Abstract

Smoking rates among military personnel are high, damaging health, decreasing short- and long-term troop readiness, and costing the Department of Defense (DOD). The military is an important market for the tobacco industry, which long targeted the military with cigarette promotions. Internal tobacco industry documents were examined to explore tobacco sponsorship of events targeted to military personnel. Evidence was found of more than 1,400 events held between 1980 and 1997. In 1986, the DOD issued a directive forbidding such special promotions; however, with the frequently eager cooperation of military personnel, they continued for more than a decade, apparently ceasing only because of the restrictions of the Master Settlement Agreement. The U.S. military collaborated with the tobacco industry for decades, creating a military culture of smoking. Reversing that process will require strong policy establishing tobacco use as unmilitary.

INTRODUCTION

The 1.3 million active duty personnel in the U.S. military1 are a desirable market for tobacco companies:2 people near the typical age of smoking uptake,3 entering an institution with high smoking prevalence (32.2% in 2005).1 Military recruits skew toward some of the tobacco industry’s prime targets: young adults, high school educated, and African-American.4–7 Smoking diminishes even short-term troop health and readiness8,9 and increases medical and training costs.10–12

Goods, such as cigarettes, may be promoted through sponsorship of events. Sponsorship creates a public presence for the product;13 advertising for the event becomes advertising for the sponsor as well.14 Sponsorship builds on loyalties and associations customers already have.14 Sponsorship can be more powerful than advertising, as it is more covert, and does not trigger the skepticism recognized advertising invokes.14 Consumers will even pay to participate in sponsored events, although the events communicate commercial messages they otherwise avoid.15 When the sponsor is perceived as having made a desired event possible, the consumer may see the brand as a benefactor.16 This study examines tobacco industry use of sponsorship to promote cigarettes to active duty military.

BACKGROUND

Tobacco use has long been associated with military service; until 1975, tobacco was included in basic field rations.17 The Department of Defense (DOD) sells tobacco products through commissaries and exchanges, stores located on military bases. Before the mid-1990s, tobacco products sold in these stores were deeply discounted;18 prices have been raised to within 5% of the local retail price,19 but, as for all items in the stores, no state or local taxes are applied.

Profits from tobacco products help fund Morale, Welfare, and Recreation (MWR) programs.20 MWR is responsible for promoting the physical, mental, and social well-being of military members and their families through programs such as sports, child development, and youth programs.21 Commanders also support these programs out of their Operations and Maintenance budgets; however, no specific amounts are earmarked for MWR programs, which must compete with operational requirements for funds.22 The exchanges, the MWR program bureaucracy, and base commanders may thus be motivated to continue sales of tobacco products.

Directive 1010.10

In 1986, Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger released Health Promotion Directive 1010.10.23 In addition to declaring many areas nonsmoking and mandating cessation and prevention programs, the directive forbade participation “with manufacturers or distributors of … tobacco products in promotional programs, activities, or contests aimed primarily at DOD personnel.”23 The directive specified that support from alcohol or tobacco companies “for worthwhile programs” was acceptable as long as there was no advertising “directly or indirectly identifying [a] … tobacco product.”23

METHODS

Some 10 million tobacco industry internal documents have been made public through state attorneys general litigation. 24 We searched the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library(http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/index.html) and http://tobaccodocuments.org using a snowball strategy,25 beginning with keywords (e.g., “military AND sponsorship”). Additionally, we searched news stories on the Lexis-Nexis and News Bank databases. Documents were deemed relevant if they mentioned military tobacco sponsorships.

Data from approximately 1,200 documents, including correspondence, contracts, marketing research, and reports, dated 1981–2001, were analyzed using an interpretive approach. 26–29 All documents were reviewed by the first author, and both authors reviewed selected key documents and took detailed notes. We used iterative reviews of documents, notes, and secondary source materials to develop an historical case study. 29,30

This study has limitations. The document set is not comprehensive, but a selection of litigation-related material. As no tobacco litigation to date concerns the military, there may be unavailable documents that contain additional information. We also may not have identified all relevant available documents because of their volume. Military records were not readily available; thus, descriptions of the military perspective are limited.

RESULTS

Tobacco industry contracts with MWR offices show two kinds of sponsorship. For large events, such as concerts, tobacco companies paid for production (e.g., performers’ fees) in exchange for the right to promote the event and their product. MWR offices retained money from tickets and concessions. For smaller events, such as bowling tournaments or bar nights, tobacco companies paid fees (under $5,000) to “brand” the event. In addition, companies supplied branded items such as prizes, napkins, and T-shirts.31–33 Between 1981 and 2000, tobacco companies sponsored more than 1,450 events for military personnel (Table I). Most of these events were held on military bases; 217 were held at off-base bars and clubs that catered to military personnel. Services targeted and event location details are summarized in Tables II and III. All figures are minimums; the total number of events is unknown, as the document collections are not complete. Philip Morris (PM) noted that in both 1994 and 1995 the company sponsored over 35,000 events that were not included on their own event calendars;34 whether or how many of these were on military bases is unknown.

TABLE I.

Event Type

| Event Type | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Contest/Game* (e.g., Darts, Bingo) | 576 | 39.6 |

| Concert | 344 | 23.6 |

| Bar Night | 134 | 9.2 |

| Participatory Sport (e.g., Softball, Golf) | 116 | 8.0 |

| Sampling | 80 | 5.5 |

| Spectator Sport (e.g., Auto Racing, Airshow) | 78 | 5.4 |

| Outdoor Event (e.g., Fair, Picnic) | 49 | 3.4 |

| Other Performance | 10 | 0.7 |

| Other | 69 | 4.7 |

| Total | 1456 | 100.0 |

Note: Contests and games were frequently held in bars; items were counted under “bar night” if no special activities were mentioned.

TABLE II.

Events by Military Service Targeted

| Service | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Army | 308 | 21.2 |

| Navy | 216 | 14.8 |

| Marines | 96 | 6.6 |

| Air Force | 98 | 6.7 |

| Other | 5 | 0.4 |

| No Data | 733 | 50.3 |

| Total | 1456 | 100.0 |

Documents frequently tabulated numbers of events without specifying locations.

TABLE III.

Events by Geographic Location

| Location | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| U.S./Territories | 138 | 92.6 |

| Europe | 89 | 6.1 |

| Asia | 13 | 0.9 |

| Mideast | 3 | 0.2 |

| Other | 3 | 0.2 |

| Total | 1,456 | 100.0 |

Promotional Events, 1980–1986

Kool Super Nights

Sponsorship of large events on military bases began in 1981, when Brown & Williamson (B&W) expanded its Kool Jazz festivals onto military bases. According to a B&W overview of the program’s first year, the military was “virtually an untouched market for this type of activity.”35 Neither B&W nor the military knew how to proceed, since it was “a totally new concept.”35 However, B&W learned to get approval for their Kool Super Nights (KSN) concerts through the Morale and Welfare Support Office (later MWR).35

There were 132 KSN events over 5 years. In 1983 more than 40 concerts were held, including on bases in West Germany and an aircraft carrier.36 In 1984 the overseas component covered more West German bases13 and others in Panama,37 Guam,38 and Okinawa.39 Overseas, tobacco company promoters noted, “your audience is even more isolated,”40 making it more dependent on on-base events.

B&W personnel noted that KSN concerts could be exploited through “special promotional programs” for stores and clubs on base, and “incentive items that are personalized to tie in Kool with the individual base.”35,41 Marketing managers were told to “develop a three- to five-week promotional program” for each show.42 On some bases, local bands competed to be the opening act for the concert. 40 B&W distributed branded premiums such as “keychains, cards, and notebooks” 43 with purchases of Kools in base stores, and sponsored events at the base clubs featuring “Kool napkins and Kool ash trays” as well as prizes such as “T-Shirts, caps, and radios.”31 Branded items, B&W hoped, would “be around long after each concert and thus serve as a reminder of Kool’s sponsorship.”31 These activities helped the company “aggressively saturat[e] each military base.”31

Belair Bingo

Military wives were targeted through a B&W Belair Bingo promotion, starting in 1982. The brand provided bingo cards and chips, and prizes including lighters, T-shirts, and gift certificates. Participants received cigarettes, coupons, matches, romance novels,44 and catalogs for more branded items.45 The brand manager suggested that account managers approach MWR offices that sponsored bingo nights, and that already had a relationship with B&W through the KSN program.46 However, in both cases he emphasized that they were “not sponsoring the bingo events … Rather, we are donating specific items intended to supplement a base function.”44,46

Newport Face-to-Face Marketing

According to a Lorillard brand planning document, “there isn’t a market in the country that has the sales potential for Newport like the military market,” adding that “the plums are here to be plucked.”47 Furthermore, the “face-to-face” promotions they were planning were new:47,48 the “Newport Military Challenge” organized activities such as tug-of-wars, and milk chugging, one-armed pushup, and dance contests at fairs and picnics.49,50

The advantage of such programs over large event sponsorship, according to the brand manager, was that large events didn’t “involve” participants,51 while base fairs allowed Newport “to become PART of an already-established event” that was “ENDORSED by the military” (emphasis in original). Thus, “enlistees had a pre-disposition to become involved in Newport activities.”52 Brand exposure was good; at the Fort Bragg fair the “Newport camp” was at the “the only entrance/exit to the fair,” so that attendees “could not miss the Newport stage” and the “Alive with Pleasure” banners “strung in all the trees in the immediate area.”48

Company personnel distributed cigarettes at these events (100,000 sample packs at 5 bases in 1983)53 as well as premiums. A beach fair at the San Diego Naval Training Center resulted in “young Marines everywhere wearing ‘Alive with Pleasure’ Newport T-shirts and baseball caps.”54 Another Newport program parked a van on base—frequently in front of the base store—to distribute free cigarettes or coupons.55–57 In 1985, DOD apparently forbade sampling (i.e., giving out free cigarettes) on military bases;40 after this time, tobacco companies handed out coupons.

Merchandising Policy Implementation

Response to the 1986 Directive 1010.10, disallowing most tobacco sponsorship,23 was mixed. The Director of Commissary Operations for the Army and the Air Force Commissary Commander issued directives restricting promotional activity in stores.58–60 A legal memo to R. J. Reynolds (RJR) noted that the commissary directors had formulated these regulations voluntarily, to avoid stricter regulation from the DOD;61 the Army Commissary Director asserted that the regulations would “ensure that, in the future, we will be able to sell cigarettes.”58 However, tobacco companies were concerned that Directive 1010.10—particularly its restrictions on smoking—was causing a decline in sales;62–64 because sales had been declining before the directive was issued and restrictions were introduced gradually, the evidence was inconclusive.65,66

Promotional Events, 1988–2000

Marlboro Music Military Tour

The sponsorship restrictions were eased in February 1988. Although soliciting sponsorship from tobacco companies was still prohibited, it could be accepted if offered, and if “the company sponsors similar events in civilian communities.”67 PM became aware of this change in July,68,69 and sponsored a series of concerts at bases in Germany.70 In October 1988, Marlboro supplied country music bands for grand reopening celebrations at seven Air Force commissaries. In 1989 Philip Morris began the Marlboro Music Military (MMM) tour, which presented 151 concerts through 1997. The MMM tour was designed to target young adult men,71 as well as to generate “positive publicity to counteract the anti-smoking message”72 promulgated by the military.

The events had particular value, PM thought, because of the target audience’s situation; MMM events were often “the only professional concert entertainment in military communities.”73 In addition, the sponsorship money, concession profits74 (and ticket receipts, if any) allowed MWR to “fund … their year long activities,”73 thus earning gratitude from MWR and command personnel. For example, a 4-day Marlboro-sponsored Independence Day event on a Navy base in Spain included concerts, a golf tournament, fireworks, product sampling, and a “Marlboro Country Store” that sold over 10,000 branded items.75 Marlboro had “enthusiastic support and goodwill on the base at every command level.”75 A PM employee reported that, “On the last evening of activities several thousand people were standing with tears in their eyes singing ‘Proud to be and [sic] American.’ They couldn’t thank Marlboro enough.”75 Overall, PM concluded that MMM gave them “a great return on our investment.”76

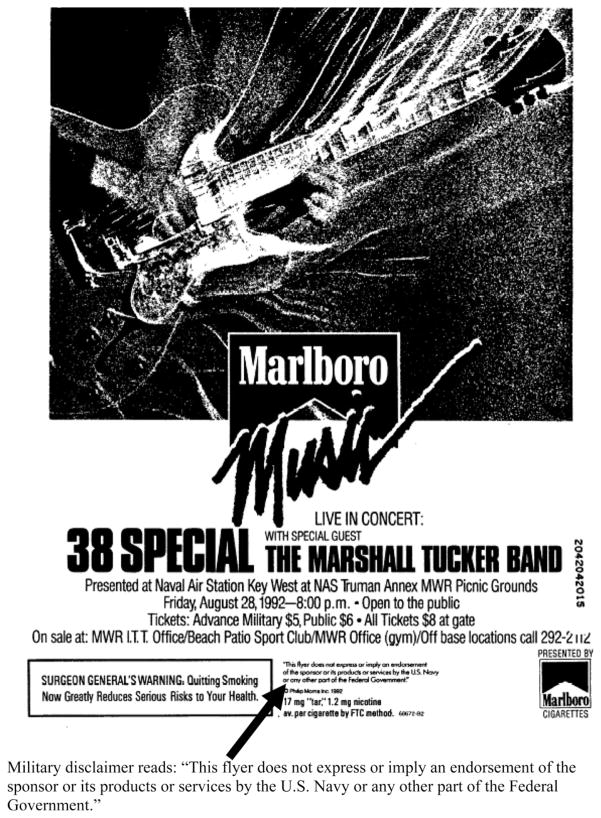

Like KSN concerts, MMM events were promoted on bases for weeks.77–79 From at least 1984, advertising material was required to have a disclaimer of military or government endorsement (see Figure 1),36,80 which appeared in type approximately half the size of the mandated government health warning. The disclaimer was made weaker by the mention of the military location and ticket sales conducted by the base MWR office. In at least one case, PM was advised that the Army insisted that the “base name must preceed [sic] Marlboro Music,” so posters read, “Fort Polk Welcomes Marlboro Music.”80

FIGURE 1.

Event promotion materials with military disclaimer.

When queried by a reporter about the conflict between the sponsored concerts and DOD policy, PM replied that “the concerts offer no free give away items, there is no promotion of the product other than the sign for the concert with the name Marlboro on it, and there is no ‘pushing’ of the product.”81 It is possible that this was true at the concert in question; however, planning documents for another concert that same year specified: “Marlboro Music flags placed on main road leading to the festival entrance; Marlboro pennants to be placed throughout venue…; light boxes with Marlboro music logo placed in strategic locations; banners … to enhance overall Marlboro visibility; van/truck participation … for on-site and bar night coverage; two… tents, six kiosks, and four pick-up trucks for on-site name generation and pack sale activities; … T-shirts, … caps, lighters, fanny packs, cassette holders, stadium seats, [and] additional incentives.”82

Other PM Activities

In 199083 and 199484 Marlboro Grand Prix auto races were heavily promoted at military bases in California,84 Arizona,83 Oregon,83 Ohio,83 Virginia,85 Colorado,86 and South Carolina.85 In 1994 these promotions included agreements with Camp Pendleton and MCAS El Toro for Marlboro bar nights, Marlboro banners throughout the bases, and product sales at the base stores.87 Marlboro paid each base $1,000, and donated 2,000 Grand Prix time trial tickets, 60 tickets to the race, and branded premium items.87

Like Newport, Marlboro used branded vans to distribute samples or coupons. This program lasted through the late 1990s;88,89 however, no details as to number or location of events could be found. In 1994 and 1995, the Marlboro van was involved in over 36,000 events; it is unknown how many of these were directed toward military audiences.34

Exchange Initiative Program

RJR’s “Exchange Initiative Program” (EIP)90 held events at locations on base, such as noncommissioned officer and enlisted clubs, and at bars and nightclubs near bases that catered to young military personnel.91 We identified nearly 200 events held on base during the EIP’s 2 years, 1990–1991, and 124 off base. On-base EIP events included concerts, air shows, bowling nights, Superbowl parties, golf tournaments, Halloween parties, and beach picnics, among others.

Many events featured the “Smooth Character,” (a.k.a. Joe Camel), accompanied by women called “Joe’s Squad.”92 Joe’s Squad gave smokers “the opportunity to converse and partake in entertaining activities with these women; and creat[ed] exciting atmosphere and visibility,” while promoting Camel.92 The Squad conducted games at bar nights, signed autographs, and had their pictures taken “with key VIP’s and military personnel.”93 An RJR-created musical group called “Smooth Moves,” consisting of “four beautiful and talented singers plus a Rock and Roll MC,” also performed at these venues.94

Military Cooperation and Resistance

MWR Personnel

The Morale, Welfare, and Recreation officers who arranged the events were, according to PM, frequently grateful95–97 and “enthusiastic partners … responsive to our every request.”98 MWR directors provided contacts with “athletic directors and on-base club managers,” and assisted in “obtaining [commanding officer] approval.”99 Contracts for large scale events such as concerts specified that the MWR office would supply considerable logistic support (see Table IV).

TABLE IV.

Typical Contractual Responsibilities of Military Organization in Exchange for Major Event Sponsorship

|

MWR units frequently went beyond the terms of their contract,100 acting energetically on behalf of the companies. B&W reported that MWR offices eagerly promoted KSN concerts, initiating activities such as handing out fliers, putting announcements on the base radio station and in the base newspaper, creating signs for on-base high-traffic locations, “announcing the show via sound trucks routed through housing areas[, and] busing basic trainees to the shows.”35

In 1991 the MWR representative described Pearl Harbor Navy Exchange activities to “move product” for RJR at the Top Gun Hydrofest.101 These included special placement of Winston in the stores, a “massive promotion campaign offering” $3 cartons of Winston, selling Winston T-shirts and caps, displaying the Winston Eagle hydroplane at the Aloha Family Festival, and placing the “Winston name and logo … on the only electronic display sign in Hawaii … at the key intersection on the Naval installation,” which showed it “a minimum of 100 times per day for a 30-day period.”101

This MWR representative was equally enthusiastic about the “Smokin’ Joe” (Camel) Hydroplane in 1995. His goal was “to make the pit area look and feel like a Smokin’ Joe’s pit with signs, banners, flags, and anything else.”102 He planned to create a 16 × 16 foot mural and requested “costumed characters … flags or pennants … The bigger the better.”102 He also wanted “Smokin’ Joe’s pens, key chains etc.,” to give to the guests at the Kick Off Breakfast at the Hawaii governor’s home, and to use as prizes at the associated golf tournament.102

The typical sponsorship contract between the MWR office and the tobacco company specified MWR’s objective as promoting a “healthy lifestyle … for soldiers and their families.”103,104 The contradiction between promoting tobacco and promoting healthy lifestyles was not acknowledged.

Military Store Personnel

Sponsorship was used to improve relationships with commissary and exchange managers.43 Tobacco companies and brands competed for limited shelf space at military stores; good relationships could increase orders.35,76 For instance, PM believed that MMM had created “a number of close working relationships with” military store managers76 and that “as a result, all brands now have merchandising participation and shelf space which they would not normally have.”105

Command Personnel

All events had to be approved by base commanders.106,107 In addition, high-ranking military personnel frequently attended98,108,109 or participated in tobacco-sponsored events.110 For instance, Marlboro-sponsored golf and bowling tournaments at Guantanamo Bay in 1991 featured a raffle of a “Marlboro golf bag and a bowling ball and bag … with the proceeds going to the base Navy Relief Fund,” a favorite charity of the base commander.111

PM noted that the Marlboro concerts helped the company “develop a close working relationship with the base commander … the most important contact we can make.”76 The commander could get “compliance from all parties.”76 The base commander could also solve problems. At Fort Bliss in 1995 there was discontent over the lack of acts on the Marlboro concert bill that appealed to African-American personnel. A PM report noted that the “base commandant … did an excellent job of handling the situation and from that day forward, was present at every interview …. The question … disappeared.”98

Resistance

Some commanders attempted to restrict tobacco company activity. In the first year of KSN concerts, Fort Sill required B&W to use coupons rather than samples.112 When Barksdale AFB objected to sampling, the Kool brand manager said the concert would be held elsewhere.113 Evidently, this threat worked, as there were no restrictions at Barksdale; in addition, a later report mentioned that Fort Sill personnel “advised that approval for sampling could now be obtained.”35 Lorillard also ran into resistance to its van program.114,115 One Lorillard employee reported that all military bases in the Washington, DC area, except Fort McNair, had rejected sampling, and Fort McNair withdrew approval after base medical personnel objected.116

In 1986, Fort Benning demanded that KSN comply with regulations forbidding tobacco product advertisement.117 In response, B&W cancelled the concert.118 No other bases made this demand. In May 1988—2 months after the sponsorship rules were eased—the commander of the Navy base in Guantanamo Bay reaffirmed that events could only be sponsored by tobacco or alcohol companies if the product name was not associated with the event.119

In 1991, a PM sales manager reported that the Air Force MWR director said he would not accept tobacco sponsorships, “despite expected funding problems.”120 This policy was apparently rescinded, as MMM concerts were held on Air Force bases in 1992 and 1993. In 1996 a Navy policy prohibited tobacco brand sponsorship.121 However, the primary reason event sponsorship appears to have lessened dramatically in 1997, and halted by 2000, was the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA), which specified that tobacco companies could only sponsor one event per year.24 Military regulations required that events also be offered to civilians, thus the one event could not be military.

DISCUSSION

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s tobacco companies supplied military bases around the world with branded entertainment, targeting personnel—and their families and dependents—with intensive cigarette marketing. The events described here are only part of this picture, both because the documentary evidence is incomplete and because other promotions (e.g., advertising in military periodicals and coupon offers in military stores2) were also used. Furthermore, military officials volunteered extra services, suggested improvements, and expressed gratitude on behalf of the troops. Rarely, tobacco companies encountered resistance, despite regulations intended to limit their activities.

The types of promotion described in this study may be particularly salient in the military environment. Military personnel may be isolated from other entertainment, making events particularly meaningful.15 Event marketing is hypothesized to be particularly attractive to audiences predisposed to belonging to the “social community” or “neo-tribe” associated with the event; a concert on base, targeted to military personnel, exemplifies this aspect.122 Such events may build on military identity by emotionally attaching it to smoking and to the brand. The process by which individuals identify with advertised products may be enhanced by brand association with both the event and the military, in a three-way “co-branding.”123

Other studies have described the tobacco industry’s heavy focus on the inner city, using billboards, point of sale advertising, and van programs to create an environment saturated with tobacco promotion.57,124,125 Some have hypothesized that environments containing cues to smoke may increase uptake and inhibit cessation.126 This study suggests that for nearly 2 decades, military bases were such an environment, likely contributing to high rates of smoking among military personnel.

A military culture supportive of tobacco use has a long history; from the beginning of the 20th century to today, that culture has been shaped and sustained by the tobacco industry. The military was not a passive bystander, but actively helped create marketing that may still reverberate in the idea that smoking and tobacco use are part of military service.1 The support of MWR programs through tobacco sales further embeds support for tobacco use in military culture.

Although tobacco-brand event sponsorship is no longer occurring on military bases, it illustrates several issues for military tobacco control. First, vigilance may be required to ensure that policies are not revoked or undermined. Directive 1010.10 was released with much fanfare; its promotion restrictions were eased so quietly that even Philip Morris was not aware of it for some months. Furthermore, the new policy announcement purported only to reinterpret a directive about “Operational Policies for MWR Activities,” and made no reference to its effect on Directive 1010.10. Thus, even individuals alert to changes in health policy could have missed it.

Second, tobacco control policies must be framed so that they are supported by all personnel. It appears that many who were responsible for MWR programs did not perceive tobacco promotion to conflict with their mission of providing recreational activities. Similarly, military store personnel were interested in maintaining good business relationships with tobacco companies, not in tobacco control. Conflicting priorities led to a lack of support for the policy. Because tobacco use and sales are embedded in multiple military systems, policy must be defined as pertinent to everyone.

Finally, it should be noted that event sponsorship ceased only because of the MSA, not because of military policy change. The military should promulgate its own policies, both as a defense against external politics (e.g., the MSA benefited the military, but the military had no input into its negotiation) and to invite a sense of ownership by military personnel and thus contribute to an enhanced tobacco control climate.

Although some current military policies support prevention and cessation, others encourage tobacco use; for example, tobacco sales on base1 and the custom of “smoke breaks.”127 Such mixed messages are unlikely to be powerful enough to achieve desired reductions in tobacco use prevalence in the military. The elimination of a culture of military tobacco will require as much effort as its creation did. Given the now-established negative impact of tobacco use on military personnel even in the short term, and considering its previous role in creating a military culture that encouraged smoking, the DOD now has an obligation to take aggressive measures to make tobacco use unacceptable for military personnel.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, grant no. CA109153.

References

- 1.Bray RM, Hourani LL, Olmsted DLR, et al. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2005. Dec, [accessed May 12, 2009]. Department of Defense survey of health related behaviors among active duty military personnel: A component of the Defense Lifestyle Assessment Program (DLAP) 2006. Report no. DAMD17-00-2-0057. Available at http://stinet.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA465678&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joseph AM, Muggli ME, Pearson KC, Lando H. The cigarette manufacturers’ efforts to promote tobacco to the U.S. military. Milit Med. 2005;170(10):874–80. doi: 10.7205/milmed.170.10.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. A report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Office on Smoking and Health. Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 1995. Youth and tobacco: Preventing tobacco use among young people. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Defense. [accessed January 6, 2006];Population representation in the military services, Fiscal year 2002. 2003 Available at http://www.dod.mil/prhome/poprep2002/

- 5.Barbeau EM, Wolin KY, Naumova EN, Balbach E. Tobacco advertising in communities: associations with race and class. Prev Med. 2005;40(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balbach ED, Gasior RJ, Barbeau EM. RJ Reynolds’ targeting of African Americans: 1988–2000. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):822–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):908–16. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conway T, Cronan T. Smoking, exercise, and physical fitness. Prev Med. 1993;21:723–34. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90079-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zadoo V, Fengler S, Catterson M. The effects of alcohol and tobacco use on troop readiness. Milit Med. 1993;158(7):480–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helyer AJ, Brehm WT, Perino L. Economic consequences of tobacco use for the Department of Defense, 1995. Milit Med. 1998;163(4):217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klesges RC, Haddock CK, Chang CF, Talcott GW, Lando HA. The association of smoking and the cost of military training. Tob Control. 2001;10(1):43–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dall TM, Zhang Y, Chen YJ, et al. Cost associated with being overweight and with obesity, high alcohol consumption, and tobacco use within the military health system’s TRICARE prime-enrolled population. Am J Health Promot. 2007;22(2):120–39. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-22.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meenaghan T, Shipley D. Media effect in commercial sponsorship. Eur J Mark. 1999;33(34):328. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meenaghan T. Understanding sponsorship effects. Psychol Mark. 2001;18(2):95. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whelan S, Wohlfeil M. Communicating brands through engagement with ‘lived’ experiences. J Brand Manag. 2006;13(45):313–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwinner K. A model of image creation and image transfer in event sponsorship. Int Mark Rev. 1997;14(3):145. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tate C. Cigarette Wars: The Triumph of “The Little White Slaver”. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith EA, Blackman VS, Malone RE. Death at a discount: how the tobacco industry thwarted tobacco control policies in US military commissaries. Tob Control. 2007;16(1):38–46. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.017350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Defense. [accessed December 13, 2005];Directive number 1330.9: Armed services exchange policy, 2002. Updated November 21, 2003. Available at http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf2/d13309p.pdf.

- 20.Congressional Budget Office. [accessed May 12, 2009];The costs and benefits of retail activities at military bases, October 1997. Available at http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/1xx/doc158/retail.pdf.

- 21.Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense. Morale, welfare, and recreation program overview. Washington, DC: Department of Defense; May, 1984. Report no. DoD 1015.2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siemietkowski J. To infinity and beyond: expansion of the Army’s commercial sponsorship program. Army Lawyer. 2000 September;:24–40. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taft WH., IV . DoD Health Promotion Directive. Philip Morris; Mar 11, 1986. [accessed April 29, 2004]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hiz62e00. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Association of Attorneys General. [accessed March 3, 2009];Master Settlement Agreement. 1998 Available at http://www.naag.org/backpages/naag/tobacco/msa/msa-pdf/

- 25.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control. 2000;9(3):334–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor C. Theories of meaning. In: Taylor C, editor. Human Agency and Language: Philosophical Papers 1. Cambridge: New York: Cambridge University Press; 1985. pp. 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor C. Interpretation and the sciences of man. In: Taylor C, editor. Human Agency and Language: Philosophical Papers 2. Cambridge: New York: Cambridge University Press; 1985. pp. 33–81. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Manen M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill MR. Archival Strategies and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin RK. Case Study Research Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson LD. 860000 Kool Super Nights Concerts: Detailed Letter. Brown & Williamson; Feb 24, 1986. [accessed April 2, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ygt21c00. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds RJ. [accessed December 13, 2006];Military Initiative Program: Promotion plan update first quarter field marketing. 1990 February 8; Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/frb34d00.

- 33.Philip Morris. [accessed February 9, 2007];Marlboro Military/State Fair Tour 920000 Affiliate Guidelines. 1992 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jtm72e00.

- 34.Philip Morris. [accessed February 6, 2007];Events sponsored in PM USA brand names not included on 940000 or 950000 event calendars. 1995 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ixh18d00.

- 35.Brown & Williamson. [accessed April 2, 2007];Kool Military Super Nights Program. 1982 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nea40f00.

- 36.Miller RJ. Kool Super Nights Overseas. Brown & Williamson; Jan 20, 1984. [accessed July 17, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fcd01c00. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller R. Kool Super Nights/Panama. Brown & Williamson; Jun 13, 1984. [accessed December 12, 2006]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ouo73f00. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amos LC, Becker WA. Kool Super Nights poster & flier: Guam military. Brown & Williamson; Mar 23, 1984. [accessed July 17, 2007]. Out of home and point of sale media advertising submission memo. Ad no. M-1203 job no. 8601. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ddq21c00. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amos LC, Becker WA, Jarboe B, Miller RJ. Ad title Kool Super Nights: overseas military magazine (Okinawa) Brown & Williamson; Mar 23, 1984. [accessed July 17, 2007]. In home media advertising submission memo. Ad no. M-1215 job no. 8452. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bdq21c00. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schildmeyer S. Letter to A. Forsyth re: suggestions for KSN 1986. Brown & Williamson; Jul 22, 1985. [accessed July 18, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kyb70f00. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown & Williamson. [accessed January 29, 2007];1983 Programs. 1983 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cut50f00.

- 42.Montgomery WC. Memo to Special Markets Accounts Managers re: Kool Military Music Program. Brown & Williamson; Apr 13, 1984. [accessed January 29, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fkz01c00. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbell TS, Robinson K. Kool military music show Fort Knox, Kentucky. Brown & Williamson; Jun 9, 1983. [accessed January 29, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lvz13f00. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montgomery WB. To all special accounts managers re: Belair Bingo. Brown & Williamson; 1982. [accessed June 20, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cse70f00. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naughton N, Weatherly A. Observations of military promotions at Fort Scott. Brown & Williamson; Feb 20, 1984. [accessed June 23, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ilz13f00. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montgomery WB. To all special accounts managers re: Raleigh/Belair Bingo. Brown & Williamson; Nov 29, 1983. [accessed June 23, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bse70f00. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Telford GR. Newport Planning. Lorillard: Jan 26, 1983. [accessed June 20, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/koh41e00. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindsley V. Newport Fort Bragg Military Promotion. Lorillard: May 5, 1983. [accessed June 20, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ayx88c00. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lorillard. [accessed June 20, 2008];The Newport Alive with Pleasure: “Military Challenge”. 1983 April; Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fyx88c00.

- 50.Lindsley V. Newport’s Fort Bragg Military Promotion. Lorillard; Apr 25, 1983. [accessed June 20, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/byx88c00. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oliva G, Rakowski S, Ridgway SR. Summary of Lorillard Public Relations Activities 840400–840600. Lorillard; Jul, 1984. [accessed June 20, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/afs00e00. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lorillard. [accessed July 2, 2008];830000 Military Program Initial Concepts. 1983 January 9; Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ody88c00.

- 53.Lorillard. [accessed June 20, 2008];Military market. 1983 October; Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xdy88c00.

- 54.Wahl H. Newport San Diego Military Promotions. Lorillard; Aug 26, 1983. [accessed July 14, 2004]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mxx88c00. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lorillard. [accessed August 3, 2007];Newport Van Program. 1982 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ryx88c00.

- 56.Greene EJ. Government Sales: Newport Van Sampling Program. Lorillard; Dec 6, 1982. [accessed July 2, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bdy88c00. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yerger VB, Przewoznik J, Malone RE. Racialized geography, corporate activity, and health disparities: tobacco industry targeting of inner cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(4 Suppl):10–38. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hodges HM. Services agree on nine point action plan to help deglamorize cigarette smoking. Tobacco Institute; Apr 14, 1986. [accessed July 30, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vck40c00. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Philip Morris. [accessed July 26, 2007];Cigarette merchandising policy. 1986 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/igq85e00.

- 60.Alkire G. AFCOMS tobacco merchandising policy. Philip Morris; 1986. [accessed July 26, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qgq85e00. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Satterfield DE., III . RJ Reynolds; May 30, 1986. [accessed June 12, 2007]. Packet relating to cigarette merchandising policy in military commissaries. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eap35d00. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Philip Morris. [accessed July 25, 2008];State Tax and Smoking Restrictions Influences on Industry Volume (Update) 1988 April; Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pjk35e00.

- 63.RJ Reynolds. [accessed June 12, 2007];Military sales performance analysis, September 1986 (860900) Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ngv05d00.

- 64.Abene MR. 870000 Annual Military Report. Lorillard; Mar 15, 1988. [accessed July 25, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aip98c00. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Penninti V. Military Findings. Philip Morris; Jan 4, 1988. [accessed July 25, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kip48a00. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Penninti VR, Sakach J. Military Volume Trends. Philip Morris; Nov 20, 1987. [accessed July 25, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lip48a00. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Green GJ. Commercial Sponsorship of Morale, Welfare, and Recreation (MWR) Events. Philip Morris; Feb 29, 1988. [accessed July 25, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lae78a00. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilhelm R. DOD Policy Change. Philip Morris; Jul 11, 1988. [accessed July 25, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gnm98a00. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glennie L. Department of Defense Memo. Philip Morris; Jul 13, 1988. [accessed July 25, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/khl87a00. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wilhelm R. Marlboro Country Music. Philip Morris; Sep 19, 1988. [accessed July 25, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sqw78a00. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Philip Morris. [accessed January 30, 2007];Marlboro 90000 planning. 1990 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fdx65e00.

- 72.Philip Morris. [accessed January 30, 2007];Marlboro country music. 1994 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nqm72e00.

- 73.Philip Morris. Marlboro Music Military tour overview. Philip Morris; 1990. [accessed October 25, 2005]. (est.) Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qev96e00. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Murphy JA. Philip Morris; Jan 14, 1994. [accessed December 14, 2006]. Letters to MWR Directors at San Diego NS and and Corpus Christi NAS re: Marlboro Music concerts. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mwm87d00. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Charney S. Marlboro Country Music, Rota Spain. Philip Morris; Jul 24, 1989. [accessed July 25, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iaq78a00. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fontanez J. Marlboro Music 930000 military tour. Philip Morris; Jun 25, 1993. [accessed February 15, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ezj52e00. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stirlen R, Moore E. Marlboro Music Military. Philip Morris; Jun 21, 1994. [accessed October 25, 2005]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ngk72e00. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Charney S. Military ads [Marlboro Music Military tour] Philip Morris; Jun 4, 1990. [accessed January 30, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xkw65e00. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Robinson & Maites. Military marketing programs. Philip Morris; Apr 26, 1994. [accessed February 7, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fnm06e00. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cohen M. Retail posters: Marlboro Music Military concerts. Philip Morris; May 11, 1990. [accessed December 14, 2006]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sjf16e00. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Clawson S. Draft press release re: Marlboro Military concert at Naval Station San Diego. Philip Morris; Jun, 1994. [accessed February 15, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fwm87d00. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fontanez J. Fort Bliss Summerfest. Philip Morris; Aug 1, 1994. [accessed February 7, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hsx26c00. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ball D, Cohen C. Marlboro racing team t-shirt: elements. Philip Morris; Nov 29, 1990. [accessed June 20, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qsi32c00. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klockgether L. Commercial sponsorship agreement for MCAS El Toro. Philip Morris; Mar 3, 1994. [accessed September 4, 2003]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fna07e00. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Philip Morris. [accessed June 13, 2007];Notes re: Marlboro Racing party nights. 1991 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eql72e00.

- 86.Ball D. Marlboro promotions. Philip Morris; Jul 24, 1990. [accessed June 20, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tzt75e00. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Booher J. Marlboro Long Beach Grand Prix promotions. Philip Morris; Feb 7, 1994. [accessed June 20, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rbc66e00. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Philip Morris. [accessed July 11, 2008];Sales Promotion Planner 980000. 1998 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wqz32d00.

- 89.Mansmann J. 950000 Marlboro Van Program. Philip Morris; Jan 20, 1995. [accessed July 11, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yqw26c00. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Promotional Marketing, Inc. RJR military YAS initiative preliminary executional recommendations 1990 (900000) execution 1989 (890000) test market. RJ Reynolds; May 17, 1989. [accessed February 16, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qto24d00. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Therianos M. Camel notes Northeast exchange initiative program. RJ Reynolds; October/November, 1990. [accessed October 19, 2006]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aqk24d00. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Promotional Marketing, Inc. 1990 (900000) Exchange initiative program. Field marketing plan: Joe’s Squad. RJ Reynolds; Mar 30, 1990. [accessed December 4, 2006]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sro24d00. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Davis N. West Coast Exchange Initiative Program, October 1990 (901000) RJ Reynolds; [accessed October 19, 2006]. Camel Notes. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mqk24d00. [Google Scholar]

- 94.RJ Reynolds. [accessed October 25, 2006];Exchange initiative program. 1990 Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iqo24d00.

- 95.Sulick T. Letter to M.J. Gennaro re: Twenty-nine Palms concert. Philip Morris; Sep 14, 1994. [accessed January 29, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tlm87d00. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Valle DC. Letter to M.J. Gennaro, PM, re: Fort Huachuca concert results. Philip Morris; Aug, 1994. [accessed February 15, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/olm87d00. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Collins MK. Letter to J. Fontanez, PM, re: Naval Station San Diego concert results. Philip Morris; Aug, 1995. [accessed February 15, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lmm87d00. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Philip Morris. [accessed October 24, 2005];Report on Marlboro Music 1995 events. 1995 October 11; (est.). Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iul37c00.

- 99.Poss MA. Weekly review/update. RJ Reynolds; May 13, 1990. [accessed December 6, 2006]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cto24d00. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cohen M. Marlboro Country Music Military Spring tour status report. Philip Morris; May 5, 1989. [accessed October 25, 2005]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sxu82e00. [Google Scholar]

- 101.DeSilva F. RJ Reynolds; Nov 4, 1991. [accessed September 4, 2003]. Enclosed is a complete package of everything in Hawaii we did to advertise and promote RJR products. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/slz82d00. [Google Scholar]

- 102.DeSilva F. As you may know, we have designated the pit area for the JN Automotive Hydrofest at Pearl Harbor this year as the Smokin’ Joe’s pit. RJ Reynolds; Jul 25, 1995. [accessed October 31, 2005]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tbi61d00. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Broeman I, Cole AJ, Fontanez J. Philip Morris; Jul 11, 1995. [accessed October 25, 2005]. IMWRF-076 commercial sponsorship. Sponsorship log number 95066 Fort Bliss, Texas sponsorship agreement. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bfh63c00. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dominique LG. Sponsorship agreement. Philip Morris; 1996. [accessed February 12, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xeh63c00. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Philip Morris. [accessed January 30, 2007];Marlboro Music 900000 plan. 1990 February; Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sev96e00.

- 106.Philip Morris. [accessed February 6, 2007];Community event marketing 930423 weekly status report. 1993 April; Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dlu42e00.

- 107.Lenzi J. Marlboro Music/Military ban. Philip Morris; Jun 29, 1994. [accessed October 25, 2005]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/smv26c00. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cohen M, Greece H. Marlboro Country Music Military Spring tour status report Fort Sill and Fort Carson. Philip Morris; May 31, 1989. [accessed January 30, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ktt75e00. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Philip Morris. [accessed January 29, 2007];United States MAMI company performance 930400. 1993 June; Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xsj03e00.

- 110.Robertson TW. Significant activity report. RJ Reynolds; May 29, 1991. [accessed October 10, 2006]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nvi83d00. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Coombs B. Worldwide military status report 000500. Philip Morris; Jun 20, 1991. [accessed October 10, 2006]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/erp05e00. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gordon P, Parrack ET. Letter to promoter re: Kool Military Music Sampling program. Brown & Williamson; Jul 17, 1981. [accessed January 29, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rjt40f00. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Matteson MM. Military music. Brown & Williamson; May 14, 1981. [accessed January 29, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tsm21c00. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vangender C. Military Sampling. Lorillard; Nov 15, 1983. [accessed July 2, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uyx88c00. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lorillard. [accessed August 3, 2007];Van military sampling. 1983 December 9; Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/syx88c00.

- 116.Van Genderen C. Military sampling. Lorillard; Dec 8, 1983. [accessed August 3, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tyx88c00. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ward T. Kool Super Night program. Brown & Williamson; 1986. [accessed July 18, 2007]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aht21c00. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brown & Williamson. [accessed April 2, 2007];Q&A re: cancellation of Fort Benning Kool Super Night. 1986 May 27; Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yst21c00.

- 119.Boyd JS. Sponsorship of Recreational Activities by Tobacco and Alcoholic Beverage Companies. Philip Morris; May 20, 1988. [accessed July 25, 2008]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fjq87a00. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Glennie L. Worldwide military status report 000900. Philip Morris; Oct 15, 1991. [accessed October 10, 2006]. Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qbr93e00. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Marsh L. Prohibition of tobacco product commercial sponsorship. Philip Morris; Nov 19, 1996. [accessed October 25, 2005]. (est.) Available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/geh63c00. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wohlfeil M, Whelan S. Consumer motivations to participate in marketing-events: the role of predispositional involvement. In: Ekstrom KM, Brembeck H, editors. European Advances in Consumer Research. Goteborg, Sweden: Association for Consumer Research; 2006. pp. 125–30. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Smith G. Brand image transfer through sponsorship: a consumer learning perspective. J Market Manag. 2004;20(34):457. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Stoddard JL, Johnson CA, Sussman S, Dent C, Boley-Cruz T. Tailoring outdoor tobacco advertising to minorities in Los Angeles County. J Health Commun. 1998;3(2):137–46. doi: 10.1080/108107398127427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Moore DJ, Williams JD, Qualls WJ. Target marketing of tobacco and alcohol-related products to ethnic minority groups in the United States. Ethn Dis. 1996;6(1–2):83–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Baumann SB, Sayette MA. Smoking cues in a virtual world provoke craving in cigarette smokers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20(4):484–9. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Haddock CK, Hoffman KM, Peterson A, et al. Factors which influence tobacco use among junior enlisted in the United States Army and Air Force: a formative research study. Am J Health Promot. 2009;23(4):241–6. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.070919100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]