Abstract

A subset of retinal ganglion cells has recently been discovered to be intrinsically photosensitive, with melanopsin as the pigment. These cells project primarily to brain centers for non-image-forming visual functions such as the pupillary light reflex and circadian photoentrainment. How well they signal intrinsic light absorption to drive behavior remains unclear. Here we report fundamental parameters governing their intrinsic light responses and associated spike generation. The membrane density of melanopsin is 104-fold lower than that of rod and cone pigments, resulting in a very low photon-catch and a phototransducing role only in relatively bright light. Nonetheless, each captured photon elicits a large and extraordinarily prolonged response, with a unique shape among known photoreceptors. Remarkably, like rods, these cells are capable of signalling single-photon absorption. A flash causing a few hundred isomerized melanopsin molecules in a retina is sufficient for reaching threshold for the pupillary light reflex.

In mammals, non-image-forming vision operates alongside conventional image-forming vision and drives processes such as the pupillary light reflex and circadian photoentrainment1. It is mediated largely by the intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs)2–5, which transmit signals from rods and cones but also are photoreceptors themselves – indeed, the only other known photoreceptors in mammals besides rods and cones6. IpRGCs express the pigment melanopsin3,7–13 and depolarize to light2, opposite to rods and cones but similar to most invertebrate photoreceptors. They are also less photosensitive than rods and cones14,15. Much fundamental information remains outstanding for these unique cells. First, their melanopsin content, which determines photon catch and therefore sensitivity, is unknown. The pigment content is difficult to measure biochemically or spectroscopically16 because ipRGCs are sparse (~700 per mouse retina3), but it can be evaluated electrophysiologically if the response to a single absorbed photon is measurable. Second, the properties of this “single-photon response” are unknown. This unitary response is the building block of all light responses, with its amplitude reflecting the signal amplification and its kinetics the phototransduction time course. Defining the single-photon-response kinetics is particularly important given the supposed bistability of melanopsin9,11,12,17–19, whereby photon absorption by active melanopsin can revert it to the inactive state. Bistability can therefore terminate the photoresponse prematurely if two photons in the same stimulus are absorbed sequentially by the same melanopsin molecule. This complication is avoided for single-photon responses, thus revealing the full forward-phototransduction kinetics. Finally, the efficiency of signalling intrinsic light absorption by the ipRGCs is unknown. Unlike rods and cones, ipRGCs signal via spikes, so spike threshold can potentially limit sensitivity. We address all of these questions in this study.

Flash sensitivity of ipRGCs

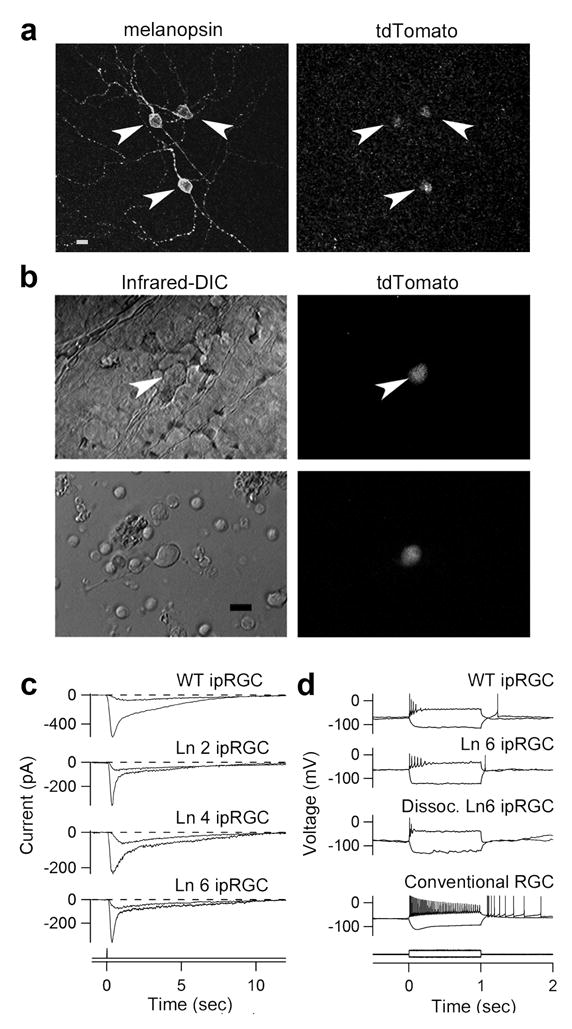

To identify the sparse ipRGCs, we generated BAC-transgenic mice20 expressing the fluorescent protein, tdTomato21 (λmax of 554 nm, far from 480 nm for melanopsin2,10,22,23), under the melanopsin promoter (Supplementary Information S1 and Fig. S1). The labelling was specific, and ipRGC properties seemed unaffected by tdTomato expression (Fig. 1; also Supplementary Information S1). We used perforated-patch recording, which avoided washout of the photoresponse observed in whole-cell recording2, 24, 25 (Supplementary Information S1), to make voltage-clamp measurements of current from in situ ipRGCs in flat-mount retinas (with synaptic blockers to eliminate rod and cone signals) or from dissociated cells.

Figure 1.

IpRGCs of melanopsin-tdTomato transgenic mice. a, Stacked confocal view of ipRGCs (transgenic line 6 (Ln 6); Supplementary Information S1) in flat-mount transgenic retina, showing melanopsin immunoreactivity and tdTomato fluorescence. b, Top panels: live in situ (Line 6) tdTomato cell in flat-mount retina (inner limiting membrane overlying cell removed); bottom panels: live, dissociated tdTomato cell. Infrared-DIC (left) and tdTomato fluorescence (right). c, Whole-cell or perforated-patch recordings of intrinsic photoresponses to dim and bright flashes (at time 0) from in situ wild-type ipRGCs (retrograde-labelled from the suprachiasmatic nucleus) and tdTomato ipRGCs of three transgenic lines (Lines 2, 4 and 6). 50-ms flash. −80 mV holding voltage. d, Responses to current injection recorded from retrograde-labeled wild-type ipRGC, in situ and dissociated tdTomato ipRGCs (Line 6), and conventional RGC retrograde-labelled from optic chiasm. Current monitor below. Steady injected current gave ~ −70 mV resting voltage and stimulus currents adjusted to give similar membrane polarization for all cells. 23°C. Synaptic blockers present for in situ cells. 10-μm scale bars in a and b.

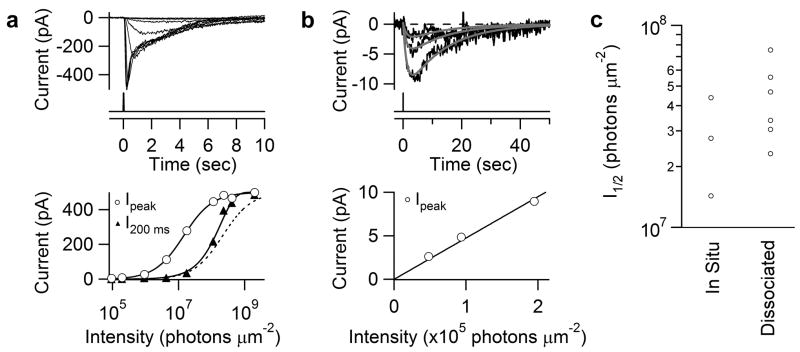

A brief flash (one in which intensity and duration are interchangeable without affecting the response26–28) of increasing intensity elicited a transient inward current of progressively larger amplitude and shorter time-to-peak, the latter indicating light adaptation27,29 (Fig. 2a, upper panel; in situ cell, diffuse light covering the entire dendritic field). As with rods and cones, the Michaelis equation fit the peak intensity-response relation 22,27 (open circles in Fig. 2a, lower panel) but has no simple mechanistic interpretation because the time-to-peak changes with flash intensity27,30. The “instantaneous” intensity-response relation measured at a fixed time in the response rising phase26,30 followed roughly a saturating-exponential function (filled triangles in Fig. 2a, lower panel), similar to rods30. One interpretation, albeit not unique, is that an active melanopsin molecule activates a spatially restricted domain within which transduction essentially saturates30. In any case, the intensity-response relation had a linear foot, i.e., the dim-flash responses had an invariant waveform and summed arithmetically (Fig. 2b; verified in 51 in situ and 13 dissociated cells), suggesting that the underlying single-photon response might be deducible from fluctuation analysis (see below).

Figure 2.

Intensity-response relations of ipRGCs. a, Top, responses of an in situ tdTomato-labeled cell to diffuse 50-ms flashes at different intensities. Light monitor below. 480 nm except for brightest 3 flashes, which were white but converted to equivalent 480-nm light (Methods). Bottom, intensity-response relations plotted from Top. Open circles, peak response-intensity relation fit with Michaelis equation, R = RmaxI / (I+ I1/2), with Rmax = 500 pA and I1/2 = 1.8 ×107 photons μm−2; filled triangles, instantaneous intensity-response relation at 200 ms from flash onset, fit with a saturating-exponential function, 1-e−I/Io, with Io=2.1 × 108 photons μm−2. Dashed curve: Michaelis fit aligned for comparison with saturating-exponential fit. b, Top, three smallest (dim-flash) responses from a, elicited by successive approximate doublings of flash intensity, on expanded ordinate and longer time base). Fits are A(e−t/1.3-e−t/12.9) with A = −12.2, −5.9 and −3.0, respectively (see Fig. 4a), according to the relative flash intensities. Bottom, peak intensity-response relation from Top, fit with straight line through the origin to indicate linearity. c, Collected I1/2. For in situ cells, I1/2 measured as in a. For dissociated cells, I1/2 calculated from dim and saturated responses based on Michaelis equation. All diffuse illumination. Perforated-patch recording. −80 mV holding voltage. 23°C. Synaptic blockers present for in situ cells.

The diffuse 480-nm flash intensity (I1/2) that half-saturated the photoresponse was similar for in situ cells (2.9±1.4 × 107 photons μm−2, mean±SD, 3 cells) and dissociated cells (comprising mainly soma, 4.4±1.9 × 107 photons μm−2, 6 cells) (Fig. 2c), suggesting comparable sensitivities of soma and dendrites, and no ill-effect of the dissociation procedure. The variation in I1/2 values could reflect sub-populations of ipRGCs with different sensitivities23,31 (we targeted small cells, with brighter tdTomato fluorescence). These I1/2 values are ~106 times that of mouse rods32 and ~104 times that of mouse cones33.

Single-photon response

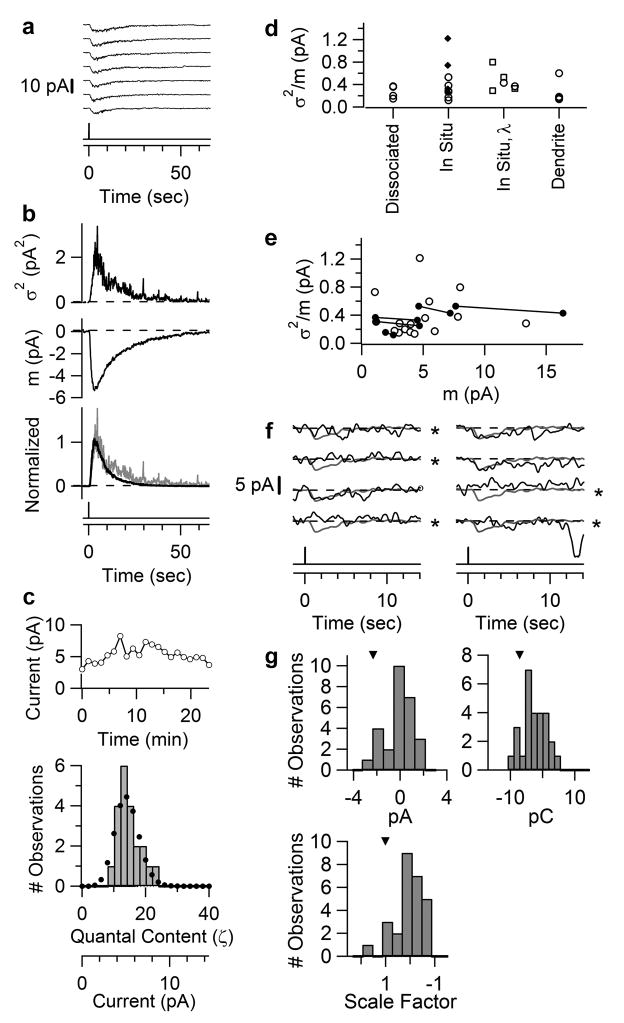

To determine if the low sensitivity of ipRGCs came from a low amplification in phototransduction, we estimated the single-photon response by fluctuation analysis34. We illuminated an ipRGC with repeated, identical flashes in the linear range (Fig. 3a; dissociated cell, diffuse light; complete response trials in Supplementary Fig. S2) and computed the response ensemble mean, m(t), and variance, σ2(t) (Fig. 3b, middle and top panels). The time courses of m2(t) and σ2(t) were similar (Fig. 3b, bottom panel), not inconsistent with trial-to-trial fluctuations arising predominantly from stochastic variations in the number of absorbed photons, with each photon giving a stereotypic unitary response. Recording stability (Fig. 3c, upper panel) allowed the fluctuations to be quantified, with the σ2/m ratio at response peak giving a unitary amplitude of 0.4 pA. As expected, the measured amplitude histogram broadly fit the Poisson distribution predicted from this σ2/m value (Fig. 3c, lower panel) (Methods). From four dissociated cells with diffuse light, σ2/m was 0.3±0.1 pA (mean±SD). In situ cells stimulated with a 40- or 100-μm light spot centred on the soma gave a similar σ2/m of 0.4±0.3 pA (10 cells), as did dendritic stimulation with a 40-μm spot centred at 100 μm from the soma (σ2/m = 0.3±0.2 pA, 4 cells) (Fig. 3d). 620- or 420-nm light produced the same σ2/m as well (Fig. 3d). Some dispersion in the σ2/m value was likely due to the limited number of trials achievable. As expected, σ2/m was independent of m within the linear range (Fig. 3e, 5 cells).

Figure 3.

Single-photon response of ipRGCs. a–e, Fluctuation analysis of dissociated ipRGC at 23°C; f–g, Directly resolved single-photon response from in situ ipRGC at 35 °C. a, Partial series of responses to identical dim flashes (full series in Supplementary Fig. S2). 50-ms, 480-nm diffuse flash delivering 6.2×106 photons μm−2. b, Top and middle, response ensemble variance, σ2(t), and mean, m(t). Bottom, overlaid and scaled σ2(t) and m2(t) showing similar waveforms. c, Top, response amplitudes over time to indicate stationarity. Bottom, amplitude histogram (bars). Dotted profile is Poisson distribution from ζ = m2/σ2 = 13.5 (Methods). d, Collected σ2/m values. Respectively, diffuse light for “dissociated”; 40-μm spot (filled diamonds) and 100-μm spot (open circles) for “in situ”; 100-μm spot at 620 nm (left open squares) or 620 nm/420 nm compared for a given cell (paired square/circle on middle and right) for “in situ, λ”; 40-μm spot at 100 μm from soma for in situ “dendrite”. e,σ2/m values from d plotted against m. Same-cell measurements connected by lines. f, Partial series of responses of an in situ ipRGC to identical flashes (full series in Supplementary Fig. S3), mostly too dim to elicit a response. 35 °C. 8.2 × 105 photons μm−2 at 480 nm, 40-μm spot. Single-photon response from σ2/m was 2.3 pA. Grey trace superimposed on each trial (black trace) is the mean response to a dim flash 4-fold brighter (for better resolution) and scaled to 2.3 pA, thus representing the expected profile of the unitary response. Apparent failures marked by “*” judged according to three detection algorithms (Supplementary Information S1). g, Histograms from complete trial series based on the algorithms over a ~2-sec window capturing the peak of the expected unitary-response profile. Arrowheads indicate the respective parameters of expected unitary profile.

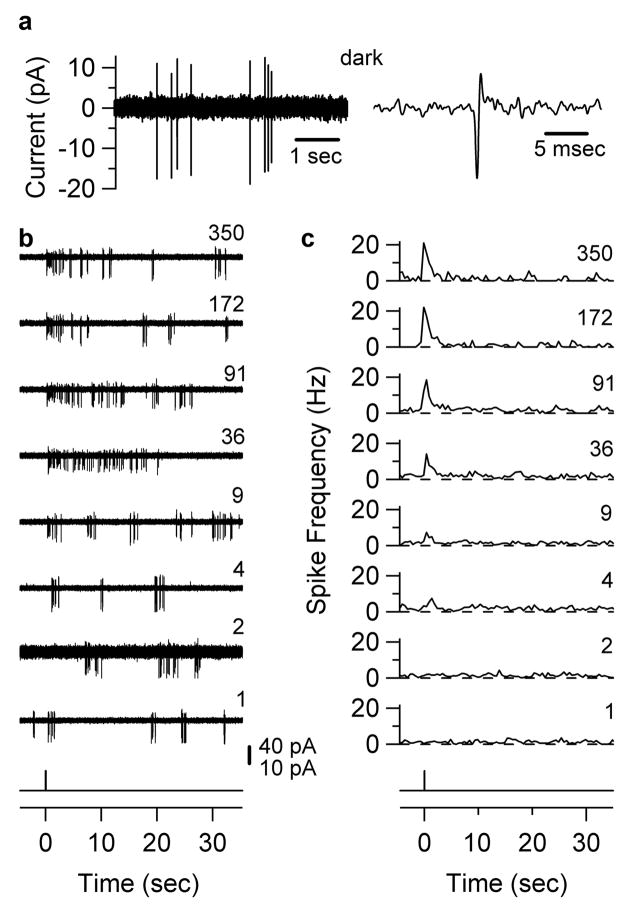

Figure 5.

Flash threshold for modulation of ipRGC spike frequency. Loose-patch recordings from an in situ ipRGC at 35° C. a, Left, spontaneous firing in darkness. Right, a single spike from Left on expanded abscissa. b, Effect of different-intensity flashes (50 msec, 480 nm, 40-μm diameter spot centered on soma). Flash monitor at bottom. Relative flash intensity indicated on right of each trace. 40-pA scale bar for all traces except relative intensity “2,” where it is 10 pA due to a transient decrease in contact resistance with the cell. c, Peri-stimulus time histograms for flash intensities in b. 4–15 trials averaged, 500-ms bins. Threshold modulation of spike frequency occurs at relative flash intensity “4,” or 1.9 × 104 photons μm−2.

To support the above analysis, we tried to observe the single-photon response directly by using a flash so dim that most trials elicited no response or just one unit. We experimented at 35°C, which made the dim-flash responses faster and larger by ~3-fold (see below and Fig. 4b), though stable recordings were rare. The light response showed all-or-none behaviour, with a high probability of failure (black traces in Fig. 3f; in situ ipRGC, local 40-μm spot on soma; only partial series shown, see Supplementary Fig. S3 for complete trials). In Fig. 3f, the unitary amplitude from σ2/m was 2.3 pA. The grey traces give the expected unitary-response profile (see legend). Comparing this profile to each response yielded the apparent failures (indicated by *) and uncertain failures (absent in trials shown, see Supplementary Information S1 for detections based on criteria of current, charge, and a least-squares fit, respectively). Some responses matched the profile well, suggesting that they were singletons. The mean number of unitary responses per flash (i.e., the mean “quantal content” of the response), ζ, was given by m2/σ2 = 0.31. From the Poisson distribution (Methods), the predicted probability of failure, Po, was Po = e−ζ= 0.74, similar to the observed Po (0.74 in Fig. 3f with apparent failures counted, and 0.85 if uncertain failures also included). This agreement supported the identification of the unitary response. The non-zero peak in the amplitude histograms (Fig. 3g) also roughly matched the σ2/m value. Two other experiments are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. Altogether, seven in situ cells at 35 °C gave similar results: the predicted/observed Po ratio being 0.96 ± 0.17 with apparent failures counted, and 0.79 ± 0.11 with uncertain failures also included, suggesting accurate detection of the unitary response. It was 0.7–2.5 pA (mean±SD = 1.6±0.8 pA) from σ2/m and 0.6–2.8 pA (1.5±0.8 pA) from identified singletons. These values approximated the 1.0–1.3 pA from correcting the mean unitary response (0.3–0.4 pA, see above) at room temperature (23°C) to 35°C by multiplying by 3 (see below and Fig. 4b), supporting the overall quantal analysis. Based on the current-voltage relation for the light response24, a unitary amplitude of ~1.5 pA should decrease by at most ~30 % (to ~1 pA) upon correcting from our holding voltage of −80 mV to the physiological membrane potential (presumably as high as −30 mV, because the ipRGCs showed basal firing; see Supplementary Information S7).

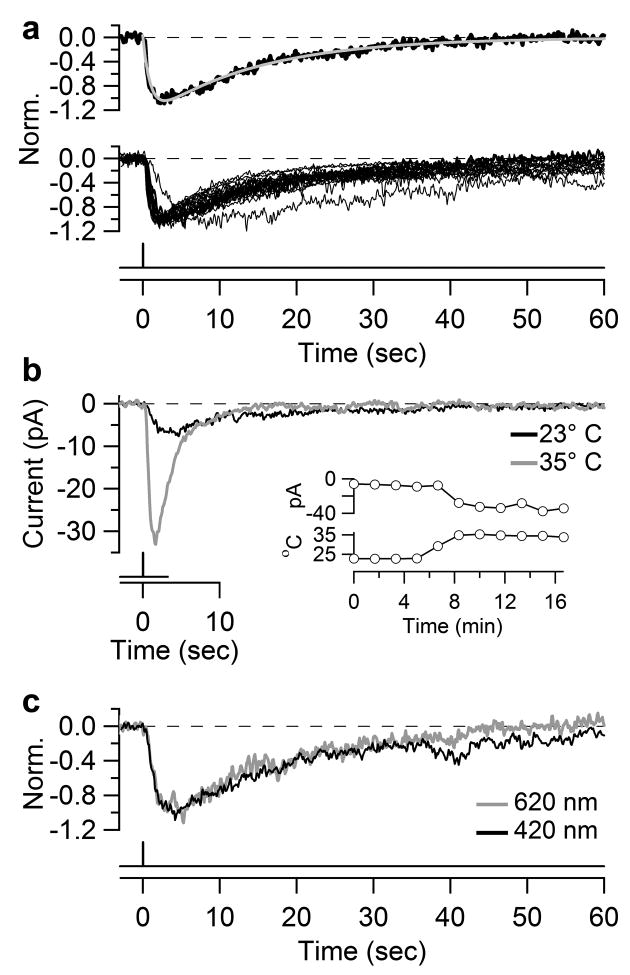

Figure 4.

Kinetics of dim-flash response. a, Top, dim-flash response at 23°C fit with the convolution of two single-exponentials, A(e−t/τ1-e−t/τ2), with A = −1.4 pA, τ1 = 1.0 sec and τ2 = 14.2 sec. Bottom, normalized and superposed dim-flash responses at 23°C from twenty in situ or dissociated ipRGCs used in σ2/m measurements (and with m ≥2 pA for better signal resolution). Dissociated cells: diffuse illumination. In situ cells: 40- or 100-μm spot centered on soma, or 40-μm spot on dendrites. The reason for the unusually slow kinetics of one cell is unknown. b, Dim-flash responses of an in situ ipRGC at 23°C and 35°C. Inset, time course of same experiment showing peak photocurrent above and temperature below. Diffuse illumination. c, Normalized dim-flash responses of an in situ ipRGC stimulated with interleaved 420 nm and 620 nm light. 100-μm spot, 200-msec flash.

A single-photon response of ~1.0 pA (35°C) is larger than that of mouse rods35 and ~100 times that of ground-squirrel cones36. For dissociated cells (consisting largely of soma), the saturated response to bright flashes was 80±70 pA (6 cells) at 23°C. A unitary response of 0.3–0.4 pA at 23°C is thus ~1% of maximum. With a surface area of 520±80 μm2 for 3 dissociated cells (from capacitance measurements), the transduction domain for one photon therefore spans at least ~5 μm2 on the somatic surface. The saturated response of in situ cells to diffuse light was 490±110 pA (3 cells, 23°C), or ~10 times that of dissociated cells and matching the ratio between total and somatic surface areas of rodent ipRGCs (Supplementary Information S6). Thus, phototransduction appears uniform over the entire cell surface.

Kinetics of single-photon response

The single-photon response of ipRGCs was very slow, especially in the decline phase. The response waveform followed the convolution of two single-exponential decays (Fig. 4a, upper panel; time constants of 1.0 sec and 14.1 sec, 23°C), simpler than four stages for the rod response34 or five stages for the cone response36; the quantum bumps of invertebrate photoreceptors are likewise more complex37, 38 (Supplementary Information S8). This kinetics was quite stereotyped (Fig. 4a, lower panel, 20 cells, with average time constants of 1.5 sec (±1.0 sec) and 17.3 sec (±6.8 sec), in situ or dissociated, 23°C). Two time constants does not necessarily mean that phototransduction in ipRGCs has only two steps, but rather that there are two particularly slow steps, the nature of which are unknown. When acutely warmed from 23°C to 35°C, the dim-flash response increased in size by 3.2 ± 1.0 times and in speed by ~3 times (Fig. 4b; time constants of 0.4±0.2 sec and 6.6±4.4 sec at 35°C, 5 cells). The response integration time (ti), a measure of its effective duration and given by ∫f(t)dt/fp, where f(t) is the waveform and fp is its transient peak amplitude39, was 21.7±6.7 sec (20 cells) at 23°C and 7.6±3.5 sec (5 cells) at 35°C. The ti at 35°C was 20 times that of mouse rods32 and >100 times that of rodent cones33, 36.

For a dim flash eliciting few unitary responses, the probability of two photons hitting the same melanopsin molecule is extremely small (Supplementary Information S5), so the kinetics of the dim-flash response (and the single-photon response) should only reflect forward-phototransduction. This property explains the spectral univariance of the dim-flash response amplitude (see earlier) and kinetics (Fig. 4c), as in rods34. The response kinetics was similar for dissociated cells and in situ cells stimulated at the dendrites, suggesting little distortion of these small and slow currents by cell geometry and space-clamp issues (Supplementary Information S1).

Melanopsin density

To estimate membrane pigment density, we asked how many incident photons (Iφ) were required for a unitary response. From the 11 in situ cells giving σ2/m estimates with a 40-μm spot (23°C or 35°C), Iφ= 1.2 × 104–2.7 × 106 (mean±SD = 3.7±7.8 × 105) photons μm−2 (480 nm). Some Iφ value spread might be due to the 40-μm spot (smallest possible aperture) stimulating the variable proximal dendrites (Supplementary Information S6). From 6 dissociated cells with diffuse light (23°C), Iφ= 1.2–5.6 × 105 (3.4±1.5 × 105)photons μm−2. Thus, in situ and dissociated cells both gave Iφ~ 4 ×105 photons μm−2 for the soma. The pigment density, ρm, can be calculated from r2 Iφρm ×3 × 10−8 = 1, or ρm = 108/(3r2 Iφ), where r is somatic radius (Methods). Adopting r~5 μm, we obtained ρm ~3 μm−2, best viewed as an order-of-magnitude estimate (Methods and Supplementary Information S2 and S3). This value is 104-fold lower than the pigment density in rods and cones (~25,000 μm−2; Ref. 40). The melanopsin density on dendrites should be similar (Methods), suggested also by the comparable melanopsin-immunostainings on soma and dendrites3,8,41.

High-efficiency signalling to the brain

To examine the efficiency of signalling by ipRGCs, we recorded spikes from in situ cells in the flat-mount retina (with synaptic blockers present; see earlier) using loose-patch recording for minimal perturbation (Methods; 35 °C). IpRGCs spiked spontaneously in darkness (2.3±2.0 Hz, range 0.2–9.5 Hz, 19 cells; Supplementary Information S7). In Fig. 5, a flash (40-μm spot centred on soma) transiently increased spike rate at intensities of 1.9 × 104 photons μm−2 (480 nm) or higher. From three cells, the threshold was 1.9±3.0 × 105 photons μm−2, producing a transient peak firing rate of 7.7±1.2 Hz. Remarkably, this threshold intensity approximates the ~4 × 105 photons μm−2 required for triggering a single-photon response (previous section), suggesting that ipRGCs can signal single-photon absorption to the brain.

From ipRGC signalling to behavior

We compared the intrinsic sensitivity of a single ipRGC to the behavioural threshold for the melanopsin system, using the pupillary light reflex as a model14,15,42.

We first noted that, with diffuse light, the flash intensity for triggering a single-photon response in an in situ ipRGC should be ~10-fold lower than with somatic stimulation alone, the ratio between in situ cell area to somatic area being ~10 (Supplementary Information S6). Sensitivity also increases 3.5-fold after chromophore application (Supplementary Information S2 and Fig. S5). Thus, for diffuse light under full dark-adaptation, the flash intensity for a single-photon response (hence signalling to the brain) is ~4 × 105/35 = 11,000 photons μm−2. With a continuous step of light (not shown), the corresponding threshold intensity was, after correction, 1,510±1,490 photons μm−2 sec−1 (4 cells), consistent with the 1,375 photons μm−2 sec−1 from dividing the above flash threshold of 11,000 photons μm−2 by the 8-sec integration time. Both values are similar to the ~1,000 photons μm−2 sec−1 measured with multielectrode-array recording from dark-adapted rd/rd mouse retina23 (with all rods and most cones degenerated), which used diffuse light and did not require fluorescence for ipRGC identification.

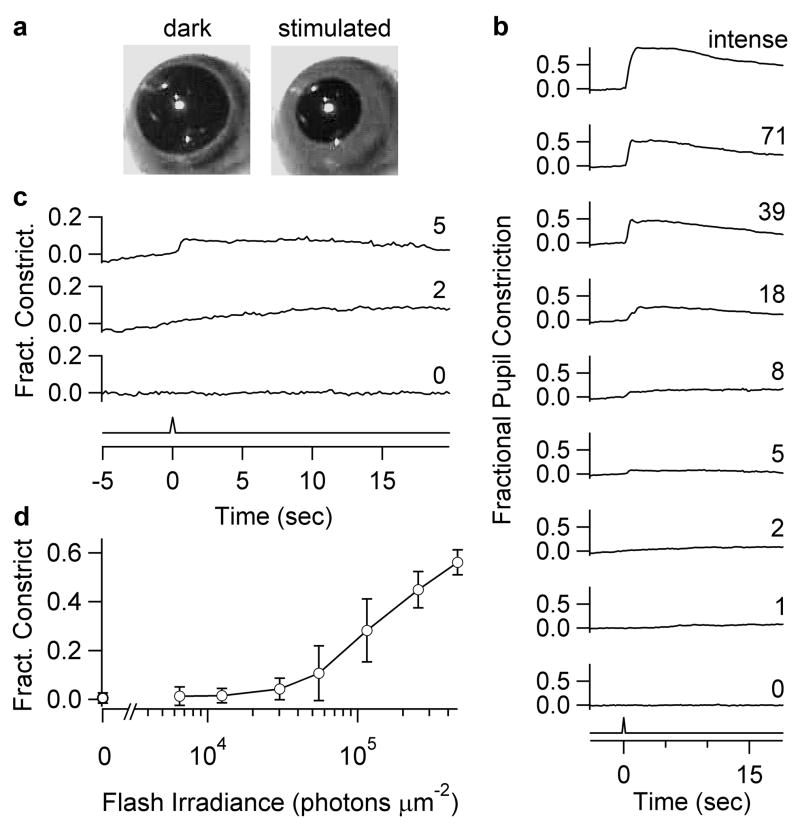

For the consensual pupillary light reflex (Methods and Fig. 6a), we used a gnat1−/−cl mouse43, with non-transducing rods and diphtheria-toxin-ablated cones (a more thorough cone removal than the rd/rd line) to isolate the melanopsin signal. To strictly correlate with single-cell recordings, we stimulated the dark-adapted eye also with 50-msec flashes (Fig. 6b). Pupil constriction was first detectable (~4% of maximal constriction) at a corneal Ganzfeld flash irradiance (480 nm) of 3 × 104 photons μm−2 (6 mice averaged). Dividing this threshold irradiance by the integration time (~8 sec) of the dim-flash response gives a predicted corneal steady irradiance of ~3,750 photons μm−2 sec−1 at reflex threshold, comparable to previous measurements on an analogous mouse line (rd/rd cl; Ref. 14).

Figure 6.

Flash threshold for ipRGC-driven consensual pupillary light reflex. Unanesthetized gnat1−/−cl mice. a, Infrared image of pupil before and after an intermediate-intensity flash. b, Pupil reflex at the relative flash intensities indicated (50-msec; 480-nm except for “intense,” which was white). Ordinate: maximum pupillary constriction within 2 sec after flash, averaged over 800 msec. Traces are averages from 6 mice. Fractional pupil constriction: “0” refers to mean dark pupil area (3.7 mm2) during 1 sec preceding flash, and “1” refers to mean minimal pupil area (0.5 mm2) elicited with a step of white light. c, Reflex measurements on expanded axes for three selected traces in b: no flash (“0”), just below reflex threshold (“2”), and at reflex threshold (“5”), with the last corresponding to a corneal flash irradiance of 30,200 photons μm−2. d, Fractional constriction plotted against corneal flash irradiance. Error bars are S.D.

The corneal flash irradiance of 3 × 104 photons μm−2 corresponds to a diffuse intraocular flash intensity of 7,200 photons μm−2 (Supplementary Information S1). Because 11,000 photons μm−2 were required for a single-photon response (see above), the mean number of single-photon responses per ipRGC at reflex threshold was 7,200/11,000 ~ 0.7. With ~700 ipRGCs per retina3, this threshold corresponds to ~500 single-photon responses over all ipRGCs (or somewhat lower: see Supplementary Information S2). With both eyes stimulated, it would be ~250 per eye because the pupillary light reflex is bilaterally driven44. How many ipRGCs are activated at this reflex threshold? From the Poisson distribution, the probability of one or more single-photon responses in any ipRGC is 1 − P0 = 1−e−0.7 = 0.5, or ~350 cells. Depending on how ipRGC signals are processed at the olivary pretectal nucleus3 and beyond, a few intense-firing ipRGCs may be equally effective.

Conclusions

This work provides a quantitative foundation for understanding ipRGCs, including basic parameters governing their absolute sensitivity. Their single-photon response is even larger than that of rods. The extremely slow response kinetics provides long temporal integration and suits non-image-forming visual functions, where high temporal resolution is non-critical or even undesirable. The density of melanopsin appears to be exceedingly low, with just several molecules per square micron of surface membrane. Compounded by the lack of pigment-containing intracellular membrane stacks41, the photon-capture probability of ipRGCs is more than 106-fold lower than that of rods and cones per unit area of retinal illumination. In principle, the melanopsin density could increase by orders of magnitude without degrading the image on the underlying rods and cones. However, ipRGCs may not need high intrinsic sensitivity. First, rod and cone pathways do drive these cells synaptically at low light levels 22,41,45,46. Second, at least the pupillary light reflex is specifically designed for higher light levels. Even with circadian photoentrainment, it is not obvious that high photosensitivity is an advantage.

Remarkably, a single absorbed photon is sufficient for the spike-generating ipRGC to signal to the brain – as efficient as rods, which signal in analog fashion. The ipRGC achieves this feat by operating near spike threshold in darkness, firing spontaneously at a low rate, such that the small depolarization (~1 mV) caused by one photon can increase spike rate by several-fold. The slow decay of the response also prolongs this effect. Some dissociated ipRGCs fired spontaneously, suggesting that this is an intrinsic property, perhaps expressly for high-efficiency signalling. From the Poisson distribution, the signalling efficiency of ipRGCs at low light intensities is exceedingly sensitive to the threshold number of absorbed photons required for spike modulation. Even a small elevation of this threshold would decrease light signalling efficiency by orders of magnitude (Supplementary Information S9).

As an exemplary non-image-forming visual function at the system level, the pupillary light reflex first appeared with several hundred photoisomerized melanopsin molecules over the entire retina, corresponding to about the same number of activated ipRGCs. This threshold number of active ipRGCs is considerably higher than the several rods and therefore ganglion cells active at the psychophysical threshold of light detection by a dark-adapted human subject47. However, with respect to the pupil reflex, the number of rods and ganglion cells active at threshold in the wild-type mouse is likely very much higher as well (Supplementary Information S10). In other words, the number of required driver cells is task-specific.

Methods Summary

To label ipRGCs, a linearized mouse BAC20 containing tdTomato was injected into B6SJL embryos, with transgenics backcrossed to C57BL/6J. Melanopsin immunostaining3 confirmed specific expression. For recordings, mice (~P20–90) were dark-adapted overnight, anesthetized, enucleated, and euthanized. The retina was flat-mounted or dissociated (Supplementary Information S1). Aerated, heated bicarbonate-buffered Ames, containing synaptic blockers for flat-mount experiments, ran at ~5 ml/min through a 1-ml chamber. IpRGCs were visualized with seconds of fluorescence followed by infrared-DIC (Supplementary Information S1). Patch-clamp recordings used a KCl-based pipette solution (pH 7.2; see continued Methods) supplemented with (in mM) 2 glutathione, 4 MgATP, and 0.3 Tris-GTP for whole-cell recordings or, alternatively, 125–250 μM amphotericin B for perforated-patch recording. For loose-patch recordings, the pipette contained HEPES-buffered Ames. Pipettes were parafilm-wrapped, and an Axopatch 200B in voltage-clamp or fast-current-clamp utilized (Supplementary Information S1). Recording stability was checked periodically with a test flash, and series resistance monitored. Vhold was −80 mV, initially for improving signal resolution though the photocurrent I–V relation was later shown to be rather shallow between −90 mV and −30 mV (Ref. 24). Liquid-junction potential was corrected. Photocurrent was low-pass filtered at 2 Hz (dim flashes) or 10 Hz (bright flashes) and membrane voltage at 10 kHz. Loose-patch recording bandwidth was 10 Hz - 1 kHz, sometimes with a notch filter. Sampling exceeded the Nyquist minimum. Flashes (10-nm bandwidth or occasionally white) were diffuse (730-μm diameter spot) or local (40-or 100-μm diameter), temporally spaced for full recovery between flashes (30–120 sec). White flashes, for response saturation, were converted to equivalent 480-nm flashes by response-matching (Supplementary Information S1). Consensual pupillary light reflex measurements followed previous work14, with one eye of the unanesthetized mouse videoed under infrared and the other stimulated by Ganzfeld light (Supplementary Information S1). Data are mean ± S.D.

Methods

Solutions

For whole-cell and perforated-patch recordings, the unsupplemented pipette solution was (in mM) 110 KCl, 13 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.2 with KOH. For loose-patch recordings, it was an “ionic Ames” containing (in mM) 140 NaCl, 3.1 KCl, 0.5 KH2PO4, 1.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 6 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 with NaOH. Fast synaptic transmission was blocked by adding to the bath 50 μM D,L-APV, 20 μM CNQX, 100 μM hexamethonium bromide, 100 μM picrotoxin, and 1 μM strychnine. 3 mM kynurenate sometimes replaced the first three. On rare occasions, some synaptic transmission persisted in this cocktail (evidenced by a short-latency, transient light response preceding the intrinsic light response), and was abolished by adding 100 μM L-AP4.

Fluctuation/quantal analyses

These were as described for retinal rods34. At 23°C, the single-photon response was not individually resolvable, but estimated from the ensemble variance-to-mean ratio, σ2/m, at the peak of the mean response, m(t), to dim flashes. The quantal content of m(t), ζ, is given by ζ = m/(σ2/m) = m2/σ2. The predicted Poisson distribution for comparison with the amplitude histogram was calculated from Pn =ζne−ζ/n!, where n = 0, 1, 2, etc., and Pn is the probability of n unitary responses in any trial. NPn was then plotted against n(σ2/m), where N is the total number of stimulus trials. At 35°C, the single-photon response was just resolvable, as were the failures, so σ2/m could be directly compared to the singletons. The method to identify the singletons is described in Supplementary Information S1.

Melanopsin-density calculations

Melanopsin is supposed to be situated only on the plasma membrane41. The Beer-Lambert Law states that OD = log10(Ii/It) = εCL, where OD is optical density, Ii and It are incident and transmitted intensities, ε is the molar extinction coefficient, C is molar concentration, and L is path length48. For dilute pigment, this equation approximates to Ia/Ii = 2.3εCL. Suppose R is the total number of pigment molecules in a planar membrane of volume V (liters), then C = R/(6 × 1023× V) mole liter−1. L (μm) is given by (V × 1015)/A, where A is membrane surface area (μm2). Thus, for incident light normal to the planar membrane, Ia/Ii = 3.83× 10−9×ε× ρm, where ρm = R/A is the pigment density on membrane. Taking into account the quantum efficiency of isomerization, Qisom, and assuming that every isomerized pigment molecule triggers an electrical response (as in rods, cones and invertebrate photoreceptors; see Supplementary Information S3), the number of single-photon responses triggered by Ii is given by 3.83 × 10−9×ε× ρm× Qisom× IiA.

For rhodopsin (randomly oriented) in solution, ε ~ 42,000 M−1 cm−1 for photons at λmax (Ref. 49). For a planar membrane, the chromophore (11-cis-retinal) of all pigment molecules is oriented roughly parallel to the membrane surface, so that for unpolarized light at normal incidence, the probability of absorption is 50% higher than in solution50, giving an ε of ~63,000 M−1 cm−1, or 6.3 mole−1 liter μm−1 at λmax. This parameter is unlikely to be very different between rhodopsin and melanopsin at their respective λmax’s (Supplementary Information S3), because it depends mostly on the chromophore, and melanopsin uses also 11-cis-retinal16. For the same reason, Qisom should be similar between rhodopsin (0.67; see Ref. 50) and melanopsin, and, indeed, across a wide variety of pigments (Supplementary Information S3). To apply the calculations to ipRGCs, we need to consider two more factors. First, for a spherical membrane (as of a cell soma), the average probability of absorption for roughly collimated light is lower by a factor of 2 compared to planar membrane (Supplementary Information S4). Second, there was a 3.5-fold increase in ipRGC sensitivity with 9-cis-retinal incubation, suggesting that some pigment was without chromophore, or bleached, at the beginning of recording (although the true correction factor may be somewhat less than 3.5; see Supplementary Information S2). Substituting all of the above parameters into the final expression in the previous paragraph, and with A = 4πr2, where r (in μm) is the somatic radius, we arrive at the number of single-photon responses produced by a flash of intensity Ii (photons μm−2) at λmax (480 nm) on the ipRGC soma as being 3.83 × 10−9× 6.3 × ρm× 0.67 × Ii× 4 πr2 = 3 × 10−8× r2 Ii ρm. From the measured Ii for triggering one single-photon response (Iφ, see text in paper), ρm can be evaluated. If not every isomerized melanopsin molecule triggers an electrical response, the estimated melanopsin density should scale up proportionally. We consider the above calculations as an order-of-magnitude estimate.

The melanopsin density on the dendrites is unlikely to be very different from that on the soma, as can be seen from the following. The Michaelis equation (the exact relation is in fact non-critical, as long as linearity holds at low flash intensities) describing the intensity-response relation is:

where Rmax is the saturated response. For small I, this becomes R = Rmax(I/I1/2). Suppose, for local illumination on soma, Rφ,s is the single-photon-response amplitude elicited by Iφ,s photons μm−2 on soma, and I1/2,s and Rmax,s are the half-saturating flash intensity and the saturated response on the soma, respectively; likewise, suppose Rφ,d, Iφ,d, I1/2,d, and Rmax,d have the same meanings for dendritic illumination. Thus,

Combining these two equations, and because we found (see text in paper) Rφ,s ~ Rφ,d, I1/2,s ~ I1/2,d, and Rmax,s/Rmax,d ~ As/Ad, where As and Ad are the somatic and dendritic light-collecting areas, we have

Thus, roughly the same overall number of photons is required for producing the single-photon response on the somatic surface as on the dendrites. The parsimonious interpretation is a similar melanopsin density in both locations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by an NRSA fellowship and a VNTP Training Grant to M.T.H.D., and NIH grants to K.-W.Y. and D.E.B. We thank Yiannis Koutalos, Vikas Bhandawat, Dong-Gen Luo, Vladimir Kefalov, Dan Liu, Gaby Maimon, and Chih-Ying Su for valuable discussions, and Yaping Wang, Justin Hsieh, and Naoko Nishiyama for technical assistance. We also thank Jeremy Nathans and Roger Reeves for suggestions on transgenic lines, Jeremy Nathans and Hugh Cahill for the gnat1−/− cl mouse line, and Terry Shelley for expert machining. We dedicate this work to the Champalimaud Foundation, Portugal.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

M.T.H.D. and K.-W.Y. designed the experiments and wrote the paper. All experiments were performed by M.T.H.D., except for pupil measurements, which were done by T.X. and M.T.H.D. The melanopsin-tdTomato BAC-transgenic mouse was generated by S.H.K. in the laboratory of D.E.B. Important early observations of the intensity-response relation and kinetics were made by H.Z. using animals retrograde-labelled by H.-W.L.

Competing Interests Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Hankins MW, Peirson SN, Foster RG. Melanopsin: an exciting photopigment. Trends Neurosci. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berson DM, Dunn FA, Takao M. Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science. 2002;295:1070–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1067262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hattar S, Liao HW, Takao M, Berson DM, Yau KW. Melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells: architecture, projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science. 2002;295:1065–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1069609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guler AD, et al. Melanopsin cells are the principal conduits for rod-cone input to non-image-forming vision. Nature. 2008;453:102–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatori M, et al. Inducible ablation of melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion cells reveals their central role in non-image forming visual responses. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hattar S, et al. Melanopsin and rod-cone photoreceptive systems account for all major accessory visual functions in mice. Nature. 2003;424:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nature01761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Provencio I, Jiang G, De Grip WJ, Hayes WP, Rollag MD. Melanopsin: An opsin in melanophores, brain, and eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:340–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Provencio I, Rollag MD, Castrucci AM. Photoreceptive net in the mammalian retina. This mesh of cells may explain how some blind mice can still tell day from night. Nature. 2002;415:493. doi: 10.1038/415493a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melyan Z, Tarttelin EE, Bellingham J, Lucas RJ, Hankins MW. Addition of human melanopsin renders mammalian cells photoresponsive. Nature. 2005;433:741–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu X, et al. Induction of photosensitivity by heterologous expression of melanopsin. Nature. 2005;433:745–9. doi: 10.1038/nature03345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panda S, et al. Illumination of the melanopsin signaling pathway. Science. 2005;307:600–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1105121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu Y, et al. Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells detect light with a vitamin A-based photopigment, melanopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10339–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501866102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gooley JJ, Lu J, Chou TC, Scammell TE, Saper CB. Melanopsin in cells of origin of the retinohypothalamic tract. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1165. doi: 10.1038/nn768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucas RJ, et al. Diminished pupillary light reflex at high irradiances in melanopsin-knockout mice. Science. 2003;299:245–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1077293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panda S, et al. Melanopsin is required for non-image-forming photic responses in blind mice. Science. 2003;301:525–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1086179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker MT, Brown RL, Cronin TW, Robinson PR. Photochemistry of retinal chromophore in mouse melanopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8861–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711397105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu X, Berson DM. Melanopsin Bistability in Ganglion-Cell Photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48 E-Abstract 612. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koyanagi M, Kubokawa K, Tsukamoto H, Shichida Y, Terakita A. Cephalochordate melanopsin: evolutionary linkage between invertebrate visual cells and vertebrate photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1065–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mure LS, Rieux C, Hattar S, Cooper HM. Melanopsin-dependent nonvisual responses: evidence for photopigment bistability in vivo. J Biol Rhythms. 2007;22:411–24. doi: 10.1177/0748730407306043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang XW, Model P, Heintz N. Homologous recombination based modification in Escherichia coli and germline transmission in transgenic mice of a bacterial artificial chromosome. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:859–65. doi: 10.1038/nbt0997-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaner NC, et al. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1567–72. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dacey DM, et al. Melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells in primate retina signal colour and irradiance and project to the LGN. Nature. 2005;433:749–54. doi: 10.1038/nature03387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tu DC, et al. Physiologic diversity and development of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2005;48:987–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warren EJ, Allen CN, Brown RL, Robinson DW. Intrinsic light responses of retinal ganglion cells projecting to the circadian system. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1727–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt TM, Taniguchi K, Kofuji P. Intrinsic and extrinsic light responses in melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells during mouse development. J Neurophysiol. 2008 doi: 10.1152/jn.00062.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baylor DA, Hodgkin AL, Lamb TD. The electrical response of turtle cones to flashes and steps of light. J Physiol. 1974;242:685–727. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baylor DA, Lamb TD, Yau KW. The membrane current of single rod outer segments. J Physiol. 1979;288:589–611. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo D-G, Kefalov V, Yau K-W. In: The Senses: A Comprehensive Reference. Basbaum AI, editor. Elsevier/Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong KY, Dunn FA, Berson DM. Photoreceptor adaptation in intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2005;48:1001–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamb TD, McNaughton PA, Yau KW. Spatial spread of activation and background desensitization in toad rod outer segments. J Physiol. 1981;319:463–96. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong KY, Ecker JL, Dumitrescu ON, Berson DM, Hattar S. Multiple Morphological Types of Melanopsin Ganglion Cells with Distinct Light Responses and Axonal Targets. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49 E-Abstract 1518. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raport CJ, et al. Downregulation of cGMP phosphodiesterase induced by expression of GTPase-deficient cone transducin in mouse rod photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:2932–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikonov SS, Kholodenko R, Lem J, Pugh EN., Jr Physiological features of the S- and M-cone photoreceptors of wild-type mice from single-cell recordings. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:359–74. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baylor DA, Lamb TD, Yau KW. Responses of retinal rods to single photons. J Physiol. 1979;288:613–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CK, et al. Abnormal photoresponses and light-induced apoptosis in rods lacking rhodopsin kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3718–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kraft TW. Photocurrents of cone photoreceptors of the golden-mantled ground squirrel. J Physiol. 1988;404:199–213. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardie RC, Postma M. In: The Senses: A Comprehensive Reference. Basbaum AI, editor. Elsevier Science/Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dorlochter M, Stieve H. The Limulus ventral photoreceptor: light response and the role of calcium in a classic preparation. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;53:451–515. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baylor DA, Hodgkin AL. Detection and resolution of visual stimuli by turtle photoreceptors. J Physiol. 1973;234:163–98. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liebman PA, Parker KR, Dratz EA. The molecular mechanism of visual excitation and its relation to the structure and composition of the rod outer segment. Annu Rev Physiol. 1987;49:765–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.004001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belenky MA, Smeraski CA, Provencio I, Sollars PJ, Pickard GE. Melanopsin retinal ganglion cells receive bipolar and amacrine cell synapses. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:380–93. doi: 10.1002/cne.10652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lucas RJ, Douglas RH, Foster RG. Characterization of an ocular photopigment capable of driving pupillary constriction in mice. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:621–6. doi: 10.1038/88443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cahill H, Nathans J. The optokinetic reflex as a tool for quantitative analyses of nervous system function in mice: application to genetic and drug-induced variation. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grozdanic S, et al. Characterization of the pupil light reflex, electroretinogram and tonometric parameters in healthy mouse eyes. Curr Eye Res. 2003;26:371–8. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.26.5.371.15439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong KY, Dunn FA, Graham DM, Berson DM. Synaptic influences on rat ganglion-cell photoreceptors. J Physiol. 2007;582:279–96. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perez-Leon JA, Warren EJ, Allen CN, Robinson DW, Lane Brown R. Synaptic inputs to retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1117–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04999.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hecht S, Shlaer S, Pirenne MH. Energy, Quanta, and Vision. J Gen Physiol. 1942;25:819–840. doi: 10.1085/jgp.25.6.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lisman JE, Bering H. Electrophysiological measurement of the number of rhodopsin molecules in single Limulus photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol. 1977;70:621–33. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.5.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harosi FI. Absorption spectra and linear dichroism of some amphibian photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol. 1975;66:357–82. doi: 10.1085/jgp.66.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dartnall HJA. In: Photochemistry of Vision. Dartnall HJA, editor. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1972. pp. 122–145. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.