Abstract

Inhibiting angiogenesis has become an effective approach for treating cancer and other diseases. However, our understanding of signaling pathways in tumor angiogenesis has been limited by the embryonic lethality of many gene knockouts. To overcome this limitation, we used the plasticity of embryonic stem (ES) cells to develop a unique approach to study tumor angiogenesis. Murine ES cells can be readily manipulated genetically; in addition, ES cells implanted subcutaneously in mice develop into tumors that contain a variety of cell types (teratomas). We show that ES cells differentiate into bona fide endothelial cells within the teratoma, and that these ES-derived endothelial cells form part of the functional tumor vasculature. Using this powerful and flexible system, the Angiopoietin/Tie2 system is shown to have a key role in the regulation of tumor vessel size. Endothelial differentiation in the ES teratoma model allows gene-targeting methods to be used in the study of tumor angiogenesis.

Keywords: teratoma, endothelial cells, VEGF-R2, VE-PTP

Despite many attempts to target the process of vessel growth (angiogenesis) in diseases such as cancer and age-related macular degeneration, only therapies targeting the VEGF pathway have been approved to date (1, 2). However, previous studies have shown that angiogenesis depends on the coordinated interplay of many growth factors and receptor systems that may also be targeted for clinical benefit, although the role of these potential targets in disease modes needs to be better defined. In recent years, one of the first steps in assessing the role of a particular protein in angiogenesis has been to delete a single copy of the corresponding gene in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells, and then, using conventional breeding approaches, to analyze the effects of double-copy gene deletion on murine embryonic development (3). Such studies can provide important insights into the function of a gene in developmental angiogenesis. For example, deletion of VEGF or its receptor VEGF-R2 (FLK1, or KDR) results in dramatic inhibition of the early stages of angiogenesis (4–6). In comparison, deletion of Tie2 receptor, its ligands angiopoietin-1 or -2 (Ang1, Ang2), or the vascular endothelial receptor tyrosine phosphatase VE-PTP (PTPRB), results in defects in the later stages of vessel remodeling (7–10), after the formation of the primitive vasculature. Perhaps not surprisingly, deletion of many of these genes usually results in vascular or cardiac defects that lead to embryonic lethality at mid-gestation, which precludes assessment of the role of the protein in disease processes, such as tumor angiogenesis. Although conditional gene targeting approaches can allow further study of angiogenesis genes, these approaches require intense and prolonged effort to develop and validate the systems. Alternatively, pharmacologic approaches can also shed light on the role of particular pathways in pathologic angiogenesis; however, again, prolonged efforts are usually necessary to develop potent reagents to specifically inhibit a signaling pathway in vivo. Therefore, additional systems in which angiogenic pathways can be selectively targeted in disease models are needed.

In this study, we made use of the plasticity of mouse ES cells, and the ability to genetically manipulate these cells (11–15), to evaluate the effects of several gene deletions on tumor angiogenesis. ES cells implanted s.c. in mice develop into tumors that contain various cell types (teratomas). We found that bona fide endothelial cells are among the cell types that form within ES cell teratomas (16), and furthermore, that these ES cell-derived endothelial cells connect with host-derived endothelial cells to form the functional tumor vasculature. ES cells were manipulated to express a reporter gene (β-galactosidase) in the place of several endothelial cell-specific genes. When grown as teratomas, these cells were readily revealed in vascular structures by immunostaining and could been analyzed from the tumors by FACS.

Using this powerful and flexible system, genetic deletion of both alleles (knock-out or KO) of endothelial cell-specific genes such as VEGF-R2 and VE-PTP in the ES cell tumors did not radically affect overall tumor growth because of compensation from the host vasculature, but instead produced distinct phenotypic abnormalities in the ES-derived tumor blood vessels. As expected, ES cells null for VEGF-R2 produced dramatically fewer vascular structures. On the other hand, ES cells null for VE-PTP differentiated into tumor vessels, but these vessels were significantly larger in diameter than control vessels and had increased Tie2 signaling. This study demonstrates that the gene-targeted ES tumor angiogenesis system can provide a powerful tool to analyze the role of specific signaling pathways in tumor angiogenesis.

Results

ES Cells in Teratomas Differentiate to Express Endothelial Cell-Specific Reporters.

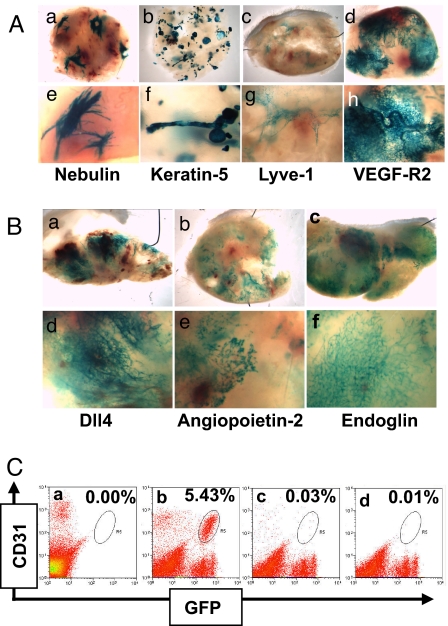

Previous studies have shown that murine ES cells implanted s.c. grow into tumors (teratomas) with a variety of differentiated cell types, including epithelial cells and neural cells (11, 12, 17). To analyze the process of cell differentiation in teratomas, we generated genetically modified ES cells in which cDNA encoding the β-galactosidase (β-gal) reporter gene was introduced, by homologous recombination, into the locus of cell type-specific genes (18). ES cells, in which a single copy of cell-specific genes such as Nebulin (striated muscle), Keratin-5 (complex epithelium), Lyve-1 (lymphatic endothelial cells), or VEGF-R2 (blood vessel endothelial cells) was replaced with β-gal, were implanted s.c. into mice and grown as teratomas. The resultant whole-mount LacZ staining patterns in each of these teratomas revealed distinct structures (Fig. 1A), corresponding to the distinct staining patterns seen in developing embryos or adults generated from these ES cells (18). The muscle-specific reporter gene, nebulin, shows clusters of elongated cells (corresponding to skeletal muscle) distributed in several regions of the teratoma (see Fig. 1A-a and A-e). The epithelial cell reporter gene, keratin-5, shows numerous compact tubular and glandular-like structures (see Fig. 1A-b and A-f) (corresponding to epithelial structures), while the lymphatic endothelial marker, LYVE-1, shows occasional wispy connected structures (Fig. 1A-c and A-g) (corresponding to lymphatic vessels).

Fig. 1.

ES cell-derived blood vessel networks in teratomas. (A) Whole-mount LacZ staining seen at low and high magnification (Upper and Lower, respectively) of teratomas grown from ES cells in which the β-galactosidase gene was introduced into the locus of cell-type specific genes, including Nebulin (muscle cell specific, a and e), Keratin-5 (complex epithelial cells, b and f), Lyve-1 (lymphatic endothelial and other cells, c and g), and VEGF-R2 (vascular endothelial cells, d and h). (B) Whole-mount LacZ staining seen at low and high magnification (Upper and Lower, respectively) of teratomas grown from ES cells in which the β-galactosidase gene was introduced into other endothelial cell-specific genes Dll4 (a and d), angiopoietin-2 (b and e), and endoglin (c and f). (C) FACS analysis of teratomas derived from either WT or Rosa-eGFP ES cells. Cells expressing both CD31/Pecam and eGFP were detected in Rosa-eGFP tumors (b, circled) (5.43% of the total cell population), whereas no such population was detected in WT tumors (a) or in Rosa-eGFP tumors stained with isotype control antibody (c) or no antibody (d).

Significantly, in our studies, the whole-mount LacZ staining pattern from ES tumors of the vascular endothelial cell-specific gene VEGFR2+/β-gal showed extensive vessel-like networks throughout the tumor volume (see Fig. 1A-d and A-h), which was distinct from the pattern generated by nonvascular genes. Moreover, a similar vessel-like pattern was observed in ES cell tumors grown from a variety of vascular-specific genes targeted with β-gal, including Delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) (Fig. 1B-a and B-d), angiopoietin-2 (Fig. 1B-b and B-e), endoglin (Fig. 1B-c and B-f), Tie1, CD31/Pecam, and VE-PTP (see below), all of which produce vascular-specific staining in embryos derived from these ES cells. Thus, a subset of ES cells within a teratoma can express endothelial cell-specific marker genes and form vascular-like networks.

ES-Derived Endothelial Cells Comprise a Significant Fraction of the Tumor Vasculature.

To further verify that ES cells differentiate into endothelial cells in teratomas, and to quantify the relative numbers of these cells, we used FACS analysis to separate the different endothelial cell populations from the ES cell tumor. ES cells in which a cDNA encoding a florescent protein (eGFP) was knocked-in to the ubiquitously-expressed ROSA locus (ROSA-GFP), were implanted s.c. into mice, and allowed to grow as tumors. The tumors contained distinct populations of endothelial cells that were host derived (CD31+, an endothelial cell marker/GFP−, Upper Left quadrant) and ES cell-derived (CD31+/GFP+, Upper Right quadrant) (Fig. 1C-b), further demonstrating the presence of ES cell-derived endothelial cells in these tumors. In our ES tumors, approximately one-half of the total endothelial cells (CD31+) were found to come from the ES cells [average (mean) = 46%, range 26% to 66%, n = 17 tumors]. The conversion of tumor cells to functional endothelial cells may be unique to ES cell teratomas, as we did not detect any tumor-derived CD31+ cells in other tumor types, such as C6 gliomas or HT1080 sarcomas.

As a further characterization of ES cell-derived endothelial cells, we extracted total RNA from both the GFP+ and GFP− endothelial FACS populations (ES cell-derived and host-derived cells, respectively) (see Fig. 1C), as well as the CD31−, nonendothelial cell population, and compared the gene-expression profiles of these cell populations by microarray analysis. Many endothelial cell-specific genes, including CD31/Pecam, ICAM2, VEGF-R2, Tie1, VE-PTP, and Dll4, were differentially expressed to equivalent levels in the host-derived and ES cell-derived endothelial cells (Table S1), relative to control cells (Pearson correlation = 0.89). Thus, the tumor endothelial cells derived from the ES cells comprise approximately half of the tumor vasculature and were very similar or identical to the host-derived ES cells in terms of their gene-expression profile.

ES-Derived Blood Vessels Are Connected to the Host-Derived Vessels and Are Functional.

Further immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that ES cell tumors contain both ES-derived and host-derived networks of blood vessels. In this system, staining for CD31/Pecam marks all vessels (both host-derived and ES cell-derived), whereas staining for β-gal marks only the ES cell-derived vessels. The overall appearance of the vasculature in the teratomas (CD31 staining) (Fig. 2A-a) is similar to that seen in other rapidly growing murine s.c. tumor models; regions of the tumor appear to be well-vascularized, whereas other regions appear to be poorly vascularized and are flanked by sprouting neovessels. However, comparing adjacent sections from a VEGF-R2+/β-gal teratoma shows that the total tumor vasculature (CD31 staining) (see Fig. 2A-a) is comprised of regions that are derived from the ES cells (β-gal staining) (see Fig. 2A-b), as well as regions from the host (β-gal− regions) (see Fig. 2A-b). Note that while the tumor vessels are derived from both the host and ES cells, vessels in the skin are only from the host (β-gal−) (see Fig. 2A-a vs. A-b). At higher magnification, a network of host-derived vessels (CD31+, β-gal−) (see Fig. 2A-d and A-g) show the same morphology as a network of fully ES cell-derived vessels (CD31+, β-gal+) (see Fig. 2A-c and A-f). In some cases, the interface between two networks of different origin can be observed (see Fig. 2A-e and A-h). The ES-cell derived vessels were morphologically indistinguishable from host-derived vessels.

Fig. 2.

Teratoma vasculature consists of both ES cell-derived and host-derived vessels. (A) Immunohistochemistry of teratomas in which the β-gal gene was targeted into VEGF-R2 locus. Adjacent sections of the tumor were immunostained for Pecam/CD31 (a) or β-gal (b). Areas of interest framed in (a) and (b) shown at higher magnification (magnification 10×) (c–h). (c–e) Pecam/CD31 staining; (f–h) adjacent sections stained for β-gal. (c and f) A network of vascular structures derived from the ES cells (immunostained for both Pecam and β-gal) is shown, whereas (d) and (g) show a network of vessels in the same tumor derived from the host (Pecam+ but β-gal−). (e and h) Boundary of host-derived vessels on the right hand side and ES-derived vessels on the left hand side. (B) Comparison of ES cell-derived blood vessels from VEGF-R2 het and VEGF-R2 null (KO) ES tumors. Whole-mount view of tumors from VEGF-R2 het (a) shows regions of LacZ staining (ES-derived vessels), whereas tumors from VEGF-R2 KO (b) have very few such regions. Area density (c) of LacZ staining from VEGF-R2 KO tumors is less than 10% of that from (control) VEGF-R2 het tumors.

We next assessed whether these ES cell-derived vessel networks in teratomas were functional; that is, whether they were perfused by systemically administered intravascular tracers. Tumor-bearing mice were injected intravenously with a lectin, and the tumors assessed for distribution of the lectin in relation to ES cell-derived vessel structures. Double fluorescence staining of lectin and β-gal (Fig. S1) showed that the β-gal-expressing structures were indeed perfused by lectin, indicating that ES-derived blood vessels are functional to support blood flow.

ES Cell-Derived Endothelial Cells Are Largely Dependent on VEGF-R2.

To further validate this system, we asked whether the ES-derived blood vessels are VEGF-R2 dependent. To this end, we deleted both alleles (KO) of VEGF-R2 (Kdr or Flk1), a critical gene for endothelial cell development (4). Unlike embryos that lack VEGF-R2, which die very early during embryogenesis, the VEGF-R2 KO teratomas grew at approximately the same rate as control teratomas because of compensation by the host vasculature. Analogous to the lack of vascular formation in the corresponding embryos, very few ES cell-derived blood vessels were found in VEGF-R2 KO tumors (Fig. 2B-a and B-b). Disorganized clusters of LacZ+ cells were found (see Fig. 2B-b), and the area extent of LacZ staining in the VEGF-R2 KO ES tumors was less than 10% of the area extent of VEGF-R2 het structures (Fig. 2B-c).

Exploiting ES Tumor Model to Explore VE-PTP in Tumor Angiogenesis.

Our findings that (i) a significant proportion of the functional vasculature in ES tumors is derived from the ES cells themselves, (ii) these cells can be marked by endothelial cell-specific reporter genes, and (iii) ES-derived and host-derived endothelial cells have very similar gene-expression profiles and responses to VEGF blockade, suggested that the function of vascular genes in tumor angiogenesis could be evaluated in this model.

VE-PTP, the only known endothelial-specific receptor tyrosine phosphatase with reported activity on Tie2 (19), has been shown to be necessary for embryonic development (9, 10) but has been difficult to otherwise manipulate in vivo. Unlike VE-PTP KO embryos that die embryonically during early vascular development, we found that VE-PTP KO teratomas grew at normal rates and formed extensive ES-derived endothelium. ES-derived blood vessels from VE-PTP het teratomas (CD31+, β-gal+) were morphologically indistinguishable from host-derived (CD31+, β-gal−) vessels (Fig. 3A-a and A-d). However, the ES-derived VE-PTP KO blood vessels (CD31+, β-gal+) (Fig. 3A-b, A-c, and A-e) were formed in a less hierarchical pattern and were typically larger in diameter than either the adjacent host-derived blood vessels (CD31+, β-gal−) (see Fig. 3A-b, A-e, and A-f) or ES-derived blood vessels in VEPTP-Het tumors (see Fig. 3A-a).

Fig. 3.

Deletion of VE-PTP results in tumor blood vessel enlargement. (A) Immunohistochemistry of teratomas in which the β-gal gene was targeted into either one (het) or both (KO) alleles of the VE-PTP locus. Tumor sections were immunostained for both β-gal (black-purple) and CD31/Pecam (brown). (a and d) Small-diameter vessels derived from VE-PTP het ES cells (low and high magnification views, 2.5× and 10×, respectively). (b) A low magnification view of vessels in a VE-PTP KO ES tumor, in which the black vessels (β-gal+) are derived from the ES cells and the brown vessels (Pecam+ only) are derived from the host. (c, e, and f). Enlarged views from (b), showing vessels of different origin. Note the enlarged diameter of the VE-PTP KO vessels (black) compared to the adjacent normal host vessels (brown). (B) Pharmacologic inhibition of angiopoietin-Tie signaling reduces tumor vessel diameter. Tumor sections from ES cells in which the β-gal gene was targeted into either one (het) or both (KO) alleles of the VE-PTP loci were immunostained for both β-gal (black-purple) and CD31/Pecam (brown). (magnification 10×) (a) Small-diameter vessels derived from VE-PTP het ES cells treated with control protein (hFc). (b) Enlarged vessels in a VE-PTP het ES cell tumor treated systemically with recombinant angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1). (c) Small diameter vessels in a VE-PTP het ES cell tumor treated systemically with an inhibitor of angiopoietins. (d) Large-diameter vessels derived from VE-PTP KO ES cells treated with control protein (hFc). (e) Further enlargement of the vessels in a VE-PTP KO ES cells tumor treated systemically with recombinant angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1). (f) Small-diameter vessels in a VE-PTP KO ES cell tumor treated systemically with an inhibitor of angiopoietins.

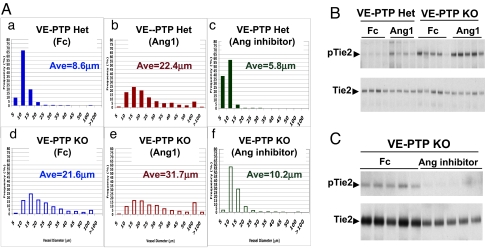

Measurement of vessel diameters from these tumors showed that VE-PTP KO vessels were on average ≈2.5-fold larger than VE-PTP het vessels (8.6 vs. 21.6 μm) (Fig. 4A-a, and A-d). The distribution of vessel diameters revealed that in control VE-PTP het tumors, about 99% of the ES-derived blood vessels were smaller than 20 μm in diameter, with 67% of the ES-derived blood vessels having a diameter of 5 to ≈10 μm. We confirmed that such a distribution was representative for tumor blood vessels in this system by determining that host-derived vessels from the same tumors show an almost identical size distribution. In contrast, in VE-PTP-null tumors, only 59% of ES-derived vessels were “normal” sized with diameters less than 20 μm, whereas 37% of these vessels were 20 to ≈50 μm in diameter, and 4% were larger than 50 μm in diameter (Fig. S2 and see Fig. 4A-d).

Fig. 4.

VE-PTP regulates angiopoietin-induced vessel diameter and Tie2 phosphorylation. (A) Distribution of blood vessel diameter (ES-derived blood vessels only) in VE-PTP het and VE-PTP KO tumors treated with control protein (hFc), recombinant angiopoietin-1, or angiopoietin inhhibitor. Tumor-bearing mice were systemically treated with hFc (a and d), angiopoietin-1 (b and e), or angiopoietin inhibitor (c and f). For each individual graph, the y axis shows frequency (percentage) of ES-derived vessels with diameter within a certain range as indicated on the x axis (vessel diameter bins, in micrometers). Mean values of vessel diameter from each group are also shown (Ave). The distributions are from 1,150 to 1,600 individual vessel measurements from four tumors per group (275–400 measurements per tumor). The averages shown in the panels are the means of the four individual mean diameters per group. (B) Western blot showing Tie2 phosphorylation following exogenous angiopoietin-1 treatment of teratomas. Mice bearing VE-PTP het and VE-PTP KO ES tumors were treated with either hFc or Ang1 for 4 h. Total tumor protein lysates were immunoprecipitated with Tie2 antibody and probed with either anti-Tie2 antibody or anti-phosphotyrosine antibody, as indicated. Each lane shows individual tumor (four to five tumors per group). Increased Tie2 phosphorylation was detected in VE-PTP KO ES tumors either with or without Ang1 treatment. (C) Western blot showing effect on Tie2 phosphorylation of pharmacologic inhibition of angiopoietins in teratomas. Mice bearing VE-PTP KO ES tumors were treated with hFc or angiopoietin inhibitor for 12 h. Total tumor protein lysates were immunoprecipitated with Tie2 antibody and probed with either anti-Tie2 antibody or anti-phosphotyrosine antibody as indicated. Tie2 phosphorylation was reduced in VE-PTP KO ES tumors treated with angiopoietin inhibitor. Equal amounts of total protein loaded in each lane. The amount of total Tie2 was somewhat reduced in the tumors treated with angiopoietin inhibitor, which may be because of a reduced overall vascularity in these tumors.

Treatment with Exogenous Tie2 Activators Can also Increase Tumor Vessel Diameter.

The vessel enlargement seen in VE-PTP-null vessels resembled previous findings that activation of the angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway also results in an increase in vessel diameter (20–23), although the effects of this pathway on vessel size have not yet been explored in tumor angiogenesis. To explore the role of the angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway, and possible regulation by VE-PTP, during tumor angiogenesis, we first asked whether manipulating the angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway could regulate blood vessel diameter in ES tumors. Therefore, teratoma-bearing mice were treated systemically with recombinant angiopoietin-1 protein (24), a reagent shown to activate Tie2 receptor tyrosine kinase in vivo through ligand-receptor interaction and to increase blood vessel diameter in certain settings (22).

As shown in Fig. 3B-a and B-b, treatment with Ang1 results in an increase in vessel diameter in both host-derived and ES-derived tumor blood vessels in VE-PTP het teratomas, agreeing with previous observation in other models. Interestingly, such an increase resembles the effect of VE-PTP KO (Fig. 3B-d). Furthermore, we observed a further vessel enlargement upon Ang1 treatment of VE-PTP null tumor vessels (Fig. 3B-e), such that these vessels were approximately fourfold larger in diameter than control tumor vessels.

Inhibition of Angiopoietins Reduces Tumor Vessel Enlargement Caused by VE-PTP Deletion.

To determine whether constitutive activation of the angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway was required for maintaining enlarged tumor vessels, we treated tumor-bearing mice systemically with a peptide-Fc fusion reagent described previously and known to specifically block interaction of angiopoietin-1 and -2 with Tie2 receptor (25, 26). ES cell-derived blood vessels in the VE-PTP KO tumors were dramatically reduced in diameter by inhibition of angiopoietins (Fig. 3B-d vs. B-f). The size distribution of VE-PTP-null tumor vessels was reversed to that of control tumor vessels (see Fig. 4A-f). Comparison of the abundance of various sized vessels revealed that blockage of angiopoietin-Tie2 interaction results in the disappearance of vessels larger than 20 μm in diameter in VE-PTP KO tumors (see Fig. S2), supporting the model that activation of the angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway by endogenous ligands is essential for the increased diameter of VE-PTP null vessels. We also observed a slight decrease in the diameter of control tumor vessels following blockade of angiopoietins, evidenced by an increase in the abundance of small diameter vessels (≈5 μm in diameter) (see Fig. S2).

Deletion of VE-PTP Results in Increased Tie2 Activation in Tumor Vessels.

We next asked whether VE-PTP is a negative regulator of Tie2 phosphorylation in vivo, based upon the above observations and the previous study of cultured endothelial cells (19). Comparison of the phosphorylation levels of Tie2 in VE-PTP het and null teratomas shows that the baseline (untreated) levels of Tie2 phosphorylation were significantly increased in VE-PTP-null tumors compared to control tumors (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, within 4 h after systemic Ang1 treatment, Tie2 phosphorylation levels were elevated about 2.5-fold in both control and VE-PTP-null tumors, such that in VE-PTP-null teratomas, the levels of Tie2 phosphorylation were more than sixfold higher compared to VE-PTP het counterparts (see Fig. 4B). Because of the presence of host-derived blood vessels in VE-PTP-null teratomas, which would dilute the ratio of phospho-Tie2 to total Tie2 as measured from total tumor extract, the fold increase of Tie2 phosphorylation in VE-PTP-null endothelial cells would be even higher.

Inhibition of Angiopoietins Reduces the Excess Tie2 Activation Caused by VE-PTP Deletion.

Finally, we asked whether the increased Tie2 phosphorylation levels seen in the VE-PTP-null tumors are a result of ligand-receptor interaction between angiopoietins and Tie2. Treatment with angiopoietin inhibitor decreased the levels Tie2 phosphorylation in the VE-PTP-null tumors down to those of control tumors (Fig. 4C), in agreement with the decrease in tumor vessels size (see above). The observation that increased Tie2 phosphorylation can be induced by both Ang1 treatment and VE-PTP inactivation strongly support a role of VE-PTP as a negative regulator of angiopoietin-Tie pathway although dephosphorylating Tie2 receptor tyrosine kinase.

Discussion

Previous studies of teratomas generated from mouse ES cells have noted the presence of clusters of striated muscle cells (27) and glandular-like epithelial structures (28), similar to the cell type-specific structures observed in the present study. In addition, studies of teratomas generated from human ES cells have noted the formation of structures with markers of lymphatic vessels (16), although, similar to the current study, the frequency of such structures was low. Previous studies have also noted the existence of ES-derived vascular endothelial cells in teratomas (16, 29), although another study was unable to detect such cells (30). In our studies, the use of endothelial cell-specific β-gal reporter allowed for unambiguous identification of robust vascular networks throughout the teratomas, as well as in-depth comparisons of ES-derived vessels versus host-derived vessels. It is not known whether particular lines of ES cells show greater propensity to differentiate into vascular cells within a teratoma, and if so, what factors could promote or inhibit this differentiation. Application of the current methodology in other laboratories, using similar and different ES cell lines, will enable further comparisons.

The key role of the VEGF pathway in endothelial cell development and blood vessel formation (4–6) was further emphasized in the ES cell tumors, as the number of vascular structures derived from VEGF-R2 KO ES cells was greatly reduced. However, as a subtler feature, and unlike VEGF-R2-null embryos that fail to develop any blood vessel structures (4), ES cells lacking VEGF-R2 did develop occasional large-diameter blood vessels, revealing the capability of VEGF-R2-null cells to participate in vessels.

Having validated the potential of the ES tumor model in studying the role of signaling pathways in tumor angiogenesis, we decided to use it to explore the role of VE-PTP and the angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway. An elegant recent study used antibodies to pharmacologically perturb VE-PTP activity in both cultured cells as well as in explant and developmental models (31). However, VE-PTP's actions have not been previously manipulated in tumor vessels. In ES cell tumors, VE-PTP KO blood vessels were enlarged, extending the findings in yolk sacs of VE-PTP-deficient embryos (9, 10), and strongly supporting the findings in explant models (31). Such a phenotype also resembles the effect of tissue-specific transgenic overexpression of the Tie2 ligand, Ang1 (21, 32) or prolonged treatment with exogenous Ang1 (20, 22). Importantly, the enlarged vessels in ES tumors could be returned to normal size by treatment with angiopoietin inhibitors. Although VE-PTP had been speculated to down-regulate the angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway in vivo (19), solid evidence has been lacking because of the difficulty of genetic and pharmacologic approaches. Our findings of increased Tie2 phosphorylation in VE-PTP null teratomas, both under baseline conditions and following systemic treatment with Ang1, establish a clear role for VE-PTP in down-regulating Tie2 activity in tumor angiogenesis. The increased Tie2 phosphorylation was reduced to baseline levels by systemic treatment with angiopoietin inhibitors. Together, our observations support a model in which angiopoietin-induced activation of Tie2 helps regulate the diameter of tumor vessels. Much of the activity of this pathway is normally controlled by VE-PTP via its actions on Tie2 (Fig. S3). By deleting VE-PTP in tumor vessels, the role of VE-PTP and the Ang-Tie2 pathway in regulating tumor vessel diameter was clearly revealed. These results have important implications for antiangiogenic therapy, namely, that targeting the angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway may reduce tumor vessels size and, hence, provide a previously unrecorded mechanism to restrict tumor perfusion.

In summary, our results show that targeting of endothelial cell genes in ES cell tumors can extend the analysis of vascular phenotypes observed in embryonic development, in part by dissociating the requirement of a gene or pathway from the developmental program. In the present study we have focused on the blood vasculature of the teratomas. However, other cell-specific lineages and structures are formed from the ES cells, including epithelial and muscle cells, and these other cell types could also be studied using this model. By combining gene deletion with specific pharmacologic treatments, it is feasible to manipulate signaling systems in unique ways in vivo. Gene targeting in ES cell tumors can provide a powerful and flexible tool to analyze the role of specific angiogenic signaling pathways in tumor angiogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Construction of Genetically Modified ES Cells.

All of the genetically modified ES cell lines were produced by homologous recombination of engineered bacterial artificial chromosomes, using Velocigene technology, as previously described (18). Homozygously targeted ES cells were generated by sequential replacement of both alleles of the targeted gene using vectors with separate drug-selection cassettes. ES cell line F1H4, a hybrid of C57BL/6 and 129 strains, was used as the parental line for all of the studies described here. The application of genetic manipulation in the ES tumor system is best suited to genes encoding receptors and other cell-autonomous genes that are expressed specifically by a particular cell type. In addition, replacing the gene of interest with a reporter is very useful. In this way, the effects of the genetic manipulation will manifest largely in the cells that express the reporter gene, and will not be confounded by effects in other cell types. For example, in the current studies, if other nonvascular cell types express the gene of interest, then interpreting the results of genetic manipulations is much more complex.

Tumor Implantation, Monitoring, and Harvest.

Tumor studies were performed in accordance with Regeneron's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Typically, 2 × 106 ES cells were implanted s.c. into SCID mice (Taconic Farms, Inc) (8 to ≈10 weeks old). In some experiments, when tumors reached approximately 100 mm3 in size, mice were treated by i.p. injection of hFc (control protein, 25 mg/kg, three times a week), a soluble recombinant angiopoietin-1 (24) (25 mg/kg, three times a week), or a peptide-Fc fusion protein, which inhibits angiopoietin-2 as well as more weakly inhibiting angiopoietin-1 [15 mg/kg, two times a week (25, 26)]. Mice were monitored closely for tumor growth and appearance and overall health, until killed. Tumors were cut into slices with a razor blade and fixed in 4% formaldehyde, washed in PBS and stained with X-Gal (Invitrogen) at 4 °C for up to 48 h, then cleared in glycerol (33).

See SI Text for more information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank C-Y. Kao, D. Hylton, T. Solomon, B. Li, Y. Chang, and N. Yuan for technical assistance, Y. Xue for assistance with targeting vector design, and I. Noguera-Troise, S. Wiegand, A. Murphy, A. Eichten, and S. Davis for scientific input.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0911189106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ferrara N, Kerbel RS. Angiogenesis as a therapeutic target. Nature. 2005;438:967–974. doi: 10.1038/nature04483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folkman J. The role of angiogenesis in tumor growth. Semin Cancer Biol. 1992;3:65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson EJ. Using embryonic stem cells to introduce mutations into the mouse germ line. Biol Reprod. 1991;44:238–245. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod44.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shalaby F, et al. Failure of blood-island formation and vasculogenesis in Flk-1-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;376:62–66. doi: 10.1038/376062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrara N, et al. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature. 1996;380:439–442. doi: 10.1038/380439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmeliet P, et al. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature. 1996;380:435–439. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gale NW, et al. Angiopoietin-2 is required for postnatal angiogenesis and lymphatic patterning, and only the latter role is rescued by Angiopoietin-1. Dev Cell. 2002;3:411–423. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suri C, et al. Requisite role of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the TIE2 receptor, during embryonic angiogenesis. Cell. 1996;87:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81813-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumer S, et al. Vascular endothelial cell-specific phosphotyrosine phosphatase (VE-PTP) activity is required for blood vessel development. Blood. 2006;107:4754–4762. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dominguez MG, et al. Vascular endothelial tyrosine phosphatase (VE-PTP)-null mice undergo vasculogenesis but die embryonically because of defects in angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3243–3248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611510104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossant J, Papaioannou VE. The relationship between embryonic, embryonal carcinoma and embryo-derived stem cells. Cell Differ. 1984;15:155–161. doi: 10.1016/0045-6039(84)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart CL, Vanek M, Wagner EF. Expression of foreign genes from retroviral vectors in mouse teratocarcinoma chimaeras. EMBO J. 1985;4:3701–3709. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viloria-Petit A, et al. Contrasting effects of VEGF gene disruption in embryonic stem cell-derived versus oncogene-induced tumors. EMBO J. 2003;22:4091–4102. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi YP, Ferrara N. Oncogenic ras fails to restore an in vivo tumorigenic phenotype in embryonic stem cells lacking vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;254:480–483. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnusson PU, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta constitutive activity promotes angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2142–2149. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000282198.60701.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerecht-Nir S, et al. Vascular development in early human embryos and in teratomas derived from human embryonic stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:2029–2036. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.031930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy K, Carthew P, Handyside AH, Hooper ML. Extragonadal teratocarcinoma derived from embryonal stem cells in chimaeric mice. J Pathol. 1990;160:71–76. doi: 10.1002/path.1711600114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valenzuela DM, et al. High-throughput engineering of the mouse genome coupled with high-resolution expression analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:652–659. doi: 10.1038/nbt822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fachinger G, Deutsch U, Risau W. Functional interaction of vascular endothelial-protein-tyrosine phosphatase with the angiopoietin receptor Tie-2. Oncogene. 1999;18:5948–5953. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baffert F, et al. Age-related changes in vascular endothelial growth factor dependency and angiopoietin-1-induced plasticity of adult blood vessels. Circ Res. 2004;94:984–992. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000125295.43813.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thurston G, et al. Leakage-resistant blood vessels in mice transgenically overexpressing angiopoietin-1. Science. 1999;286:2511–2514. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thurston G, et al. Angiopoietin 1 causes vessel enlargement, without angiogenic sprouting, during a critical developmental period. Development. 2005;132:3317–3326. doi: 10.1242/dev.01888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vikkula M, et al. Vascular dysmorphogenesis caused by an activating mutation in the receptor tyrosine kinase TIE2. Cell. 1996;87:1181–1190. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis S, et al. Angiopoietins have distinct modular domains essential for receptor binding, dimerization and superclustering. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:38–44. doi: 10.1038/nsb880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daly C, et al. Angiopoietin-2 functions as an autocrine protective factor in stressed endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15491–15496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607538103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliner J, et al. Suppression of angiogenesis and tumor growth by selective inhibition of angiopoietin-2. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:507–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore R, Radice GL, Dominis M, Kemler R. The generation and in vivo differentiation of murine embryonal stem cells genetically null for either N-cadherin or N- and P-cadherin. Int J Dev Biol. 1999;43:831–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taverna D, Hynes RO. Reduced blood vessel formation and tumor growth in alpha5-integrin-negative teratocarcinomas and embryoid bodies. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5255–5261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu J, et al. Contribution of host-derived tissue factor to tumor neovascularization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1975–1981. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.175083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winderlich M, et al. VE-PTP controls blood vessel development by balancing Tie-2 activity. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:657–671. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suri C, et al. Increased vascularization in mice overexpressing angiopoietin-1. Science. 1998;282:468–471. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams NC, Gale NW. In: Principles and Practice: Mammalian and Avian Transgenesis–New Approaches. Pease S, Lois C, editors. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 131–172. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.