Abstract

Pmel17 is a ≈100 kDa pigment cell specific glycoprotein that plays a crucial part in the morphogenesis of melanosome precursors. Anti-Pmel17 immunoprecipitates from metabolically pulse labeled melanoma cells and melanocytes contain, in addition to full-length Pmel17, a glycoprotein that migrates with a lower relative molecular weight. Here we show that this glycoprotein is encoded by an mRNA that results from alternative splicing of the human Pmel17 gene from which a cryptic intron is excised. Immunoprecipitation recapture experiments showed that this glycoprotein contained both the N- and C-termini of full-length Pmel17. Sequence analysis of cDNA corresponding to the alternatively spliced form reveals the loss of three of 10 imperfect direct repeats from the central region of the lumenal domain. The product of the splice variant is processed with similar kinetics to full-length Pmel17, and localizes similarly to late endosomes when expressed ectopically in nonpigment cells. We speculate that truncation of the repeat region within Pmel17 alters either fibrillogenic activity or the interaction of Pmel17 with melanin intermediates. The expression of an alternatively spliced product may furthermore affect the cohort of peptides generated for recognition of melanoma cells by tumor-directed T lymphocytes.

Keywords: fibril formation, gp100, melanoma, melanosome, silver

Melanin biosynthesis and storage are sequestered within lysosome-related organelles of melanocytes and eye pigment epithelia called melanosomes (Orlow, 1995; Marks and Seabra, 2001). In order to carry out their unique function, melanosomes harbor a cohort of glycoproteins that are expressed only in pigment cells. These proteins include enzymes, such as tyrosinase and the tyrosinase-related proteins Tyrp1 and Dopachrome tautomerase, as well as structural proteins and transporters that modulate the morphology, intralumenal microenvironment, and function of the melanosome (Sturm et al, 2001). Melanosome activity and morphology and the type of melanins produced can be modulated by the expression or modification of various components through gene regulatory mechanisms or mutation (Hearing, 1999, 2000). This kind of modulation can affect pigmentation in primary melanocytes or tumorigenicity and/or immunogenicity in transformed melanocytes (Kawakami et al, 2000; Overwijk and Restifo, 2000; Slingluff et al, 2000).

Pmel17 (also known as gp100 or the product of the Silver locus) is a type I integral membrane glycoprotein that localizes to the lumen of melanosome precursors (Kwon et al, 1987; Orlow et al, 1993; Kobayashi et al, 1994; Lee et al, 1996). It is highly expressed by melanocytes, and serves as a common target for tumor-directed T lymphocytes in patients with melanoma (Kawakami et al, 1998a). We have shown that Pmel17 aligns with the intralumenal fibers that are characteristic of melanosomes and their precursors (Berson et al, 2001; Raposo et al, 2001), that ectopic expression of Pmel17 alone is sufficient to induce the formation of similar fibers in nonpigment cells (Berson et al, 2001), and that a lumenal domain fragment copurifies with the fibers (Berson et al, 2003). Others have implicated roles for Pmel17 in immobilizing the melanin intermediate, DHICA (Chakraborty et al, 1996; Lee et al, 1996), and in detoxifying DHICA and/or other melanin intermediates within the melanocyte (Quevedo et al, 1981; Spanakis et al, 1992); both of these activities may be associated with the fibrillogenic activity of Pmel17, resulting in immobilization of melanin intermediates on fibrous structures. The hypopigmentation of silver mice, which harbor a truncated Pmel17 molecule (Martínez-Esparza et al, 1999), indicates that an intact cytoplasmic domain is required for Pmel17 function. The structural features of the Pmel17 lumenal domain that effect function within melano-somes, however, are not known. During its biosynthesis within melanocytes, Pmel17 undergoes complex processing, involving cleavage within the lumenal domain, which is required for its fibrillogenic activity (Berson et al, 2001, 2003), suggesting that its function may require conformational changes induced by proteolytic processing of this domain. The only other recognizable features of the lumenal domain are (1) a small region with homology to polycystic kidney disease (PKD) repeat regions within the PKD 1 protein (Hughes et al, 1995), and (2) 10 tandem repeats of a 13 amino acid proline- and glutamate-rich sequence immediately downstream of the PKD repeats (Kwon et al, 1991).

Two distinct Pmel17 products resulting from alternative splicing of the mRNA have been described in human melanocytic cells (Adema et al, 1994; Maresh et al, 1994; Bailin et al, 1996; Kim et al, 1996). These two forms differ by only seven amino acids, encoded by a 21 bp insertion resulting from use of an alternative splice acceptor site in exon 10 of the Pmel17 gene, within the juxtamembrane region of the lumenal domain (Bailin et al, 1996; Kim et al, 1996). Here, we describe a second splice variation that occurs in human melanocytic cells and results in the production of a smaller Pmel17 product containing a deletion within the lumenal domain tandem repeat region. We speculate that expression of this truncated Pmel17 may alter oligomerization or melanin binding properties and thereby modulate melanosome structure and/or function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfection

Human melanoma cell lines MNT-1 and 1011-mel were cultured in Dulbecco minimal Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% AIM-V medium, 20% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, nonessential amino acids, and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin). Melan-a (Bennett et al, 1989) cells and the mouse T cell hybridoma, DO11.10 (Roehm et al, 1982) were cultured as described. Primary melanocytes, a kind gift from Dr M. Herlyn and R. Finko, were cultured as described (Raposo et al, 2001). HeLa cells were cultured as described (Calvo et al, 1999), and transfected using FuGene-6 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Indiana) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with 2 µg of total plasmid DNA (0.2 µg of specific plasmid DNA and 1.8 µg of empty pCI expression vector).

Antibodies

αPmel-N and αPmel-I antibodies were raised against peptides corresponding to N-terminal or internal regions of the Pmel17 lumenal domain. Peptides were synthesized with the following sequences, representing the indicated residues from full-length Pmel17 with an additional N-terminal cysteine added for coupling to keyhole limpet hemocyanin using m-maleimidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester: Pmel-N, H2N-(C)TKVPRNQDWLGVSRQLR-CO2H (residues 24–40); Pmel-I, H2N-(C)QVPTTEVVGTTPGQAPTAE-CO2H (residues 326–344). Peptide synthesis, coupling, rabbit immunization and production were performed by Genemed Synthesis (South San Francisco, California). Anti-peptide antibodies were affinity purified by passing sodium sulfate precipitated serum through a column in which peptides were coupled to SulfoLink gel (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, Illinois) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Antibodies were eluted with 0.1 M glycine pH 2.7, neutralized with Tris base, and dialyzed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.02% sodium azide. Other antibodies and their sources were as follows: αPEP13h (referred to here as αPmel-C for simplification), to Pmel17 cytoplasmic domain (Berson et al, 2001); HMB50 and HMB45, to Pmel17 lumenal domain (Lab Vision, Fremont, California); and H4A3, to LAMP1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, Iowa). Chromophore-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, Pennsylvania) or from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, Alabama).

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (reverse transcriptase–PCR) and cloning of alternative splice forms

mRNA was isolated from MNT-1, 1011-mel, HeLa, melan-a, cultured primary human melanocytes, or D011.10 mouse T cell hybridoma cells using the RNEasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California). For reverse transcriptase reactions, RNA (15 µg) was incubated with reverse primers, as indicated, heated to 90°C, cooled to 52°C for 15 min, and then incubated with Avian Myeloblastosis Virus reverse transcriptase and appropriate buffers according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin). Control reactions lacked reverse transcriptase. After ethanol precipitation, 12.5% of each reaction was subjected to PCR amplification with indicated primers for 30 cycles (1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 2.5 min at 72°C). Parallel reactions were done using 100 ng of plasmid DNA with Pmel17-l insert. Reaction products were fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis alongside 100 bp markers (Life Technologies, Rockville, Maryland) and visualized after staining with ethidium bromide. Triads of PCR reactions with template from reverse transcriptase reactions that contained or lacked reverse transcriptase enzyme or with plasmid template are shown at identical exposures for each triad. Primers are indicated in Table I.

Table I.

Oligonucleotides used for reverse transcription–PCR

| No. | Derivation | Position in cDNAa | Sequence of oligonucleotideb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 144 | hPmel17 | 451–474 | 457GCA TCT TCC CTG ATG GTG474 |

| 145 | hPmel17 | 855–872 | 855GGA GAC AGT AGT GGA ACC872 |

| 147 | hPmel17 | 1654–1670 | 1654CAT CGC CAG GGT GCC AG1670 |

| 166 | hPmel17 | 1938–1952 | GGG CTC ACC TGG CAA 1938AGG CGC AGA CTT ATG1952 |

| 171 | hPmel17 | 1454–1492 | 1454C ACC TTA AGG CTG GTG CAG CAA CAA GTC CCC CTG GAT TG1492 |

| 172 | hPmel17 | 1492–1454 (R) | 1492CA ATC CAG GGG GAC TTG TTG CTG CAC CAG CCT TAA GGT G1454 |

| 356 | hPmel17 | 1998–1983 (R) | tc ttt tct aga tt1998A GTG ACT GCT GCT ATG1983 |

| 398 | hPmel17 | 2119–2102 (R) | tgt ttt cta ga2119g ttt ctg tca act cca gg2102 |

| 232 | mGAPDH | 47–69 | 47ATG GTG AAG GTC GGT GTG AAC GG69 |

| 233 | mGAPDH | 1045–1018 (R) | 1045CTC CTT GGA GGC CAT GTA GGC CAT CAG G1018 |

| 319 | hRab5a | 57–73 | atac cag atc ttg 57ATG GCT AGT CGA GGC GC73 |

| 321 | hRab5a | 704–682 (R) | aaga tct aga 704TTA GTT ACT ACA ACA CTG ATT CC682 |

| 418 | mPmel17 | 902–921 | 902GT GGT TCC TCC CCA GTC CCG921 |

| 419 | mPmel17 | 1320–1302 (R) | 1320CAG GGG AAC TTG TCT CTT C1302 |

Reverse primers are indicated by (R).

Superfluous sequences that are not directly homologous to the cDNA are indicated by italics.

For sequencing and subcloning, PCR reaction products using primers 144 and 398 were fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis, purified, and subcloned into pCR2.1 by TA cloning (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). Clones with appropriate sized EcoRI inserts for Pmel17-s and Pmel17-i were sequenced by automated dideoxy sequence analysis (Children’s Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). To reconstitute a full-length cDNA for hPmel17-s, the NcoI–XbaI fragment from pCR2.1-hPmel17-s was used to replace the corresponding fragment in full-length hPmel17-l subcloned in pSP72 (Promega). Similarly, full-length hPmel17-i was generated by using the BstXI–XbaI fragment from pCR2.1-hPmel17-i to replace the corresponding fragment in pSP72-hPmel17-l. From the resultant pSP72 plasmids containing full-length products, EcoRI–XbaI fragments containing the entire reading frame of hPmel17-s or hPmel17-i were subcloned into the pCI mammalian expression vector (Promega). Sequences of all inserts were verified by automated dideoxy sequencing.

Metabolic pulse chase and immunoprecipitation analyses

Melanoma cells, melanocytes, or transfected HeLa cells were metabolically labeled with 35S-methionine/cysteine as described (Berson et al, 2000) for 20 to 30 min, then chased for 0 to 4 h as indicated. Cell lysates in 1% Triton X-100 were prepared and immunoprecipitated as described (Berson et al, 2000). For immunoprecipitation/recapture experiments, immunoprecipitated products were released by addition of 50 µL of 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and heating to 100°C for 5 min. Samples were then brought to 0.5 mL with lysis buffer to dilute the SDS, and subjected to a second round of immunoprecipitation with indicated antibodies. All immunoprecipitates were fractionated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and analyzed on a Molecular Dynamics Storm Phosphor Imaging system using ImageQuant software (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, New Jersey).

Western blotting analyses

Whole cell lysates of transfected HeLa cells were treated or not with endoglycosidase H (EndoH, New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), fractionated by SDS–PAGE, transferred to reinforced nitrocellulose membranes, probed with αPmel-N or αPmel-C antibodies, and developed with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin and ECF enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences) as described previously (Berson et al, 2001).

Immunofluorescence microscopy analyses

Transiently transfected HeLa cells expressing hPmel17-l, hPmel17-i, or hPmel17-s were fixed with 2% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and stained as described (Calvo et al, 1999) with antibodies to Pmel17 (HMB50; IgG2a) and to Lamp1 (H4A3; IgG1), followed by isotype-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate or Texas Red. Cells were analyzed on a Leica Microsystems (Bannockburn, Illinois) DM IRBE microscope, and images were captured, analyzed, and processed for deconvolution using a Hamamatsu (Hamamatsu, Japan) Orca digital camera and Improvision (Lexington, Massachusetts) OpenLab software.

Sequence analyses

Sequence formatting and comparisons were done using DNAStar (Madison, Wisconsin) or DNA Strider. The following GenBank accession nos were used to obtain cDNA sequences for Pmel17 orthologs from the NCBI database: mouse (Mus musculus) Silver, accession no. NM_021882; chicken (Gallus gallus) MMP115, accession no. D88348; bovine (Bos taurus) RPE1, accession no. M81193; and horse (Equus caballus) Pmel17, accession no. AF076780.

RESULTS

Band X is expressed in normal melanocytes in addition to melanoma cells

Anti-Pmel17 immunoprecipitates of cell lysates from metabolically pulse labeled MNT-1 human melanoma cells contained, in addition to the ≈100 kDa band representing full-length Pmel17, a band with faster migration (≈95 kDa; Berson et al, 2001). This band, referred to as “band X” was: (1) precipitable with either of two distinct antibodies to Pmel17 (HMB50, which recognizes the lumenal domain, and αPmel-C, which binds to the cytoplasmic domain), (2) susceptible to digestion with EndoH (indicating residence within a pre-Golgi compartment), and (3) not obvious in lysates from cells that were chased in the presence of excess unlabeled methionine (Berson et al, 2001; see also Berson et al, 2003). The band was distinguished from the proteolytic product, Mα, by virtue of its slightly distinct migration in gels and by its susceptibility to digestion with EndoH; Mα, which appears only after the chase, is resistant to EndoH digestion. Furthermore, band X was not observed in lysates of transfected HeLa cells expressing Pmel17 from a transgene (Berson et al, 2001).

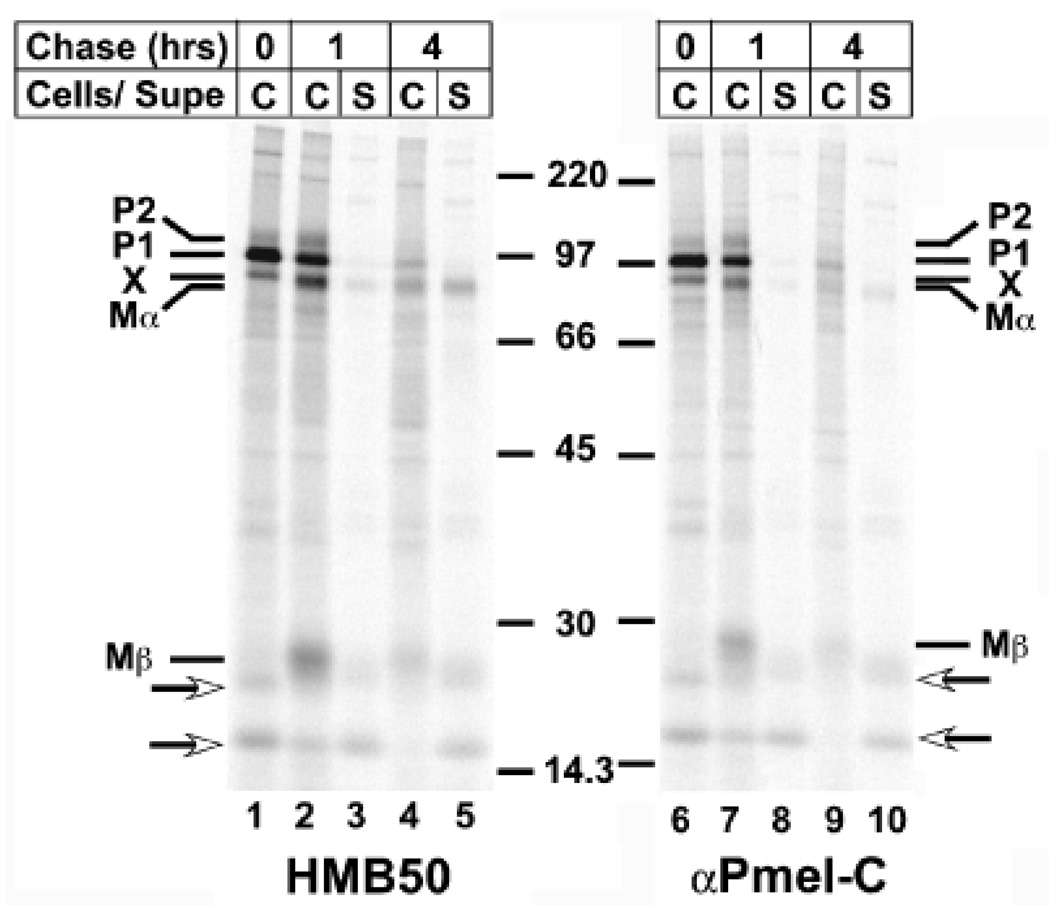

To determine whether band X was unique to MNT-1 cells or represented a coprecipitating product present in untransformed cells, we subjected cultures of normal primary human melanocytes to a similar metabolic pulse/chase analysis. As shown in Fig 1, a similar pattern of immunoprecipitable products was observed from Triton X-100 cell lysates of these cells as previously observed in MNT-1 cells. Thus, band X was present in addition to full-length, core glycosylated “P1” Pmel17 at the pulse. During the chase, both were reduced in intensity and a slightly faster migrating Mα band appeared concomitantly with the ≈28 kDa Mβ and the faint, diffuse slower migrating P2 form representing the Golgi modified full-length protein (note that unlike P1 and band X, the migration of Mα and P2 varies among melanoma cells and primary melanocytes most likely due to differential terminal glycosylation; Vogel and Esclamado, 1988; Chiamenti et al, 1996). Although reduced in intensity, P1 persists throughout the chase in all cells, likely due to inefficient exit from the endoplasmic reticulum (Vogel and Esclamado, 1988; Adema et al, 1994; Kobayashi et al, 1994; Berson et al, 2001, 2003). All bands were precipitable with both HMB50 and αPmel-C, indicating that lumenal and cytoplasmic domains were both present (and linked in the case of Mα/Mβ). Similar results were obtained in a second primary human melanocyte culture and in 1011-mel human melanoma cells. By contrast, only one band corresponding to the full-length product was observed in immunoprecipitates of pulse-labeled mouse melanocytic cell lines melan-a and melan-a3 (unpublished data). Thus, band X represents a coprecipitating product present in normal and transformed human melanocytes but absent in mouse melanocytes.

Figure 1. Processing of Pmel17 and appearance of band X in untransformed human melanocytes.

Primary human foreskin-derived melanocytes were pulse labeled with 35S-methinonine/cysteine for 30 min and then chased for 0, 1, or 4 h in the presence of excess unlabeled methionine and cysteine. Triton X-100 cell lysates (C) or culture supernatants (S) were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to the lumenal (HM50, lanes 1–5) or cytoplasmic (αPmel-C, lanes 6–10) domains of Pmel17, and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and phosphorimaging. The position of molecular weight markers is indicated in the middle. The positions of the core glycosylated precursor (P1), band X (X), the Golgi-processed P2 form, and the proteolytic products Mα and Mβ are indicated. Arrows, nonreproducible bands that most likely reflect post-lysis degradation products.

Band X contains the N- and C-termini of Pmel17

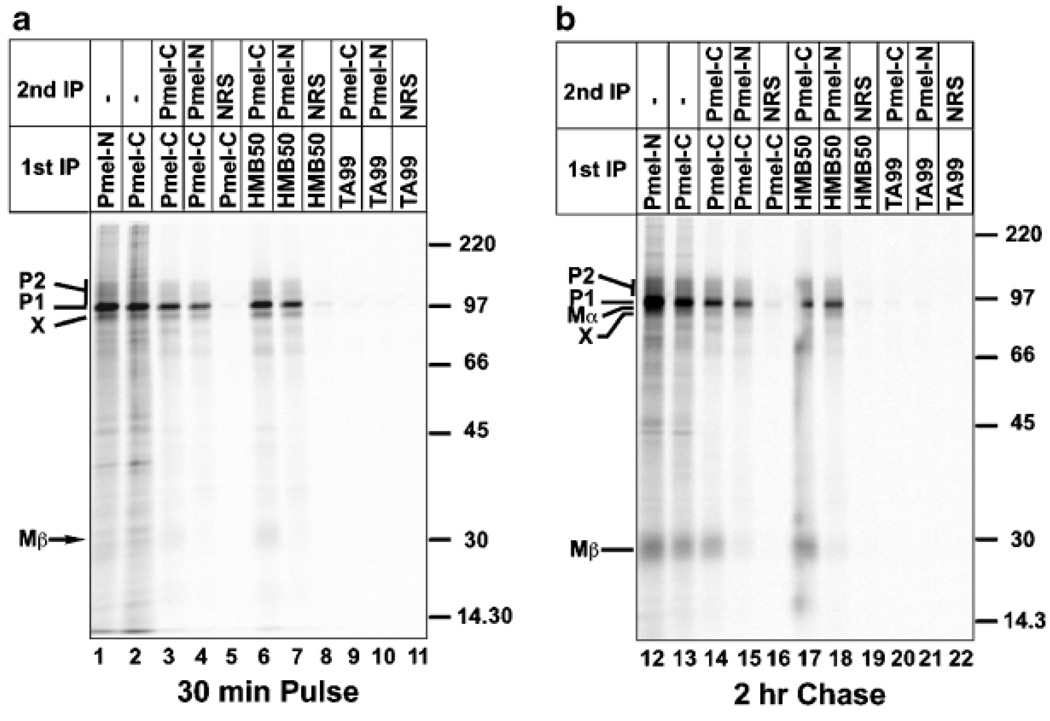

To determine whether band X represented a modified form of Pmel17 or a coprecipitating product, we subjected radio-labeled cell lysates to a two-step immunoprecipitation recapture protocol using anti-Pmel17 antibodies. Pmel17 was first immunoprecipitated using αPmel-C or HMB50 under nondenaturing conditions from Triton X-100 lysates of 35S-methionine pulse-labeled MNT-1 cells (Fig 2a, lanes 1 and 2) or cells chased for 2 h in the absence of 35S-methionine (Fig 2b, lanes 12 and 13). Material from these primary immunoprecipitates was then eluted by boiling in the presence of SDS and a reducing agent; this treatment not only dissociates material from the antibodies, but also disrupts any potential complexes containing Pmel17 associated noncovalently or via disulfide bonds to other polypeptides. After removal of the beads, the SDS was diluted and eluates were subjected to a second round of immunoprecipitation using rabbit antibodies directed against peptides corresponding to the N- or C-terminus of Pmel17; because of the SDS treatment, only polypeptides directly recognized by these antibodies should be immunoprecipitated in the second step. As shown in Fig 2(a, lanes 3, 4, 6, and 7), band X is present in the second step immunoprecipitates using both anti-Pmel17 antibodies from lysates of pulse-labeled cells; it was also precipitable using the αPmel-I antibody to an intralumenal peptide (unpublished data). As a control, using lysates from cells chased for 2 h in the absence of radiolabel, Mα or Mβ were precipitable only with the N- or C-terminus-directed antibody, respectively (Fig 2b, lanes 14, 15, 17, and 18). No bands were recaptured using nonspecific antibodies in the second step (lanes 5, 8, 16, and 19) or antibodies to an irrelevant protein in the first step (lanes 9–11 and 20–22). From these data, we conclude that band X corresponds to a variant form of Pmel17 and that it contains both the N- and C-termini. We therefore refer to this product herein as Pmel17-s for short form. The data also indicate that Pmel17-s is distinct from the processed Mα cleavage product of Pmel17 (although Mα likely includes a product derived from Pmel17-s; see below).

Figure 2. Immunoprecipitation/recapture of band X using anti-Pmel17 antibodies.

MNT-1 cells were pulse labeled with 35S-methinonine/cysteine for 30 min and then chased for 0 (a) or 2 h (b) with excess unlabeled methionine and cysteine. Triton X-100 cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using the anti-Pmel17 antibodies αPmel-N (lanes 1 and 12), αPmel-C (lanes 2–5 and 13–16), or HMB50 (lanes 6–8 and 17–19), or the anti-Tyrp1 antibody TA99 (lanes 9–11 and 20–22). Material from the first immunoprecipitate was eluted by boiling with SDS and reducing agent, cooled, diluted with Triton X-100 lysis buffer, and subject to a second round of immunoprecipitation using normal rabbit serum (NRS; lanes 5, 8, 11, 16, 19, and 22) or the anti-Pmel17 antibodies αPmel-C (lanes 3, 6, 9, 14, 17, and 20) or αPmel-N (lanes 4, 7, 10, 15, 18, and 21). Material from the first round (lanes 1, 2, 12, and 13) or second round (all other lanes) of immunoprecipitation were fractionated by SDS–PAGE and analyzed by phosphorimaging. The position of molecular weight markers is indicated to the right of each gel, and the migration of the P1, P2, Mα, Mβ, and band X forms of Pmel17 are indicated. Note that (b) was exposed for a longer period of time than (a) in order to emphasize the Mα and Mβ bands.

Identification of an alternatively spliced, truncated form of Pmel17

The presence of both the N- and C-termini within the single Pmel17-s polypeptide indicates that Pmel17-s cannot be a proteolytic digestion product of full-length Pmel17. Furthermore, the fact that Pmel17-s and full-length Pmel17 continue to migrate differently following digestion with EndoH (Berson et al, 2001) excludes the possibility that the two products differ only by the degree of N-linked glycosylation. We therefore hypothesized that Pmel17-s was an alternative Pmel17 translation product derived from a truncated Pmel17 mRNA.

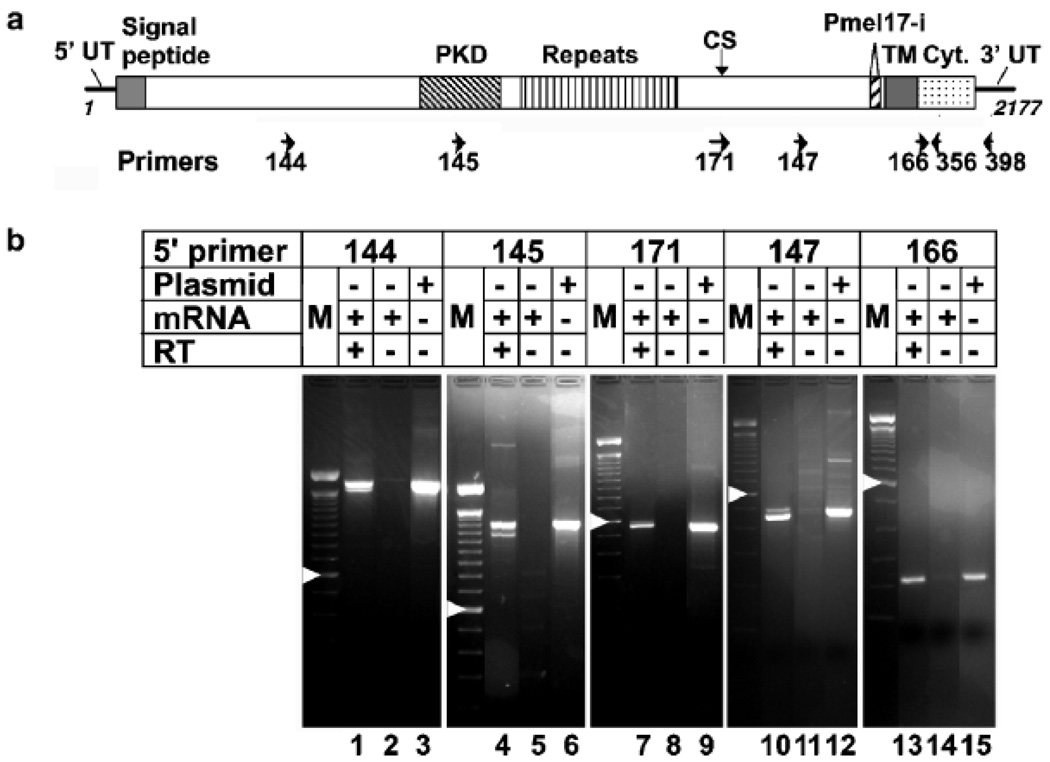

To test for the existence of such an mRNA species, we performed reverse transcriptase–PCR analyses of MNT-1 mRNA using primer sets corresponding to various portions of the Pmel17 coding region (see Table I, Fig 3a). As expected, a single band of ≈182 bp was detected using a primer set spanning the coding region for the cytoplasmic domain (Fig 3b, lanes 13–15). Using primer sets that spanned only the 3′ third of the Pmel17 coding region, two reverse transcriptase–PCR products could be observed differing by only approximately 20 bp (Fig 3b, lanes 7–12). These products were not observed from reverse transcriptase–PCR reactions using mRNA from nonmelanocytic cells (see Fig 4) or from preparations of MNT-1 mRNA in which the reverse transcriptase enzyme had not been included (Fig 3b, lanes 8, 11, and 14), illustrating the specificity of the signal. These products likely represent the amplified products of the two previously described alternatively spliced mRNA: a less abundant long form, originally cloned and described as Pmel17 (Kwon et al, 1991), and a more abundant form, originally cloned and described as gp100 or ME20, lacking 21 bp encoding seven amino acids (Adema et al, 1994; Maresh et al, 1994) (see Fig 5c). We refer to these two products as Pmel17-l and Pmel17-i for long and intermediate forms, respectively. Even though our reverse transcriptase–PCR reactions were not performed quantitatively, the relative abundance of these forms among our reverse transcriptase–PCR products from MNT-1 mRNA mirrors that previously described in other melanocytic cells in which Pmel17-i is approximately 5-fold more abundant than Pmel17-l (Bailin et al, 1996; Fig 3b, lanes 7–12). The difference in predicted molecular mass of Pmel17-l and Pmel17-i is less than 700 Da, and is unlikely to be responsible for the ≈5000 Da difference between the unprocessed full-length Pmel17 (P1 form) and Pmel17-s observed in immunoprecipitates. Thus, the difference between Pmel17-s and the longer forms is unlikely due to splice differences in the 3′ half of the Pmel17 coding region.

Figure 3. Detection of Pmel17 mRNA with an internal deletion by reverse transcriptase–PCR of mRNA from MNT-1 cells.

(a) Schematic diagram of Pmel17 cDNA and position of primers used in this analysis. The noncoding 5′ - and 3′ -untranslated regions (5′ UT and 3′ UT) are indicated as solid lines, and the coding region is boxed and divided according to the domain structure of the encoded protein. Indicated are the regions encoding the signal peptide; the lumenal domain PKD homology domain, tandem repeat domain, cleavage site separating the Mα and Mβ fragment (CS), and the peptide excised in Pmel17-i; and the transmembrane (TM) and cytoplasmic (Cyt.) domains. The length of our Pmel17-l cDNA is indicated by nucleotide positions 1 and 2177. Bottom, the position of the primers, noted in Table I, within the cDNA is indicated, with arrows showing the direction of the primer. Not shown is primer 172, which is the reverse complement of 171. (b) Reverse transcriptase–PCR reactions from MNT-1 mRNA. MNT-1 mRNA was reverse transcribed using primer no. 398 (lanes 1, 4, 10, and 13) or no. 356 (lane 7); a parallel sample was incubated under identical conditions in the absence of reverse transcriptase enzyme (lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, and 14). Reaction products or 100 ng of purified Pmel17-l plasmid (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15) were subject to 30 cycles of PCR using the indicated forward primers and either no. 356 (lanes 7–9) or no. 398 (all other lanes) as the reverse primer. M, 100 bp markers; arrowhead indicates the 600 bp marker band. Predicted sizes for each of the reaction products for Pmel17-l are 1669, 1265, 524, 444, and 182 bp, respectively.

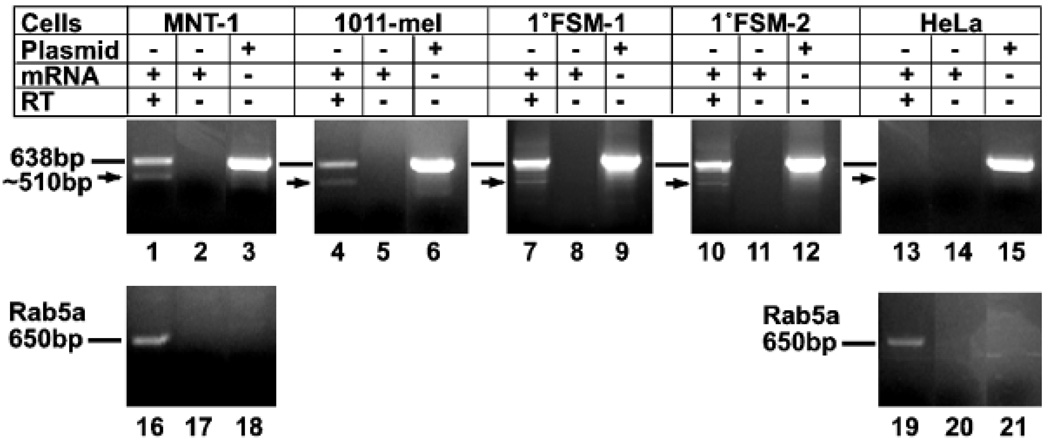

Figure 4. Broad expression of small Pmel17 mRNA in melanocytic cells by reverse transcriptase–PCR.

mRNA isolated from the melanoma cell lines MNT-1 (lanes 1–3 and 16–18) or 1011-mel (lanes 4–6), from two different primary foreskin melanocyte cultures (1° FSM-1, lanes 7–9; 1° FSM-2, lanes 10–12), or from nonmelanocytic HeLa cells (lanes 13–15 and 19–21) was reverse transcribed using primer no. 172; parallel reactions were performed identically but with no added reverse transcriptase enzyme (lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, and 20). The products of these reactions or 100 ng of plasmid encoding Pmel17-l (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15) were subjected to 30 cycles of PCR using primers no. 172 and no. 145 to amplify a region that would best distinguish the short and long forms of Pmel17 (lanes 1–15). The 638 bp reaction product, predicted from the sequence of Pmel17-l, is indicated by a line, and the 510 bp reaction product corresponding to the short form is indicated by an arrow. As a positive control, a 650 bp cDNA fragment for Rab5a was amplified using primers no. 319 and no. 321 from RNA isolated from MNT-1 (lanes 16 and 17) and HeLa cells (lanes 19 and 20); the same reaction was also performed on Pmel17-l plasmid (lanes 18 and 21).

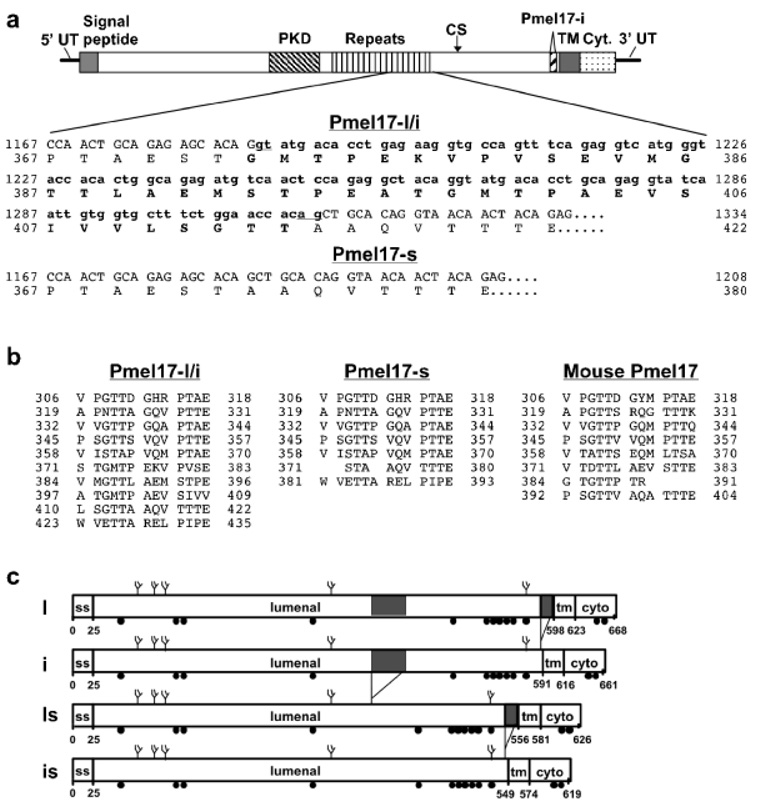

Figure 5. Sequence analysis of cDNA corresponding to the small Pmel17 mRNA reveals a deletion of part of the internal repeats.

(a) Comparison of the sequence of the small and large Pmel17 mRNA. Shown at top is a schematic of the Pmel17-l cDNA (see Fig 3a for explanation). The indicated region of Pmel17-l and Pmel17-i is expanded below to show the nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence. The region in bold type is absent from the cDNA isolated for the short form; the nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence of this region of the short form is indicated at the bottom. Numbers correspond to the nucleotide position of our Pmel17-l cDNA clone and the amino acid positions of the mature protein (with signal peptide removed). (b) Comparison of the direct repeat region in Pmel17-l/PMEL17-i with that predicted from the nucleotide sequence of Pmel17-s. The alternative splice removes 3.5 of the 10 imperfect direct repeats. Numbers correspond to the amino acid positions of the mature protein (with signal peptide removed). (c) Schematic diagram of four Pmel17 mRNA for which the cDNA were isolated from MNT-1 cells. Lumenal, transmembrane (tm) and cytoplasmic (cyto) domains are indicated. Spliced regions are indicated by gray shading.

By contrast, when reverse transcriptase–PCR reactions were performed using primer sets that spanned a longer region encompassing more 5′ coding regions of full-length Pmel17, two bands differing by ≈ 130 bp were observed (Fig 3b, lanes 1–6; due to the large size of these products, the 21 bp difference between Pmel17-l and Pmel17-i would not be expected to be resolved). The smaller of these products was less abundant than the larger, representing on average approximately 10% of the total signal. Its size and abundance is consistent with the potential that this band was derived from the mRNA encoding Pmel17-s. Consistently, the same doublet was observed in reverse transcriptase–PCR products from two primary melanocyte cultures and an additional melanoma cell line, whereas neither product was observed from reverse transcriptase–PCR reactions using RNA from nonmelanocytic HeLa cells or from reactions using melanocytic cell mRNA but lacking reverse transcriptase enzyme (Fig 4). Furthermore, reverse transcriptase–PCR reactions using comparable primers for mouse Pmel17 and mRNA from the mouse melanocytic cell line, melan-a, yielded only a single band corresponding to the expected size of full-length mouse Pmel17 (data not shown), consistent with the failure to detect a Pmel17-s isoform by immunoprecipitation in these cells.

In order to define better the nature of this alternative form of Pmel17, products from reverse transcriptase–PCR reactions from MNT-1 cells were fractionated, excised, subcloned into plasmid vectors, and sequenced. Concordant results from three independent clones derived from two separate reverse transcriptase–PCR reactions using different primer sets revealed that the smaller product lacked 126 bp derived from the middle of the Pmel17 mRNA (nucleotides 1118–1243 of the coding region; Fig 5a). This sequence, encoding more than three of the direct repeats within the Pmel17 lumenal domain (Fig 5b), is encompassed within exon 6 of the Pmel17 gene. The deleted region begins with a “gt” dinucleotide and ends with an “ag” dinucleotide (Fig 5a) but lacks other consensus sites for intron recognition, suggesting that it may represent an infrequently excised, cryptic intron within exon 6. The polypeptide region predicted by the translation of this region (Fig 5a, bold type) would have a mass of 4235 Da, consistent with the reduction in relative molecular mass by SDS–PAGE of Pmel17-s compared with full-length Pmel17 (Fig 1 and Fig 2). Among the isolated cDNA clones that lacked this 126 bp region, some contained and others lacked the 21 bp region that distinguishes Pmel17-l from Pmel17-i; thus, the two alternative splicing reactions can occur independently and can result in four different Pmel17 mRNA products (Fig 5c).

Pmel17-s is processed and localized similarly to full-length Pmel17

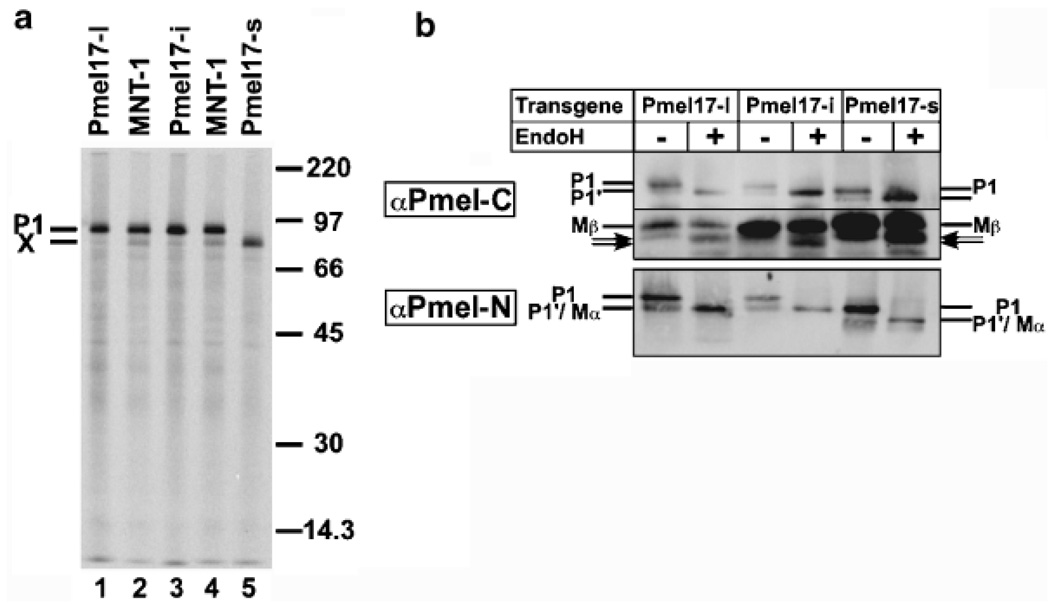

To confirm that the truncated mRNA encodes Pmel17-s and to compare its biosynthetic characteristics with that of other Pmel17 isoforms, we constructed mammalian expression vectors encoding full-length Pmel17-s, Pmel17-i, and Pmel17-l and expressed the encoded products by transfection in non-melanocytic HeLa cells. As shown in Fig 6(a), the product of the putative Pmel17-s cDNA immunoprecipitated from cell lysates of metabolically pulse-labeled, transfected HeLa cells (lane 5) comigrated with Pmel17-s from immunoprecipitates of MNT-1 cells (lane 4). By contrast, Pmel17-l and Pmel17-i from lysates of pulse-labeled transfected HeLa cells both comigrated with the P1 form observed in MNT-1 cells (compare lanes 1 and 3 with lane 2). Taken together with the data shown in Fig 2, this confirms that Pmel17-s is the product of the alternatively spliced, truncated Pmel17 mRNA.

Figure 6. Expression and processing of Pmel17-s in HeLa cells.

(a) Immunoprecipitation of three Pmel17 isoforms from metabolically pulse labeled HeLa cells. MNT-1 cells (lanes 2 and 4) or HeLa cells transiently transfected with expression vectors for Pmel17-l (lane 1), Pmel17-i (lane 3), or Pmel17-s (ls form; see Fig. 5c lane 5) were labeled for 15 min with 35S-methionine/cysteine. Triton X-100 cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with αPmel-C, fractionated by SDS–PAGE, and analyzed by phosphorimaging. Position of molecular weight markers is indicated to the right, and the positions of the P1 and band X forms of Pmel17 in MNT-1 cells is indicated to the left. (b) Western blot analysis of Pmel17 isoforms expressed in HeLa cells. Whole cell lysates of transiently transfected HeLa cells expressing Pmel17-l, Pmel17-i or Pmel17-s were treated or not with EndoH, fractionated by SDS–PAGE on 12% (upper panel) or 8% (lower panel) polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose using 15% (upper panel) or 2% (lower panel) methanol, and immunoblotted with antibodies to the cytoplasmic domain (Pmel-C, upper panel) or the lumenal domain (Pmel-N, lower panel). Relevant portions of the gels encompassing the P1, Mβ, and Mα isoforms, and of EndoH-digested P1 (P1’), as indicated, are shown; no other specific bands were reproducibly observed. Variation in band intensity is due to different transfection efficiencies, which varied from experiment to experiment.

Pmel17 is cleaved in a post-Golgi compartment to Mα and Mβ fragments (Berson et al, 2001). To determine whether the internal deletion within Pmel17-s affected the processing of Pmel17 to these fragments, we analyzed transfected HeLa cells by western blotting using antibodies that detect either fragment; whole cell lysates were untreated or treated with EndoH to distinguish coreglycosylated, EndoH-sensitive, pre-Golgi localized isoforms from fully processed, EndoH-resistant, post-Golgi forms. Using αPmel-C to the cytoplasmic domain, a mostly EndoH-resistant Mβ band, in addition to the full-length EndoH-sensitive P1 precursor, was found to accumulate in cells transfected with all three Pmel17 isoforms (Fig 6b, top panel; in data not shown, the migration of EndoH-treated P1 was similar to that of P1 treated with protein N-glycanase F, indicating that all N-linked glycans were susceptible to EndoH digestion). Consistent with previous results (Kobayashi et al, 1994; Berson et al, 2001), the transient P2 form does not accumulate, whereas the slow exit of Pmel17 from the endoplasmic reticulum is responsible for the accumulation of P1. Whereas the P1 band for Pmel17-s differed in migration from that for Pmel17-l and Pmel17-i, the Mβ band from each migrated identically, consistent with the splice variation occurring within the Mα coding region. Using the αPmel-N antibody to the lumenal domain, a stable EndoH-resistant Mα fragment was found to accumulate in cells expressing each of the three isoforms (note the collapse of EndoH-digested P1 into comigrating EndoH-resistant Mα; Fig 6b, bottom panel). As expected, the Pmel17-s-derived Mα fragment migrated faster than the Pmel17-l- and Pmel17-i-derived Mα fragment. Metabolic pulse/chase and immunoprecipitation analyses also showed similar processing patterns for all three Pmel17 isoforms (data not shown). Thus, alternative splicing does not appear to affect the biosynthetic processing of Pmel17.

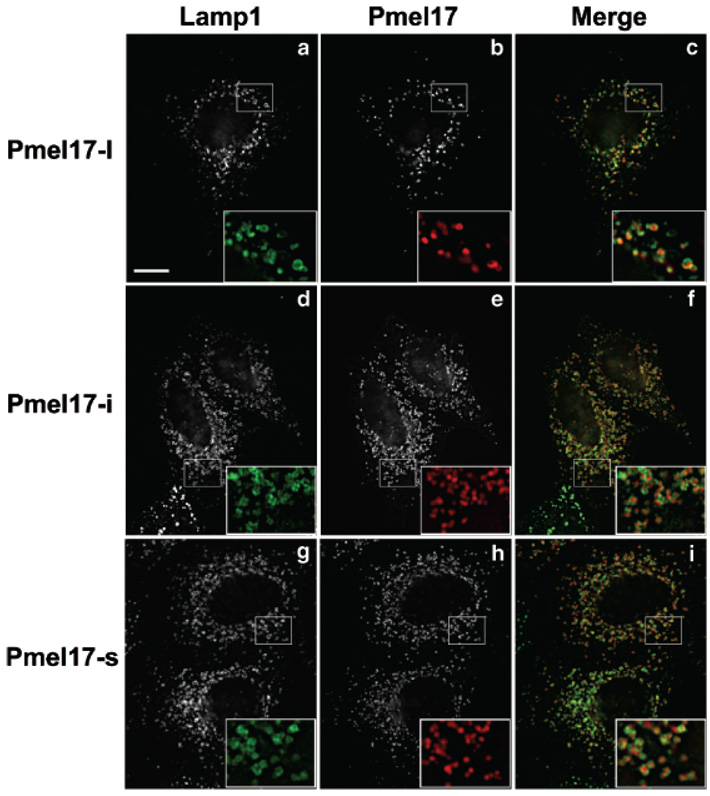

When expressed ectopically in nonpigment cells, Pmel17-l localizes to the intralumenal vesicles of late endosomal multivesicular structures and to fibers that form de novo upon Pmel17-l expression (Berson et al, 2001). To determine whether alternative splicing affects localization, transfected HeLa cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy for the localization of each of the Pmel17 isoforms. As shown in Fig 7, all three isoforms display a similar steady-state localization to vesicular compartments throughout the cytoplasm, as was shown for Pmel17-l. In all three cases, these vesicles overlapped with a subset of Lamp1-containing compartments, and thus correspond to late endosomes or lysosomes; in cells with very high expression, these Lamp1-positive structures were enlarged, and the Lamp1 staining could be observed surrounding the Pmel17 staining (Fig 7c,f,i, insets). Thus, all three isoforms localize similarly in nonpigment cells. We interpret the staining pattern to represent the accumulation of Pmel17 in intralumenal vesicles of late endosomes and/or lysosomes, in which Lamp1 accumulates on the limiting membrane (Berson et al, 2001). Given the correspondence of localization to late endosomes in HeLa cells and to melanosome precursors in pigment cells, it is likely that all three isoforms localize similarly in melanocytes as well.

Figure 7. Immunofluorescence microscopy analyses of the localization of Pmel17-l, Pmel17-i, and Pmel17-s expressed in HeLa cells.

Transiently transfected HeLa cells expressing Pmel17-l (a–c), Pmel17-i (d–f), or Pmel17-s (g–i) were fixed and stained with antibodies HMB50 (IgG2a, to Pmel17) and H4A3 (IgG1, to Lamp1) and isotype-specific, fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (fluorescein isothiocyanate, anti-γ1; Texas Red, anti-γ2a). Cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM), and stacks of images in multiple z focal planes were deconvolved using OpenLab software. Shown are individual fields for Lamp1 (a,d,g), Pmel17 (b,e,h), and colorized, merged images (c,f,i). The boxed region in each panel is magnified × 2.5 at the bottom right of each panel to emphasize the degree of colocalization. Bar: (a) 10 µm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified a novel splice variant of human Pmel17/gp100, an important constituent of early stage melanosomes and a common target for tumor-directed T lymphocytes in melanoma patients. The expression of this variant by normal and transformed melanocytes has interesting implications for the function of Pmel17 in melanocytes and for the generation of T cell epitopes by melanoma cells.

Band X represents the novel Pmel17 splice variant, Pmel17-s

In our previous characterization of Pmel17 in human melanocytic cells (Berson et al, 2001), we showed that a large Mα fragment is generated as a result of post-Golgi proteolytic processing of Pmel17. Characterization of Mα, however, was clouded by the presence of a comigrating band, “band X”, that was immunoprecipitated from metabolically pulse-labeled cells using anti-Pmel17 antibodies; as Mα and its cognate proteolytic fragment, Mβ, appear only after a chase period, it was difficult to reconcile the appearance of the Mα-like band X prior to Golgi processing. We now clearly identify band X as Pmel17-s, the product of an alternatively spliced Pmel17 mRNA. Because it lacks part of the central region of the lumenal domain of Pmel17, Pmel17-s is directly immunoprecipitable with antibodies to both the N- and C-termini of Pmel17, as well as with additional antibodies to the lumenal domain (Fig 2). It is distinguished from Mα based on this immunoreactivity (Mα is not reactive with antibodies to the C-terminus), on its appearance in pulse-labeled cells, and on its sensitivity to EndoH (Fig 1 and Fig 2) (Berson et al, 2001). A band with similarity to Pmel17-s has been previously observed by other groups (e.g., see Vogel and Esclamado, 1988; Adema et al, 1996).

Pmel17-s is generated in melanoma cells and in primary melanocytes (Fig 1 and Fig 4), although the relative proportion of Pmel17-s among all Pmel17 products varies from cell to cell and in some cases from experiment to experiment. Although it results from removal of an exonic sequence present in full-length Pmel17 mRNA, Pmel17-s is not consistently generated in HeLa cells transfected with expression vectors for Pmel17-l and Pmel17-i; this was apparent in an earlier study (Berson et al, 2001) and allowed us to clearly identify Mα in transfected cells. It does appear to be generated at low levels in Pmel17-l and Pmel17-i transfected HeLa cells in some experiments (e.g., see Fig 6a), suggesting that regulation of the alternative splice may be dependent on cell culture conditions, growth phase of the cells, or expression level. As the Pmel17-s splice was identified both in cDNA that contained and lacked the 21 bp alternative transcript that distinguishes Pmel17-l from Pmel17-i, the two alternative splice reactions must be independently regulated. Thus, human pigment cells can produce at least four distinct Pmel17 gene products by alternative splicing of a single precursor mRNA (Fig 5c).

Although mRNA for Pmel17-s was detected by reverse transcriptase–PCR in all human melanocytic cells tested (Fig 4), no comparable product was identified in mouse melanocyte cell lines. This is consistent with the failure to detect a comparable product by immunoprecipitation of metabolically pulse-labeled cells (our unpublished results and Kobayashi et al, 1994). Interestingly, although the mouse and human products share considerable homology at both the nucleotide (83%) and amino acid (75%) level, the region surrounding this alternatively spliced region varies significantly in sequence between the two species. This may explain the absence of the Pmel17-s product in the mouse. Given that the mouse Pmel17 gene does not encode the 21 bp insertion found in Pmel17-l (Martínez-Esparza et al, 1999), humans have evolved considerable variability in the production of Pmel17 isoforms relative to mice.

Pmel17-s and the significance of the repeat region

It is intriguing that Pmel17-s lacks several of the characteristic repeats present within the lumenal domain of Pmel17-l and Pmel17-i (Fig 5). This repeat region, first noted by Kwon et al (1991), consists of 10 tandem, imperfect repeats of a 13 amino acid sequence rich in glutamine, threonine, glycine, proline, and acidic residues. Our data indicate that the reduction in the number of the repeats has little effect on the post-Golgi processing or ultimate localization of Pmel17 products expressed ectopically in HeLa cells (Fig 6 and Fig 7). We speculate that the repeats may have some other function, such as binding to melanin intermediates (Donatien and Orlow, 1995; Chakraborty et al, 1996; Lee et al, 1996), oligomerization, or fibril formation (Berson et al, 2001, 2003). In support of the latter possibility, the amino acid content of the Pmel17 repeats is similar to that of a repeat region within a prion-like protein, Sup35p, in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae; these repeats have been shown to be required for the fibril forming activity of Sup35p (Parham et al, 2001). We are currently assessing the relative ability of Pmel17 isoforms to induce fibril formation upon expression in nonpigment HeLa cells; preliminary results suggest that the differences are likely to be subtle.

On the other hand, the repeat region of the chicken Pmel17 orthologue, MMP115 (Mochii et al, 1991), differs substantially in sequence and general amino acid content from that of mammalian orthologues, perhaps suggesting a role in specific interactions with distinct melanin intermediates. Interestingly, whereas there are 10 direct repeats in full-length human Pmel17 and its bovine orthologue, RPE1 (Kim and Wistow, 1992), the mouse (Kwon et al, 1995; Martínez-Esparza et al, 1999) and horse (Rieder et al, 2000) orthologues, like Pmel17-s, contain only seven. The difference in repeat number between mouse and human correlates with a distinction in the ability to detect post-Golgi processed forms of Pmel17 within melanocytes—these forms are difficult to detect in the mouse (e.g., see Kobayashi et al, 1994), yet readily detectable in human melanocytic cells (this study and Berson et al, 2001). Perhaps the repeats regulate the kinetics of interactions of Pmel17 with melanins that ultimately mask Pmel17 antibody epitopes (Donatien and Orlow, 1995). Nmb (Weterman et al, 1995) and its orthologues QNR71 (Turque et al, 1996) and osteoactivin (Safadi et al, 2001) are close homologs of Pmel17 but lack any repeat region; comparison of the activities of these proteins with those of the various isoforms of Pmel17 should elucidate a role for the direct repeats.

Splice variation and anti-melanoma immunity

The existence of a distinct isoform of human Pmel17 has potential relevance for anti-tumor immunity. Pmel17—better known to tumor immunologists as gp100—is a major endogenous and experimental target for melanoma-reactive T lymphocytes; numerous Pmel17-derived epitopes have been found to bind to HLA class I and class II molecules and serve as targets for both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively (Kawakami et al, 2000; Overwijk and Restifo, 2000; Slingluff et al, 2000). The most broadly recognized T cell epitopes cluster either in the amino-terminal region of the lumenal domain or downstream of the repeat region (Kawakami et al, 1998b; Castelli et al, 1999; Bullock et al, 2000; Cochlovius et al, 2000; Touloukian et al, 2000; Kierstead et al, 2001; Kobayashi et al, 2001). Nevertheless, the region that is deleted from Pmel17-s spans two consensus binding epitopes for HLA-DR molecules, including one with very high affinity for both HLA-DRB1 *0404 and DRB1*0401 (Kierstead et al, 2001), and another with broad HLA-DR binding activity (Cochlovius et al, 2000). The latter epitope was capable of eliciting a T cell proliferative response from several healthy donors (Cochlovius et al, 2000). Thus, altered expression of Pmel17 isoforms may affect T cell immune responses. Furthermore, the novel peptide sequence generated by Pmel17-s could potentially encompass a neorecognition element for certain HLA-DR molecules. That such a neoepitope could exist is underscored by the finding that tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells derived from a melanoma patient recognized an HLA-A24-binding peptide derived from an intronic sequence (Robbins et al, 1997). The existence of such an epitope from Pmel17-s could potentially explain the reactivity of Pmel17-specific tumor-infiltrating T cells from a melanoma patient that were unable to recognize autologous antigen-presenting cells pulsed with peptides derived from the entire sequence of Pmel17-l and Pmel17-i (Robbins et al, 2002).

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Raposo and A. Theos for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, A. Yoshino for assistance with the reverse transcriptase–PCR reactions, and M. Herlyn and R. Finko for gifts of the primary melanocyte cultures. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants no. R01 EY012207 from the National Eye Institute and R01 AR048155 from the National Institute for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Abbreviations

- EndoH

endoglycosidase H.

REFERENCES

- Adema GJ, de Boer AJ, Vogel AM, Loenen WAM, Figdor CG. Molecular characterization of the melanocyte lineage-specific antigen gp100. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20126–20133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adema GJ, Bakker ABH, de Boer AJ, Hohenstein P, Figdor CG. Pmel17 is recognized by monoclonal antibodies NKI-beteb, HMB-45 and HMB-50 and by anti-melanoma CTL. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:1044–1048. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailin T, Lee ST, Spritz RA. Genomic organization and sequence of D12S53E (Pmel 17), the human homologue of the mouse silver (si) locus. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:24–27. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12326976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DC, Cooper PJ, Dexter TJ, Devlin LM, Heasman J, Nester B. Cloned mouse melanocyte lines carrying the germline mutations albino brown Complementation in culture. Development. 1989;105:379–385. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson JF, Frank DW, Calvo PA, Bieler BM, Marks MS. A common temperature-sensitive allelic form of human tyrosinase is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum at the nonpermissive temperature. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12281–12289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson JF, Harper D, Tenza D, Raposo G, Marks MS. Pmel17 initiates premelanosome morphogenesis within multivesicular bodies. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3451–3464. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson JF, Theos AC, Harper DC, Tenza D, Raposo G, Marks MS. Proprotein convertase cleavage liberates a fibrillogenic fragment of a resident glycoprotein to initiate melanosome biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:521–523. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock TN, Colella TA, Engelhard VH. The density of peptides displayed by dendritic cells affects immune responses to human tyrosinase and gp100 in HLA-A2 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2000;164:2354–2361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo PA, Frank DW, Bieler BM, Berson JF, Marks MS. A cytoplasmic sequence in human tyrosinase defines a second class of di-leucine-based sorting signals for late endosomal and lysosomal delivery. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12780–12789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli C, Tarsini P, Mazzocchi A, et al. Novel HLA-Cw8-restricted T cell epitopes derived from tyrosinase-related protein-2 and gp100 melanoma antigens. J Immunol. 1999;162:1739–1748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty AK, Platt JT, Kim KK, Kwon BS, Bennett DC, Pawelek JM. Polymerization of 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid to melanin by the Pmel 17/silver locus protein. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:180–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.t01-1-00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiamenti AM, Vella F, Bonetti F, et al. Anti-melanoma monoclonal antibody HMB-45 on enhanced chemiluminescence-western blotting recognizes a 30–35 kDa melanosome-associated sialated glycoprotein. Melanoma Res. 1996;6:291–298. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochlovius B, Stassar M, Christ O, Raddrizzani L, Hammer J, Mytilineos I, Zoller M. In vitro and in vivo induction of a Th cell response toward peptides of the melanoma-associated glycoprotein 100 protein selected by the TEPITOPE program. J Immunol. 2000;165:4731–4741. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donatien PD, Orlow SJ. Interaction of melanosomal proteins with melanin. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232:159–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing VJ. Biochemical control of melanogenesis and melanosomal organization. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:24–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsp.5640176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing VJ. The melanosome: The perfect model for cellular responses to the environment. Pigment Cell Res. 2000;13:23–34. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.13.s8.7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J, Ward CJ, Peral B, et al. The polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD1) gene encodes a novel protein with multiple cell recognition domains. Nature Genet. 1995;10:151–160. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Y, Robbins PF, Wang RF, Parkhurst M, Kang XQ, Rosenberg SA. The use of melanosomal proteins in the immunotherapy of melanoma. J Immunother. 1998a;21:237–246. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Y, Robbins PF, Wang X, et al. Identification of new melanoma epitopes on melanosomal proteins recognized by tumor infiltrating T lymphocytes restricted by HLA-A1-A2, and -A3 alleles. J Immunol. 1998b;161:6985–6992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Y, Suzuki Y, Shofuda T, et al. T cell immune responses against melanoma and melanocytes in cancer and autoimmunity. Pigment Cell Res. 2000;13:163–169. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.13.s8.29.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierstead LS, Ranieri E, Olson W, et al. gp100/Pmel17 and tyrosinase encode multiple epitopes recognized byTh1-type CD4 + T cells. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1738–1745. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim RY, Wistow GJ. The cDNA RPE1 and monoclonal antibody HMB-50 define gene products preferentially expressed in retinal pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res. 1992;55:657–662. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90170-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KK, Youn BS, Heng HH, et al. Genomic organization and FISH mapping of human Pmel17, the putative silver locus. Pigment Cell Res. 1996;9:42–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1996.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Lu J, Celis E. Identification of helper T-cell epitopes that encompass or lie proximal to cytotoxic T-cell epitopes in the gp100 melanoma tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7577–7584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Urabe K, Orlow SJ, et al. The Pmel17/silver locus protein. Characterization and investigation of its melanogenic function. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29198–29205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon BS, Halaban R, Kim GS, Usack L, Pomerantz S, Haq AK. A melanocyte-specific complementary DNA clone whose expression is inducible by melanotropin and isobutylmethyl xanthine. Mol Biol Med. 1987;4:339–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon BS, Chintamaneni C, Kozak CA, et al. A melanocyte-specific gene, Pmel17, maps near the silver coat color locus on mouse chromosome 10 and is in a syntenic region on human chromosome 12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9228–9232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon BS, Halaban R, Ponnazhagan S, Kim K, Chintamaneni C, Bennett D, Pickard RT. Mouse silver mutation is caused by a single base insertion in the putative cytoplasmic domain of Pmel17. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:154–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ZH, Hou L, Moellmann G, et al. Characterization and subcellular localization of human Pmel17/silver, a 100-kDa (pre) melanosomal membrane protein associated with 5,6,-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid (DHICA) converting activity. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:605–610. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12345163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maresh GA, Marken JS, Neubauer M, Aruffo A, Hellström I, Hellström KE, Marquardt H. Cloning and expression of the gene for the melanoma-associated ME20 antigen. DNA Cell Biol. 1994;13:87–95. doi: 10.1089/dna.1994.13.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MS, Seabra MC. The melanosome: Membrane dynamics in black and white. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:738–748. doi: 10.1038/35096009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Esparza M, Jiménez-Cervantes C, Bennett DC, Lozano JA, Solano F, García-Borrón JC. The mouse silver locus encodes a single transcript truncated by the silver mutation. Mammalian Genome. 1999;10:1168–1171. doi: 10.1007/s003359901184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochii M, Agata K, Eguchi G. Complete sequence and expression of a cDNA encoding a chicken 115-kDa melanosomal matrix protein. Pigment Cell Res. 1991;4:41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1991.tb00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlow SJ. Melanosomes are specialized members of the lysosomal lineage of organelles. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:3–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12312291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlow SJ, Zhou B-K, Boissy RE, Pifko-Hirst S. Identification of a mammalian melanosomal matrix glycoprotein. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:141–144. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12363626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overwijk WW, Restifo NP. Autoimmunity and the immunotherapy of cancer: Targeting the “self” to destroy the “other”. Crit Rev Immunol. 2000;20:433–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham SN, Resende CG, Tuite MF. Oligopeptide repeats in the yeast protein Sup35p stabilize intermolecular prion interactions. EMBO J. 2001;20:2111–2119. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quevedo WC, Fleischmann RD, Dyckman J. Premature loss of melanocytes from hair follicles of light (Blt) and silver (si) mice. In: Seiji M, editor. Phenotypic Expression in Pigment Cells. Tokyo: Tokyo University Press; 1981. pp. 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Tenza D, Murphy DM, Berson JF, Marks MS. Distinct protein sorting and localization to premelanosomes, melanosomes, and lysosomes in pigmented melanocytic cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:809–823. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder S, Stricker C, Joerg H, Dummer R, Stranzinger G. A comparative genetic approach for the investigation of ageing grey horse melanoma. J Anim Breed Genet. 2000;117:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins PF, El-Gamil M, Li YF, Fitzgerald EB, Kawakami Y, Rosenberg SA. The intronic region of an incompletely spliced gp100 gene transcript encodes an epitope recognized by melanoma-reactive tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:303–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins PF, El-Gamil M, Li YF, Zeng G, Dudley M, Rosenberg SA. Multiple HLA class II-restricted melanocyte differentiation antigens are recognized by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from a patient with melanoma. J Immunol. 2002;169:6036–6047. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehm NW, Marrack P, Kappler JW. Antigen-specific, H-2-restricted helper T cell hybridomas. J Exp Med. 1982;156:191–204. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.1.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safadi FF, Xu J, Smock SL, Rico MC, Owen TA, Popoff SN. Cloning and characterization of osteoactivin, a novel cDNA expressed in osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2001;84:12–26. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slingluff CL, Jr, Colella TA, Thompson L, et al. Melanomas with concordant loss of multiple melanocytic differentiation proteins Immune escape that may be overcome by targeting unique or undefined antigens. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2000;48:661–672. doi: 10.1007/s002620050015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanakis E, Lamina P, Bennett DC. Effects of the developmental colour mutations silver and recessive spotting on proliferation of diploid and immortal mouse melanocytes in culture. Development. 1992;114:675–680. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.3.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm RA, Teasdale RD, Box NF. Human pigmentation genes: Identification, structure and consequences of polymorphic variation. Gene. 2001;277:49–62. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touloukian CE, Leitner WW, Topalian SL, Li YF, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Identification of a MHC class II-restricted human gp100 epitope using DR4-IE transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2000;164:3535–3542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turque N, Denhez F, Martin P, et al. Characterization of a new melanocyte-specific gene (QNR-71) expressed in v-myc-transformed quail neuroretina. EMBO J. 1996;15:3338–3350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel AM, Esclamado RM. Identification of a secreted Mr 95,000 glycoprotein in human melanocytes and melanomas by a melanocyte specific monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1988;48:1286–1294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weterman MA, Ajubi N, van Dinter IM, Degen WG, van Muijen GN, Ruitter DJ, Bloemers HP. nmb, a novel gene, is expressed in low-metastatic human melanoma cell lines and xenografts. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:73–81. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]