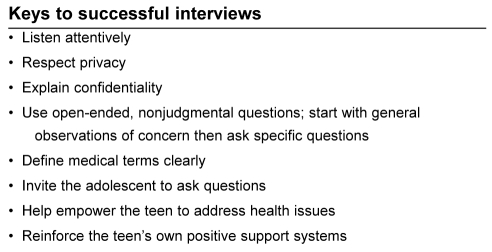

Adolescents obtain their health information from a number of sources. Health care providers are high on the list of the most valued of these sources. Therefore, clinicians need to continue to develop their approach and communication skills with their adolescent patients. One of the challenges of adolescent medicine is helping your patients in finding a path to a healthy lifestyle they are comfortable with. It is essential for you to get the information you need to assess and diagnose health issues, and for the patient to get the information he/she needs to deal effectively with (these) health issues. Adolescents want very much to show they are mature and ‘can handle things themselves’, but at the same time, some of the medical and psychosocial issues they confront may require them to be more dependent. The health care provider must deliver information in such a way as to allow the patient to participate in their own care to the limit of their capabilities developmentally, physically and emotionally, whether they have a short term, chronic or life-threatening condition (1).

In addition to the young person who presents with a specific complaint, the physician has much to discuss with ‘healthy’ youth in the office. It is in fact during these adolescent years that behaviour such as eating habits, safe sex practices and physical activity regimens become established. It is also at this time that decisions concerning alcohol and substance use are often made.

This article will discuss communication skills needed to work with youth, some suggestions on initial approaches to these patients, information gathering strategies, successful involvement of the family and other supportive individuals, and how we can help youth make informed decisions about their care and treatment. A previous Canadian Paediatric Society statement entitled “Office guidelines for the care of adolescents” details how the office/clinic can be more welcoming and comfortable for adolescents (2).

CONFIDENTIALITY

Confidentiality is the cornerstone of any therapeutic relationship with youth. Without clarifying the limits of confidentiality you may well get incorrect or incomplete information during your history taking. Physicians are often concerned about treating adolescents without parental or guardian consent for fear of being sued. However, the common law in Canada clearly states that a minor can give informed consent to therapeutic medical treatment providing they can understand the information regarding the proposed treatment and can appreciate the attendant risks and possible consequences. There are variations of this issue in the various provinces. For further details, see the Morton and Westwood article entitled “Informed consent in children and adolescents” published in 1997 (3).

Some physicians start the interview with an adolescent by detailing the law and the facts of confidentiality and its exceptions in the circumstances of serious thoughts of homicide or suicide, or recent physical or sexual abuse. This may be repeated often at subsequent visits. It is possible to get the youth to disclose to the family something that is appropriate or that would be helpful for them to know; however, this may take some time.

The confidentiality of the visit is reinforced by having the interview in a room that ‘feels’ private, ie, with a door, not a curtain, and far enough away from the waiting area so that the discussion cannot be overheard. It is also often best to have individual files for each member of the family.

OBTAINING INFORMATION

There are a number of approaches to seeing adolescents in the office and the physician should find one with which they are comfortable. If the adolescent has been a patient since childhood, the physician needs to make the youth and the parent aware of the change in relationship as the young person matures. Continuity of care is a strong building block to the therapeutic alliance, but adolescents are willing to rebuild a relationship with a new person who shows them respect and will listen to their concerns. Ask for school reports as available. Report cards are often invaluable in getting information on the youth’s attendance or late record, as well as seeing any significant shifts in behaviour and/or performance with respect to school.

Part or all of the visits, especially during history taking, should be without the parent present. However, in most cases it is essential to speak with the parents to discuss their concerns and define any issues they may have about parenting adolescents. Some useful references for parents are included in the bibliography.

The sex of the physician may be important to the comfort of some patients. Some girls prefer to consult with a female physician for discussions and necessary physical examinations around sexuality and contraception issues, while boys may wish to see a male physician instead. The opportunity to change physicians should be brought up by the doctor. However, we believe the health care professional’s comfort with the adolescent is much more important than their sex, and the adolescent will often respond to this.

Some physicians start the visit with the adolescent and parent(s) and then ask the parent(s) to leave for the second part of the interview and/or the physical examination. Reasons for this approach are:

frequently the adolescent will not give (or may not know) the reason for the visit (eg, “I don’t know why I am here” or “my mother brought me”);

spending time with the adolescent and his/her parent speeds up information gathering in a busy office or clinic; and

the interaction of the adolescent and parent (conflict or empathy, etc) can be observed.

Some prefer to see the adolescent alone first and have the parent join them later. This approach allows:

the adolescent to feel his/her concerns will ‘really’ be heard;

the adolescent to learn to speak directly to the health care professional, something they may not have done before;

the adolescent to have the terms of confidentiality explained and to increase trust in the health care professional; and

the adolescent to tell his/her issues without adding the emotional content of the complaint to detract at this early stage of history taking.

A useful adjunct to this second approach is to have the parents write a letter about their concerns and send it to the office before the visit. In the case where one parent is unable to attend, this allows for input from both parents. Also, if the adolescent does not mention these concerns, the doctor may ask about them in a less threatening way without the parents present.

Some adolescents bring a friend as a companion to the visit. If they actually want the friend with them during the visit because this may make them feel more at ease, it is appropriate to agree. However, it is important for the youth to understand that as part of the acceptance of their new mature role in their health care, they should expect to see the health professional alone for part or all of the visit this time or in the future. This privacy will allow for more confidentiality and a chance to take a more detailed history.

THE PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVIEW

The Home, Education/Employment, Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Safety, (violence and abuse), and Suicide (HEADSSS) mnemonic is very useful to remind us of important information we need to obtain from adolescent patients. This approach starts with nonthreatening, open-ended, nonjudgmental questions and progresses to more sensitive areas such as sexuality, feelings of depression and thoughts of suicide. The discussion of the presenting complaint or reason for the visit should be addressed at some time during the visit even if other important issues are brought forward. Explain that all the questions are asked in an attempt to help the adolescent improve their health.

Questions around the HEADSSS interview are discussed in more detail in the reference below but a few will be outlined (4). Although there is a ‘standardized’ HEADSSS, many modifications have been used to individualize it to a specific patient. In the list below, questions about body image and dieting have been added to use when appropriate.

Home

Where, who lives there? How do the people in your family get along?

Do you argue with your parents?

Do you feel safe at home?

Education/Employment

Do you feel safe at school?

Performance at school (report card if possible).

Do you have a job? How many hours?

Have you ever failed or repeated a grade?

Have you ever been suspended?

Activities

What do you and your friends do for fun?

What are your hobbies?

Do you participate in sports?

Have you ever been in trouble with the law?

What would you like to do after you finish school?

Drugs and dieting

Do you or your friends often drink or smoke pot at parties?

Do you ever drink or smoke pot alone?

Have you ever been in a car driven by someone who was drunk or high?

Have you ever tried any other drugs?

Are you satisfied with your weight? Have you ever dieted, exercised or used drugs to change your weight?

Sexuality – do not assume heterosexuality

Do you have any concerns about your physical/sexual development?

Are you dating? How long have you been together?

Have you ever had sex? Are you sexually active now? How often do you have sex?

What was your age when you first had sex?

Have you used protection for sexually transmitted diseases or birth control?

Have you ever been pregnant?

Have you ever been forced to have sex?

Suicide (and depression)

Do you feel down or depressed much of the time?

For how long have you felt this way?

Have you thought of hurting yourself?

Have you ever tried to harm yourself?

Safety (violence and abuse)

Have you ever seen or been the victim of violence?

Is there a gun in your home?

Have you ever been in trouble with the law?

Do you have use of a car? Do you wear a seat belt?

This HEADSSS approach has been found to help uncover areas of concern or distress and allows us to identify protective factors and support systems that may be used to foster resiliency and health-promoting practices for youth. It also allows for the clinician to provide accurate and important information to the adolescent even if certain risk behaviours are denied.

Helping the adolescent give up risky behaviours or choose healthy ones is a very important role for the clinician. Building decision-making skills is the cornerstone of this task. The PASTE mnemonic is useful in teaching these skills and may be demonstrated with a number of problems that the adolescent may be facing.

P problem – define the problem

A alternatives – list possible alternative solutions and list their pros and cons

S select an alternative

T try it (help in how to do this may be needed [eg, how to increase your chance of successfully quitting smoking or being abstinent])

E evaluate your choice and modify it as needed, or even reselect

Many adolescents make the transition to adulthood without a lot of stress or turmoil. However, it is important for the health care professional to identify problems and develop an approach to treatment for those patients who need help during this time. It is important not to pass up problems as issues that the youth ‘will grow out of it’. It is important to identify the adolescent’s strengths and support system. Learning and using a few special techniques to communicate with youth make this medical intervention easier and often more successful.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the Adolescent Health Committee of the Canadian Paediatric Society for their assistance and suggestions with this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coupey SM. Interviewing adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44:1349–64. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70563-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Paediatric Society Office practice guidelines for the care of adolescents<www.cps.ca/english/statements/am/am94-04.htm> (Version current at October 16, 2003).

- 3.Morton WJ, Westwood J. Informed consent in children and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health. 1997;2:329–33. doi: 10.1093/pch/2.5.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrman WG, Matson SC. Approach to adolescents on serious or sensitive issues. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45:189–204. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BIBLIOGRAPHY - For clinicians

- 1.Frazar GE. A private practitioner’s approach to adolescent problems. Adolescent medicine. State of the Art Reviews. 1998;9:229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKenzie RG. Approach to the adolescent in the clinical setting. Med Clin North Am. 1990;74:1085. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30503-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caring for kids. <www.caringforkids.cps.ca> (Version current at September 23, 2003).

- 4.The Society for Adolescent Medicine <www.adolescenthealth.org> (Version current at September 23, 2003).

BIBLIOGRAPHY - For parents and adolescents

- 1.Steinberg L, Levine A. New York: Harper Perennial, Harper Collins; 1997. You And Your Adolescent: A Parent’s Guide For Ages 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slap GB, Jablow MM. Teenage Health Dare: The First Comprehensive Family Guide For The Preteen To Young Adult Years. New York: Pocket Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caring for kids. <www.caringforkids.cps.ca> (Version current at September 23, 2003).