Abstract

Cancer patients receiving doxorubicin chemotherapy experience both muscle weakness and fatigue. One postulated mediator of the muscle dysfunction is an increase in tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF), a proinflammatory cytokine that mediates limb muscle contractile dysfunction through the TNF receptor subtype 1 (TNFR1). Our main hypothesis was that systemic doxorubicin administration would cause muscle weakness and fatigue. Systemic doxorubicin administration (20 mg/kg) depressed maximal force of the extensor digitorum longus (EDL; P < 0.01), accelerated EDL fatigue (P < 0.01), and elevated serum TNF levels (P < 0.05) 72 h postinjection. Genetic TNFR1 deficiency prevented the fall in specific force caused by systemic doxorubicin, without protecting against fatigue (P < 0.01). These results demonstrate that clinical doxorubicin concentrations disrupt limb muscle function in a TNFR1-dependent manner.

Keywords: chemotherapy, cachexia, weakness, fatigue, cancer

doxorubicin (adriamycin) is an anthracycline antibiotic commonly prescribed for malignant cancers. Cardiotoxicity is a fatal side effect of doxorubicin-based chemotherapy that is minimized by limiting the dosage. Despite this precaution, patients undergoing doxorubicin chemotherapy experience both limb muscle weakness and fatigue (42). These debilitating symptoms can delay treatment, reducing the effectiveness of chemotherapy and increasing morbidity (11, 35).

Clinical data suggest that limb muscle may be weakened by doxorubicin. In patients who receive doxorubicin, maximal handgrip strength is depressed, indicating weakness, and the rate of handgrip fatigue is increased (42). In theory, such findings could reflect a change in neural activation, peripheral muscle dysfunction, or both. Muscle function after systemic doxorubicin treatment has not been tested directly.

One possible contributor to muscle dysfunction is the capacity of doxorubicin to elevate serum tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) levels. TNF is a proinflammatory cytokine produced by many cell types, including cardiac and skeletal myocytes (18, 36). TNF causes contractile dysfunction of limb muscle (1, 38) by activating the TNF receptor subtype 1, or TNFR1 (21). Circulating TNF levels are elevated in patients with cancer; doxorubicin chemotherapy exacerbates this response (6, 41). Animals treated with doxorubicin show a similar increase in circulating TNF levels (44, 47). Thus the rise in circulating TNF stimulated by doxorubicin could promote muscle dysfunction through TNFR1.

Experiments using isolated muscle preparations have yielded paradoxical results. In skinned muscle fibers, short-term doxorubicin exposure (<1 h) increases calcium sensitivity of myofilaments (9) and stimulates calcium release from isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum terminal cisternae (51). These responses predict that doxorubicin will increase submaximal force, contradicting clinical reports.

The objective of this research was to define doxorubicin effects on skeletal muscle function. We hypothesized that systemic doxorubicin administration would mimic the observed clinical effects, causing weakness and fatigue in skeletal muscle. We tested this hypothesis in mice using a clinical dose of doxorubicin and measuring force of limb skeletal muscle in vitro. We observed a depression in specific force of unfatigued muscle following doxorubicin administration and a decrease in the force developed during repetitive, fatiguing contractions. To investigate whether TNF/TNFR1 signaling mediates the systemic response, we conducted the same experiments using mice deficient in TNFR1. Our results show that TNFR1 deficiency abolishes the depression in specific force of unfatigued muscle.

In contrast to the systemic model, we hypothesized that direct, short-term exposure to doxorubicin would increase tetanic force in isolated muscle preparations. We isolated limb muscle fibers, and measured tetanic [Ca2+]i and force following direct exposure to a concentration of doxorubicin that occurs in patients. We found direct doxorubicin exposure in vitro increases intracellular calcium transients, but does not change tetanic force.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview of experimental design.

In brief, systemic studies were conducted in mice given an intraperitoneal (ip) injection of doxorubicin (20 mg/kg), then functional measurements were made on hindlimb skeletal muscle 72 h postinjection. Isolated limb muscle fibers were used to assess the effects of direct doxorubicin (2 μM) exposure for 1 h; tetanic force and cytosolic calcium concentrations, using the fluorescence indicator indo-1, were measured. Specific details of the experiments are outlined below.

Animal care.

Studies of systemic doxorubicin administration were conducted at the University of Kentucky using 6- to 8-wk-old male TNFR1 receptor-deficient mice (TNFR1−/−; B6.129-Tnfrsf1atm1Mak; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and the background strain C57BL/6 as wild types. Animals were maintained in the Division of Laboratory Animal Resources facility on a 12:12-h dark/light cycle and provided food and water ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Muscles were isolated from adult male NMRI mice to study the effect of direct doxorubicin exposure on force and free cytosolic calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]i) at the Karolinska Institutet. Animals were maintained in the animal facility at the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology on a 12:12-h dark/light cycle and provided food and water ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the Stockholm North local ethical committee.

Doxorubicin treatment.

Mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of doxorubicin (20 mg/kg; Bedford Laboratories, Bedford, OH). This dose is equivalent to doxorubicin chemotherapy given to patients with small cell lung cancer (7). The amount of doxorubicin was based on the conversion factor established by Freireich (16), which is derived from the relationship between weight and surface area of the animal. Control animals received the same volume of vehicle (phosphate buffer solution). The extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle was excised for functional studies 72 h after injection. Measurements of TNF in serum and muscle were made at 24-h time points following doxorubicin administration (24–72 h). To examine the direct effects of doxorubicin exposure, muscles were incubated in vitro for 1 h in Krebs-Ringer solution containing 2 μM doxorubicin, a dose that corresponds to serum levels in patients undergoing doxorubicin chemotherapy (37).

EDL contractile function and fatigue.

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and killed by cervical dislocation. EDL muscles were excised and placed in Krebs-Ringer solution (in mM: 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2) equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2 (pH∼7.4). The muscles were attached to a force transducer (BG Series 100g, Kulite, Leonia, NJ) using 4-0 silk suture. The force transducer was mounted on a micrometer used to adjust muscle length. The muscles were placed in a temperature-controlled organ bath between platinum wire stimulating electrodes and stimulated to contract isometrically using electrical field stimulation (Grass S48, Quincy, MA). The output of the force transducer was recorded using an oscilloscope (546601B; Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA) and a chart recorder (BD-11E; Kipp and Zonen, Delft, The Netherlands). In each experiment, the muscle was adjusted to the length where twitch force was maximal (optimal length, Lo). Lo was measured afterward using an electronic caliper (CD-6” CS, Mitutoyo America, Aurora, IL). Doxorubicin (2 μM) was added following determination of Lo for in vitro experiments. The bath temperature was then increased to 37°C, followed by an equilibration period of 30 min. One minute prior to stimulation, 25 μM (+)-tubocurarine chloride hydrate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to the organ bath. The force-frequency relationship was determined using contractions evoked at 2-min intervals using stimulus frequencies of 1 (twitch stimulus), 15, 30, 50, 80, 120, 150, 250, and 300 Hz. Pulse and train durations were 0.3 and 250 ms. Time-to-peak twitch force (TPT) and twitch half-relaxation time (1/2 RT) were also measured. Maximal tetanic contractions (Po, 300 Hz) were stimulated between submaximal frequency contractions to monitor contractile stability. One minute after the force-frequency protocol, each muscle underwent a fatigue protocol consisting of tetanic contractions every 2 s for 300 s (stimulation parameters 80 Hz, train duration 300 ms, pulse duration 0.3 ms). Following each experiment, the muscle was removed, blotted dry, and weighed. Cross-sectional area was determined as described by Close (8). Specific forces were expressed as Newtons per square centimeter.

EDL wet weight-to-dry weight ratio.

EDL muscles were excised 72 h following doxorubicin administration, blotted, weighed, and placed in a drying oven at 60°C until a constant weight was obtained (usually 48–72 h). Wet-to-dry weight ratio was computed to test for muscle edema.

Histology.

Cross sections of EDL muscles were cut on a cryostat (6 μm) and stored at −80°C. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (34). After staining slides were dehydrated in an ethanol series (85, 95, 100%), cleared with xylene, and mounted in Permount. Slides were viewed with a Nikon E600 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY). Images were captured with a Spot RT digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) and a PowerMac G4 computer (Apple, Cupertino, CA) equipped with Spot RT software, version 4.0 (Diagnostic Instruments). All fibers within the fields were counted (100–190 fibers/muscle) and analyzed for cross-sectional area using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

ELISA.

TNF was measured in serum using R&D Systems mouse-TNF-α DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's recommendations with the following modifications: 1) serum samples are incubated with capture antibody at room temperature, 2) biotinylated detection antibody was incubated for 2 h at 37°C, 3) streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was incubated for 20 min at 37°C. The HRP signal was amplified using the ELAST ELISA Amplification System according to the manufacturers recommendations (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). A microplate reader (Spectramax M2, Sunnyvale, CA) was used to detect optical density of the colorimetric signal. The concentration of TNF was calculated using a standard curve (recombinant mouse TNF-α).

Relative quantification real-time PCR.

Reverse transcription was performed with Murine-Muloney Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase and random hexamers (Promega, Madison, WI) plus 20 μg total RNA isolated from EDL muscle homogenates with TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). The mouse cDNA sequence for TNF (NM_013693) was obtained from GenBank. PCR primers were designed from the cDNA sequences using Primer Express 1.5 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primer sequences are as follows: forward 5′-TCATGCACCACCATCAAGGA-3′, reverse; 5′-GACATTCGAGGCTCCAGTGAA-3′. Synthesized primers were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). PCR was performed using Applied Biosystems 7500 Real Time PCR system. Targets were amplified from 50 ng of cDNA using SYBR Green Master Mix reagent (stage 1, 1 cycle, 50°C, 2 min; stage 2, 1 cycle, 95°C, 10 min; stage 3, 40 cycles, 95°C, 15 s, 60°C, 1 min; Applied Biosystems). Reactions were performed in duplicate or triplicate for each cDNA sample. The abundance of target mRNA relative to GAPDH mRNA was determined using the comparative cycle threshold method (19, 30).

Western blot analysis.

EDL muscles were homogenized in 2× lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.2, 2% SDS) then diluted 1:1 in 2× sample loading buffer (120 mM Tris pH 7.5, 200 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS and 0.002% Bromphenol Blue). Proteins were fractionated on 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Criterion pre-cast gels, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to reduced-fluorescence PVDF membrane (Immobilon-FL, Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes with transferred proteins were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at room temperature in Odyssey Blocking Buffer mixed 1:1 with PBS plus 0.2% Tween. Secondary antibodies were incubated for 45 min in Odyssey/PBS/0.2% Tween plus 0.01% SDS. TNF antibody was purchased from Chemicon (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Fluorescent secondary antibodies were used for detection (goat anti-mouse Alexa-680, Molecular Probes-Invitrogen; goat anti-rabbit IRD800, Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA). Fluorescence was imaged and results were quantified using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR). Results were normalized for total protein using Simply Blue stain (Invitrogen).

Intact flexor digitorum brevis fibers.

Mice were deeply anesthetized and killed by cervical disarticulation. Intact single fibers were mechanically dissected from the FDB muscle of the hindlimb as described previously (27). The isolated fiber was mounted between an Akers AE801 force transducer and adjustable holder in the perfusion channel of a muscle bath placed on the stage of an inverted microscope. Intact fibers were superfused with Tyrode solution (in mM: 121 NaCl, 5.0 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 0.4 NaH2PO4, 24.0 NaHCO3 0.1 EDTA, and 5.5 glucose) and bubbled with 5% CO2-95% O2, giving an extracellular pH of 7.4. Indo-1 (10 mM, Molecular Probes Europe) was pressure injected into fibers and used to measure [Ca2+]i, during tetanic contractions as previously described (3). This was accomplished using a system consisting of a xenon lamp, a monochromator, and two photomultiplier tubes (PTI, Wedel, Germany). Indo-1 was excited at 360 ± 5 nm and emissions were measured at 405 ± 5 nm and 495 ± 5 nm. The ratio of the light emitted at 405 nm to that at 495 nm (R) was converted to [Ca2+]i using the equation by Grynkiewicz (20):

| (1) |

where Kd is the dissociation constant of Indo-1, β is the ratio of the 495 nm signals at very low and saturating [Ca2+]i, Rmin is the ratio of very low [Ca2+]i, and Rmax is the ratio of saturating [Ca2+]i. The force-[Ca2+]i relationship was established by stimulating the fiber at 1-min intervals using stimulus frequencies of 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 70, 100, and 150 Hz, and train duration of 350 ms. The fiber was first stimulated in the absence of doxorubicin and a second time after exposure to 2 μM doxorubicin for 30 min at 24°C. Fluorescence and force signals were stored on a desktop computer system for subsequent data analysis (Felix 1.4, Photon Technology). Force data were fitted to the Hill equation:

| (2) |

using computer software (SigmaPlot, San Rafael, CA) where Ca50 is the intracellular calcium concentration required to produce half-maximal activation and n is the Hill coefficient.

Statistical analyses.

Physical characteristics of intact EDL, and twitch properties were analyzed using unpaired Student's t-tests. Differences in body weight, food and water consumption, and force-frequency curves were analyzed using two-way repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Tukey tests. Differences in TNF measurements were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. [Ca2+]i values obtained at different frequencies were analyzed using Student's t-test. Statistical calculations were performed using commercial software (SigmaStat, SPSS, Chicago, IL; Microsoft Excel, Redmond, WA). Statistical significance was accepted when P < 0.05. Results are reported as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Systemic effects of doxorubicin.

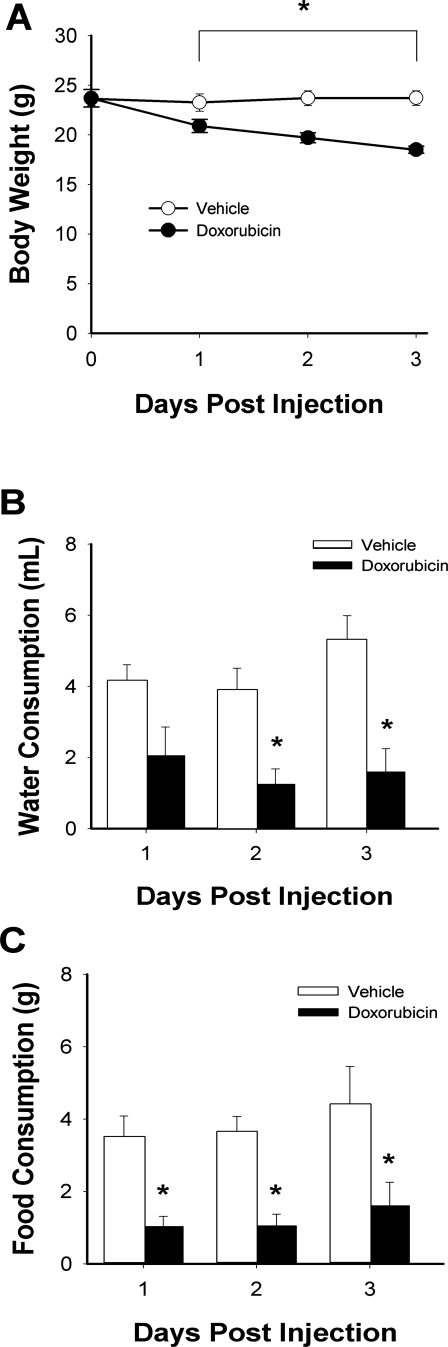

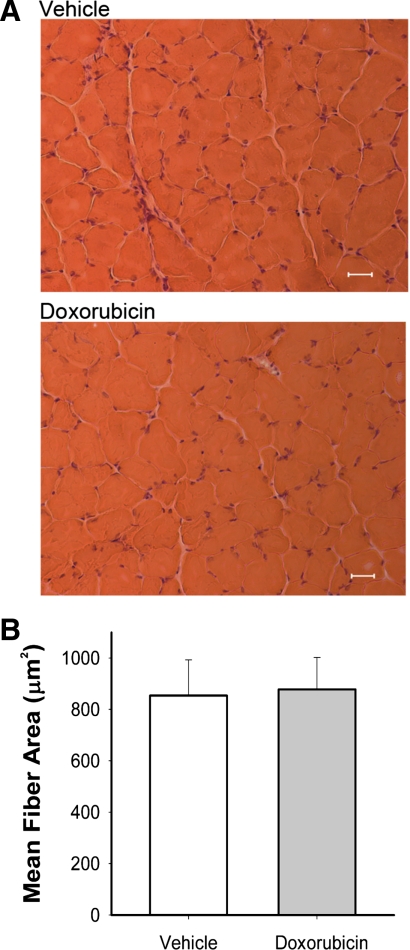

Clinical doses equivalent to treatment for patients with small cell lung cancer (7) were used for in vivo studies. Systemic doxorubicin decreased body weight over 3 days (Fig. 1A). Water and food consumption were also reduced (Fig. 1, B and C). EDL muscle weight was 20% less than vehicle-injected controls (doxorubicin 7.9 ± 0.3 vs. vehicle 9.6 ± 0.3 mg, P < 0.05) and estimated cross-sectional area was decreased (doxorubicin 0.56 ± 0.03 vs. vehicle 0.66 ± 0.02 mm2, P < 0.05) with no obvious injury or alterations of muscle fiber size (Fig. 2). Neither wet-to-dry weight ratio (doxorubicin 4.1 ± 0.1 vs. vehicle 4.2 ± 0.1) nor Lo (doxorubicin 136 ± 4 vs. vehicle 139 ± 2 mm) was different between groups.

Fig. 1.

Systemic doxorubicin decreases body weight, food intake, and water consumption. Measurements were taken for 3 days postinjection. A, body weight; B, water consumption; C, food consumption. Data are means ± SE; n = 5 (vehicle) or 6 (doxorubicin); for all panels, P < 0.05 for overall difference by repeated-measures ANOVA; *P < 0.05 by Tukey test.

Fig. 2.

Doxorubicin administration does not cause structural damage or alter fiber size in EDL muscles. A: hematoxylin and eosin stain of vehicle (top) and doxorubicin (bottom), along with mean fiber area (μm2; B) of extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles 72 h following injection. Data are means ± SE; n = 3/group. Scale bars = 12 μm.

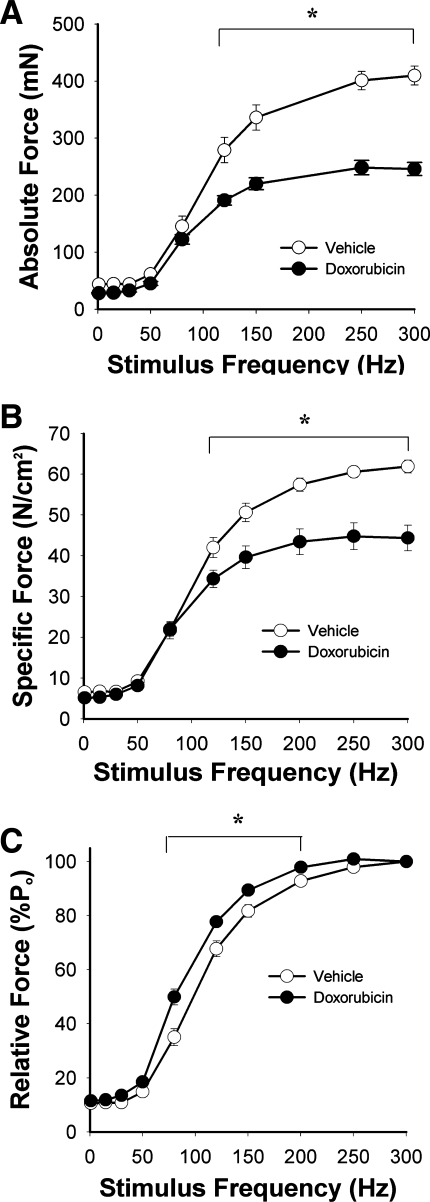

Function of EDL following systemic doxorubicin exposure.

Figure 3A depicts absolute force of EDL muscles isolated 72 h post doxorubicin injection. Maximal absolute force was depressed 40 ± 2% compared with controls. When normalized for cross-sectional area, specific force remained depressed at stimulus frequencies >120 Hz (Fig. 3B). Maximal specific force was decreased 28 ± 5% in the doxorubicin-treated group. Figure 3C depicts the relative force-frequency relationships. Doxorubicin treatment shifted the curve leftward. During twitch contractions, half-relaxation time (1/2 RT) was extended in the doxorubicin-treated group (doxorubicin 10.3 ± 1.5 vs. vehicle 7.2 ± 1.7 ms, P < 0.01). Time to peak twitch tension (TPT) was not altered (P > 0.6). Stability of the muscle, reflected by a decline in Po, was not different between groups (doxorubicin 0.72 ± 0.16 vs. vehicle 0.91 ± 0.22 %/min, P > 0.4).

Fig. 3.

Systemic doxorubicin alters contractile function of unfatigued muscle 72 h following injection. A, absolute force; B, specific force; C, relative force. Data are means ± SE; n = 5 (vehicle) or 6 (doxorubicin); for all panels, P < 0.05 for overall difference by repeated-measures ANOVA; *P < 0.01 by Tukey test.

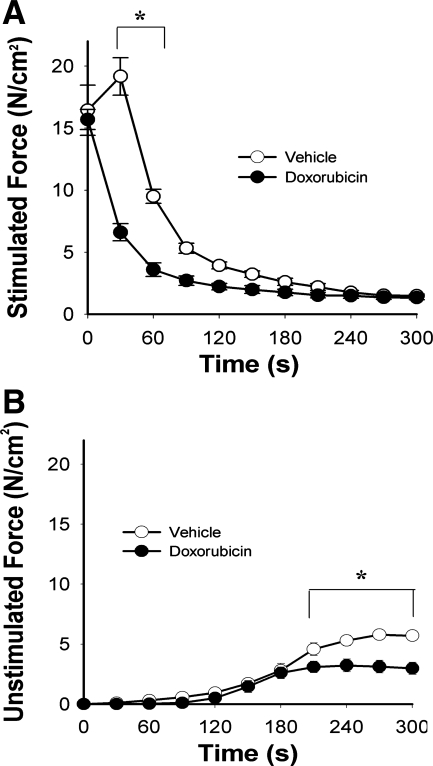

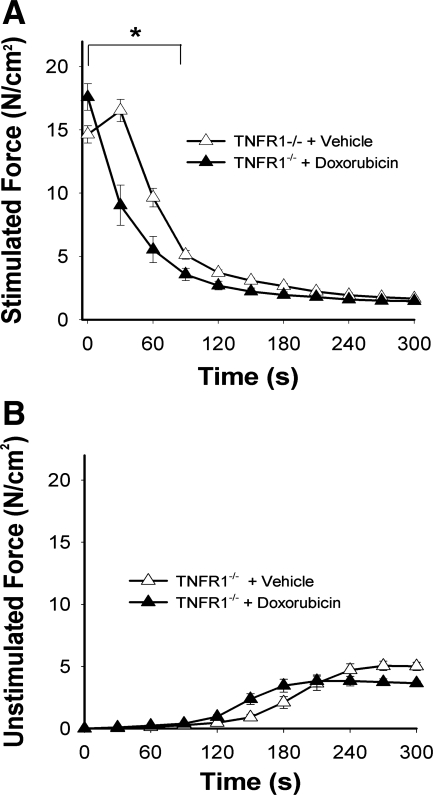

Figure 4 depicts fatigue characteristics of muscles from doxorubicin-treated mice. Specific force fell by 59 ± 5% within the first 30 s of the fatigue protocol and remained depressed relative to control through the first half of the protocol (Fig. 4A). Similarly, unstimulated force sustained by doxorubicin-treated muscle was depressed during the final 90 s of the fatigue protocol (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Systemic doxorubicin increases muscle fatigue 72 h following injection. A, stimulated force; B, unstimulated force normalized for cross-sectional area. Data are means ± SE; n = 5 (vehicle) or 4 (doxorubicin); for both panels, P < 0.05 for overall difference by repeated-measures ANOVA; *P < 0.01 by Tukey test.

TNF/TNFR1 signaling.

Circulating TNF was undetectable in control mice and elevated in doxorubicin-treated animals 24 and 72 h following doxorubicin administration (24 h: 6.2 ± 2.7 pg/ml; 72 h: 5.1 ± 1.2 pg/ml, P < 0.05). Low levels of TNF mRNA and TNF precursor protein were detected in control EDL muscles but neither was altered 24, 48, or 72 h following doxorubicin administration (P > 0.5).

The TNFR1−/− mice treated with doxorubicin showed similar declines in body weight, food intake, and water consumption over 3 days as seen in the wild-type animals (data not shown). After 72 h, body weight was less (doxorubicin 17.5 ± 0.4 vs. vehicle 22.1 ± 0.6 g, P < 0.05), as was EDL weight (doxorubicin 7.7 ± 0.2 vs. vehicle 9.1 ± 0.6 mg, P < 0.05). The 10% decrement in cross-sectional area of EDL was not statistically significant (doxorubicin: 0.54 ± 0.01 vs. vehicle 0.62 ± 0.03 mm2, P > 0.06) nor was Lo different between groups (doxorubicin 133 ± 2 vs. vehicle 137 ± 2 mm).

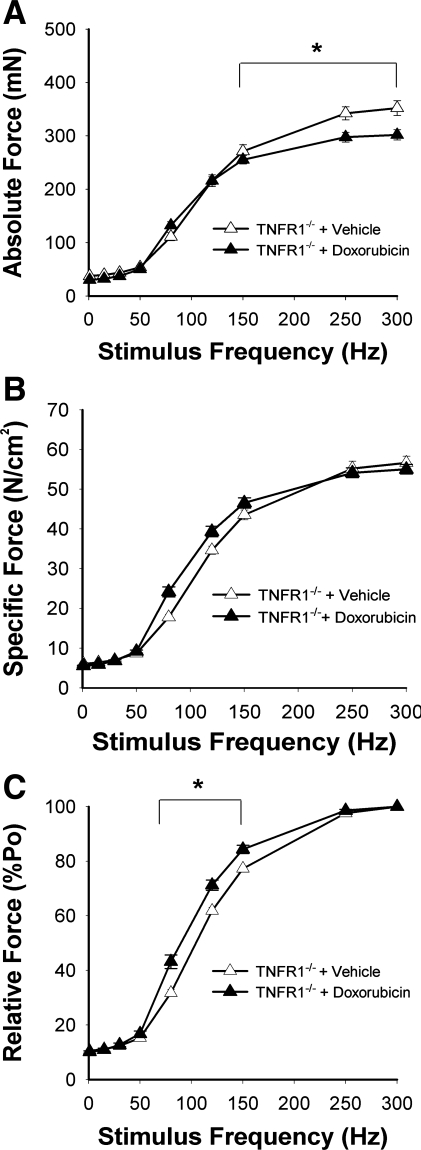

Figure 5 depicts contractile function of unfatigued EDL from TNFR1−/− mice following doxorubicin treatment. Maximal absolute force fell by only 14 ± 3% (Fig. 5A), considerably less than the 40% drop seen in doxorubicin-treated wild-type animals (P < 0.01). The depression in specific force caused by doxorubicin was abolished (Fig. 5B). The leftward shift of the relative force-frequency curve persisted (Fig. 5C), but prolongation of 1/2 RT was not statistically significant (doxorubicin 11.2 ± 0.9 vs. vehicle 9.7 ± 0.8 ms, P > 0.2) and TPT remained unaltered (P > 0.4). Doxorubicin accelerated fatigue of TNFR1−/− muscle (Fig. 6A) without affecting unstimulated force (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 5.

Doxorubicin acts via TNF receptor subtype 1 (TNFR1) to depress specific force. Functional studies performed 72 h following injection in TNFR1-deficient (TNFR1−/−) mice. A, absolute force; B, specific force; C, relative force. Data are means ± SE; n = 8/group; for A and C, P < 0.01 for overall differences by repeated-measures ANOVA; *P < 0.001 by Tukey test.

Fig. 6.

TNFR1 deficiency does not protect EDL against accelerated fatigue induced by doxorubicin. Functional studies performed 72 h following injection. A, stimulated force; B, unstimulated force normalized for cross-sectional area. Data are means ± SE; n = 8/group; for A, P < 0.05 for overall differences by repeated-measures ANOVA; *P < 0.01 by Tukey test.

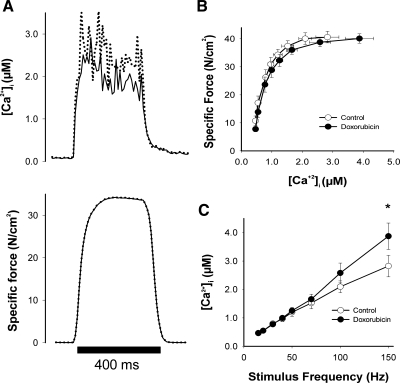

Doxorubicin exposure in vitro.

Therapeutic concentrations of doxorubicin were used during in vitro experiments, matching serum levels in patients undergoing doxorubicin chemotherapy (10, 37). We used intact single fibers from FDB muscles to measure tetanic [Ca2+]i and force following direct doxorubicin exposure (Fig. 7A). Neither tetanic [Ca2+]i nor force was altered at stimulation frequencies between 15 and 100 Hz (Fig. 7, B and C). Doxorubicin did increase tetanic [Ca2+]i by 37% at 150 Hz (Fig. 7C). This is a supramaximal stimulus frequency; accordingly, higher tetanic [Ca2+]i transients in doxorubicin-treated fibers did not increase force (Fig. 7B). Doxorubicin had no effect on myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity (Ca50: doxorubicin 0.76 ± 0.11 vs. control 0.71 ± 0.13 μM). Similar results were obtained in studies of single fibers isolated from mouse EDL (data not shown). Finally, incubation of intact EDL muscles with doxorubicin did not alter specific force (Po: doxorubicin 63.3 ± 1.5 vs. control 60.2 ± 1.1 N/cm2) or fatigue characteristics (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

In vitro doxorubicin increases intracellular calcium in intact flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) single fibers with no increase in specific force. A, original [Ca2+]i (top) and force (bottom) records from FDB muscle fibers during 150 Hz stimulation; specific force-[Ca2+]i relationship obtained from FDB fibers in the absence or presence of 2 μM doxorubicin (B) and intracellular calcium release at 24°C (C). Data are means ± SE; n = 8; for C: *P < 0.01 by Student's t-test.

DISCUSSION

Muscle weakness and fatigue are common symptoms in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Clinical reports show that patients with advanced cancer develop less limb muscle force compared with controls (42) and have impaired physical performance when undergoing doxorubicin-based chemotherapy (14). Impaired muscle function is commonly attributed to the loss of muscle mass, since cancer cachexia and muscle wasting are known clinical problems (25).

Doxorubicin caused our mice to lose weight over a 3-day period following a single injection, as confirmed by other reports (40). This same phenomenon occurs in the clinic. Tozer and colleagues (45) documented weight loss in lung cancer patients undergoing doxorubicin-based chemotherapy. One contributor to the loss in body weight is a decrease in food and water consumption by patients (15), as seen in our rodent model. This decrease in sustenance can promote catabolism and muscle wasting, both of which occur during chemotherapy. Decrements in femoral quadriceps muscle thickness are detectable by ultrasound within the first 4 wk of chemotherapy (24). A similar loss of muscle mass was evident in EDL muscles of our mice and contributed to the drop in absolute force. One potential stimulus for catabolism was circulating TNF, which can stimulate atrophy via TNFR1 (17, 39). However, TNFR1 deficiency did not abolish the decreases in food and water intake, EDL weight, or absolute force caused by doxorubicin, suggesting these responses are not dependent on TNF/TNFR1 signaling.

The loss of force that occurs independent of muscle size is less studied. This dysfunction is evident when absolute force is normalized for muscle cross section, i.e., a decline in specific force. One possible cause of doxorubicin-induced dysfunction is tissue edema, which depresses specific force by increasing muscle cross section. Others have reported that systemic doxorubicin administration causes interstitial edema in murine gastrocnemius muscle (12). However, we observed no changes in wet-to-dry weight ratio or fiber cross section in the EDL muscle, arguing against significant edema in our model. An alternative mechanism is loss of contractile regulation secondary to TNFR1 activation. In the absence of doxorubicin, TNF/TNFR1 signaling has been shown to depress specific force (21), a response that closely resembles doxorubicin-stimulated dysfunction in the current study.

Doxorubicin increases circulating TNF in patients undergoing chemotherapy (6) and rodent models of chemotherapy (29, 43) and also stimulates TNF expression by cardiac muscle (36). We found that doxorubicin increases circulating TNF without altering TNF expression by skeletal muscle. This argues against an autocrine or paracrine action of muscle-derived TNF. Instead, circulating TNF appears to function as an endocrine mediator.

TNF exerts the majority of its biological actions through the TNFR1 receptor subtype. TNF binding activates the receptor's apoptotic death domain to stimulate inflammatory and stress responses. These include increased protein turnover during cancer cachexia (31) and depression of specific force in skeletal muscle (21). TNF also stimulates oxidant production by skeletal muscle (28, 32) via a TNFR1-dependent mechanism (21). Antioxidant pretreatment opposes TNF-stimulated dysfunction (21, 28), identifying muscle-derived oxidants as essential second messengers in this response.

Oxidants can disrupt the contractile process by affecting myofibrillar proteins (4, 26) or calcium homeostasis (46, 49). Direct exposure of intact single fibers to TNF depresses specific force without altering tetanic calcium transients or resting calcium concentrations (38). This finding suggests TNF-stimulated oxidants act downstream of the calcium signal, i.e., on the myofibrillar lattice. A myofibrillar target has been confirmed by experiments using permeabilized muscle fibers from TNF-treated animals; functional studies showed that calcium-activated force was depressed with no change in calcium sensitivity or cross-bridge cycling rate (21). Similar events may mediate the TNFR1-dependent weakness stimulated by doxorubicin. Studies of permeabilized fibers from doxorubicin-treated animals are a logical next step to define the underlying mechanism.

Loss of specific force does not appear to be a direct response to doxorubicin at clinically relevant concentrations. Our in vitro experiments showed that direct doxorubicin exposure increases [Ca2+]i during tetanic stimulation. This increase was only evident at supramaximal stimulus frequencies and therefore had no effect on tetanic force. van Norren and colleagues (48) observed a significant depression in absolute force of the EDL following in vitro exposure to doxorubicin. These results were obtained using bath concentrations 35- to 75-fold higher than therapeutic serum levels in patients (10, 37) and must be interpreted with caution.

Fatigue is a debilitating symptom of cancer chemotherapy (35, 42). In our murine model, doxorubicin promoted an early onset of fatigue in electrically stimulated muscle that was not prevented by TNFR1 deficiency. Specific force fell by ∼60% within the first 30 s in doxorubicin-treated mice. One possible mechanism behind this initial drop in force is inhibition of skeletal muscle myosin light chain kinase (skMLCK). skMLCK phosphorylates myosin regulatory light chain, increasing the rate at which cross bridges enter a force-producing state and contributing to post-tetanic potentiation (50). Accordingly, genetic deficiency of skMLCK abolishes post-tetanic potentiation following repeated contractions (50). In cardiac muscle, doxorubicin treatment decreases activity of the smooth muscle isoform of MLCK (13). An analogous action in skeletal muscle, decreasing skMLCK activity, could account for early fatigue of the EDL. However, fatigue is a complex process mediated by multiple, concurrent mechanisms (2). Systematic research will be required to define the cause of premature fatigue induced by doxorubicin.

The doxorubicin dose administered to mice in our experiment is based on clinical concentrations (7). It was calculated using a standard conversion factor derived from the relationship between weight and surface area of the animal (16). The current dose is designed to achieve circulating doxorubicin levels similar to those found in patients. Johansen (22) measured circulating levels of doxorubicin in mice after a 12 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection. They found levels similar to standard clinical values: ∼1.25 μg/ml in mice vs. 1 μg/ml in patients (37). Extrapolating from our 20 mg/kg dose, serum levels in our animals are expected to be comparable, i.e., ∼2 μg/ml. At clinical doses, doxorubicin causes muscle weakness (42) that is not selective for individual muscles or fiber types. In both animals and patients, doxorubicin treatment results in loss of muscle mass that is independent of fiber type. Rabbits that received unilateral intramuscular injections of doxorubicin exhibited marked fiber atrophy but no differences in fiber type composition compared with noninjected contralateral muscle (33). In 60% of patients, limb muscles exposed to doxorubicin by isolated limb perfusion showed a significant decrease in diameter of both types I and II muscle fibers compared with pretreatment measurements (5).

In summary, this study is the first to show that systemic administration of doxorubicin at clinical doses depresses specific force of skeletal muscle. Our results show that doxorubicin causes muscle weakness and fatigue, independent of atrophy and that TNFR1 deficiency protects against doxorubicin-induced weakness. Currently there is no clinical treatment to prevent weakness and fatigue caused by cancer chemotherapy, a limitation in daily life (14). The present findings identify TNF/TNFR1 signaling as a novel target for future interventions to improve the quality of life for patients and increase the effectiveness of cancer treatment.

GRANTS

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AR-055974 and research funds at the Karolinska Institutet. Ms. Gilliam was supported by a National Institutes of Health training grant (T32-HL-086341) and a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (09PRE2020088).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Colleen McMullen and Dr. Francisco Andrade for assistance with histological analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adams V, Mangner N, Gasch A, Krohne C, Gielen S, Hirner S, Thierse HJ, Witt CC, Linke A, Schuler G, Labeit S. Induction of MuRF1 is essential for TNF-alpha-induced loss of muscle function in mice. J Mol Biol 384: 48–59, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allen DG, Lamb GD, Westerblad H. Skeletal muscle fatigue: cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev 88: 287–332, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andrade FH, Reid MB, Allen DG, Westerblad H. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and dithiothreitol on contractile function of single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. J Physiol Online 509: 565–575, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andrade FH, Reid MB, Westerblad H. Contractile response of skeletal muscle to low peroxide concentrations: myofibrillar calcium sensitivity as a likely target for redox-modulation. FASEB J 15: 309–311, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bonifati DM, Ori C, Rossi CR, Caira S, Fanin M, Angelini C. Neuromuscular damage after hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion in patients with melanoma or sarcoma treated with chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 46: 517–522, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N, Fahey JL. Fatigue and proinflammatory cytokine activity in breast cancer survivors. Psychosom Med 64: 604–611, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chabner BA, Ryan DP, Paz-Ares L, Garcia-Carbonero R, Calabresi P, Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Gilman AG. Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacologic Basis of Therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Close RI. Dynamic properties of mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol Rev 52: 129–197, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Beer EL, Finkle H, Voest EE, Van Heijst BGV, Schiereck P. Doxorubicin interacts directly with skinned single skeletal muscle fibres. Eur J Pharmacol 214: 97–100, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Delgado G, Potkul RK, Treat JA, Lewandowski GS, Barter JF, Forst D, Rahman A. A phase I/II study of intraperitoneally administered doxorubicin entrapped in cardiolipin liposomes in patients with ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 160: 812–819, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB, Andrykowski MA, Winters EM, Balducci L, Malik U, Kenady D, McGrath P. Course of fatigue in women receiving chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy for early stage breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 28: 373–380, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Doroshow JH, Tallent C, Schechter JE. Ultrastructural features of Adriamycin-induced skeletal and cardiac muscle toxicity. Am J Pathol 118: 288–297, 1985. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dudnakova TV, Lakomkin VL, Tsyplenkova VG, Shekhonin BV, Shirinsky VP, Kapelko VI. Alterations in myocardial cytoskeletal and regulatory protein expression following a single Doxorubicin injection. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 41: 788–794, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elbl L, Vasova I, Tomaskova I, Jedlicka F, Kral Z, Navratil M, Smardova L, Wagnerova B, Vorlicek J. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the evaluation of functional capacity after treatment of lymphomas in adults. Leuk Lymphoma 47: 843–851, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evans WK, Nixon DW, Daly JM, Ellenberg SS, Gardner L, Wolfe E, Shepherd FA, Feld R, Gralla R, Fine S. A randomized study of oral nutritional support versus ad lib nutritional intake during chemotherapy for advanced colorectal and non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 5: 113–124, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freireich EJ, Gehan EA, Rall DP, Schmidt LH, Skipper HE. Quantitative comparison of toxicity of anticancer agents in mouse, rat, hamster, dog, monkey, and man. Cancer Chemother Rep 50: 219–244, 1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garcia-Martinez C, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. Acute treatment with tumour necrosis factor-alpha induces changes in protein metabolism in rat skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Biochem 125: 11–18, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gielen S, Adams V, Mobius-Winkler S, Linke A, Erbs S, Yu J, Kempf W, Schubert A, Schuler G, Hambrecht R. Anti-inflammatory effects of exercise training in the skeletal muscle of patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 42: 861–868, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giulietti A, Overbergh L, Valckx D, Decallonne B, Bouillon R, Mathieu C. An overview of real-time quantitative PCR: applications to quantify cytokine gene expression. Methods 25: 386–401, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hardin BJ, Campbell KS, Smith JD, Arbogast S, Smith J, Moylan JS, Reid MB. TNF-α acts via TNFR1 and muscle-derived oxidants to depress myofibrillar force in murine skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 104: 694–699, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johansen PB. Doxorubicin pharmacokinetics after intravenous and intraperitoneal administration in the nude mouse. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 5: 267–270, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kang YJ, Sun X, Chen Y, Zhou Z. Inhibition of doxorubicin chronic toxicity in catalase-overexpressing transgenic mouse hearts. Chem Res Toxicol 15: 1–6, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koskelo EK, Saarinen UM, Siimes MA. Skeletal muscle wasting and protein-energy malnutrition in children with a newly diagnosed acute leukemia. Cancer 66: 373–376, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kotler DP. Cachexia. Ann Intern Med 133: 622–634, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lamb GD, Posterino GS. Effects of oxidation and reduction on contractile function in skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. J Physiol 546: 149–163, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lännergren J, Westerblad H. The temperature dependence of isometric contractions of single, intact fibres dissected from a mouse foot muscle. J Physiol 390: 285–293, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li X, Moody MR, Engel D, Walker S, Clubb FJ, Jr, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL, Reid MB. Cardiac-specific overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha causes oxidative stress and contractile dysfunction in mouse diaphragm. Circulation 102: 1690–1696, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lien YC, Lin SM, Nithipongvanitch R, Oberley TD, Noel T, Zhao Q, Daosukho C, St Clair DK. Tumor necrosis factor receptor deficiency exacerbated Adriamycin-induced cardiomyocytes apoptosis: an insight into the Fas connection. Mol Cancer Ther 5: 261–269, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-ΔΔC(T)) method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Llovera M, Garcia-Martinez C, Lopez-Soriano J, Carbo N, Agell N, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. Role of TNF receptor 1 in protein turnover during cancer cachexia using gene knockout mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol 142: 183–189, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mariappan N, Soorappan RN, Haque M, Sriramula S, Francis J. TNF-α-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress and cardiac dysfunction: restoration by superoxide dismutase mimetic Tempol. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2726–H2737, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McLoon LK, Falkenberg JH, Dykstra D, Iaizzo PA. Doxorubicin chemomyectomy as a treatment for cervical dystonia: histological assessment after direct injection into the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Muscle Nerve 21: 1457–1464, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McMullen CA, Andrade FH. Contractile dysfunction and altered metabolic profile of the aging rat thyroarytenoid muscle. J Appl Physiol 100: 602–608, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miller M, Maguire R, Kearney N. Patterns of fatigue during a course of chemotherapy: results from a multi-centre study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 11: 126–132, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mukherjee S, Banerjee SK, Maulik M, Dinda AK, Talwar KK, Maulik SK. Protection against acute adriamycin-induced cardiotoxicity by garlic: role of endogenous antioxidants and inhibition of TNF-alpha expression. BMC Pharmacol 3: 16, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Piscitelli SC, Rodvold KA, Rushing DA, Tewksbury DA. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of doxorubicin in patients with small cell lung cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther 53: 555–561, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reid MB, Lannergren J, Westerblad H. Respiratory and limb muscle weakness induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha: involvement of muscle myofilaments. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 479–484, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reid MB, Li YP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and muscle wasting: a cellular perspective. Respir Res 2: 269–272, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rephaeli A, Waks-Yona S, Nudelman A, Tarasenko I, Tarasenko N, Phillips DR, Cutts SM, Kessler-Icekson G. Anticancer prodrugs of butyric acid and formaldehyde protect against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Br J Cancer 96: 1667–1674, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Salles G, Bienvenu J, Bastion Y, Barbier Y, Doche C, Warzocha K, Gutowski MC, Rieux C, Coiffier B. Elevated circulating levels of TNFα and its p55 soluble receptor are associated with an adverse prognosis in lymphoma patients. Br J Haematol 93: 352–359, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stone P, Hardy J, Broadley K, Tookman AJ, Kurowska A, A'Hern R. Fatigue in advanced cancer: a prospective controlled cross-sectional study. Br J Cancer 79: 1479–1486, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tangpong J, Cole MP, Sultana R, Estus S, Vore M, St CW, Ratanachaiyavong S, St Clair DK, Butterfield DA. Adriamycin-mediated nitration of manganese superoxide dismutase in the central nervous system: insight into the mechanism of chemobrain. J Neurochem 100: 191–201, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tangpong J, Cole MP, Sultana R, Joshi G, Estus S, Vore M, St CW, Ratanachaiyavong S, St Clair DK, Butterfield DA. Adriamycin-induced, TNF-alpha-mediated central nervous system toxicity. Neurobiol Dis 23: 127–139, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tozer RG, Tai P, Falconer W, Ducruet T, Karabadjian A, Bounous G, Molson JH, Droge W. Cysteine-rich protein reverses weight loss in lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Antioxid Redox Signal 10: 395–402, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tupling AR, Vigna C, Ford RJ, Tsuchiya SC, Graham DA, Denniss SG, Rush JW. Effects of buthionine sulfoximine treatment on diaphragm contractility and SR Ca2+ pump function in rats. J Appl Physiol 103: 1921–1928, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Usta Y, Ismailoglu UB, Bakkaloglu A, Orhan D, Besbas N, Sahin-Erdemli I, Ozen S. Effects of pentoxifylline in adriamycin-induced renal disease in rats. Pediatr Nephrol 19: 840–843, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van Norren K, van Helvoort A, Argiles JM, van Tuijl S, Arts K, Gorselink M, Laviano A, Kegler D, Haagsman HP, van der Beek EM. Direct effects of doxorubicin on skeletal muscle contribute to fatigue. Br J Cancer 100: 311–314, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Viner RI, Williams TD, Schoneich C. Peroxynitrite modification of protein thiols: oxidation, nitrosylation, and S-glutathiolation of functionally important cysteine residue(s) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase. Biochemistry 38: 12408–12415, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhi G, Ryder JW, Huang J, Ding P, Chen Y, Zhao Y, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Myosin light chain kinase and myosin phosphorylation effect frequency-dependent potentiation of skeletal muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 17519–17524, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zorzato F, Salviati G, Facchinetti T, Volpe P. Doxorubicin induces calcium release from terminal cisternae of skeletal muscle. A study on isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum and chemically skinned fibers. J Biol Chem 260: 7349–7355, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]