Abstract

The Brugada syndrome (BS) is a clinical entity involving cardiac sodium channelopathy, typical electrocardiogram (ECG) changes and predisposition to ventricular arrhythmia. This syndrome is mainly recognized by specialized cardiologists and electrophysiologists. Data regarding BS largely come from multicentre registries or Asian countries. The present report describes the Quebec Heart Institute experience, including the clinical characteristics and prognosis of native French-Canadian subjects with the Brugada-type ECG pattern.

METHODS AND RESULTS:

BS has been diagnosed in 35 patients (mean age 51±12 years) at the Quebec Heart Institute since 2001. Patients were referred from primary care physicians for ECG abnormalities, syncope or ventricular arrhythmia, or were diagnosed incidentally on an ECG obtained for other purposes. The abnormal ECG was recognized after a syncopal spell in four patients and during family screening in four patients. All of the others were incidental findings following a routine ECG. No patient had a family history of sudden cardiac death at younger than 45 years of age. In this population, right bundle branch block pattern with more than 2 mm ST segment elevation in leads V1 to V3 was recorded spontaneously in 25 patients and was induced by sodium blockers in 10 patients. The sodium channel blocker test was performed in 21 patients and was positive in 18 patients (86%). An electrophysiological study was performed in 20 of 35 patients, during which ventricular fibrillation was induced in five patients; three of the five patients were previously asymptomatic. An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was implanted in six of 35 patients (17%), including three of four patients with a history of syncope. A loop recorder was implanted in three patients. After a mean follow-up of 36±18 months, one patient died from a noncardiac cause and one patient (with a history of syncope) received an appropriate shock from his implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. No event occurred in the asymptomatic population.

CONCLUSIONS:

BS is present in the French-Canadian population and is probably under-recognized. Long-term prognosis of individuals with BS, especially in sporadic, asymptomatic cases, needs to be clarified.

Keywords: Arrhythmia, Brugada syndrome, Sudden cardiac death

Abstract

Le syndrome de Brugada (SB) est une entité clinique qui se caractérise par une canalopathie cardiaque, des modifications à l’électrocardiogramme (ECG) classique et une prédisposition à l’arythmie ventriculaire. Ce syndrome est surtout dépisté par des cardiologues spécialisés et des électrophysiologistes. Les données reliées au SB proviennent en grande partie de registres multicentriques ou de pays asiatiques. Le présent rapport décrit l’expérience de l’Institut de cardiologie de Québec, y compris les caractéristiques cliniques et le pronostic de sujets d’origine canadienne française présentant le profil d’EGC type du SB.

MÉTHODOLOGIE ET RÉSULTATS :

Le SB a été diagnostiqué chez 35 patients (âge moyen de 51±12 ans) de l’Institut de cardiologie de Québec depuis 2001. Les patients avaient été aiguillés par des médecins de premier recours en raisons d’anomalies de l’ECG, de syncopes ou d’arythmies ventriculaires, ou ils avaient été diagnostiqués par hasard après un ECG obtenu pour une autre raison. On a constaté l’ECG anormal après une syncope chez quatre patients et pendant un dépistage familial chez quatre patients. Tous les autres sujets ont été dépistés par hasard après un ECG systématique. Aucun patient n’avait d’antécédents familiaux de mort cardiaque subite à moins de 45 ans. Au sein de cette population, on a enregistré un bloc de branche droit spontané avec élévation du segment ST de plus de 2 mm dans les dérivations V1 à V3 chez 25 patients, et induit par des inhibiteurs sodiques chez dix patients. On a procédé au test par inhibiteurs du canal sodique chez 21 patients et obtenu des résultats positifs chez 18 patients (86 %). Vingt des 35 patients ont subi une étude électrophysiologique, au cours de laquelle une fibrillation auriculaire a été induite chez cinq patients, alors que trois des cinq patients étaient asymptomatiques auparavant. On a implanté un défibrillateur à synchronisation automatique à six des 35 patients (17 %), y compris trois des quatre patients ayant des antécédents de syncope. On a implanté un capteur en boucle à trois patients. Après un suivi moyen de 36±18 mois, un patient est mort d’une cause non cardiaque et un autre (ayant des antécédents de syncope) a reçu un choc nécessaire du défibrillateur à synchronisation automatique. Aucun incident ne s’est produit au sein de la population asymptomatique.

CONCLUSIONS :

Le SB existe au sein de la population canadienne française et est probablement sous-dépisté. Il faut élucider le pronostic à long terme des personnes atteintes du SB, notamment les cas asymptomatiques sporadiques.

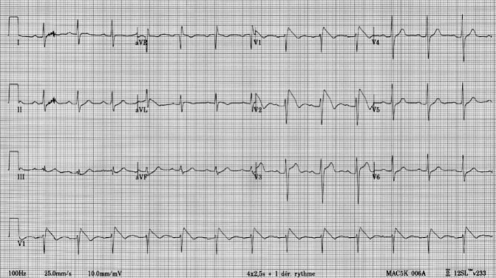

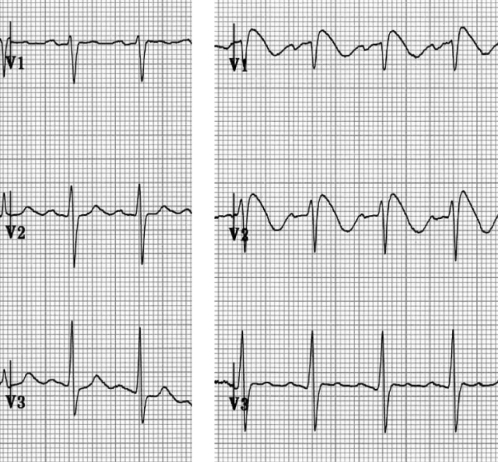

Brugada syndrome (BS) involves a cardiac sodium channel abnormality and is associated with a high risk of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in individuals with a structurally normal heart. BS is mainly recognized in the specialized electrophysiology community. Characteristic electrocardiograms (ECGs) show a typical pattern of a right bundle branch block-like complex and ST segment elevation in leads V1 to V3 (1,2). In a recent consensus statement (3), three types of repolarization patterns were recognized: type 1 is diagnostic of BS and is characterized by an elevated, coved ST segment of 2 mm or greater followed by a negative T wave (Figure 1); type 2 has a saddleback appearance with a high takeoff ST segment elevation of 2 mm or greater followed by an ST elevation of 1 mm or greater and either a positive or a biphasic T wave; and type 3 has either a saddleback or a coved appearance with an ST segment elevation of less than 1 mm. Types 2 and 3 ECGs are not considered diagnostic of BS unless the ST segment elevation converts to a type 1 pattern after administration of a cardiac sodium channel-blocking drug (Figure 2). In a community-based population, the risk of fatal arrhythmic events and the prognostic value of the idiopathic Brugada ECG pattern may be low in asymptomatic subjects without a family history of sudden cardiac death (4–9). Currently, risk stratification is made according to the baseline resting ECG, history of syncope or aborted sudden cardiac death, and ventricular tachyarrhythmia inducibility during programmed ventricular stimulation (10–12). Clinical management with regard to the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of asymptomatic patients has yet to be established (13). The aim of the present study was to assess the clinical characteristics and the prognosis of native French-Canadian subjects with the Brugada-type ECG pattern.

Figure 1).

The type 1 repolarization pattern is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome and is characterized by a coved ST segment of 2 mm or greater followed by a negative T wave

Figure 2).

Pharmacological challenge with intravenous procainamide. A normal electrocardiogram (ECG) pattern (left) converts to a coved-type (type 1) ECG pattern (right)

METHODS

The Quebec Heart Institute in Sainte-Foy, Quebec, is the electrophysiology referral centre for a population of more than 3,000,000 people. Before 2000, no patient with BS had been reported at the Institute. Since 2000, clinical sessions were provided to the local referring cardiologists and internists about BS, with special attention to the ECG manifestations and to the importance of referring all patients with a compatible ECG or clinical findings to a specialized clinic. Between 2001 and 2006, 35 subjects with an ECG compatible with BS were evaluated at the Quebec Heart Institute and comprised the present study population. Patients were included solely if they had a type 1 ECG abnormality at baseline (Figure 1) or at least on one occasion, or after a provocative test using a class 1 antiarrhythmic drug (Figure 2). The diagnosis was established after an episode of aborted cardiac arrest, during the investigation of syncopal episodes of unknown origin, or in asymptomatic patients during routine examination or as a consequence of family screening after the diagnosis of BS was made in a family member. In all patients, the presence of structural heart disease was excluded by clinical history and noninvasive investigations, including echocardiography, stress test and blood chemistry. Invasive tests, including coronary angiography and electrophysiological study (EPS), were performed according to physician or patient preference.

If the typical type 1 ECG pattern was absent at the time of baseline evaluation, a pharmacological challenge with intravenous procainamide (10 mg/kg) was recommended to the patient to unmask Brugada-type abnormalities. During the test, an ECG was recorded with right precordial leads placed in a higher position (second intercostal space) for greater sensitivity. The test was considered positive if a baseline type 2 or 3 or normal ECG pattern converted to a coved-type (type 1) ECG pattern (Figure 2). EPS was then performed using a single-site right ventricular apex stimulation, two basic cycle lengths (600 ms and 400 ms), and induction of one, two and three ventricular premature beats down to a minimum interval of 200 ms. The EPS database was also searched, but no patients with BS were identified.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics

The population comprised 35 subjects (27 men) with a mean age of 51±12 years at diagnosis (range 33 to 83 years). They were all white, native French-Canadian except for one Amerindian. Thirty-one subjects (89%) were asymptomatic, whereas four (11%) had a history of syncope of unknown origin. Asymptomatic individuals were identified during a routine ECG (22 patients), because of a family history of BS (four patients) or because of complaints, such as palpitations (five patients). No patient had a family history of sudden cardiac death at younger than 45 years of age. Acute coronary syndrome was initially suspected before referral in 13 of 35 patients (37%). Of these, three had atypical chest pain and received thrombolytic therapy in the emergency department.

ECG and pharmacological challenge with sodium channel blockers

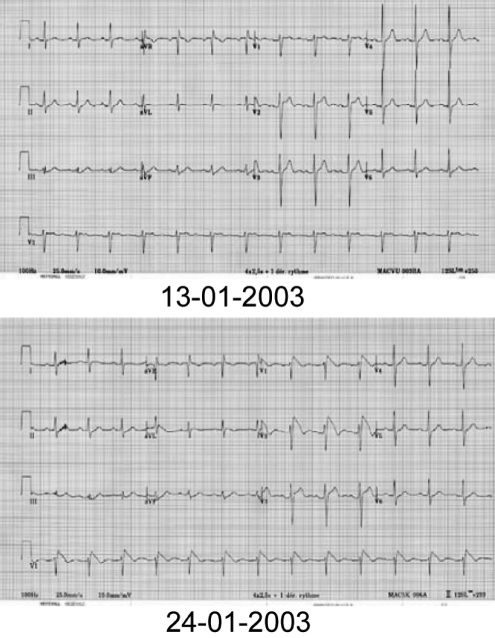

A coved-type (type 1) ECG pattern (Figure 1) in the right pre-cordial leads was recorded spontaneously in 25 patients (71%), after intravenous procainamide infusion in nine patients (Figure 2) and after oral flecainide given for atrial fibrillation in one patient. Over time, all patients showed some ECG fluctuation from a normal ECG pattern to a Brugada type 1 to 3 pattern (Figure 3). Procainamide (10 mg/kg in 10 min to 15 min) was infused intravenously in 21 of 35 patients. The appearance of a diagnostic type 1 ECG pattern was induced in 18 of 21 patients (86%). The test was negative in three patients.

Figure 3).

Electrocardiogram (ECG) fluctuation over time from a normal pattern (top) to a type 1 ECG pattern (bottom)

EPS

EPS was performed in 20 of 35 patients. In the asymptomatic cohort, 16 of 31 patients had EPS, as did all four patients with prior syncope. The mean HV was 47±12 ms. Sustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation was induced in five patients (25%). Three of these five patients were asymptomatic. In contrast, two of 15 noninducible patients had a history of syncope. The four asymptomatic patients with a family history of BS had a negative EPS. In one patient with a history of palpitations, atrioventricular nodal re-entry was induced and slow pathway ablation was performed.

Treatment and clinical follow-up

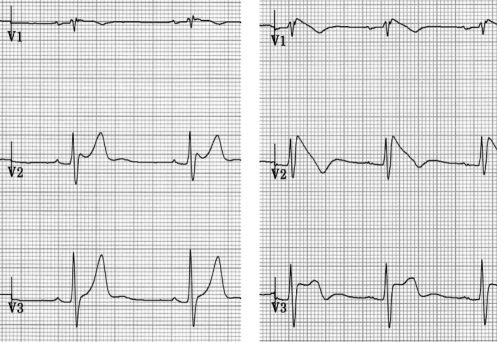

An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was implanted in six of 35 patients (17%). In the four patients with syncope of unknown origin, three received an ICD. In the asymptomatic population, an ICD was implanted in three of 31 patients (10%) based on ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation inducibility. Implantable loop recorder monitors were inserted in three patients: one patient with syncope and a negative EPS (declined ICD) and two patients with palpitations and a negative EPS. No patient with a family history of BS received an ICD. After a mean follow-up of 36±18 months, one patient died from a noncardiac cause (subarachnoidal bleeding). Only one patient had a sustained arrhythmic event. He presented with syncope and had a nondiagnostic type 3 ECG pattern. Intravenous procainamide unmasked the Brugada type 1 ECG pattern (Figure 4). EPS was performed and was negative, but an ICD was implanted. One month after implantation, the patient had two syncopal episodes and the ICD interrogation revealed ventricular fibrillation with appropriate therapy (Figure 5). No inappropriate shock occurred in the patients with ICDs. One patient with a history of syncope who received an implantable loop recorder also had syncope recurrence. The device interrogation revealed no arrhythmia, and the final diagnosis was vasovagal syncope. Two asymptomatic patients with an ICD suffered from depression related to ICD acceptance.

Figure 4).

Left Patient with syncope at presentation and a nondiagnostic type 3 baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) pattern. Right Intravenous procainamide unmasks the Brugada type 1 ECG pattern

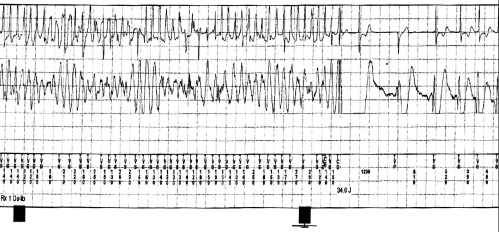

Figure 5).

Recurrence of syncope with an appropriate shock

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the present report is the first to describe the clinical presentation and outcome of native, caucasian Canadians with BS. In our population with BS, no patients had a history of previous cardiac arrest at the time of diagnosis. Sporadic cases without a family history of sudden cardiac death or BS represented 89% (31 of 35 patients) of our cohort. After a mean follow-up of 36±18 months, only one individual (3%) developed aborted sudden death. No asymptomatic patient had an arrhythmic event. This low incidence of arrhythmic events is concordant with other reports (4–8), including the data of Eckardt et al (9) who reported a recurrent arrhythmic event in only 6% (four of 65 patients) of his population with prior syncope and only 0.8% (one of 123 patients) in asymptomatic individuals after a mean follow-up of 40 months. Brugada et al (12) reported on a large number of individuals with a Brugada-like ECG pattern with no previous cardiac arrest or documented ventricular fibrillation. During a mean follow-up of 28 months, 8% (45 of 547 patients) without previous cardiac arrest suffered sudden cardiac death or documented ventricular fibrillation. They also reported that a previous history of syncope and inducibility of ventricular arrhythmias are markers of a poor prognosis in individuals with BS and no previous cardiac arrest (13). In that study (13), a patient with a spontaneously abnormal ECG, a previous history of syncope and inducible, sustained ventricular arrhythmias had a 27.2% probability of suffering an event during follow-up. The low incidence of events in our patients may be explained by a low-risk population overall. The fact that our series of patients were all isolated cases and none had a family history of sudden cardiac death at younger than 45 years of age may suggest spontaneous genetic mutations different from those in other studies.

The number of asymptomatic individuals with a family history of sudden death reported by Brugada et al (10,12,13) was much higher. BS is inherited via an autosomal dominant mode of transmission. The first gene to be linked to BS is SCN5A, the gene encoding for the alpha subunit of the cardiac sodium channel gene (14). Mutations in the SCN5A gene account for approximately 18% to 30% of BS cases. The incidence of SCN5A mutations has been reported to be higher in familial cases than in sporadic cases (15). The different mutations found in BS are characterized by incomplete penetrance, and some probably carry more risk of sudden cardiac death than others. The ultimate answer probably lies in a more comprehensive approach and a more precise understanding of the molecular genetics and their associated electrophysiological abnormalities. Two cases of BS with a heterozygous mutation (R1193Q) polymorphism associated with both long QT syndrome and BS were reported by our group (16). Indeed, a shift of 5 mV of steady-state inactivation to more hyperpolarized voltages observed with R1193Q may explain the typical Brugada-associated ‘loss of function’ of sodium current. Meanwhile, the observation of a residual current also explains the typical ‘gain of function’ of sodium current observed in the long QT syndrome type 3 (16). Interestingly, the R1193Q mutation we found caused both BS and long QT syndrome in one patient, but only BS in the other. It therefore suggests that in addition to the cardiac electrophysiological effect of the R1193Q mutation, other environmental factors are likely to contribute to the clinically observed phenotype, causing either long QT syndrome or BS, or both. These factors have yet to be identified.

According to the second consensus conference report on BS (3), symptomatic patients displaying the type 1 Brugada ECG pattern who present with aborted sudden death or with related symptoms, such as syncope, seizure or nocturnal agonal respiration, should undergo ICD implantation. EPS is recommended in symptomatic patients only for the assessment of supraventricular arrhythmias. In asymptomatic patients, EPS is justified if the type 1 ECG pattern occurs spontaneously or if a family history of sudden cardiac death is present. The decision regarding ICD implantation in patients with syncope, even in the presence of a negative EPS, was appropriate in one of our patients who later received an appropriate therapy for ventricular fibrillation one month after implantation. However, we also observed syncope in one patient with an implantable loop recorder with no documented ventricular arrhythmias. A multicentre study (17) recently reported on a large series of patients with BS implanted with ICDs, and the results were in accordance with the present findings. In the study (17), device interrogation showed no ventricular arrhythmia in 10% of the recurrent syncopal spells. ICD implantation in an asymptomatic population with a positive EPS was based on the report of the second consensus conference on BS (3) and on the Brugada brothers’ studies (10,12,13).

Conflicting data exist on the prognostic role of EPS in BS (9,11,13). One must be aware of the impact and the potential complications of ICD implantation in these young, asymptomatic patients. In the present study, two patients had significant negative psychological effects secondary to ICD implantation. Sacher et al (17) reported a high risk (8.9%/year) of device-related complications (mostly inappropriate shocks) in patients with BS.

CONCLUSIONS

BS is present in the French-Canadian population and is probably under-recognized. Longer follow-up is necessary before conclusions can be drawn on the long-term prognosis of individuals with BS, especially in sporadic, asymptomatic cases.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Quebec Heart Institute, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Quebec, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MT-13181). Dr B Drolet is the recipient of a New Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Dr M Chahine is an Edwards Senior Investigator (Joseph C Edwards Foundation).

REFERENCES

- 1.Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: A distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391–6. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90253-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in leads V1 through V3: A marker for sudden death in patients without demonstrable structural heart disease. Circulation. 1998;97:457–60. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: Report of the second consensus conference: Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association Circulation 2005111659–70. (Erratum in 2005;112:e74) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyasaka Y, Tsuji H, Yamada K, et al. Prevalence and mortality of the Brugada-type electrocardiogram in one city in Japan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:771–4. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuo K, Akahoshi M, Nakashima E, et al. The prevalence, incidence and prognostic value of the Brugada-type electrocardiogram: A population-based study of four decades. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:765–70. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuhashi M, Uno K, Tsuchihashi K, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic ST segment elevation in right precordial leads with right bundle branch block (Brugada-type ST shift) among the general Japanese population. Heart. 2001;86:161–6. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atarashi H, Ogawa S, Harumi K, et al. Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation Investigators Three-year follow-up of patients with right bundle branch block and ST segment elevation in the right precordial leads: Japanese Registry of Brugada Syndrome. Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1916–20. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermida JS, Lemoine JL, Aoun FB, Jarry G, Rey JL, Quiret JC. Prevalence of the Brugada syndrome in an apparently healthy population. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:91–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00835-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckardt L, Probst V, Smits JP, et al. Long-term prognosis of individuals with right precordial ST-segment-elevation Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:257–63. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153267.21278.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brugada J, Brugada R, Antzelevitch C, Towbin J, Nademanee K, Brugada P. Long-term follow-up of individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in precordial leads V1 to V3. Circulation. 2002;105:73–8. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M, et al. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: Insights for risk stratification and management. Circulation. 2002;105:1342–7. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Determinants of sudden cardiac death in individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of Brugada syndrome and no previous cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2003;108:3092–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000104568.13957.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brugada P, Brugada R, Brugada J. Should patients with an asymptomatic Brugada electrocardiogram undergo pharmacological and electrophysiological testing? Circulation. 2005;112:279–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.485326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Q, Kirsch GE, Zhang D, et al. Genetic basis and molecular mechanism for idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Nature. 1998;392:293–6. doi: 10.1038/32675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulze-Bahr E, Eckardt L, Breithardt G, et al. Sodium channel gene (SCN5A) mutations in 44 index patients with Brugada syndrome: Different incidences in familial and sporadic disease Hum Mutat 200321651–2. (Erratum in 2005;26:61) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang H, Zhao J, Barrane FZ, Champagne J, Chahine M. Nav1.5/R1193Q polymorphism is associated with both long QT and Brugada syndromes. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:309–13. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70915-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacher F, Probst V, Iesaka Y, et al. Outcome after implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: A multicenter study. Circulation. 2006;114:2317–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]