Abstract

The lytic phage phiL7, which morphologically belongs to the Siphoviridae family, infects Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Nucleotide sequence analysis has revealed that phiL7 contains a linear double-stranded DNA genome (44,080 bp, 56% G+C) with a 3′-protruding cos site (5′-TTACCGGAC-3′) and 59 possible genes. Among the deduced proteins, 32 have homologs with known functions and 18 show no database similarities; moreover, the genes encoding these 18 proteins mostly have varying G+C contents and form clusters dispersed along the genome. Only 39 genes have sequences related (27% to 78%) to those of sequenced genes of X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages, although the genome size and architecture of these Xanthomonas phages are similar. These findings suggest that phiL7 acquired genes by horizontal transfer, followed by evolution via various types of mutations. Major differences were found between phiL7 and the X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages: (i) phiL7 has a group I intron inserted in the DNA polymerase gene, the first such intron observed in Xanthomonas phages; (ii) although infection of phiL7 exerted inhibition to the host RNA polymerase, similar to the situations in X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages Xp10 and Xop411, sequence analysis did not identify a homologue of the Xp10 p7 that controls the shift from host RNA polymerase (RNAP) to viral RNAP during transcription; and (iii) phiL7 lacks the tail fiber protein gene that exhibits domain duplications thought to be important for host range determination in OP1, and sequence analysis suggested that p20 (tail protein III) instead has the potential to play this role.

The genus Xanthomonas in the gamma subdivision of the Proteobacteria is a diverse and economically important group of bacterial plant pathogens consisting of 27 species (35), causing tremendous loss in agriculture worldwide. Individual species of this genus comprise multiple pathogenic variants (pathovars) and collectively cause diseases on at least 124 monocot species and 268 dicot species: for example, Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris causes black rot in crucifers, X. campestris pv. vesicatoria causes spot disease in peppers and tomatoes, X. axonopodis pv. citri causes citrus canker, and X. oryzae pv. oryzae causes bacterial leaf blight on rice plants (17). In addition, members of the genus Xanthomonas commonly produce great amounts of an exopolysaccharide (xanthan gum) and X. campestris pv. campestris has been the organism of choice in industry for production of xanthan, which is useful in food, agriculture, industry and cosmetics (55).

For controlling bacterial plant diseases, chemical control with antibiotics and copper compounds has been the standard (31, 46). However, many agrochemicals are toxic and may pose significant environmental and health risks (14). Therefore, there has been a resurgence of interest recently in using bacteriophages to replace the currently prevalent chemical measures, in which phages can be used effectively as part of integrated disease management strategies (12, 15, 16, 32). Although phage contamination has not been reported to cause problems in xanthan production (42), a number of Xanthomonas bacteriophages have been documented and some of them tested to show effectiveness to some extent in the control of plant diseases caused by Xanthomonas. As summarized in the review by Jones et al. (22), these included bacterial spots in the genus Prunus, bacterial leaf blight on rice plants, tomato bacterial spots, bacterial blight of geraniums, bacterial blight on onions, citrus bacterial canker, and citrus bacterial spots. Encouragingly, at least one of the efforts has been fruitful, and a mixture of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria phages against tomato bacterial spots (Agriphage from OmniLytics, Inc.) is at present commercially available (22).

In addition to the efforts in biocontrol, some Xanthomonas phages have been characterized by genomic sequencing, including the X. oryzae pv. oryzae Siphoviridae phages Xop411, Xp10, and OP1; the X. oryzae pv. oryzae Caudoviridae phage OP2 (20, 21, 24, 56); and the X. campestris pv. pelargonii Caudoviridae phage Xp15 (accession no. AY986977). Furthermore, filamentous phages each specifically infecting but not lysing X. campestris pv. campestris, X. oryzae pv. oryzae, X. axonopodis pv. citri, and X. campestris pv. vesicatoria have been reported (23, 28, 29, 50). In X. campestris pv. campestris, although biocontrol testing was not reported, several phages that can lyse X. campestris pv. campestris have been described. First, two temperate phages were isolated in the continental United States (44, 52). Second, three, seven, and three lytic phages were isolated in Japan, Hawaii, and the continental United States, respectively (27, 43, 51). They fall in groups A, B, and C of Bradley's classification (27), likely belonging to Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, and Podoviridae, respectively. Third, the lytic phage phiL7 was isolated in Taiwan (40). This phage has been described as “tadpole-shaped” in morphology and has been shown to (i) infect 33 Taiwan isolates of X. campestris pv. campestris but not X. axonopodis pv. citri, X. oryzae pv. oryzae, and X. axonopodis pv. phaseoli; (ii) cause complete lysis of the host in liquid cultures; (iii) form plaques of 2 to 3 mm in diameter on LB agar plates; (iv) contain a double-stranded genomic DNA susceptible to digestion with restriction endonucleases (40); and (v) require the lipopolysaccharide and the tonB gene cluster of the host for the initial steps of infection (18, 19).

Prior to application of phages in biocontrol, it is important to exclude temperate phages and to understand their genetics, host interactions (being capable of rapid infection and lysis of the host), stability, and host range. Genome sequencing is useful to verify the absence of genes associated with lysogenization. In addition, sequence data are important for phage classification and in understanding the evolution of these phages. In this study, sequence was determined for the phiL7 genome and no genes associated with lysogenization were found. Results of sequence comparison indicate that phiL7 is similar to the X. oryzae pv. oryzae siphophages Xop411, Xp10, and OP1 (20, 24, 56) in genome organization and having its own single-subunit RNA polymerase (RNAP), characteristic of T7-like phages of the Podoviridae family, but it differs in possessing a group I intron inserted in the DNA polymerase gene. Other important differences were also found and are discussed in this paper.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, phage, and conditions of cultivation.

X. campestris pv. campestris strain 17 (54) was used as the host for phage propagation and titer determination. Phage phiL7 was isolated in our laboratory as described previously (14). Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strain 21 and its lytic phage Xop411 have been described previously (24, 25). Strains of Xanthomonas and Escherichia coli were grown at 28°C and 37°C, respectively, in TYG (tryptone, 10 g; yeast extract, 6 g; 1 ml of 1 M MgSO4; 25 ml of 20% [wt/vol] glucose in deionized H2O to a final volume of 1 liter). Phage propagation, plaque assay, purification of phage particles, isolation of phage DNA, and restriction digestion were performed as described previously (24, 25).

Purification of phage.

Cells of X. campestris pv. campestris strain 17 from an overnight culture were diluted into the fresh medium (20 ml) and grown to an optical density at 550 nm (OD550) of 1.8. Phage phiL7 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5.0 was added to the culture. After complete lysis (about 5 h), the lysate (5.0 × 1010 PFU/ml) was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to remove the cell debris, followed by filtering the supernatant through a 0.45-μm filter membrane and centrifugation at 19,000 rpm (rotor JA-25.50 in Beckman-Coulter J-25) at 4°C for 3 h. The pelleted phage particles were suspended in 1.0 ml of deionized water and loaded onto a discontinuous density gradient containing 1.3, 1.45, 1.5, and 1.7 g/ml of cesium chloride and subjected to ultracentrifugation at 30,000 rpm (SW41 Ti rotor in a Beckman-Coulter LE-80K) at 4°C for 3 h. The banded phage particles were dialyzed against 4 liters of deionized water with two changes of the water.

Electron microscopy.

Phage phiL7 was examined by electron microscopy of negatively stained preparations. A drop of the sample containing the phage particles purified by ultracentrifugation was applied to the surface of a Formvar-coated grid (200 mesh copper grids), negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate, and examined in a Hitachi/H-7500 transmission electron microscope operated at 80 kV (Electron Microscopy Laboratory, Tzu Chi University).

DNA sequencing and bioinformatics.

Previously described procedures (24) were used to purify and shear the phage DNA, clone the DNA fragments into pBluescript II SK, and determine the nucleotide sequence (including the genome ends). The sequences obtained were analyzed with Vector NTI software (InforMax). Various programs were used for search and prediction: SignalP V2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk) for signal sequences (verified manually to confirm the presence of N, C, and H regions), BLASTP (1) for similarities (using an e value lower than e−4 as a cutoff for notable similarity) and conserved domains, InterProScan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/scan.html) for motifs, TMHMM 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/) for transmembrane domains, Geecee from EMBOSS (http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/seqanal/interfaces/geecee.html) for G+C content, and the program posted at http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html for promoters. HNH endonucleases were identified by searching for conserved domains as well as similarities to the endonucleases identified in Xp10 and Xop411 (24).

SDS-PAGE and LC-MS/MS analysis.

Phage particles purified by ultracentrifugation were mixed with sample buffer, heated in a boiling water bath for 3 min, and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) separation in 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel. Protein bands were visualized by staining the gels with Coomassie brilliant blue, excised from the gels, and subjected to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (ABI Qstar System) analysis at the Biotechnology Center, National Chung Hsing University.

Splicing assay.

An overnight culture of X. campestris pv. campestris strain 17 (3 ml) was transferred into 25 ml of fresh 2× TYG medium, grown for 2 h (OD550 of 0.8), and infected with phiL7 at an MOI of 10. At 30 min postinfection, 1 ml of the culture was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 1 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed once with 1 ml of killing buffer (280 mg NaN3, 80 mg chloramphenicol in 2× TYG medium, to a final volume of 100 ml), and cells were immediately stored at −70°C until used. Total RNA was extracted using Tri-zon (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples were checked by formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified by measuring the A260/A280 ratio. Two micrograms of total RNA (10 min postinfection with an MOI of 10) was incubated with 75 ng of random primers, followed by first-strand cDNA synthesis using a SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen). The resultant cDNA was purified, diluted appropriately, and used for PCR amplification and subsequent cycle sequencing employing the primers P41R (5′-TTACTCCTGTTCAAATGTGGGTGTG-3′) and P46F (5′-ATGAGCTACGTTGTGCTAGACCTT-3′) and the internal primers P44R (5′-TTACTCCTGTTCAAATGTGGGTGTG-3′) and P44F (5′-GTGTCTAGGTTCTCCGGC-3′). PCR was initiated with a hot start (5 min), followed by 30 cycles of reactions, each of which included denaturation at 94°C (30 s), annealing at 57°C (30 s), and elongation at 72°C (3 min), followed by final extension (7 min). The amplicons were separately ligated into the PCR cloning vector yT&A vector (Yeastern Biotech) and sequenced.

RNAP activity assay.

Crude extracts were prepared for the RNAP assay as described by Liao and Kuo (26), except that the buffer described in Cheng et al. (10) was used (designated as RPA [RNase protection assay] buffer herein). Two cultures (100 ml) of X. campestris pv. campestris strain 17 were grown in TYG medium until the OD550 was 2.0. One culture was infected with phiL7 at an MOI of 10, leaving the other as an uninfected control. After further incubation for 35 min, both cultures were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min) at 4°C and the pelleted cells were immediately kept at −80°C for 10 min. The cells were suspended in 5 ml of the RPA buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, containing 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM dithiothreitol) and disrupted by passing through a French press (1,000 lb/in2, four times). After centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C), the supernatants were passed through a 0.22-μm-pore membrane filter. As positive controls, crude extracts were prepared in parallel from cells of X. oryzae pv. oryzae strain 21 infected or uninfected with phage Xop411.

The activity of RNAP was assayed as described by Cheng et al. (10) with some modifications. The reaction mixture (60 μl) contained the RPA buffer, 0.9 μg of either host or phage DNA template, 0.5 mM nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs), 5 μCi [α-32P]UTP, and 250 μg protein from the crude extracts. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and terminated by addition of 1 ml of cold 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The labeled RNA products were collected by a filter (Whatman GF/A). Each filter was washed three times with 1 ml of cold TCA (5%), then 1 ml of cold ethanol. The filters were air dried, and activity was counted with a liquid scintillation counter (Tri-Carb 2900TR; Packard).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete nucleotide sequence of phage phiL7 has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. EU717894.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

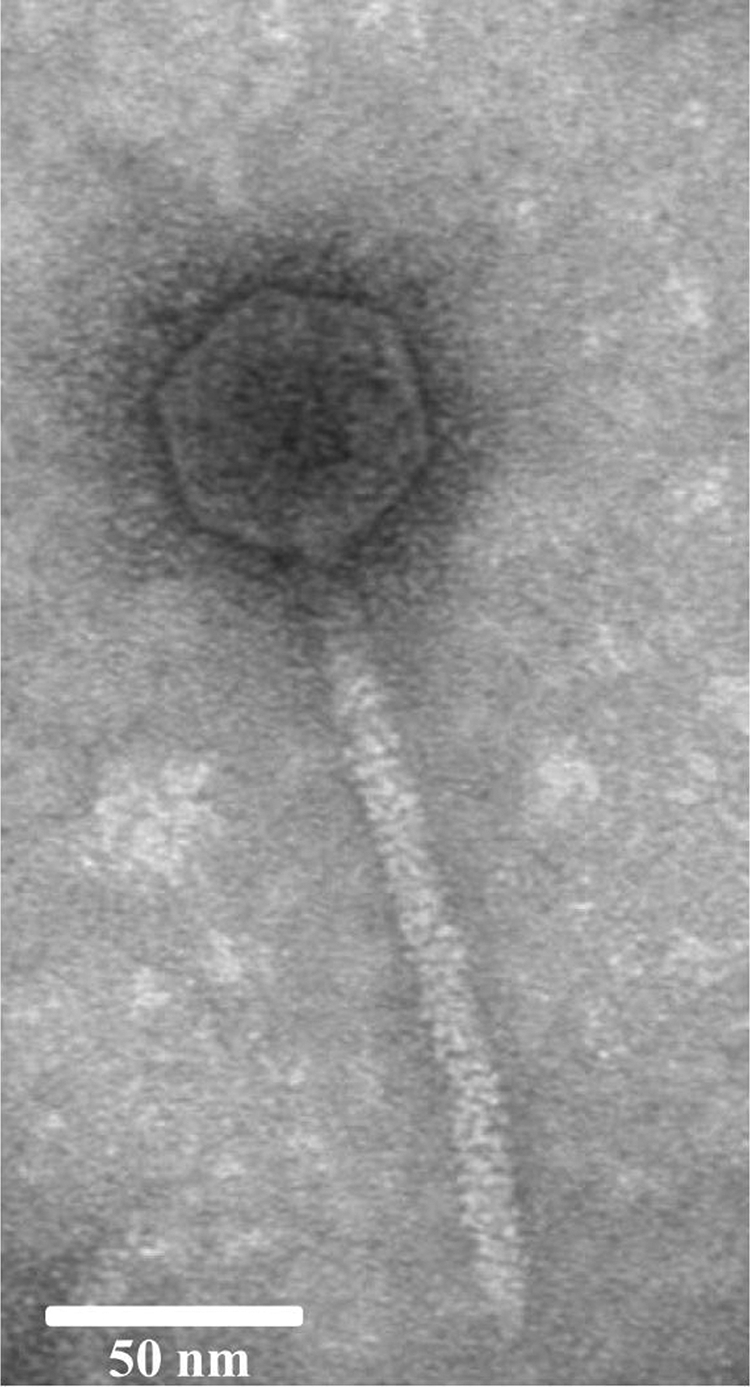

Phage phiL7 morphologically belongs to the family Siphoviridae.

To describe the phage morphology, the particles of phiL7 were examined by transmission electron microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1, phiL7 had an icosahedral capsid and a long noncontractile tail. Fourteen images of the phage were measured, and the mean values were as follows: the head was 53.2 ± 4.0 nm in diameter, while the tail was 156.2 ± 5.1 nm long by 10 ± 0.8 nm wide. Based on morphology, phiL7 belonged to the family Siphoviridae, similar to the X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages Xp10, Xop411, and OP1, which encode their own single-subunit RNAP characteristic of T7-like phages of the family Podoviridae (20, 24, 56).

FIG. 1.

Electron microscopic appearance of phage phiL7. It has an icosahedral capsid and a long tail. Bar, 50 nm.

Only 39 of the 59 deduced phiL7 proteins share similarities with proteins from X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages.

Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed some important features of the phiL7 genome. We found that phiL7 contained a linear, double-stranded DNA (44,080 bp) with a G+C content of 56%, different from that of the host genome (ca. 65%; accession no. NC_003902). In addition, the phiL7 genome, having a 9-nucleotide (nt) 3′-protruding cos site (5′-TTACCGGAC-3′) at either end, was similar to the Xop411 and Xp10 genomes in genome organization (24, 56). We also observed many repeated sequences dispersed throughout the phiL7 genome, with the longest being a 22-bp direct repeat (5′-GCCACCTCGTTAGCTTGTTGGG-3′; nt 23605 to 23626 and 23627 to 23648), located at the 3′ end of p31 and immediately downstream; the second longest repeated sequence was a 19-bp direct repeat (5′-ATAGAGCCTACATCGCCCT-3′; nt 42364 to 42382 and 42454 to 42472) in the p56/p57 intergenic region. Furthermore, we observed a stretch of AT-rich sequence (85% A+T; nt 43049 to 43188) similar to that at the corresponding regions of the X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages Xop411, Xp10, and OP1 (24). This AT-rich region contained six pairs of direct repeats with 8 or more nt (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), resembling the ori (origin for replication) regions of some phages with repeated sequences, termed “iterons” and “AT-rich zones.” For example, the lambdoid phages have three to five iterons (33, 48).

With ATG or GTG as the initiation codon, a possible ribosomal binding site in the upstream region, and each putative open reading frame (ORF) containing more than 50 amino acid residues, we assigned 59 ORFs to phiL7. The genome was divided into left and right arms by the p56/p57 intergenic region, with genes of the two arms transcribed convergently (Fig. 2). The 59 deduced proteins included (i) 32 that had database homologs of known function, including HNH endonucleases, DNA packaging proteins, viral structures, and proteins involved in replication, transcription, and lysis; (ii) 9 hypothetical proteins; and (iii) 18 proteins with no similarities in the database (Table 1). We found that several of the 18 unknown genes (p01, p25, p33, p54, p55, and p57) possessed G+C contents that deviated from the average content of the genome (56%) (Table 1), suggesting that they had been acquired by horizontal gene transfer. We also found that only 39 of the 59 deduced proteins showed similarities (27% to 78%) to proteins of the X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages, despite correlations in genome size, architecture, and amino acid sequence. Furthermore, we determined that six proteins (p13, p14, p24, p29, p29.1, and p53) were unique to the four Xanthomonas phages. In contrast, most of the proteins from p23 to p48, in addition to being similar to those of the X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages, shared high degrees of relationship with proteins from Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1 (NC_011201) and Burkholderia pseudomallei 1710b (NC_007435). We also found that p15 encoded a hypothetical protein similar to ORF16 of OP1, but not to any ORF of Xp10 and Xop411, that p45 was 46% identical only to ORF13 (YP_001285778) of Leptolyngbya foveolarum phage Pf-WMP3, and that p32 showed 60% identity only to SSKA14_4204 (YP_002706785) of Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SKA14 (Table 2). Taken together, these results indicate that phiL7 may have the same ancestor as, or may have exchanged genes with, the R. solanacearum phage RSB1 and B. pseudomallei 1710b and that horizontal gene transfer and numerous recombination and mutation events must have occurred to give rise to phiL7. Finally, our sequence analysis revealed no phiL7 genes that are potentially associated with lysogenization.

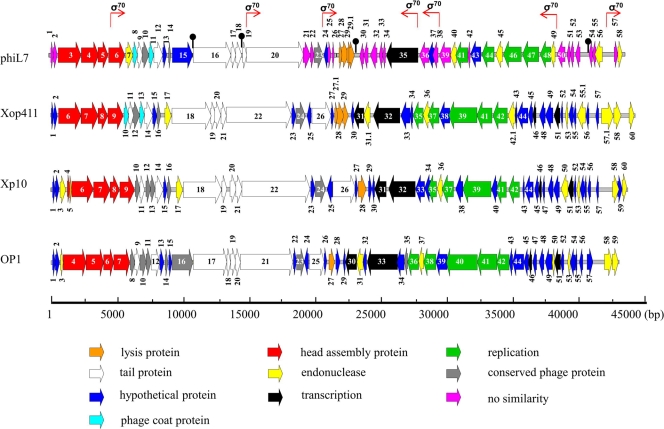

FIG. 2.

Genome organization of phages phiL7, Xop411, Xp10, and OP1. Colored arrows indicate the directions and categories of the genes (denoted below). The numbers inside or near the arrows are gene designations. The σ70-type promoter is shown, and the black knob shows the position of a terminator predicted in phiL7.

TABLE 1.

Assignment of phiL7 genes

| Gene | Strand | Start | Stop | G+C (%) | Length (aa) | Mass (kDa) | pI | Comment(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p01 | + | 117 (ATG) | 335 (TGA) | 69 | 72 | 7.5 | 10.4 | No similarity |

| p02 | + | 430 (ATG) | 633 (TAA) | 52 | 101 | 10.7 | 9.5 | Hypothetical protein |

| p03 | + | 670 (ATG) | 2361 (TAA) | 54 | 563 | 61.3 | 5.8 | Terminase large subunit |

| p04 | + | 2371 (ATG) | 3663 (TGA) | 55 | 430 | 46.4 | 9.0 | Head portal protein |

| p05 | + | 3660 (ATG) | 4397 (TAA) | 55 | 245 | 25.9 | 4.9 | Protease of the ClpP family |

| p06 | + | 4402 (ATG) | 5586 (TAA) | 59 | 394 | 41.6 | 5.3 | Major head protein |

| p07 | + | 5677 (ATG) | 6198 (TGA) | 52 | 173 | 19.9 | 9.6 | HNH endonuclease |

| p08 | + | 6195 (ATG) | 6536 (TAA) | 54 | 113 | 12.7 | 5.3 | Phage coat protein I |

| p09 | + | 6536 (ATG) | 6910 (TAG) | 56 | 124 | 13.0 | 5.6 | Head-tail joining |

| p10 | + | 6918 (ATG) | 7385 (TGA) | 54 | 155 | 16.9 | 10.2 | Conserved phage protein I |

| p11 | + | 7382 (ATG) | 7735 (TAA) | 58 | 117 | 12.9 | 4.7 | Phage coat protein II |

| p12 | + | 7751 (ATG) | 8395 (TAA) | 57 | 214 | 22.5 | 5.1 | Major tail |

| p13 | + | 8395 (ATG) | 8697 (TAA) | 53 | 100 | 10.9 | 5.6 | Hypothetical protein |

| p14 | + | 8835 (ATG) | 9008 (TAG) | 54 | 57 | 6.4 | 5.7 | Conserved phage protein II |

| p15 | + | 9100 (GTG) | 10611 (TAA) | 51 | 503 | 56.8 | 9.4 | Hypothetical protein |

| p16 | + | 10660 (ATG) | 13581 (TAA) | 57 | 973 | 101.3 | 7.6 | Tail length tape measure protein |

| p17 | + | 13581 (ATG) | 13940 (TGA) | 49 | 119 | 13.8 | 6.6 | Tail protein I |

| p18 | + | 13937 (ATG) | 14398 (TGA) | 54 | 153 | 17.2 | 4.6 | Tail protein II |

| p19 | + | 14467 (GTG) | 14787 (TAG) | 51 | 106 | 12.3 | 6.6 | Hydrolase, tail protein |

| p20 | + | 14772 (ATG) | 19199 (TGA) | 56 | 1475 | 157.7 | 4.9 | Tail protein III |

| p21 | + | 19210 (ATG) | 19710 (TAA) | 58 | 166 | 17.5 | 4.3 | No similarity |

| p22 | + | 19710 (ATG) | 20009 (TGA) | 57 | 99 | 10.5 | 6.5 | Hypothetical protein |

| p23 | + | 20009 (ATG) | 20692 (TAG) | 57 | 227 | 24.1 | 8.8 | Conserved phage protein III |

| p24 | − | 21060 (ATG) | 20689 (TAA) | 57 | 123 | 13.4 | 6.9 | Hypothetical protein |

| p25 | + | 21081 (GTG) | 21338 (TGA) | 61 | 85 | 8.5 | 9.7 | No similarity |

| p26 | + | 21424 (GTG) | 21588 (TAA) | 57 | 54 | 5.9 | 12.1 | No similarity |

| p27 | + | 21738 (ATG) | 21956 (TAA) | 53 | 72 | 7.9 | 10.6 | No similarity (putative holin) |

| p28 | + | 21931 (ATG) | 22455 (TAA) | 57 | 174 | 18.9 | 9.5 | Phage-type lysozyme |

| p29 | + | 22439 (ATG) | 22756 (TAA) | 53 | 105 | 15.1 | 9.8 | Putative Rz |

| p29.1 | + | 22641 (ATG) | 22943 (TAG) | 58 | 100 | 11.1 | 8.5 | Putative Rz1 |

| p30 | − | 23500 (ATG) | 23312 (TAG) | 58 | 62 | 6.3 | 9.8 | No similarity |

| p31 | − | 23931 (ATG) | 23614 (TAA) | 59 | 105 | 11.7 | 5.0 | No similarity |

| p32 | − | 24628 (ATG) | 24098 (TAA) | 60 | 176 | 19.3 | 5.4 | Hypothetical protein |

| p33 | − | 25045 (GTG) | 24794 (TGA) | 61 | 83 | 9.2 | 5.8 | No similarity |

| p34 | − | 25260 (ATG) | 25042 (TGA) | 52 | 72 | 7.7 | 4.3 | No similarity |

| p35 | − | 27740 (ATG) | 25326 (TAA) | 59 | 804 | 91.5 | 7.0 | RNAP |

| p36 | − | 28458 (ATG) | 27844 (TGA) | 55 | 204 | 26.6 | 6.4 | No similarity |

| p37 | − | 28916 (GTG) | 28494 (TAA) | 60 | 140 | 16.5 | 9.4 | Hypothetical protein |

| p38 | − | 29256 (ATG) | 28855 (TAA) | 56 | 133 | 14.5 | 4.7 | No similarity |

| p39 | − | 30208 (ATG) | 29360 (TAA) | 56 | 282 | 32.2 | 9.3 | Putative DNA polymerase III |

| p40 | − | 30593 (ATG) | 30198 (TAA) | 58 | 131 | 16.3 | 10.9 | Endonuclease VII |

| p41 | − | 31519 (ATG) | 30590 (TGA) | 58 | 309 | 34.7 | 7.8 | DNA polymerase I containing 5′→3′ exonuclease |

| p42 | − | 31686 (GTG) | 31516 (TGA) | 55 | 56 | 6.3 | 4.7 | No similarity |

| p43 | − | 32330 (GTG) | 31683 (TGA) | 58 | 215 | 29.1 | 5.5 | Hypothetical protein |

| p44 | − | 33502 (GTG) | 32510 (TAA) | 55 | 330 | 37.1 | 5.5 | DNA polymerase I containing C-terminal DNA polymerase A domain |

| p45 | − | 34161 (ATG) | 33631 (TAG) | 54 | 176 | 20.3 | 9.3 | HNH endonuclease |

| p46 | − | 35690 (ATG) | 34254 (TAA) | 57 | 478 | 52.8 | 5.8 | DNA polymerase I containing 3′→5′ exonuclease and N-terminal DNA polymerase A domains |

| p47 | − | 37104 (ATG) | 35803 (TAG) | 56 | 433 | 48.6 | 5.3 | Replicative helicase of the DnaB family |

| p48 | − | 38077 (ATG) | 37238 (TGA) | 59 | 279 | 31.1 | 9.5 | DNA primase of the DnaG family |

| p49 | − | 38423 (ATG) | 38052 (TAG) | 52 | 123 | 14.1 | 10.1 | HNH endonuclease |

| p50 | − | 39206 (ATG) | 38595 (TAG) | 57 | 203 | 23.0 | 9.7 | No similarity |

| p51 | − | 39637 (ATG) | 39389 (TGA) | 55 | 82 | 9.3 | 4.6 | No similarity |

| p52 | − | 40075 (ATG) | 39845 (TAA) | 58 | 76 | 8.4 | 10.3 | No similarity |

| p53 | − | 40450 (ATG) | 40079 (TAA) | 61 | 123 | 14.4 | 8.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| p54 | − | 41034 (GTG) | 40870 (TAA) | 60 | 54 | 6.3 | 10.4 | No similarity |

| p55 | − | 41460 (GTG) | 41164 (TGA) | 62 | 98 | 10.8 | 9.0 | No similarity |

| p56 | − | 42250 (ATG) | 41636 (TGA) | 58 | 204 | 23.1 | 9.3 | HNH endonuclease |

| p57 | + | 43199 (ATG) | 43501 (TAA) | 50 | 100 | 11.7 | 4.1 | No similarity |

| p58 | + | 43510 (ATG) | 43854 (TAG) | 52 | 114 | 13.0 | 9.5 | HNH endonuclease |

TABLE 2.

Comparison of deduced proteins of phiL7 with those of X. oryzae phages and other best-matched ORFsa

| phiL7 gene, aa length | Comparison (gene, % identity, aa length) with gene from phage: |

Best match ORF other than that from X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xop411 | Xp10 | OP1 | ||

| p01, 72 | — | — | — | — |

| p02, 101 | p02, 70, 60 | 2R, 75, 60 | ORF2, 72, 62 | — |

| p03, 563 | p06, 72, 555 | 6R, 73, 555 | ORF4, 70, 556 | Z1803 in E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 prophage CP-933N (53% identity, gi 15801274) |

| p04, 430 | p07, 63, 415 | 7R, 64, 415 | ORF5, 64, 415 | HK97 family phage protein, Daci_1632 in Delftia acidovorans SPH-1 (53% identity, gi 160897079) |

| p05, 245 | p08, 53, 241 | 8R, 53, 242 | ORF6, 53, 241 | ESA_01027 in Enterobacter sakazakii ATCC BAA-894 (50% identity, gi 156933216) |

| p06, 394 | p09, 57, 389 | 9R, 58, 389 | ORF7, 58, 389 | HK97 family phage protein, TM1040_1668 in Silicibacter sp. strain TM1040 (56% identity, 99081509) |

| p07, 173 | p17, 46, 156 | 17R, 48, 156 | ORF31, 45, 154 | YE2335 in Yersinia enterocolitica subsp. enterocolitica 8081 (44% identity, gi 123442580) |

| p55.1, 46, 154 | 51L, 48, 154 | ORF58, 47, 157 | ||

| 59L, 46, 155 | ||||

| p08, 113 | p10, 51, 114 | 10R, 50, 114 | ORF8, 49, 114 | gp7 in Burkholderia thailandensis E264 (49% identity, gi 83718052) |

| p09, 124 | p11, 54, 123 | 11R, 55, 123 | ORF9, 55, 123 | Aave_1775 in Acidovorax avenae subsp. citrulli AAC00-1 phage (36% identity, gi 120610456) |

| p10, 155 | p12, 41, 108 | 12R, 41, 108 | ORF10, 46, 139 | Phage protein, BAV1467 in Bordetella avium 197N (33% identity, gi 115422554) |

| p11, 117 | p13, 58, 117 | 13R, 60, 117 | ORF11, 61, 117 | Phage protein, BAV1468 in Bordetella avium 197N (31% identity, gi 115422555) |

| p12, 214 | p14, 41, 212 | 14R, 41, 212 | ORF12, 41, 212 | BP3369 in Bordetella pertussis Tohama I (41% identity, gi 33594257) |

| p13, 100 | p15, 66, 99 | 15R, 69, 98 | ORF13, 72, 98 | — |

| p14, 57 | p16, 56, 53 | 16R, 56, 53 | ORF14, 56, 55 | — |

| p15, 503 | — | — | ORF16, 55, 511 | Hypothetical protein VIP0039 in Salmonella phage E1 (38% identity, gi 6128891) |

| p16, 973 | p18, 49, 1024 | 18R, 49, 1024 | ORF17, 49, 1024 | Phage lambda family protein, SSKA14_183 in Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SKA14 (32% identity, gi 219718652) |

| p17, 119 | p19, 55, 118 | 19R, 55, 118 | ORF18, 55, 118 | gp20 in Xanthomonas campestris pv. pelargonii phage Xp15 (46% identity, gi 66392069), p19 in Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SKA14 (39% identity, gi 219721674) |

| p18, 153 | p20, 58, 152 | 20R, 59, 152 | ORF19, 59, 152 | p20 in Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SKA14 (51% identity, gi 219719979), gp21 in Xanthomonas campestris pv. pelargonii phage Xp15 (35% identity, gi 66392125) |

| p19, 106 | p21, 70, 106 | 21R, 70, 106 | ORF20, 71, 106 | p21 in Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SKA14 (51% identity, gi 219720634) gp22 in Xanthomonas campestris pv. pelargonii phage Xp15 (45% identity, gi 66392070) |

| p20, 1475 | p22, 46, 1610 | 22R, 47, 1604 | ORF21, 47, 1614 | p22 in Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SKA14 (44% identity, gi 219720177), gp23 in Xanthomonas campestris pv. pelargonii phage Xp15 (40% identity, gi 66392071) |

| p21, 166 | — | — | — | — |

| p22, 99 | p23, 37, 101 | 23R, 36, 104 | ORF22, 36, 101 | BMULJ_04619 in Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616 (34% identity, gi 189353378) |

| p23, 227 | p24, 29, 240 | 24R, 28, 232 | ORF23, 27, 234 | RSMK01629 in Ralstonia solanacearum MolK2 (30% identity, gi 207724110) |

| p24, 123 | p25, 74, 123 | 25R, 72, 122 | ORF24, 76, 123 | — |

| p25, 85 | — | — | — | — |

| p26, 54 | — | — | — | — |

| p27, 72 | — | — | — | — |

| p28, 174 | p28, 77, 162 | 28R, 75, 162 | ORF27, 78, 157 | gp19 in Enterobacteria phage ST104 (44% identity, gi 46358689), RSB1_gp43 in Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1 (38% identity, gi 197935896) |

| p29, 105 | p29, 45, 81 | 29R, 49, 81 | ORF28, 45, 81 | — |

| P29.1, 100 | Rz1, 56, 100 | Rz1, 55, 100 | Rz1, 62, 100 | — |

| p30, 62 | — | — | — | — |

| p31, 105 | — | — | — | — |

| p32, 176 | — | — | — | Hypothetical protein SSKA14_4204 in Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SKA14 (60% identity, gi 219722655) |

| p33, 83 | — | — | — | — |

| p34, 72 | — | — | — | — |

| p35, 804 | p32, 46, 804 | 32R, 47, 804 | ORF33, 47, 801 | RSB1_gp26 in Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1 (45% identity, gi 197935879) |

| p36, 204 | — | — | — | — |

| p37, 140 | p33, 50, 101 | 33L, 50, 101 | ORF34, 50, 101 | BBta_6571 in Bradyrhizobium sp. strain BTAi1 (50% identity, gi 148257797) |

| p38, 133 | — | — | — | — |

| p39, 282 | p35, 72, 247 | 34L, 72, 247 | ORF36, 70, 282 | 34L in Burkholderia pseudomallei 1710b (47% identity, gi 76580361), RSB1_gp22 in Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1 (43% identity, gi 197935875) |

| p40, 131 | p36, 51, 107 | 35L, 51, 107 | ORF37, 51, 107 | gp33 in Pseudomonas phage LKA1 (42% identity, gi 158345167), RSB1_gp21 in Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1 (48% identity, gi 197935874) |

| p41, 309 | p37, 43, 291 | 36L, 43, 291 | ORF38, 44, 291 | Bpse17_22231 in Burkholderia pseudomallei 1710a (45% identity, gi 161372315), RSB1_gp20 in Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1 (46% identity, gi 197935873) |

| p42, 56 | — | — | — | — |

| p43, 215 | p38, 34, 177 | 37L, 33, 129 | ORF39, 34, 176 | 37L in Burkholderia thailandensis MSMB43 (40% identity, gi 167841477), RSB1_gp19 in Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1 (29% identity, gi 197935872) |

| p44, 330 | p39, 47, 319 | 38L, 47, 319 | ORF40, 47, 319 | 38L in Burkholderia pseudomallei 91 (52% identity, gi 167821768) |

| RSB1_gp18 in Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1 (53% identity, gi 197935871) | ||||

| p45, 176 | — | — | — | PfWMP3_13 in Leptolyngbya foveolarum phage Pf-WMP3 (46% identity, gi 148747812) |

| p46, 478 | p39, 42, 478 | 38L, 42, 478 | ORF40, 42, 478 | DNA polymerase gp18 in Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1(49% identity, gi 197935871) |

| p47, 433 | p41, 37, 360 | 40L, 35, 257 | ORF41, 35, 428 | Replicative DNA helicase gp17 in Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1 (39% identity, gi |

| 39L, 41, 103 | 197935870) | |||

| p48, 279 | p42, 43, 262 | 41L, 44, 249 | ORF42, 43, 262 | Putative DNA primase gp16 in Ralstonia solanacearum phage RSB1 (43% identity, gi 197935869) |

| p49, 123 | p17, 38, 112 | 3R, 41, 113 | ORF31, 38, 112 | Daci_3200 in Delftia acidovorans SPH-1 (36% identity, gi 160898641) |

| p31.1, 46, 96 | 17R, 43, 115 | ORF58, 37, 113 | ||

| p42.1, 36, 112 | 49L, 40, 111 | |||

| p55.1, 41, 111 | 57R, 41, 106 | |||

| p57.1, 40, 90 | ||||

| p50, 203 | — | — | — | — |

| p51, 82 | — | — | — | — |

| p52, 76 | — | — | — | — |

| p53, 123 | p45, 38, 95 | 44L, 41, 82 | ORF45, 41, 82 | — |

| p54, 54 | — | — | — | — |

| p55, 98 | — | — | — | — |

| p56, 204 | p17, 43, 155 | 3R, 47, 121 | ORF31, 50, 154 | BB2226 in Bordetella bronchiseptica RB50 (41% identity, gi 33601210) |

| p31.1, 45, 153 | 17R, 46, 156 | ORF58, 44, 155 | ||

| p42.1, 45, 155 | 49L, 45, 154 | |||

| p55.1, 45, 154 | 57R, 44, 154 | |||

| p57, 100 | — | — | — | — |

| p58, 114 | p60, 46, 100 | 59R, 43, 100 | ORF59, 44, 103 | Mpe_A0538 in Methylibium petroleiphilum PM1 (48% identity, gi 124265731) |

—, no corresponding or similar ORF.

Mosaicism of the capsid assembly module of phiL7.

Terminase, the capsid portal protein, ClpP (the prohead protease), and the major capsid protein are collectively referred to as “capsid assembly proteins” in phages. We found that phiL7 p03 was similar to the large subunit of terminases from HK97 (NP_037698), HK022 (NP_037663), D3 (NP_061498), ST64B (NP_700375), and phiE125 (NP_536358), as well as to single proteins from X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages that do not have smaller subunits (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This suggests that the Xanthomonas phages may be capable of DNA packaging without the assistance of a small subunit. We found that p04 was similar (ca. 52% and 44% identity, respectively) to the HK97 family capsid portal proteins from Delftia acidovorans SPH-1 (YP_001562661) and Burkholderia pseudomallei 1710a (ZP_02109355), whereas p06 was similar (45% and 52% identity, respectively) to the major capsid proteins from HK97 (NP_037701) and D3 (NP_061502). ClpP (p05), which is essential for procapsid protein maturation in double-stranded DNA phages, is found in four families: U9 (T4-like Myoviridae), U35 (HK97-like Siphoviridae), S14 (ClpP protease), and S49 (E. coli peptidase IV) (30, 36). Interestingly, bioinformatic analysis classified phiL7 p05 into the S14 and not the U35 family, which contains the HK97-like proteins. These data suggest mosaicism in the phiL7 capsid assembly module, most likely resulting from horizontal gene transfer.

A gene encoding a tail fiber protein with domain duplications, thought to be important for host range determination in X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages, is absent from phiL7.

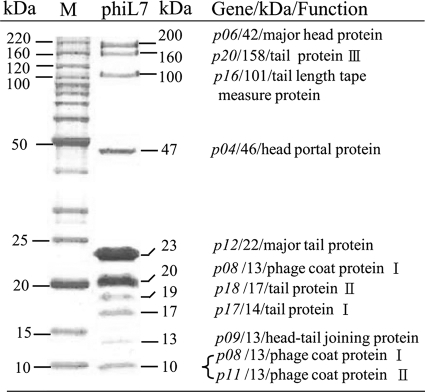

Using SDS-PAGE (10% [wt/vol] polyacrylamide) in conjunction with LC-MS/MS and N-terminal amino acid sequencing, we identified 10 phiL7 virion proteins: p04 (a capsid portal protein), p06 (a major capsid protein), p08 (phage coat protein I), p09 (capsid-tail joining protein), p11 (phage coat protein II), p12 (major tail protein), p16 (tail length tape-measure protein), p17 (tail protein I), p18 (tail protein II), and p20 (tail protein III) (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Among these proteins, eight had experimentally identified homologs in Xop411, whereas two (p09 and p18) were observed in phiL7 only, and homologs were merely predicted for X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages. We also observed oligomerization of two proteins. The major capsid protein (calculated to be 41 kDa) was observed at a position corresponding to 200 kDa in SDS-PAGE, suggesting oligomers consisting of five subunits. In addition, the phage coat protein, p08, with a calculated molecular mass of 13 kDa, was identified in 10-kDa and 20-kDa bands, indicating that this protein may be present in virions as a monomer or dimer.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE of phiL7 virion proteins. Proteins of purified phiL7 particles were separated in 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The protein bands were recovered, digested in the gel, and subjected to mass spectrometric analysis. On the right are the designations of the genes, their apparent molecular sizes, and their possible functions. Lane M contains DNA size markers.

We were unable to identify a homolog of the OP1 tail fiber protein (ORF25) thought to be involved in host range determination achieved by variation in the combinations of domain duplications at the N terminus (20). Further sequence comparisons of the corresponding proteins (p26) from Xop411 and Xp10 suggested that other components may serve together to determine host range (24). The absence of a homolog of ORF25 thus raises the question as to which phiL7 protein is responsible for host range determination. Furthermore, no domain duplication was found in any of the deduced or experimentally identified phiL7 virion proteins, suggesting that domain duplication may not be important for host range determination by phiL7. In phage lambda, the last C-terminal portion of the protein J (tail protein) has been shown to determine host specificity (2). Our computer analysis indicated that amino acids (aa) 1117 to 1229 of the phiL7 p20, annotated as tail protein III (Table 1), shared similarity with a functionally uncharacterized domain found in various bacteriophage host specificity proteins, including the one (between aa 845 and 925) present in lambda protein J (pfma09327: DUF1983). The similarity and identity shared between the domains in protein J and p20 were 41 and 16%, respectively. This finding suggest the possibility that p20 may be the tail protein involved in determination of host range. Whether p20 plays such a role will be tested in our laboratory by using p20 mutants we are currently constructing.

The phiL7 lysis cassette has four potential genes encoding holin, lysozyme, and two accessory proteins, Rz and Rz1.

For host lysis, double-stranded DNA phages commonly utilize the phage-encoded proteins holin and lysozyme and the accessory proteins Rz and Rz1 (41). Whereas holins and lysozymes have been studied extensively, roles for Rz and Rz1 have been determined only recently (3, 41). Bioinformatic searches among almost all phages of gram-negative hosts have identified Rz and Rz1 equivalents, with varied gene arrangements. For example, Rz1 may be embedded in, overlap with, or be separated from Rz. Rz has an N-terminal transmembrane domain that can locate to the inner membrane, and Rz1 is an outer membrane lipoprotein; these two proteins can thus form a complex that spans the periplasm, as required for the final step of host lysis. In some phages, one protein may play two roles (e.g., spanin of phage T1), or neither may be needed (e.g., in PaP3, Pf-WMP4, and P27) (41).

We found that phiL7 p28 was of the same size as and was 77% identical to the experimentally identified Xop411 lysozyme (25). P27 was predicted to be a holin, small in size (8 kDa) and similar to class III holins in having one transmembrane domain (aa 24 to 46) and a predicted periplasmic C terminus; the gene was located beside the lysozyme gene (37). In addition, p29 of phiL7 has an N-terminal transmembrane domain (aa 7 to 29) and a secretory signal, whereas p29.1 has a possible cleavage site for the lipoprotein signal peptidase, between aa 26 and 27 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Based on structural features, we predicted that p29 and p29.1 of phiL7 would encode Rz and Rz1, respectively, which are similar to the Rz and Rz1 equivalents of the Xanthomonas phages (Xp10, OP1, and Xp15) (41). The phiL7 Rz and Rz1 are 49% and 55% identical to the predicted Rz and Rz1 of Xp10, respectively. Finally, Xop411 may also possess overlapping Rz and Rz1 genes (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

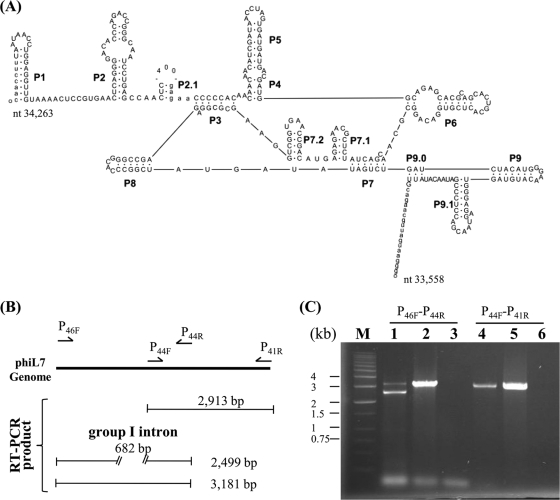

HNH endonuclease gene p45 is carried in an intron inserted into the DNA polymerase gene, and both spliced and nonspliced transcripts can be detected.

We predicted that phiL7 contains five HNH endonucleases. Sequence analysis showed that p07 had complete HNH and AP2 domains, indicating that it is a group I HNH endonuclease, whereas p49 and p56 each had only an HNH domain, indicating that these are group III enzymes. Similar to Xop411 p60, p58 is a group IV protein, because it had no AP2 domain and its intact HNH domain had two cysteine dyads (CX2C) flanking the conserved Asp/His residues, suggesting the requirement of zinc ion for function, as well as two boxes (DX2NL and CH) on the C-terminal side of the HNH domain (24). The fifth HNH endonuclease, p45, was unusual in that it had an HNH domain located at the C terminus, in contrast to typical HNH domains, which are located at the N terminus. In addition, the sequence was only 46% identical to that of ORF13 of phage Pf-WMP3 but showed no significant homology to any HNH endonucleases in the database. Moreover, the gene encoding p45 was contained within an intron of the DNA polymerase I gene (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

We found that phiL7 p46 encoded a polypeptide with an intact 3′→5′ exonuclease domain and the N terminus of a polymerase A domain, whereas p44 encoded the C terminus of the polymerase A domain of phage DNA polymerases. The region between p46 and p44 (682 bp; nt 33575 to 34256, including the p46 stop codon TAA) was a self-splicing group I intron (subgroup IA2; http://www.rna.whu.edu.cn/gissd/gIRfam.html), which contained p45 (Fig. 4A) (57). Removal of the predicted intron between p46 and p44 would give rise to a fusion protein with a molecular mass of 92.5 kDa, similar in size and amino acid sequence to DNA polymerase I from X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages Xp10, OP1, and Xop411 (24); phiKMV (NP_877458); and 1710b (YP_333053) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). To determine whether the intron was removed to produce a mature transcript, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed with primer pair P46F/P44R (Fig. 4B) and two amplicons were obtained—of 3,181 and 2,499 bp, respectively (Fig. 4B and C). The larger amplicon had the same length and sequence as the genomic region, indicating that it represents nonprocessed RNA, whereas the smaller amplicon contained the same sequence without the 682-bp intron, thus representing mature RNA (Fig. 4B). During the splicing assay of the group I intron inserted in the DNA polymerase gene of T7-like phages, nonprocessed RNA was not observed and it was speculated that the intron RNA may be highly structured (5). Thus, the phiL7 intron may be less structured or our experimental conditions may have favored PCR amplification.

FIG. 4.

Group I intron (subgroup IA2) in the predicted phiL7 DNA polymerase I gene and assay for the splicing. (A) Secondary structure of the intron. Exon and intron sequences are in lowercase and uppercase letters, respectively, and boundaries indicate the splicing sites. The vertical arrow indicates the 400-bp loop, which contains the first 375 bp of the HNH endonuclease gene p45 plus 25 bp from the upstream region. (B) Diagrammatic representation depicting the RT-PCR fragments that would be obtained using different primer pairs. Using primers P46F and P44R, products of 3,181 and 2,499 bp, representing nonprocessed and processed RNA, respectively, would be obtained. As a control, using primers P44F and P41R for amplification of the cDNA region encompassing p44 to p41, which had identical sequence to the genomic DNA, would yield a single product of 2,913 bp. (C) Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR fragments obtained from the splicing assays. PCRs were performed as described in Materials and Methods, and the PCR products were subjected to agarose gel (0.7%) electrophoresis. The primers used are labeled above the lanes. Lane M contains DNA size markers. The templates used were cDNA (lanes 1 and 4), phiL7 genome DNA (lanes 2 and 5), and RNA isolated from phiL7-infected X. campestris pv. campestris strain 17 (lanes 3 and 6). The 2,499- and 3,181-bp fragments in lane 1 represent processed and nonprocessed products, respectively. The 3,181-bp fragment can be seen in lane 2, while the 2,913-bp fragment is visualized in lanes 4 and 5.

Although a wide range of phages have been found to contain group I introns inserted into genes involved in DNA metabolism (4, 47), this is the first intron discovered in Xanthomonas phages.

phiL7 may have a protein functionally similar to the Xp10 p7 that controls the shift from host to viral RNAP.

Some double-stranded phages such as lambda utilize the host RNAP, modified by phage-encoded factors, for transcription (13, 45). In contrast, T7-like phages utilize phage-encoded RNAPs (7, 49). The siphophage Xp10 relies on both host and a viral RNAP (a single-subunit RNAP similar to the T7-type enzymes), and the shift from host to phage RNAP is controlled by protein p7 (73 aa, encoded by gene p45), which binds to and inhibits host RNAP and also acts as an antiterminator, allowing RNAP to pass through the intrinsic terminator for expression of late genes (38). Sequence analysis showed that phiL7 p35 was 29 to 31% identical to T7-like RNAPs (NP_041960, NP_523301, and NP_052071) and 46% identical to the RNAPs from X. oryzae pv. oryzae phages. However, we did not observe any phiL7 proteins that shared significant homology with Xp10 p7.

To test whether inhibition of host RNAP occurs upon infection with phiL7, we measured the RNAP activity in the phiL7-infected and uninfected Xc17 cells. Since a high degree of identity is shared between the RNAP of Xop411 and that of the Xp10, which had previously been demonstrated to exert inhibition to the host RNAP activity (26), crude extracts prepared from Xop411-infected and uninfected cells (X. oryzae pv. oryzae strain 21) were used as controls. The results indicated that 62 and 68% of the RNAP activities in X. campestris pv. campestris strain 17 were inhibited by the phiL7 infection when phage and host DNA, respectively, were used as the templates in the assays; stronger inhibition was observed in X. oryzae pv. oryzae strain 21 infected with Xop411, which caused ca. 85% inhibition in both templates (Table 3). These observations suggest that phiL7 may have a protein functionally similar to the Xp10 p7 that controls the shift from host to viral RNAP during transcription, although bioinformatic analysis did not reveal a homologue in the phiL7 genome. Such a protein is being identified in our laboratory by biochemical and genetic approaches, and the results will be published elsewhere.

TABLE 3.

Amounts of labeled [α-32P]UMP incorporated in the RNAP assaya

| Template | Amt (cpm) of [α-32P]UMP incorporated in X. campestris pv. campestris strain 17 |

% Inhibition | Amt (cpm) of [α-32P]UMP incorporated in X. oryzae pv. oryzae strain 21 |

% Inhibition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected | Infected with Xc17 | Uninfected | Infected with Xop411 | |||

| Phage DNA | 20,475 | 7,856 | 62 | 52,304 | 7,317 | 86 |

| Host DNA | 14,828 | 4,751 | 68 | 42,402 | 6,795 | 84 |

Crude extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Enzyme activity is expressed as cpm obtained from scintillation counting. Data are averages from two independent experiments.

T7 RNAP consists of a large C-terminal domain containing the principal polymerization activity and a small N-terminal domain involved in promoter recognition, DNA melting, and binding to the 5′ end of elongating RNA products to prevent abortive transcription (6, 39). In addition, three major loops have been identified: a loop that recognizes AT-rich sequences, required for normal polymerization and promoter binding; an intercalating hairpin loop required for separating the T7 promoter and maintaining the upstream transcription bubble; and a specificity loop involved in stabilizing the T7 promoter (6, 8). All important amino acid residues in the large C terminus of T7 RNAP were well conserved in phiL7 RNAP (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material): Asp507 and Asp741 in phiL7 RNAP, corresponding to Asp537 and Asp812, respectively, in the active site of T7 RNAP; Lys577 and Tyr585 in phiL7 RNAP, corresponding to the catalytic residues Lys631 and Tyr811, respectively, in proximity to the active site of T7 RNAP; and His714 in phiL7 RNAP, corresponding to His784 of T7 RNAP, for holding short transcripts (34, 53). However, the amino acid residues at the corresponding sites of major loops varied greatly in sequence and length (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). These differences suggest that phiL7 RNAP may recognize different sequences as promoters.

Seven possible promoter and four terminator sequences were identified.

A bioinformatic search, by following an existing reference for finding T7-like promoters (11), failed to identify a T7 RNAP promoter-like sequence in the phiL7 genome, although phiL7 has a T7-like RNAP. This result is consistent with the previous report, showing that a group of T7-like phages (e.g., phiKMV, Xp10, and PaP3) encoded a T7-like RNAP but contained no T7 RNAP promoter-like sequence (9). Based on known Xp10 promoter sequences and −35 to −10 consensus sequences for E. coli σ70, seven phiL7 promoters were predicted, in the 5′-flanking regions of p07, p20, p24, p35, p38, p49, and p57 (Fig. 2 and see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Interestingly, the predicted promoter of p35 (RNAP gene) has four −35 to −10 sequences in tandem. Using the same algorithm as that employed to analyze Xp10 terminators (38), we identified four possible terminators in phiL7, located at the 3′-flanking regions of p15, p18, and p54 and between p29.1 and p30 (Fig. 2 and see Table S3 in the supplemental material).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the RNA Research Group (College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University, People's Republic of China) for drawing the group I intron structure and Pei-Lan Lin for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants NSC 93-2311-B-166-001, 94-2311-B-166-001, 95-2311-B-005-005-MY3, and 96-2317-B-005-009 from the National Science Council of the Republic of China.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 October 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkane, E., F. Orlik, J. F. Stegmeier, A. Charbit, M. Winterhalter, and R. Benz. 2006. Interaction of bacteriophage lambda with its cell surface receptor: an in vitro study of binding of the viral tail protein gpJ to LamB (maltoporin). Biochemistry 45:2708-2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry, J., E. J. Summer, D. K. Struck, and R. Young. 2008. The final step in the phage infection cycle: the Rz and Rz1 lysis proteins link the inner and outer membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 70:341-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonocora, R. P., and D. A. Shub. 2009. A likely pathway for formation of mobile group I introns. Curr. Biol. 19:223-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonocora, R. P., and D. A. Shub. 2004. A self-splicing group I intron in DNA polymerase genes of T7-like bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 186:8153-8155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheetham, G. M., D. Jeruzalmi, and T. A. Steitz. 1999. Structural basis for initiation of transcription from an RNA polymerase-promoter complex. Nature 399:80-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheetham, G. M., D. Jeruzalmi, and T. A. Steitz. 1998. Transcription regulation, initiation, and “DNA scrunching” by T7 RNA polymerase. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant Biol. 63:263-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheetham, G. M., and T. A. Steitz. 1999. Structure of a transcribing T7 RNA polymerase initiation complex. Science 286:2305-2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, Z., and T. D. Schneider. 2005. Information theory based T7-like promoter models: classification of bacteriophages and differential evolution of promoters and their polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:6172-6187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng, C. Y., Y. J. Yu, and M. T. Yang. Coexpression of omega subunit in E. coli is required for the maintenance of enzymatic activity of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris RNA polymerase. Protein Expr. Purif., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Chopin, A., H. Deveau, S. D. Ehrlich, S. Moineau, and M. C. Chopin. 2007. KSY1, a lactococcal phage with a T7-like transcription. Virology 365:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flaherty, J. E., B. K. Harbaugh, J. B. Jones, G. C. Somodi, and L. E. Jackson. 2001. H-mutant bacteriophages as a potential biocontrol of bacterial blight of geranium. Hortscience 36:98-100. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman, D. I., and D. L. Court. 1995. Transcription antitermination: the lambda paradigm updated. Mol. Microbiol. 18:191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu, J.-F., and Y.-H. Tseng. 1990. Construction of lactose-utilizing Xanthomonas campestris and production of xanthan gum from whey. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:919-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill, J. J., and S. T. Abedon. November 2003. Bacteriophage ecology and plants. APSnet Feature. http://www.apsnet.org/online/feature/phages/.

- 16.Gill, J. J., A. M. Svircev, R. Smith, and A. J. Castle. 2003. Bacteriophages of Erwinia amylovora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2133-2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayward, A. C. 1993. The host of Xanthomonas, p. 51-54. In J. G. Swings and E. L. Civerolo (ed.), Xanthomonas. Chapman & Hall, London, United Kingdom.

- 18.Hung, C. H., H. C. Wu, and Y. H. Tseng. 2002. Mutation in the Xanthomonas campestris xanA gene required for synthesis of xanthan and lipopolysaccharide drastically reduces the efficiency of bacteriophage phiL7 adsorption. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 291:338-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung, C. H., C. F. Yang, C. Y. Yang, and Y. H. Tseng. 2003. Involvement of tonB-exbBD1D2 operon in infection of Xanthomonas campestris phage phiL7. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 302:878-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue, Y., T. Matsuura, and T. Ohara. 2006. Bacteriophage OP1, lytic for Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, changes its host range by duplication and deletion of the small domain in the deduced tail fiber gene. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 72:111-118. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue, Y., T. Matsuura, and T. Ohara. 2006. Sequence analysis of the genome of OP2, a lytic bacteriophage of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 72:104-110. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones, J. B., L. E. Jackson, B. Balogh, A. Obradovic, F. B. Iriarte, and M. T. Momol. 2007. Bacteriophages for plant disease control. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 45:245-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo, T. T., T. C. Huang, and T. Y. Chow. 1969. A filamentous bacteriophage from Xanthomonas oryzae. Virology 39:548-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, C. N., R. M. Hu, T. Y. Chow, J. W. Lin, H. Y. Chen, Y. H. Tseng, and S. F. Weng. 2007. Comparison of genomes of three Xanthomonas oryzae bacteriophages. BMC Genomics 8:442-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, C. N., J. W. Lin, T. Y. Chow, Y. H. Tseng, and S. F. Weng. 2006. A novel lysozyme from Xanthomonas oryzae phage phiXo411 active against Xanthomonas and Stenotrophomonas. Protein Expr. Purif. 50:229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao, Y. D., and T. T. Kuo. 1986. Loss of sigma-factor of RNA polymerase of Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzae during phage Xp10 infection. J. Biol. Chem. 261:13714-13719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liew, K. W., and A. M. Alvarez. 1981. Biological and morphological characterization of Xanthomonas campestris bacteriophages. Phytopathology 71:269-273. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin, N. T., R. Y. Chang, S. J. Lee, and Y. H. Tseng. 2001. Plasmids carrying cloned fragments of RF DNA from the filamentous phage phiLf can be integrated into the host chromosome via site-specific integration and homologous recombination. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:425-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin, N. T., B. Y. You, C. Y. Huang, C. W. Kuo, F. S. Wen, J. S. Yang, and Y. H. Tseng. 1994. Characterization of two novel filamentous phages of Xanthomonas. J. Gen. Virol. 75:2543-2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, J., and A. Mushegian. 2004. Displacements of prohead protease genes in the late operons of double-stranded-DNA bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 186:4369-4375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marco, G. M., and R. E. Stall. 1983. Control of bacterial spot of pepper initiated by strains of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria that differ in sensitivity to copper. Plant Dis. 67:779-781. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuzaki, S., M. Rashel, J. Uchiyama, S. Sakurai, T. Ujihara, M. Kuroda, M. Ikeuchi, T. Tani, M. Fujieda, H. Wakiguchi, and S. Imai. 2005. Bacteriophage therapy: a revitalized therapy against bacterial infectious diseases. J. Infect. Chemother. 11:211-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore, D. D., K. J. Denniston, and F. R. Blattner. 1981. Sequence organization of the origins of DNA replication in lambdoid coliphages. Gene 14:91-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osumi-Davis, P. A., M. C. de Aguilera, R. W. Woody, and A. Y. Woody. 1992. Asp537, Asp812 are essential and Lys631, His811 are catalytically significant in bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase activity. J. Mol. Biol. 226:37-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parkinson, N., V. Aritua, J. Heeney, C. Cowie, J. Bew, and D. Stead. 2007. Phylogenetic analysis of Xanthomonas species by comparison of partial gyrase B gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:2881-2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rawlings, N. D., E. O'Brien, and A. J. Barrett. 2002. MEROPS: the protease database. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:343-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savva, C. G., J. S. Dewey, J. Deaton, R. L. White, D. K. Struck, A. Holzenburg, and R. Young. 2008. The holin of bacteriophage lambda forms rings with large diameter. Mol. Microbiol. 69:784-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Semenova, E., M. Djordjevic, B. Shraiman, and K. Severinov. 2005. The tale of two RNA polymerases: transcription profiling and gene expression strategy of bacteriophage Xp10. Mol. Microbiol. 55:764-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sousa, R., Y. J. Chung, J. P. Rose, and B. C. Wang. 1993. Crystal structure of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase at 3.3 Å resolution. Nature 364:593-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su, M. J., M. C. Lai, S. F. Weng, and Y. H. Tseng. 1990. Characterization of phage φL7 and transfection of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris by the phage DNA. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 31:197-203. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Summer, E. J., J. Berry, T. A. Tran, L. Niu, D. K. Struck, and R. Young. 2007. Rz/Rz1 lysis gene equivalents in phages of gram-negative hosts. J. Mol. Biol. 373:1098-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutherland, L. W. 1990. Biotechnology of microbial exopolysaccharides, p. 79. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY.

- 43.Sutton, M. D., H. Katznelson, and C. Quadling. 1958. A bacteriophage that attacks numerous phytopathogenic Xanthomonas species. Can. J. Microbiol. 4:493-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutton, M. D., and C. Quadling. 1963. Lysogeny in a strain of Xanthomonas campestris. Can. J. Microbiol. 9:821-828. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeda, Y., Y. Oyama, K. Nakajima, and T. Yura. 1969. Role of host RNA polymerase for lambda phage development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 36:533-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thayer, P. L., and R. E. Stall. 1961. A survey of Xanthomonas vesicatoria resistance to streptomycin. Proc. Fla. Hortic. Soc. 75:163-165. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tourasse, N. J., and A. B. Kolsto. 2008. Survey of group I and group II introns in 29 sequenced genomes of the Bacillus cereus group: insights into their spread and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:4529-4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsurimoto, T., H. Kouhara, and K. Matsubara. 1985. Origin and initiation sites of lambda dv DNA replication in vitro. Basic Life Sci. 30:151-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tunitskaya, V. L., and S. N. Kochetkov. 2002. Structural-functional analysis of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Biochemistry (Moscow) 67:1124-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, H. J., C. M. Cheng, C. N. Wang, and T. T. Kuo. 1999. Transcription of the genome of the filamentous bacteriophage cf from both plus and minus DNA strands. Virology 256:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watanabe, M., K. W. Naito, K. W. Kaneko, H. Nabasama, and D. Hosokawa. 1980. Some properties of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris phage. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 46:517-525. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss, B. D., M. A. Capage, M. Kessel, and S. A. Benson. 1994. Isolation and characterization of a generalized transducing phage for Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. J. Bacteriol. 176:3354-3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woody, A. Y., S. S. Eaton, P. A. Osumi-Davis, and R. W. Woody. 1996. Asp537 and Asp812 in bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase as metal ion-binding sites studied by EPR, flow-dialysis, and transcription. Biochemistry 35:144-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang, B. Y., H. F. Tsai, and Y. H. Tseng. 1988. Broad host range cosmid pLAFR1 and non-mucoid mutant XCP20 provide a suitable vector-host system for cloning genes in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Zhonghua Minguo Weishengwu Ji Mianyixue Zazhi 21:40-49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang, T. C., G. H. Wu, and Y. H. Tseng. 2002. Isolation of a Xanthomonas campestris strain with elevated beta-galactosidase activity for direct use of lactose in xanthan gum production. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 35:375-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yuzenkova, J., S. Nechaev, J. Berlin, D. Rogulja, K. Kuznedelov, R. Inman, A. Mushegian, and K. Severinov. 2003. Genome of Xanthomonas oryzae bacteriophage Xp10: an odd T-odd phage. J. Mol. Biol. 330:735-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou, Y., C. Lu, Q. J. Wu, Y. Wang, Z. T. Sun, J. C. Deng, and Y. Zhang. 2008. GISSD: group I intron sequence and structure database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:D31-D37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.