Context

ASCO convened an Expert Panel to conduct a systematic review of the literature available through March 2005 to develop guidance to oncologists about available fertility preservation methods and related issues in cancer patients.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are based on the available evidence and address several questions posed by the Panel. Oncologists should address the possibility of infertility with patients treated during their reproductive years. Fertility preservation is often possible, but to preserve the full range of options, fertility preservation approaches should be considered as early as possible during treatment planning.

What Is the Quality of Evidence Supporting Current and Forthcoming Options for Preservation of Fertility in Males?

See Table 1 for a summary of fertility preservation options in male patients.

Table 1.

Summary of Fertility Preservation Options in Males

| Intervention | Definition | Comment | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm cryopreservation (S) after masturbation | Freezing sperm obtained through masturbation | The most established technique for fertility preservation in men; large cohort studies in men with cancer | Outpatient procedure; approximately $1,500 for three samples stored for 3 years; storage fee for additional years* |

| Sperm cryopreservation (S) after alternative methods of sperm collection | Freezing sperm obtained through testicular aspiration or extraction, electroejaculation under sedation, or from a postmasturbation urine sample | Small case series and case reports | Testicular sperm extraction; outpatient surgical procedure |

| Gonadal shielding during radiation therapy (S) | Use of shielding to reduce the dose of radiation delivered to the testicles | Case series | Possible only with selected radiation fields and anatomy; expertise is required to ensure that shielding does not increase dose delivered to the reproductive organs |

| Testicular tissue cryopreservation; testis xenografting; spermatogonial isolation (I) | Freezing testicular tissue or germ cells and reimplantation after cancer treatment or maturation in animals | Has not been tested in humans; successful application in animal models | Outpatient surgical procedure |

| Testicular suppression with GnRH analogs or antagonists (I) | Use of hormonal therapies to protect testicular tissue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy | Studies do not support the effectiveness of this approach |

Abbreviations: S, standard; I, investigational; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

Costs are estimates.

Sperm cryopreservation. Sperm cryopreservation is effective, and oncologists should discuss sperm banking with appropriate patients. It is strongly recommended that sperm are collected prior to initiation of treatment because the quality of the sample and sperm DNA integrity may be compromised even after a single treatment session. Although planned chemotherapy may limit the number of ejaculates, intracytoplasmic sperm injection allows the successful freezing and future use of a very limited amount of sperm.

Hormonal gonadoprotection. Hormonal therapy in men is not successful in preserving fertility when highly sterilizing chemotherapy is administered.

Other considerations. Men should be advised of a potentially higher risk of genetic damage in sperm stored after initiation of therapy. Testicular tissue or spermatogonial cryopreservation and transplantation or testis xenografting have not yet been tested successfully in humans. Of note, such approaches are also the only methods of fertility preservation potentially available to prepubertal boys.

What Is the Quality of Evidence Supporting Current and Forthcoming Options for Preservation of Fertility in Females?

See Table 2 for a summary of fertility preservation options in female patients.

Table 2.

Summary of Fertility Preservation Options in Females

| Intervention | Definition | Comment | Considerations* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryo cryopreservation (S) | Harvesting eggs, IVF and freezing of embryos for later implantation | The most established technique for fertility preservation in women | Requires 10–14 days of ovarian stimulation from the beginning of menstrual cycle Outpatient surgical procedure Requires partner or donor sperm Approximately $8,000 per cycle, $350/year storage fees |

| Oocyte cryopreservation (I) | Harvesting and freezing of unfertilized eggs | Small case series and case reports; as of 2005, 120 live births reported, approximately 1.6% live births per frozen oocyte (3-4 times lower than standard IVF) | Requires 10–14 days of ovarian stimulation from the beginning of menstrual cycle Outpatient surgical procedure Approximately $8,000 per cycle, $350/year storage fees |

| Ovarian cryopreservation and transplantation (I) | Freezing of ovarian tissue and reimplantation after cancer treatment | Case reports; as of 2005, 2 live births reported | Not suitable when risk of ovarian involvement is high Same day outpatient surgical procedure |

| Gonadal shielding during radiation therapy (S) | Use of shielding to reduce the dose of radiation delivered to the reproductive organs | Case series | Possible only with selected radiation fields and anatomy Expertise is required to ensure shielding does not increase dose delivered to the reproductive organs |

| Ovarian transposition (oophoropexy; S) | Surgical repositioning of ovaries away from the radiation field | Large cohort studies and case series suggest approximately 50% chance of success due to altered ovarian blood flow and scattered radiation | Same day outpatient surgical procedure Transposition should be performed just before radiation therapy to prevent return of ovaries to former position May need repositioning or IVF to conceive |

| Trachelectomy (S) | Surgical removal of the cervix while preserving the uterus | Large case series and case reports | Inpatient surgical procedure Limited to early stage cervical cancer; no evidence of higher cancer relapse rate in appropriate candidates Expertise may not be widely available |

| Other conservative gynecologic surgery (S/I) | Minimization of normal tissue resection | Large case series and case reports | Expertise may not be widely available |

| Ovarian suppression with GnRH analogs or antagonists (I) | Use of hormonal therapies to protect ovarian tissue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy | Small randomized studies and case series; larger randomized trials in progress | Medication given before and during treatment with chemotherapy Approximately $500/month |

Abbreviations: S, standard; IVF, in vitro fertilization; I, investigational; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

Costs are estimates.

Embryo cryopreservation. Embryo cryopreservation is considered an established fertility preservation method because it has routinely been used for storing surplus embryos after in vitro fertilization. Approximately 2 weeks of ovarian stimulation with daily injections of follicle-stimulating hormone is required and must be started within the first 3 days of the menstrual cycle.

Cryopreservation of unfertilized oocytes. Cryopreservation of unfertilized oocytes is an option, particularly for patients without a partner or those with religious or ethical objections to embryo freezing. Ovarian stimulation is required as described in the preceding section. Oocyte cryopreservation should be performed only in centers with the necessary expertise, and the Panel recommends participation in institutional review board (IRB) –approved protocols.

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation procedures should be performed only in centers with the necessary expertise under IRB-approved protocols that include follow-up for recurrent cancer. A concern with reimplanting ovarian tissue is the potential for reintroducing cancer cells, although in fewer than 20 procedures reported thus far, there are no reports of cancer recurrence.

Ovarian suppression. Currently, there is insufficient evidence regarding the safety and effectiveness of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and other means of ovarian suppression on fertility preservation. Women interested in this technique are encouraged to participate in clinical trials.

Ovarian transposition. Ovarian transposition (oophoropexy) can be offered when pelvic radiation is administered as cancer treatment. Because of the risk of remigration of the ovaries, this procedure should be performed as close to the radiation treatment as possible.

Conservative gynecologic surgery. It has been suggested that radical trachelectomy be restricted to stage IA2-IB disease with diameter less than 2 cm and invasion less than 10 mm. In the treatment of other gynecologic malignancies, interventions to spare fertility have generally centered on doing less-radical surgery and/or lower-dose chemotherapy with the intent of sparing the reproductive organs as much as possible.

Other considerations. Of special concern in breast and gynecologic malignancies is the possibility that fertility preservation interventions and/or subsequent pregnancy may increase the risk of cancer recurrence. Although several studies have not shown a decrement in survival or an increase in risk of breast cancer recurrence with pregnancy, the studies are all limited by significant biases, and concerns remain for some women and their physicians.

Special Considerations: Fertility Preservation in Children

Use of established methods of fertility preservation (semen cryopreservation and embryo freezing) in postpubertal minor children requires patient assent and parental consent. The modalities available to prepubertal children to preserve their fertility are limited by the sexual immaturity of the children and are essentially experimental. Efforts to preserve fertility of children using experimental methods (e.g., gonadal tissue cryopreservation) should be attempted only under IRB-approved protocols.

What Is the Role of the Oncologist in Advising Patients About Fertility Preservation Options?

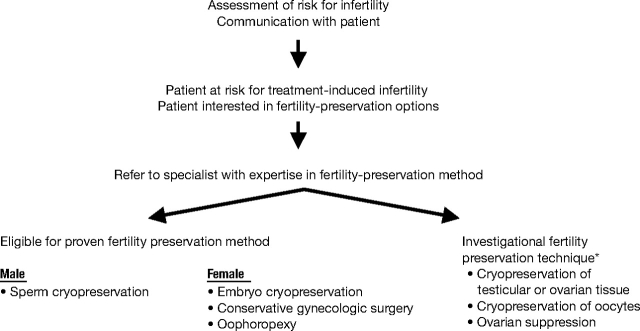

As with other potential complications of cancer treatment, oncologists have a responsibility to inform patients about the risk that their cancer treatment will permanently impair fertility. An algorithm for triaging fertility preservation referrals is presented in Figure 1, and suggested talking points are illustrated in the sidebar.

Figure 1.

Triage of fertility preservation referrals. (*) Clinical trial participation encouraged.

Oncologists should answer basic questions about whether fertility preservation options decrease the chance of successful cancer treatment, increase the risk of maternal or perinatal complications, or compromise the health of offspring. Patients should be encouraged to participate in registries and clinical studies as available to define further the safety of these interventions and strategies. Currently, women with a history of cancer and cancer treatment should be considered high risk for perinatal complications and would be prudent to seek specialized perinatal care.

Oncologists should refer interested and appropriate patients to reproductive specialists as soon as possible. Referral to psychosocial providers may be beneficial when a patient has moderate to severe distress about potential infertility.

Methodology

The literature review found many cohort studies, case series, and case reports, but relatively few randomized or definitive trials examining the success and impact of fertility preservation methods in people with cancer.

Limitations of the Guideline

Fertility preservation methods are still applied relatively infrequently in the cancer population, limiting greater knowledge about success and effects of different potential interventions. Other than risk of tumor recurrence, less attention is paid to the potential negative effects (physical and psychological) of fertility preservation attempts.

Additional Resources

In addition to the full text of the guideline (http://www.asco.org/guidelines/fertility), further resources include a Patient Guide (http://www.plwc.org/patientguides) and a PowerPoint slide set (http://www.asco.org/guidelines/fertility/slides).

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine has both a Mental Health Professional Group (http://www.asrm.org/Professionals/PG-SIG-Affiliated_Soc/MHPG/index.html) and a Fertility Preservation Special Interest Group (http://www.asrm.org/Professionals/PG-SIG-Affiliated_Soc/fpsig/fpsig_index.html).

Cancer patient advocacy organizations such as fertileHOPE (www.fertilehope.org), Lance Armstrong Foundation/LIVESTRONG (www.livestrong.org), and the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (www.komen.org) provide patient information.

Points of Discussion Between the Patient and Physician: Fertility Preservation Methods in Cancer Patients.

Cancer and cancer treatments vary in their likelihood of causing infertility. Individual factors such as disease, age, treatment type and dosages, and pretreatment fertility should be considered in counseling patients about the likelihood of infertility.

Patients who are interested in fertility preservation should consider their options as soon as possible to maximize the likelihood of success. Some female treatments are dependent upon phase of the menstrual cycle and can be initiated only at monthly intervals. Discussion with reproductive specialists and review of available information from patient advocacy resources (e.g., fertileHOPE, the Lance Armstrong Foundation/LIVESTRONG, the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation) can facilitate decision making and treatment planning.

The two methods of fertility preservation with the highest likelihood of success are sperm cryopreservation for males and embryo freezing for females. Conservative surgical approaches and transposition of ovaries or gonadal shielding prior to radiation therapy may also preserve fertility in selected cancers. At this time (2006), other approaches should be considered investigational.

Data are very limited, but there appears to be no detectable increased risk of disease recurrence associated with most fertility preservation methods and pregnancy, even in hormonally sensitive tumors.

Aside from hereditary genetic syndromes and in utero exposure to chemotherapy, there is no evidence that a history of cancer, cancer therapy, or fertility interventions increase the risk of cancer or congenital abnormalities in the progeny.

Treatment-related infertility may be associated with psychosocial distress, and early referral for counseling may be beneficial in moderately distressed people.

It is important to realize that many management questions have not been comprehensively addressed in randomized trials, and guidelines cannot always account for individual variation among patients. A guideline is not intended to supplant physician judgment with respect to particular patients or special clinical situations and cannot be considered inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of other treatments reasonably directed at obtaining the same results.

Accordingly, ASCO considers adherence to this guideline to be voluntary, with the ultimate determination regarding its application to be made by the physician in light of each patient's individual circumstances. In addition, the guideline describes administration of therapies in clinical practice; it cannot be assumed to apply to interventions performed in the context of clinical trials, given that clinical studies are designed to test innovative and novel therapies in a disease and setting for which better therapy is needed. Because guideline development involves a review and synthesis of the latest literature, a practice guideline also serves to identify important questions for further research and those settings in which investigational therapy should be considered.

Footnotes

The Guideline Recommendations on Fertility Preservation in Cancer Patients were developed and written by Stephanie J. Lee (co-chair), MD, MPH, Kutluk Oktay (co-chair), MD, Leslie R. Schover, PhD, Ann H. Partridge, MD, MPH, Pasquale Patrizio, MD, MBE, W. Hamish Wallace, MD, Karen L. Hagerty, MD, Lindsay N. Beck, and Lawrence V. Brennan, MD.