Abstract

Infection by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) is initiated by specific interactions between the SARS-CoV spike (S) protein and its receptor ACE2. In this report, we screened a peptide library representing the SARS-CoV S protein sequence using a human immunodeficiency virus-based pseudotyping system to identify specific regions that affect viral entry. One of the 169 peptides screened, peptide 9626 (S residues 217–234), inhibited SARS-CoV S-mediated entry of the pseudotyped virions in 293T cells expressing a functional SARS-CoV receptor (human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) in a dose-dependent manner (IC50 ∼ 11 μM). Alanine scanning mutagenesis was performed to assess the roles of individual residues within this region of S, which was previously uncharacterized. The effects included significant reductions in expression (K223A), viral incorporation (L218A, I230A, and N232A), and reduced viral entry (L224A, L226A, I228A, T231A, and F233A). Taken together, these results reveal a new region of the S protein that is crucial for SARS-CoV entry.

Abbreviations: SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; S, spike; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; hACE2, human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; RBD, receptor-binding domain; HR, heptad repeat

Keywords: viral entry, SARS-CoV, envelope, mutagenesis, spike

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a progressive pulmonary illness that was first reported from Guangdong Province, China, in 2003.1 A novel pathogenic coronavirus was identified as the causative agent of SARS.2, 3, 4 Highly transmissible SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) quickly spread from its origin in South China to more than two dozen countries in Asia, North and South America, and Europe. Within a few months, the infectious disease became a global emergency culminating to more than 8000 cases reported worldwide, of which 10% were fatal. Although the SARS outbreak of 2003 has been controlled, there is currently no specific therapeutic treatment available against SARS-CoV infection. Targeted drug discovery of molecules inhibiting SARS-CoV entry may offer the opportunity to counter SARS-CoV pathogenesis at a critical stage in the virus life cycle.

The spike (S) protein of SARS-CoV is a 1255-amino-acid, heavily glycosylated integral membrane protein, which, like other viral class I fusion proteins such as influenza HA, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) gp120/gp41, and Ebola GP, is trimeric in its native state and mediates entry into susceptible target cells.5, 6, 7, 8 The overall sequence homology between SARS-CoV S and other known CoV S proteins is low; however, the functional homology conveniently permits the differentiation of two distinct ectodomain regions heretofore known as S1 and S2. For some coronaviruses, the S protein is cleaved into these two subunits during maturation and transport to the cell surface;9, 10 however, this cleavage, as well as cleavage at other nearby sites, apparently occurs during or after entry in the case of SARS-CoV S.11, 12, 13 The S1 region is responsible for binding to the receptor, human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hACE2).14 In addition, molecules belonging to the L-SIGN family have been suggested as receptors for SARS-CoV entry.15 In the case of hACE2, a 193-amino-acid fragment within S1 has been identified as the minimum receptor-binding domain (RBD).16, 17, 18 The S2 region contains two characteristic motifs shared by all class I fusion proteins, heptad repeats 1 and 2 (termed HR1 and HR2), which are involved in subsequent fusion steps.6, 19 Interestingly, several studies have demonstrated that peptides derived from the HR2 motif can block SARS-CoV entry, presumably by binding to HR1 of S2 and thereby blocking formation of the “six-helix bundle”, in an analogous mechanism to that of HIV HR2.8, 19, 20

To date, most studies on SARS-CoV entry have been focused on the roles of the RBD in S1 and the HR1 and HR2 motifs in S2. In this report, using an HIV-based pseudotyping system, we have identified a small region within S1, distinct from the RBD, that inhibits SARS S-mediated entry when added exogenously and plays a critical role in SARS-CoV function. Elucidation of the role of this region in SARS-CoV entry may shed light on the entry mechanism of SARS-CoV and, moreover, aid in developing therapeutic treatments against SARS-CoV infection and pathogenesis.

In order to identify functionally important regions of SARS-CoV S, we used a SARS-CoV S/HIV pseudotyping system to determine whether peptides representing portions of the S protein might inhibit virus entry. For these experiments, HIV-SARS S pseudoparticles were produced by co-transfecting 293T cells with SARS-CoV S DNA and an HIV vector containing the luciferase reporter gene. The pseudotyped virions were used to challenge 293T cells transiently transfected with hACE2 DNA. At 2 days post-transduction, luciferase accumulations provided readouts of S protein-mediated viral entry. 293T cells, previously reported to have endogenous hACE2,16 supported S pseudotyped virus entry, with a luciferase activity 100-fold higher than that obtained by transduction with non-pseudotyped HIV cores. Transfection with hACE2 increased susceptibility to HIV-SARS S an additional 100-fold (or > 104 higher than background, data not shown); thus, all subsequent studies used cells transfected with hACE2. We further noted that the luciferase levels of the cells infected by the S pseudotyped virions increased as more hACE2 DNA was used in the transfection, while the luciferase levels of the cells infected by the VSV-G pseudotyped virions, which utilize a different receptor and are used as controls, were not affected (data not shown).

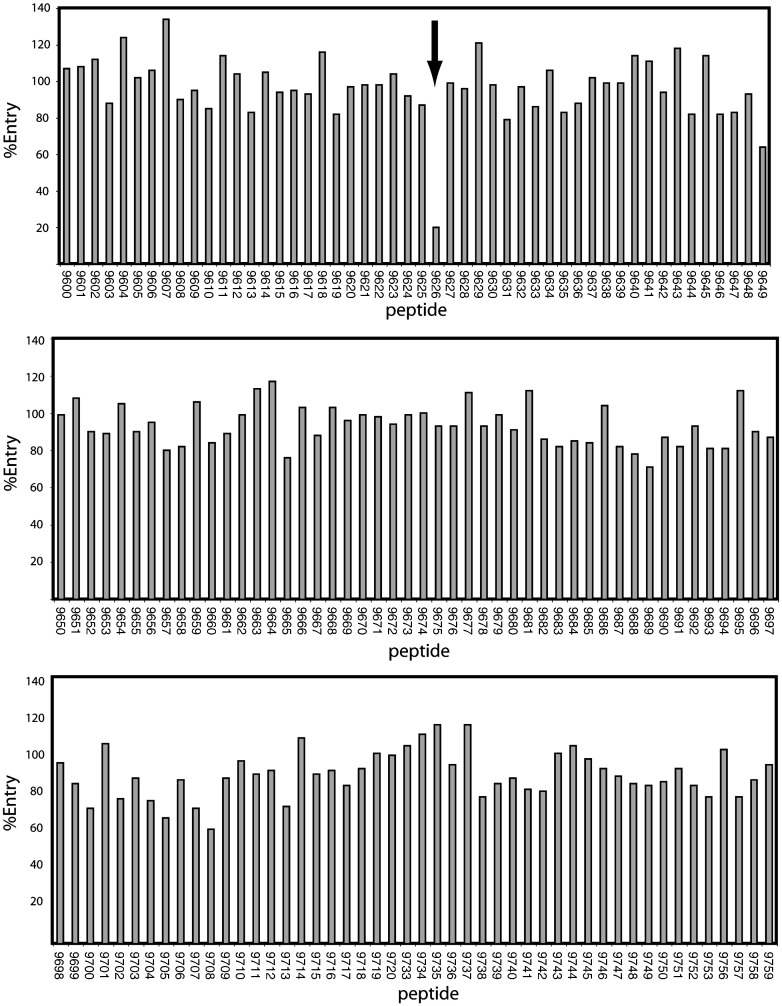

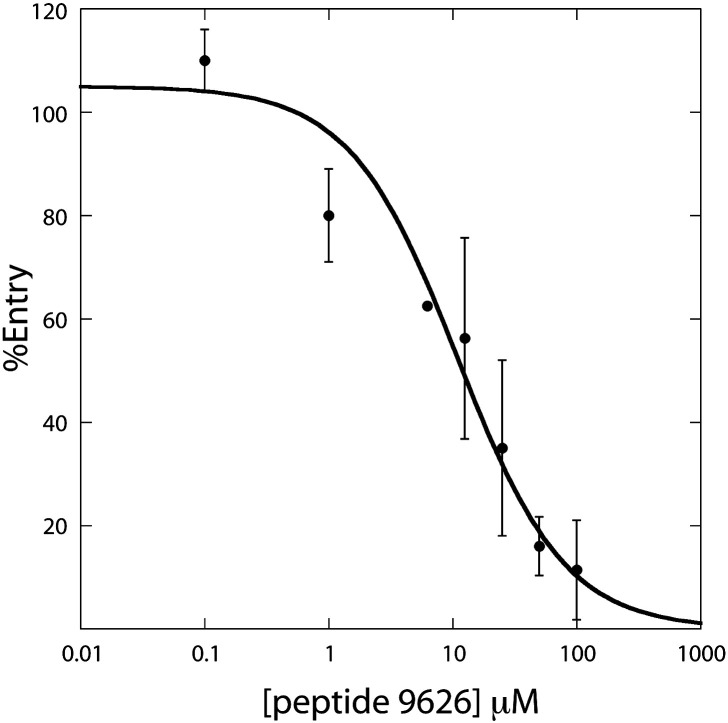

One hundred sixty-nine peptides, which together represent overlapping regions of the entire S protein,21, 22 were individually screened for their effects on transduction. In each case, the peptides were incubated with the diluted pseudotyped virions at a final peptide concentration of 50 μM, mixtures were then incubated with the 293T-ACE2 transfectants, media were changed after 16 h, and the luciferase activities were determined 2 days later. Among the 169 peptides analyzed, only peptide 9626 (sequence = TLKPIFKLPLGINITNFR) was able to block entry of the S/HIV virions into the target cells by ∼ 80% at a concentration of 50 μM (Fig. 1 ). Seven other peptides (peptides 9649, 9665, 9689, 9700, 9705, 9708, and 9713) blocked S pseudotyped viral entry into 293T-hACE2 cells by up to 40% at a concentration of 50 μM in the initial screen (Fig. 1); however, none of these peptides showed a dose-dependent inhibition on viral entry in the second-round screening. Thus, only peptide 9626 was considered for further analysis. As shown in Fig. 2 , when 293T cells transiently transfected with hACE2 were used as target cells, a dose-dependent inhibition by peptide 9626 on viral entry was observed with an IC50 of ∼ 11 μM. Under the identical conditions, recombinant S2-HR2 protein purified from Escherichia coli gave an IC50 value greater than 50 μM.8 Interestingly, peptides screened in the present study that correspond to S2-HR2 sequence were not inhibitory, presumably due to their relatively small size with respect to recombinant S2-HR28 (18 residues versus 53 residues, respectively). In contrast, peptide 9626 is a significantly better entry inhibitor than S2-HR2; however, in contrast to S2-HR2, the mechanism of inhibition is currently unknown. For example, the peptide could presumably inhibit entry by binding to S, hACE2, or an unknown co-receptor. Finally, it is important to note that peptide 9626 is a relatively poor entry inhibitor with respect to peptides based on the HIV HR2 sequence, which exhibit IC50 in the low nanomolar range.23

Fig. 1.

Effect of S peptides in SARS-CoV S-mediated entry. A peptide library of S protein sequence consisting of 169 peptides total was obtained from National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. Each peptide is 16–18 amino acids in length with 10 amino acids overlapping with the preceding peptide.21, 22 Peptides were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline without Ca2+ or Mg2+ to a final concentration of 1 mM. To examine the effect of each peptide on SARS-CoV entry, we incubated each peptide with the pseudotyped virions possessing codon-optimized S14 at a final concentration of 50 μM at room temperature for 15 min. The mixture was then added to the 293T cells transiently transfected with codon-optimized hACE214 in 24-well plates and incubated for 16 h at 37 °C. Fresh media were added to the cells 16 h postinfection. The cell lysates were analyzed for luciferase activity 48 h postinfection. The arrow denotes inhibition observed by peptide 9626, which exhibited the best inhibition.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the effects of peptide 9626 on SARS-CoV S-mediated entry. Peptide 9626 (TLKPIFKLPLGINITNFR) was synthesized by the Protein Research Resources Laboratory of the Research Resources Center (University of Illinois at Chicago). The peptide was preincubated with 1/8 diluted S pseudotyped virions at room temperature for 15 min at the indicated concentrations prior to infection of 293T cells transiently transfected with hACE2 (10 μg plasmid/100 mm plate). Cell lysates were collected 48 h postinfection and measured for luciferase activity. The curve represents a fit to the equation %entry = 100/(1 + [peptide]/IC50). Error bars represent the standard deviations of three separate experiments performed from transfection to luciferase detection. Note that no inhibitory effects were observed for VSVG/HIV entry at a peptide concentration of 50 μM.

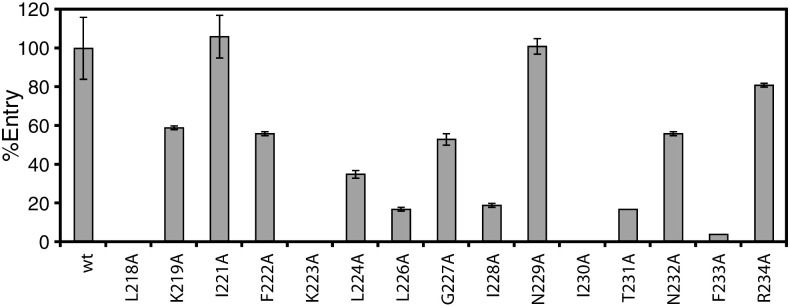

To further explore the role of S protein residues 217–234, which correspond to the sequence of peptide 9626, in viral entry, we generated a deletion mutant of this region (Δ9626) and 15 alanine substitution mutants of individual residues within this region. Each of these mutants was characterized for protein expression, incorporation into HIV virions, and ability to mediate viral entry. The results are shown in Fig. 3 and summarized in Table 1 . Mutant Δ9626 was expressed normally in 293T cells, as determined by Western blot; however, it could not be detected on HIV virions, and thus, it was completely defective in mediating viral entry in 293T-hACE2 (Table 1). Among the 15 substitution mutants of the S protein, mutant K223A disrupted expression (or, alternatively, stability) and mutants L218A, I230A, and N232A disrupted incorporation into virions, and thus, they were impaired or unable to mediate efficient viral entry (Fig. 3; Table 1). These results suggest that deletion of the peptide 9626 region or these four individual substitutions result in structural alterations of S, which adversely affected its oligomerization, transport to cell surfaces, accumulation at HIV budding sites, and/or stability. In contrast, the remaining 11 mutants did not adversely affect protein accumulation or viral incorporation (Table 1), suggesting that these mutations did not grossly disrupt the overall native conformation of the S protein. Interestingly, mutants L226A, I228A, T231A, and F233A, and to a less extent, mutant L224A, were defective in mediating efficient viral entry (Fig. 3; Table 1). In contrast, the remaining 6 mutants (K219A, I221A, F222A, G227A, N229A, and R234A) exhibited comparable entry to the wild-type S protein (defined as supporting > 50% of entry with respect to the wild-type). Taken together, these results demonstrate that residues 217–234 of S play critical roles in S structure and in mediating efficient viral entry.

Fig. 3.

Entry effects of alanine substitution mutants of the S protein. Entry of the mutated 1/8 diluted S pseudotyped viruses into 293T cells transiently transfected with hACE2 (10 μg/100 mm plate) measured by luciferase activities. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three separate experiments performed from transfection to luciferase detection.

Table 1.

Summary of SARS-CoV S mutants

| Mutanta | Entry (%)b | Expressionc | Incorporationc |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt | 100 ± 16 | +++ | +++ |

| Δ9626 | 0 ± 0 | +++ | – |

| L218A | 0 ± 0 | +++ | – |

| K219A | 59 ± 1 | +++ | +++ |

| I221A | 106 ± 11 | +++ | +++ |

| F222A | 56 ± 1 | +++ | +++ |

| K223A | 0 ± 0 | – | – |

| L224A | 35 ± 2 | +++ | +++ |

| L226A | 17 ± 1 | +++ | +++ |

| G227A | 53 ± 3 | +++ | +++ |

| I228A | 19 ± 1 | +++ | +++ |

| N229A | 101 ± 4 | +++ | +++ |

| I230A | 0 ± 0 | +++ | – |

| T231A | 17 ± 0 | +++ | +++ |

| N232A | 56 ± 1 | +++ | + |

| F233A | 4 ± 0 | +++ | +++ |

| R234A | 81 ± 1 | +++ | +++ |

Deletion and alanine substitution mutants of the S protein were generated by two-step PCR using HiPFU (Stratagene Inc.). The mutations were confirmed by sequencing the full-length S gene (Urbani Strain). T217 was not substituted with alanine because it is the first residue of the peptide sequence; P220 and P225 were not substituted with alanine because the substitution was deemed too radical of a change.

HIV pseudotyped virions with SARS-CoV S protein were produced by co-transfecting the cDNAs of wild type or mutant S genes with an envelope-deficient HIV vector (pNL4-3-Luc-R−E−24, 25) into 293T cells (producer cells) by a modified Ca3(PO4)2 method.26

The expression of the S protein in producer cells (293T) and its incorporation into the HIV virions were analyzed by Western blot using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the HR2 region generated in this study. Briefly, the coding region of the HR2 domain (HTSPDVDLGDISGINASSVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQELGKYEQYIK) was PCR-amplified using the full-length wild-type SARS-CoV S cDNA as the template. The amplified DNA fragment was digested with restriction endonucleases, cloned into pGEX-4T-1 (Amersham Biosciences), and confirmed by DNA sequencing. HR2 protein was expressed in E. coli strain BL21 as glutathione S-transferase fusion protein and purified using a glutathione affinity column following a previous protocol.27 Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against HR2 region were generated using HR2-glutathione S-transferase as the antigen (Animal Pharm).

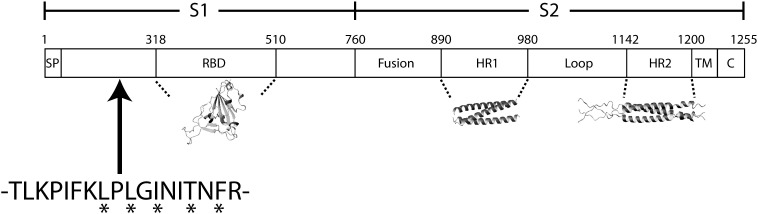

The SARS-CoV S protein, which contains more than 1200 amino acids in length, like the S proteins of other coronaviruses,9 is among the largest class I fusion proteins of enveloped viruses. Based on the knowledge of S proteins from other coronaviruses, as well as other viral glycoproteins, previously reported studies on the SARS-CoV S-mediated viral entry have been largely focused on three distinct regions or domains: the RBD of S1 (ACE2-binding region) and the heptad repeats HR1 and HR2 of S2. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 4, structures have been determined for each of these domains.7, 28, 29 In this report, we have provided evidence to demonstrate that S1 residues 217–234, which are distinct from the RBD, play important roles in S function. The importance of this region was initially implicated by screening of an overlapping library of peptides corresponding to SARS-CoV S protein using an HIV-based pseudotyping system and subsequently demonstrating dose-dependent inhibition by one peptide with an IC50 ∼ 11 μM (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 4, the region corresponding to peptide 9626 is approximately 90 amino acids N-terminal to the hACE2 binding domain.16 One possibility is that this region plays a structural role in proper folding and overall conformation of the S protein, and thus, the observed effects are indirect. However, this is unlikely because many of the substitution mutations within this region did not adversely affect S protein expression in the cells or incorporation into virions (Table 1), suggesting that the overall conformation of the S protein was not greatly altered. On the contrary, we envision that this region or domain of the S protein plays an active role in receptor-binding and/or post-binding steps of SARS-CoV entry. For example, this region of S1 may directly interact with the RBD to modulate binding between the S protein and hACE2, although the X-ray structure of the SARS-CoV RBD in complex with the hACE2 peptidase domain27 argues against this interpretation. Alternatively, this region may interact with other regions of S (e.g., S2 heptad repeats) to influence the membrane fusion process in viral entry. Finally, this region of the S protein could be involved in interactions with a different surface molecule other than hACE2 in mediating SARS-CoV entry. Elucidation of the exact role of this region or domain in S protein function should reveal mechanistic insights into SARS-CoV entry and further aid in the design of novel therapeutic treatments against SARS-CoV infection and pathogenesis.

Fig. 4.

Location of newly characterized region with respect to well-characterized SARS-CoV S domains. Residues that exhibit the largest effects on viral entry are denoted by asterisks. The structures shown for the RBD, HR1, and HR2 were taken from Refs. 28, 29 and 7 respectively.

Acknowledgements

We thank Balaji Manicassamy for critical reading of the manuscript. Reagents pNL4-3.Luc.R-E and the SARS-CoV S peptide set were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. The research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA 092459 (to L.R.). L.R. was a recipient of the Schweppe Foundation Career Development Award.

Edited by J. Karn

References

- 1.Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Goldsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drosten C., Günther S., Preiser W., van der Werf S., Brodt H.R., Becker S. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marra M.A., Jones S.J., Astell C.R., Holt R.A., Brooks-Wilson A., Butterfield Y.S. The Genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rota P.A., Oberste M.S., Monroe S.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmons G., Reeves J.D., Rennekamp A.J., Amberg S.M., Piefer A.J., Bates P. Characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) spike glycoprotein-mediated viral entry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4240–4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306446101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tripet B., Howard M.W., Jobling M., Holmes R.K., Holmes K.V., Hodges R.S. Structural characterization of the SARS-coronavirus spike S fusion protein core. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:20836–20849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400759200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakansson-McReynolds S., Jiang S., Rong L., Caffrey M. The solution structure of the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus heptad repeat 2 in the prefusion state. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:11965–11971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601174200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McReynolds S., Jiang S., Ying G., Celigoy J., Schar C., Rong L., Caffrey M. Characterization of the prefusion and transition states of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus S2-HR2. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6802–6808. doi: 10.1021/bi800622t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher T.M., Buchmeier M.J. Coronavirus spike proteins in viral entry and pathogenesis. Virology. 2001;279:371–374. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navas-Martin S., Weiss S.R. SARS: lessons learned from other coronaviruses. Viral Immunol. 2003;16:461–474. doi: 10.1089/088282403771926292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simmons G., Reeves J., Rennekamp A., Amberg S., Piefer A, Bates P. Characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS CoV) spike glycoprotein-mediated viral entry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4240–4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306446101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang I., Bosch B., Li F., Li W., Lee K., Ghiran S. SARS coronavirus, but not human coronavirus NL63, utilizes cathepsin L to infect ACE2-expressing cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;281:3198–3203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508381200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belouzard S., Chu V.C., Whittaker G.R. Activation of the SARS coronavirus spike protein via sequential proteolytic cleavage at two distinct sites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5871–5876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809524106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeffers S.A., Tusell S.M., Gillim-Ross L., Hemmila E.M., Achenbach J.E., Babcock G.J. CD209L (L-SIGN) is a receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15748–15753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403812101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babcock G.J., Esshaki D.J., Thomas W.D., Ambrosino D.M. Amino acids 270 to 510 of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein are required for interaction with receptor. J. Virol. 2004;78:4552–4560. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4552-4560.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong S.K., Li W., Moore M.J., Choe H., Farzan M.A. A 193-amino acid fragment of the SARS coronavirus S protein efficiently binds angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3197–3201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao X., Chakraborti S., Dimitrov A.S., Gramatikoff K., Dimitrov D.S. The SARS-CoV S glycoprotein: expression and functional characterization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;312:1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S., Xiao G., Chen Y., He Y., Niu J., Escalante C.R. Interaction between heptad repeat 1 and 2 regions in spike protein of SARS-associated coronavirus: implications for virus fusogenic mechanism and identification of fusion inhibitors. Lancet. 2004;363:938–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15788-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosch B.J., Martina B.E., Van Der Zee R., Lepault J., Haijema B.J., Versluis C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection inhibition using spike protein heptad repeat-derived peptides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8455–8460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400576101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guillén J., Pérez-Berná A.J., Moreno M.R., Villalaín J. Identification of the membrane-active regions of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike membrane glycoprotein using a 16/18-mer peptide scan: implications for the viral fusion mechanism. J. Virol. 2005;79:1743–1752. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1743-1752.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sui J., Li W., Roberts A., Matthews L.J., Murakami A., Vogel L. Evaluation of human monoclonal antibody 80R for immunoprophylaxis of severe acute respiratory syndrome by an animal study, epitope mapping, and analysis of spike variants. J. Virol. 2005;79:5900–5906. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.5900-5906.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qian K., Morris-Natschke S., Lee K. HIV entry inhibitors and their potential in HIV therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2009;29:369–393. doi: 10.1002/med.20138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connor R.I., Chen B.K., Choe S., Landau N.R. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology. 1995;206:935–944. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He J., Choe S., Walker R., Di Marzio P., Morgan D.O., Landau N.R. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J. Virol. 1995;69:6705–6711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6705-6711.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rong L., Bates P. Analysis of the subgroup A avian sarcoma and leukosis virus receptor: the 40-residue, cysteine-rich, low-density lipoprotein receptor repeat motif of Tva is sufficient to mediate viral entry. J. Virol. 1995;69:4847–4853. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4847-4853.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Y., Yu X., Rihani K., Wang Q.Y., Rong L. The role of a conserved acidic residue in calcium-dependent protein folding for a low density lipoprotein (LDL)-A module: implications in structure and function for the LDL receptor superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16629–16637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400157200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li F., Li W., Farzan M., Harrison S.C. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309:1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng Y., Liu J., Zheng Q., Yong W., Lu M. Structures and polymorphic interactions of two heptad-repeat regions of the SARS virus S2 protein. Structure. 2006;14:889–899. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]