Abstract

Background

Flood-tolerant tree species of the Amazonian floodplain forests are subjected to an annual dry period of variable severity imposed when low river-water levels coincide with minimal precipitation. Although the responses of these species to flooding have been examined extensively, their responses to drought, in terms of phenology, growth and physiology, have been neglected hitherto, although some information is found in publications that focus on flooding.

Scope

The present review examines the dry phase of the annual flooding cycle. It consolidates existing knowledge regarding responses to drought among adult trees and seedlings of many Amazonian floodplain species.

Main Findings

Flood-tolerant species display variable physiological responses to dry periods and drought that indicate desiccation avoidance, such as reduced photosynthetic activity and reduced root respiration. However, tolerance and avoidance strategies for drought vary markedly among species. Drought can substantially decrease growth, biomass and photosynthetic activity among seedlings in field and laboratory studies. When compared with the responses to flooding, drought can impose higher seedling mortality and slower growth rates, especially among evergreen species. Results indicate that tolerance and avoidance strategies for drought vary markedly between species. Both seedling recruitment and photosynthetic activity are affected by drought,

Conclusions

For many species, the effects of drought can be as important as flooding for survival and growth, particularly at the seedling phase of establishment, ultimately influencing species composition. In the context of climate change and predicted decreases in precipitation in the Amazon Basin, the effects of drought on plant physiology and species distribution in tropical floodplain forest ecosystems should not be overlooked.

Key words: Drought responses, Amazonia, floodplain forests, tree ecology, várzea

INTRODUCTION

Amazonian floodplain forest ecosystems are maintained primarily by the nature of their hydrological regime, including periods of wetting and drying (Fig. 1). In these forests, the flood regime is recognized as a key driver of forest community structure and adaptive physiological responses. Recent reviews summarize tree responses to annual waterlogging and submergence in detail (Parolin, 2009). However, the role of the dry periods has been mostly ignored for Amazonian floodplains, despite growing evidence of the importance of drought for species distribution patterns in other tropical floodplains (Lopez and Kursar, 2007) and tropical rain forests (Engelbrecht et al., 2007). Among the first to raise the relevance of the dry phase in Amazonian floodplains were Keel and Prance (1979) who stated that drought may represent more limitations for survival than flooding for the local vegetation. However, little further study or analysis has since been published. Therefore, the goal of the present review is rectify this shortcoming by assembling and assessing evidence that periods of drought occurring during the dry phase alter Amazonian floodplain forests as a result of differential species responses, especially among seedlings and juvenile trees.

Fig. 1.

Seasonal extremes in the Amazonian floodplains: (left) high-water period with waterlogged trees, and (right) development of drought.

Drought is defined by insufficient water availability for plants, a consequence of soil moisture depletion by low precipitation and high evapotranspiration rates. Although operational definitions propose climatic indices for drought by precipitation and evapotranspiration below ecosystem-specific minima (Quiring, 2009), drought is generally defined with reference to plant responses (Gutschick and BassiriRad, 2003; Neumann, 2008). Plants may experience drought as drought stress, which is tolerated or avoided by morphological, physiological and phenological mechanisms. Like other environmental stresses, drought events have duration, frequency and severity, as measured by a combination of climate and impact data on plant productivity. For the purposes of understanding the occurrence of drought in Amazonian floodplains and species-specific responses, we consider drought stress as insufficient water availability to sustain normal plant metabolism (Lichtenthaler, 1998).

In Amazonian floodplains, drought stress is mainly caused by low soil moisture availability in silty soils coupled with high evaporation rates during dry periods. The duration of the dry season in floodplain forests varies considerably along the rainfall gradient across the Amazon Basin (Sombroek, 2001). Floodplains are subjected to 1–5 consecutive months of precipitation below 100 mm month−1 from the western Amazon to the Dry Belt Region in the eastern Amazon (Sombroek, 2001). The dry season coincides with the termination of flooding and the end of the rainy season (Worbes, 1986), when the top horizons of soils lose sufficient moisture to reduce soil water availability to wilting point (Fig. 2). In addition, El Niño supra-annual climatic events cause regular drought in floodplains, reducing rainfall and increasing moisture loss by wind transport and raising average temperatures (Walsh and Newberry, 1999; Schöngart and Junk, 2007; Marengo et al., 2008). In contrast to many other stress factors, drought stress does not start abruptly but increases gradually over time (Larcher, 2001), emphasizing the importance of drought duration for plant survival.

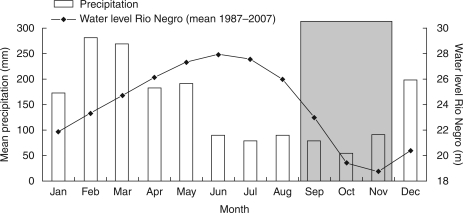

Fig. 2.

Mean precipitation and water level in central Amazonia, with timing of flooding and drought in normal years. The driest months are highlighted by shading.

Trees of Amazonian floodplains have evolved a suite of traits to cope with flooding and drought (Chaves et al., 2003). The efficacy of these adaptations for drought tolerance or avoidance can be studied by measuring physiological responses, growth and survival. Trees have age-specific responses and different susceptibilities to environmental stresses (Kozlowski and Pallardy, 2002), and, as such, the physiological responses for seedlings, juveniles and adult trees belonging to different species are addressed here. While many studies focus on flood tolerance as a key mediator for seedling population and community dynamics, the few available studies suggest that drought can also play an important role on seedling survival, which in turn triggers changes in tree species composition and distribution (Parolin, 2001; Elcan and Pezeshki, 2002; Stroh et al., 2008).

In the present paper, the potential occurrence and effect of drought (water deficiency) on floodplain woody plants during the dry season is discussed. Two main questions are addressed: (1) which phenological, anatomical and physiological responses can be observed at different drought intensities? (2) how do these responses influence mortality and species distributions of Amazonian floodplain trees?

THE AMAZONIAN FLOODPLAIN ECOSYSTEM

Amazonian floodplains extend over 300 000 km2 and hold >1000 tree species (Wittmann et al., 2006) that have evolved a suite of adaptive traits to cope with annual cycles of flooding and drying (Junk et al., 1989; Parolin et al., 2004). They experience intra-annual fluctuations with changes in river-water levels of up to 12 m, known as the ‘flood pulse’, which last >7 months a year (Junk et al., 1989). Annual precipitation in equatorial Amazonia generally amounts to >2000 mm, with a distinct increase from east to west (Sombroek, 2001). Precipitation is clearly periodic, with a rainy season from December/January to April/May and a dry season from June/July to October/November (Fig. 2). There is a lag time of 3–4 months between the rainy season and the flood season, whereby floods rise after the onset of the rainy season and fall after the rainy season has ended (Fig. 2). As such, floodplain vegetation is subjected to a limited ‘dry period’ of low flood levels and low rainfall, where monthly evaporation can exceed precipitation (Irion et al, 1997; Junk and Krambeck, 2000). To differentiate between the short dry period and the extended non-flooded period, we refer to the ‘dry season’ or ‘dry phase’ as the period of time during which vegetation is not flooded.

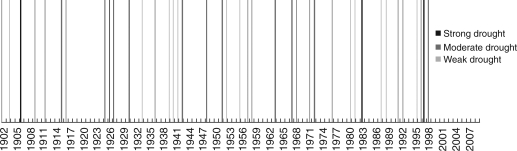

Droughts of varying intensities have occurred in the Amazon Basin in the past centuries (Fig. 3), as indicated by severe droughts in 1925–26, 1860, and 1774 that had pronounced effects on both upland and floodplain forests, i.e. by increased forest flammability and widespread fires (Sternberg, 1987; Sombroek, 2001, Williams et al., 2005; Marengo et al., 2008). Most drought events are related to El Niño Southern Oscillations (ENSO), which cause lower flood-levels and prolonged dry periods in Amazonian floodplains (Adis and Latif, 1996; Marengo and Nobre, 2001). During the 20th century, extended dry periods and associated droughts occurred on average every 4·35 years [see Quinn and Neal (1992) for the period 1925–1982, and Schöngart et al. (2004) for the period 1800–2000]. Mean precipitation during such dry periods is significantly lowered by approx. 36 %, with maximum reductions of up to 50 % (Marengo et al., 2008), and the start of the rainy season is delayed by up to 2 months (January to March) (Schöngart et al., 2004). The last three decades have been marked by unusually strong El Niño events in 1982/83, 1997/98, prolonged dry periods from 1990 to 1995 and a recent severe drought in 2005 unrelated to El Niño (Marengo et al., 2008).

Fig. 3.

Exceptional droughts in the past century (data from Sombroek, 2001) with strong, moderate or weak droughts (no definitions available for specification of precipitation amount and soil water availability).

The soils of Amazonian floodplains are alluvial-hydromorphic (Oliveira et al., 2000). Where a marked dry season occurs, pockets of vertisols may also develop within the periodically inundated white-water floodplains (várzea; Roosevelt, 1980). In várzea forests, soil porosity averages 46 %. Soils are silty, but sand and clay grain sizes may be prevalent depending on the distance and elevation of sites relative to the river level (Wittmann et al., 2004). Root biomass and root production in black-water floodplains (igapó) and várzea are mainly restricted to the upper 30 cm of the soil (Meyer, 1991; Worbes, 1997). Dry bulk density ranges between 1·3 and 1·6 g cm−3 in central Amazonian floodplains near Manaus (3°15′S, 59°58′W; Oliveira et al., 2000), in Santarém further east dry bulk density varies from 0·9 to 1·6 (C. Lucas, unpubl. res.).

Soil water content in forested levees varies with depth and time, mainly influenced by rainfall and the flood pulse. During flood drawdown, mean water content of the soil profile varies between 23 and 33 %, as compared with a mean water content of 33–42 % (equivalent to 66–84 % water-filled pore space) after the onset of rain (Kreibich, 2002). Differences between soil layers are prominent, with the driest soils at 20–60 cm depth and the wettest layers below the water-table at 300–450 cm depth (Worbes, 1986; Kreibich, 2002).

ADAPTIVE TRAITS FOR DROUGHT TOLERANCE/DESSICATION RESISTANCE

Many of the same anatomical characteristics that help a plant survive flooding can also alleviate drought stress. Adventitious roots, aerenchyma, leathery xeromorphic leaves, etc., encountered in Amazonian floodplain tree species commonly recognized as adaptations to flooding stress (Parolin et al., 2004; Wittmann and Parolin, 2005) may alleviate stress associated with drying as well. Floodplain tree adaptations to drought may have evolved on the floodplain during dryer glacial epochs (e.g. Late Pleistocene) or may be traits retained from upland species or genera that migrated into the floodplains. Given that some floodplain tree species may have originated in adjacent savannas and uplands where drought events are frequent and common (Prance, 1979; Kubitzki, 1989; Wittmann et al., 2009), adaptive traits that tolerate or avoid water stress may be prevalent.

Leaves

Morphological adaptations against drought stress include small, thick leaves with sclerophyllous structures and increased epicuticular waxes to reduce transpiration (Medina, 1983; Waldhoff et al., 1998). Such structures are found in the leaves of most Amazonian floodplain tree species as protection against excess evaporation, heat and light (Roth, 1984; Schlüter, 1989; Waldhoff and Furch, 2002; Waldhoff, 2003). Epidermal leaf structures such as waxes or hairs can reflect light to protect leaves from high solar irradiance. The common floodplain pioneer Cecropia latiloba has a white abaxial leaf surface that may reflect light reflected off the water surface at high water, while also reflecting high irradiance during dry periods with low cloud cover. Glandular and non-glandular hairs were found on leaves from several woody floodplain species, including Cassia leiandra, Nectandra amazonum and Pouteria glomerata (Waldhoff and Furch, 2002; Waldhoff, 2003). The abaxial leaf surface of Licania apetala, Senna reticulata, Cassia leiandra and Quiinia rhytidopus is covered with papillae that may also protect leaves from reflected irradiance. Additionally, stomata are abaxial and sunken in many species. In the palm Astrocaryum jauari, a waxy structure is located above the stomata to further inhibit evaporation (Schlüter, 1989). Epicuticular waxes are also found on leaf blades of many floodplain tree species (Waldhoff and Furch, 2002; Waldhoff, 2003). Although these waxes may function primarily to prevent water influx in inundated leaves (Fernandes-Côrrea and Furch, 1992; Schlüter and Furch, 1992), they also enhance drought resistance by decreasing cuticular water loss and preventing photodamage.

Vegetative phenology

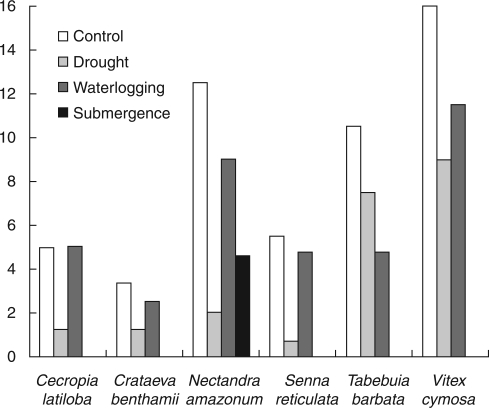

The peaks of leaf fall are during flood drawdown (August to September) and at the onset of the rainy season (November to December) in central Amazon floodplains (Worbes, 1997). Thus, during dry periods, leaf shedding may be an adaptation to avoid drought stress by decreasing the transpiring surface area (Borchert, 1983; Medina, 1983; Wright and Cornejo, 1990), or by the production of smaller leaf surfaces or fewer leaves (Fig. 4; Parolin et al., 2005). However, there is little evidence for an adaptive advantage of deciduous over evergreen species in Amazonian floodplains (Parolin, 2001). The variation in timing of leaf senescence may also be a phylogenetically retained trait adapted to environments in which the species evolved. For example, many genera of the Bombacaceae originated in semi-arid environments and are thus adapted to tolerate periodical drought, using strategies such as leaf shedding to decrease transpirational water loss (Kubitzki, 1989).

Fig. 4.

Leaf number after 12 weeks of experimental conditions (control, drought, waterlogging and submergence) in seedlings.

RESPONSES OF AMAZONIAN FLOODPLAIN TREE SPECIES TO DRY PERIODS AND DROUGHT

Whether Amazonian floodplain tree species experience drought conditions is questionable, given shallow water-tables and deep tap-root access to water levels among some species during dry periods. However, there are measurable physiological changes in plants that can indicate whether plants are susceptible to drought and respond to water stress (Table 1). They may portray strategies to prevent excessive water loss and desiccation (Kozlowski and Pallardy, 2002), ultimately avoiding desiccation or drought stress. Here evidence for physiological changes in floodplain trees is discussed that suggest internal regulation of water balance in dry periods and exceptionally dry years. This is followed by a discussion on seedling responses to experimental drought.

Table 1.

Summary of published results on the physiological responses among floodplain forest tree species that could indicate regulation of water status for the avoidance of drought stress during dry periods

| Physiological trait | Response | Value | Species | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf phenology | Senescence | − | None | Parolin et al. (2005) |

| Leaf water potential | Decrease | −1·24 to −2·7 MPa | Laetia corymbulosa | Armbrüster et al. (2004) |

| Photosynthetic CO2 uptake | Decrease | 4–14 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1 | Pseudobombax munguba | Waldhoff et al. (1998) |

| Stomatal conductance | Decrease | <100 mmol m−2 s−1 | None, except Crataeva benthamii | Parolin (2000) |

| Root respiration | Decrease | 50–60 µL O2 g f. wt and 40–90 µL O2 g f. wt | Astrocaryum jauari and Macrolobium acaciifolium (juvenile) | Schlüter (1989) |

| Vitamin E | Increase | α-Tocopherol 6 µg m−2 and δ-tocotrienol 9 µg m−2 | Garcinia brasiliensis (seedling) | Oliveira-Wittmann (2006) |

All traits were measured on plants in the field in the Manaus region except Vitamin E concentrations, which were measured on seedlings subjected to experimental drought.

Physiological responses and water status regulation

Photosynthetic CO2 uptake.

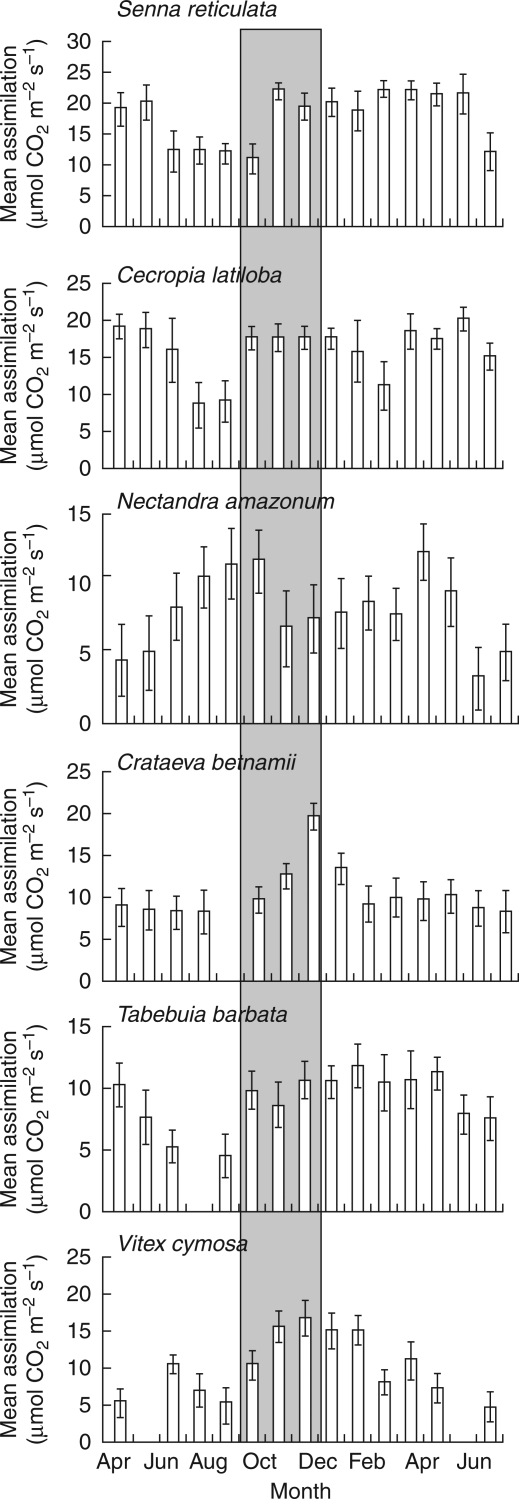

Some Amazonian floodplain trees respond to water shortage by decreasing photosynthetic CO2 assimilation (Schlüter, 1989; Parolin, 2000; Armbrüster et al., 2004). For example, light response curves of Pseudobombax munguba showed a decrease inassimilation from 14 to 6 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1 during a 1-month dry period, dropping to 4 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1 after a 4-month dry period (Waldhoff et al., 1998). In contrast, during the driest months (September to November), the evergreen Cecropia latiloba and the deciduous Tabebuia barbata and Vitex cymosa showed abrupt increases in photosynthetic CO2 assimilation, most likely a result of recent new leaf expansion (Fig. 5). With subsequent flooding of roots, tree water status decreased, leaves were shed to reduce transpirational surface and water loss, and photosynthetic assimilation decreased as a consequence of lower photosynthetic capacity of senescent leaves (Sesták, 1985; Reich et al., 1999). Species that maintain constant photosynthetic activity under mild drought conditions include Eschweilera tenuifolia, Hevea spruceana, Nectandra amazonum and Pouteria glomerata (Parolin, 2000; Maia and Piedade, 2002), probably due to deep root systems that supply water to the trees (Armbrüster et al., 2004).

Fig. 5.

Mean monthly photosynthetic CO2 assimilation at maximum quantum flux (Amax) of six species measured between April 1994 and June 1995. The number per species and month = 10. The driest months are highlighted by shading.

Transpiration and stomatal conductance.

In dry conditions, transpirational losses are high, and soil water availability in the upper profile is too low to compensate for the increased water demands, thus causing negative water balances in plants with shallow root systems. Therefore, reductions in transpiration and prevention of xylem cavitation are important for tree survival and growth during drought (Poorter and Markesteijn, 2008). However, due to inhibition of aerobic root respiration during the flood season, greater reductions in transpiration are observed in the flooded period than in the dry period for many floodplain tree species (Parolin, 2000).

Stomatal conductance for CO2 or water vapour is an index of stomatal aperture (Buschmann and Grumbach, 1985). In six tree species [0]from Amazonian várzea (Parolin, 2000), stomatal conductance ranged between 200 and 400 mmol m−2 s−1, decreasing 5–35 % in the flood season. Stomatal conductance peaked at the end of the waterlogged period, when trees bore their oldest leaves and displayed the lowest CO2 assimilation. Only in Crataeva benthamii was there a decrease in stomatal conductance in the dry period (September) of <100 mmol m−2 s−1. With the present data, patterns in stomatal conductance suggest that the measured trees did not experience water stress during average dry periods.

Leaf water potential.

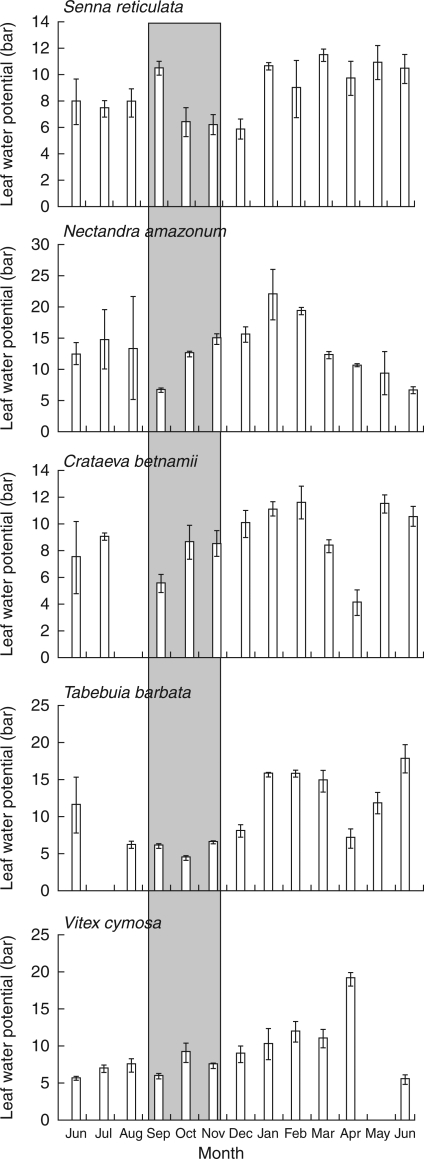

Leaf water potential, an indicator of plant water balance (Fernandes-Corrêa and Furch, 1992), ranges between an average of −0·76 and −1·5 MPa among Amazonian floodplain trees (P. Parolin, unpubl. res.). Mean monthly leaf water potentials vary between species, and intra- and inter-annual differences are substantial but with no apparent link to the hydric status (Fig. 6). However, leaf water potentials in the driest months tend to be continuously low across years. For example, Laetia corymbulosa, a tree species not particularly resistant to desiccation, has the lowest negative values during the dry months of the terrestrial period (−1·24 to −2·7 MPa in October/November, as compared with −0·18 to −0·33 MPa for the remainder of the year; Armbrüster et al., 2004).

Fig. 6.

Mean leaf water potential (bar) of five species measured between June 1994 and June 1995. Number of leaves measured per species and month = 5. The driest months are highlighted by shading.

Xylem flux.

Xylem flux density in deciduous trees is strongly influenced by tree phenology (Horna et al., 2009). Decreasing soil moisture availability does not lead directly to leaf damage but might indirectly trigger leaf-shedding by hormone signals to prevent plant water loss. Sap fluxes decrease simultaneously with prolonged leaf shedding in five tree species (Parolin et al., 2005). Stem water storage can buffer water shortage during the daytime (Müller, 2002; Parolin et al., 2005). Overall, water balance, osmotic relations and turgor are poorly understood aspects of Amazonian floodplain tree physiology, especially in relation to drought as measurements are often recorded during the flooded period.

Root respiration.

While tree metabolism may be unaffected in average dry years, exceptional droughts may decrease root respiration, particularly among juvenile trees. In a study of the palm Astrocaryum jauari and the legume tree Macrolobium acaciifolium, root respiration was measured in the field (Schlüter, 1989). Contrary to adults, juvenile Astrocaryum jauari have a shallow rooting system, reaching only 50 cm depth until the age of 6 years, making them vulnerable to low soil moisture availability. In contrast, Macrolobium acaciifolium forms a deep taproot. For both species a marked decrease in root respiration was observed during an exceptionally dry period of low rainfall (October to November in 1986 and 1987). While oxygen turnover increased continuously after the end of the flood season, root respiration dropped from 110 µL O2 g f. wt to 50–60 µL O2 g f. wt in A. jauari, and from 170–180 µL O2 g f. wt to 40–90 µL O2 g f. wt in M. acaciifolium (Schlüter, 1989). This drop in oxygen consumption by roots may be a direct response to low water availability in soils, or indirectly due to reduced ion transport in the rhizosphere.

Proteins and vitamins.

The production of vitamin E (α-tocopherol, an antioxidant) in foliar tissue is known to reduce drought-induced stress. To date, only laboratory-based data exist regarding this parameter. In drought treatments, the highest concentrations of α-tocopherol and δ-tocotrienol were found in the leaves of Garcinia brasiliensis (Oliveira-Wittmann, 2006). Within 90 d of the start of drying, the levels of α-tocopherol rose from 2 to 6 µg m−2, while concentrations of δ-tocotrienol reached 9 µg m−2. In correlation with increased vitamin E, seedlings displayed slower growth rates and lower photosynthetic activity under drought. Under normal metabolic conditions, the formation of oxygen radicals and the peroxidation of lipidic membranes are in a dynamic equilibrium with the activity of the antioxidant systems (Blokhina, 2000). With the stresses associated with drought, this equilibrium may be disturbed and lead to oxidative stress, as observed in Garcinia brasiliensis (Oliveira-Wittmann, 2006).

Seedling responses to drought

Seed germination.

Seeds of Amazonian floodplain trees are especially vulnerable to drought. Seed viability when exposed to air after dispersal is brief, drying out or rotting within a few days (e.g. Tabebuia barbata and Nectandra amazonum) or weeks (e.g. Senna reticulata and Aldina latifolia; Parolin et al., 2009). Many floodplain trees fruit during the flood season, releasing seeds during flooding, and germination generally is initiated when floods recede (Parolin et al., 2004). Seeds are thus exposed to aerobic conditions, and readily germinate on moist or wet sediment and soils. If, thereafter, water availability rapidly declines in upper soil layers, seedling establishment may be severely limited (Worbes, 1986).

Seedling growth and biomass allocation.

Seedling establishment and early growth occur during the dry phase. They are subjected to water shortage for approx. 4 weeks before the onset of the rainy season (Fig. 2) which causes substantial reductions in height growth, leaf number and stem diameter (Parolin, 2001; Waldhoff et al., 1998, 2000).

High biomass investment to the root system was documented for seedlings of Cecropia latiloba, Senna reticulata and Vitex cymosa where the root : shoot ratio increased significantly after 12 weeks of drought as compared with the control treatment (Waldhoff et al., 1998) indicating a strategy for desiccation resistance. However, in other species (e.g. Crataeva benthamii, Nectandra amazonum and Tabebuia barbata) although the root : shoot ratio decreased under drought stress, they grew well in dry conditions.

Seedling survival.

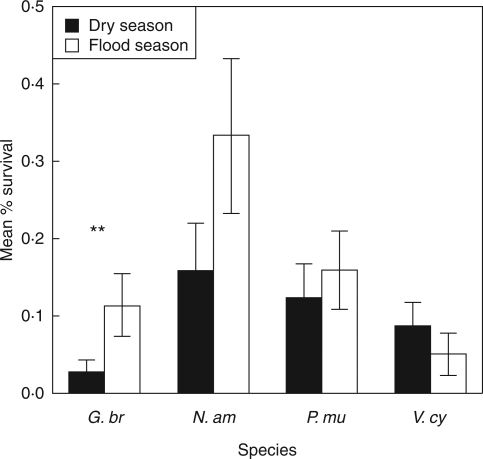

In a field study, tree seedling mortality was higher during the dry season than during flooding (Ziburski, 1990; Oliveira-Wittmann et al., 2009). Seedling mortality in the dry season, particularly during low rainfall, was 100 % among Vitex cymosa, 97 % among Crataeva benthamii, 70 % among Senna reticulata and Psidium acutangulum, and 33 % in Eschweilera ovalifolia (Oliveira-Wittmann et al., 2009). Mortality was consistently higher during the dry season than during submergence, suggesting that Amazonian floodplain tree seedlings have a higher resistance to submergence than drought. The mortality of tree species in a common or garden experiment suggests that deciduous species have a higher resistance of drought during early seedling establishment than evergreen species (Fig. 7; C. Lucas, unpubl. res.).

Fig. 7.

Average seedling mortality with standard error bars, of two evergreen várzea tree species, Garcinia brasiliensis (G. br) and Nectandra amazonica (N. am) and two deciduous species, Pseudobombax munguba (P. mu) and Vitex cymosa (V. cy) in the dry versus flooded season, as indicated. Data are averaged across 21 plots in three forest stands in the dry versus flooded season in a common or garden experiment in the Lower Amazon region of Santarém-PA. Two-way t-tests comparing within species means are significant (*) for G. br (t = −2·04, df = 27, P = 0·05); but non-significant for N. am (t = −1·94, df = 29, P = 0·062); P. mu (t = −0·51, df = 40, P = 0·61); or V. cy [t = 1·00, df = 42, P = 0·32 (R version 2.9.0, www.r-project.org/)] (C. Lucas, unpubl. res.).

Ecosystem responses to drought

The combined effects of drought on plant photosynthesis, transpiration and respiration have broad implications for ecosystem carbon budgets. Based on measurements from five adult floodplain tree species, severe drought conditions correlated with low total ecosystem respiration REd, whereas photosynthetic activity was moderately reduced and no change in canopy structure was observed (Horna, 2002). Thus, trees displayed a relative increase in carbon uptake (64·6 g C m−2), due to the combined effect of low CO2 loss by roots and moderate C gain by above-ground live biomass. Total carbon output of above-ground woody tree biomass of a central Amazon floodplain forest during the dry period (November to January) averaged an annual low of 360 g C cm−2, peaked at 550 g C cm−2 during rising water (February to April), then gradually dropped to 480 g C cm−2 at high water levels (May to July) and 420 g C cm−2 with receding water levels (August to October) (Horna, 2002). Carbon output rates from tree branch surfaces varied with species and time of day, but were generally low in the dry season and with no diurnal variation.

DISCUSSION

This review provides evidence for species responses to water stress during dry periods of the annual flooding cycle in Amazonian floodplain forests, particularly among seedlings and juveniles. Differential species responses to dry periods suggest that some tree species regulate internal water balance during dry periods, which may avoid drought stress. Seedlings were the only phase in floodplain-tree life history to provide evidence for differential growth and survival among species that could eventually alter species composition. Although drought occurs in Amazonian floodplains (Marengo et al., 2008), there remains a missing link as to whether or not adult and juvenile trees experience drought stress sufficient to induce mortality, alter fertility and affect species distribution.

Adult trees have both morphological traits and physiological strategies that may reduce excessive water loss during the dry season. Tropical floodplain tree species reduce evapotranspiration with similar traits employed by upland and savannah species, including epicuticular waxes, trichomes, reflective surfaces and papillae. Given that trees potentially can experience physiological water stress during dry periods and flood periods (Tournaire-Roux et al., 2003), trees may employ similar strategies for avoiding water loss during dry and wet seasons. It was found that some species reduce leaf water potential, foliar surface area and xylem flux thereby reducing transpirational water loss during the dry period. Furthermore, some species reduce photosynthetic rates and root respiration to slow metabolic pathways that require more water. Despite these apparent mechanisms to maintain water potential within trees, there is sparse evidence for adult floodplain tree species suffering mortality or reduced growth during dry periods. Rather, drought-related tissue damage or loss may be avoided by investment in root biomass and changes in vegetative phenology and xeromorphic leaf traits.

In the field and the laboratory, seedlings show species-specific responses to low soil water availability in dry periods. The available data suggest that individuals experiencing drought stress are likely to be at the seedling phase. In contrast to adult and juvenile species, seedlings have shallow root depths and limited rooting systems, making them susceptible to drought stress.

It is found that seedlings exposed to experimental drought are susceptible to high mortality rates during seed germination and seedling establishment phases. Seedling mortality increased during the dry season, particularly among evergreen species (C. Lucas, unpubl. res.). However the dry season coincides with the first 2–3 months of seedling establishment and growth, when seedlings naturally have a higher probability of death (Alvarez-Clare and Kitajima, 2009).

Results of different studies suggest that floodplain species have variable resistance and avoidance strategies for preventing water stress. For some species, drought may impair survival at the seedling phase, potentially influencing future composition and succession of floodplain forests. Seedling recruitment and photosynthetic activity are affected by drought events and may thus lower net productivity and shift species composition.

Several hundred tree species with differing life-history traits survive the extreme hydric conditions of Amazonian floodplains with the aid of diverse strategies which have evolved to alleviate both drought and flooding stress. The diversity of species subject to this cyclical recurrence of hydric stresses, particularly at the more vulnerable seedling phase, demonstrates that many species may evolve to tolerate overlapping extreme stresses. Flood and drought stress may result in both advantages and disadvantages for floodplain species growth and survival; e.g. exposure to drought at seedling stages may enhance drought resistance at later stages by early investment in below-ground biomass (Kozlowski and Pallardy, 2002). However, in contrast to their upland counterparts, growth by floodplain trees is restricted to the non-flooded season, coinciding with the dry season.

Several studies show that dry spells and drought frequency and severity, such as those associated to El Niño events, can shape species distribution in tropical wet and dry forests (Borchert, 1994; Engelbrecht and Kursar, 2003; Lopez and Kursar, 2003; Engelbrecht et al., 2005; Poorter and Markesteijn, 2008). As such, supra-annual extreme environmental conditions may play a key role in plant-species distribution (ter Steege, 1994). Overlooking the impact of severe events may result in failure to identify critical mechanisms structuring ecological communities (Bunker and Carson, 2005). Tree-species distribution, composition, and richness in Amazonian floodplain forests are understood to be largely mediated by the flooding gradient (Junk, 1989; Ayres, 1993; Ferreira, 2000; Wittmann et al., 2002). Tree species are zoned along the flooding gradient, most of them restricted to limited topographic ranges (Wittmann et al., 2004). However, few studies in the region have focused on the impact of drought as a determinant of species distribution. The most-affected species should be highly flood adapted and endemic to the low-várzea, including evergreen pioneer species with small seeds and low water-storage capacity (Borchert, 1994). The alluvial soils at these elevations next to river banks are predominately sandy (Wittmann et al., 2004) and thus plants are subject to rapid desiccation. Disentangling the relative effects of drought, flooding, and light that limit establishment of floodplain species is complex, as pioneer species are light-demanding and as such generally more adapted to drought than late-successional species. In addition, pioneers often make use of mass-dispersing seedlings with generally high mortality rates (Wittmann and Junk, 2003; Oliveira-Wittmann et al., 2007). In more diverse floodplain forests at higher elevations, drought may be a less-limiting factor, as water loss from intermediate clayey soils below a dense-canopy forest is reduced. The regeneration of several late-successional species appear to be timed to dry periods with low-water levels with increased establishment rates during dryer years (e.g. Hura crepitans, Sterculia apetala, Guarea guidonia and Ocotea cymbarum; Marinho, 2008). Further research is needed to understand how these high elevation late-successional species react to drought events in the floodplain.

Origin of drought resistance in Amazonian floodplain trees

Floristic evidence suggests that many Amazonian floodplain species are widely distributed across the Neotropics, including regions with climatically or edaphically induced aridity (Prance, 1979; Kubitzki, 1989; Worbes, 1997). Considering the series of drought and flood periods over a geological time scale, many floodplain species may have evolved drought-resistance or avoidance strategies that have been retained in present-day floodplain species. Flooded forests are proposed as a potential refuge for upland species during previous eras of frequent and prolonged drought (Baraloto et al., 2007) and many of these migrant upland species may have pre-adaptations to cope with flooding and drought especially when they originate from neotropical savannahs.

Climatic changes during the Tertiary and Quaternary affected global sea levels and thus resulted in periodic reductions and expansions of floodplain forest area (Vuilleumier, 1971; Van der Hammen, 1974; Frailey et al., 1988; Tuomisto et al., 1992; Irion et al., 1997; Oliveira and Mori, 1999), where the floodplains acted as linear refuges for sensitive upland species during periods with dryer climatic conditions (Pires, 1984).

Drought in light of climatic changes

Climate change models predict a decrease in annual rainfall, an increase in dry season length and greater inter-annual rainfall variability for the tropics (Bawa and Markham, 1995; Hulme and Viner, 1998; IPCC, 2007). Given this expected increased frequency and severity of drought in the Amazon basin, the effects of drought on floodplain forest ecosystems should not be underestimated. Annual precipitation has declined over much of the humid tropics during the 20th century. Bunker and Carson (2005) suggest that this trend may reduce tropical forest diversity by weakening density-dependent mechanisms that maintain diversity. In addition, plots dominated by dry-forest species experienced higher growth in response to irrigation and also far lower dry-season mortality relative to plots dominated by wet-forest species. Their results suggest that dry-forest species may benefit from any increase in dry season length or severity. To which extent this has to be expected in Amazonian floodplain forests is still not clear. More intense droughts in both frequency and strength are likely to affect Amazonian floodplain forests at both the species and community levels, especially near the flood-induced tree lines. In Amazonian black-waters, forest flammability may increase during extended droughts, leading to possible species losses at local and regional scales. Research which has been conducted during ‘normal’ conditions may overlook the impact of severe events and thus fail to identify critical mechanisms structuring ecological communities (Bunker and Carson, 2005).

Recommendations for future research

The present review highlights the lack of information available to evaluate if Amazonian floodplains experience drought and how species respond to drought stress. With predicted increased drought frequency and severity in the Amazon Basin, it will be important to understand the effects of drought stress on floodplain forests. As such, this review is concluded with proposals for future research:

(a) Investigate whether or not seedlings experience drought stress in the field.

(b) Investigate interactive effects of increased fire frequency and intensity, high temperature stress, and pathogen attacks associated with water stress on floodplain-species distribution.

(c) Explore relationships between drought severity, pathogen attacks, biomass accumulation and woody growth. In the light of habitat destruction and logging, knowledge of basic information to guarantee sustainable forest regeneration and management is still scarce, and further studies are urgently required here.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Professor Jos Verhoeven (University of Utrecht, The Netherlands) and Dr Brian Sorrell (National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Ltd, New Zealand) for inviting the first author to participate in a wonderful symposium (8th INTECOL International Wetlands Conference, Cuiabá, Brazil) where the essence of this review was first presented. Jos Verhoeven and two anonymous reviewers gave extremely valuable comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. We thank the technicians and barqueiros of the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA, Manaus) for helping with field measurements. The studies were financed by the INPA/Max-Planck project. We thank Santarém várzea community members, IPAM and UFPA for logistical support and the ‘Working Forests in the Tropics’ Program and the IAF Grassroots Development Fellowship for financing research in Santarém-PA, Brasil.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adis J, Latif M. Amazonian arthropods respond to El Niño. Biotropica. 1996;28:403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Clare S, Kitajima K. Susceptibility of tree seedlings to biotic and abiotic hazards in the understory of a moist tropical forest in Panama. Biotropica. 2009;41:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Armbrüster N, Müller E, Parolin P. Contrasting responses of two Amazonian floodplain trees to hydrological changes. Ecotropica. 2004;10:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres JMC. Estudos de Mamirauá. I. Brasília, DF: Sociedade Civil Mamirauá; 1993. As matas de várzea do Mamirauá; pp. 1–123. [Google Scholar]

- Baraloto C, Morneau F, Bonal D, Blanc L, Ferry B. Seasonal water stress tolerance and habitat associations within four neotropical tree genera. Ecology. 2007;88:478–489. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2007)88[478:swstah]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawa KS, Markham A. Climate change and tropical forests. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1995;10:348–349. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(00)89130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokhina O. Anoxia and oxidative stress: lipid peroxidation, antioxidant status and mitochondrial functions in plants. University of Helsinki; 2000. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert R. Phenology and control of flowering in tropical trees. Biotropica. 1983;15:8–89. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert R. Soil and stem water storage determine phenology and distribution of tropical dry forest trees. Ecology. 1994;75:1437–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Bunker DE, Carson WP. Drought stress and tropical forest woody seedlings: effect on community structure and composition. Journal of Ecology. 2005;93:794–806. [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann C, Grumbach K. Physiologie der Photosynthese. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves MM, Maroco JP, Pereira JS. Understanding plant responses to drought – from genes to the whole plant. Functional Plant Biology. 2003;30:239–264. doi: 10.1071/FP02076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elcan JM, Pezeshki SR. Effects of flooding on susceptibility of Taxodium distichum L. seedlings to drought. Photosynthetica. 2002;40:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht BMJ, Kursar TA. Comparative drought resistance of seedlings of 28 woody species of co-occurring tropical woody plants. Oecologia. 2003;136:383–393. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht BMJ, Kursar TA, Tyree MT. Drought effects on seedling survival in a tropical moist forest. Trees. 2005;19:312–321. [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht BMJ, Comita LS, Condit R, et al. Drought sensitivity shapes species distribution patterns in tropical forests. Nature. 2007;447:80–82. doi: 10.1038/nature05747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Corrêa AF, Furch B. Investigations on the tolerance of several trees to submergence in blackwater (Igapó) and whitewater (Várzea) inundation forests near Manaus, Central Amazonia. Amazoniana. 1992;12:71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira LV. Effects of flooding duration on species richness, floristic composition and forest structure in river margin habitat in Amazonian blackwater floodplain forests: implications for future design of protected areas. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2000;9:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Frailey CD, Rancy Lavina A, Souza Filho JP. A proposed Pleistocene/Holocene lake in the Amazon basin and its significance to Amazonian geology and biogeography. Acta Amazonica. 1988;18:119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gutschick VP, BassiriRad H. Extreme events as shaping physiology, ecology, and evolution of plants: toward a unified definition and evaluation of their consequences. New Phytologist. 2003;160:21–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horna JV. Carbon release from woody parts of trees from a seasonally flooded Amazon forest near Manaus, Brazil. 2002 Bayreuther Forum Ökologie: Bayreuther Institut für Terrestrische Ökosystemforschung (BITÖK) [Google Scholar]

- Horna V, Zimmermann R, Müller E, Parolin P. Sap flux and stem respiration. In: Junk WJ, Piedade MTF, Parolin P, Wittmann F, Schöngart J, editors. Central Amazonian floodplain forests: ecophysiology, biodiversity and sustainable management. Ecological Studies. Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme M, Viner D. A climate change scenario for the tropics. Climatic Change. 1998;39:145–176. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change AR4 Synthesis report, IPCC Secretariat, Geneva, Switzerland. 2007. http://www.ipcc.ch/

- Irion G, Junk WJ, Mello JASN. The large central Amazonian river floodplains near Manaus: geological, climatological, hydrological and geomorphological aspects. In: Junk WJ, editor. The Central Amazon floodplain: ecology of a pulsing system. Ecological Studies 126. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 1997. pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Junk WJ. Flood tolerance and tree distribution in Central Amazonian floodplains. In: Nielsen LB, Nielsen IC, Balslev H, editors. Tropical forests: botanical dynamics, speciation and diversity. London: Academic Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Junk WJ, Krambeck H-J. Climate and hydrology. In: Junk WJ, Ohly JJ, Piedade MTF, Soares MGM, editors. The Central Amazon floodplain: actual use and options for a sustainable management. Leiden: Backhuys Publishers; 2000. pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Junk WJ, Bayley PB, Sparks RE. The flood pulse concept in river-floodplain systems. In: Dodge DP, editor. Proceedings of the International Large River Symposium (LARS) Canada: Canadian Special Publication of Fisheries Aquatic Sciences, Ottawa; 1989. pp. 110–127. [Google Scholar]

- Keel SHK, Prance GT. Studies of the vegetation of a white-sand black-water igapó (Rio Negro, Brazil) Acta Amazonica. 1979;9:645–655. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski TT, Pallardy SG. Acclimation and adaptive responses of woody plants to environmental stresses. The Botanical Review. 2002;68:270–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kreibich H. Forschungsbericht Agrartechnik. 2002. N2 fixation and denitrification in a floodplain forest in Central Amazonia, Brazil. 398. [Google Scholar]

- Kubitzki K. The ecogeographical differentiation of Amazonian inundation forests. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1989;162:285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Larcher W. Ökophysiologie der Pflanzen: Leben, Leistung und Streßbewältigung der Pflanzen in ihrer Umwelt. 6. Aufl. Stuttgart: Ulmer, UTB für Wissenschaft; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler HK. Csermely P, editor. The stress concept in plants: an introduction. Stress of life: from molecules to man. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;851:187–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OR, Kursar TA. Does flood tolerance explain tree species distribution in tropical seasonally flooded habitats? Oecologia. 2003;136:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OR, Kursar TA. Interannual variation in rainfall, drought stress and seedling mortality may mediate monodominance in tropical flooded forests. Oecologia. 2007;154:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s00442-007-0821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia LA, Piedade MTF. Influence of the flood pulse on leaf phenology and photosynthetic activity of trees in a flooded forest in Central Amazonia/Brazil. Amazoniana. 2002;17:53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Marengo JA, Nobre CA. General characteristics and variability of climate in the Amazon basin and its links to the global climate system. In: McClain ME, Victoria RL, Richey LE, editors. The biogeochemistry of the Amazon basin. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Marengo JA, Nobre CA, Tomasella J, et al. The drought of Amazonia in 2005. Journal of Climate. 2008;21:495–516. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinho TAS. Distribuição e estrutura da população de quatro espécies madeireiras em uma floresta sazonalmente alagável na Reserva de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Mamirauá, Amazônia Central. 2008 Master Thesis in Biological Sciences, Instituto Nacional de pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus. [Google Scholar]

- Medina E. Adaptations of tropical trees to moisture stress. In: Golley FB, editor. Ecosystems of the world: tropical rain forest ecosystems. Amsterdam: Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co; 1983. pp. 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer U. Feinwurzelsysteme und Mykorrhizatypen als Anpassungsmechanismen in Zentralamazonischen Überschwemmungswäldern – Igapó und Várzea. University of Hohenheim; 1991. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Müller E. In: Water relations and stem water usage of trees from the Central Amazonian whitewater floodplain (Várzea) Lieberei R, Bianchi H-K, Boehm V, Reissdorff C, editors. 2002. pp. 623–627. Proceedings of the German-Brazilian Workshop Hamburg 2000. GKSS Geesthacht. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PM. Coping mechanisms for crop plants in drought-prone environments. Annals of Botany. 2008;101:901–907. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira AA, Mori SA. A central Amazonian terra firme forest. I. High tree species richness on poor soils. Biodiversity and Conservation. 1999;8:1219–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira LA, Moreira FW, Falcão NP, Pinto VSG. Floodplain soils of Central Amazonia: chemical and physical characteristics and agricultural sustainability. In: Junk WJ, Ohly JJ, Piedade MTF, Soares MGM, editors. The Central Amazon floodplain: actual use and options for a sustainable management. Leiden: Bachhuys Publ; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Wittmann A. Conteúdo de tococromanóis em espécies arbóreas de várzea da Amazônia Central Manaus, Brazil. 2006 PhD Thesis, INPA/UFAM. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Wittmann A, Piedade MTF, Wittmann F, Parolin P. Germination in four low-várzea tree species of Central Amazonia. Aquatic Botany. 2007;86:197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Wittmann A, Lopes A, Conserva AS, Wittmann F, Piedade MTF. Seed germination and seedling establishment of Amazonian floodplain trees. In: Junk WJ, Piedade MTF, Parolin P, Wittmann F, Schöngart J, editors. Central Amazonian floodplain forests: ecophysiology, biodiversity and sustainable management. Ecological Studies. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2009. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Parolin P. Phenology and CO2-assimilation of trees in Central Amazonian floodplains. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 2000;16:465–473. [Google Scholar]

- Parolin P. Morphological and physiological adjustments to waterlogging and drought in seedlings of Amazonian floodplain trees. Oecologia. 2001;128:326–335. doi: 10.1007/s004420100660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolin P. Submerged in darkness: adaptations to prolonged submergence by woody species of the Amazonian floodplains. Annals of Botany. 2009;103:359–376. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolin P, De Simone O, Haase K, Waldhoff D, Rottenberger S, Kuhn U. Central Amazon floodplain forests: tree survival in a pulsing system. The Botanical Review. 2004;70:357–380. [Google Scholar]

- Parolin P, Müller E, Junk WJ. Water relations of Amazonian Várzea trees. International Journal of Ecology and Environmental Sciences. 2005;31:361–364. [Google Scholar]

- Parolin P, Waldhoff D, Piedade MTF. Fruit and seed chemistry, biomass and dispersal. In: Junk WJ, Piedade MTF, Parolin P, Wittmann F, Schöngart J, editors. Central Amazonian floodplain forests: ecophysiology, biodiversity and sustainable management. Ecological Studies. Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Pires JM. The Amazonian forest. In: Sioli H, editor. The Amazon: limnology and landscape ecology of a mighty tropical river and its basin. Dordrecht: Junk; 1984. pp. 581–602. [Google Scholar]

- Poorter L, Markesteijn L. Seedling traits determine drought tolerance of tropical tree species. Biotropica. 2008;40:321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Prance GT. Notes on the vegetation of Amazonia. III. Terminology of Amazonian forest types subjected to inundation. Brittonia. 1979;31:26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn WH, Neal VT. The historical record of El Niño events. In: Bradley RS, Jones PD, editors. Climate A.D. 1500. London: Routledge; 1992. pp. 623–648. [Google Scholar]

- Quiring SM. Developing objective operational definitions for monitoring drought. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. 2009;48:1217–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Reich PB, Ellsworth DS, Walters MB, et al. Generality of leaf trait relationships: a test across six biomes. Ecology. 1999;80:1955–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Roosevelt AC. Parmana: prehistoric maize and manioc subsistence along the Amazon and Orinoco. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Roth I. Stratification of tropical forests as seen in leaf structure. The Hague: Junk Publishers; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter U-B. Morphologische, anatomische und physiologische Untersuchungen zur Überflutungstoleranz zweier charakteristischer Baumarten des Weiß- und Schwarzwasser Überschwemmungswaldes bei Manaus. Ein Beitrag zur Ökosystemanalyse von Várzea und Igapó Zentralamazoniens. 1989. Dissertation, Universität Kiel. [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter U-B, Furch B. Morphologische, anatomische und physiologische Untersuchungen zur Überflutungstoleranz des Baumes Macrolobium acaciaefolium, charakteristisch für die Weiß- und Schwarzwasserüberschwemmungswälder bei Manaus, Amazonas. Amazoniana. 1992;12:51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Schöngart J, Junk WJ. Forecasting the flood pulse in Central Amazonia by ENSO-indices. Journal of Hydrology. 2007;335:124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Schöngart J, Junk WJ, Piedade MTF, Ayres JM, Hüttermann A, Worbes M. Teleconnection between tree growth in the Amazonian floodplains and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation Effect. Global Change Biology. 2004;10:683–692. [Google Scholar]

- Sestak Z. Photosynthesis during leaf development. Dordrecht: Junk; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sombroek W. Spatial and temporal patterns of Amazonian rainfall: consequences for the planning of agricultural occupation and the protection of primary forests. Ambio. 2001;30:388–396. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-30.7.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg H. Aggravation of floods in the Amazon River as a consequence of deforestation? Geografiska Annaler Series A. 1987;69:201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Stroh CL, De Steven D, Guntenspergen GR. Effect of climate fluctuations on long-term vegetation dynamics in Carolina Bay wetlands. Wetlands. 2008;28:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- ter Steege H. Flooding and drought tolerance in seeds and seedlings of 2 mora species segregated along a soil hydrological gradient in the tropical rain-forest of Guyana. Oecologia. 1994;100:356–367. doi: 10.1007/BF00317856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournaire-Roux C, Sutka M, Javot H, et al. Cytosolic pH regulates root water transport during anoxic stress through gating of aquaporins. Nature. 2003;425:393–397. doi: 10.1038/nature01853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomisto H, Ruokolainen K, Salo J, Lago Amazonas: fact or fancy? Acta Amazonica. 1992;22:353–361. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hammen T. The Pleistocene changes of vegetation and climate in tropical South America. Journal of Biogeography. 1974;1:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier BS. Pleistocene changes in the fauna and flora of South America. Science. 1971;173:771–779. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3999.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldhoff D. Leaf structure in trees of Central Amazonian floodplain forests (Brazil) Amazoniana. 2003;17:451–469. [Google Scholar]

- Waldhoff D, Furch B. Leaf morphology and anatomy in eleven tree species from Central Amazonian floodplains (Brazil) Amazoniana. 2002;17:79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Waldhoff D, Junk WJ, Furch B. Responses of three Amazonian tree species to drought and flooding under controlled conditions. International Journal of Ecology and Environmental Sciences. 1998;24:237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Waldhoff D, Junk WJ, Furch B. Comparative measurements of growth and chlorophyll a fluorescence parameters of Nectandra amazonum under different environmental conditions in climatized chambers. Verhandlungen des Internationalen Vereineins für Limnologie. 2000;27:2052–2056. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh RPD, Newberry DM. The ecoclimatology of Danum, Sabah, in the context of the world's rainforest regions, with particular reference to dry periods and their impact. Physiological Transactions of the Royal Society London, Series B. 1999;354:1391–1400. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E, Dall'Antonia A, Dall'Antonia V, Almeida FS, Liebmann B, Malhado A. The drought of the century in the Amazon basin: an analysis of the regional variation of rainfall in South America in 1926. Acta Amazonica. 2005;35:231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann F, Junk WJ. Sapling communities in Amazonian white-water forests. Journal of Biogeography. 2003;30:1533–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann F, Parolin P. Aboveground roots in Amazonian floodplain trees. Biotropica. 2005;37:609–619. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann F, Anhuf D, Junk WJ. Tree species distribution and community structure of Central Amazonian várzea forests by remote sensing techniques. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 2002;18:805–820. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann F, Junk WJ, Piedade MTF. The várzea forests in Amazonia: flooding and the highly dynamic geomorphology interact with natural forest succession. Forest Ecology and Management. 2004;196:199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann F, Schöngart J, Montero JC, et al. Tree species composition and diversity gradients in white-water forests across the Amazon basin. Journal of Biogeography. 2006;33:1334–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann F, Junk WJ, Schöngart J. Phytogeography, species diversity, community structure and dynamics of central Amazonian floodplain forests. In: Junk WJ, Piedade MTF, Parolin P, Wittmann F, Schöngart J, editors. Central Amazonian floodplain forests: ecophysiology, biodiversity and sustainable management. Ecological Studies. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2009. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Worbes M. Lebensbedingungen und Holzwachstum in zentralamazonischen Überschwemmungswäldern. Scripta Geobotanica. 1986;17:1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Worbes M. The forest ecosystem of the floodplains. In: Junk WJ, editor. The Central Amazon floodplain: ecology of a pulsing system. Ecological Studies 126. Heidelberg: Springer; 1997. pp. 223–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wright SJ, Cornejo FH. Seasonal drought and the timing of flowering and leaf fall in a neotropical forest. In: Bawa KS, Hadley M, editors. Reproductive ecology of tropical forest plants, Vol. 7. Man and the Biosphere Series. Paris: UNESCO; 1990. pp. 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ziburski A. Ausbreitungs- und Reproduktionsbiologie einiger Baumarten der amazonischen Überschwemmungswälder. University of Hamburg; 1990. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]