Abstract

Two Arabidopsis xylosyltransferases, designated RGXT1 and RGXT2, were recently expressed in Baculovirus transfected insect cells and by use of the free sugar assay shown to catalyse transfer of D-xylose from UDP-α-D-xylose to L-fucose and derivatives hereof. We have now examined expression of RGXT1 and RGXT2 in Pichia pastoris and compared the two expression systems. Pichia transformants, expressing soluble, secreted forms of RGXT1 and RGXT2 with an N- or C-terminal Flag-tag, accumulated recombinant, hyper-glycosylated proteins at levels between 6 and 16 mg protein • L-1 in the media fractions. When incubated with 0.5 M L-fucose and UDP-D-xylose all four RGXT1 and RGXT2 variants catalyzed transfer of D-xylose onto L-fucose with estimated turnover numbers between 0.15 and 0.3 sec-1, thus demonstrating that a free C-terminus is not required for activity. N- and O-glycanase treatment resulted in deglycosylation of all four proteins, and this caused a loss of xylosyltransferase activity for the C-terminally but not the N-terminally Flag-tagged proteins. The RGXT1 and RGXT2 proteins displayed an absolute requirement for Mn2+ and were active over a broad pH range. Simple dialysis of media fractions or purification on phenyl Sepharose columns increased enzyme activities 2-8 fold enabling direct verification of the product formed in crude assay mixtures using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Pichia expressed and dialysed RGXT variants yielded activities within the range 0.011 to 0.013 U (1 U = 1 nmol conversion of substrate • min-1 • µl medium-1) similar to those of RGXT1 and RGXT2 expressed in Baculovirus transfected insect Sf9 cells. In summary, the data presented suggest that Pichia is an attractive host candidate for expression of plant glycosyltransferases.

Keywords: Plant cell wall, Glycosyltransferase, Free sugar assay, Protein expression, Pichia pastoris

Introduction

A main challenge in the post genomic era is the assignment of function to open reading frames with unknown function. The plant cell wall (CW) consists of numerous complex carbohydrate polymers and glycoproteins. Although the sugar composition of the plant CW components is largely resolved, less is known with respect to the corresponding biosynthetic machinery. The Carbohydrate Active EnZyme (CAZy) database [1–3], (http://afmb.cnrsmrs.fr/CAZY/index.html) currently lists 448 sequences for Arabidopsis thaliana as proven or putative glycosyltransferases (GTs). CAZy classifies GTs into 91 families, 40 of which are represented in Arabidopsis. So far, thirteen non-cellulosic/callosic CW GT activities have been successfully heterologously expressed and biochemically characterized (Cf. reviews by e.g. [4–7]). The GTs responsible for the synthesis of cellulose and callose are multi membrane spanning glucan synthases located at the plasma membrane. The cellulose synthases belong to family GT2, which also comprises the cellulose synthase like genes, Csl. Four genes from this group have been shown by heterologous expression and biochemical assay to encode β-1,4-mannan synthases [8, 9]. One gene product was shown to possess β-1,4-glucan synthase activity in raw cell extracts [10] and two barley CslF genes, were shown to confer production of mixed linkage (1-3;1-4)-β-D-glucan polymers when stably expressed in A. thaliana [11].

The GTs responsible for the synthesis of the CW polymers hemicellulose and pectin, and of the various CW-glycoproteins are thought primarily to be Golgi localized, where the majority of these GTs adopt the type II structure comprising a short N-terminal cytoplasmic tail followed by a single trans membrane spanning domain (TMD), and facing the lumen a stem region of varying length, followed by the large C-terminal globular domain, possessing the catalytic activity.

Of the estimated more than 200 type II GTs believed to participate in plant CW synthesis, nine, eight from A. thaliana and one from fenugreek, have been successfully expressed with the accompanying in vitro activity demonstrated [11–21]. Three of the GTs were expressed in P. pastoris, and the remaining GTs in African Green Monkey Kidney Cells (COS cells), in the human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293, in baculovirus transfected insect cells, and in Nicotiana benthamiana (see Table 1). The rather limited success of heterologously expressing GTs may be ascribed to mismatch between biochemical assay and the native activity or failure of the expressed protein to accumulate to detectable levels, incorrect folding, or improper secondary modifications.

Table 1.

Heterologously expressed non-cellulosic/callosic plant CW biosynthetic GTs with proven biochemical activity

| Enzyme Identifier | Monosaccharide transferred | CW component | Enzyme topology | CAZY GT fam | Portion of GT expressed | Host organism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtFT1 | L-fucose | XyG | Type II | 37 | FL | COS cells | [12, 13] |

| GalT of fenugreek | D-galactose | GM | Type II | 34 | FL and S (secreted) | Pichia pastoris | [14] |

| AtXT1 & -2 | D-xylose | XyG | Type II | 34 | FL | Pichia pastoris, Drosophila S2 and Baculo virus Sf21 cells | [15, 16] |

| AtMur-3 | D-galactose | XyG | Type II | 47 | FL | Pichia pastoris | [17] |

| ManS of Gua and AtCslA2,7,9 | D-mannose | GM | MMS | 2 | FL | soybean somatic embryos and Drosophila (S2) cells | [8, 9] |

| mixed linkage glucan syntase OsCSLF2 and OsCSLF4 | D-glucose | Mixed linkage glucan | MMS | 2 | FL | Arabidopsis thaliana | [11] |

| AtGAUT1 | D-galacturonic acid | HGA | Type II | 8 | FL | HEK293 | [18] |

| AtRGXT1, -2 & -3 | D-xylose | RG-II | Type II | 77 | S (secreted) | Baculo virus Sf9 cells, Pichia pastoris | [19, 20] |

| XyGS of Tropaeolum majus and AtCSLC4 | D-glucose | XyG | MMS | 2 | FL | Pichia pastoris | [10] |

| XGD1 | D-xylose | XGA | Type II | 47 | FL | N. benthamiana | [21] |

The table summarizes non-cellulosic/callosic CW GTs, which have been heterologously expressed with the enzymatic activity demonstrated. While the full length AtMUR3 [17] and AtXT1 [15] proteins were expressed with a C-terminal and a N-terminal poly histidine (His) tag, respectively, the soluble secreted versions of RGXT1 & RGXT2 contained an N-terminal His(6) tag followed by a T7 tag [19] and the soluble secreted version of RGXT3 contained an N-terminal Flag-tag [20]. All other proteins were expressed either as full length or soluble proteins without tags

At Arabidopsis thaliana;HEK293 human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293;Drosophila S2 Drosophila Schneider 2;COS cells African Green Monkey Kidney Cells;CSL cellulose synthase like;FL Full Length;FT1 fucosyltransferase-1;GalT galactosyltransferase;GAUT galacturonosyltransferase;GAX glucuronoarabinoxylan;HGA homogalacturonan;RG-II rhamnogalacturonan II;GM galactomannan;ManS mannan backbone syntase;MMS Multi Membrane Spanning;Mur-3 ‘Muros’-3;Os Oryza sativa;Type II Type II membrane spanning protein;S Soluble;RGXT RhamnoGalacaturonan XylosylTransferase;Sf21 Spodoptera frugiperda 21 cells;XGA xylogalacturonan;XyG xyloglucan;XyGS xyloglucan syntase;XT1 and -2 xylosyltransferase-1 and -2

Expression systems that rely on higher plant cells may overcome some of these problems. The GT can be targeted in its full length, membrane-anchored form to the Golgi vesicles. This approach largely eliminates problems with incorrect folding and inadequate posttranslational modifications, and the assay may rely on required but unidentified endogenous factors and even utilize acceptor molecules present in the GT containing microsomal fraction. Background activities may be an issue in a higher plant system, and preparing stable transformants is a slow process, often too slow to be practical for screening purposes. A transient expression system using Agrobacterium mediated transient transformation of N. benthamiana [22] shows some promise of solving the low through-put issue with stable transformants (JK Jensen, BL Petersen, N Geshi, P Ulvskov, HV Scheller, unpublished results).

Expression in prokaryotes, having no support for posttranslational processing, represents the other extreme. The relative high number of successfully expressed GTs of CAZy GT family 1 in E. coli [23] may primarily be ascribed to the fact that this GT family incorporates soluble enzymes acting on relatively low molecular mass acceptor substrates. Eukaryotic hosts are usually considered for human and other mammalian gene products, see e.g. review [24], and none have emerged as the ideal system, and likewise for higher plant gene products, all of the relatively few expression systems used at present are far from guaranteeing production of correctly folded and processed gene-products.

In recent years, the methylotropic yeast P. pastoris has become increasingly popular as expression host (for a comprehensive introduction to expression of heterologous proteins in P. pastoris see reviews [25, 26] and list of proteins expressed in P. pastoris (http://faculty.kgi.edu/cregg/index.htm)). In the present study we have expressed two A. thaliana α-1,3-xylosyltransferases, RGXT1 and RGXT2, implicated in the xylosylation of the internal fucose moiety of the A-chain of pectic rhamnogalacturonan II (RG II) [19], in P. pastoris and made a first characterization of the enzymes. Using the P. pastoris system, we have addressed a number of problems to consider with any eukaryotic expression system: post translational modification (especially glycosylation), activity in relation to the introduction and placement of tags, and the occurrence of interfering substances in the medium, a problem that applies to many liquid culture-based systems. On a µl to µl medium basis the P. pastoris system provides similar activity yields as compared to the baculovirus insect cell system, thus making the P. pastoris system a highly competitive system to be used e.g. in large-scale gene discovery efforts.

Materials and methods

Prediction servers

Prediction of N-glycosylation sites and TMDs in RGXT1 (At4g01770), RGXT2 (At4g01750), and RGXT3 (At1g56550), were done using the NetNGlyc (using 0.5 as threshold) and TMHHM servers at Center for Biological Sequence Analysis (CBS, http://www.cbs.dtu.dk).

Cloning of the soluble parts of RGXT1 and RGXT2 in to the pPiczαA vector

Full length RGXT1 and RGXT2 cDNAs were obtained and cloned as described in [19]. Fragments corresponding to the soluble forms of the proteins, i.e. amino acid residues 56-361 of RGXT1 and 53-367 of RGXT2, were PCR amplified using the following five primer-sets:

PF-sRGXT2-5: 5′-gaattcATGGATTACAAGGACGACGACGACAAGcacgtgccttggcccggatctcctttgtt-3,

PF-sRGXT2-3: 5′-gcggccgcttactgcaatttccctaatgga-3’;

PsRGXT2-F-5: 5’-gaattcccttggcccggatctcctttgtt-3’,

PsRGXT2-F-3: 5’-gcggccgcttaCTTGTCGTCGTCGTCCTTGTAATCCATcacgtgctgcaatttccctaatgga-3’,

PF-sRGXT1-5: 5’-cacgtgtctcccttattcctgtttcca-3’,

PF-sRGXT1-3: 5’-gcggccgcttactctaatttccctaatggag-3’

PsRGXT1-F-5: 5’-gaattctctcccttattcctgtttcc-3’,

PsRGXT1-F-3: 5’-cacgtgctctaatttccctaatggag-3’;

where capital letters encode the Flag-Tag (’MDYKDDDDK’, Invitrogen), the underlined sequences denote PmlI, NotI and EcoRI restriction sites and s and F denote the soluble part of the protein and Flag-tag, respectively (as read from the N-terminus to the C-terminus of the fusion proteins). Initially, F-sRGXT2 and sRGXT2-F, containing an N-terminal and a C-terminal Flag-tag, respectively, were PCR amplified, subcloned, sequenced and finally cloned into the pPiczαA vector (Invitrogen) using the 5’ and 3’ restriction sites, EcoRI and NotI, respectively, introduced by the primerpair PF-sRGXT2-5 & PF-sRGXT2-3 or the primer-pair PsRGXT2-F-5 & PsRGXT2-F-3, producing the constructs F-sRGXT2-pPiczαA and sRGXT2-F-pPiczαA, respectively. Subsequently, F-sRGXT1-pPiczαA and sRGXT1-F-pPiczαA (sRGXT1 with either an N-terminal or C-terminal fused Flag-tag) were made by replacing the PmlI-NotI (5’-3’) insert or the EcoRI-PmlI (5’-3’) insert of F-sRGXT2-pPiczαA and sRGXT2-F-pPiczαA, respectively. PCR was performed in 50 μl reaction volumes using the Expand High Fidelity system (Beohringer Ingelheim, Copenhagen, Denmark) with the cycle parameters: 3 min 97°C (Denaturation), 30–35 cycles: 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s and 68°C for 1’ followed by 12 min at 72°C. All PCR amplifications were cloned into the pCR®2.1 vector using the TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and the authenticity of the inserts was verified by sequencing, before the final cloning into the end vector (pPiczαA with/without an N-terminal or C-terminal Flag- tag).

Cloning and expression of F-sRGXT3 are described in [20].

Scoring, growth and induction of the highest expressed P. pastoris transformants

Linearized DNA of the constructs F-sRGXT1-pPiczαA, sRGXT1-F-pPiczαA, F-sRGXT2-pPiczαA and sRGXT2-F-pPiczαA were transformed into the P. pastoris KM71H strain by electroporation, plated on yeast extract peptone dextrose sorbitol plates containing zeocin (100 μg • mL-1), and incubated for 2–3 days at 30°C as described in Invitrogen Life technologies: The Pichia pastoris Expression system. In order to score the highest expressing transformants, 10 transformants of each construct were grown in 5 ml cultures and expressed as described below for two days at 30°C, where after the medium fraction was subjected to western blot analysis.

In expression studies, 10 mL of buffered complex glycerol medium supplemented with 100 μg • mL-1 zeocin were inoculated with the highest expressed transformant of each construct and grown in an incubator at 28°C, 280–300 rpm, ON until the OD600 reached a value between 2 and 6. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and re-suspended in buffered 50 mL complex methanol medium to an OD600 of 1.0 in 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks. Incubation was continued for a total of 120 h at 20°C, 280–300 RPM, and at 24 h intervals, methanol was added to 0.5% (v/v) final concentration. At each time point 1 ml fractions were collected and the media fractions were recovered by centrifugation, frozen in liquid N2 and stored at -80°C. At day five (120 h of induction) cells were pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatant (medium fraction) was collected for further processing or analysis (see below). The presence of 1 mM DTT in xylosyltransferase assays (see below) resulted in slightly but reproducibly reduced activities (data not shown). More than one freeze thaw cycle resulted in detectable loss of activity.

SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting analysis, and quantifications of protein levels

Proteins were dissolved in NuPAGE Antioxidant and NuPAGE Loading Sample Buffer (LDS) from Invitrogen (1 : 1), boiled for 5–10 min, spun down and separated on SDS–containing 4–12% polyacrylamide Tricine gels (Invitrogen) using the MOPS-SDS system (Invitrogen) as running buffer. Electrophoresis was performed with the settings: 200 V, 150 mA, 200 W, 1 h. Molecular markers were the SeeBlue Plus2 Pre-Stained Standard (Invitrogen) and MagicMark XP Western Standard (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to activated (99.9% EtOH) polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (0.2 μm pore size, Invitrogen) using semi-dry electro blotting (settings: 200 V, 150 mA, 200 W, 1 h). Following transfer the PVDF membranes were washed 2 × ddH2O, 2–3’, blocked in 1 × TBS 3% skimmed milk powder (SKP), 30’, washed in 1 × Tris Buffered Saline (1 × TBS), pH 8.0, probed with mouse Anti Flag M2 monoclonal Antibody (Sigma Aldrich, Denmark) in a 1:1000 dilution in 1 X TBS 3% SKP overnight at 4°C under mild shaking, washed in 1 × TBS, probed with rabbit anti mouse peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark) in a 1:1,000 dilution in 1 X TBS 3% SKP and washed 8 × 3’ in 1 × TBS with 0.05% Tween20 and finally placed in 1 × TBS. Chemi-luminiscence was monitored using the Super Signal Enhanced Chemical Luminiscence (ECL, Copenhagen, Denmark), which was visualized on a BioSpectrum (UVP BioImaging Systems, Upland, California, USA) and semi quantified using the LabWorks program. Amount of Flag-tagged GTs were semi-quantified by comparison to standard curves of dilution series of 5 ng, 10 ng, 20 ng and 30 ng Amino-terminal Bovine Serum Albumin Protein Met-FLAG (BAP) (468 a.a., 49.4 kDa) from Sigma. Expression levels of secreted T7-tagged RGXT1 and RGXT2 (39.9 and 40.7 kDa, respectively) in the baculovirus system were estimated by co-electrophoresis and blotting of a dilution series of purified T7 tagged Muc1 3 1/2 tandem repeat (10.2 kDa). Immuno detection of the T7-epitope was carried out using a mouse monoclonal antibody directed against the T7-tag conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Cat. No. 69048-3, Novagen, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in a 1:1000 dilution. An SDS-PAGE gel including both the BAP and the Muc1-standard series was run and Coomassie stained to verify the estimated amounts. Total protein in the media fractions was estimated using the Bradford Reagent (Sigma).

Purification of expressed proteins

In order to identify the optimal (NH4)2SO4 concentration for binding to phenyl Sepharose, 3 × 5 ml F-sRGXT2 containing media were incubated with 25%, 50% 75% saturated (NH4)2SO4, respectively, for 1–2 h on ice. The mixtures were spun down (5000 × g, 4°C, 10 min) and the three supernatants were applied on columns containing 300 μl CL-4B phenyl Sepharose® (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Each column was washed with five column volumes of 50% (NH4)2SO4 and eluted with 3 × 1.5 ml 2.5 mM ammonium formate, pH 7.6. Eluates and precipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. From this experiment it was evident that F-sRGXT2 precipitates at (NH4)2SO4 saturation higher than 50% and lower than 75% and that the phenyl Sepharose binds F-sRGXT2 in 50% saturated (NH4)2SO4. In scaled up experiments 16 ml GT containing medium and 16 ml 100% (NH4)2SO4 were mixed and applied to 2 ml phenyl Sepharose, which was eluated in 2 × 2 ml 2.5 mM ammonium formate, pH 7.5. Crude media fractions (5 – 10 ml) and phenyl Sepharose eluates were dialyzed in 5 L 25 mM ammonium formate, pH 7.5, using Medicell MWCO 12-14000 Da dialysis bags (KEBO Lab) for 3 h at 4°C, and continued overnight with 5 L of fresh dialysis buffer.

Deglycosylation

Purified and dialysed proteins (9.3 µg F-sRGXT1, 7.1 µg sRGXT1-F, 10.6 µg F-sRGXT2 and 6.5 µg sRGXT2-F) were mixed with 20 µl 5 × incubation buffer (0.25 M sodium phosphate, pH 7), 2 µl Peptide:N-glycanase F [5 U • ml-1] and 2 µl O-glycanase [1.25 U • ml-1] in total volumes of 100 µl according to Glyko Reactionlab AS (Lynge, Denmark). Two aliquots of 33 µl of each mixture were incubated 20 h at 25°C and 37°C, respectively. Aliquots (10 µl) of each sample were used in the xylosyltransferase assay using 0.5 M L-fucose as acceptor. Aliquots (2 µl) of the remaining samples were subjected to immunoblotting as described above.

The xylosyltransferase assay

Standard xylosyltransferase assay was carried out according to the general free sugar assay [28] in 50 µl reaction mixtures containing 25 mM ammonium formate, pH 7.5, 10 mM MnCl2, 0.75 μl UDP-α-[14C]-D-xylose (9.8 GBq/mmol, 264 mCi/mmol, 10 nCi/μl, 0.75 μl ~ 12-14000 CPM) (NEN, Boston MA, USA), 100 µM UDP-α-D-xylose (CarboSource (Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, Athens, Georgia, USA)), 0.5 M L-fucose and 5 µl, except when otherwise stated, of the enzyme in question, which were incubated for 1 h at 30°C. Unincorporated UDP-α-[14C]-D-xylose and UDP-α-D-xylose were removed by passing the reaction mixture through a Dowex-1 anion exchanger (Sigma-Aldrich Denmark A/S) and the radioactivity in the flow through was determined by scintillation counting.

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry of assay product

ESI-MS data were obtained by use of a ThermoFinnigan connected to an AXP-MS, Dionex. The mass spectrometer was run in positive mode with 0.1% HCOOH in 50 mM NaCl solution. Samples were prepared as described under xylosyltransferase assay, but without use of UDP-α-[14C]-D-xylose and omitting the anion exchange step.

Mn2+ and pH dependency

Ammonium formate stock solutions (250 mM) with pHs in the range from pH 3 to 11 were prepared and standard xylosyltransferase assays were incubated at 30°C for 60 min. The pH of each assay was monitored in parallel by probing the assay mixtures on pH strips directly after incubation and confirmed to be identical to the pH of the stock solutions.

Results

Detection of heterologously expressed and secreted protein in P. pastoris

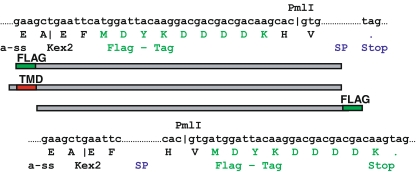

In order to enable estimation of expression levels and to evaluate effect of tags, which may influence targeting, folding and activity, a Flag-tag (’MDYKDDDDK’) was either fused to the N-terminus of the α-factor signal sequence of the pPiczαA vector or inserted into the C-terminal part of the polylinker of pPiczαA (Fig. 1). Using the two modified vectors, constructs expressing the N-terminal Flag-tagged soluble proteins F-sRGXT1, F-sRGXT2 and F-sRGXT3, and soluble C-terminal Flag-tagged proteins, sRGXT1-F and sRGXT2-F, were prepared (as read from the N-terminus to the C-terminus of the fusion proteins). RGXT3 is a new member of the RGXT family (68 and 75 % identity to RGXT1 and RGXT2, respectively), which recently was shown to possess xylosyltransferase activity with similar acceptor substrate specificities as those reported for RGXT1 and RGXT2 [20].

Fig. 1.

Design of secreted Flag-tagged soluble protein. A Flag-tag (’MDYKDDDDK’) enabling N- or C-terminal tagged fusions to the gene in question was introduced into the polylinker of the pPiczαA vector via the introduced PmlI restriction site (CAC|GTG). Kex2 and Ste2 subsiding the α-factor signal sequence designate proteolytic cleavage sites that are cleaved during passage through the secretory pathway, resulting in mature secreted N- or C-terminal Flag-tagged protein. Abbreviations: α-ss, yeast α mating factor signal sequence; GT, glycosyltransferase; TMD, transmembrane domain, Soluble protein, SP

Expression levels and estimated turnover rates

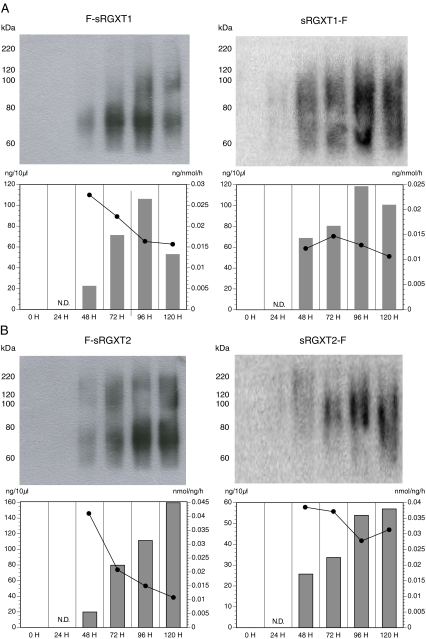

Generation and identification of the highest expressing transformants, growth conditions and induction of protein expression and harvesting of secreted recombinant protein are described in the Material and Methods section. Different temperature schemes and length of induction period were tested (data not shown). The highest expression levels, as evidenced by immunoblotting, were obtained when the P. pastoris transformants were grown at 20°C with expression periods of up to 120 h (data not shown). Using this scheme, N-terminal Flag-tagged F-sRGXT1 and F-sRGXT2 accumulated to levels of about 11 and 16 mg protein • L-1 in the media fractions, respectively (Fig. 2). When incubated with 0.5 M L-fucose as the acceptor substrate and UDP-α-D-xylose as the donor substrate, crude media fractions containing F-sRGXT1 and F-sRGXT2 were shown to catalyze the transfer of D-xylose onto L-fucose with estimated catalytic turnover numbers of ~0.2 and ~0.24 • sec-1, respectively (determined as an average over the induction period) (Fig. 2a, b). Crude media fractions containing the C-terminally Flag-tagged proteins sRGXT1-F and sRGXT2-F accumulated to levels of approximately 12 and 6 mg protein • L-1 with rather similar turnover numbers of ~0.15 and ~0.3, respectively, as obtained for the N-terminally Flag-tagged counterparts, i.e. in this case demonstrating that a native C-terminus is not required for the transferase activity.

Fig. 2.

Immunobloting and estimated specific activity. The time course of accumulation and specific activity of RGXT1 a and RGXT2 b during growth of P. pastoris cultures was determined. P. pastoris transformants were grown in 60 ml cultures under vigorous shaking (> = 280 RPM) at 20°C and samples were collected each day for 5 days. For immunoblotting 7.5 μl of the media fraction was applied on each lane (see also the Material and Methods section). Predicted MW of F-sRGXT1 & sRGXT1-F and F-sRGXT2 & sRGXT2-F: 36.534 D and 37.277 D, respectively. The amount of Flag-tagged protein in the media was estimated using Flag-tagged Bovine Serum Albumin (Flag-BSA) as reference (data not shown). Activity was measured using 0.5 M L-fucose as acceptor and radiolabeled UDP-α-D-xylose as donor in xylosyltransferase assays as described in the Material and Methods section. Estimated specific activities (estimated as an average over the induction period) in crude media fractions of F-sRGXT1, sRGXT1-F, F-sRGXT2 and sRGXT2-F were ~0.021, ~0.015, ~0.025, and ~0.03 mmol D-xylose-L-fucose dissacharide formed • mg prot-1 • h-1, respectively. Bars and • designate estimated concentrations of flag-tagged RGXT protein and specific activities, respectively, at the various time points

The four soluble RGXT1 and RGXT2 variants produced high MW smears centred around 70 to 100 kDa, when subjected to immunoblotting analysis (Fig. 2) suggesting that the secreted proteins were hyper-glycosylated. The proportion of recombinant protein, as determined by immunoblotting, to total protein of the media fractions were in the range of 35–55% for F-sRGXT1, sRGXT1-F, F-sRGXT2 and sRGXT2-F, and more than 70% in case of F-sRGXT3 (data not shown).

Optimization of activity

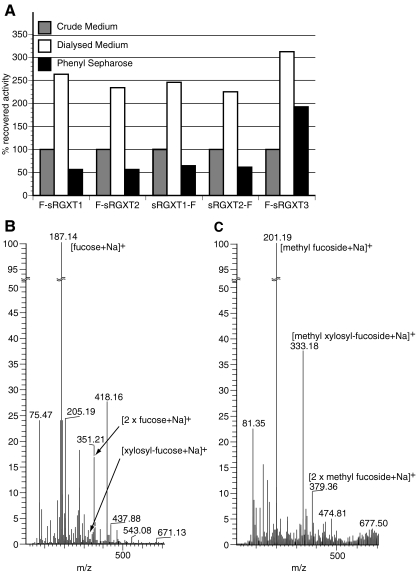

The high amount of e.g. sucrose and other nutrient compounds in the media fractions often hampers product analyses such as linkage and NMR analysis. We therefore decided to perform crude purifications of the expressed proteins. Two schemes were adopted, one being simple dialysis and the other using a combination of (NH4)2SO4 in concentrations that did not result in precipitation of the GT in question, directly followed by purification on a phenyl Sepharose column and subsequent dialysis. After pre-incubation in 50% saturated (NH4)2SO4, all five proteins, i.e. F-sRGXT1, sRGXT1-F, F-sRGXT2, sRGXT2-F and F-sRGXT3, bound to phenyl Sepharose CL-4 by means of hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 3a). Purification of crude media on phenyl Sepharose resulted in a 2-3 fold concentration of activity and 56–61% recovery for F-sRGXT1, sRGXT1-F, F-sRGXT2 and sRGXT2-F while 190% apparent yield and 8-fold concentration was achieved for F-sRGXT3. Recoveries above 100% probably result from interfering constituents of the spent Pichia medium since simple dialysis of the crude media resulted in a 2 to 3 fold increase in total activities for all enzymes. The soluble parts of RGXT1, RGXT2 and RGXT3 have three, four and seven predicted N-glycosylation sites, respectively. F-sRGXT3 was produced as an extremely hyperglycosylated protein in P. pastoris, as judged from the high MW smears on immunoblots [20]. The hyperglycosylation probably accounts for the chromatographic properties of F-sRGXT3 on phenyl Sepharose from which it is more readily eluted.

Fig. 3.

Concentration of activity and ESI-MS analysis. a. Concentration of activity of RGXT1, RGXT2 & RGXT3 by applying i) simple dialysis of the media fractions or ii) liquid chromatography on a Phenyl Sepharose CL4 column (binding of enzyme in 50% saturated (NH4)2SO4 to phenyl Sepharose columns followed by elution of bound protein and dialysis of eluate). Total activities are given relative to the total activity in one volume of crude media (100%), i.e. the phenyl Sepharose concentrated activities have to be multiplied with a factor of 4 for direct comparison on a μl to μl basis. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) of xylosyltransferase assays containing dialysed F-sRGXT2 and 0.5 M L-fucose as acceptor b and dialysed sRGXT1-F and 0.005 M Me α-L-fucoside as acceptor c. The methyl α-D-xylosyl-α-L-fucoside disaccharide product of m/z 333 ([M+Na]+), the α-D-xylosyl-α-L-fucose disaccharide product of m/z 319 ([M+Na]+) and sodium acceptor adducts are indicated on the chromatograms

The authenticity of the formed disaccharide product was verified using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). However, substantiation of disaccharide product formed in xylosyltransferase assays containing the standard amounts of free sugar (0.5 M L-fucose) by ESI-MS was only feasible when the enzymes had either been subjected to simple dialysis or purification on a phenyl Sepharose column (Fig. 3b). Replacing L-fucose with the better acceptor substrate methyl α-L-fucoside [19], enabled lowering the acceptor-concentration 10 or 100 fold in the assay, thus improving the signal to noise ratio significantly (Fig. 3c).

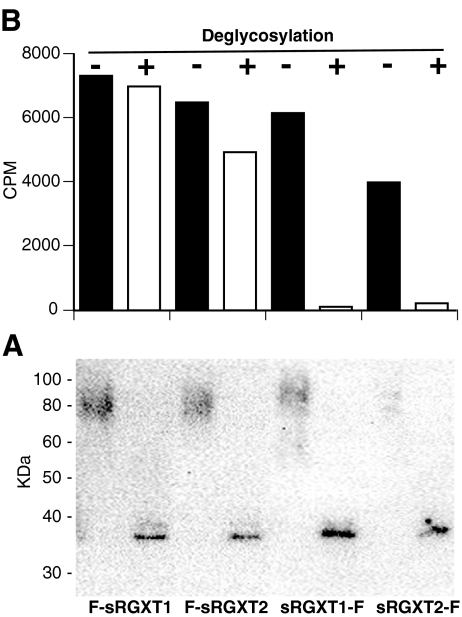

Deglycosylation of hyper-glycosylated proteins

Placement of the Flag-tag in either the N- or C-terminus did not appear to influence the glycosylation pattern of soluble versions of RGXT1 and RGXT2. In order to investigate whether the apparent hyper-glycosylation affected the intrinsic enzymatic activities, enzyme mediated deglycosylation of the two versions of RGXT1 and of RGXT2 was attempted. The four enzymes were incubated with Peptide:N-glycanase and O-glycanase and subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting and xylosyltransferase assays. Deglycosylation of the four proteins was successful at both 25°C and 37°C resulting in shifts from high molecular smears to single, well defined bands at sizes corresponding to the predicted MWs, suggesting complete deglycosylation of the proteins had taken place (Fig. 4). Deglycosylation resulted in almost complete loss of xylosyltransferase activity of the C-terminally tagged proteins whereas activity of the N-terminally tagged proteins was not affected. Thus, de-glycosylation did not, in any case, increase the inherent activity of the enzymes.

Fig. 4.

Deglycosylation of F-sRGXT1, sRGXT1-F, F-sRGXT2 and sRGXT2-F. Immunoblotting analysis of N- and O-glycanase treatments of F-sRGXT1 (Lane 2), F-sRGXT2 (Lane 4), sRGXT1-F (Lane 6) and sRGXT2-F (Lane 8) and the untreated controls F-sRGXT1 (Lane 1), sRGXT2-F (lane 3), sRGXT1-F (Lane 5) and sRGXT2-F (Lane 7). Activities of the corresponding xylosyltransferase assays using 0.5 M L-fucose as acceptor substrate (activities are given directly as counts per minute (CPM)) are depicted beneath. Only data set for the 25°C incubations are shown

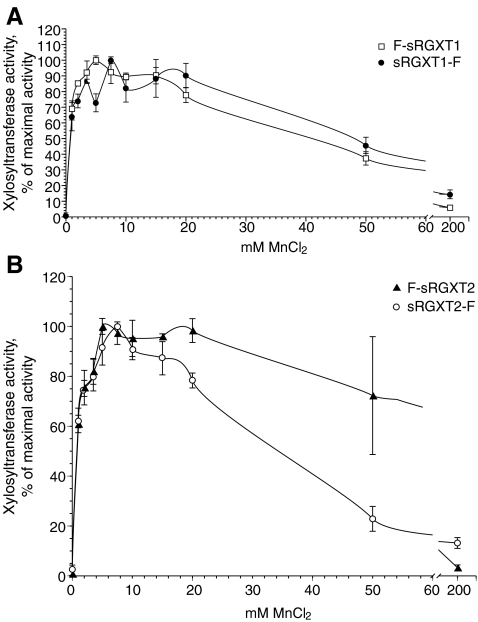

Divalent cations are required for enzymatic activity

RGXT1, RGXT2 and RGXT3 are classified into CAZY GT family 77, and hence predicted to have a retaining mechanism of transfer and to adopt the GT-A fold. GTs adopting the GT-A fold have been reported to require a bound cation (Mn2+ or Mg2+) for catalysis [29]. Most of the GTs adopting the GT-A fold contain the so-called DxD motif (often seen as DxD or DD [30]) that is implicated in binding of the nucleotide sugar [29]. In an earlier bioinformatics study, we identified the DxD motif in silico in all three proteins [27]. In the present study the predicted absolute requirement of a divalent cation, in this case Mn2+, is demonstrated for the RGXT1 and RGXT2 enzymes (Fig. 5). The RGXT1 and RGXT2 enzymes displayed optimum between 5 and 7.5 mM Mn2+ and retained more than 70% of the maximal activity in the range between 2 to 20 mM Mn2+. Substitution of MnCl2 with MgCl2 resulted in a more than 3 fold reduction in activity (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Mn2+ dependence. F-sRGXT1 & sRGXT1-F (A) and F-sRGXT2 & sRGXT2-F b were expressed for 96 h at 20°C, and the media fraction dialyzed as described in the Material and Methods section. 5 μl of dialyzed media fractions were incubated in standard xylosyltransferase assays containing 0.5 M L-fucose and the depicted Mn2+ concentrations (as MnCl2), which were incubated at 30°C for 1 h. Values represent means ± SD (n = 3)

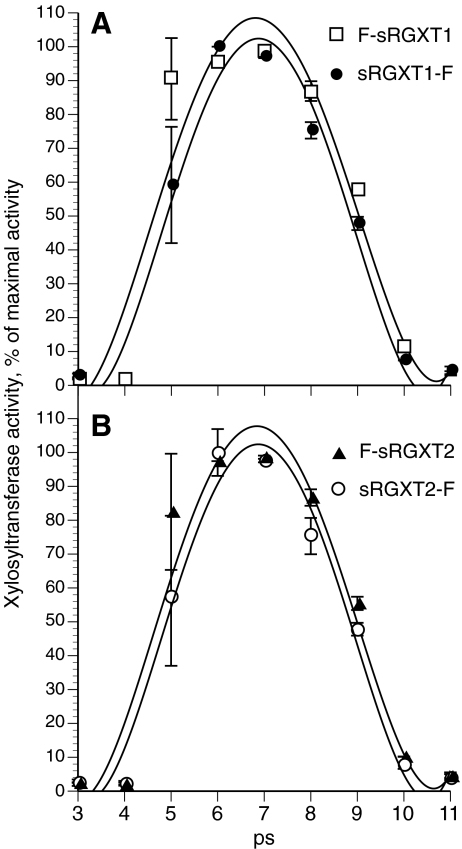

The four xylosyltransferase variants are active over a broad pH spectrum

The four enzymes displayed mono-phasic pH dependent curvatures when assayed in 25 mM ammonium formate in a pH range between pH 3 and pH 11 (Fig. 6). The enzymes retained between 50–60% of their optimal activities between pH 5 and pH 9, with the highest activity around pH 7.

Fig. 6.

pH dependence. F-sRGXT1 & sRGXT1-F a and F-sRGXT2 & sRGXT2-F b were expressed for 96 h at 20°C, and the media fraction dialyzed as described in the Material and Methods section. 5 μl of dialyzed media fractions were incubated in standard XylT assays at the depicted pHs, which were incubated at 30°C for 1 h. Values represent means ± SD (n = 2)

Comparison of RGXT1 and RGXT2 expressed in insect cells versus in P. pastoris

Based upon semi-quantitative western analysis and coomassie stained SDS-page gels with T7-tagged reference protein, T7-tagged RGXT1 and RGXT2 were estimated to be expressed in baculovirus transfected insect sf9 cells at levels within the range of 5–9 mg protein • L-1 medium (data not shown). On a unit to unit basis (1 U = 1 nmol substrate conversion • min-1 • μl medium-1), the four proteins expressed in P. pastoris and dialysed yielded similar activities (within the range 0.011 to 0.013 U) to RGXT1 and RGXT2 expressed in baculovirus transfected insect sf9 cells.

Dialysis of sf9 derived media fractions containing expressed RGXT1 and RGXT2 resulted in slightly reduced activities.

Discussion

More than 200 type II GTs are believed to participate in the synthesis of the unique and complex plant CW, and although heterologous expression is a key element in the assignment of function, successful heterologous expression and demonstration of enzymatic activity of plant CW GTs are rare events (Cf. e.g. recent 11th Cell Wall Meeting, Physiol Plant. 130). One prerequisite for advancing this field is identification and development of suitable expression hosts and schemes. In the present study, we investigated P. pastoris as host system for expression of two retaining plant CW xylosyltransferases, RGXT1 and RGXT2, and using this host system we have made a first basic characterization of the enzymes and provide a simple straightforward framework for how expression and elucidation of enzymatic activity may be addressed in the attempt to assign function to a given GT.

By introducing subtle modifications in the commercially available vector pPiczαA, constructs enabling expression of secreted N- and C-terminal Flag-tagged fusion-proteins were prepared. In the course of a 5 day induction period at 20°C, both N- and C-terminal Flag-tagged RGXT1 and RGXT2 were shown to accumulate in ample amounts with somewhat constant catalytic turnover numbers in the range of 0.15 to 0.3 • sec-1, thus suggesting that the enzymes were relatively stable in the media fractions under the conditions used for expression. The relatively low turnover rates may result from sub-optimal assay conditions of the free sugar assay and inhibitory substances in untreated media fractions. While enzymatic activity of the four RGXT1 and RGXT2 variants was found to increase 2-3 fold upon simple dialysis of the media, phenyl Sepharose mediated purification of F-sRGXT3 resulted in a ca. 8 fold increase in activity when compared on a μl to μl basis. Importantly, these simple extra rough purification steps may determine whether margin activities in sub-optimal general assays, such as the free-sugar assay, are detected. Simple dialysis and phenyl sepharose mediated purification of the media fractions were also found to enable direct verification of the product formed in crude assay mixtures using ESI-MS, thus adding a confirmatory layer to the free sugar assay.

For many mammalian GTs a native C-terminus has been shown to be absolutely required for activity [31–33], a requirement that was confirmed for the Golgi localized β-1,2-XylT from A. thaliana, which is involved in protein N-glycosylation [34]. Here we demonstrate that addition of the apparent non-disruptive Flag-tag to the C-terminus, possessing the catalytic domain, of the soluble part of RGXT1 and RGXT2 does not appear to influence enzyme activity.

The migration patterns of RGXT1, RGXT2 and RGXT3 on denaturing SDS-PAGE gels, suggest that the enzymes are hyper-glycosylated, and that the predicted number of N-glycosylation sites in the proteins correlate with the degree of glycosylation. In order to investigate whether the enzymatic activity might be hampered by the hyper-glycosylation, the enzymes were subjected to enzyme mediated deglycosylation. Loss of activity following deglycosylation of Pichia-expressed enzymes is not unusual (see e.g. [35]). The enzymatic activity after deglycosylation was almost retained for N-terminal tagged RGXT1 and RGXT2, however, demonstrating that activity can be retained and that glycosylation of the two enzymes is not needed for activity in vitro.

Previously, the A. thaliana RGXT1 and RGXT2 were predicted to adopt the GT-A fold [27]. The dependence of Mn2+ or, less efficiently, Mg2+ is common for GTs especially of the GT-A (SpsA) superfamily [29, 36]. The absolute requirement of Mn2+ with a somewhat broad optimum in the range between 2 and 20 mM was demonstrated for all of the enzymes tested, thus in magnitudes exceeding the concentration of Mn2+ in the Golgi vesicles, which is expected to be in the sub millimolar range. A similar range was observed for another member of the GT77-family, the Dictyostelium cytosolic UDP-Galactose:Fucoside α-1,3-Galactosyltransferase [37].

Expression of RGXT1 and RGXT2 in P. pastoris and in another commonly used system the baculovirus sf9 cells, yielded similar activities with estimated turnover numbers within the same range thus also in this respect making P. pastoris along with the overall expression and initial characterisation scheme presented here, a strong competitive host candidate for expression of plant GTs.

Acknowledgement

Dorthe Christiansen, Annette Hansen and Hanne Hansen are thanked for skilful technical assistance. This work was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (Peter Ulvskov, Bent Larsen Petersen, Henrik Vibe Scheller), The Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (I.D. Grant No. 23-04-0238), the Carlsberg Foundation (Jack Egelund) and by contract MRTN-CT-2004-512265 'Wallnet' of the European Union FP6 Program (Kirsten Faber).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- CAZy

Carbohydrate Active EnZyme

- CW

cell wall

- Csl

Cellulose synthase-like

- CPM

counts per minute

- His

histidine

- GT

glycosyltransferase

- ESI-MS

electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- F-sRGXT1/2/3

N-terminally Flag-tagged soluble Rhamnogalacturonan Xylosyltransferase 1, or 2 or 3

- RG-II

rhamnogalacturonan II

- sRGXT1/2-F

Rhamnogalacturonan Xylosyltransferase 1 or 2 soluble with a C-terminal Flag-Tag

- TMD

trans membrane spanning domain

- XylT

xylosyltransferase

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation and The Danish Research Agency

References

- 1.Coutinho, P.M., Henrissat, B.: Carbohydrate-active enzymes server at URL: http://afmb.cnrs-mrs.fr/ ~cazy/CAZY/index.html (1999)

- 2.Coutinho PM, Deleury E, Davies GJ, Henrissat B. An evolving hierarchical family classification for glycosyltransferases. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;328:307–317. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coutinho PM, Stam M, Blanc E, Henrissat B. Why are there so many carbohydrate- active enzyme-related genes in plants? Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:563–565. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheible W-R, Pauly M. Glycosyltransferases and cell wall biosynthesis: novel players and insights. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2004;7:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerouxel O, Cavalier DM, Liepman AH, Keegstra K. Biosynthesis of plant cell wall polysaccharides: a complex process. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006;9:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheller HV, Jensen JK, Sørensen SO, Harholt J, Geshi N. Biosynthesis of Pectin. Physiol. Plant. 2007;129:283–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2006.00834.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohnen D. Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008;11(3):266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhugga KS, Barreiro R, Whitten B, Stecca K, Hazebroek J, Randhawa GS, Dolan M, Kinney AJ, Tomes D, Nichols S, Anderson P. Guar seed beta-mannan synthase is a member of the cellulose synthase super gene family. Science. 2004;303:363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1090908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liepman AH, Wilkerson CG, Keegstra K. Expression of cellulose synthase-like (Cls) genes in insect cells members encode mannan synthases reveals that ClsA family members encode mannan synthases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2221–2226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409179102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocuron JC, Lerouxel O, Drakakaki G, Alonso AP, Liepman AH, Keegstra K, Raikhel N, Wilkerson CG. A gene from the cellulose synthase-like C family encodes a beta-1, 4 glucan synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8550–8555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703133104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton RA, Wilson SM, Hrmova M, Harvey AJ, Shirley NJ, Medhurst A, Stone BA, Newbigin EJ, Bacic A, Fincher GB. Cellulose Synthase–Like CslF Genes Mediate the Synthesis of Cell Wall (1, 3;1, 4)-β-D-Glucans. Science. 2006;311:1940–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.1122975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perrin RM, DeRocher AE, Bar-Peled M, Zeng W, Norambuena L, Orellana A, Raikhel NV Keegstra K. Xyloglucan fucosyltransferase, an enzyme involved in plant cell wall biosynthesis. Science. 1999;284:1976–1979. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5422.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanzin GF, Madson M, Carpita NC, Raikhel NV, Keegstra K, Reiter W-D. The mur2 mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana lacks fucosylated xyloglucan because of a lesion in fucosyltransferase AtFUT1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3340–3345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052450699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards ME, Dickson CA, Chengappa S, Christopher C, Michael J, Gidley MJ, Grant Reid SJ. Molecular characterisation of a membrane-bound galactosyltransferase of plant cell wall matrix polysaccharide biosynthesis. Plant J. 1999;19:691–697. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faik A, Price NC, Raikhel NV, Keegstra K. An Arabidopsis gene encoding an α–xylosyltransferase involved in xyloglucan biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102644799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavalier DM, Keegstra K. Two Xyloglucan Xylosyltransferases Catalyze the Addition of Multiple Xylosyl Residues to Cellohexaose. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:34197–34207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madson M, Dunand C, Li X, Verma R, Vanzin GF, Caplan J, Shoue DA, Carpita NC, Reiter W-D. The MUR3 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a xyloglucan galactosyltransferase theat is evolutionarily related to animal exotosins. Plant Cell. 2003;15:662–1670. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sterling JD, Atmodjo MA, Inwood SE, Kolli VSK, Quigley HF, Hahn MG, Mohnen D. Functional identification of an Arabidopsis pectin biosynthetic homogalacturonan galacturonosyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:5236–5241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600120103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egelund J, Petersen BL, Motawia JS, Damager I, Faik A, Clausen H, Olsen CE, Ishii T, Ulvskov P, Geshi N. Arabidopsis thaliana RGXT1 and RGXT2 Encode Golgi-Localized (1, 3)-a-D-Xylosyltransferases Involved in the Synthesis of Pectic Rhamnogalacturonan-II. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2593–2607. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egelund J, Damager I, Faber K, Olsen CE, Ulvskov P, Petersen BL. Functional characterisation of a putative RhamnoGalacturonan II specific XylosylTransferase. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3217–3222. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen JK, Sørensen SO, Harholt J, Geshi N, Sakuragi Y, Møller I, Zandleven J, Bernal AJ, Jensen NB, Sørensen C, Pauly M, Beldman G, Willats WGT, Scheller HV. Identification of a Xylogalacturonan Xylosyltransferase Involved in Pectin Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1289–1302. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voinnet O, Rivas S, Mestre P, Baulcombe D. An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant J. 2003;33:949–956. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowles D, Lim E-K, Poppenberger B, Vaistij FE. Glycosyltransferases of Lipophilic Small Molecules. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006;57:567–597. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilgen, C., Lin-Cereghino, J.: Cregg, J.M.: Pichia pastoris. In: Production of Recombinant Proteins: Novel Microbial and Eukaryotic Expression Systems (Gellissen G, ed), pp. 143-162. Wiley-VCH (2004)

- 25.Rachel DR, Hearn MTW. Expression of heterologous proteins in Pichia pastoris: a useful experimental tool in protein engineering and production. J. Mol. Recognit. 2005;18:119–138. doi: 10.1002/jmr.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Cereghino GP, Lin Cereghino J, Ilgen C, Cregg JM. Production of recombinant proteins in fermenter cultures of the yeast Pichia pastoris. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002;13:329–332. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(02)00330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egelund J, Skjodt M, Geshi N, Ulvskov P, Petersen BL. A complementary bioinformatic approach to identify potential plant cell wall glycosyltransferase encoding genes. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:2609–2620. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.042978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brückner K, Perez L, Clausen H, Cohen S. Glycosyltransferase activity of Fringe modulates Notch-Delta interactions. Nature. 2000;406:411–415. doi: 10.1038/35019075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breton C, Snajdrova L, Jeanneau C, Koca J, Imberty A. Structures and mechanism of glycosyltransferases. Glycobiol. 2006;16:29–37. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charnock SJ, Henrissat B, Davies GJ. Three-dimensional structures of UDP-sugar glycosyltransferases illuminate the biosynthesis of plant polysaccharides. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:527–531. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Z, Vo L, Macher BA. Structure–function analysis of human alpha1, 3-fucosyltransferase. Amino acids involved in acceptor substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;71:8818–8823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korczak B, Le T, Elowe D, Datti A, Dennis JW. Minimal catalytic domain of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V. Glycobiol. 2000;10:595–599. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.6.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Vries T, Storm J, Rotteveel F, Verdonk G, van Duin M, Van den Eijnden DH, Joziasse DH, Bunschoten H. Production of soluble human a3-fucosyltransferase (FucT VII) by membrane targeting and in vivo proteolysis. Glycobiol. 2001;11:711–717. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.9.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagny S, Bouissonnie F, Sarkar M, Follet-Gueye ML, Driouich A, Schachter H, Fayel L, Gomord V. Structural requirements for Arabidopsis β1,2-xylosyltransferase activity and targeting to the Golgi. Plant J. 2003;33:189–203. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7412.2002.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mølhøj M, Ulvskov P, Dal Degan F. Characterization of a functional soluble form of a Brassica napus membrane-anchored endo-1,4-β-D-glucanase heterologously expressed in Pichia pastoris. Plant Physiol. 2001;127(2):674–684. doi: 10.1104/pp.010269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West CM. Evolutionary and functional implications of the complex glycosylation of Skp1, a cytoplasmic/nuclear glycoprotein associated with polyubiquitination. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003;60:229–240. doi: 10.1007/s000180300018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ketcham C, Wang F, Fisher SZ, Ercan A, van der Wel H, Locke RD, Sirajud-Doulah K, Matta KL, West CM. Specificity of a Soluble UDP-Galactose:Fucoside 1, 3-Galactosyltransferase That Modifies the Cytoplasmic Glycoprotein Skp1 in Dictyostelium. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:29050–29059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]