Abstract

Background

There is debate about how best to measure patient reported outcomes (PROs) in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). We pooled data from clinical trials to measure the psychometric properties of IBS endpoints, including binary responses (e.g. “adequate relief”) and 50% improvement in symptom severity.

Methods

We pooled patient-level data from 12 IBS drug trials involving 10,066 participants. We tested the properties of binary response and 50% improvement endpoints, including the impact of baseline severity on performance, and measured construct validity using clinical anchors. We calculated confidence intervals for the psychometric parameters of each endpoint, and compared estimates side-by-side between PROs.

Results

There were 9044 evaluable subjects (age=44; 85% F; 58% IBS-C; 31% IBS-D). Using the binary endpoint, the proportion responding in the mild, moderate, and severe groups was 42%, 40%, and 38%, respectively (p=0.0008). There was no effect of baseline severity on binary response (OR=0.99; CI=0.99–1.0; p=0.07). The proportions reaching 50% improvement in pain were 45%, 41%, and 41% respectively; there was a small, yet significant, impact of baseline severity (OR=1.04; CI=1.03–1.05; p<0.0001) that did not meet criteria for clinical relevance. Both endpoints revealed strong construct validity, and detected “minimally clinically important differences” (0.5 SD) in bowel symptoms. Both endpoints provided better discriminant spread in IBS-D than IBS-C subgroups.

Conclusions

Both the traditional binary and 50% improvement endpoints are equivalent in their psychometric properties. Neither is impacted by baseline severity, and both demonstrate excellent construct validity. They are optimized for the IBS-D population, but also appear valid in IBS-C.

Keywords: Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Endpoints, Outcomes, Meta-analysis, Psychometrics

BACKGROUND

There is debate about how best to measure patient reported outcomes (PROs) in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). This debate is important, because IBS remains a patient reported condition that cannot yet be reliably diagnosed or monitored with biomarkers alone; patient reports are essential. In the absence of valid and reliable biomarkers to accurately sub-stratify patients within an otherwise heterogeneous condition, clinicians and investigators are left interpreting patient reported symptoms to determine the diagnosis, gauge overall disease severity, develop rational treatment plans, and assess outcomes.

This challenge is now front and center for clinicians, investigators, and regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The charge for all stakeholders is to identify one or more PRO measures that are sufficiently reliable and valid, both for clinical trials and clinical practice. An optimal PRO measure must be easily administered, able to discriminate between important patient sub-groups and disease states in a statistically significant and clinically relevant manner, predictable in behavior when tracked with other indicators of illness severity, not conditional on baseline severity, and readily interpretable.1

Most all of the recent high quality clinical trials in IBS employed a binary PRO endpoint, such as “adequate relief,” “satisfactory relief,” or “considerable relief.”2 These endpoints have two levels, and therefore provide a dichotomous stratification of responder status (yes/no relief). Binary endpoints are useful because they are easy to administer and straightforward to interpret.2, 3 Moreover, they have been retrospectively shown to have construct validity when compared against other endpoints in IBS,4 and they have predicted effectiveness of medications and improvement in quality of life measures.20 On this basis, recent systematic reviews of the published evidence of IBS endpoints support the use of binary endpoints as standard for IBS clinical trials.2, 3

However, binary endpoints have been criticized on several grounds. First, Whitehead and colleagues observed that “satisfactory relief” of bowel symptoms – a type of binary endpoint – appeared to be confounded by baseline IBS severity.5 The authors found that patients with severe IBS who received usual care in a health maintenance organization were less likely to achieve a response over time compared to those with less severe IBS. In contrast, patients with less severe IBS were most likely to achieve “satisfactory relief” over time, but revealed no improvements in symptom severity. Although other investigators have not confirmed these findings in different IBS populations exposed to either pharmacological or behavioral therapy in clinical trials,6–8 the results from Whitehead et al. suggest that the performance of binary endpoints might partly depend on baseline severity. In theory, a reliable PRO measure should not be conditional on baseline severity. However, evaluation using the “adequate relief” endpoint in a randomized, placebo controlled trial did not reveal responses to be sensitive to patient baseline severity.2 Second, it has been argued that binary endpoints may not detect minimally clinically important differences (MCIDs) in symptoms or health related quality of life (HRQOL), and do not provide enough resolution to detect small changes in health status over time. Third, it is claimed that the binary endpoints lack sufficient capacity to track key illness domains or successfully discriminate between clinical sub-groups or disease states. Finally, these endpoints were not derived from patient focus groups – the “gold standard” approach for developing endpoints.1

The use of a multi-item symptom questionnaire is an alternative to binary endpoints.2 However, only one IBS-specific symptom severity questionnaire has been shown to be responsive to treatment effects: the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS).9, 10 Whitehead and colleagues have shown that the IBS-SSS is not conditional on baseline severity, and proposed a “50% improvement” criterion for establishing a responder, in which patients improving by at least 50% from their baseline severity score are considered to have clinically improved.5 When using the 50% improvement criterion, Whitehead et al. found that response to usual care was not dependent on baseline severity, and therefore proposed that the 50% improvement definition may be superior to binary endpoints, e.g. “adequate relief” or “satisfactory relief.”5

In light of this background, we performed a large pooled analysis of patient-level data from existing clinical trials to evaluate and compare the psychometric properties of endpoints used in IBS trials, including binary responses and 50% improvement in symptom severity. We retrospectively tested the properties of these endpoints by pooling patient-level data from 12 trials including over 10,000 patients. The specific aims were to determine whether either type of PRO endpoint is influenced by baseline IBS severity, and whether any of the responder definitions can detect MCIDs in cardinal IBS bowel symptoms, patient reported visceral sensitivity, disease-targeted HRQOL, psychological distress, and work productivity – all components of the evolving model of IBS illness severity.11, 12

METHODS

Pooling Patient Level Data from Databases of IBS Clinical Trials

Prior to conducting psychometric analyses of IBS endpoints, we first sought to pool patient-level data from available trials. This allowed the opportunity to maximize the robustness and explanatory power of its findings, and to test whether those findings can be generalized across data sets. The sections below describe the steps followed to systematically acquire, evaluate, and harmonize data from existing clinical trials.

Data Acquisition

We identified pharmaceutical companies that have previously conducted randomized, controlled clinical trials in IBS. We contacted each company, and provided documentation describing the study objectives and proposed analyses. Six companies provided evaluable patient-level trial data, including AstraZeneca (1 study), GlaxoSmithKline (2 studies), Ironwood (1 study), Novartis Pharmaceuticals (5 studies), and Solvay (3 studies). Table 1 provides an overview of the data employed for this pooled analysis. There were 10,066 subjects in the combined data set, of which 9,044 had minimum required data in order to be eligible for inclusion in our analyses (i.e. baseline and follow-up bowel symptom scores, and end-of-study or “last observation carried forward” [LOCF] binary response, as described further below).

Table 1.

Overview of Studies Included in Endpoints Meta-Analysis (M=Men; W=Women).

| Company | Number of Data Sets | Number of Studies | Study Name(s) | Study Treatment Duration | Study Population | N of Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novartis | 3 | 5 | A0301 A0351 A0358 A2306 A2417 |

12 Wks 12 Wks 12 Wks 4 Wks 4 Wks |

IBS-C M&W IBS-C M&W IBC-C W IBS-C W IBS-C/A W |

881 799 1519 2660 661 |

| Glaxo SmithKline | 28 | 2 | SB- 22341 2/067 SB- 22341 2/068 |

8 Wks 8 Wks |

IBS, M&W | |

| Astra Zeneca | 11 | 1 | AZ37371 | 12 Wks | IBS-C, D, A M&W |

402 |

| Solvay | 24 | 3 | S3006 S3009 S3011 |

12 Wks 26 Wks 12 Wks |

IBS-D | 711 805 193 |

| Ironwood | 1 | 1 | 103–202 | 12 Wks | IBS C | 85 |

| TOTAL | 12 | 10,066 |

Initial Data Management and Mapping

We developed a list of content areas represented in the included trials that would serve as the focus for data analysis. We then grouped the content areas into major and minor domains, as displayed in Table 2. We created a single harmonized extract data file that transformed the various data structures and variables into a common format across each study. We retained both baseline and study endpoint variables for the analyses. We relied on pre-calculated LOCF variables, when available, for patients unable to complete the full study duration.

Table 2.

Variables Included in Datasets, Grouped by Major and Minor Domains. The scaling and instrumentation for each minor domain varied considerably from study to study. Refer to the text for the method of harmonization across studies.

| Major Domain | Minor Domain |

|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Age |

| Sex | |

| IBS Subtype | |

| Treatment Status | |

| IBS Duration | |

| Study Length | |

| Bowel Symptoms | Bloating |

| Pain | |

| Frequency | |

| Consistency | |

| Urgency | |

| Hard Stool | |

| Incomplete Defecation | |

| Straining | |

| Quality of Life | Overall HRQOL |

| Activity Interference | |

| Dysphoria | |

| Food avoidance/Diet | |

| Health Worry | |

| Body Image | |

| Relationship | |

| Sex | |

| Social | |

| Sleep | |

| Fatigue | |

| Psychological | Anxiety |

| Depression | |

| Visceral anxiety | |

| Work Productivity | Presenteeism |

| Absenteeism | |

| Overall impairment | |

| Binary Outcomes | Global adequate relief |

| Pain relief | |

| Global Improvement | Continuous global improvement |

Standardizing of Variables

There are important challenges and potential barriers to successfully harmonizing data from several studies. These include disparate binary outcome measures (e.g., “satisfactory relief” vs. “adequate relief” vs. “considerable relief”), measures of IBS severity (e.g. “pain severity” vs. IBS-SSS), and scales for all covariates (e.g., 5-point vs. 7-point Likert scales). To allow for cross-trial analysis, we converted each of the continuous variables to a common scale. This involved the following steps:

Within each study, calculation of the mean and standard deviation of each baseline measure.

Use of these values to transform the variable to a standardized z-score (e.g., (z=x−μ)/σ).

For ease of interpretation, re-centering of the distribution to a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 10 – a variation of the traditional T-scale (e.g., T=(z*10)+100).

Application of the same steps that were used to transform the baseline score to the study endpoints and LOCF versions of the respective variables. By using the baseline values, any absolute changes from baseline to end-of-study would be retained in the scale transformation.

Calculation of “Minimum Clinically Important Difference” (MCID) Scores

For binary endpoints, responses of satisfactory relief, adequate relief, or considerable relief are presumed to reflect clinically significant outcomes. Although some outcome measures have empirically derived MCIDs (e.g., the MCID of the IBS-QOL is between 10 and14),13 most linear endpoints have no established MCID benchmarks. In the absence of empiric MCID definitions, one established technique recommended by Norman et al. is to assume that a half standard deviation (SD) improvement (effect size of 0.5) equates with meaningful change.14 This approach is based on the “remarkable universality” of a half SD as a surrogate measure for clinical importance, and correlates with a “medium” effect size using the traditional rules of Cohen.15 The half SD technique has been used by previous investigators in IBS, including the developers of the IBS-QOL instrument.13 The Norman approach allows for standardization of a MCID definition across disparate measures, and thus serves as an “exchange currency” to pool various outcome measures and covariates in the same analysis.

We also calculated MCIDs for all linear variables, and assigned end-of-study MCID status for each domain in each patient. To do this, we first calculated a “baseline to study endpoint change score” for each domain, using subjects with harmonized scale scores at both time points. We evaluated whether the size of the change score exceeded one-half standard deviation which was 5 given a standard deviation of 10 on the harmonized T-scale.14

Construction of Binary Endpoint

A version of the binary endpoint was constructed for each subject using the result reported in the original trial (e.g. “adequate relief”). Although the various included endpoints had different wording, they all shared in common a binary response scale. For purposes of meta-analysis, we assumed that patients understood a similar meaning from the various questions (e.g. “adequate relief” vs. “considerable relief” [yes, no]) to allow harmonization across binary endpoints. This assumption, although arguable, allows for construction of a large harmonized database; meta-analysis inevitably requires the assumption that combined data are sufficiently alike to allow for harmonization. If a subject was missing the end of study binary endpoint data, we substituted the LOCF version of the measure. In this manner, we were able to include patients who did not complete the full study but nonetheless contributed data in the form of an LOCF data point.

Creation of a Harmonized Pain Severity Scale

Because all the studies included a measure of abdominal pain at baseline and follow-up, and since pain is one of the cornerstones of “IBS severity,”11, 12 we adopted pain as our surrogate for IBS illness severity. All studies provided data regarding abdominal pain, thus providing an opportunity to create a harmonized “severity” scale based on pain. As with the other harmonized T-scales, we created a harmonized pain severity score, with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 10 (higher scores indicated higher severity).

Impact of Baseline Severity on Performance of Endpoints of Interest

We assessed the relationship between baseline severity and end-of-study response status using two competing “responder” definitions: (1) harmonized binary response status; and (2) 50% improvement in severity. We defined a “50% responder” as someone who reported at least a 50% reduction in IBS pain severity over time on the harmonized pain scale described above, using the baseline severity score as the reference point.

Using the harmonized pain severity scale, we divided patients at baseline into three severity levels, as defined by tertiles from the harmonized baseline severity T-scale (i.e., mild=bottom tertile, moderate=middle tertile, severe=top tertile). We then measured end-of-study binary response status stratified across the three severity groups to determine whether each endpoint was influenced by baseline IBS severity.

To answer the question whether each endpoint has utility in assessing treatment response across varying levels of baseline IBS symptom severity, we repeated the analyses within treatment sub-groups, first limiting to treatment arms only, then to placebo arms, and then to all data combined. For all analyses, we compared response status across tertiles using chi-squared, and adopted a p-value <0.05 as our definition of statistical significance.

Consideration of Clinical Relevance

Because the sample size is large, we anticipated that some differences might be statistically significant but not clinically relevant. To estimate the clinical relevance of differences across responder groups, we performed a separate set of analyses for each responder definition in which we measured mean baseline severity in responder vs. non-responder groups using T-tests. Because the MCID on the harmonized severity scale was set at 5, any difference between groups less than 5 indicated sub-MCID differences and was deemed to be of small to non-existent clinical significance. For between-group differences in subjects receiving investigational treatment, the MCID was assessed for significance using the rules of Cohen.16

Regression models

We performed a series of multivariable logistic regression models to measure the independent effect of baseline IBS severity on end-of-study response status for each of the three response definitions. These models adjusted for IBS sub-type, treatment status, age, sex, and disease duration.

Prospective Analysis of Construct Validity of Endpoints of Interest

We performed a series of prospective construct validity analyses to measure the performance of the competing responder definitions. For these analyses we measured the ability of each responder definition to track with several clinically important IBS constructs, including the cardinal bowel symptoms (abdominal pain, bloating, stool frequency, stool form, urgency, incomplete evacuation, straining), patient reported visceral sensitivity (using the visceral sensitivity index [VSI], a 15-item scale that is a reliable and valid measure of gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety17), HRQOL, and work productivity.

For each responder definition (e.g. binary endpoint or 50% improvement), we assessed construct validity by conducting a series of T-tests to compare change scores in each construct stratified by response status. We calculated the p-value for each comparison (responder vs. non-responder), adopting <0.05 as evidence for statistical significance. However, due to the large sample size, we also adopted a measure of clinical relevance, that is achievement of an MCID using the 0.5 SD definition.14 For this set of analyses, we calculated the proportion of patients achieving an MCID over time for each construct stratified by response status. Because the results might vary by IBS sub-type, we repeated the analyses in IBS-C and IBS-D sub-groups, and report the results both in combination and separately.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

There were 9044 evaluable subjects in the 12 trials. The mean age was 44.3 years and 85% were female. More than half of the sample had IBS-C (58%), and 31% IBS-D. Fifty-three percent of the cohort had received an investigational IBS treatment, whereas the rest received placebo. Using the binary response definition, 60% of the overall cohort achieved a response at the end of the study follow-up period. Table 3 displays the key descriptive statistics of patients included in the sample.

Table 3.

Subject Descriptive Statistics from Harmonized Patient-Level Dataset of IBS Clinical Trials

| Variable | Aggregate Mean | N |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (% Female) | 84.8% | 9044 |

| Age (years) | 44.3 ±12.7 | 9044 |

| Duration of IBS (years) | 11.3 ±11 | 6090 |

| IBS Sub-Groups | ||

| % IBS-Constipation | 57.9% | 9044 |

| % IBS-Diarrhea | 31.4% | |

| % IBS-Other | 10.7% | |

| Treatment Groups | ||

| % Receiving Treatment | 53.4% | 9044 |

| % Receiving Placebo | 46.6% | |

| Trichotomized Baseline Severity | ||

| % Mild (bottom tertile) | 34.5% | 8457 |

| % Moderate (middle tertile) | 33.5% | |

| % Severe (top tertile) | 31.9% | |

| End-of-Study Responder Status | ||

| % Responder | 59.8% | 9044 |

| % Non-Responder | 40.2% | |

Effect of Baseline Severity on Responder Status for the Binary Responses

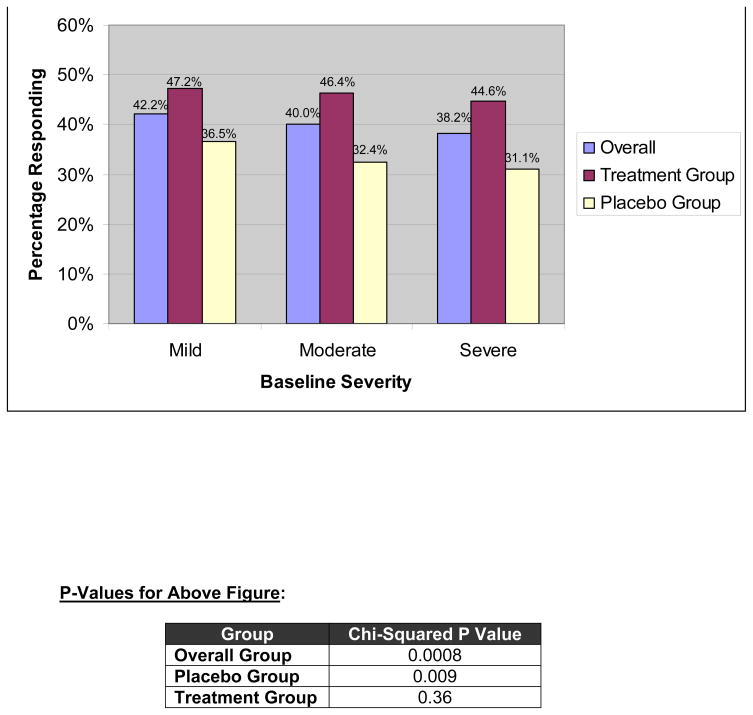

There were 8457 subjects with data included in the analyses with data comparing binary response status with baseline severity. Figure 1 portrays the percentage of patients responding, using the binary definition, stratified by baseline severity tertiles. The data are provided for three groups: all subjects combined, subjects receiving investigational treatment, and subjects receiving placebo.

Figure 1.

Relationship Between Trichotomized Baseline Severity and Responder Status, Defined using Harmonized Binary Endpoint (aka “Adequate Relief”). Data are provided for the overall, treatment, and placebo groups.

The proportion achieving a response in the mild, moderate, and severe groups was 42%, 40%, and 38%, respectively. Because of the large sample size, these differences were highly significant for both the overall group (p=0.0008) and placebo sub-group (p=0.009), but not for the investigational treatment group (p=0.36) using a chi-square test. However, multivariable analysis using data from both groups and adjusting for age, IBS sub-type, sex, disease duration and baseline pain as a continuous variable (N=5510 for model), found a non-significant relationship between baseline pain severity and response status (OR=0.995; 95% CI=0.99–1; p=0.07).

Table 4 provides the results of the T-test comparing mean baseline severity scores in patients with vs. without end-of-study (or LOCF) binary response, stratified by treatment status. The data reveal that the absolute differences in baseline severity by binary status were small for each group. For example, the absolute difference in the combined group was 0.6 points, which is below the a priori MCID of 5 points, and indicating that the differences were not clinically significant for any of the sub-groups.

Table 4.

T-Test Comparing Baseline Severity between responders vs. non-responders. The top panel provides data stratified by the harmonized binary response endpoint, and the lower panel provides data stratified by 50% improvement in symptom severity. See text for details.

| Binary Responder Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Severity Score (±SD) in Responders | Mean Severity Score (±SD) in Non-Responders | P-Value for T-Test | |

| Treatment and Placebo Groups Combined | 99.6 ±10 | 100.2 ±9.9 | 0.01 |

| Treatment Group Alone | 99.8 ±9.9 | 100.2 ±10.0 | 0.70 |

| Placebo Group Alone | 99.2 ±10.2 | 100.2 ±9.9 | 0.01 |

| 50% Improvement in Symptom Severity | |||

| Treatment and Placebo Groups Combined | 99.5 ±10.1 | 100.2 ±9.7 | 0.03 |

| Treatment Group Alone | 99.4 ±10.1 | 97.3 ±10.0 | <0.001 |

| Placebo Group Alone | 99.8 ±9.9 | 100.1 ±9.8 | 0.24 |

Effect of Baseline Severity on Responder Status 50% Improvement Responder Status

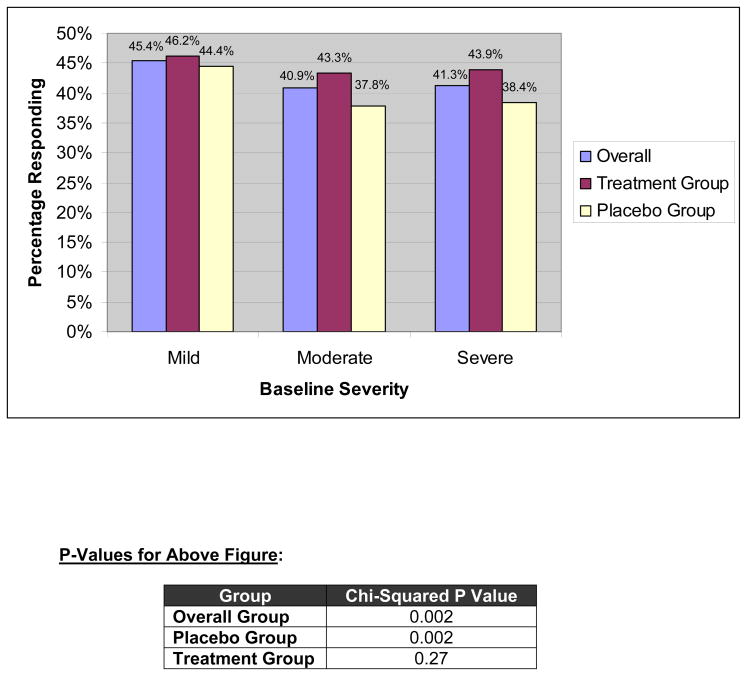

There were 7487 subjects with data comparing 50% improvement in pain severity response status with baseline severity. Figure 2 portrays the percentage of patients responding, using the 50% improvement definition, stratified by baseline severity tertiles. The proportion achieving 50% improvement in the mild, moderate, and severe groups was 45%, 41%, and 41%, respectively. The chi-squared p-value was highly significant for both the overall group and placebo groups (p=0.002 for both), but not for the treatment group (p=0.27). In multivariable logistic regression analysis with baseline pain as a continuous predictor and adjusting for potential confounders, the relationship between baseline severity and 50% improvement status was statistically significant (OR=1.04; 95% CI=1.033–1.047; p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Relationship Between Trichotomized Baseline Severity and Responder Status, Defined using 50% Improvement from Baseline Severity. Data are provided for the overall, treatment, and placebo groups.

Although baseline severity independently predicted end-of-study 50% improvement in severity, the relationship was numerically small. To test for clinical relevancy, we performed a T-test comparing mean baseline severity scores in patients with vs. without 50% improvement, stratified by treatment status (Table 4). The absolute differences in baseline severity by 50% improvement status were small for each group. For example, the absolute difference in the combined group was 0.7 points which is below the a priori MCID of 5 points, and indicates that the differences were not clinically significant for any of the sub-groups. The between-group difference (i.e. patients with vs. without 50% improvement) among subjects receiving investigational treatment was 2.1 points, or an effect size of 0.21 – also below an MCID using the rules of Cohen.16

Prospective Construct Validity of Binary Response and 50% Improvement

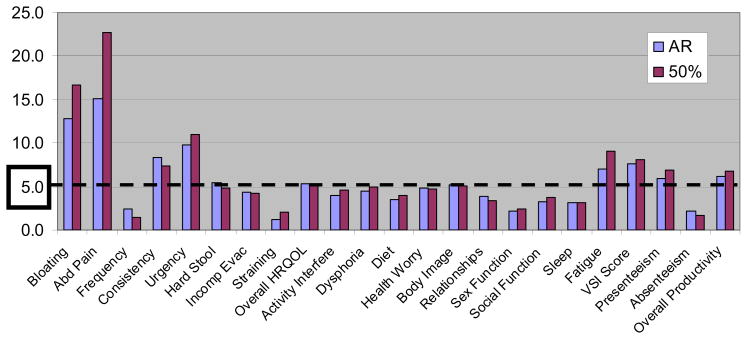

The prospective construct validity of the binary endpoint was first tested by performing a series of T-tests to compare mean difference in difference (DID) scores for each symptom or construct in Table 2, stratified by binary response status. The full results of the 23 T-tests are presented in the Appendix. All of the T-tests yielded p values <0.0005, indicating that the binary response endpoint was able to discriminate between groups for all 23 tested constructs. Using the 50% improvement endpoint, the same analysis found all T-tests yielded p values <0.007. Therefore, both the binary and 50% improvement endpoints were able to discriminate between groups for all tested constructs.

To measure the clinical relevance of these results, we overlaid a 0.5 SD benchmark for each T-test, as described in the methods. Figure 3 portrays the absolute difference in difference across all 23 constructs, placing the results of the two endpoints side-by-side. The dashed line marked the threshold for clinical relevancy. Visual inspection of Figure 3 reveals that both endpoints performed almost equivalently in terms of achieving clinically relevant separation between groups. The largest difference in difference scores were achieved in separating patients by abdominal bloating and pain, with the 50% improvement definition achieving numerically higher discriminant validity than the binary response definition. Both endpoints achieved clinically relevant differences for stool consistency, urgency, hard stool, overall HRQOL, body image, fatigue, VSI scores, presenteeism, and overall work productivity. In contrast, neither endpoint clinically separated groups by stool frequency, incomplete evacuation, straining, activity interference, diet, relationships, sexual function, social function, sleep, or absenteeism.

Figure 3.

“Difference in Difference” (DID) Scores Stratified by Response Status. The Figure depicts two series of data: one for adequate relief (AR), and one for 50% improvement in severity. The data are stratified by 23 variables, including bowel symptoms, HRQOL domains, and work productivity domains. Each bar reveals the mean DID scores for each variable between responders and non-responders, stratified by responder definition. The higher the DID the better the discriminant validity. For example, using the AR response definition, the mean DID abdominal pain score between responder groups was 15. In contrast, using the 50% improvement definition, the mean DID score between groups was 22.5. Both bars exceed the threshold for “clinical significance” depicted by the dashed line at 5-points (i.e. half standard deviation MCID definition).

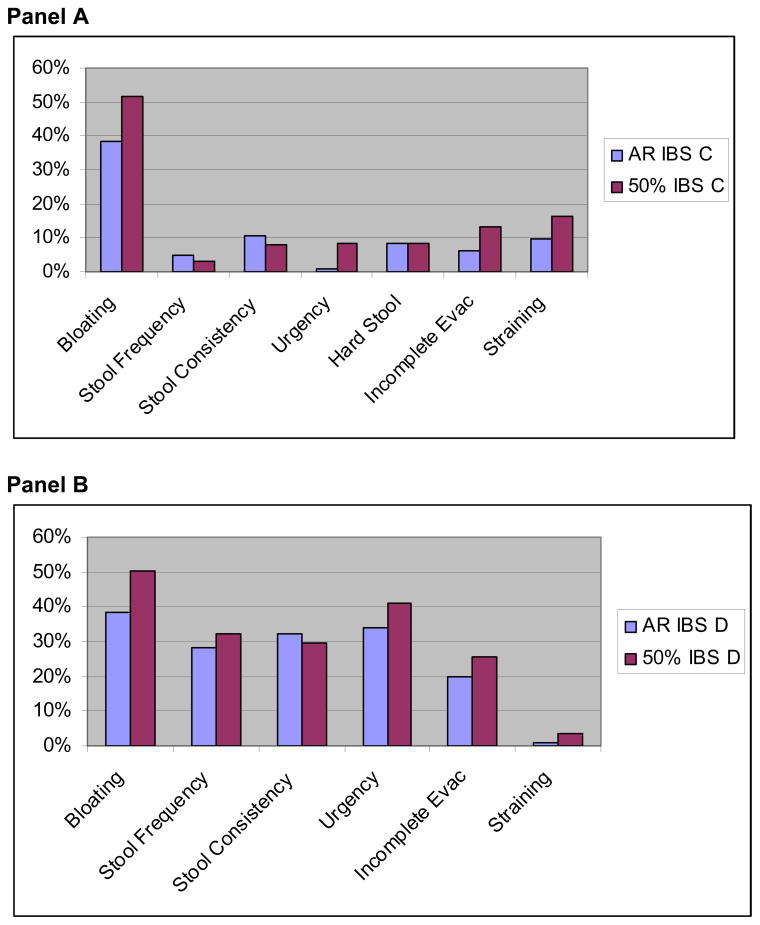

In addition, we also measured clinical relevancy by calculating the proportion of patients in each group achieving an MCID, using the 0.5 SD metric for each variable. Figure 4A portrays the results in IBS-C group. In this group, both endpoints provided maximal discriminant ability for bloating, with lower discriminant ability of both endpoints for all other symptoms in the IBS-C group, with the smallest values in the stool frequency comparisons. Compared to the binary response endpoint, the 50% improvement definition achieved a higher numerical spread between groups for bloating, urgency, hard stool, incomplete evacuation, and straining. In contrast, the binary response endpoint achieved slightly improved discriminant ability for stool frequency and consistency.

Figure 4.

Proportion of Patients Achieving an MCID for Individual Bowel Symptoms – AR vs. 50%. Panel A provides data in the IBS-C sub-population, and Panel B provides data in the IBD-D sub-population. Each bar represents the results of an individual 2×2 table, and depicts the difference in MCID achievement between responders and non-responders. For example, 38% more IBS-C patients in the binary response group achieved an MCID in bloating vs. those not achieving a binary response. In contrast, 52% more IBS-C patients in the 50% improvement group achieved an MCID in bloating vs. those not achieving 50% improvement.

Figure 4B portrays the results in IBS-D group. The data reveal that both endpoints provided maximal discriminant ability for bloating and urgency. Unlike in the IBS-C subgroup, the discriminant ability of both endpoints remained sizeable (20% spread or higher) for all symptoms except straining, which itself is not a cardinal symptom of IBS-D, and therefore of unclear significance in this patient subgroup.

DISCUSSION

This pooled analysis was motivated by questions regarding the validity of traditional IBS endpoints, with particular focus on binary endpoints.5 The Rome Foundation Outcomes and Endpoints Committee combined data from over 9000 patients from 12 randomized controlled drug trials involving 5 separate investigational treatments with different mechanisms of action. Our goal was to leverage the power of this harmonized database to explicitly test key psychometric properties of binary endpoints, and to compare the performance of binary endpoint with the “50% improvement” criterion suggested as an alternative metric.5

Regarding the impact of baseline severity on endpoint performance, we found that the relationship between severity and binary responder status was not statistically significant in the adjusted analysis, and the relationship did not meet criteria for clinical significance, regardless of the resulting p-values. In contrast, we found that the “50% improvement” criterion for pain severity was significantly associated with baseline severity in the adjusted analysis, particularly for patients receiving investigational treatment. However, the clinical relevance of the relationship with baseline severity was minimal across all treatment groups. The observation that there is not an important relationship between baseline pain severity and response status, either defined with a binary endpoint or “50% improvement” criterion, is consistent with previous studies6–8 and contrary to the results of Whitehead et al.5 It is possible that the analyses reported in a community sample by Whitehead et al. included subjects from a health maintenance organization with a broader range of IBS symptom severity than the subjects included in the clinical trials summarized in this pooled analysis.

We further tested the construct validity of both endpoints against a range of IBS illness domains. In short, we found that both the binary response and 50% improvement endpoints reveal excellent construct validity across a wide range of variables (Figure 3). Both endpoints are able to detect MCIDs in key bowel symptoms, including bloating, abdominal pain, consistency, urgency, and hard stool. They are also able to detect MCIDs in worker productivity, visceral hypersensitivity scores, and fatigue scores. Whereas both endpoints are able to detect MCIDs for overall HRQOL, they are less capable of detecting MCIDs for the individual HRQOL components. Thus, both endpoints track with key components of IBS illness severity, neither is clearly superior over the other, and both work as expected.

We found that both the binary response and 50% improvement endpoints performed similarly in discriminating between MCID responders and non-responders for bowel symptoms in IBS sub-groups. Of note, both endpoints appear to provide better discrimination in the IBS-D than IBS-C subgroups (Figures 4A and 4B). This has potential implications for studies that seek to establish differences in response rates between treatment and placebo groups. The data suggest that both endpoints may be better suited for the IBS-D population. In IBS-C patients, the percentage achieving an MCID is numerically smaller, suggesting that more sensitive endpoints might be necessary for the IBS-C groups. A corollary is that drugs failing to show large effect sizes in this population might have been hampered by the psychometric properties of the binary endpoints. Further research should aim to test current and future endpoints in both IBS-C and IBS-D subgroups, and to establish whether the psychometric properties are similar or different in these phenotypically distinct populations. It is possible that a “one size fits all” approach to endpoints may not apply in IBS: different sub-groups may be better captured with tailored endpoints. This finding raises the question of whether clinical trialists should employ different endpoints for IBS-C vs. IBS-D. This would represent a notable change in our approach to endpoint measurement in IBS. Our study is unable to determine why endpoints may behave differently by sub-group; instead it merely raises the question. Future research should aim to understand why this might be. In the meantime, our finding suggests that further research should carefully evaluate endpoint performance in both groups separately.

These data add to previous conclusions that global binary endpoints are useful in IBS,2 based on the collective clinical trial experience in almost 20,000 IBS patients with at least five different medications (alosetron, cilansetron, tegaserod, lubiprostone, dextofisopam) tested with binary endpoints. Binary endpoints have been devalued given the relative lack of psychometric validation until now. Yet even before this pooled analysis, previous investigators demonstrated that binary endpoints were acceptable to patients, and that binary responses were driven by the patients’ most bothersome symptom.18, 19 Based on a systematic review of 12 pre-specified criteria, Bijkerk et al. concluded that the weight of evidence was in favor of using “adequate relief” – a binary endpoint – among the different available endpoints used in IBS trials.3 Drugs that are effective, based on the binary response endpoints, were also found to improve general or disease-specific quality of life.20 Based on these collective data, the Rome III guidance on IBS clinical trials endorsed using a global measure that integrates the symptom data into a single numerical index, measured either as a binary endpoint or a continuous integrative symptom questionnaire such as the IBS-SSS.10 We have now expanded and confirmed these collective results and conclusions by demonstrating excellent construct validity of the binary endpoints with a wide range of patient symptoms, psychosocial illness experiences, visceral sensitivity reporting, HRQOL, and even work productivity. Moreover, we have found that the performance of a binary endpoint is psychometrically equivalent to monitoring pain severity on a continuous scale, and adopting the “50% improvement” criterion recommended by Whitehead et al.5

Based on our data, coupled with extensive pre-existing data supporting the validity of the binary endpoints, it is reasonable to conclude that use of binary endpoints in IBS clinical trials is rational and valid. No endpoint can be fully validated; establishing the validity of a PRO is an ongoing and iterative effort. But our results add to this effort and further confirm that binary endpoints get the job done – they work as expected. This is an important conclusion because it supports the validity of existing studies, highlights the efficacy of therapies originally tested in trials employing binary endpoints, and indicates that future studies could also use these endpoints without undue concern.

Our study has several strengths. First, the sample size of this analysis is large, and the use of pooled patient-level data is a more powerful method of synthesizing multiple studies than conventional meta-analysis. This provides considerable power to investigate the psychometric properties of IBS endpoints. Second, because we are cognizant that large sample sizes can yield statistically significant relationships that are not clinically relevant, we overlaid a priori criteria for clinical relevance, and reported results that were both statistically significant and clinically relevant. Third, we conducted sub-analyses across key groups, including IBS sub-groups (i.e. IBS-C vs. IBS-D) and treatment groups (active vs. placebo). This allows us to generalize our results across different populations. Finally, we measured a range of key psychometric properties using multiple clinical anchors. This allows us to triangulate the validity of the endpoints from several perspectives.

Our study has limitations. First, as with any meta-analysis, we were faced with combining disparate data from different studies, each with unique inclusion and exclusion criteria, disease characteristics, and endpoint evaluations. However, we have been careful to acknowledge these variations, as described in our methods section, and have attempted to balance the power of harmonizing large datasets with the inevitable methodological shortcomings of combining disparate data. Second, it is possible that patients in randomized controlled trials are systematically different from other populations of IBS patients. However, this is precisely the population in question, since the current main use of PRO measures is for clinical trials to test the effect of pharmacologic interventions in IBS. As PROs continue to penetrate into everyday clinical practice, further validation studies will be necessary in non-clinical trial populations. Third, our measure of “IBS severity” was limited to “pain severity.” We were unable to employ multi-attribute severity scales like the IBS-SSS, because there were inadequate data for this purpose. However, pain is a cardinal symptom of IBS,11, 12 and it drives overall illness severity more, on average, than any other symptom. In short, there is sufficient rationale and precedent to use pain severity as a surrogate for overall IBS illness severity, as we have done here.

In conclusion, this large patient-level meta-analysis reveals that both the binary and 50% improvement endpoints are equivalent in their psychometric properties. Neither is impacted by baseline severity, and both demonstrate excellent construct validity. They appear optimized for the IBS-D population, but are also valid in IBS-C.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support/Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Spiegel is supported by a Veteran’s Affairs Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Career Development Transition Award (RCD 03-179-2), the CURE Digestive Disease Research Center (NIH 2P30 DK 041301-17), and NIH Center Grant 1 R24 AT002681-NCCAM. Dr. Spiegel has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, McNeail Consumer, Novartis, Prometheus, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and TAP Pharmaceuticals, and has received grant support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Salix, and Takeda. Dr. Camilleri has served as a consult for Glaxo SmithKline, and has received research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals and Novartis. Drs. Fehnel and Mangel are employees of RTI Health Solutions. Dr. Chey is a consultant for Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Solvay, and Ironwood, and is on the speaker’s bureau of Novartis. Dr. Talley is a consultant for Astellas Pharma Inc. US, AstraZeneca, Centocor, Eisai, Elsevier, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Focus, Gilead, In2MedEd, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, McNeil Consumer, Medscape, Meritage Pharma, Metabolic Pharma, Microbia Inc, Novartis, Optum HC, Salix, SK Life Sciences, Steigerwald, The Journal of Medicine, Therevance, and Wyeth, and received grant support from Glaxo SmithKline, Dynogen, and Tioga.

We wish to acknowledge Drs. Emeran Mayer and Hashem El-Serag as non-author members of the Rome Foundation Endpoints Working Group. We further acknowledge Carlar Blackman of the Rome Foundation for her administrative and logistical support of this research project, and Dr. Douglas Drossman for his stewardship of the Rome Foundation. We also wish to thank the pharmaceutical companies that donated their time and data to assist the Working Group in successfully completing this project.

Abbreviations

- AR

adequate relief

- C

constipation

- CI

confidence interval

- D

diarrhea

- HRQOL

health related quality of life

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- IBS-SSS

IBS severity symptom score

- LOCF

last observation carried forward

- MCID

minimal clinically important difference

- OR

odds ratio

- PRO

patient resported outcome

- VSI

visceral sensitivity index

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions contained herein are the sole views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Veteran Affairs.

Participating Organizations: The paper is the result of the Rome Foundation Outcomes and Endpoints Working group (Chair M. Camilleri MD) whose members (listed as authors) are responsible for the conduct, analysis and interpretation of the data. The following companies provided data in kind for this meta-analysis: AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Ironwood, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Rotta Pharmaceuticals, and Solvay. The data from Rotta Pharmaceuticals lacked necessary elements for purposes of our analysis, and was therefore unable to be employed in this study. The authors and Rome Foundation maintained complete control of all data and analyses. This study was supported by the Rome Foundation. The Rome Foundation wishes to thank the participating pharmaceutical companies for their donated time and willingness to contribute data to this effort.

Authors’ Role in Manuscript: Brennan Spiegel and Roger Bolus were involved in study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, statistical analysis, and study supervision. Michael Camilleri was involved in study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, obtaining funding, and study supervision. Viola Andresen, William Chey, Sheri Fehnel, Allen Mangel, Nicholas Talley, and William Whitehead were involved in study concept and design, interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burke LB, Kennedy DL, Miskala PH, Papadopoulos EJ, Trentacosti AM. The use of patient-reported outcome measures in the evaluation of medical products for regulatory approval. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:281–3. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camilleri M, Mangel AW, Fehnel SE, Drossman DA, Mayer EA, Talley NJ. Primary endpoints for irritable bowel syndrome trials: a review of performance of endpoints. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:534–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bijkerk CJ, de Wit NJ, Muris JW, Jones RH, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW. Outcome measures in irritable bowel syndrome: comparison of psychometric and methodological characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:122–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangel AW, Hahn BA, Heath AT, Northcutt AR, Kong S, Dukes GE, McSorley D. Adequate relief as an endpoint in clinical trials in irritable bowel syndrome. J Int Med Res. 1998;26:76–81. doi: 10.1177/030006059802600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Levy RL, Feld AD, VonKorff M, Turner M. Reports of “satisfactory relief” by IBS patients receiving usual medical care are confounded by baseline symptom severity and do not accurately reflect symptom improvement. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1057–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leventer SM, Raudibaugh K, Frissora CL, Kassem N, Keogh JC, Phillips J, Mangel AW. Clinical trial: dextofisopam in the treatment of patients with diarrhoea-predominant or alternating irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, Katz LA, Gudleski GD, Holroyd K. Self-administered cognitive behavior therapy for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome: clinical efficacy, tolerability, feasibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ameen VZ, Health AT, McSorley D, Spiegel BM, Chang L. Global measure of adequate relief predicts clinically important difference in pain and is independent of baseline pain severity in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:A140. (abstract 941) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irvine EJ, Whitehead WE, Chey WD, Matsueda K, Shaw M, Talley NJ, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ. Design of treatment trials for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1538–51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lembo A, Ameen VZ, Drossman DA. Irritable bowel syndrome: toward an understanding of severity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:717–25. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegel B, Strickland A, Naliboff BD, Mayer EA, Chang L. Predictors of Patient-Assessed Illness Severity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drossman D, Morris CB, Hu Y, Toner BB, Diamant N, Whitehead WE, Dalton CB, Leserman J, Patrick DL, Bangdiwala SI. Characterization of health related quality of life (HRQOL) for patients with functional bowel disorder (FBD) and its response to treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1442–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labus JS, Mayer EA, Chang L, Bolus R, Naliboff BD. The central role of gastrointestinal-specific anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome: further validation of the visceral sensitivity index. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:89–98. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802e2f24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fehnel SJJ, Kurtz C, Mangel A. Assessing global change and symptom severity in subjects with IBS: qualitative item testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:S483. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon S, Ameen V, Bagby B, Shahan B, Jhingran P, Carter E. Validation of irritable bowel syndrome Global Improvement Scale: an integrated symptom end point for assessing treatment efficacy. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1317–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1024159226274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Serag HB, Olden K, Bjorkman D. Health-related quality of life among persons with irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1171–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.