Summary

Objectives

Cigarette smoking is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in former Soviet countries. This study examined the personal, familial and psychiatric risk factors for smoking initiation and development of nicotine dependence symptoms in Ukraine.

Study Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Methods

Smoking history and dependence symptoms were ascertained from N=1,711 adults in Ukraine as part of a national mental health survey conducted in 2002. Separate analyses were conducted for men and women.

Results

The prevalence of lifetime regular smoking was 80.5% in men and 18.7% in women, with median ages at initiation among smokers of 17 and 18, respectively. Furthermore, 61.2% of men and 11.9% of women were current smokers; among the subgroup of lifetime smokers, 75.9% of men and 63.1% of women currently smoked. The youngest female cohort (born 1965–1984) was 26 times more likely to start smoking than the oldest. Smoking initiation was also linked to childhood externalizing behaviors and antecedent use of alcohol in both genders, as well as marital status and personal alcohol abuse in men, and childhood urbanicity and birth cohort in women. Dependence symptoms developed in 61.7% of male and 47.1% of female smokers. The rate increased sharply in the first four years after smoking initiation. Dependence symptoms were related to birth cohort and alcohol abuse in both genders, as well as growing up in a suburb or town and childhood externalizing behaviors in men, and parental antisocial behavior in women.

Conclusions

Increased smoking in young women heralds a rising epidemic in Ukraine and underscores the need for primary prevention programs, especially in urban areas. Our findings support the importance of childhood and alcohol-related risk factors, especially in women, while pre-existing depression and anxiety disorders were only weakly associated with starting to smoke or developing dependence symptoms.

Keywords: Ukraine, Soviet, smoking, nicotine dependence, risk factors, alcohol

Introduction

In Eastern Europe, legislation was enacted in the last decade limiting the advertisement, sale, and consumption of tobacco in an effort to curb the morbidity and mortality associated with cigarette smoking.[1] Nevertheless, a substantial percentage of adults, particularly men, smoke despite knowledge of its adverse consequences.[2][3][4] In Ukraine, the second largest country in the former Soviet Union, smoking has reached epidemic proportions.[2] Moreover, in Ukrainian men, 28% of all deaths and 50% of cancer deaths are attributable to smoking, and a 35-year old man has a 1 in 4 chance of dying from tobacco-associated causes before age 70.[5] Despite its public health consequences, smoking cessation programs are virtually non-existent in Ukraine.

In the last decade, population-based surveys of smoking were undertaken in 11 former Soviet countries.[2][3][4][6][7][8][9][10] The median rates of current smoking were 56.0% in men and 9.3% in women. The most consistently reported correlates were middle-age (30–49 years), poor socioeconomic conditions, and low education in men, and younger age and urbanicity in women.[2][3][6][7][9][10] The median rates of nicotine dependence (defined as more than 20 cigarettes per day and smoked within an hour of waking) were 17% in men and 7% in women.[6] Gender was consistently related to nicotine dependence.[6][8]

Outside the former Soviet Union, several studies have focused on the determinants of smoking initiation and development of dependence symptoms. These studies provide data that are informative for designing and targeting prevention strategies. While many such studies were prospective, cross-sectional cohort studies with careful dating of age of onset were also conducted.[11] Smoking initiation was consistently predicted by age,[11][12][13] religiosity,[14] alcohol behaviors,[15][16] and childhood externalizing behavior.[13][17][18] Mood and anxiety disorders,[15] parental depression,[19] parental substance abuse,[20] poor relationship with parents (especially for females)[18][21] and childhood abuse[22] were significant in several studies. The findings for gender, urban residence and low parent education were inconsistent.[18][23][24] The few studies examining the transition to dependence found strong associations with pre-existing psychiatric and substance disorders.[15][20][25]

The present report extends this body of research by examining the onset of regular smoking, the transition to dependence symptoms, and the contributions of pre-existing personal, familial and psychiatric risk factors in a nationally representative sample of Ukraine.[26][27] This study represents an initial attempt to address these issues in a former Soviet country.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

The data come from the Ukraine World Mental Health survey (Ukraine-WMH), a nationally representative study ages 18 and older from the 24 oblasts (states) and the republic of Crimea.[26][28] The sampling followed a four-tier multi-stage cluster design described in detail elsewhere.[26] Face-to-face interviews were administered by professional interviewers from the Kiev International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) in collaboration with the Ukrainian Psychiatric Association (UPA) from February–December, 2002. The response rate was 78.3%. Quality assurance procedures were established for the WMH consortium.[27] The recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the Committees on Research Involving Human Subjects of Stony Brook University and by KIIS and UPA.

After obtaining written consent, all respondents (N=4,725) were administered Part I of the study instrument (see below). Those with DSM-IV mood or anxiety disorders or alcohol dependence plus a probability subsample (16%) of the remainder also received Part II (N=1,720), which included the Tobacco Use module. Complete data on smoking was available for N=1,711.

Measures

The survey instrument was the paper-pencil version of the WMH Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI), a structured, modularized interview schedule that elicits DSM-IV psychiatric disorders and included a novel sequence of questions designed to enhance recall of age of onset.[29] Minor refinements were made to the alcohol, trauma, and demographic modules.[26] The Ukraine-CIDI was translated into Russian and Ukrainian following WHO-approved translation procedures.[29]

Smoking

Respondents who “smoked tobacco at least once a week for a period of at least two months” were classified as regular smokers. Nicotine dependence symptoms included (1) physical (increased appetite, decreased heart rate, trouble sleeping) or emotional (irritability, nervousness, difficulty concentrating) withdrawal symptoms; (2) continued use in spite of physical (difficulty breathing, cardiovascular) or emotional (irritability, nervousness, difficulty concentrating) problems; and (3) unsuccessful efforts to quit (at least three attempts). Ages of onset were determined for smoking initiation and for first dependence symptom using age prompts when respondent recall was inexact.[29]

Personal, familial, and psychiatric risk factors

The personal risk factors were: birth cohort (divided into tertiles and corresponding to the periods before 1945, 1945–1964 [end of Stalin through end of Kruschev period], and 1965–1984 [Breshnev-Andropov period]); urbanicity (raised in a city, suburb/town, or rural area); religiosity (religion was important or unimportant while growing up); use of alcohol; marital status; and employment status. The familial risk factors were: father’s education (0–8, 9–10, 11+ years); perceived closeness to parents (close to neither, one, or both); parental antisocial behavior (at least 2 behaviors: arrests, criminal activity, desertion of family, physical fights, child abuse); parental alcoholism (alcohol problems that interfered with life activities during a significant portion of the respondent’s childhood); and parental depression (episodes lasting 2+ weeks that interfered with life activities) or anxiety (episodes of nervousness or anxiety lasting 1+ month or anxiety/panic attacks). The psychiatric risk factors were: childhood externalizing behavior (0, 1, or 2+ behaviors involving inattention, hyperactivity, defiance, or misconduct); DSM-IV alcohol abuse with or without dependence; DSM-IV mood disorder (depression or dysthymia), and DSM-IV anxiety disorder (social phobia, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder).

Data analysis

To account for non-response and selection bias, the data were weighted to approximate the population distribution of Ukraine on key demographic variables.[26] A Part II weight further adjusted for differential selection of Part I respondents. The weighted sample was 45.0% male and the median age was 44.

All analyses were conducted on a person-years database which assigns one observation for each year of a person’s life (78,809 person-years). Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence curves were constructed for age at initiation of regular smoking and years from smoking initiation to first dependence symptom. The log rank test was used to examine gender differences in the resulting curves.

Discrete-time survival analysis was used to study the risk factors for initiation of regular smoking adjusting for the underlying age function and for transition to dependence symptoms adjusting for time since initiation. Logistic regression was applied to the person years file to predict smoking initiation and symptom onset, such that each year was coded ‘0’ for years preceding an event (e.g. started smoking) and ‘1’ for the year the event occurred; subsequent years were censored. Most risk factors were presumed to precede the onset of smoking. However, six were time-varying covariates (ages at first marriage, first job lasting 6 months or more, first use of alcohol, and onset of DSM-IV alcohol abuse, mood disorder, and anxiety disorder). As noted by Breslau,[15] the resulting logistic regression coefficients can be interpreted as survival coefficients, and thus be exponentiated to generate odds ratios.

The analyses were conducted using the SUDAAN software system[30] separately for men and women. In addition, a backwards elimination procedure was used to derive multivariable models, with α=0.05 to sequentially remove non-significant predictors. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 (two-tailed tests).

Results

Smoking initiation

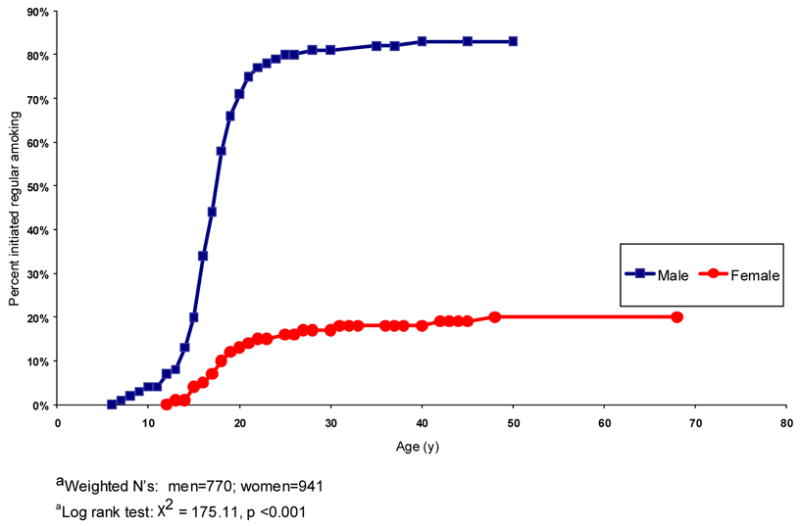

The lifetime prevalence rates of regular smoking were 80.5% in men and 18.7% in women; 61.2% of men and 11.9% of women were current smokers. Among lifetime smokers, 75.9% of men and 63.1% of women were current smokers. In men, initiation accelerated sharply at age 13, remained high through age 19, and leveled off by age 23 (Figure 1). In women, the rate of initiation was highest between ages 14–22, but the initiation slope was less steep than in men. The median age at initiation among all men was 18 and could not be calculated for women due to their low rate of of smoking . In the subgroup of lifetime smokers, the median age at initiation was 17 for men and 18 for women.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of regular smoking in men and womena,b

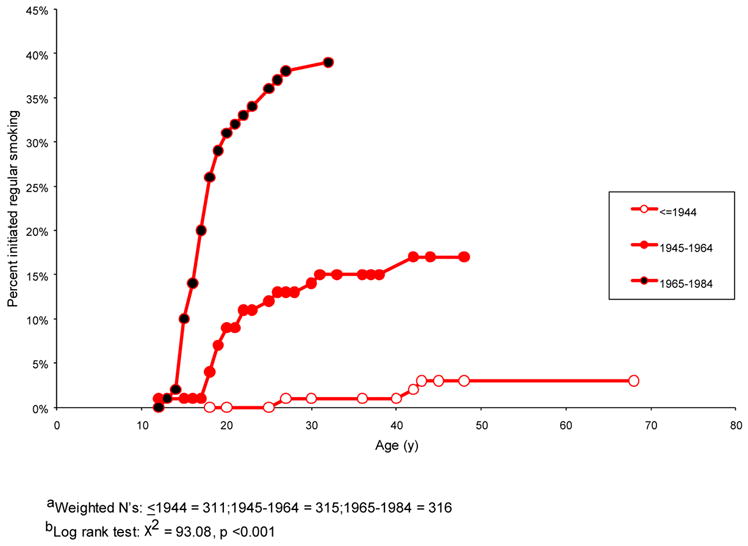

Young men born during the period 1965–1984, raised in a city, already drinking, and not yet married were at increased risk for starting to smoke (Table 1). Greater risk in women was linked to being in the youngest and middle birth cohorts (1945–1964 and 1965–1984), raised in a city or suburb/town, low religiosity, and drinking. Figure 2 illustrates the strong association of birth cohort with smoking initiation in women.

Table 1.

Personal, familial and psychiatric risk factors for smoking initiation: weighted associations

| Males (weighted N=770)

|

Females (weighted N=941)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aORa | 95% CI | P | aORa | 95% CI | P | |

| Personal variables | ||||||

| Birth cohort | ||||||

| <=1944 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1945–1964 | 1.17 | (0.87–1.57) | 0.29 | 7.18 | (3.03–17.02) | < 0.001 |

| 1965–1984 | 1.64 | (1.14–2.36) | < 0.01 | 26.26 | (11.18–61.68) | < 0.001 |

| Urbanicity | ||||||

| Raised in rural area | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Raised in suburb/town | 1.24 | (0.81–1.90) | 0.31 | 2.58 | (1.44–4.63) | < 0.01 |

| Raised in city | 1.43 | (1.05–1.95) | < 0.05 | 5.42 | (3.27–8.98) | <0.001 |

| Religiosity | ||||||

| Important as a child | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Not important | 1.45 | (0.99–2.12) | 0.06 | 2.54 | (1.68–3.84) | < 0.001 |

| Drinking | ||||||

| Before initiation | 1 | 1 | ||||

| After initiation | 1.54 | (1.11–2.13) | < 0.01 | 8.08 | (3.96–16.49) | < 0.001 |

| First marriage | ||||||

| After marriage | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Before marriage | 3.67 | (1.33–10.11) | < 0.01 | 0.66 | (0.31–1.40) | 0.27 |

| First employment | ||||||

| After employed | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Before employed | 0.84 | (0.56–1.26) | 0.40 | 1.59 | (0.85–3.00) | 0.15 |

| Familial variables | ||||||

| Father’s education | ||||||

| 0–8 yrs | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 9–10 yrs | 1.17 | (0.85–1.60) | 0.34 | 2.78 | (1.54–5.01) | < 0.01 |

| 11+ yrs | 1.29 | (0.99–1.69) | 0.06 | 4.20 | (2.46–7.15) | < 0.001 |

| Closeness to parents | ||||||

| Close to both | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Close to one | 1.04 | (0.77–1.41) | 0.78 | 1.65 | (0.92–2.96) | 0.09 |

| Close to neither | 1.12 | (0.78–1.62) | 0.53 | 2.53 | (1.30–4.93) | < 0.01 |

| Parental antisocial behavior | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.73 | (0.94–3.16) | 0.08 | 2.28 | (1.39–3.75) | < 0.01 |

| Parental alcoholism | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.17 | (0.74–1.84) | 0.49 | 2.52 | (1.61–3.92) | < 0.001 |

| Parental anxiety or depression | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.06 | (0.67–1.69) | 0.79 | 1.68 | (0.97–2.91) | 0.06 |

| Psychiatric history | ||||||

| Externalizing behavior | ||||||

| 0 symptoms | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1 symptoms | 1.57 | (1.16–2.21) | < 0.01 | 3.79 | (2.10–6.85) | < 0.001 |

| 2+ symptoms | 1.82 | (1.22–2.70) | < 0.01 | 6.98 | (4.42–11.02) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | ||||||

| Before onset | 1 | 1 | ||||

| After onset | 5.50 | (2.56–11.83) | < 0.001 | 10.80 | (2.49–46.87) | < 0.01 |

| Mood disorder | ||||||

| Before onset | 1 | 1 | ||||

| After onset | 1.58 | (1.00–2.49) | < 0.05 | 1.47 | (0.93–2.32) | 0.09 |

| Anxiety disorder | ||||||

| Before onset | 1 | 1 | ||||

| After onset | 1.08 | (0.61–1.92) | 0.78 | 1.46 | (0.83–2.57) | 0.19 |

Odds ratios adjusted (aORs) for the underlying age-specific hazard function for smoking initiation.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of regular smoking in women by birth cohorta,b

None of the familial risk factors was significant in men. In women, however, greater paternal education, not feeling close to both parents, parental antisocial behavior and parental alcoholism increased the risk of smoking initiation. In both genders, the significant psychiatric history factors were childhood externalizing behavior and alcohol abuse, and the odds ratios were substantially larger in the women than in the men. Pre-existing mood disorder increased the risk of smoking initiation in men only.

The multivariable analyses indicated that in both men and women, onset of drinking and childhood externalizing problems were significantly associated with smoking initiation. Two other risk factors, not yet married and DSM-IV alcohol abuse, were also significant for men. In women, birth cohort and urbanicity (urban vs rural) remained significant. None of the familial risk factors was significant in the multivariable model for the women.

Dependence symptoms

Among smokers, almost two-thirds (61.7%) of men and one-half (47.1%) of women developed dependence symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms were the most common (41.7% of male and 34.5% of female smokers), while continued use despite problems (31.3% and 23.2%, respectively) and a persistent desire to quit (24.2% and 16.0%, respectively) were less frequently reported.

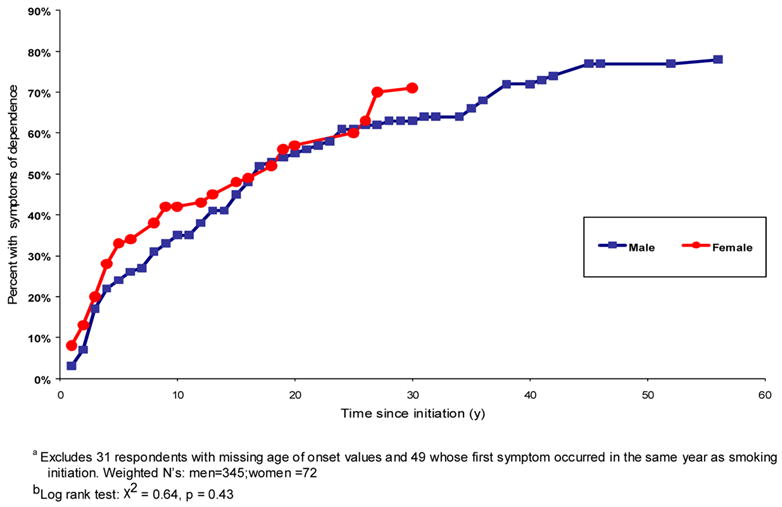

The cumulative incidence curves for first dependence symptom were steepest during the first 4 years after initiation and increased more gradually thereafter (see Figure 3). The median time from smoking initiation to the first reported symptom among smokers was 17 years in both genders. In the youngest birth cohort (1965–1984), the median time to first symptom was 9 years for men and 6 years for women. In the subgroup within the youngest birth cohort having lifetime dependence symptoms, the median time was the same for men (9 years) but shorter for women (4 years).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of first symptom of nicotine dependence since initiation of regular smokinga,b

The risk factors were first analyzed separately controlling only for time since smoking intiation (Table 3). In male smokers, younger birth cohort, being raised in a suburban area, 2 or more childhood externalizing symptoms, and prior alcohol abuse increased the risk of dependence. These risk factors remained significant in the multivariable model. In female smokers, being born into the youngest birth cohort, parental anti-social behavior, parental alcoholism, and personal history of alcoholism significantly increased the risk of dependence. With the exception of parental alcoholism in women, these risk factors remained significant in the multivariable models.

Table 3.

Risk factors for transition to first dependence symptom among lifetime smokers: significant associations

| Males (weighted N=559) | Females (weighted N=154) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 1a | Model 2b | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Birth cohort | aORa | 95% CI | P | aORa | 95% CI | P | aORa | 95% CI | P | aORa | 95% CI | P |

| <=1944 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 1945–1964 | 1.77 | (1.12–2.80) | <0.05 | 1.57 | (1.01–2.43) | <0.05 | -- | -- | ||||

| 1965–1984 | 4.32 | (2.49–7.52) | <0.001 | 3.67 | (2.08–6.48) | <0.001 | 17.08 | (3.13–93.27) | <0.01 | 13.61 | (2.28–81.27) | <0.01 |

| Urbanicity | ||||||||||||

| Raised in rural area | 1.00 | 1.00 | -- | -- | ||||||||

| Raised in suburb/town | 1.88 | (1.44–3.12) | <0.05 | 1.68 | (1.06–2.68) | <0.05 | -- | -- | ||||

| Raised in urban area | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||||||

| Parental anti-social behavior | ||||||||||||

| No | -- | -- | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Yes | -- | -- | 2.80 | (1.55–5.05) | <0.01 | 2.63 | (1.50–4.63) | <0.01 | ||||

| Parental alcoholism | ||||||||||||

| No | -- | -- | 1.00 | -- | ||||||||

| Yes | -- | -- | 2.07 | (1.14–3.77) | <0.05 | -- | ||||||

| Externalizing behavior | ||||||||||||

| 0 symptoms | 1.00 | 1.00 | -- | -- | ||||||||

| 1 symptom | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||||||

| 2+ symptoms | 2.44 | (1.58–3.79) | <0.001 | 1.83 | (1.16–2.88) | <0.05 | -- | -- | ||||

| Alcohol abuse | ||||||||||||

| Before onset | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| After onset | 2.59 | (1.75–3.82) | <0.001 | 1.72 | (1.08–2.72) | <0.05 | 3.43 | (1.80–6.52) | <0.001 | 2.49 | (1.32–4.70) | <0.01 |

Odds ratios adjusted for years since initiation of regular smoking (non-significant risk factors eliminated from the model)

Odds ratios adjusted for years since initiation of regular smoking and other risk factors (non-significant risk factors eliminated from the model).

Additional analysis

Because of potential survivor bias in the older segment of the population, we reestimated the bivariate associations in the subgroup of respondents born after 1944. The pattern of results was similar to those of the entire population although with the reduction in effective sample size, some of results were similar in magnitude but not statistically significant. (Tables available from the author.)

Discussion

We found that smoking initiation in Ukraine occurred primarily during the teenage years, and 4 in 5 men and 1 in 5 women became regular smokers. We then selected variables identified as antecedent risk factors in Western epidemiologic research. These risk factors included personal characteristics, family background, and psychiatric history. The most important risk factors (p<0.01) for men were youngest birth cohort (1965–1984), DSM-IV alcohol abuse, not yet married, childhood externalizing behaviors, and drinking. In women, they were younger birth cohorts, urbanicity, lack of religiosity in childhood, drinking, paternal education, feeling close to neither parent, parental antisocial behavior and alcoholism, childhood externalizing behaviors, and alcohol abuse. Two-thirds of male and one-half of female smokers developed dependence symptoms, but in the youngest bith cohort (with the shortest recall period), the latency from regular smoking to first dependence symptom was shorter for women (6 years on average) than for men (9 years). In both genders, birth cohort and alcohol abuse were independent risk factors for onset of dependence.

The consistency of our prevalence findings with previous research in post-Soviet countries,[6] especially Ukraine,[2] supports the reliability of the Ukraine-WMH. On the other hand, our analysis relied on retrospectively reported ages of onset. Recall error and survivor bias could have intruded on our findings. Recall error was reduced in the WMH-CIDI through the use of age probes specifically included throughout the WMH-CIDI to help respondents place events in time.[29] Although these probes could not correct completely for recall bias or telescoping, the age-of-onset distributions of all key variables were plausible. Survivor bias is a concern since smoking is associated with early mortality, especially in older men. Thus, it was instructive that the pattern of results reported in this paper was similar for respondents born after 1944. The lag time between smoking and dependence symptoms is also subject to recall and survivor bias, but in addition it may reflect the DSM-IV criteria requiring a problem orientation as opposed to criteria based only on behaviors (such as smoking within an hour of wakening).

The present analysis sheds new light on three points. First, the gender disparity in the rate of smoking initiation in Ukraine was greater than in the West.[11] Our finding is consistent with gender differences in heavy alcohol use and abuse in this sample[26][28] and with reports on current smoking in post-Soviet countries.[2][6] Furthermore, we also found gender differences in some risk factors associated with regular smoking. That is, while a predisposition to antisocial and drinking behavior was important in both genders, in women, younger birth cohort and environmental factors (i.e., being born after 1964 and raised in an urban area) were also important, as previously shown.[2][31]

Second, women in the youngest cohort were 26 times more likely to become regular smokers than their eldest counterparts, thus signifying a worrisome trend.[2] As more women smoke, and smoke for longer periods of time, the female prevalence of dependence symptoms will increase greatly. Throughout the 20th century, there have been periods of increased smoking among women in other countries. In the USA, smoking in women increased from 6% in 1924 to 34% in 1965.[32] In Spain, it increased from 2% in 1950 to 39% in 1997 in women ages 16–44.[33] In these and other settings, women with higher education and greater social status were at greater risk during the early phase of the epidemic. Consistent with this, greater paternal education was positively associated with smoking initiation in women in our sample. Over time, as smoking became more common in Western countries, increased risk was associated with being poor and less educated.[34] Thus, the socioeconomic risk factors for female initiation and dependence in Ukraine in 2002 will change if the rate of smoking in women continues to increase.

The third point is that pre-existing alcoholism, but not anxiety or depression, were significantly associated with the onset of dependence symptoms in Ukraine. Thus, while diagnosable alcohol, depression and anxiety disorders were risk factors for nicotine dependence in the USA,[15][20] only alcohol abuse predicted dependence symptoms in smokers in our survey. Conceivably, we may have had insufficient power to detect other relationships. However, the odds ratios for the internalizing disorders were considerably smaller than those reported in the USA.[15]

In conclusion, the Ukraine-WMH found a high rate of smoking initiation and transition to dependence symptoms, particularly in men and younger women. These behaviors were associated with externalizing behaviors and alcohol use and misuse, but not with internalizing mental health problems. The early onset of smoking and high risk of developing dependence symptoms suggest that interventions should start in young adolescence. Future studies are needed to determine the generalizability of these findings to other post-Soviet societies.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Significant risk factors for smoking initiation in full multivariable models

| Males (weighted N=770)

|

Females (weighted N=941)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aORa | 95% CI | P | aORa | 95% CI | P | |

| Personal variables | ||||||

| Birth cohort | ||||||

| <=1944 | -- | 1 | ||||

| 1945–1964 | 5.17 | (2.21–12.09) | <0.001 | |||

| 1965–1984 | 15.83 | (6.53–38.39) | <0.001 | |||

| Urbanicity | ||||||

| Raised in rural area | -- | 1 | ||||

| Raised in suburb/town | 1.77 | (0.90–3.49) | 0.10 | |||

| Raised in city | 3.44 | (2.01–5.89) | <0.001 | |||

| Drinking | ||||||

| Before initiation | 1 | 1 | ||||

| After initiation | 1.44 | (1.02–2.03) | <0.05 | 15.60 | (6.19–39.30) | <0.001 |

| First marriage | ||||||

| After marriage | 1 | -- | ||||

| Before marriage | 3.30 | (1.33–8.17) | <0.05 | |||

| Psychiatric history | ||||||

| Externalizing behavior | ||||||

| 0 symptoms | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1 symptoms | 1.52 | (1.13–2.05) | <0.01 | 2.14 | (1.14–4.01) | <0.05 |

| 2+ symptoms | 1.68 | (1.12–2.52) | <0.05 | 4.22 | (2.74–6.48) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Abuse | ||||||

| Before onset | 1 | -- | ||||

| After onset | 4.21 | (1.90–9.33) | <0.001 | |||

Non-significant risk factors were eliminated from the adjusted model; the odds ratios were also adjusted for the age-specific hazard function

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH61905, Evelyn J. Bromet PI). The survey was conducted as part of the WHO World Mental Health Survey consortium directed by Ronald C. Kessler (Harvard University) and T. Bedirhan Ustun (World Health Organization). The authors thank Volodymyr Paniotto, Valeriy Khmelko and Victoria Zakhozha (Kiev International Institute of Sociology) and Julia Pievskaya (Ukrainian Psychiatric Association) for conducting the field work; Inna Korchak, Roxalana Mykhaylyk, Margaret Bloom, and Svetlana Stepukhovich for translating the instrument and manuals; and Joseph Ortiz for statistical advice. Special thanks go to the interviewers and participants for their dedication and diligence.

Footnotes

Statement of Competing Interest

None of the listed authors has received research funds, funds from a staff member, or any fee (e.g., for conducting a symposium, speaking, organizing education, or consulting) that would compromise their objectivity or lead to their financial gain or loss as a result of this manuscript being published. No author has membership, stocks, or a financial interest in an organization that would financially gain or lose as a result of publication. Thus, we declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gilmore AB, McKee M. Tobacco and transition: an overview of industry investments, impact and influence in the former Soviet Union. Tob Control. 2004;13:136–42. doi: 10.1136/tc.2002.002667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilmore AB, McKee M, Telishevska M, Rose R. Epidemiology of smoking in Ukraine, 2000. Prev Med. 2001;33:453–61. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilmore AB, McKee M, Rose R. Prevalence and determinants of smoking in Belarus: A national household survey, 2000. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:245–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1017999421202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKee M, Rose R. Smoking and drinking in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus: Studies in Public Policy. Glasgow, Scotland: University of Strathclyde; 2000. pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M. Mortality from smoking in developed countries 1980–2000. 2006:482–492. www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/~tobacco.

- 6.Gilmore A, Pomerleau J, McKee M, Rose R, Haerpfer CW, Rotman D, et al. Prevalence of smoking in 8 countries of the former Soviet Union: Results from the Living Conditions, Lifestyles and Health Study. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2177–87. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parna K, Rahu K, Rahu M. Patterns of smoking in Estonia. Addiction. 2002;97:871–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pakriev S, Shlik J. Patterns of tobacco use in rural Udmurtia. Tob Control. 2001;10:85–6. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pomerleau J, Gilmore A, McKee M, Rose R, Haerpfer CW. Determinants of smoking in eight countries of the former Soviet Union: Results from the Living Conditions, Lifestyles and Health Study. Addiction. 2004;99:1577–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pudule I, Grinberga D, Kadziauskiene K, Abaravicius A, Vaask S, Robertson A, et al. Patterns of smoking in the Baltic republics. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:277–82. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.5.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hiripi E, Kessler R. Nicotine dependence in the United States: Prevalence, trends and smoking persistence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:810–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen K, Kandel DB. The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:41–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilpin EA, Lee L, Pierce JP. How have smoking risk factors changed with recent declines in California adolescent smoking? Addiction. 2005;100:117–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CY, Dormitzer CM, Bejarano J, Anthony JC. Religiosity and the earliest stages of adolescent drug involvement in seven countries of Latin America. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1180–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breslau N, Novak SP, Kessler RC. Psychiatric disorders and stages of smoking. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saules KK, Pomerleau CS, Snedecor SM, Mehringer AM, Shadle MB, Kurth C, et al. Relationship of onset of cigarette smoking during college to alcohol use, dieting concerns, and depressed mood: Results from the Young Women’s Health Survey. Addict Behav. 2004;29:893–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juon HS, Ensminger ME, Sydnor KD. A longitudinal study of developmental trajectories to young adult cigarette smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:303–14. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kandel DB, Kiros GE, Schaffran C, Hu MC. Racial/ethnic differences in cigarette smoking initiation and progression to daily smoking: A multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:128–35. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conwell LS, O’Callaghan MJ, Andersen MJ, Bor W, Najman JM, Williams GM. Early adolescent smoking and a web of personal and social disadvantage. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:580–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dierker LC, Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR, Flaherty BP, Stolar M. Association between psychiatric disorders and the progression of tobacco use behaviors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1159–67. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van den Bree MB, Whitmer MD, Pickworth WB. Predictors of smoking development in a population-based sample of adolescents: A prospective study. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:172–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Giles WH, Williamson DF, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA. 1999;282:1652–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frohlich KL, Potvin L, Gauvin L, Chabot P. Youth smoking initiation: Disentangling context from composition. Health Place. 2002;8:155–66. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(02)00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrell JS, Bangdiwala SI, Deng S, Webb JP, Bradley C. Smoking initiation in youth: The roles of gender, race, socioeconomics and developmental status. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23:271–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu MC, Davies M, Kandel DB. Epidemiology and correlates of daily smoking and nicotine dependence among young adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:299–308. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bromet EJ, Gluzman SF, Paniotto VI, Webb CP, Tintle NL, Zakhozha V, et al. Epidemiology of psychiatric and alcohol disorders in Ukraine: Findings from the Ukraine World Mental Health Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:681–90. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webb CPM, Bromet EJ, Gluzman S, Tintle NL, Schwartz JE, Kostyuchenko S, et al. Epidemiology of heavy alcohol use in Ukraine: Findings from the World Mental Health Survey Alcohol. Alcohol. 2005;40:327–35. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.SUDAAN Version 8.0.2. North Carolina: Research Triangle Park; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bobak M, Gilmore A, McKee M, Rose R, Marmot M. Changes in smoking prevalence in Russia, 1996–2004. Tob Control. 2006;15:131–5. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MMWR. Women and smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shafey O, Fernandez E, Thun M, Schiaffino A, Dolwick S, Cokkinides V. Cigarette advertising and female smoking prevalence in Spain, 1982–1997: Case studies in International Tobacco Surveillance. Cancer. 2004;100:1744–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiaffino A, Fernandez E, Borrell C, Salto E, Garcia M, Borras JM. Gender and educational differences in smoking initiation rates in Spain from 1948 to 1992. Eur J Public Health. 2003;13:56–60. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.