Forces are aligning to shift American health care into the Information Age: an age which financial institutions, airlines, supermarkets and most manufacturing industries have already entered. The shift, which these institutions have already experienced, will facilitate the establishment and widespread use of standardized databases in health care. The databases are known by the terms electronic medical records (EMRs), electronic health record (EHRs) or personal health records (PHRs).

These forces underlie today's shift towards full use of a universally accepted electronic medical record, electronic health record and for a personal health record:

An unprecedented revolution in computer and communication technologies

The widespread availability of affordable electronic tools

Burgeoning interest among patients in having access to their own medical information

Rapid progress in understanding the human genome and proteosome

The rising cost of health care

The increasing administrative burden upon physicians

A perception that medical errors are increasing

Demands for widely comparable measures of quality care

The need for post-marketing surveys of new drugs

Our increasingly mobile society

Greater emphasis upon evidence-based medicine

Reimbursement incentives that pay for using EHRs and for providing quality care

Reduced malpractice premiums for physicians that fully employ these technologies.

What is an Electronic Health Record?

An EMR contains the results of clinical and administrative encounters between a provider (physician, nurse, telephone triage nurse, and others) and a patient that occur during episodes of patient care. Consequently, the EMR reflects the practice style, job function, knowledge and skill of the providers who create it. It necessarily includes data structures and data elements that reflect those providers' systems. In an attempt to bring some structure to this emerging field, in 1991 the Institute of Medicine defined the basic functions of an EMR, then known as the computer-based patient record (CPR). The Institute of Medicine's definition remains the gold standard (see Table 1 on page 58).

To supplement the provider-generated information in the EMR, the personal health record (PHR) is a medical record maintained by the patient. The PHR includes electronic copies of information patients have received from their providers.

Finally, the concept of the EHR was formulated to integrate an individual's multiple, physician-generated, electronic medical records and the patient-generated personal health record. Intended to be comprehensive, the EHR should facilitate optimal management of the health of an individual or, when used in aggregate, of a population. EHRs should allow sharing of information about patients between any authorized providers. A patient should be able to enter any health care setting, provide authorization, and then consult with a provider who has ready access to his complete health record. EHRs should be securely linked over the Internet and should be integrated seamlessly with medical information for the education of both providers and patients. Table 2 lists common functions of an EHR divided by practice, clinical, system, and chemotherapy/drug management components. Table 2 lists some common medical and oncology-specific data elements (data fields) for an electronic health record.

Why Adopt an Electronic Health Record?

The overriding reason for us to use these technologies is to have all of the information we need for patient care, for education, and for practice management readily accessible at the point-of-care. It should not matter whether the computer terminal is in our office, at our clinic workstation, in the examination room, at home, or at the hospital bedside. Oncologists need support for their clinical decisions that is patient-specific, as well as timely reminders. Electronic links across care settings should facilitate collaborative, coordinated approaches among caregivers and enhance the tracking and monitoring of the quality of our care activities.

Other important reasons to use EHRs include reduction of medical errors, reduction of lost or redundant paperwork and support for reimbursement for our work. EHRs can also help the oncology community contribute fully to the development of an efficient national health care system that is based upon evidence-based medicine and responsive to the needs of all constituents. If the National Health Information Infrastructure is activated, EHR implementation should allow us and our patients to participate.

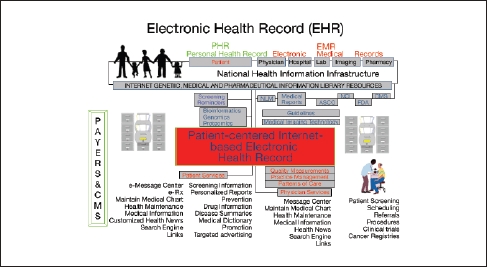

The evolving EHR will include many components linking patients, practices, clinics, imaging centers, hospitals, health plans, laboratories and pharmacies over the Internet in a confidential, secure and standardized format. We will use the Internet for practice management; scheduling, visits, procedures, and laboratory tests; documentation; referrals; prescriptions; patient eligibility; decision support; analyzing patterns of care; error checking; and e-mail communication (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed oncology EHR and the National Health Information Infrastructure (NHII)

Just as we use the Internet constantly, so do our patients. Oncologists must begin to guide patients towards credible sources of online medical information posted on the Internet and to routinely document this guidance. These changes go hand in hand with the increasing role of information science in both medicine itself and in public policy decisions regarding medicine, where today's emphasis falls strongly on the improvement of the quality and the coordination of patient care.

Computers today are inexpensive and easy to use. Most physicians today are willing to work in ways that those physicians once resisted, using computer support systems to make decisions and adopting standardized forms of data elements. Most physicians are comfortable using clinical guidelines, working with quality measures, and benchmarking both their practices and their compliance with HIPAA regulations. Clinical oncology, with its emphasis on clinical trials and on the gathering of longitudinal data on patients represents a natural arena for EHRs.

Paying For and Supporting EHR Acquisition

Government and other third-party payers, our patients and other constituents of the health care system now acknowledge that doctors and hospitals alone cannot underwrite the cost of adopting health care information technology since physicians are unlikely to reap most of the financial benefits resulting from technology use. This recognition is a major justification for providing physicians and hospitals with financial incentives to adopt EHRs.

Government and various concerned private parties have begun to address problems holding back widespread adoption of electronic records. Payers have begun to reimburse for electronic communication between patients and their doctors and the public has started to take advantage of this opportunity. Agreements are beginning to be reached regarding needed standards that permit the exchange of data in ways that ensure its security, authenticity and interoperability. Oncologists must ratchet up the level of their participation in the now ongoing process of defining of those tools, functions and datasets that will become components of EHRs.

Government representatives and payers, in an effort to improve the efficiency of our health care system, are also studying treatment patterns and ways to both define and measure the quality of care. They are contemplating offering rewards to physicians who can demonstrate quality improvement, improvement in the experiences that their patients report, and cost-effectiveness of the treatment approaches that they choose.

More Practical Advantages of EHRs

Oncologists today face heavy new administrative loads. Our offices process excessive paper. We face significant delays in obtaining charts and reports that we need. We face huge transcription costs and urgent requirements to protect all the medical information that we collect. In coming years, these challenges will intensify. We will be responsible for more accurate measurements and proofs that we provide quality care. We will have to integrate computer and communication technologies, wireless technologies and personal digital assistants (PDAs) into our daily activities.

We will also have to do better in the battle for fair reimbursement. Concurrently, our oncology practices will also face imperatives that we more strongly adhere to evidence-based medical practices. We will face this staggering array of pressures at the same time that our practices, which generally exist in small groups, are becoming more fragmented and cash starved.

Data that is collected in oncology offices is still mostly recorded on paper. The quantity of this data is staggering. Unlike most digitally recorded data (such as that available on the Internet) our paper-based data cannot be easily searched or analyzed. Using EHRs, physicians can quickly locate information on a given patient's problems, medications and test results. Thus, EHRs can enhance the decision-making process and the communication of decisions via electronic means to others involved. EHRs can confer financial benefits to physicians through reduced costs for transcription and medical record staff. Furthermore, EHRs can improve coding accuracy that enhances patient safety, increases the quality of care and improves the capture of charges. With these efficiencies, EHRs can allow physicians to see patients at a reduced pace. Chart maintenance can be streamlined and documentation for payers assured. Patients can enjoy a higher quality of care when they receive prescriptions, instructions for care and needed summaries of their medical history electronically. Table 3 summarizes some of the potential benefits for oncology practices provided by an EHR.

Table 3.

Benefits of EMRs for Oncology Practices

| EHRs can help oncologists perform many tasks more effectively: |

| Patient care: Enter physician orders • Make use of computerized support systems for decision-making • Prevent drug interactions and improve compliance • Provide our patients with access to their health records, disease management tools and health information resources • Reduce errors of omission and commission through the provision of reminders and alerts • Use clinical guidelines in a timely fashion • Use examples of best practices |

| Research and analysis: • Analyze patterns of cancer care given • Document both our clinical rationale and the service lines that we have provided • Measure and benchmark the quality of care provided • Manage and understand the clinical information we collect • Facilitate data collection for clinical trials • Provide a variety of ways to view the same data (such as in free text, database or flow chart formats) • Provide standards-based electronic data storage and reporting (to support efforts in the areas of patient safety and disease surveillance) |

| Financial matters: • Add financial value to “scrubbed” clinical data • Participate in “pay for use” and “pay for quality” initiatives • Employ computerized tools designed to streamline scheduling, claims, and the handling of insurance matters • Ensure secure electronic communication between provider and patient |

| Fulfillment of general informational needs: • Provide access to updated and archived medical information in multiple care settings • Utilize information from the Internet rapidly, whenever needs arise |

EHRs will help oncologists create, maintain, edit, display and manipulate all the data in any individual's record. Aggregates of data will reside in a clinical data repository, an extremely large-scale storage database for EHRs that will facilitate research and clinical trials. Table 4, for example, lists data elements for the management of chemotherapy administration.

Table 4.

Chemotherapy Administration Data Elements

| Patient name | Diluent, amount, mix and time given |

| Name of protocol | Administration route, IV push or infusion |

| Number of protocol | Drug sequence and time |

| Diagnosis | Need for pump, special tubing and filter |

| Patient height | Acute side effects of drugs |

| Patient weight BSA (calculated) |

Number of office visits required to complete therapy |

| Drug procurement source | Central line placement (if needed) |

| Drug authorization obtained if needed | Fatigue 1-4 |

| Pre-treatment tests and results | Nausea & vomiting 1-4 |

| Supportive drugs - pre- & post therapy | Pain 1-4 |

| Chemotherapy drugs - automated dose calculation | Co-signatures for dose calculations Physician signature |

EHRs will facilitate the measurement of many important outcomes for researchers. Oncologists will be able to more readily incorporate clinical guidelines into their daily work by integrating those guidelines into EHRs. Computers will allow the creators of guidelines to obtain virtually instant feedback from intended users of those guidelines regarding their adherence to or departures from the recommendations. This will be valuable in reassessing and revising the guidelines. We will increasingly see collaborative online efforts to bring decision-making support to the oncologist at the point of care. This will foster the growth of evidence-based medicine, reduce medical errors and enforce the documentation of what medical procedures took place and why they were chosen.

The increasing involvement of patients in their own care will be advanced through their ability to access their EHRs online. Patients will be able to maintain copies of their own personal health records, choose physicians, e-mail care providers, make appointments, refill prescriptions and receive prevention and screening reminders. These capabilities will create new roles for oncologists and new responsibilities for patients.

Transition To An EHR May Be Difficult But Is Inevitable

Oncologists already use many software products for practice management. Software already in wide use includes programs designed to handle the following functions: verification of eligibility for insurance; completion of provider forms; provider referrals, patient co-payments; billing; electronic claims; and, in some parts of the country, the filling of prescriptions electronically. Yet fewer than 5% of practicing oncologists use EHRs for reasons that reflect a great many legitimate concerns.

One reason is that standards defining software tools, functions or datasets for electronic records are not yet well-established. Another is that patient data remains highly insecure. Furthermore, physicians worry about how quickly software programs can become obsolete and about the viability of software vendors. They are discouraged by the fact that often one EHR program cannot easily exchange information with another.

Oncologists still face several barriers that they must overcome in order to advance the universal adoption of EHRs (see Table 5). Yet for the first time, our country does have a goal for the universal use of EHRs and a framework for strategic action towards that goal. A consensus exists on the functions to be implemented in an EHR and standards are being established. Investments in health care information technology are increasing and serious studies have addressed the economic factors involved including expected returns on investments in EHRs and reimbursements for the cost of switching to EHRs. Bipartisan support prevails in Congress for enhanced health care information technology, backed by a strong commitment from the President. Concerned players are reaching the needed agreements on the necessary standards, in acknowledgment of the need for EHR applications to easily talk with one another.

Table 5.

Barriers to adoption of the EHR

|

Process Imperfect user interface platform Art of medicine not quantifiable Fragmentation of medical information Fitting into the office workflow Fear of typing Quality of data Parochialism Time Lack of critical mass Difficulty of integration with legacy systems Training and culture Resistance to change |

Technical infrastructure Lack of standards Lack of standardized vocabulary Lack of interoperability Free Text entry vs. structured data Regulatory and privacy uncertainties Security Confidentiality Financing Lack of capital Cost and concerns of ROI Lack of financial incentives Lack of cost benefits perceived by physician Shortage of technical personnel |

We no longer have the luxury of deciding for ourselves about the adoption of health care informatics. Payers, society, and the other major stakeholders have set our task for use. Our challenge now is to use these technologies to the fullest advantage. By doing so, we will most capably address the wide array of challenges that our practices face. Health care informatics can improve ways in which we and our staffs carry out nearly every aspect of our practices, even in the way we connect humanly to our patients. Our success as clinicians and as managers of our practices will depend on our commitment to educate ourselves and to adopt expeditiously.

Readers can find more information on EHRs at:

The American College of Physicians http://www.acponline.org/journals/news/apr04/emrs.htm#resources

The American Medical Informatics Association http://www.amia.org. and its GotEHR at http://www.gotehr.org

The American Academy of Family Practice http://www.aafp.org/fpm

The Healthcare Information and Management System Society http://www.HIMSS.org.

PhysiciansEHR.com http://www.physiciansehr.com

CMS: Prove Quality Measures in Office http://www.doqit.org/doqit/jsp/index.jsp

Markle Foundation/ Connecting for Health http://www.connectingforhealth.org

Foundation for E-health Initiative http://www.ehealthinitiative.org

National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics http://www.NCVHS.hhs.gov

National Health Information Infrastructure http://www.aspe.hhs.gov/sp/nhil

KLAS (EHR comparison site) http://www.healthcomputing.com

DOQ-IT (CMS Quality and EMR Demonstration) http://www.doqit.org

See Report and Recommendations from the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics. A Strategy for Building the National Health Information Infrastructure. Washington DC, November 15, 2001, for a review of the National Health Information Infrastructure

See Stead et al for more information on the essential components of an EHR and the NHII. (Stead WW, Kelly BJ, Kolodner RM. Achievable steps toward building a National Health Information Infrastructure in the United States. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12:113-120.)

For reports criticizing the US health care system for information technological incompetence:

See the President's Information Technology Advisory Council report at http://www.itrd.gov/pubs/pitac/pitac-hc-9feb01.pdf.

Also see reports from the Institute of Medicine:

The IOM/NAS IT Report: To Err is Human at http://www.nap.edu/openbook/0309068371/html/

Ensuring Quality Cancer Care at http://books.nap.edu/catalog/6467.html

Using Data Systems to Assure Quality Cancer Care at http://books.nap.edu/catalog/9970.html

Crossing the Quality Chasm at http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10027.html

Table 1.

EHR functions

| Practice Management | |

| Automated charge entry from EHR Benchmark practices: quality and cost-effectiveness Clinical EHR and financial system integration Coding: ICD-9, CPT, J-codes Communication management: E-mail,Telephone/Fax Contacts management Cost-effectiveness analyses Differential diagnostic software integration Disease surveillance Disease/symptom-based templates and automated pick lists Document quality measures in office Documentation office visits (CMS E/M guidelines) Electronic billing & insurance Electronic claims Electronic consults Financial analysis of practice Guideline, disease management and algorithm integration Health services research Hospital admission and discharge management Image filing Insurance eligibility verifications |

Lab orders, online Outcomes measurement Patient co-payments Patient demographics Patient education/handouts/Internet sites Patient satisfaction measurement Patterns of care Practice population analysis Practice Web portal Provider forms completion Provider Information Quality Assurance Quality of life measurement Referral ordering/tracking Results reporting Scheduling chemotherapy administration Scrubbed clinical and demographic data capabilities Security (audits, pw, user access hierarchy) Software interfaces with practice management, lab,imaging, hospital, payer and pharmacy systems Statistics package Timeliness of care measurement |

| Clinical Management | |

| Cancer diagnosis Chemotherapy history Chief complaints Clinical guidelines Clinical pathways Clinically structured messages, customized Demographic information Document clinical rationale and service lines provided E-Mail with patients End of life tools: Health care proxies, living wills, power of attorney Flow charts Follow up Functional status Health maintenance History present illness Immunizations Immunotherapy history Internet library and searching services Medical calculators Nomograms Online textbooks and compendia integration Operative reports |

Past medical history Pathology: H & E, IHC, chromosomal abnormalities, gene expression, proteomics Patient handouts Personal Health Record Personal history Physical examination Problem lists active/inactive Progress notes Radiation oncology history Recurrence Reminders and alerts Response and survival parameters Review of Systems Staging tools: TNM Surgical history Survival analyses Symptom management: physical, psychological, spiritual and social Template-based tools for Encounters and Visits (macros and expanded text) Treatment plans and instruction Toxicity and adverse reactions management (Common Toxicity Criteria) Tumor measurements Vital signs |

| System Management | |

| Application Specific Program (ASP) aware Appointment scheduler Audio/Video capture Audit trail log Back up: local and remote Cellular connectivity Clinical trials and basic science research tools (CaBIG) aware Controlled clinical vocabulary: SNOMED-CT, UMLS, CaBIG(NCI) Data formats interchangeable: free text, database or flow chart Data mining tools Data warehouse Decision support: drug interactions, allergies, and ddx Dial-In Access Dictation aware Document management/scanning E/M Code and CPT Code analysis and documentation Electronic Data Repository E-mail aware Episodes of care tracking Expandability (Scalability) Fax handling Flow chart (electronic) Granularity (user hierarchy) Graphic, photos and sketch handling Handwriting recognition HIPAA compliant |

HL7 interoperability standards compliant Hospital information system integration Imaging interfaces, commercial Immunization maintenance Internet connectivity Lab interfaces, commercial Multiple cancer diagnoses per patient Multiple views of data: freetext, database, flowsheet Office notes and forms, customizable Operating system neutrality PDA connectivity Personal Health Records for patients Personalized view of data: by user Physician order entry Populate compatible practice management system (mapping, import and export tools) Populate external database repositories: SEER, NCDB, Tumor Registries Referral management Remote log-on Report filer (Labs/Imaging/Procedures/Progress notes/ER visits, Discharge summaries) Report generator (customizable) Track e-mail & phone messages Transcription handling User demographics Utilization management Voice recognition Wireless connectivity |

| Chemotherapy/Drug Management | |

| Allergy checking Alternative medications Chemotherapy balance sheet analyses Chemotherapy coding and reimbursement management Chemotherapy dosage calculator Chemotherapy inventory management Chemotherapy lifetime dose Chemotherapy order sets Chemotherapy regimens management Contraindication checking |

Decision support: drug interactions, allergies, and ddx Drug-Drug interaction checking Electronic pharmacy system interface E-prescription and refill maintenance Flow Charts J codes compliant Medication lists, current and historical Pain management tools Payer formulary management |

Table 2.

Data elements for personal, provider, and oncology health records

| Personal Health Data Elements | Provider Data Elements | Oncology Data Elements | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Identification elements | • | • | Historical Date diagnosis Cancer diagnosis Primary site Subsite Laterality Prior Rx Staging primary disease Date staged Geographic site Primary location size Nodes Metastatic sites T | N | M Stage Tumor status Staging metastatic disease Date site(s) Subsite Histology Same as primary in situ Residual Lesion size Volume Status Link with Primary(?) Pathology Date diagnosis Site Gross Morphology Markers Histology Grade Maximum diameter Volume Vascular involvement Lymph involvement Margins Character Size Synchrony DNA ploidy Receptors Histochemistry Genetics Currency Current Rx modalities Status Response Rx intent Rx toleration Rx toxicity Performance status Pain level Fatigue levelSurgery/Procedure Date Procedure |

Purpose Hospital Sentinel nodes Complications Operative findings % Debulked Surgeon Time Procedure Estimated blood loss Transfusion Radiation therapy Purpose Location Dose Start/End date Response Progression date Chemotherapy Regimen (drugs) Purpose Start/End date Ht Wt BSA Response Cycles # Cycle dates Progression date Protocol name Group Protocol # Patient # Immunotherapy Regimen Purpose Start/End date Response # cycles cycle length Progression date Protocol name Group Protocol # Patient # Recurrence rT | rN | rM rStage Date Site(s) Subsite Histology Same as primary in situ Residual Lesion size Volume Status Link with Primary (?) Follow up Last date seen DNR Date of death Autopsy findings |

| Emergency contacts | • | • | ||

| Lifetime health history | • | • | ||

| immunizations, allergies, family history, occupational history, environmental exposures, social history, medical history, treatments, procedures, medicines, outcomes | ||||

| Laboratory results | • | • | ||

| Emergency care information | • | • | ||

| Provider identification and contact information | • | • | ||

| Treatment plans and instructions | • | • | ||

| Health risk factor profile, preventive services and results | • | • | ||

| Health insurance coverage information | • | • | ||

| Correspondence | • | • | ||

| Access and confidentiality information | • | • | ||

| Audit log | • | • | ||

| Self-care trackers: nutrition, activity, medication | • | • | ||

| Health care proxies, living wills, power of attorney | • | • | ||

| Sociodemographic identifiers | • | |||

| gender, birthday, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, living arrangement, educational level, occupation | ||||

| Legal consents or permission | • | |||

| Referral information | • | |||

| Reason for visit | • | |||

| External causes injury/illness | • | |||

| Symptoms | • | |||

| Physical exams | • | |||

| Assessment of patient signs and symptoms | • | |||

| Toxicity assessments | • | |||

| Diagnoses | • | |||

| Orders for lab, radiology and pharmacy | • | |||

| Laboratory results | • | |||

| Radiological images and interpretations | • | |||

| Records of alerts, warnings and reminders | • | |||

| Operative reports | • | |||

| Vital signs | • | |||

| Treatment plans and instructions | • | |||

| Progress Notes | • | |||

| Functional status | • | |||

| Discharge summaries | • | |||

| Outcome analyses | • | |||

| Provider notes | • | |||

| Protocols | • | |||

| Practice guidelines | • | |||

| Clinical decision-support programs | • | |||

| Referral history | • | |||

DNR = do not resuscitate; Ht Wt BSA = height, weight, body-surface area; T | N | M = tumor-node-metastasis Table reproduced from Cancer Medicine, 6th Edition, American Cancer Society and BC Decker, Inc., 2003