Abstract

Highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza viruses that are currently circulating in southeast Asia may acquire the potential to cause the next influenza pandemic. A number of alternate approaches are being pursued to generate cross-protective, dose-sparing, safe, and effective vaccines, as traditional vaccine approaches, i.e., embryonated egg-grown, are not immunogenic. We developed a replication-incompetent adenoviral vector-based, adjuvant-and egg-independent pandemic influenza vaccine strategy as a potential alternative to conventional egg-derived vaccines. In this paper, we address suboptimal dose and longevity of vaccine-induced protective immunity and demonstrate that a vaccine dose as little as 1 × 106 plaque-forming unit (PFU) is sufficient to induce protective immune responses against a highly pathogenic H5N1 virus. Furthermore, the vaccine-induced humoral and cellular immune responses and protective immunity persisted at least for a year.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses, A/H5N1, first emerged in 1997 in Hong Kong, with 18 documented cases, including six deaths.1,2 These viruses, transmitted directly from the infected poultry to humans in Hong Kong, have since been detected in wild birds and poultry in over 60 countries.3 This increased spread of the disease in birds has led to more than 300 human cases, with a staggering 60% case fatality rate mostly in southeast Asia.4 Migrating birds are suspected to have spread the virus as far west as eastern Europe and Africa.5,6 Most documented human cases have a direct association with infected birds, although limited human-to-human transmission has occurred.7,8 Moreover, the culling of infected flocks in most countries has controlled the spread of the disease. As the H5N1 viruses have evolved, they have been categorized into genetically and antigenically distinct clades; clade 1 viruses have been isolated from Vietnam and Thailand and clade 2 from Indonesia, Turkey, and other countries.9–11 However, since 2005, clade 2 human viruses have been further divided into three distinct subclades, widening the range for optimal vaccine coverage.

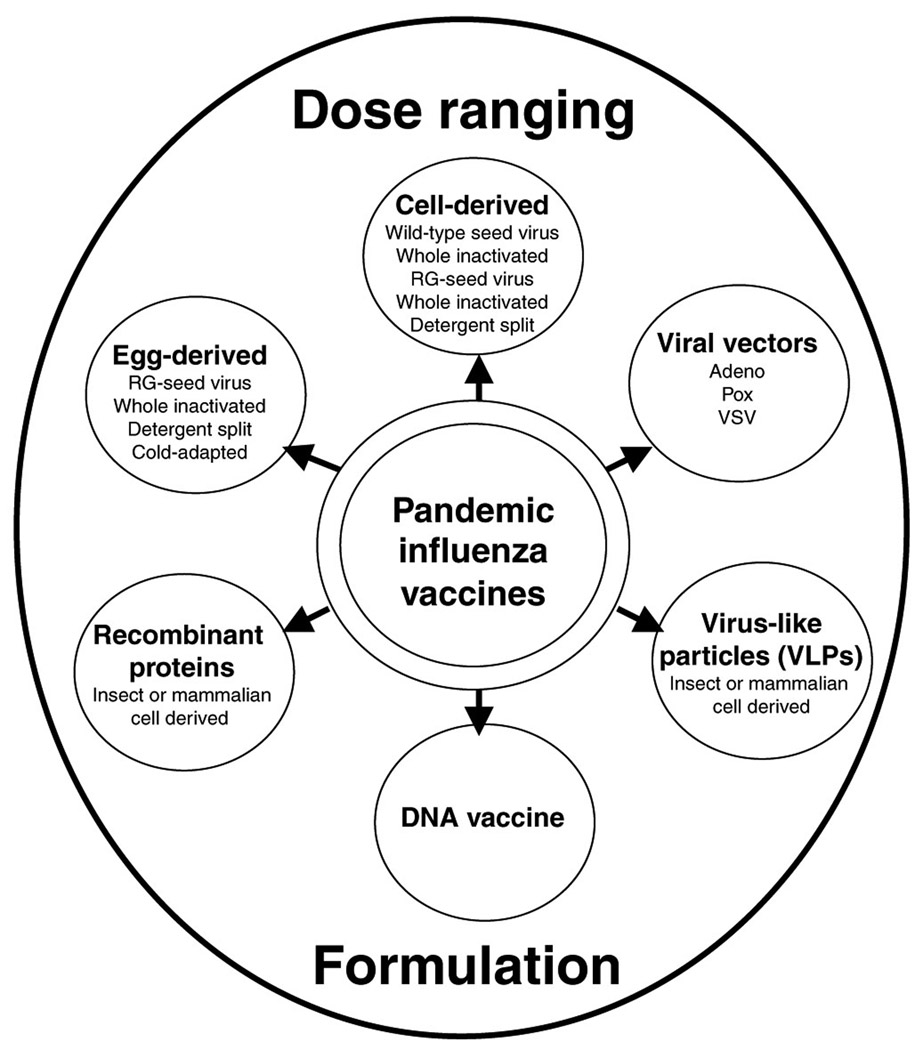

The vaccine strategy during the inter-pandemic period is to prime the populations with a vaccine that offers some cross-protection against the pandemic virus until a “perfect match” pandemic vaccine can be made. However, the manufacture of pre-pandemic or pandemic vaccines by traditional methods, i.e., embryonated chicken egg-grown, may take up to 6 months. In addition, these traditional influenza vaccines are not very immunogenic and require heightened biosafety facilities and billions of embryonated eggs to manufacture enough vaccine doses to immunize high-risk individuals worldwide. Baculovirus-derived recombinant hemagglutinin (HA) protein from H5N1 viruses eliminates the need for the egg and biosafety requirements, but is not cost-effective and also has been shown to be poorly immunogenic (Figure 1).12 An alternative approach to generate an H5N1 vaccine seed virus without a need for high containment manufacturing facilities became possible with the advent of reverse genetics technology13–16 and the observation that the deletion of multibasic amino-acid cleavage site on the HA molecule did not affect antigenicity. Thus, the generation of candidate H5N1 vaccine strains, by reverse genetics, containing the modified HA and wild-type neuraminidase from the H5N1 virus and the remaining six genes from A/PuertoRico/8/34 became possible, and it was the first US Food and Drug Administration-approved egg-grown H5N1 reassortant vaccine.17 This development has also facilitated generation of the cold-adapted virus vaccine (Figure 1), where a seasonal influenza virus, A/Ann Arbor/6/60, containing the modified HA and neuraminidase genes from an H5N1 virus is attenuated to enable limited replication, specifically in the upper airway and nasal passages.18 However, these approaches still rely on an uninterrupted supply of embryonated eggs. As avian influenza viruses are highly lethal to chicken, ensuring the availability of embryonated eggs for vaccine production poses a major challenge. It should be noted that the current worldwide egg-grown influenza vaccine-manufacturing capacity operating at full capacity would also not be able to meet the demand.19 To address these issues, dose-sparing strategies are being investigated to reduce the amount of antigen required to generate a robust immune response by the inclusion of adjuvants.20,21 Alternative egg-independent vaccine strategies outlined in Figure 1 are also being developed with a high degree of success in preclinical and clinical studies, namely mammalian cell-derived vaccines, viral vectors, recombinant proteins, virus-like particles, DNA vaccines, and passive immunization with a cocktail of monoclonal antibodies.11,22–26

Figure 1. Preventive vaccination strategies for pandemic preparedness.

In preparation for a pandemic, a number of vaccine approaches are currently being investigated in preclinical and clinical trials, where each approach is depicted in one of the six circles surrounding the core, described here as pandemic influenza vaccines. Other factors affecting the outcome of a successful vaccine are range of dose, including dose-limiting strategies and immunization schedule, and formulation, with adjuvants or other immunostimulatory compounds, in efforts to meet the preferred profile for an effective vaccine. RG, reverse genetics. VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus.

The preferred profile for an effective pandemic vaccine should be safe and effective for all populations and health status, immunogenic preferably at low doses and with one administration, easily and inexpensively manufactured, effective against variant pandemic influenza viruses, induce both humoral and cellular immune responses, thermostable, and have a shelf life of over a year. As unadjuvanted vaccines do not meet many of these characteristics, the addition of adjuvants and adjuvant-independent strategies are being pursued.20 Our group and others have developed a replication-deficient human adenoviral vector 5 (HAd) approach as a pandemic vaccine strategy.27,28 This vector approach has been used as a safe and effective vaccine strategy in preclinical and clinical studies for a number of infectious diseases, including human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, measles, rabies, anthrax, Ebola, severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus, and several forms of cancers. Furthermore, the Ad-vector approach has been shown to have an excellent safety profile in clinical trials.40–42 This strategy eliminates the need for embryonated eggs required for virus growth, as well as the need for enhanced biosafety level 3 laboratories. The HAd vector can be grown to high titers in qualified cell lines in a short period of time and can overcome glycosylation issues, leading to better immunogenicity. Immunization by parenteral or mucosal routes leads to foreign gene expression without insertion of the HAd genome into the host’s genome. Furthermore, the HAd vector engages the innate immune response by both Toll-like receptor-dependent and Toll-like receptor-independent pathways by targeting dendritic cells and macrophages, thus not requiring an adjuvant to engage both arms of the immune response.43 As the HAd-vector delivery approach generates both humoral and cell-mediated immunity against the target disease, using this approach to generate an effective pandemic vaccine is a logical alternative to traditional egg-derived vaccines.

Previously, we have shown 100% protection against lethal challenge with antigenically distinct strains of H5N1 viruses in mice immunized with HAd expressing the HA gene from A/Hong Kong/156/97 (HAd-H5HA) in the absence of detectable neutralizing and hemagglutinating antibodies against A/Vietnam/1203/04. This vaccine generated humoral immune responses against an antigenically similar virus, as well as CD8 þ T-cell responses against the conserved HA518 epitope, which is conserved in nearly all human H5N1 viruses isolated since 1997, including human viruses isolated in 2007 (C. Smith, personal communication). These findings indicate that HAd-based pre-pandemic vaccine confers broader protection and offers a stockpiling option.

An ideal pre-pandemic or pandemic influenza vaccine should possess the ability to generate robust, long-lasting protective immune responses with a small amount of antigen to meet the global demand. In this paper, we assess the immune responses to the HAd-H5HA vaccine using a suboptimal dose immunization strategy and show that protection against challenge with an antigenically similar virus was provided by low doses of the vaccine even in the absence of detectable antibodies. We also demonstrate that the vaccine induced long-lasting protective humoral and cell-mediated immune responses for at least 12 months post-immunization. Our findings clearly indicate that the egg-and adjuvant-independent Ad-vector-based pandemic influenza vaccine strategy confers protection against antigenically distinct strains, generates long-lasting protective immunity, and is a viable alternative to the traditional egg-derived vaccines.

RESULTS

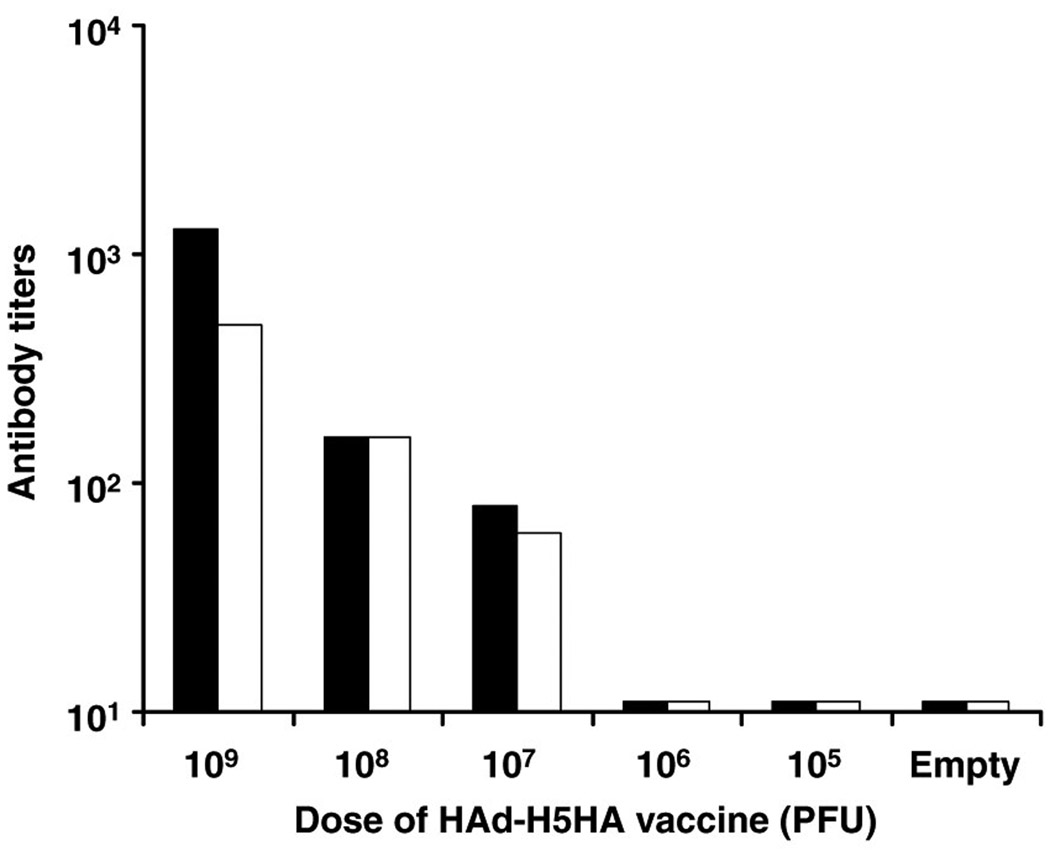

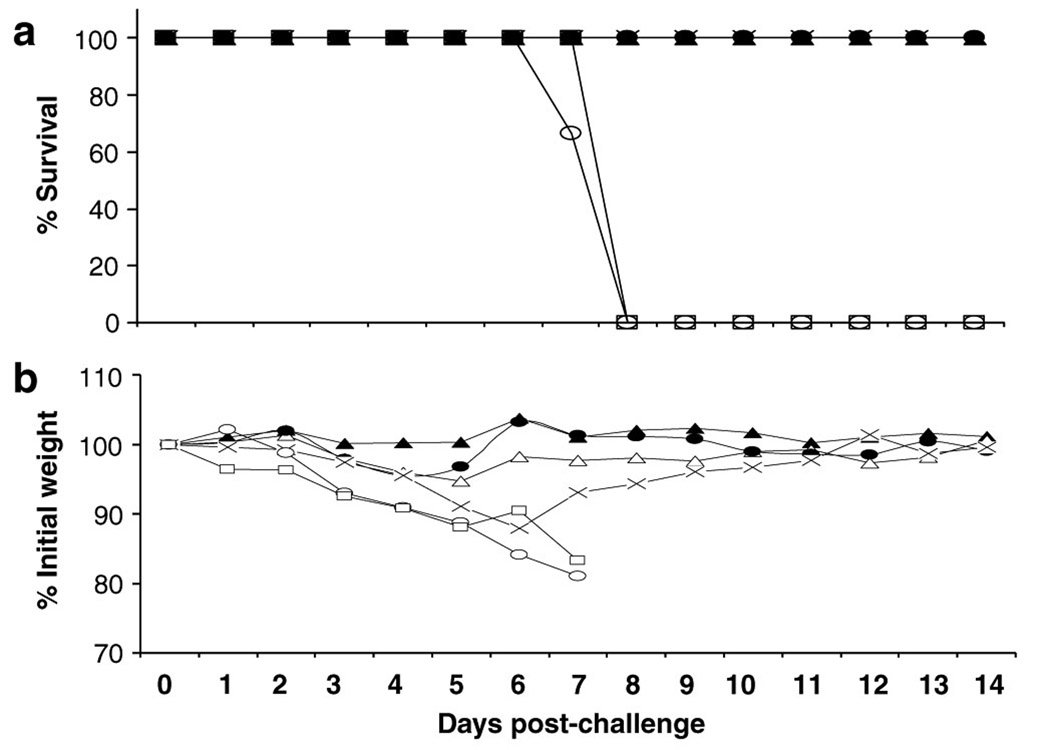

We previously reported that 108 plaque-forming unit (PFU) of HAd-H5HA vaccine was the optimal dose for the induction of protective antibody responses as determined by hemagglutination inhibition (HI) test.27 Neutralizing antibodies induced by the vaccine mirrored the HI antibody titers as seen in Figure 2, where the neutralizing antibody titers induced by the vaccine at doses of 109, 108, and 107 PFU20 are 1,280, 160, and 80, respectively, which are indicative of 0 protective titers. However, at 106 and 105 PFU vaccine doses, no detectable serological responses were observed. Nevertheless, when these mice were challenged with a lethal dose of an antigenically similar virus A/Hong Kong/483/1997 (HK/483), all groups of mice were protected against death with the exception of groups that received either a vaccine dose of 105 PFU or an empty vector (Figure 3a). However, mice immunized with a vaccine dose of 106 PFU did show morbidity, with a weight loss of 12% on day 6 before fully recovering, whereas mice immunized with vaccine at >106 PFU doses exhibited little to no weight loss (Figure 3b). We have previously shown that HAd-H5HA vaccine induces CD8+ T-cell responses and confers protection against death even in the absence of neutralizing antibody responses against an antigenically distinct A/VN/1203/04 virus.27 Hence, the protection conferred by the vaccine at 106 PFU dose may be due to CD8+ T cells and/or nonneutralizing antibodies through an antibody-dependent cellmediated cytotoxicity mechanism.

Figure 2. HAd-H5HA vaccine induces neutralizing antibody and HI titers in a dose-dependent manner.

BALB/c mice were immunized i.m. with varying doses of HAd-H5HA vaccine starting from 109 PFU twice 4 weeks apart as indicated on the X axis. An empty vector group (HAd-ΔE1E3) was included as a negative control. Four weeks post-boost, sera were obtained for detection of neutralizing (solid bars) and hemagglutinating (empty bars) antibodies by virus microneutralization assay and HI assay using horse red blood cells, respectively.

Figure 3. HAd-H5HA vaccine induces protection against lethal challenge in a dose-dependent manner.

BALB/c mice were immunized i.m. with five consecutive log dilutions (▲109 ; ● 108 ; △107 ; X 106 ; and □105 PFU) of HAd-H5HA vaccine twice 4 weeks apart. An empty vector group (○) was included as a negative control. Four weeks post-boost, the mice were challenged with a 10 LD50 of A/Hong Kong/483/97 and monitored for clinical signs and weight loss for 14 days. The figure shows (a) percent survival after lethal challenge and (b) morbidity as determined by weight loss.

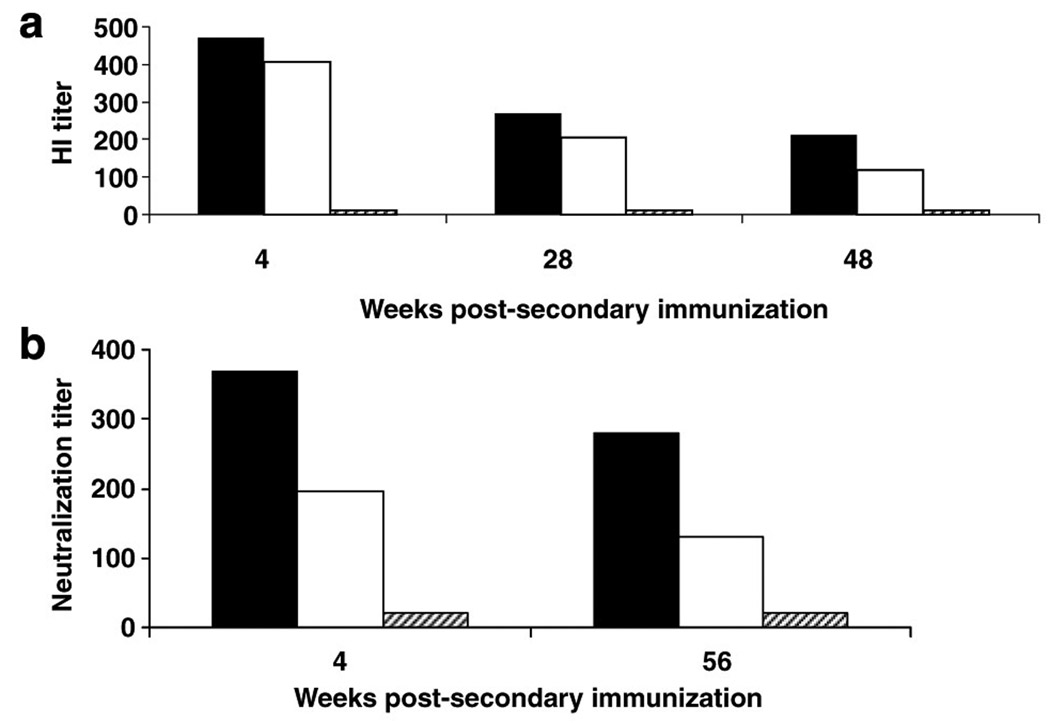

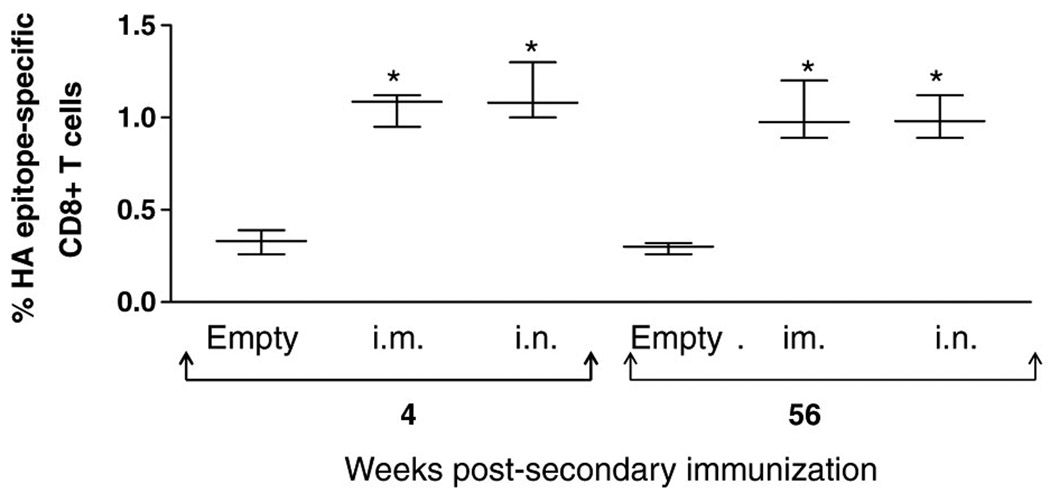

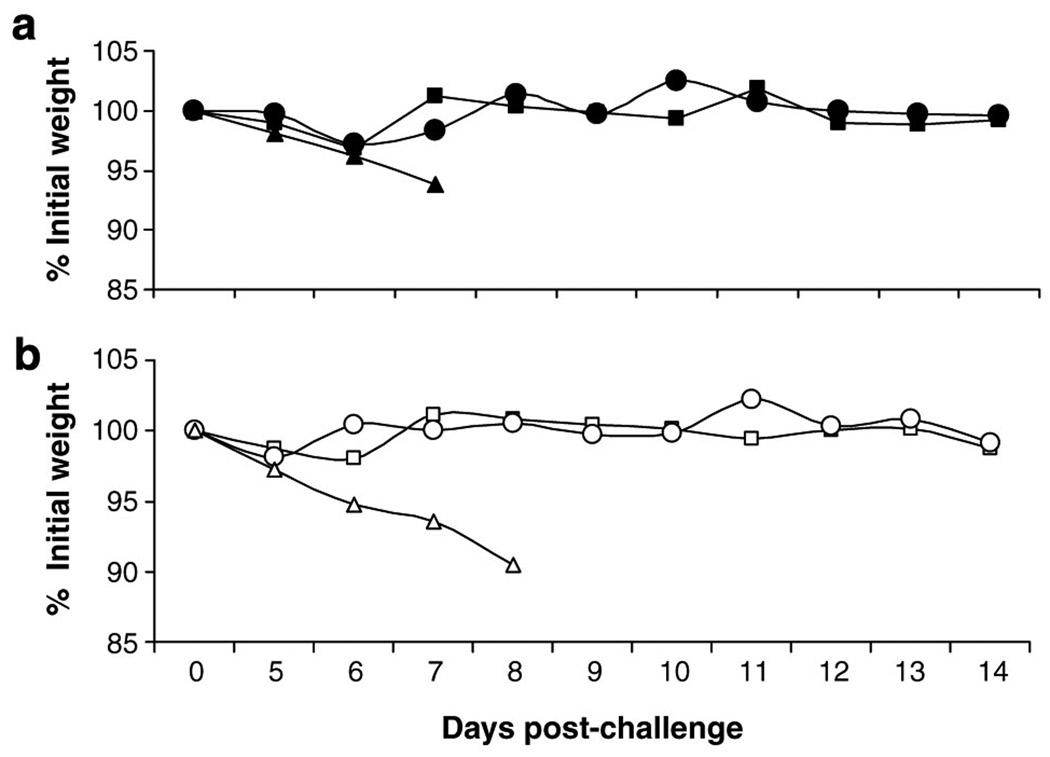

To determine if the vaccine induces durable protective immunity, mice were immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) or intranasally (i.n.) twice at 4 weeks apart with 108 PFU of HAd-H5HA vaccine or i.m. with an empty vector and bled at intervals of 4, 28, and 48 weeks post-boost to assess humoral immune responses. HI antibody titers at 4, 28, and 48 weeks as determined by a horse HI assay for i.m. immunizations were 470.3, 269.1, and 211.1, respectively, and for i.n. immunizations were 407.8, 203.9, and 117.13, respectively, whereas the HI antibodies in the empty vector group remained at background levels (Figure 4a). Comparison of prechallenge bleeds from mice receiving a booster immunization 56 weeks prior with mice receiving a booster immunization 4 weeks prior indicated that neutralizing antibody titers remain at protective levels, as shown in Figure 4b. Mice bled at 4 weeks post-boost with HAd-H5HA vaccine generated neutralizing antibody titers of 367.6 and 197 for i.m. and i.n. immunizations, respectively, whereas mice bled at 56 weeks post-immunization with the vaccine generated neutralizing titers of 278.6 and 130 for i.m. and i.n. immunizations, respectively. Analysis of HA518 epitope specific CD8 + T cells indicates that the frequency of CD8+ T-cell responses at 56 weeks post-boost was similar to the levels induced at 4 weeks post-boost (Figure 5). The frequencies of HA518 epitope-specific CD8 + T cells at 4 weeks post-boost were 1.07 and 1.08% for groups immunized by the i.m. or i.n. route, respectively, and at 56 weeks post-immunization they were 1.04 and 0.95%, respectively. Both groups had significant levels (P<0.001) of HA518 epitope specific CD8 + T cells as compared to the empty vector control groups. Nucleoprotein 147 (NP147) epitope-specific pentamer staining levels remained at background levels, indicating that the animals were not exposed to influenza viruses during the course of the study (data not shown). Following challenge with a lethal dose of HK/483 virus, all mice immunized with HAd-H5HA vaccine were protected and exhibited little or no morbidity, as indicated by weight loss (Figure 6). These data clearly indicate that HAd-H5HA vaccine generates long-lasting humoral and cellular immune responses and confers complete protection against lethal challenge even at 12 months post-immunization with no difference observed by route of immunization.

Figure 4. HAd-H5HA vaccine induces durable serological responses.

(a) BALB/c mice were immunized i.m. (solid bars) or i.n. (empty bars) with 108 PFU of HAd-H5HA or i.m. with empty vector (hatched bars) twice 4 weeks apart. Sera were obtained 4, 28, and 48 weeks post-boost for detection of antibodies by HI assay using horse red blood cells. (b) After 48 weeks, three additional groups of naive mice were immunized on the same schedule as those immunized before. Sera were obtained 4 weeks post-boost from all six groups of mice (4 weeks and 56 weeks) to determine neutralizing antibody titers by virus microneutralization assay.

Figure 5. HAd-H5HA vaccine induces long-term persistence of epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses.

BALB/c mice were immunized i.m. or i.n. with 108 PFU of HAd-H5HA or i.m. with empty vector twice 4 weeks apart and aged for 55 weeks. Three additional groups of mice were immunized on the same schedule as those immunized 48 weeks before. Spleens were harvested from four mice in each group at 4 and 55 weeks post-boost and passed through screens to obtain a single-cell suspension for each mouse. Splenocytes (1 × 106 ) were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline with 2% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% sodium azide (staining buffer) and blocked for 5 min on ice with Fc block, followed by PE (phycoerythrin)-labeled HA518 or NP147 epitope-specific pentamer and anti-CD8 antibody conjugated with APC (allophycocyanin) and analyzed by flow cytometry, with a tight gate around the CD8 + T-cell population. Data are expressed as box and whisker plots (interquartile ranges). *P<0.001.

Figure 6. HAd-H5HA vaccine confers long-term protective immunity.

(a) BALB/c mice were immunized i.m. (■) or i.n. (●) with 108 PFU of HAd-H5HA or i.m. with empty vector (▲) twice 4 weeks apart and aged for an additional 56 weeks. (b) Forty-eight weeks after the first three groups were immunized, three additional groups of mice were immunized on the same schedule as those immunized before. All groups of mice were challenged with 50 LD50 of A/Hong Kong/483/97 and monitored for clinical signs and weight loss for 14 days.

DISCUSSION

Since 2004, highly pathogenic avian influenza has been reported in birds in more than 60 countries, with 12 of those reporting human infections.3,4 More than 60% of the reported human cases have resulted in death. Current vaccines against seasonal influenza do not protect against the virulent strains of highly pathogenic avian influenza; thus, effective vaccines against highly pathogenic avian influenza are an urgent public health priority.

Two distinct clades of H5N1 viruses have emerged since 2004, thus creating additional challenges for designing and creating a universal vaccine offering protection against viruses in different clades.3,5 The current avian influenza vaccine recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2007 based on a clade 1 virus (A/Vietnam/1203/2004) induced neutralizing titers of ≥40, which are indicative of protective levels, in slightly more than half of the study participants receiving two doses at 90 µg of HA, 12 times the HA content as the seasonal vaccines.44 Inclusion of adjuvant, namely alum, in antigen dose-sparing studies with split or whole virus-inactivated vaccine or MF59-adjuvanted surrogate H5N3 vaccine has only marginally enhanced immune responses. However, Leroux-Roels et al. have recently shown that an inactivated split A/ Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14 (recombinant H5N1 engineered by reverse genetics) egg-derived vaccine at a dose of 3.8 mg with a novel adjuvant system, ASO3, induced a fourfold increase in neutralization titers against clade 1 virus in 86% of the vaccines. In addition, 77% of those vaccinated demonstrated significant levels of neutralization against a clade 2 virus.20 Previously, we found that 108 PFU of HAdH5HA was the optimal dose that generated protective immune responses determined by HI titers. Mice that received 106 PFU of vaccine had neutralizing antibodies and HI antibodies below the level of detection of the assays but still were completely protected, suggesting that protection against H5N1 lethal challenge in the absence of neutralizing antibodies or at levels below detection can be facilitated by other mechanisms, namely cell-mediated immunity or non-neutralizing and non-hemagglutinating antibodies, possibly by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. As this vaccine is administered by the i.m. route, mucosal antibodies do not play a role in protection. We have also shown earlier that although non-neutralizing antibodies play a role in the clearance of antigenically similar viruses, protection against antigenically distinct strains of influenza viruses requires cell-mediated immunity, namely cytotoxic T lymphocytes as well as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity for protection.49

Clinical trials involving traditional vaccine approaches have suggested that antibody responses generated by traditional vaccines in humans tend to wane and are not detectable 16 months post-immunization, but are detectable only after a booster immunization.50 In the case of Ad-vector vaccines, epitope-specific T cells generated against hepatitis C persisted in non-human primates for at least 12 months postimmunization,51 and HAd-delivered herpes simplex virus (glycoprotein B (AdgB8))-induced specific antibodies and CD8+ T cells after i.n. vaccination were maintained for several months.52 Similarly, antibody responses against p55gag antigen of simian immunodeficiency virus delivered by HAd were detectable 12 months post-immunization, whereas T-cell-specific responses were detectable for at least 6 months post-immunization in mice.53 Schwartz et al.54 have recently shown that protective immune responses against lethal challenge when vaccinated with a vesicular stomatitis virus vector expressing H5HA are detectable for at least 6.5 months post-boost in mice. Our data also show that humoral and cell-mediated immune responses induced by HAd-H5HA vaccine are detectable for at least 12 months post-immunization in mice. Pre-existing humoral immune responses to influenza will aid in preventing or limiting infection, whereas the pre-existing cell-mediated responses will aid in recovery or shortening the duration of illness.49,55 As both humoral and cellular immune responses induced by Ad-vector-based vaccine are long-lasting and cross-protective, the HAd-H5HA vaccine has the potential to confer protection against the drifted H5N1 variants.

The mechanisms of HAd-vector immunity due to pre-exposure to adenovirus have been addressed;56 however, as shown in two recent clinical trials, no correlation between the immune response to the antigen and pre-existing vector-specific antibodies exists in humans.40,42 Although the Ad-vector-based human immunodeficiency virus vaccine generated a slight decrease in the cell-based immune responses in subjects with pre-existing HAd5 antibodies when compared to HAd5 sero-negative groups, the decrease was minimal at higher antigen doses.

Pre-pandemic vaccines, either egg-derived or recombinant protein expressed in baculovirus, have shown to be poor in eliciting a robust immune response against antigenically similar H5N1 viruses, unless they are adjuvanted.20,44–46 Hence, it is prudent to consider alternate strategies to develop pandemic vaccines given the current manufacturing capacity constraints and dependence on embryonated eggs. Therefore, the HAd-vectored vaccine strategy is a viable option for stockpiling and could potentially be used as a pre-pandemic or pandemic vaccine.

METHODS

Immunizations and challenges

Dose–response studies

Six groups of 8-to 10-week-old BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol; Sigma, St Louis, MO) at 0.15 ml/10 g body weight and immunized i.m. in each thigh with 50 µl of decreasing log concentrations of HAd-H5HA vaccine (HAd vector expressing the HA gene from A/Hong Kong/156/1997 (HK/156)) starting at 109 PFU or empty HAd vector (HAd-ΔE1E3). Four weeks later, mice were boosted with the same concentrations of HAd-H5HA or empty vector. Sera were obtained 4 weeks post-boost by retro-orbital bleeds to determine HA-specific antibody responses by virus microneutralization assay57 and HI assay using horse red blood cells for detection of H5-specific HA antibodies.58 Mice were challenged with 10 × 50% lethal dose (LD50) of an antigenically similar influenza virus, HK/483, and monitored for 14 days for clinical signs and weight loss, an indicator of morbidity. CDC’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved all procedures involving animals. Experiments involving HK/156 and HK/483 were conducted under biosafety level 3 containment, with enhancements as required by the US Department of Agriculture and the Select Agent Program.

Longevity studies

Three groups of 8-to 10-week-old BALB/c mice (10 mice per group) were immunized i.m. under anesthesia with 50 µl of 108 PFU of HAd-H5HA or empty vector in each thigh or 50 µl of 108 PFU of HAd-H5HA i.n. under light anesthesia (CO2 gas) with 25 µl in each nostril. Four weeks later, the mice were boosted with the same vaccine and route of administration. Sera were obtained by retro-orbital bleeds at 4, 28, and 48 weeks post-boost to determine antibody-specific responses as described above. Following bleeds and eight weeks before challenge, three separate groups of mice were immunized twice i.n. or i.m. with 108 PFU of HAd-H5HA or i.m. with 108 PFU of empty vector for comparison to the mice immunized 48 weeks before. Sera were obtained by retroorbital bleeds before challenge for serological analysis as described above. Six mice per group were challenged with 50 LD50 of HK/483 and monitored for 14 days for clinical signs and weight loss. Spleens were harvested from the remaining four mice to determine cell-mediated immune responses.

Cell-mediated immune responses

A single-cell suspension of splenocytes obtained from four individual mice was subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis for epitopic-specific responses by Kd-specific (Class I MHC molecule) pentamer staining. In brief, splenocytes were prepared by gentle passage of the tissue through sterile mesh screens to create single-cell suspensions. For pentamer staining, 1 × 106 cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline with 2% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% sodium azide (staining buffer) and blocked for 5 min on ice with Fc block (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). This was followed by the addition of either PE (phycoerythrin)-labeled HA518 (HA518–526 (IYSTVASSL)) or NP147 (NP147–155 (TYQRTRALV)) epitope-specific pentamer (ProImmune, Springfield, VA) and anti-CD8 antibody-conjugated with APC (allophycocyanin) for 30 min at room temperature. CD8+T-cell events (100,000) were collected on a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur flow cytometer and the data were analyzed using CellQuest Pro software. NP147-specific pentamer was used as a negative control, as cells will stain with this pentamer only if they have been exposed to infectious virus or NP viral peptides.

Serological responses

Sera from all mice were subjected to receptor-destroying enzyme from Vibrio cholerae (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) at 37°C overnight to destroy nonspecific serum inhibitor activity. Presence of HI antibody was determined using four hemagglutination units of b-propiolactone-inactivated HK/156 virus and horse red blood cells.58 Neutralizing antibodies were determined by using a virus microneutralization assay to assess their ability to neutralize a homologous HK/156 virus.57

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work performed at Purdue University and the CDC was supported by Public Health Service Grant AI059374 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (to SKM) and National Vaccine Program Office (to SS), respectively.

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control or the funding agencies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Jong JC, Claas ECJ, Osterhaus ADME, Webster RG, Lim WL. A pandemic warning? Nature. 1997;389:554. doi: 10.1038/39218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subbarao K, et al. Characterization of an avian influenza A (H5N1) virus isolated from a child with a fatal respiratory illness. Science. 1998;279:393–396. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.OIE. Update on avian influenza in animals (type H5) 2007 / http://www.oie.int/downld/AVIAN%20INFLUENZA/A_AI-Asia.htmS. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. [Accessed 11 July 2007];Cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A/(H5N1) reported to WHO. 2007 / http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/country/cases_table_2007_07_11/en/index.htmlS. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H, et al. Establishment of multiple sublineages of H5N1 influenza virus in Asia: implications for pandemic control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2845–2850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511120103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. [Accessed 12 October 2007];Avian influenze (“bird flu”)—Fact sheet. 2007 / http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/avian_influenza/en/#roleS. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kandun IN, et al. Three Indonesian clusters of H5N1 virus infection in 2005. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:2186–2194. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ungchusak K, et al. Probable person-to-person transmission of avian influenza A (H5N1) N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The World Health Organization Global Influenza Program Surveillance Network. Evolution of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in Asia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:1515–1521. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.050644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li KS, et al. Genesis of a highly pathogenic and potentially pandemic H5N1 influenza virus in eastern Asia. Nature. 2004;430:209–213. doi: 10.1038/nature02746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horimoto T, Kawaoka Y. Strategies for developing vaccines against H5N1 influenza A viruses. Trends Mol. Med. 2006;12:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treanor JJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant hemagglutinin vaccine for H5 influenza in humans. Vaccine. 2001;19:1732–1737. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fodor E, Devenish L, Engelhardt OG, Palese P, Brownlee GG, Garcia-Sastre A. Rescue of influenza A virus from recombinant DNA. J. Virol. 1999;73:9679–9682. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9679-9682.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann E, Krauss S, Perez D, Webby R, Webster RG. Eight-plasmid system for rapid generation of influenza virus vaccines. Vaccine. 2002;20:3165–3170. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horimoto T, Kawaoka Y. Reverse genetics provides direct evidence for a correlation of hemagglutinin cleavability and virulence of an avian influenza A virus. J. Virol. 1994;68:3120–3128. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3120-3128.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luytjes W, Krystal M, Enami M, Parvin JD, Palese P. Amplification, expression, and packaging of foreign gene by influenza virus. Cell. 1989;59:1107–1113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90766-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed 12 October 2007];First “bird flu” vaccine for humans approved. 2007 / http://www.fda.gov/consumer/updates/ birdflu043007.htmlS. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maassab HF, DeBorde DC. Development and characterization of cold-adapted viruses for use as live virus vaccines. Vaccine. 1985;3:355–369. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(85)90124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. [Accessed 10 July 2007];Global pandemic influenza action plan to increase vaccine supply. 2006 / http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/CDS_EPR_GIP_2006_1.pdfS. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leroux-Roels I, et al. Antigen sparing and cross-reactive immunity with an adjuvanted rH5N1 prototype pandemic influenza vaccine: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:580–589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambhara S, Poland GA. Avian influenza vaccines: what’s all the flap? Lancet. 2006;367:1636–1638. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68657-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cinatl JJ, Michaelis M, Doerr HW. The threat of avian influenza A (H5N1). Part IV: development of vaccines. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007;196:213–225. doi: 10.1007/s00430-007-0052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillim-Ross L, Subbarao K. Emerging respiratory viruses: challenges and vaccine strategies. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006;19:614–636. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00005-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poland GA, Jacobson RM, Targonski PV. Avian and pandemic influenza: an overview. Vaccine. 2007;25:3057–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmons CP, et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of human monoclonal antibodies against H5N1 influenza. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subbarao K, Luke C. H5N1 viruses and vaccines. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e40. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoelscher MA, et al. Development of adenoviral-vector-based pandemic influenza vaccine against antigenically distinct human H5N1 strains in mice. Lancet. 2006;367:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68076-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao W, et al. Protection of mice and poultry from lethal H5N1 avian influenza virus through adenovirus-based immunization. J. Virol. 2006;80:1959–1964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1959-1964.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonnet MC, et al. Recombinant viruses as a tool for therapeutic vaccination against human cancers. Immunol. Lett. 2000;74:11–25. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisenberger A, Elliott BM, Kaufman HL. Viral vaccines for cancer immunotherapy. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2006;20:661–687. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fooks AR, et al. High-level expression of the measles virus nucleocapsid protein by using a replication-deficient adenovirus vector: induction of an MHC-1-restricted CTL response and protection in a murine model. Virology. 1995;210:456–465. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao W, et al. Effects of a SARS-associated coronavirus vaccine in monkeys. Lancet. 2003;362:1895–1896. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14962-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomez-Roman VR. HIV/AIDS prevention programs in developing countries are deficient without an appropriate scientific research infrastructure. AIDS. 2003;17:1114–1116. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200305020-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashimoto M, Boyer JL, Hackett NR, Wilson JM, Crystal RG. Induction of protective immunity to anthrax lethal toxin with a nonhuman primate adenovirus-based vaccine in the presence of preexisting anti-human adenovirus immunity. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:6885–6891. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6885-6891.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lubeck MD, et al. Immunogenicity and efficacy testing in chimpanzees of an oral hepatitis B vaccine based on live recombinant adenovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:6763–6767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morse MA. Virus-based therapies for colon cancer. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2005;5:1627–1633. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.12.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponnazhagan S, et al. Augmentation of antitumor activity of a recombinant adeno-associated virus carcinoembryonic antigen vaccine with plasmid adjuvant. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004;15:856–864. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prevec L, Christie BS, Laurie KE, Bailey MM, Graham FL, Rosenthal KL. Immune response to HIV-1 gag antigens induced by recombinant adenovirus vectors in mice and rhesus macaque monkeys. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1991;4:568–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan NJ, et al. Accelerated vaccination for Ebola virus haemorrhagic fever in non-human primates. Nature. 2003;424:681–684. doi: 10.1038/nature01876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Catanzaro AT, et al. Phase 1 safety and immunogenicity evaluation of a multiclade HIV-1 candidate vaccine delivered by a replication-defective recombinant adenovirus vector. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194:1638–1649. doi: 10.1086/509258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin X, et al. A phase I clinical trial of an adenovirus-mediated endostatin gene (E10A) in patients with solid tumors. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007;6:648–653. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.5.4004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Kampen KR. Recombinant vaccine technology in veterinary medicine. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2001;31:535–538. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(01)50607-5. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu J, Huang X, Yang Y. Innate immune response to adenoviral vectors is mediated by both Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent pathways. J. Virol. 2007;81:3170–3180. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02192-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Treanor JJ, Campbell JD, Zangwill KM, Rowe T, Wolff M. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated subvirion influenza A (H5N1) vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:1343–1351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bresson JL, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated split-virion influenza A/Vietnam/1194/2004 (H5N1) vaccine: phase I randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1657–1664. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68656-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated adjuvanted whole-virion influenza A (H5N1) vaccine: a phase I randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:991–997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicholson KG, et al. Safety and antigenicity of non-adjuvanted and MF59-adjuvanted influenza A/Duck/Singapore/97 (H5N3) vaccine: a randomised trial of two potential vaccines against H5N1 influenza. Lancet. 2001;357:1937–1943. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Condon C. A vaccine in 50 days? Lancet. 2005;366:1686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambhara S, et al. Heterosubtypic immunity against human influenza A viruses, including recently emerged avian H5 and H9 viruses, induced by FLU-ISCOM vaccine in mice requires both cytotoxic T-lymphocyte and macrophage function. Cell. Immunol. 2001;211:143–153. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stephenson I, et al. Cross-reactivity to highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 viruses after vaccination with nonadjuvanted and MF59-adjuvanted influenza A/Duck/Singapore/97 (H5N3) vaccine: a potential priming strategy. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;191:1210–1215. doi: 10.1086/428948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Capone S, et al. Modulation of the immune response induced by gene electrotransfer of a hepatitis C virus DNA vaccine in nonhuman primates. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7462–7471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenthal KL, Gallichan WS. Challenges for vaccination against sexually-transmitted diseases: induction and long-term maintenance of mucosal immune responses in the female genital tract. Semin. Immunol. 1997;9:303–314. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flanagan B, Pringle CR, Leppard KN. A recombinant human adenovirus expressing the simian immunodeficiency virus Gag antigen can induce long-lived immune responses in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 1997;78(Part 5):991–997. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-5-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwartz JA, et al. Vesicular stomatitis virus vectors expressing avian influenza H5 HA induce cross-neutralizing antibodies and long-term protection. Virology. 2007;366:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sambhara S, et al. Heterotypic protection against influenza by immunostimulating complexes is associated with the induction of cross-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 1998;177:1266–1274. doi: 10.1086/515285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goncalves MA, de Vries AA. Adenovirus: from foe to friend. Rev. Med. Virol. 2006;16:167–186. doi: 10.1002/rmv.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rowe T, et al. Detection of antibody to avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in human serum by using a combination of serologic assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37:937–943. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.937-943.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stephenson I, Wood JM, Nicholson KG, Charlett A, Zambon MC. Detection of anti-H5 responses in human sera by HI using horse erythrocytes following MF59-adjuvanted influenza A/Duck/ Singapore/97 vaccine. Virus Res. 2004;103:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]