Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Current guidelines for ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) recommend performing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 90 min of hospital arrival. However, recent data suggest that in a real-world setting, median door-to-balloon (DTB) time is closer to 180 min for transfer patients, with less than 5% of patients being treated within 90 min. A retrospective observational study was conducted to assess time to treatment in patients undergoing primary PCI at the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute (QHLI).

METHODS:

Consecutive lytic-eligible patients undergoing primary PCI at the QHLI for STEMI between April 2004 and March 2005 were included in the present analysis. The primary evaluation was DTB time measured from arrival at the first hospital to first balloon inflation. Clinical outcomes were in-hospital death, reinfarction and bleeding. DTB times and hospital outcomes of patients transferred from referring hospitals were compared with those of patients presenting directly to the QHLI.

RESULTS:

During the study period, 203 lytic-eligible patients were treated with primary PCI. Sixty-nine patients presented directly to the QHLI and 134 were transferred from other hospitals. Six transfer patients were excluded because of missing time variables. The median DTB time was 114 min in transfer patients, compared with 87 min in patients presenting directly to the QHLI (P<0.001). DTB time was less than 90 min in 24% of the transfer population compared with 55% of patients presenting directly to the QHLI (P<0.001). In patients referred from hospitals within a radius of 30 km from the QHLI (n=100), median DTB time was 106 min with 30% receiving PCI within 90 min. In these patients, estimated PCI-related delay was 74 min. For patients presenting to hospitals beyond 30 km (n=28), median DTB time was 142 min with 4% receiving reperfusion within 90 min. In these patients, estimated PCI-related delay was 110 min. Median DTB time for patients presenting during off hours at the QHLI was 92 min compared with 79 min for patients presenting during regular business hours (P=0.02). In patients transferred from other hospitals, median DTB time was 118 min during off hours and 108 min during normal business hours (P=0.07).

CONCLUSIONS:

A DTB time of less than 90 min can be achieved in the majority of patients presenting directly to a primary PCI centre. However, for patients presenting to community hospitals, transfer for primary PCI is often associated with delayed revascularization. The present study highlights the need for careful patient selection when deciding between on-site thrombolytic therapy and transfer for primary PCI for STEMI patients presenting to hospitals without PCI facilities.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndromes, Angioplasty, Myocardial infarction, Stent

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

D’après les lignes directrices courantes en cas d’infarctus du myocarde avec élévation du segment ST (IMEST), il faut procéder à une intervention coronaire percutanée (ICP) primaire dans les 90 minutes suivant l’arrivée à l’hôpital. Cependant, de récentes données laissent supposer qu’en milieu réel, le délai médian entre l’arrivée et l’insertion du ballonnet (AIB) se rapproche davantage de 180 minutes dans le cas de patients transférés, moins de 5 % des patients étant traités dans un délai de 90 minutes. Les auteurs ont mené une étude d’observation rétrospective pour évaluer le délai jusqu’au traitement chez les patients subissant une ICP primaire à l’Institut de cardiologie et de pneumologie de Québec (ICPQ).

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les patients consécutifs admissibles à un traitement lytique qui ont subi une ICP primaire à l’ICPQ en raison d’un IMEST entre avril 2004 et mars 2005 ont participé à la présente analyse. L’évaluation primaire était le délai entre l’AIB mesuré à compter de l’arrivée au premier hôpital jusqu’au premier gonflage de ballonnet. Les issues cliniques étaient un décès en milieu hospitalier, un nouvel infarctus et une hémorragie. Les auteurs ont comparé le délai entre l’AIB et l’issue à l’hôpital des patients transférés d’autres hôpitaux avec ceux des patients qui arrivaient directement à l’ICPQ.

RÉSULTATS :

Pendant la période de l’étude, 203 patients admissibles à un traitement lytique ont subi une ICP primaire. Soixante-neuf patients sont arrivés directement à l’ICPQ et 134 ont été transférés d’autres hôpitaux. Six patients transférés ont été exclus en raison de l’absence des variables reliées aux délais. Le délai médian entre l’AIB était de 114 minutes chez les patients transférés, par rapport à 87 minutes chez ceux qui étaient arrivés directement à l’ICPQ (P<0,001). Le délai entre l’AIB était inférieur à 90 minutes chez 24 % de la population transférée, par rapport à 55 % des patients arrivant directement à l’ICPQ (P<0,001). Chez les patients provenant d’un hôpital situé dans un rayon de 30 kilomètres de l’ICPQ (n=100), le délai médian entre l’AIB était de 106 minutes, 30 % recevant l’ICP dans le délai de 90 minutes. Chez ces patients, le délai estimatif relié à l’ICP était de 74 minutes. Dans le cas des patients provenant d’un hôpital situé à plus de 30 kilomètres (n=28), le délai médian entre l’AIB était de 142 minutes, 4 % recevant une reperfusion dans un délai de 90 minutes. Chez ces patients, le délai estimatif relié à l’ICP était de 110 minutes. Le délai médian entre l’AIB chez les patients arrivant à l’ICPQ après les heures normales était de 92 minutes, par rapport à 79 minutes chez les patients qui arrivaient pendant les heures normales (P=0,02). Chez les patients transférés d’autres hôpitaux, le délai médian entre l’AIB était de 118 minutes après les heures normales, et de 108 minutes pendant les heures normales (P=0,07).

CONCLUSIONS :

Il est possible d’obtenir un délai inférieur à 90 minutes entre l’AIB chez la majorité des patients qui arrivent directement à un centre d’ICP primaire. Cependant, pour les patients qui se présentent à un hôpital général, le transfert pour subir l’ICP primaire s’associe souvent à un délai de revascularisation. La présente étude souligne le besoin d’une sélection attentive des patients au moment de choisir entre une thérapie thrombolytique sur place et le transfert pour subir l’ICP primaire chez les patients de l’ICPQ qui arrivent dans des hôpitaux sans installations d’ICP.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), when compared with thrombolytic therapy for acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), results in higher rates of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction-3 flow and lower rates of reinfarction, stroke and death (1). Yet, primary PCI is not readily accessible to all patients, especially in those presenting to hospitals without on-site PCI facilities. Physicians treating these patients face two options: immediate treatment with fibrinolytic therapy or transfer for primary PCI at a tertiary centre.

Many studies have shown that transferring STEMI patients is safe, and that the benefits of primary PCI over thrombolytic therapy are conserved when transfer delays are reasonable (2–5). Based on randomized, controlled trials, the current guidelines for STEMI recommend a door-to-balloon (DTB) time of less than 90 min when performing primary PCI, including transfer time (6–8). However, recent data from the United States National Registry of Myocardial Infarction suggest that in a real-world setting, DTB delays are much longer, with a median DTB time of 183 min and with less than 5% of patients being treated within 90 min (9). A recent study (10) conducted in the province of Quebec reached similar findings.

The importance of timely intervention when treating STEMI patients is undisputed. This rule also applies to transfer patients. DTB times of less than 2 h in patients transferred for primary PCI are associated with improved survival, less recurrent ischemia and angina, less cardiogenic shock and a shorter hospital stay (11). Furthermore, recent analyses (12–14) suggest that the benefits of primary PCI over thrombolytic therapy vanish as PCI-related delays increase. For these reasons, treatment delays must be taken into account when deciding between thrombolytic therapy and transfer for primary PCI.

To verify the timeliness of reperfusion therapy in patients suffering acute STEMI in Quebec City, Quebec, a retrospective observational study assessing time to treatment and the factors involved in treatment delays in patients undergoing primary PCI was conducted at the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute (QHLI).

METHODS

Study population

All patients undergoing primary PCI at the QHLI for STEMI between April 1, 2004, and March 31, 2005, were considered for inclusion in the study. Patients in cardiogenic shock, patients without chest pain on presentation or with chest pain of more than 12 h duration, patients who received fibrinolytic therapy and patients who had a contraindication to fibrinolysis were excluded from the analysis.

Clinical data and outcome measures

Clinical and demographic characteristics were extracted by chart review. The following time points were recorded: time of symptom onset, time of arrival at the initial hospital (first-door time), time of first electrocardiogram (ECG), time of arrival in the catheterization laboratory and time of first balloon inflation. When the first ECG was not diagnostic of STEMI, the time of the first ECG with 1 mm or greater ST segment elevation in two or more contiguous leads was used as the first-door time. For transferred patients, we reviewed the ambulance records to collect the time of ambulance call and to determine transfer delays. The catheterization laboratory database was reviewed for PCI-related time points.

The primary evaluation was total DTB time, measured from arrival at the first hospital to first balloon inflation (or time when Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 2 or 3 flow was achieved in the culprit vessel, whichever occurred first). Other evaluations included first door-to-ambulance call (an estimation of what would have been the ‘door-to-needle’ time) and PCI-related delay. PCI-related delay was estimated by subtracting door-to-ambulance call from the total DTB time.

All ischemic events were recorded. In-hospital death was defined as any death occurring during the index hospital stay. Recurrent reinfarction was defined as recurrent symptoms compatible with acute myocardial infarction together with a new creatine kinase-MB rise above the upper limit of normal. Bleeding complications were recorded, and access site complications were considered when the nurse or physician noted a hematoma larger than 2 cm at the site of puncture. Need for blood transfusion was also recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as a number (percentage) for categorical variables and as a median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) for continuous variables. Time delays for transfer patients were compared with those of patients presenting directly to the QHLI. Also, time delays for transfer patients presenting to hospitals outside a radius of 30 km from the PCI site were compared with those of transfer patients presenting to hospitals within a radius of 30 km from the QHLI. This distance was chosen because it corresponds roughly to a 30 min transfer time between hospitals. If it is assumed that it takes an average of 30 min to perform balloon inflation after arrival at the PCI centre, then 30 min is the maximum acceptable transfer time to achieve a PCI-related delay of less than 60 min, as suggested by current guidelines. Finally, treatment delays for patients presenting outside normal business hours were compared with those of patients presenting during regular duty hours. Normal duty hours in the present study were from Monday to Friday between 8h00 and 17h00, excluding holidays. Differences in means were assessed with Student’s t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test, depending on the variable distribution. χ2 tests and Fisher’s exact test were used to assess differences in proportions. P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

During the study period, 203 patients met the inclusion criteria. Sixty-nine patients presented directly to the QHLI and 134 patients were transferred from referring hospitals. All relevant time points were available for patients presenting at the QHLI. Six transfer patients had missing hospital admission times and were excluded from the analysis. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Compared with transfer patients, patients presenting directly to the QHLI were more likely to have a history of cardiovascular disease and to suffer from high blood pressure, and were less likely to present with an anterior myocardial infarction. PCI was performed from the radial artery in greater than 93% of patients.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients presenting directly to the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute (QHLI) and patients transferred from referring hospitals

| Patient characteristic | QHLI (n=69) | Referring hospitals (n=128) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 58 (52, 71) | 59 (49, 69) | 0.7 |

| Men, n (%) | 51 (74) | 97 (76) | 0.9 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 36 (52) | 40 (31) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 13 (19) | 19 (15) | 0.5 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 35 (51) | 69 (54) | 0.8 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 27 (39) | 44 (34) | 0.5 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 27 (39) | 48 (38) | 0.9 |

| Previous CAD, PCI or CABG, n (%) | 14 (20) | 7 (5) | 0.001 |

| MI location, n (%) | |||

| Anterior | 15 (22) | 46 (36) | 0.05 |

| Nonanterior | 54 (78) | 82 (64) | 0.05 |

| Vascular access, n (%) | |||

| Radial | 64 (93) | 120 (94) | 0.8 |

| Femoral | 3 (4) | 8 (6) | 0.8 |

| Humeral | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.1 |

Values are given as median (25th percentile, 75th percentile). CABG Coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD Coronary artery disease; PCI Percutaneous coronary intervention; MI Myocardial infarction

The median time from the initial hospital arrival to the first balloon inflation was 114 min among transfer patients, compared with 87 min among patients presenting directly to the QHLI (P<0.001; Table 2). Total DTB time was 90 min or less in 24% of the transfer population compared with 55% of patients presenting directly to the QHLI (P<0.001). For patients presenting to non-PCI hospitals, the median first door-to-ambulance call time was 29 min (20 min, 45.5 min [25th and 75th percentile, respectively]) and the median estimated PCI-related delay was 79.5 min (66 min, 95 min).

TABLE 2.

Time delays in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) grouped according to hospital of first contact

| QHLI (n=69) | Referring hospitals (n=128) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median delays, min* | |||

| Total door-to-balloon time | 87 (74, 110) | 114 (91, 141) | <0.0001 |

| First door to ECG | 10 (6, 18) | 9 (3.5, 15.5) | 0.3 |

| First door to ambulance call | NA | 29 (20, 46.5) | NA |

| Ambulance call to QHLI door | NA | 40 (32, 48) | NA |

| QHLI door to cath lab door | 54 (46, 72) | 9 (6, 16) | <0.0001 |

| Cath lab door to balloon | 30 (22, 36) | 29 (21, 34) | 0.3 |

| Door-to-balloon time, n (%) | |||

| ≤60 min | 9 (13) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 |

| ≤90 min | 38 (55) | 31 (24) | <0.0001 |

| ≤120 min | 58 (84) | 74 (58) | <0.0001 |

| ≤180 min | 67 (97) | 115 (90) | 0.09 |

Values are given as median (25th percentile, 75th percentile). Cath lab Catheterization laboratory; ECG Electrocardiogram; NA Not applicable; QHLI Quebec Heart and Lung Institute

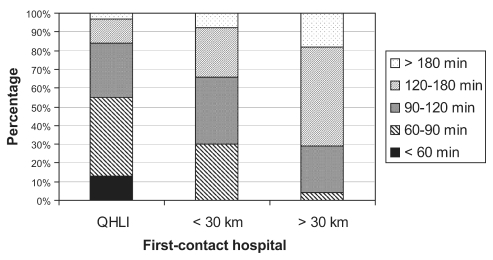

Among patients referred from hospitals inside a radius of 30 km from the QHLI (n=100), the median DTB time was 106 min (87 min, 132 min), with 30 patients (30%) receiving PCI within 90 min (Table 3). For these patients, the estimated PCI-related delay was 74 min (63 min, 86 min). Among patients presenting to hospitals beyond a radius of 30 km (n=28), the median DTB time was 141.5 min (119 min, 167 min), with only one patient (3.6%) receiving reperfusion within 90 min (Figure 1). For these patients, the estimated PCI-related delay was 110 min (92 min, 136 min).

TABLE 3.

Time delays in transfer patients according to distance of referring hospital

| Distance from QHLI | ≤30km (n=100) | >30 km (n=28) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median delays, min* | |||

| Total door-to-balloon time | 106 (87, 132) | 141.5 (119, 167) | <0.0001 |

| First door to ECG | 10 (4, 17) | 5 (3, 12) | 0.04 |

| First door to ambulance call | 28 (20, 48) | 30 (24, 41) | 0.6 |

| Ambulance call to QHLI door | 36 (30, 42) | 52.5 (49, 65) | <0.0001 |

| QHLI door to cath lab door | 8.5 (6, 15) | 15 (6, 24) | 0.1 |

| Cath lab door to balloon | 28 (21, 34) | 30.5 (23, 40) | 0.1 |

| Door-to-balloon time, n (%) | |||

| ≤60 min | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| ≤90 min | 30 (30) | 1 (4) | 0.002 |

| ≤120 min | 66 (66) | 8 (29) | 0.001 |

| ≤180 min | 92 (92) | 23 (82) | 0.2 |

Values are given as median (25th percentile, 75th percentile). Cath lab Catheterization laboratory; ECG Electrocardiogram; QHLI Quebec Heart and Lung Institute

Figure 1).

Distribution of patients according to door-to-balloon time and hospital of initial presentation. QHLI Quebec Heart and Lung Institute

DTB times for patients presenting outside regular business hours and during weekends are shown in Table 4. The median DTB time for patients presenting during off hours at the QHLI was 92 min (78.5 min, 111.5 min) compared with 79 min (51 min, 101 min) for patients presenting during regular business hours (P=0.02). Among patients transferred from other hospitals, the median DTB time was 117.5 min (93 min, 151 min) during off hours and 107.5 min (87 min, 127 min) during business hours (P=0.07).

TABLE 4.

Delays according to time of presentation (business hours versus off hours)

|

QHLI (n=69) |

Referring hospitals (n=128) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Off hours (n=43) | Business hours (n=26) | P | Off hours (n=78) | Business hours (n=50) | P | |

| Total door-to-balloon time, min* | 92 (78, 111) | 79 (51, 101) | 0.02 | 117.5 (93, 150) | 107.5 (87, 127) | 0.07 |

| First door to electrocardiogram | 9 (6, 15) | 15 (5, 24) | 0.3 | 9 (3, 14) | 10 (4, 17) | 0.7 |

| First door to ambulance call | NA | NA | NA | 31(20, 50) | 25.5 (19, 42) | 0.3 |

| Ambulance call to QHLI door | NA | NA | NA | 40 (31, 48) | 38 (33, 47) | 0.9 |

| QHLI door to cath lab door | 62 (50, 76) | 42 (30, 61) | 0.003 | 8 (6, 17.5) | 11 (7, 16) | 0.9 |

| Cath lab door to balloon | 30 (24, 36) | 27 (24, 37) | 0.4 | 29 (22, 35) | 26 (20, 34) | 0.2 |

| Door-to-balloon time, n (%) | ||||||

| ≤60 min | 0 (0) | 9 (35) | <0.0001 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| ≤90 min | 21 (49) | 17 (65) | 0.2 | 16 (21) | 15 (30) | 0.3 |

| ≤120 min | 36 (84) | 22 (85) | 1.0 | 41 (53) | 33 (66) | 0.1 |

| ≤180 min | 42 (98) | 25 (96) | 1.0 | 67 (86) | 48 (96) | 0.08 |

| >180 min | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 1.0 | 11 (14) | 2 (4) | 0.08 |

Values are given as median (25th percentile, 75th percentile). Cath lab Catheterization laboratory; NA Not applicable; QHLI Quebec Heart and Lung Institute

Clinical follow-up

During their hospital stay, three patients died – one who presented directly to the QHLI and two who transferred from other hospitals (Table 5). The reinfarction rate was higher in the QHLI group, with four patients (6%) experiencing a second myocardial infarction compared with none in the transfer group (P=0.01). Bleeding complications other than access site hematoma occurred more frequently in patients presenting directly to the QHLI (6%) than in transfer patients (1%; P=0.05).

TABLE 5.

In-hospital clinical events

| In-hospital events | QHLI (n=69) | Other hospitals (n=128) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse clinical events, n (%) | |||

| Death | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1.0 |

| Reinfarction | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.01 |

| Pulmonary edema or shock | 3 (4) | 7 (5) | 1.0 |

| Transient ischemic attack or stroke | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0.5 |

| Embolism | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.0 |

| Coronary dissection | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.0 |

| Radial artery thrombosis | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.4 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.0 |

| Bleeding complications, n (%) | |||

| Red blood cell transfusion | 2 (3) | 3 (2) | 1.0 |

| Access site hematoma | 11 (16) | 18 (14) | 0.8 |

| Other bleeding complications | 4 (6) | 1 (1) | 0.05 |

QHLI Quebec Heart and Lung Institute

DISCUSSION

According to the results of the present retrospective study, most patients presenting directly to the QHLI with STEMI are treated within the recommended DTB time of 90 min. However, reperfusion delays are longer in patients transferred from other hospitals, especially when patients are transferred from hospitals outside a radius of 30 km from the QHLI catheterization laboratory. The present analysis suggests that up to 70% of patients transferred from hospitals in proximity to the QHLI (ie, less than 30 km) and up to 94% of patients transferred from hospitals outside a radius of 30 km from the QHLI do not receive primary PCI within 90 min. The results achieved in patients transferred from nearby hospitals are somewhat encouraging in comparison with the treatment delays observed for transfer patients in the United States National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (9) and the AMI-QUEBEC study (10). Also, although it was longer than current recommendations (ie, less than 60 min), the median 74 min estimated PCI-related delay for patients referred from nearby hospitals is similar to the average 73 min PCI-related delay observed in trials evaluating transfer for primary PCI (5). This is also well within the 110 min to 114 min PCI-related delay at which primary PCI is expected to lose its mortality benefit over thrombolytic therapy (13,14). On the other hand, the 110 min estimated PCI-related delay for patients transferred from remote hospitals was longer than in previous randomized clinical trials (3,4).

In the present study, DTB times were shorter for patients presenting during normal business hours than for patients presenting during weekends or outside normal duty hours. This was particularly evident for patients presenting directly to the QHLI, in which the median DTB time was 13 min longer for patients presenting during off hours. This is consistent with the results of a previous study (15) reporting an additional delay of 21 min in the median DTB time for patients presenting during off hours. Nonetheless, the median DTB time in STEMI patients presenting during off hours to the QHLI was close to the 90 min target.

Evaluation of individual components of the total DTB time revealed that the median door-to-ambulance call time (an estimation of what would have been the door-to-needle time) was 29 min, which is within the current recommendations of less than 30 min. Also, it was noted that the median delay between catheterization laboratory arrival and balloon inflation was also 29 min. Consequently, to achieve the recommended DTB time of less than 90 min, the total transfer time (catheterization laboratory arrival time minus ambulance call for transfer time) must be less than 32 min. Because significant improvement in door-to-ambulance call and catheterization laboratory delays are unlikely, every effort should be made to reduce transfer time. Standardized transfer protocols should be implemented, and transfer of STEMI patients for primary PCI should be given first priority by the ambulance crew. The decision to transfer patients should be made by the emergency room physician, avoiding unnecessary cardiology consult before transfer. These improvements were realized in Quebec City during the course of the present evaluation. Also, vigilant patient selection based on patient characteristics and a realistic evaluation of transfer time should be made by the emergency room physician. When total transfer time is expected to be longer than 30 min, physicians should assess whether thrombolytic therapy may be a better reperfusion strategy than primary PCI. In particular, young patients presenting early in the course of an STEMI may fare better with thrombolytic therapy when PCI is not readily available (14).

In the past several years, important progress was made in the care of STEMI patients in Quebec City. As part of a quality improvement initiative, prospective data collection has been implemented to monitor advances in treatment delays. Currently, most but not all patients receive timely reperfusion with primary PCI. Hopefully, more careful selection of patients, continuous improvement in transport time and the advent of remote ECG transmission from the patient’s home will help to continue reducing treatment delays in transfer patients and in patients presenting outside normal duty hours.

REFERENCES

- 1.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: A quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Widimsky P, Groch L, Zelizko M, Aschermann M, Bednar F, Suryapranata H. Multicentre randomized trial comparing transport to primary angioplasty vs immediate thrombolysis vs combined strategy for patients with acute myocardial infarction presenting to a community hospital without a catheterization laboratory. The PRAGUE Study. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:823–31. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Widimsky P, Budesinsky T, Vorac D, et al. PRAGUE Study Group Investigators Long distance transport for primary angioplasty vs immediate thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. Final results of the randomized national multicentre trial – PRAGUE-2. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:94–104. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen HR, Nielsen TT, Rasmussen K, et al. DANAMI-2 Investigators A comparison of coronary angioplasty with fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalby M, Bouzamondo A, Lechat P, Montalescot G. Transfer for primary angioplasty versus immediate thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis. Circulation. 2003;108:1809–14. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091088.63921.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. American College of Cardiology. American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Canadian Cardiovascular Society ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report ot the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction) Circulation 2004110e82–292. (Errata in 2005;111:2013–4 and 2007;115:e411) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassand JP, Danchin N, Filippatos G, et al. Implementation of reperfusion therapy in acute myocardial infarction. A policy statement from the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2733–41. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong PW, Bogaty P, Buller CE, Dorian P, O’Neill BJ, Canadian Cardiovascular Society Working Group The 2004 ACC/AHA Guidelines: A perspective and adaptation for Canada by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Working Group. Can J Cardiol. 2004;20:1075–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nallamothu BK, Bates ER, Herrin J, Wang Y, Bradley EH, Krumholz HM, NRMI Investigators Times to treatment in transfer patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI)-3/4 analysis. Circulation. 2005;111:761–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155258.44268.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huynh T, O’Loughlin J, Joseph L, et al. AMI-QUEBEC Study Investigators Delays to reperfusion therapy in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Results from the AMI-QUEBEC Study. CMAJ. 2006;175:1527–32. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shavelle DM, Rasouli ML, Frederick P, Gibson CM, French WJ, National Registry of Myocardial Infarction Investigators Outcome in patients transferred for percutaneous coronary intervention (a national registry of myocardial infarction 2/3/4 analysis) Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1227–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nallamothu BK, Bates ER. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction: Is timing (almost) everything? Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:824–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00891-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betriu A, Masotti M. Comparison of mortality rates in acute myocardial infarction treated by percutaneous coronary intervention versus fibrinolysis. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:100–1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinto DS, Kirtane AJ, Nallamothu BK, et al. Hospital delays in reperfusion for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Implications when selecting a reperfusion strategy. Circulation. 2006;114:2019–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.638353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magid DJ, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al. Relationship between time of day, day of week, timeliness of reperfusion, and in-hospital mortality for patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2005;294:803–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.7.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]