Abstract

Vibrio tubiashii, a causative agent of severe shellfish larval disease, produces multiple extracellular proteins, including a metalloprotease (VtpA), as potential virulence factors. We previously reported that VtpA is toxic for Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) larvae. In this study, we show that extracellular protease production by V. tubiashii was much reduced by elevated salt concentrations, as well as by elevated temperatures. In addition, V. tubiashii produced dramatically less protease in minimal salts medium supplemented with glucose or sucrose as the sole carbon source than with succinate. We identified a protein that belongs to the TetR family of transcriptional regulators, VtpR, which showed high homology with V. cholerae HapR. We conclude that VtpR activates VtpA production based on the following: (i) a VtpR-deficient V. tubiashii mutant did not produce extracellular proteases, (ii) the mutant showed reduced expression of a vtpA-lacZ fusion, and (iii) VtpR activated vtpA-lacZ in a V. cholerae heterologous background. Moreover, we show that VtpR activated the expression of an additional metalloprotease gene (vtpB). The deduced VtpB sequence showed high homology with a metalloprotease, VhpA, from V. harveyi. Furthermore, the vtpR mutant strain produced reduced levels of extracellular hemolysin, which is attributed to the lower expression of the V. tubiashii hemolysin genes (vthAB). The VtpR-deficient mutant also had negative effects on bacterial motility and did not demonstrate toxicity to oyster larvae. Together, these findings establish that the V. tubiashii VtpR protein functions as a global regulator controlling an array of potential virulence factors.

Vibriosis is one of the most destructive larval diseases for bivalve mollusks and frequently occurs in shellfish rearing facilities. The disease is thought to be a major cause of mortalities of various shellfish larvae (9, 15, 47). Recent outbreaks of this bacterial disease have become a major threat for shellfish hatcheries in the northwest region of the United States, which has led to serious economical losses in recent years (9). It is therefore of prime importance to understand the disease mechanism and eventually prevent the significant drop in the production of shellfish larvae due to vibriosis.

The genus Vibrio consists of more than 30 known species, causing a variety of both human and aquatic animal diseases. One of the shellfish pathogenic Vibrio species, Vibrio tubiashii, is a recently reemerging pathogen of several species of bivalve larvae including oysters, clams, and geoducks (9, 10). Disease caused by V. tubiashii is characterized by a reduction in larval motility, detached vela, and necrotic soft tissue, accompanied by high mortality rates (42).

Although only limited information is available about many aspects of V. tubiashii, including virulence factors produced, previous studies demonstrated that V. tubiashii strains, including RE22 and RE98, showed the highest degree of disease severity (10), with the production of high levels of extracellular metalloprotease (VtpA) and hemolysin (VthA) (7, 19, 25). We showed in a previous study that the purified VtpA protein caused significantly high toxicity to oyster larvae, strongly suggesting that the VtpA is a structural toxin to the host (18). Moreover, mutant studies clarified that the VtpA and VthA proteins are responsible for a majority of the proteolytic and hemolytic activities, respectively, of the V. tubiashii culture supernatants (17, 19). In addition, we recently observed that the purified VtpA directly inactivates VthA hemolysin (17). Although virulence of V. tubiashii is likely multifactorial, the metalloprotease VtpA appears to be the main secreted toxin in V. tubiashii supernatants (18, 19).

Typically, this type of metalloprotease is tightly regulated by a TetR family of DNA-binding transcriptional regulatory proteins in a variety of Vibrio species (5, 22, 23, 35, 39). For example, in V. vulnificus a deletion of the TetR family regulator, SmcR, results in severely reduced production of the VvpE metalloprotease (22). HapR, another homolog from V. cholerae, positively controls production of a metalloprotease (HapA) similar to VtpA (23). In addition, it is reported that this type of transcriptional regulator is involved in the regulation of multiple virulence factors, including biofilm, exopolysaccharides, motility, and type III effectors (32), suggesting that the regulatory proteins act as global regulators in various Vibrio species.

In the present study, regulation of the production of virulence factors in V. tubiashii is investigated. Our studies included not only the effects of environmental factors on extracellular protease production in V. tubiashii but also characterization and analyses of the roles of a DNA-binding transcriptional regulator, VtpR. In addition, we investigated the direct interactions between the VtpR protein and potential target genes, including the vtpA metalloprotease in V. tubiashii.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. All bacterial strains are kept at −80°C in 20% glycerol stocks. V. tubiashii and V. cholerae strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with a final concentration of 1% sodium chloride unless specified otherwise. Escherichia coli strains were grown in LB medium. V. tubiashii was also grown in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 1% sodium chloride and 0.5% (vol/vol) appropriate carbon sources. Although E. coli and V. cholerae strains were grown at 37°C, V. tubiashii was grown at 30°C unless specified otherwise. When required, antibiotics were supplemented as follows: ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 5 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| V. tubiashii | ||

| RE22 | Wild type | 10 |

| vtpA::cmR | vtpA::Cmr strain of RE22 | 17 |

| vtpR::cmR | vtpR::Cmr strain of RE22 | This study |

| V. cholerae | ||

| 3083 | Wild type | 23 |

| O395N1ΔZ | lacZ and ctxA derivative of wild-type strain O395 | Lab collection |

| E. coli | ||

| Top10 | Cloning host | Invitrogen |

| BW25113 | Conjugation donor | 6 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | Apr; cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pBAD-TOPO | Apr; expression vector | Invitrogen |

| pBAD-vtpR | Apr; vtpRRE22 gene in pBAD-TOPO | This study |

| pBAD-hapR | Apr; hapR3083 gene in pBAD-TOPO | This study |

| pLAFR5 | Tcr; cosmid cloning vector | 24 |

| pLAFR5-vtpR | Tcr; vtpR gene of RE22 in pLAFR5 | This study |

| pLAFR5-vtpR::cmR | Tcr Cmr; vtpR derivative of pLAFR5-vtpR | This study |

| pMP220 | Tcr; promoter-probe vector | 43 |

| pvthAB-lacZ | Tcr; vtpAB-lacZ in pMP220 | 17 |

| pvtpA-lacZ | Tcr; vtpA-lacZ in pMP220 | This study |

| pvtpB-lacZ | Tcr; vtpB-lacZ in pMP220 | This study |

| pvtpR-lacZ | Tcr; vtpR-lacZ in pMP220 | This study |

| pKD3 | Cmr; template for PCR amplification for red recombinase-mediated recombination | 6 |

| pKD46 | Apr; plasmid encoding red recombinase | 6 |

| pRK2013 | Mob+ Tra+ Kmr | 11 |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance.

V. tubiashii genes.

All PCR and cloning reactions were conducted by using standard procedures (1). Sequences for the vtpR (accession no. GQ121130) and vtpB (accession no. GQ121132) open reading frames (ORFs) were obtained by PCR using genomic DNA of the V. tubiashii strain RE22 with primer pairs based on homologous genes from various Vibrio species. Several primer pairs per gene were designed, and PCRs of all combinations were performed under low-stringency conditions to find a pair that successfully amplified a segment of the V. tubiashii genome. These PCR products were then cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by using a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The resulting clones were sequenced at the Oregon State University Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing core lab facility using M13 forward and reverse primers. Sequences were verified by BLAST searches. To obtain the entire ORF for these genes, inverse PCR was performed as previously described (37) with primers designed from the V. tubiashii sequences. Products obtained from inverse PCR were TA cloned into pCR 2.1-TOPO and sequenced using the M13 primers. The Oregon State University Center for Genomic Research and Biocomputing website was used for bioinformatic tools (http://bioinfo.cgrb.oregonstate.edu/).

V. tubiashii chromosomal DNA from strain RE22 and the vtpR::cmR strain was prepared by using a Qiagen DNEasy Blood and Tissue kit protocol for the preparation of gram-negative bacteria. Plasmids were purified according to the Qiagen spin miniprep kit protocol.

Construction of a V. tubiashii VtpR-deficient mutant.

A plasmid containing the vtpR gene was obtained from the V. tubiashii strain RE22 library by screening pools of colonies by standard PCR using the vtpR-specific primers. The vtpR-containing plasmid, pLAFR5-vtpR, was then mutagenized by deleting the entire ORF of vtpR via the lambda red recombinase system (6), using hybrid lambda red-vtpR primers and pKD3 (6) as the template. Competent cells of E. coli BW25113 carrying pKD46 (6) and pLAFR5-vtpR were electroporated with a linear PCR product containing the chloramphenicol resistance cassette flanked by the target gene sequences with the same orientation. The resulting chloramphenicol and tetracycline resistance clones were confirmed for the correct insertion by PCR, creating pLAFR5-vtpR::cmR. E. coli strain Top10 cells carrying the mutagenized plasmid were then conjugated into V. tubiashii RE22 by triparental matings with the helper E. coli strain HB101 carrying pRK2013. V. tubiashii carrying pLAFR5-vtpR::cmR was grown in LB 1% NaCl medium without the vector marker (tetracycline) and subcultured overnight twice, selected for the marker (chloramphenicol) inserted into the target gene, and then tested for the loss of the vector marker (tetracycline). The allelic exchange after double homologous recombination was confirmed by PCR. For complementation experiments, pLAFR5-vtpR was introduced into the vtpR-deficient mutant by triparental matings.

Construction of E. coli and V. tubiashii carrying lacZ fusion plasmids and β-galactosidase assay.

For analyzing effects of VtpR (or the homolog) on expression of the potential target genes in E. coli and V. cholerae hapR mutant backgrounds, plasmids carrying the vtpR or hapR genes from the V. tubiashii strain RE22 and V. cholerae strain 3083, respectively, were constructed. Forward and reverse primers were designed based on the published gene sequences (accession nos. GQ121130 from V. tubiashii and AF000716 from V. cholerae). The amplified DNA fragments were cloned into pBAD-TOPO and introduced into chemically competent E. coli Top10 (Invitrogen) and V. cholerae O395N1ΔZ cells. Plasmids carrying the inserts in the desired orientation (i.e., placing the gene under the control of the arabinose-inducible promoter) were identified and confirmed by sequencing. To construct the lacZ fusion plasmid, PCR-amplified DNA fragments containing ∼600 bp upstream from the putative translational start site of each gene were cloned into BglII-XbaI sites of pMP220 (43) to make plasmids pvtpA-lacZ pvtpB-lacZ, pvthAB-lacZ, and pvtpR-lacZ, which were then electroporated into E. coli strain Top10 or V. cholerae O395N1ΔZ carrying pBAD-TOPO, pBAD-vtpR, or pBAD-hapR. The presence of the pBAD expression and the appropriate lacZ fusion plasmids was confirmed by antibiotic resistance, blue/white screening, and PCR.

V. cholerae or E. coli strains were grown at 30°C in LB medium supplemented with 1% NaCl and 100 μg of ampicillin ml−1 in the absence or presence of 0.02% (for V. cholerae) or 0.2% (for E. coli) l-arabinose. Samples were harvested at the stationary phase of bacterial growth (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of ∼3.0) and analyzed for β-galactosidase activities. To compare expression of the LacZ fusions mentioned above between V. tubiashii strains the RE22 and vtpR-deficient mutant, lacZ plasmids were introduced into these V. tubiashii strains by triparental mating. The β-galactosidase assays were performed according to the method of Miller (31).

Larva toxicity assay.

Toxicity assays were performed as described previously (18). V. tubiashii strains were cultured until stationary phase (∼24 h in LB medium supplemented with 1% NaCl) and centrifuged, and the supernatants were filter sterilized. Ten-day-old oyster larvae (Coast Seafoods Company) in sterile seawater were used for the assay. The health of the larvae was confirmed by evaluating the larva samples treated with or without the medium control. Toxicity to larvae was determined by visualization on an inverted microscope. We considered oyster larvae dead when the larvae stopped moving, the velum was grossly damaged, and the larvae appeared to be darkened, similar to traits described by Garland et al. (13).

Enzyme assays.

Bacterial culture supernatants were assayed for proteolytic and hemolytic activities as previously described by Hasegawa et al. (19) using 1% azocasein and 3.5% sheep blood (Colorado Serum Co.), respectively, with the exception that the absorbance of hemolytic activities were measured at 440 nm. The proteolytic activity was also assessed by using zymogram gel electrophoresis as described by Hasegawa et al. (19).

Swimming motility tests.

Bacterial cells were inoculated onto LB soft agar (0.4%) supplemented with 3% NaCl and point inoculated at 30°C by needle stabbing the bacterial cells into soft-agar plates. Motility of the bacteria was visually examined.

RESULTS

Effects of environmental factors on production of extracellular protease in V. tubiashii.

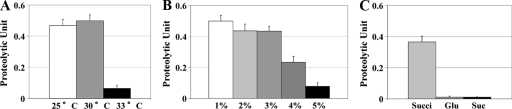

In preliminary experiments, we observed that V. tubiashii strain RE22 failed to grow well at temperatures higher than 34°C but showed only slightly reduced growth at 33°C, which was still comparable to that at 25 or 30°C. To test whether there is any effect of temperature on production of extracellular protease, V. tubiashii strain RE22 was grown at these temperatures to a similar cell density at the stationary phase (an OD600 of ∼3.2). Figure 1A shows that culture supernatants of V. tubiashii grown at 33°C contained significantly lower levels of proteolytic activities than those at 25 or 30°C, whereas there was not any significant difference in protease production between 25 and 30°C. These results indicated that elevated temperatures (no less than 33°C) resulted in reduced production of extracellular protease by V. tubiashii.

FIG. 1.

Effects of temperatures (A), NaCl concentrations (B), and carbon sources (C) on extracellular proteolytic activities. To examine the effects of temperatures and NaCl concentrations, V. tubiashii cultures were grown at 30°C in LB medium supplemented with 1% NaCl unless specified otherwise. For effects of carbon sources, bacterial cultures were grown in M9 supplemented with 1% NaCl at 30°C. Succi, succinate; Glu, glucose; Suc, sucrose. Samples were harvested at the stationary phase of the bacterial growth and analyzed for proteolytic activities. The error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3).

Although V. tubiashii strain RE22 showed healthy growth in a salt concentration of 1 or 5% in the medium, the strain grew even better with 2 to 4% NaCl concentrations. However, the strain showed relatively poor growth at salt concentrations higher than 6% (data not shown). To examine whether salinity affects the production of extracellular protease, we grew V. tubiashii strain RE22 in a variety of NaCl concentrations and assayed for the proteolytic activities. As shown in Fig. 1B, V. tubiashii produced reduced amounts of extracellular protease in 4% salt compared to 1 to 3%. In addition, a salt concentration higher than 5% caused a more severe reduction in the protease production (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, there were no statistically significant differences in the proteolytic activities produced among 1 to 3% salt conditions (Fig. 1B). Adjusting salt concentrations in the protease assay did not significantly affect the enzymatic activities (data not shown). Together, these results suggested that excessive high-salt growth conditions lead to reduced amounts of extracellular protease production.

To investigate whether sugar contents show any effect on protease production in V. tubiashii, we grew V. tubiashii strain RE22 in defined minimal medium supplemented with succinate, glucose, or sucrose as the sole carbon source. We used minimal medium because the addition of glucose and sucrose in LB medium caused a severe reduction in bacterial growth (data not shown), with similar observations reported in V. cholerae (48). Figure 1C shows that culture supernatants of V. tubiashii contained barely detectable levels of protease in the minimal medium supplemented with glucose or sucrose compared to succinate, indicating that both glucose and sucrose cause severe reductions in protease production.

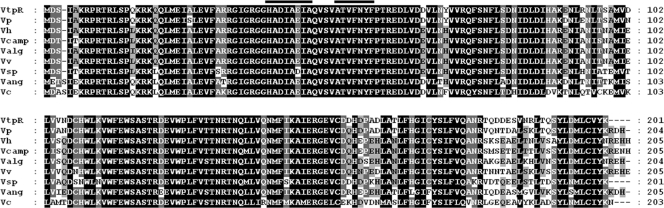

Sequence analyses of a TetR family transcriptional regulator, VtpR, in V. tubiashii.

It has been reported that metalloprotease production is controlled by the TetR family of transcriptional regulators in a variety of Vibrio species (5, 22, 23). The homolog from V. tubiashii strain RE22 was cloned by PCR, named vtpR. The full sequences of the upstream and downstream ORFs surrounding the vtpR gene were also obtained (data not shown) and showed significantly high homology with hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (hpt) and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (lpd) genes, respectively. In addition, a partial ORF encoding a hypothetical carbonic anhydrase was identified downstream of the hpt gene (data not shown). Similar genetic arrangements are found in the genomic regions flanking the vtpR homologs in most Vibrio species, including V. vulnificus, V. parahaemolyticus, and V. splendidus (data not shown).

The coding region of the vtpR gene is 606 bp, which is predicted to encode a 201-amino-acid residue protein. The deduced VtpR protein showed high homology to several TetR family transcriptional regulators from various Vibrio species, including OpaR (V. parahaemolyticus 92% identity), SmcR (V. vulnifucus 86%), LuxR (V. harveyi 84%), and HapR (V. cholerae 75%) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of VtpR with those from a variety of Vibrio species. Numbers on the right in the alignment refer to the positions of the amino acid residues. The black bar indicates the previously identified HTH motifs by De Silva et al. (8). Black-shaded areas indicate identical amino acids in all strains, and gray-shaded areas indicate identical or similar amino acids in five or more strains at any position. The following sequences were aligned by using CLUSTAL W: VtpR homolog of V. parahaemolyticus strain 16 (accession no. EED25255), V. harveyi strain HY01 (accession no. ZP_01988477), V. campbellii strain AND4 (accession no. ZP_02197335), V. alginolyticus strain 12G01 (accession no. ZP_01262548), V. vulnificus strain YJ016 (accession no. NP_935563), V. splendidus strain LGP32 (accession no. YP_002418121), Listonella anguillarum (accession no. AF457643), and V. cholerae strain 3083 (accession no. AF000716).

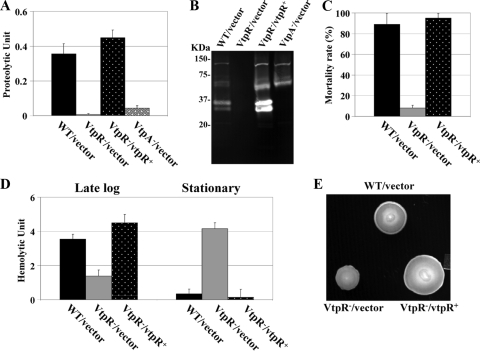

Mutation of VtpR results in altered production of extracellular products, reduced oyster larval toxicity, and reduced swimming motility in V. tubiashii.

To determine the effects of VtpR on extracellular protease production in V. tubiashii, we constructed a deletion mutant of the vtpR gene and assayed for proteolytic activities in culture supernatants. Figure 3A shows that culture supernatants of the vtpR::cmR strain contained virtually nondetectable levels of protease. Interestingly, the protease levels of the vtpR− mutant were even less than those of the metalloprotease vtpA::cmR mutant strain (Fig. 3A). The vtpR containing plasmid fully restored production of extracellular protease in the vtpR::cmR strain (Fig. 3A). Proteolytic activity was also assessed by using zymogram gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3B). Compared to the wild type, the vtpR mutant lacked the major proteolytic bands of the approximate sizes of 35 and 28 kDa (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the mutant showed virtually no detectable proteolytic band in the gel (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Analyses of various phenotypes of a VtpR-deficient mutant of V. tubiashii strain RE22. Extracellular protease production (A), protease zymogram profile (B), toxicity to oyster larvae (C), extracellular hemolysin production (D), and swarming motility (E) were compared. Bacteria were grown in LB medium supplemented with 1% NaCl at 30°C and harvested at the stationary phase (OD600 of ∼3.2). For the hemolysin assay, cells were also harvested at the late log phase (OD600 of ∼1.8). For the toxicity assay, filter-sterilized supernatants were added to a final concentration of 0.5%. The error bars indicate the standard deviations (n = 3). For motility assay, LB soft agar supplemented with 3% NaCl was used. WT, wild type.

To test whether culture supernatants of the VtpR-deficient mutant are toxic, we performed toxicity assays using oyster larvae. Culture supernatants of the vtpR::cmR strain caused only minimal toxicity to oyster larvae, whereas those of both the wild-type strain and the complemented mutant showed much higher larval toxicity (Fig. 3C).

To test whether hemolysin production is subject to the VtpR regulatory mechanism, we compared the hemolytic activities of culture supernatants between the wild-type and vtpR::cmR strains. As shown in Fig. 3D, at late log phase (OD600 = 1.8), the mutant produced much reduced amounts of hemolysin compared to the wild-type strain. Introduction of a vtpR-containing plasmid restored the hemolysin production at this growth phase (Fig. 3D). However, at stationary phase (OD600 = 3.2) the hemolytic activities in supernatants of the wild-type strain were diminished (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, supernatants of the vtpR mutant contained higher levels of hemolytic activities at the stationary phase (Fig. 3D). Introduction of the vtpR plasmid into the mutant reduced hemolytic activities at the stationary phase to levels comparable to the wild-type level (Fig. 3D).

Mutations in the TetR family of transcriptional regulators have been reported to affect bacterial motility, with a mutation in smcR in V. vulnificus resulting in reduced motility in soft-agar plates (20). To examine whether the bacterial motility is altered in the vtpR::cmR strain, we assayed the wild type and the mutant for motility in soft-agar medium. Compared to the wild-type strain, the vtpR mutant showed a greatly reduced swimming motility, which was restored by the vtpR-containing plasmid (Fig. 3E).

Identification and sequence analyses of a second extracellular metalloprotease, VtpB, in V. tubiashii.

Although the V. tubiashii VtpA is responsible for the majority of proteolytic activities in the culture supernatants, residual proteolytic activities are consistently found in culture supernatants of the vtpA mutant (Fig. 3A) (18, 19), which strongly suggested that there should be another protease that is regulated by VtpR. Mass spectrophotometry analyses of V. tubiashii supernatants indicated the presence of another metalloprotease, which is similar but distinct from VtpA (data not shown).

The entire ORF sequence of vtpB from V. tubiashii strain RE22 was obtained by PCR. The 2,340-bp metalloprotease gene is predicted to encode a 779-amino-acid protein. Based on the deduced amino acid sequence, the size of the protein was calculated to be ∼85 kDa. As found in VtpA, as well as in other metalloproteases (33), VtpB possesses a signal peptide, an N-terminal propeptide, a mature protease, and a C-terminal propeptide (34, 45). Alignment results (data not shown) revealed that VtpB shares high homology with several metalloproteases from other marine Vibrio species, including V. campbellii, V. harveyi, and V. splendidus (ca. 88 to 90% similarity). Comparative sequence analyses of VtpB with VtpA revealed that these distinct metalloproteases share only 61% similarity, although both metalloproteases share significantly high homology in the mature protease regions that contain the catalytically essential zinc-binding motifs (data not shown). Together, these results show that V. tubiashii encodes at least two secreted metalloproteases.

Effects of VtpR on expression of metalloprotease (vtpA and vtpB), hemolysin (vthAB), and vtpR genes in heterologous hosts.

The vtpR mutant studies suggested that V. tubiashii VtpR positively controls the production of extracellular proteolytic and hemolytic activities (Fig. 3). To examine whether VtpR directly regulates the vtpA, vtpB, or vthAB genes, we created strains that carry a vtpR plasmid, as well as a plasmid where the lacZ gene was fused to either of these genes. We used E. coli strain Top10 as well as a hapR mutant strain of V. cholerae (O395N1ΔZ) to host these plasmid sets. The data in Table 2 demonstrate that expression of the vtpA-lacZ fusion in Top10 was not activated in the presence of V. cholerae hapR or V. tubiashii vtpR genes. Conversely, in O395N1ΔZ, expression of the vtpA-lacZ fusion was much stronger in the presence of the hapR or vtpR gene than in the vector control (Table 2). Moreover, expression of the vtpB-lacZ fusion was considerably induced in the presence of the vtpR gene in both E. coli and V. cholerae (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Expression of vtpA-lacZ, vtpB-lacZ, vthAB-lacZ, and vtpR-lacZ fusions in E. coli strain Top10 and V. cholerae strain O395N1ΔZ in the presence of hapR or vtpR

| Bacterial construct |

Mean β-galactosidase activity (Miller unit) ± SDa | |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | Plasmids | |

| Top10 | pBAD + pvtpA-lacZ | 91 ± 4 |

| pBAD-hapR + pvtpA-lacZ | 61 ± 8 | |

| pBAD-vtpR + pvtpA-lacZ | 69 ± 18 | |

| O395N1ΔZ | pBAD + pvtpA-lacZ | 209 ± 76 |

| pBAD-hapR + pvtpA-lacZ | 1,670 ± 152 | |

| pBAD-vtpR + pvtpA-lacZ | 1,710 ± 280 | |

| Top10 | pBAD + pvtpB-lacZ | 39 ± 2 |

| pBAD-hapR + pvtpB-lacZ | 1,029 ± 82 | |

| pBAD-vtpR + pvtpB-lacZ | 1,055 ± 124 | |

| O395N1ΔZ | pBAD + pvtpB-lacZ | 120 ± 53 |

| pBAD-hapR + pvtpB-lacZ | 953 ± 89 | |

| pBAD-vtpR + pvtpB-lacZ | 943 ± 130 | |

| Top10 | pBAD + pvthAB-lacZ | 45 ± 15 |

| pBAD-hapR + pvthAB-lacZ | 42 ± 23 | |

| pBAD-vtpR + pvthAB-lacZ | 39 ± 24 | |

| O395N1ΔZ | pBAD + pvthAB-lacZ | 52 ± 24 |

| pBAD-hapR + pvthAB-lacZ | 59 ± 8 | |

| pBAD-vtpR + pvthAB-lacZ | 60 ± 21 | |

| Top10 | pBAD + pvtpR-lacZ | 6,754 ± 1,435 |

| pBAD-hapR + pvtpR-lacZ | 1,764 ± 365 | |

| pBAD-vtpR + pvtpR-lacZ | 1,677 ± 436 | |

| O395N1ΔZ | pBAD + pvtpR-lacZ | 9,820 ± 1,204 |

| pBAD-hapR + pvtpR-lacZ | 2,239 ± 261 | |

| pBAD-vtpR + pvtpR-lacZ | 2,201 ± 497 | |

The values are means for three determinations.

The effects of VtpR on the hemolysin gene (vthAB) expression using a vthAB-lacZ fusion were assayed. The assay showed that expression of the vthAB-lacZ fusion was not induced by the presence of the vtpR in neither background (Table 2).

Lin et al. (30) previously documented that in V. cholerae HapR represses its own transcription. To test any autoregulatory mechanism in V. tubiashii vtpR expression, VtpR was expressed in combination with a vtpR-lacZ fusion. The data presented in Table 2 show that expression of the vtpR-lacZ fusion was much reduced in the presence of the vtpR or hapR gene in both background strains.

VtpR positively controls metalloprotease and hemolysin genes, whereas it represses its own expression in V. tubiashii.

To further investigate a role of VtpR in expression of metalloprotease and hemolysin genes in V. tubiashii, we compared the expression of vtpA-, vtpB-, and vthAB-lacZ fusions between the V. tubiashii wild-type and vtpR::cmR strains. Expression of the vtpA-lacZ and vtpB-lacZ fusions was >10-fold lower in the vtpR::cmR strain than in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4). Moreover, expression of vthAB-lacZ in the mutant was less than half of that in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4), confirming our earlier results that V. tubiashii VtpR activates both metalloprotease genes.

FIG. 4.

Comparison between V. tubiashii strain RE22 and the VtpR-deficient mutant in expression of vtpA, vtpB, and vthAB genes. Bacteria were grown in LB medium supplemented with 1% NaCl at 30°C, and samples were harvested at the late log (for vthAB-lacZ) and stationary phases and analyzed for β-galactosidase activities. The error bars of the Miller units indicate standard deviations (n = 3).

Effects of environmental factors on expression of the vtpA and vtpR genes.

We hypothesized that the effects of environmental factors on extracellular protease production (Fig. 1) are due to reduced expression of the vtpA or vtpR genes. To examine whether expression of these genes is affected by salinity as well as certain sugars, we compared the levels of the vtpA- and vtpR-lacZ fusions in V. tubiashii strain RE22. Table 3 shows that the expression of vtpA-lacZ was much reduced in the medium containing 5% NaCl compared to medium containing 1% NaCl. Moreover, the presence of glucose or sucrose, but not succinate, in minimal medium caused low vtpA-lacZ expression (Table 3). Similar changes to the vtpA-lacZ expression levels were observed in vtpR-lacZ expression levels under these different growth conditions (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effects of NaCl concentrations and carbon sources on expression of vtpA-lacZ and vtpR-lacZ fusions in V. tubiashii strain RE22

| Bacterial construct | Growth condition | Μean β-galactosidase activity (Miller unit) ± SDa |

|---|---|---|

| RE22(pvtpA-lacZ) | 1% NaCl | 3,248 ± 199 |

| 3% NaCl | 1,300 ± 68 | |

| 5% NaCl | 273 ± 49 | |

| RE22(pvtpR-lacZ) | 1% NaCl | 6,826 ± 1,071 |

| 3% NaCl | 2,994 ± 399 | |

| 5% NaCl | 1,206 ± 320 | |

| RE22(pvtpA-lacZ) | Succinate | 1,401 ± 276 |

| Glucose | 334 ± 31 | |

| Sucrose | 279 ± 58 | |

| RE22(pvtpR-lacZ) | Succinate | 5,146 ± 812 |

| Glucose | 1,564 ± 378 | |

| Sucrose | 1,594 ± 354 |

The values are means for three determinations.

DISCUSSION

We have observed that a secreted metalloprotease, VtpA, was shown to be a major toxic factor produced by V. tubiashii (19). Similar metalloproteases from other marine Vibrio species were also found to cause oyster larval mortalities (18). Due to the economic importance of vibriosis in shellfish hatcheries, it is of interest to investigate effects of environmental conditions on metalloprotease production in V. tubiashii. In this report, we showed that extracellular proteolytic activities are reduced at elevated temperatures, salinity, and the presence of sugars such as glucose and sucrose in V. tubiashii. This led us to further investigate the genetic mechanisms of metalloprotease regulation in this organism.

It has been well established that the TetR family of transcriptional regulators positively controls protease production in a variety of Vibrio species, including V. anguillarum (VanT), V. cholerae (HapR), V. harveyi (LuxR), and V. vulnificus (VvpR/SmcR) (5, 22, 23, 35, 39). Here, we report a V. tubiashii gene, vtpR, encoding a homolog of the TetR family transcriptional regulators. Our sequence analyses revealed that the VtpR protein showed significantly high homology with the TetR family of regulatory proteins from several Vibrio species including SmcR, LuxR, and HapR. The extensive study (8) revealed that HapR from V. cholerae possesses typical DNA-binding helix-turn-helix (HTH) motifs in the N-terminal region. We also observed the putative HTH motifs in the N-terminal region of VtpR, highly similar to other homologs from several other Vibrio species. Therefore, we anticipated that this protein is involved in regulation of the vtpA metalloprotease gene in V. tubiashii.

VtpR positively affected production of the extracellular hemolysin, VthA. It has been reported that production of an extracellular hemolysin (VvhA) is negatively regulated by SmcR in V. vulnificus (38). Unlike V. vulnificus, the V. tubiashii vtpR-deficient mutant expressed lower levels of the hemolysin genes vthAB at the late log phase of growth compared to the wild-type strain. These results suggested that VtpR positively controls hemolysin production.

Our recent observations (17, 19) revealed that the hemolytic activities of the V. tubiashii wild-type strain severely deteriorated at the stationary phase due to the high levels of protease production. Interestingly, hemolysin production by the vtpR::cmR strain was increased at the stationary phase, probably due to the absence of inhibitory activities of the VtpA metalloprotease (17). Also, other regulatory proteins, including CRP (for cyclic AMP receptor protein) and ToxR (2), in V. tubiashii might be involved in the activation of vthAB transcription, as documented that in V. vulnificus expression of the vvhAB operon is directly activated by CRP (4) as well as ToxR (27).

Although motility in the V. cholerae hapR mutant was comparable to that of the wild-type strain (49), in V. vulnificus an smcR mutant led to reduced motility (20). Our data demonstrated that the VtpR protein positively controls swimming motility. Thus, it appears that VtpR in V. tubiashii controls the bacterial motility similar to SmcR in V. vulnificus.

In the present study, we found an additional putative metalloprotease gene, vtpB in V. tubiashii, which appeared to be homologous to that from multiple Vibrio species. Although the VtpB protein contains some of features typically found in metalloproteases, VtpB is clearly distinct from the VtpA-type of metalloproteases in terms of size as well as amino acid sequence. It is interesting that V. splendidus, V. campbellii, and V. harveyi, all of which are known shellfish pathogens (14, 16, 44), carry homologs of vtpB, whereas other pathogenic Vibrio species do not. This correlation implies that the VtpB type of metalloproteases might play a role in shellfish diseases.

We observed that VtpR activated the vtpA gene when expressed in V. cholerae but not in E. coli. This difference might be due to additional factors present in V. cholerae that are absent in E. coli. Jeong et al. (22) reported that in V. vulnificus, CRP, IHF (for integration host factor), and RpoS were required for activation of a homolog of vtpA, vvpE. It is also documented that in V. cholerae, not only CRP and RpoS but also H-NS (The histone-like nucleoid structuring protein), as well as a yet-unidentified factor, is necessary to express the V. cholerae metalloprotease gene, hapA (41). Therefore, it is possible that these factors are involved in transcriptional regulation of the vtpA gene in V. tubiashii. On the other hand, VtpR activated the vtpB gene in the V. cholerae as well as E. coli backgrounds, indicating not only that the regulatory mechanism of vtpB is distinct from that of vtpA but that activation of the vtpB gene does not require other transcription factors than VtpR.

Expression data in V. tubiashii background further cemented the evidence that VtpR functions as an activator of both vtpA and vtpB. The reporter expression of both genes was severely reduced in the vtpR::cmR strain. These results, together with the β-galactosidase assays in E. coli and V. cholerae, strongly suggested that VtpR is responsible for expression of these genes in V. tubiashii. To our knowledge, this is the first report to establish that a single TetR family transcriptional regulator activates distinct secreted metalloproteases in Vibrio species.

Mutation of the vtpR gene resulted in much-reduced expression of the vthAB hemolysin genes in V. tubiashii, indicating that the VtpR protein positively controls transcript levels of vthAB, which correlates with our observations that the mutant produces much reduced levels of extracellular hemolysin compared to the wild-type strain. The reduction of the vthAB-lacZ expression in the mutant was not as dramatic as that of vtpA- or vtpB-lacZ, again implying additional factors that activate the vthAB gene expression.

The presence of VtpR severely diminished expression of the vtpR-lacZ fusion, indicating that VtpR interacts with its own promoter as an autorepressor. In V. cholerae, HapR represses transcription of the hapR gene by direct binding (30). Therefore, it is likely that the much-reduced expression of the vtpR-lacZ fusion by VtpR and HapR was due to direct binding. In general, these types of transcriptional regulators frequently affect large number of genes both positively and negatively (26, 36, 46). Thus, we expect VtpR to control a large variety of genes in V. tubiashii.

The severe reduction in protease production by the presence of glucose or sucrose correlated well with reduced production of vtpA in V. tubiashii. This was not surprising since these carbon sources are known to act as inhibitors of the vvpE and hapA genes in V. vulnificus (21) and V. cholerae (3, 39, 40), respectively. Therefore, it is likely that V. tubiashii possesses similar sugar-sensitive regulatory mechanisms. Moreover, CRP has been reported to positively regulate transcription of the hapR gene in V. cholerae (12, 28, 29). In the present study we observed strongly repressed expression of vtpR-lacZ fusion in the presence of these carbon sources. It is tempting to speculate that protease production is hierarchically controlled by CRP via VtpR in V. tubiashii.

In summary, we have demonstrated that in V. tubiashii the TetR-type transcriptional regulator, VtpR, positively controls production of multiple extracellular proteins, including the metalloproteases and hemolysins, as well as swimming motility (Fig. 5). Our observations suggested that while VtpR is directly involved in activation of at least two distinct metalloprotease genes, it positively affects a hemolysin gene. Our results also revealed that VtpR acts as an autorepressor. Furthermore, transcription of the vtpR gene is attenuated by elevated environmental conditions, which might, in turn, contribute to lower expression of the metalloprotease gene, leading to loss of proteolytic activities of the culture supernatants. Thus, VtpR appears to be a global regulator of various phenotypes and regulates potential virulence factors in V. tubiashii.

FIG. 5.

Model showing regulatory system by VtpR to control various potential virulence factors in V. tubiashii. Environmental factors including temperatures, NaCl concentrations, and carbon sources affect expression of the vtpA as well as vtpR genes. Although V. tubiashii VtpR positively controls vtpA, vtpB, vthAB, the regulator acts as an autorepressor. VtpR is directly responsible for the transcription of vtpA and vtpB genes, whereas vthAB transcription might be indirectly activated via other factors or require additional regulatory proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. A. Elston for providing the V. tubiashii strain. We thank Erin J. Lind and Dima N. Gharaibeh for excellent technical assistance.

This study was partially funded by grants from Oregon Sea Grant, USDA/CREES Animal Health and Diseases, and the Agricultural Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. S. Truhl. 1991. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 2.Beaubrun, J. J., M. H. Kothary, S. K. Curtis, N. C. Flores, B. E. Eribo, and B. D. Tall. 2008. Isolation and characterization of Vibrio tubiashii outer membrane proteins and determination of a toxR homolog. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:907-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benitez, J. A., A. J. Silva, and R. A. Finkelstein. 2001. Environmental signals controlling production of hemagglutinin/protease in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 69:6549-6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi, H. K., N. Y. Park, D. Kim, H. J. Chung, S. Ryu, and S. H. Choi. 2002. Promoter analysis and regulatory characteristics of vvhBA encoding cytolytic hemolysin of Vibrio vulnificus. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47292-47299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croxatto, A., V. J. Chalker, J. Lauritz, J. Jass, A. Hardman, P. Williams, M. Cámara, and D. L. Milton. 2002. VanT, a homologue of Vibrio harveyi LuxR, regulates serine, metalloprotease, pigment, and biofilm production in Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 184:1617-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delston, R. B., M. H. Kothary, K. A. Shangraw, and B. D. Tall. 2003. Isolation and characterization of zinc-containing metalloprotease expressed by Vibrio tubiashii. Can. J. Microbiol. 49:525-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Silva, R. S., G. Kovacikova, W. Lin, R. K. Taylor, K. Skorupski, and F. J. Kull. 2007. Crystal structure of the Vibrio cholerae quorum-sensing regulatory protein HapR. J. Bacteriol. 189:5683-5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elston, R. A., H. Hasegawa, K. L. Humphrey, I. K. Polyak, and C. C. Häse. 2008. Re-emergence of Vibrio tubiashii in bivalve shellfish aquaculture: severity, environmental drivers, geographic extent, and management. Dis. Aquat. Org. 82:119-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estes, R. M., C. S. Friedman, R. A. Elston, and R. P. Herwig. 2004. Pathogenicity testing of shellfish hatchery bacterial isolates on Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas larvae. Dis. Aquat. Org. 58:223-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fong, J. C. N., and F. H. Yildiz. 2008. Interplay between cyclic AMP-cyclic AMP receptor protein and cyclic di-GMP signaling in Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 190:6646-6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garland, C. D., G. V. Nash, C. E. Summer, and T. A. McMeekin. 1983. Bacterial pathogens of oyster larvae (Crassostrea gigas) in a Tasmanian hatchery. Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 34:483-487. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez-Gil, B., S. Soto-Rodríguez, A. García-Gasca, A. Roque, R. Vazquez-Juarez, F. L. Thompson, and J. Swings. 2004. Molecular identification of Vibrio harveyi-related isolates associated with diseased aquatic organisms. Microbiology 150:1769-1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hada, H. S., P. A. West, J. V. Lee, J. Stemmler, and R. R. Colwell. 1984. Vibrio tubiashii sp. nov., a pathogen of bivalve mollusks. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 34:1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hameed, A. S. S., P. V. Rao, J. J. Farmer, F. W. Hickman-Brenner, and G. R. Fanning. 1996. Characteristics and pathogenicity of Vibrio campbellii-like bacterium affecting hatchery reared Penaeus indicus (Milne Edwards, 1837) larvae. Aquat. Res. 27:853-863. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasegawa, H., and C. C. Häse. 2009. The extracellular metalloprotease of Vibrio tubiashii directly inhibits its extracellular hemolysin. Microbiology 155:2296-2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasegawa, H., D. N. Gharaibeh, E. J. Lind, and C. C. Häse. 2009. Virulence of metalloproteases produced by Vibrio species on Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) larvae. Dis. Aquat. Org. 85:123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasegawa, H., E. J., Lind, M. A. Boin, and C. C. Häse. 2008. The extracellular metalloprotease of Vibrio tubiashii is a major virulence factor for Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) larvae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4101-4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyun, L.-J., J.-E. Rhee, U. Park, H.-M. Ju, B.-C. Lee, T.-S. Kim, H.-S. Jeong, and S.-H. Choi. 2007. Identification and functional analysis of Vibrio vulnificus SmcR, a novel global regulator. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17:325-334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeong, H. S., K. C. Jeong, H. K. Choi, K.-J. Parks, K.-H. Lee, J. H. Rhee, and S. H. Choi. 2001. Differential expression of Vibrio vulnificus elastase gene in a growth phase-dependent manner by two different types of promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 276:13875-13880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong, H.-S., M.-H. Lee, K.-H. Lee, S.-J. Park, and S.-H. Choi. 2003. SmcR and cyclic AMP receptor protein coactivate Vibrio vulnificus vvpE encoding elastase through the RpoS-dependent promoter in a synergistic manner. J. Biol. Chem. 278:45072-45081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jobling, M. G., and R. K. Holmes. 1997. Characterization of hapR, a positive regulator of the Vibrio cholerae HA/protease gene hap, and its identification as a functional homologue of the Vibrio harveyi luxR gene. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1023-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keen, N. T., S. Tamaki, D. Kobayashi, and D. Trollinger. 1988. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 70:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kothary, M. H., R. B. Delston, S. K. Curtis, B. A. McCardell, and B. D. Tall. 2001. Purification and characterization of vulnificolysin-like cytolysin produced by Vibrio tubiashii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3707-3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, D. H., H. S. Jeong, H. G. Jeong, S. M. Kim, K. M. Kim, H. Kim, and S. H. Choi. 2008. A consensus sequence for binding of SmcR, a Vibrio vulnificus LuxR homologue and genome-wide identification of the SmcR regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 283:23610-23618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, S. E., S. H. Shin, S. Y. Kim, Y. R. Kim, D. H. Shin, S. S. Chung, Z. H. Lee, J. Y. Lee, K. C. Jeong, S. H. Choi, and J. H. Rhee. 2000. Vibrio vulnificus has the transmembrane transcription activator ToxRS stimulating the expression of the hemolysin gene vvhA. J. Bacteriol. 182:3405-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang, W., A. Pascual-Montano, A. J. Silva, and J. A. Benitez. 2007. The cyclic AMP receptor protein modulates quorum sensing, motility and multiple genes that affect intestinal colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 153:2964-2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang, W., A. J. Silva, and J. A. Benitez. 2007. The cyclic AMP receptor protein modulates colonial morphology in Vibrio cholerae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7482-7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin, W., G. Kovacikova, and K. Skorupski. 2005. Requirements for Vibrio cholerae HapR binding and transcriptional repression at the hapR promoter are distinct from those at the aphA promoter. J. Bacteriol. 187:3013-3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 32.Milton, D. L. 2006. Quorum sensing in vibrios: complexity for diversification. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296:61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyoshi, S., and S. Shinoda. 2000. Microbial metalloproteases and pathogenesis. Microbes. Infect. 2:91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyoshi, S., H. Wakae, K. Tomochika, and S. Shinoda. 1997. Functional domains of a zinc metalloprotease from Vibrio vulnificus. J. Bacteriol. 179:7606-7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mok, K. C., N. S. Wingreen, and B. L. Bassler. 2003. Vibrio harveyi quorum sensing: a coincidence detector for two autoinducers controls gene expression. EMBO J. 22:870-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pompeani, A. J., J. J. Irgon, M. F. Berger, M. L. Bulyk, N. S. Wingreen, and B. L. Bassler. 2008. The Vibrio harveyi master quorum-sensing regulator, LuxR, a TetR-type protein is both an activator and a repressor: DNA recognition and binding specificity at target promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 70:76-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saltikov, C. W., and D. K. Newman. 2003. Genetic identification of a respiratory arsenate reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:10983-10988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao, C. P., and L. I. Hor. 2001. Regulation of metalloprotease gene in Vibrio vulnificus by a Vibrio harveyi LuxR homologue. J. Bacteriol. 183:1369-1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silva, A. J., and J. A. Benitez. 2004. Transcriptional regulation of Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/protease by the cyclic AMP receptor protein and RpoS. J. Bacteriol. 186:6374-6382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva, A. J., K. Pham, and J. A. Benitez. 2003. Hemagglutinin/protease expression and mucin gel penetration in El Tor biotype Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 149:1883-1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva, A. J., S. Z. Sultan, W. Liang, and J. A. Benitez. 2008. Role of the histone-like nucleoid structuring protein in the regulation of rpoS and RpoS-dependent genes in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 190:7335-7345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sindermann, C. J. 1988. Vibriosis of larval oysters, p. 271-274. In C. J. Sindermann and D. V. Lightner (ed.), Disease diagnosis and control in North American aquaculture. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 43.Spaink, H. P., R. J. H. Okker, C. A. Wijffelman, E. Pees, and B. J. J. Lugtenberg. 1987. Promoters in the nodulation region of the Rhizobium leguminosarum Sym plasmid pRL1JI. Plant Mol. Biol. 9:27-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugumar, G., T. Nakai, Y. Hirata, D. Matsubara, and K. Muroga. 1998. Pathogenicity of Vibrio splendidus biovar II, the causative bacterium of bacillary necrosis of Japanese oyster larvae. Fish Pathol. 33:79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang, B., S. Nirasawa, M. Kitaoka, and K. Hayashi. 2002. The role of the N-terminal propeptide of the pro-aminopeptidase processing protease: refolding, processing, and enzyme inhibition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 296:78-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsou, A. M., T. Cai, Z. Liu, J. Zhu, and R. V. Kulkarni. 2009. Regulatory targets of quorum sensing in Vibrio cholerae: evidence for two distinct HapR-binding motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Tubiash, H. S., R. R. Colwell, and R. Sakazaki. 1970. Marine vibrios associated with bacillary necrosis, a disease of larval and juvenile bivalve mollusks. J. Bacteriol. 103:2721-2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoon, S.-S., and J. J. Mekalanos. 2006. 2,3-Butanediol synthesis and the emergence of the Vibrio cholerae El Tor biotype. Infect. Immun. 74:6547-6556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu, J., M. B. Miller, R. E. Vance, M. Dziejman, B. L. Bassler, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2002. Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3129-3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]