety of the child’s experiences. Parent-as-Mediator items ask about the mother’s role facilitating the child’s peer relationships. The items are scored on a 1 (low frequency of a specific behavior) to 5 (high frequency) scale. Composite scores for each subscale were computed by summing mother and child responses to provide a more highly reliable, duel perspective (see Aroian, Hough et al). High scores on all three subscales indicate a more positive mother-child relationship.

Maternal distress was comprised of two indicators; total scores from the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) and total scores from the Profile of Mood States (POMS; McNair, Lorr, & Droppelman, 1981). Both of these measures have documented reliability and validity with Arabs (Aroian, Kulwicki, Kaskiri, Templin, & Wells, 2007; Ghubash et al., 2000).

The CES-D assesses the presence of depressive symptoms based upon how respondents felt during the prior week. Items were scored from 0 (rarely) to 3 (most or all of the time) with a high score reflecting increased depressive symptomatology.

The POMS is a 5-point adjective rating scale of mood disturbance, identifying Tension-Anxiety, Depression-Dejection, Anger-Hostility, Vigor-Activity, Fatigue-Inertia, and Confusion-Bewilderment. A total mood disturbance score was obtained by reverse coding the Vigor-Activity items and summing the scores across all six scales. High scores indicate greater mood disturbance.

Child behavior problems, was comprised of two indicators, one about internalizing and one about externalizing behavior problems. Mothers and children completed parallel measures; mothers completed the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 (CBCL/4-18; Achenbach, 1991a) and children completed the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991b). Both versions used a 3-point rating scale (not true (0), somewhat/sometimes true (1), or very/often true (2) now or within the last 6 months) to rate the problem items. Internalizing and externalizing behaviors included items from the Withdrawn, Somatic Complaints, and Anxious/Depressed Scales; and items from the Delinquent Behavior and Aggressive Behavior scales, respectively. High scores indicated more behavior problems. Consistent with scoring instructions (Achenbach, 1991a; 1991b), composite scores were calculated for internalizing and externalizing behavior problems by summing mother and child ratings.

Socio-demographic risk was a composite score of five variables: mother’s marital status, father’s employment, mother’s education, father’s education, and family income. Each of these variables was coded in the direction of higher risk: marital status (married = 0, else = 1), husband’s employment (full or part time = 0, else = 1), mother’s and father’s education (more than 4 year degree = 0, college graduate (4 year degree) = 1, some college = 2, high school graduation = 3, less than high school = 4, no formal education = 5), household income (1 = >60,000, 2 = 40,000-60,000, 3 = 20,000-40,000, 4 = <20,000). Each variable was standardized to a z score and summated. The total scale for the composite variable was transformed to a t score with mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. Immigrant status (0 = immigrant, 1 = refugee), length of time in the U.S., and child’s gender were also used as covariariates to test for potential confounding. Mothers provided the sociodemographic data, including data about their husbands and the child participating in the study.

Testing the Structural Model

In Stage 2, the latent variable measurement model described above was specified as a structural model according to figure 1. Modification indices were used to identify sources of misfit. After this model was fit, we used causal modeling principles as outlined in James, Mulaik, and Brett (1982) and Templin and Pieper (2003) to add additional sociodemographic covariates that might confound the structural relations.

Findings

Descriptive Results

Table 2 displays the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. The average age of the mothers reflect the fact that only women with one or more children between the ages of 11 to 15 were eligible for participation. The high number of mothers who were married and/or reported homemaker as their employment status is consistent with traditional Muslim expectations for Arab women. From .2 to 2.5% of the mothers were from countries other than Iraq, Lebanon, or Yemen. These other countries included Jordan, Kuwait, Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Palestine, Syria, the United Arab Emirates, Tunisa, and Quatar. Immigration status (immigrant, refugee, or tourist/student/work visa) was the mother’s legal status upon entry to the US. The 36.2% unemployment rate among husbands was due to disability, which was higher among men married to mothers with refugee status (21.3% vs. 3.6%, for refugees and non refugees, respectively). Presumably, disability among refugees was from pre-migration trauma, including war and/or persecution.

Table 2. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample (N =635 mothers and children).

| Variable | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Mother’s length of time U.S. (years) | 8.35 (4.17) |

| Mother’s age (years) | 44.46 (8.36) |

| Child’s age (years) | 13.81 (1.17) |

| % | |

| Child’s gender (% girls) | 49.0 |

| Mother’s marital status (% Married) | 84.9 |

| Mother’s country of origin: | |

| Iraq | 44.9 |

| Lebanon | 33.1 |

| Yemen | 11.7 |

| Other Arab country | 10.3 |

| Mother’s immigration status: | |

| Refugee | 45.3 |

| Immigrant | 47.0 |

| Tourist, student, or work visa | 7.7 |

| Mother’s education: | |

| Less than high school | 65.8 |

| College degree | 9.0 |

| Mother’s employment: | |

| Homemakers | 81.7 |

| Employed full or part time | 18.3 |

| Husband’s educationa: | |

| Less than HS | 44.1 |

| College degree | 17.9 |

| Husband’s employmenta | |

| Full time | 39.4 |

| Part time | 15.5 |

| Unemployed | 36.2 |

| Household Income < $20,000b. | 76.3 |

Percent based on mothers with husbands in the home (i.e., mothers who were not widowed, divorced, or separated n =. 545

Percent based on 510 responses.

To examine the extent of child behavior problems reported in this sample, we compared the Arab mother’s ratings of the child’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems with US normative data (Achenbach, 1991a). As can be seen in Table 3, the children in our sample had more internalizing but less externalizing behavior problems than the children in the non-clinical, normative sample. This trend was apparent for both girls and boys. Internalizing problems in Arab girls were more than ¾ of a standard deviation higher (Cohen’s d = .79) than their US counter parts. For boys this same comparison was also substantial (Cohen’s d = .69).

Table 3. Mother’s Ratings of Child Behavior Problems for Normative U.S. and Arab Immigrant (present study) Data.

| Normative U.S. Data (N=3210 scores were equally divided between clinical and nonclinical samples) | Arab Immigrant Data (n=311 girls; n=324 boys) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Sample | Nonclinical Sample | ||||||

| Scale | INT | EXT | INT | EXT | INT | EXT | |

| Girls | M | 18.3 | 20.8 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 11.32 | 5.33 |

| SD | 10.5 | 13.3 | 5.7 | 6.8 | 6.62 | 6.03 | |

| Boys | M | 14.5 | 22.9 | 6.1 | 7.8 | 9.85 | 6.93 |

| SD | 9.1 | 13.0 | 5.4 | 7.3 | 6.04 | 7.59 | |

Note: INT = Child Behavior Check List (CBCL) Internalizing scale, EXT = CBCL Externalizing scale

The Structural Model

The fit of the initial structural model (see Figure 1), although acceptable, had room for improvement. Modification indices were examined to help identify pathways to improve fit. A pathway was added from child active coping to mother child relationship. The resulting model had a better fit. All constructs had one or more significant path coefficients except for the composite variable we constructed to measure sociodemographic risk. None of the four path coefficients involving this composite variable were significant. Consequently, sociodemographic risk was removed as a composite variable from the model.

An exploratory analysis was conducted to examine whether individual sociodemographic variables that made up the composite were confounding the theoretical relations. We examined the correlation of each sociodemographic variable shown in Table 2 with each of the 18 variables used to define the model constructs (see Table 1). Education was coded as a continuous variable and sociodemographic variables with three or more categories (e.g., country of origin, immigration status, and fathers’ employment) were coded with a separate dummy variable for each category. This coding yielded 13 sociodemographic variables. To reduce the risk of Type I error, alpha was set to .003 (= .05/18), which made a correlation of .12 or larger statistically significant.

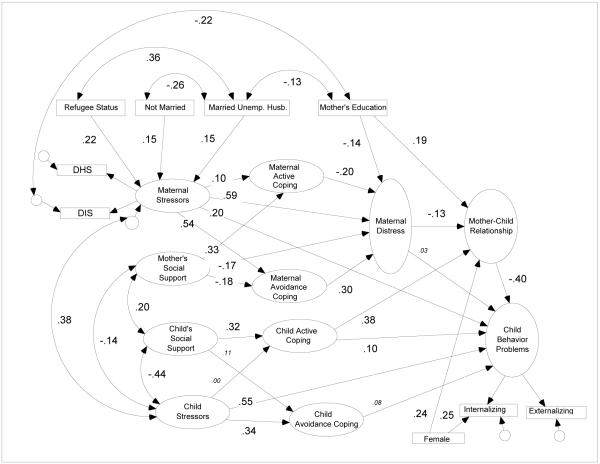

Using this criterion, 49 of the 234 possible correlations were significant. Forty of these correlations were accounted for by six sociodemographic variables, specifically refugee status, country of origin, mother’s education, father’s education, marital status, and husband’s employment. Refugee status was nearly perfectly correlated with country of origin so country of origin was dropped from further analyses. Gender and the remaining five variables (i.e., refugee status, mother’s education, marital status, husband’s employment) were added as exogenous covariates to the SEM. Father’s education was subsequently dropped because it would not fit when simultaneously added with mother’s education (mother’s and father’s education were correlated .52). Since none of the sociodemographic risk variables were correlated with coping as expected, paths from the remaining four sociodemographic variables were added to other model constructs based on an examination of modification indices and theoretical plausibility. This resulted in seven added paths (see Figure 2.). These paths depict mothers who were refugees, not married, and/or married to unemployed men as experiencing more stressors; mothers with more education as less distressed and having better mother-child relationships; and adolescent girls as having better mother-child relationships and more internalizing behavior problems.

Figure 2.

Final SEM with standardized regression coefficients. Coefficients in normal font are significant (p < .05); coefficients in small italics are not significant. Small circles with no label indicate error terms. Otherwise indicators are not shown and disturbance error terms from endogenous variables have been omitted for clarity.

The final SEM (Figure 2.) had a good fit to the data [χ2 (185, N = 635) = 536.80, p < .01; RMSEA = .06; CFI = .91] after adding one correlated error between mother’s education and the Demands of Immigration Scale. The non-significant path coefficients, four in all, are shown in Figure 2 in small italics. These include the following paths: (a) maternal distress to child behavior problems, (b) child stressors to child active coping, (c) child avoidance coping to child behavior problems, and (d) child social support to child avoidance coping. In addition, two small but significant pathways were in the wrong direction. Maternal stressors led to more rather than less maternal active coping and child active coping led to more rather than less child behavior problems. The significance of these two small and unanticipated pathways may be attributed to random error or interpreted substantively. In either case, there was clear disconfirmation of the expected pathways. Otherwise, the final model was highly consistent with proposed theory.

The model accounted for 67% of the variance in child behavior problems. Child stressors (path = .55), mother-child relationship (path = -.40), and maternal stressors (path = .20) were the causal variables that contributed the most. The model also accounted for 27% of the variance in mother-child relationship. Child active coping (path = .38), child gender (path = .24), mother’s education (path = .19), and maternal distress (path = -.13) were all predictive of the mother-child relationship. Mother-child relationship also mediated the effects of maternal distress and child active coping on child behavior problems.

Except for child active coping, which had an indirect effect on child behavior problems through mother-child relationship (p = .01), the effect of coping on behavior problems was smaller than expected. These relatively small effects of coping are in contrast to the strong predictive effects of stressors and social support on coping. For both mothers and children, social support was strongly related to active coping (paths = .33, .32, for mother and child, respectively) and stressors were strongly related to avoidance coping (paths = .54, .34, for mother and child, respectively).

Total effects were examined in order to determine the relative importance of model variables in predicting child behavior problems. Significant total effects in order of importance were child stressors (.58), mother-child relationship (-.40), maternal stressors (.23), mother’s education (.09), child avoidance coping (.08), and refugee status (.06). To further assess the adequacy of the solution, we examined distributional assumptions and re-estimated the model using the bootstrap procedure which is robust to the violation of multivariate normality assumption. The results were not altered.

Discussion

This study examined the pathways by which risk and protective variables affect behavior problems in youth with Arab Muslim immigrant mothers. Central components of the model were family socio-demographic risk; maternal and child stressors, social support, and coping; maternal distress; and quality of the mother-child relationship. Strong support was found for the proposed model. SEM procedures resulted in a good fitting model that required only a few paths to be respecified. Almost all of the proposed paths were statistically significant and in the expected direction. The final model accounted for 67% of the variance in child behavior problems, with child stressors contributing the most, followed by the mother-child relationship and maternal stressors. Compared to normative data, the children in our study were reported to have significantly more internalizing problem behaviors but less externalizing problem behaviors than those obtained in a nonclinical sample. The ratings of internalizing problem behaviors in the adolescents in our study, however, were far from being in the clinical range. Reports of less externalizing behavior problems are consistent with traditional Arab Muslim expectations for adolescent conformity and obedience to parents (Dwairy, 2006). When conformity is the norm, poor adjustment is often manifested through internalizing behavior problems like withdrawal, somatic complaints, depression, and anxiety (Lambert Weisz, & Knight, 1989).

Immigrant mothers contributed greatly to adolescent adjustment, both as a source of risk and protection. Maternal stressors were a major risk factor, contributing to child behavior problems directly as well as indirectly through maternal distress and its negative effect on the mother-child relationship. Unmarried mothers, mothers with unemployed husbands, and mothers who were refugees had the most stressors. Conversely, a good mother-child relationship was protective, contributing to fewer child behavior problems. Mothers who were more highly educated had better mother-child relationships. Adolescents who used more active coping and adolescent girls also had better mother-child relationships. The finding that girls had better mother-child relationships is consistent with the literature about Arab families (Quafisheh, 2003).

Maternal and child social support were also important, both leading indirectly to a better mother-child relationship. Maternal social support led to a better mother-child relationship by decreasing maternal distress through her use of more active coping and less avoidance coping. Similarly, child social support led to a better mother-child relationship through its effects on child active coping: Adolescents with more social support were more likely to use active coping and, in turn, these adolescents were more likely to have a better mother-child relationship. The proposed negative path between child social support and child avoidance coping, on the other hand, was not statistically significant.

The greatest discrepancy between the hypothesized and the final model pertained to paths that involved coping. In addition to the insignificant path between child social support and child avoidance coping, two other proposed paths involving child coping were insignificant. One of these insignificant paths was between child stressors and child active coping and the other was between child avoidance coping and child behavior problems. A significant path involving child coping was in the wrong direction: Child active coping led to significantly more, rather than less child behavior problems. The path from child active coping to mother-child relationship was not proposed but added to improve the model fit. Lastly, the path from maternal stressors to maternal active coping was in the wrong direction; we expected more stressors to lead to less rather than more active coping.

Two of these unexpected findings about coping are theoretically plausible. First, we anticipated that greater maternal stress would overwhelm coping capacities and lead to less active coping. Yet, it makes intuitive sense that people use more coping when they experience greater stress, regardless of whether the coping is active or avoidant. Perhaps our initial hypothesis oversimplified the distinction between active and avoidance coping by casting them as mutually exclusive. In reality, coping is a complex dynamic process with people using both types of coping in nearly every coping episode (Skinner, et al., 2003). The positive path from child active coping to the mother-child relationship also has a basis in the literature. According to a number of studies, there is a positive association between a good parent-child relationship and the child’s ability to cope successfully with stressful situations (Gentzler, Contreras-Grau, Kerns, & Weimer, 2005; Kliewer, Fearnow, & Miller, 1996; Stern & Zevon, 1990; Valiente, Fabas, Eisenberg, & Spinrad, 2004). Although Gottman, Katz, and Hooven, (1997) suggest that this association is because good parents coach their children to cope with stressful situations, Gentzler and colleagues contend that this unidirectional portrayal of parents influencing children is too simplistic for adolescents. Adolescents who actively cope by seeking help and support from their mothers are, in all likelihood, easier and more rewarding to parent.

Explanations for the other study findings about coping are more tentative. Child active coping may be problematic for Arab youth when it occurs independently of parents. The Arab cultural expectation for youth to respect parental authority (Dwairy, 2006) may be at odds with autonomous coping. This explanation is consistent with our finding that child active coping only leads to less behavior problems indirectly, though the mother-child relationship. It is also noteworthy that the children in our study were young adolescents, ranging in age from 11 to 15 years old. Developmentally, they may not have accrued the skills to actively cope independent of parents. Active coping can be demoralizing and frustrating, resulting in more behavior problems, when it is beyond the child’s skill level (Power, 2004). The insignificance of avoidance coping on child behavior problems may be because the concept is overly broad, not distinguishing between various forms or functions of avoidance. Some avoidance strategies may be effective if they defuse the situation and do not lead to increased interpersonal conflict or a recurrence of the problem. In fact, avoidance may be the best coping approach for Arab children because of the cultural value for interpersonal harmony (Hodge, 2005).

The life circumstances of the mothers in our study who were refugees most likely account for why refugee status was associated with greater levels of maternal stressors, maternal distress, and spousal unemployment. Almost all of the refugees in our study were Iraqi Shiites. Refugees from Iraq have lived through various war time traumas, first from the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980’s, followed by the 1990 and present Persian Gulf wars. During the 1990 Gulf war, the Saddam Hussein regime brutally persecuted Shiites by revenge killings, rape, and torture (Wallbridge & Aziz, 2000).

The model we tested with Arab Muslim immigrant mothers and their adolescent children was an adaptation of a model used previously with African American HIV-positive mothers and their school aged children (Hough et al, 2003). There were a number of similar findings in both studies. The most notable differences in the two studies pertained to the differential effects of child social support and mother-child relationship on child behavior problems. In school aged African American children of HIV-positive mothers but not in Arab Muslim adolescents, level of social support from others had a direct, positive relationship to child behavior problems. Conversely, the parent-child relationship had no significant effect on the adjustment of the children of African American HIV positive mothers, whereas a significant direct effect was observed in Arab adolescents. Although younger in age, it appears that children of African American HIV positive mothers experience a more salutary effect of social support from a variety of sources but are less impacted by a positive parent child relationship than the older, Arab children in this study. Most likely, the importance of the mother-child relationship in our study sample of Arab Muslim immigrant families reflects Arab cultural values about women’s roles as mothers caring for children (Corolan, Bagherinia, Juhari, Himelright, & Mouton-Sanders, 2000; Kulwicki, 2008). Consistent with these expectations, most of the mothers participating in our study described themselves as homemakers or full time mothers (81.7%). Another expected role for Arab Muslim mothers is to protect family honor by ensuring that children follow Islamic codes of behavior (Carolan et al., 2000; Kulwicki, 2008). Two of the three components of the mother-child relationship we measured - - Togetherness or the type and frequency of activities the parent and child engage in together and Parent as Mediator or the extent to which the parent encourages or aids the child in maintaining peer relations - - have been noted in the literature as strategies for Arab mothers to protect family honor. Specifically, Arab Muslim mothers promote adherence to Islamic rules about proper behavior by engaging in activities together with their adolescents and mediating peer relationships by socializing with other Arab Muslim families with adolescents who share similar norms and values (Haddad & Smith, 1996; Hattar-Pollara & Meleis, 1995).

There are several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings of our study. First, we did not randomly select study participants. Instead, we used purposive network sampling by employing research assistants who were representative of the local Arab immigrant community to recruit the sample (Aroian, et al., 2006). Information about this community suggests that we obtained a representative sample with regard to the country of origin of the local study population but not with regard to socioeconomic status (Arab American Institute, 2008). The financial incentive for study participation most likely prompted low income and less educated families to participate. Unfortunately, however, we do not have socio-demographic data about families who refused participation. Another potential bias is that mother-child dyads were recruited through the mothers, many of whom had more than one child eligible to participate. We have no way of knowing if the incidence of behavior problems we obtained can be generalized to other adolescents with Arab Muslim immigrant mothers. Mothers may have selected children with behavior problems in the hope of obtaining help. On the other hand, mothers may have selected children who were more willing to comply with the invitation to participate. Children in this latter case are unlikely to have externalizing behavior problems. Another limitation is that the information we obtained omitted the father’s point of view. Lastly, all data were collected concurrently and caution must be taken in assigning a predictive interpretation to the study findings. Thus, our recommendations for future research are to include fathers and randomly select the child participants from the pool of all eligible children in the household. Longitudinal studies are also needed to investigate the role of parent child relationships over time and for older children.

Despite limitations, our findings provide direction for addressing behavior problems in young adolescents with Arab Muslim immigrant mothers. Mothers who are refugees, are single, have unemployed husbands, and have low education are at higher risk. They as well as their children are in need of extra attention. We suggest a multi-prong approach that targets the stressors experienced individually by mothers and children, assists mothers to cope effectively with their distress, and strengthens the mother-child relationship.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the United States National Institutes of Health National Institute of Nursing Research, R01NR 008504, Karen Aroian, Principal Investigator

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Edythe s Hough, Wayne State University

Thomas N Templin, Wayne State University

Anahid Kulwicki, Florida International University

Vidya Ramaswamy, Wayne State University

Anne Katz, Wayne State University.

References

- Abu TR. Race, politics, and Arab American youth: Shifting frameworks for conceptualizing educational equity. Educational Policy. 2006;20(1):13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SR. Perceived racism, psychological and behavioral functioning: Culturally relevant moderators in Arab American adolescents. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2007;68(4B):2634. Doctoral Dissertation, Wayne State University, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step active. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Arab American Institute Michigan demographics. 2008 http://www.aaiusa.org/arab-americans/22/demographics.

- Aranda MP, Castaneda PL, Sobel E. Stress, social support, and coping as predictors of depressive symptoms: Gender differences among Mexican Americans. Social Work Research. 2001;25(1):37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Araya R, Hu K, Heron J, Enoch MA, Evans J, Lewis G, Nutt D, Goldman D. Effects of stressful life events, maternal depression, and 5-HTTLPR genotype on emotional symptoms in pre-adolescent children. American Journal Medical Genetics. 2008 Nov 14; doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30888. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ. Immigrant women’s health. Annual Review of Nursing Research. 2001;19:179–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ. Children of foreign-born parents. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing. 2006;44(10):15–18. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20061001-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ, Hough ES, Templin TN, Kaskiri EA. Development and Psychometric Evaluation of an Arab Version of the Family Peer Relationship Questionnaire. Research in Nursing and Health. 2008 doi: 10.1002/nur.20277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ, Kaskiri EA, Templin TN. Psychometric evaluation of the Arabic language version of the Demand of Immigration Scale. International Journal of Testing. 2008;8(1):2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ, Katz A, Kulwicki A. Recruiting and retaining Arab Muslim mothers and children for research. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(3):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ, Kulwicki A, Kaskiri E, Templin TN, Wells C. Psychometric evaluation of the Arabic language version of the Profile of Mood States. Research in Nursing and Health. 2007;30:531–541. doi: 10.1002/nur.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ, Norris A, Patsdaughter CA, Tran TV. Predicting psychological distress among former Soviet immigrants. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1998;44(2):284–294. doi: 10.1177/002076409804400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ, Spitzer A, Bell M. Family support and conflict among former Soviet immigrants. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1996;18(6):655–674. doi: 10.1177/019394599601800604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ, Templin TN, Ramaswamy V. Adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support for Arab immigrant women. Health Care for Women International. doi: 10.1080/07399330903052145. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aswad B, Gray NA. Challenges to the Arab-American family and ACCESS. In: Aswad B, Bilge B, editors. Family and gender among American Muslims: Issues facing Middle Eastern and immigrants and their descendants. Temple University Press; Philadelphia: 1986. pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bacallao ML, Smokowski PR. The costs of getting ahead: Mexican family system changes after immigration. Family Relations. 2007;56:52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett R, Holditch-Davis D, Belyea M, Halpern CT, Beeber L. Risk and protection in the development of problem behaviors in adolescents. Research in Nursing & Health. 2006;29:607–621. doi: 10.1002/nur.20163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto PR. Who am I? Ethnic identity formation of Arab Muslim children in contemporary U.S. society. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(8):853–857. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799fa6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky DM, Elias MJ, Steiger C, Simon J, Gill M, Hitt JC. Coping Scale for Children and Youth: Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1992;13:195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Follmer A, Bryant DM. The relations of maternal social support and family structure with maternal responsiveness and child outcomes among African-American families. Developmental Psychology. 1996;33:1000–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Carolan M,T, Bagherinia G, Juhari R, Himelright J, Mouton-Sanders M. Contemporary Muslim families: Research and practice. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2000;22(1):67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH. Social Relationships and Health. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social support, measurement and intervention. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2000. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101(3):393–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(1):87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David G. The Mosaic of Middle Eastern Communities in Metropolitan Detroit. United Way Community Services; Detroit: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Forehand R. The relation of social capital to child psychological adjustment difficulties: The role of positive parenting and neighborhood dangerousness. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2003;25:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Edwards S, Ippolito MF. Life stressors, neighborhood disadvantage, and resources: A focus on inner-city children’s adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26(2):130–44. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2602_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwairy M. Counseling and psychotherapy with Arabs and Muslims. Teachers College Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer SB, Nicholson JM, Battistutta D. Population level assessment of the family risk factors related to onset or persistence of children’s mental health problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:699–711. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison ES. A multidimensional, dual-perspective index of parental support. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1985;7:401–24. doi: 10.1177/019394598500700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler NS, Parker JDA. Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:844–854. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.5.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar JI, Hoyos Nervi C, Gara MA. Immigration and mental health: Mexican Americans in the United States. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2000;8:64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields L, Prinz RJ. Coping and adjustment during childhood and adolescence. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;17(8):937–976. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fondacaro MR, Moos RH. Social support and coping: A longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1987;15(5):653–673. doi: 10.1007/BF00929917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Wierson M, Thomas AM, Armistead L, Kempton T, Neighbors B. The role of family stressors and parent relationships on adolescent functioning. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30(2):316–22. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199103000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks F, Faux SA. Depression, stress, mastery and social resources in four ethnocultural women’s groups. Research in Nursing and Health. 1990;13(3):283–292. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Pachter LM. Ethnic and minority parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting (2nd Ed.) Volume 4: Social Conditions and Applied Parenting. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, New Jersey: 2002. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N, Rutter M. Coping Scale for Children and Youth: Scale Development and Validation. Stress, coping, and development in children. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gass K, Jenkins J, Dunn J. Are sibling relationships protective? A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):167–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentzler AL, Contreras-Grau JM, Kerns KA, Weimer BL. Parent-child emotional communication and children’s coping in middle childhood. Social Development. 2005;14(4):591–612. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Deardorf J, Formoso D, Barr A, Barrera M. Family mediators of the relation between acculturation and adolescent mental health. Family Relations. 2006;55:318–330. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ghubash R, Daradkeh TK, Al-Naseri KS, Al-Bloushi NB, Al-Daheri AM. The performance of the Center for Epidemiologic Study DepressionScale (CES-D) in an Arab female community. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2000;46(4):241–249. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad YY, Smith JI. Islamic values among American Muslims. In: Aswad B, Bilge B, editors. Family and gender among American Muslims: Issues facing Middle Eastern and immigrants and their descendants. Temple University Press; Philadelphia: 1996. pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Harker K. Immigrant generation, assimilation, and adolescent psychological well-being. Social Forces. 2001;79(3):969–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Hattar-Pollara M, Meleis AI. Parenting their adolescents: The experiences of Jordanian immigrant women in California. Health Care for Women International. 1995;16:195–211. doi: 10.1080/07399339509516171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauff E, Vaglum P. Organised violence and the stress of exile: Predictors of mental health in a community cohort of Vietnamese refugees three years after resettlement. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;166(3):360–367. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR, Roosa MW. Parenting and family socialization strategies and children’s mental health: Low income Mexican-American and Euro-American mothers and children. Child Development. 2003;74:189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge DR. Social work and the house of Islam: Orienting practitioners to the beliefs and values of Muslims in the U.S. Social Work. 2005;50(2):162–173. doi: 10.1093/sw/50.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough ES, Brumitt G, Templin T, Saltz D, Mood D. A model of mother-child coping and adjustment to HIV. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:643–655. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey J. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2000;6(2):134–151. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui CH, Triandis HC. Effects of culture and response format on extreme response style. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1989;20:296–309. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil H, Hakim-Larson J, Farrag M, Kafaji T, Duqum I, Jamil LH. A retrospective study of Arab American mental health clients: Trauma and the Iraqi refugees. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72(3):355–361. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil H, Nassar-McMillan S. Immigration and attendant psychological sequelae: A comparison of three waves of Iraqi immigrants. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(2):199–205. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner AD, Coyne JC, Schaefer C, Lazarus RS. Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1981;4(1):1–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00844845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao G. Psychological well-being and educational achievement among immigrant youth, in children of immigrants. In: Hernandez DJ, editor. Health, Adjustment, and Public Assistance. National Academy Press; Washington, D. C: 1999. pp. 410–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Fearnow MD, Miller PA. Coping socialization in middle childhood: Tests of maternal and paternal influences. Child Development. 1996;67:2339–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulwicki A. People of Arab Heritage. In: Purnell L, Paulanka B, editors. Transcultural health care: A culturally competent approach. F. A. Davis; Philadelphia: 2008. pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak K. Adolescents and their parents: A review of intergenerational family relations for immigrant and non-immigrant families. Human Development. 2003;46:115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MC, Weisz JR, Knight F. Over- and undercontrolled clinic referral problems of Jamaican and American children and adolescents: The culture general and the culture specific. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57(4):467–72. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt MJ, Lane JD, Levitt J. Immigration stress, social support and adjustment in the first postmigration year: An intergenerational analysis. Research in Human Development. 2005;2(4):159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Mann M. Immigrant parents and their emigrant adolescents: The tension of inner and outer worlds. American Journal of Psychoanalysis. 2004;64(2):143–153. doi: 10.1023/B:TAJP.0000027269.37516.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Marin BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Marvasti A. Being Middle Eastern American: Identity negotiation in the context of the war on terror. Symbolic Interaction. 2006;28(4):525–547. [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppelman LF. Manual for the profile of mood states. Educational and Industrial Testing Service; San Diego: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, Chandler PJ. Acculturation, resilience, and depression in midlife women from the former Soviet Union. Nursing Research. 2002;51:26–32. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray CT, Bybee D, Oyserman D, Allen-Meares P, MacFarlane P, Hart-Johnson T. Diversity of outcomes among adolescent children of mothers with mental illness. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2004;12(4):206–221. [Google Scholar]

- Parcel TL, Dufor MJ. Capital at home and school: Effects on child social adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Patten CA, Gillin JC, Farkas AJ, Gilpin EA, Berry CC, Pierce JP. Depressive symptoms in California adolescents: Family structure and parental support. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;20:271–278. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00170-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TG. Stress and coping in childhood: The parents’ role. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4(4):271–317. [Google Scholar]

- Qafisheh S. The mother-daughter relationship in Arab-American families. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2003;63(8B):3979. Doctoral dissertation, Alliant International University. [Google Scholar]

- Read JG. Family, religion, and work among Arab American women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2004;66:1042–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy V, Aroian KJ, Templin TN. Adaptation and Psychometric Evaluation of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support for Arab American Adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos SJ, Bohon LM, Sanchez-Sosa JJ. Childhood family relationships, marital and work conflict, and mental health distress in Mexican immigrants. Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26(5):491–508. [Google Scholar]

- Sarroub L. All American Yemeni Girls. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schopmeyer KA. Demographic Portrait of Arab Detroit. In: Abraham N, Shryock A, editors. Arab Detroit from Margin to Mainstream. Wayne State University Press; Detroit: 2000. pp. 61–92. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman E, Allen L, Aber JL, Mitchell C, Feinman G, Yoshikawa H, Comtois KA, Golz J, Miller RL, Ortiz-Torres B, Roper GC. Development and validation of adolescent-perceived microsystem scales: Social support, daily hassles, and involvement. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23(3):355–369. doi: 10.1007/BF02506949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek DTL. A longitudinal study of perceived family functioning and adolescent adjustment in Chinese adolescents with economic disadvantage. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26(4):518–543. [Google Scholar]

- Short KH, Johnston C. Stress, maternal distress, and children’s adjustment following immigration: The buffering role of social support. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(3):494–503. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the Structure of Coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(2):216–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern M, Zevon MA. Stress, coping, and family environment: The adolescent’s response to naturally occurring stressors. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1990;5:290–305. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Orozco C, Suarez-Orozco M. Children of Immigration. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- James LR, Mulaik SA, Brett JM. Causal Analysis: Assumptions, Models, and Data. Sage; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Talbani A, Hasanali P. Adolescent females between tradition and modernity: Gender role socialization in South Asian immigrant culture. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23:615–627. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telsiz M. Adolescents’ views on the parental role: A Turkish study. International Journal of Sociology of the Family. 1998;28:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Templin T, Pieper B. Causal Modeling in WOC. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing. 2003;30(4):168–173. doi: 10.1067/mjw.2003.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Fabas RA, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL. The relations of parental expressivity and support to children’s coping with daily stress. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(1):97–106. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilhjalmsson R. Effects of social support on self-assessed health in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23:437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Russo J, Carr JE, Maiuro RD, Becker J. The Ways of Coping Checklist: Revision and psychometric properties. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1985;20:3–26. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2001_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff P, Donnelly BW. Parents’ risk and protective factors as prediction of parental well-being and behavior. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1998;60:344–355. [Google Scholar]

- Wallbridge LS, Aziz TM. After Karbala: Iraqi refugees in Detroit. In: Abraham N, Shryock A, editors. Arab Detroit from Margin to Mainstream. Wayne State University Press; Detroit: 2000. pp. 321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Werner O, Campbell DT. Translating, working through interpreters, and the problem of decentering. In: Naroll R, Cohen R, editors. A handbook of method in cultural anthropology. The Natural History Press; New York: 1970. pp. 398–420. [Google Scholar]

- Yearworth RC, McNamee JJ, Pozehl B. The adolescent life change event scale: Its development and use. Adolescence. 1992;27(108):783–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Growing up American: The challenge confronting immigrant children and children of immigrants. Annual Review of Sociology. 1997;23:63–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zogby J. Detroit Metropolican Statistical Area Census Report. Arab American Institute; Washington, D.C.: 1998. p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Zweig JM, Phillips SD, Duberstein Lindberg L. Predicting adolescent profiles of risk: Looking beyond demographics. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:343–353. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]