Abstract

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae NTE1 gene encodes an evolutionarily conserved phospholipase B localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that degrades phosphatidylcholine (PC) generating glycerophosphocholine and free fatty acids. We show here that the activity of NTE1-encoded phospholipase B (Nte1p) prevents the attenuation of transcription of genes encoding enzymes involved in phospholipid synthesis in response to increased rates of PC synthesis by affecting the nuclear localization of the transcriptional repressor Opi1p. Nte1p activity becomes necessary for cells growing in inositol-free media under conditions of high rates of PC synthesis elicited by the presence of choline at 37 °C. The specific choline transporter encoded by the HNM1 gene is necessary for the burst of PC synthesis observed at 37 °C as follows: (i) Nte1p is dispensable in an hnm1Δ strain under these conditions, and (ii) there is a 3-fold increase in the rate of choline transport via the Hnm1p choline transporter upon a shift to 37 °C. Overexpression of NTE1 alleviated the inositol auxotrophy of a plethora of mutants, including scs2Δ, scs3Δ, ire1Δ, and hac1Δ among others. Overexpression of NTE1 sustained phospholipid synthesis gene transcription under conditions that normally repress transcription. This effect was also observed in a strain defective in the activation of free fatty acids for phosphatidic acid synthesis. No changes in the levels of phosphatidic acid were detected under conditions of altered expression of NTE1. Consistent with a synthetic impairment between challenged ER function and inositol deprivation, increased expression of NTE1 improved the growth of cells exposed to tunicamycin in the absence of inositol. We describe a new role for Nte1p toward membrane homeostasis regulating phospholipid synthesis gene transcription. We propose that Nte1p activity, by controlling PC abundance at the ER, affects lateral membrane packing and that this parameter, in turn, impacts the repressing transcriptional activity of Opi1p, the main regulator of phospholipid synthesis gene transcription.

Introduction

Neuropathy target esterase (NTE1) encodes a phosphatidylcholine (PC)3-specific phospholipase B conserved from yeast to man. The Nte1p enzyme catalyzes the deacylation of PC in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resulting in the production of glycerophosphocholine and two molecules of free fatty acid (1, 2) (Fig. 1). In adult animals, the NTE1-encoded protein is enriched in the brain and was originally described as neuropathy target esterase as its activity is inhibited by organophosphates found in pesticides resulting in chronic neuropathy (3, 4). Mutations in the human NTE1 gene cause an autosomal recessive motor neuron disease (5). Homozygous null mice for NTE1−/− die at embryonic day 9 (6). NTE1+/− heterozygote mice exposed to organophosphates displayed increased levels of hyperactivity compared with wild type animals consistent with a role in regulation of motor activity (7), whereas neuron-specific inactivation of NTE1 leads to cellular pathology in the hippocampus, thalamus, and cerebellum (8–10). The NTE1 gene of Drosophila (known as swiss cheese) is not essential for life with homozygous null swiss cheese−/− flies displaying age-dependent neurodegeneration (9, 10). Impairment of Nte1p-mediated PC turnover causes abnormal cellular and tissue development in the placenta and central nervous system characterized at the cellular level by intracytoplasmic vacuolation, abnormal ER structures, and multilayered membrane stacks (6, 8–10).

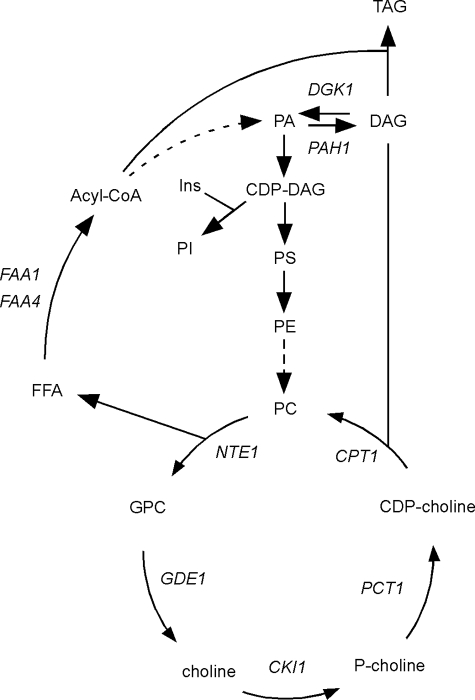

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of phospholipid pathways connected to the phospholipase B Nte1p. PC, synthesized either by sequential methylation of PE or by condensation of DAG with CDP-choline, is degraded by Nte1p producing glycerophosphocholine (GPC) and free fatty acids (FFA). Glycerophosphocholine can be recycled back into choline for PC synthesis. Free fatty acid is activated to acyl-CoA for PA synthesis or triacylglycerol synthesis. Solid arrows indicate direct enzymatic conversions. Dashed arrows indicate conversions that require more than one enzymatic step. Relevant genes mentioned in the text encoding enzymes responsible for catalyzing some of these steps are indicated. Ins, inositol; TAG, triacylglycerol.

PC can be turned over via several different lipases beyond the phospholipase B activity encoded by NTE1. These lipases produce numerous second messengers, including arachidonic acid for the synthesis of prostaglandins and leukotrienes to control inflammatory and immune responses, lysophosphatidylcholine to provide a chemotactic signal for macrophages and lymphocytes, and diacylglycerol for the activation of protein kinases (11–14). Although it is known that the NTE1-encoded phospholipase B catalyzes the deacylation of PC to produce fatty acids and glycerophosphocholine, its cellular role is not known. We studied Nte1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to further our understanding of its cellular function.

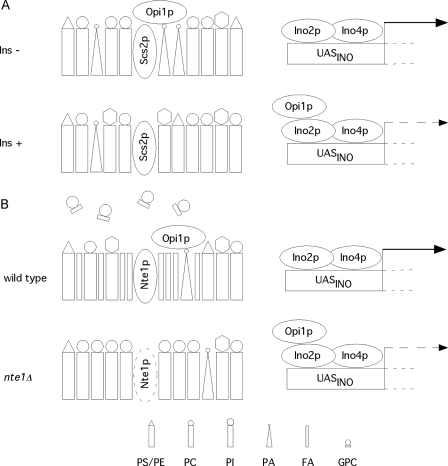

Phospholipid metabolism in S. cerevisiae is regulated transcriptionally by a complex network of signals that converge at two transcriptional activators, Ino2p and Ino4p, and a transcriptional repressor, Opi1p (Fig. 9A) (15–18). Opi1p is the main tuning component of this regulatory system. Ino2p and Ino4p form a heterodimer that binds to an upstream-activating sequence (UASINO) present in the promoters of genes involved in phospholipid biosynthesis and promotes their transcription. Interaction of Opi1p with Ino2p represses transcription of UASINO-containing genes. The most highly regulated gene by this circuit is INO1. INO1 encodes inositol-3-phosphate synthase responsible for the conversion of glucose 6-phosphate to inositol 3-phosphate, the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of phosphatidylinositol (PI). Under inositol-deplete conditions, the INO1 gene is highly transcribed, and upon inositol supplementation, transcription of INO1 is attenuated by the activity of Opi1p. Opi1p regulation of transcription of other phospholipid biosynthetic genes containing UASINO in their promoters takes place in a similar manner to that of INO1, although the rate of repression varies among them (15–18).

FIGURE 9.

Transcriptional repressor Opi1p regulates phospholipid synthesis gene expression in response to lipid precursor phosphatidic acid abundance and to lateral membrane packing. A depicts the current model of phospholipid synthesis gene transcriptional regulation whereby Opi1p binds to membranes in response to increased levels of PA. Recruitment of Opi1p to ER/nuclear membrane allows for transcription of UASINO-containing genes. Opi1p regains repressing activity upon a drop in PA level. B depicts the role proposed for Nte1p enhancing phospholipid synthesis gene transcription by affecting membrane tension. For cells growing without exogenous inositol, there is an increase in Nte1p-mediated PC degradation revealed by glycerophosphocholine accumulation. Nte1p becomes necessary when higher rates of PC synthesis are triggered by choline supplementation at 37 °C. Nte1p phospholipase B activity antagonizes increasing PC abundance and controls lateral membrane packing promoting Opi1p binding and consequent phospholipid synthesis gene transcription. Through these two concerted effects (PC degradation and enhancing phospholipid synthesis), Nte1p generates and maintains phospholipid heterogeneity.

It was recently demonstrated that Opi1p is of the class of transcription factors that exist as inactive membrane-bound forms that need to be released from membranes to regulate transcription (19). This is an emerging theme among transcription factors that regulate membrane lipid composition and includes the sterol regulatory element-binding proteins that normalize transcription of cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis genes (20) and Mga2p and Spt23p that control transcription of the sole fatty acid desaturase encoding gene OLE1 in S. cerevisiae (21). Opi1p has been demonstrated to bind phosphatidic acid (PA) and the integral ER resident protein Scs2p (VAMP-associated protein) (19, 22, 23). A decrease in PA levels results in the release of Opi1p from membranes promoting its transit to the nucleoplasm where Opi1p interacts with Ino2p and attenuates transcription of UASINO-containing genes (Fig. 9A). Inositol addition is thought to elicit such a response by increasing the rate of PI synthesis resulting in a drop in PA levels due to a requirement for CDP-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG) production to support the synthesis of PI (19, 24). The addition of choline to the medium exacerbates the repression by Opi1p but has no effect on its own.

PA plays a pivotal role in phospholipid metabolism. In addition to its role through Opi1p for transcriptional regulation of phospholipid synthesis, PA is the central precursor for phospholipid synthesis (Fig. 1). Flux alterations through the different phospholipid pathways induce changes in PA levels that in turn affect transcriptional regulation of UASINO-containing genes (16, 24). The recent characterization of the PAH1-encoded PA phosphatase and the DGK1-encoded DAG kinase revealed the role of a PA pool associated with the ER/nuclear compartment in gene transcription regulation and nuclear membrane proliferation (25–30). Interestingly, PAH1-encoded PA phosphatase was found associated with the promoters of several UASINO-containing genes in a phosphorylation-dependent manner and was shown to act as a repressor on those genes independent of Opi1p (25, 26).

Compelling evidence demonstrates the influence of PC metabolism on transcriptional regulation of UASINO-containing genes. Yeast strains bearing hypomorphic alleles of genes responsible for the synthesis of phospholipids through the CDP-DAG branch exhibit a conditional overproduction of inositol phenotype that arises from deregulated transcription of the INO1 gene (16, 17). This overproduction of inositol phenotype is conditional as it is alleviated when higher rates of PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway are produced by choline supplementation. Low flux through the CDP-DAG branch for PC synthesis provokes a build up of PA, preventing Opi1p regulation of UASINO-containing genes, whereas restoration of PC synthesis by the addition of exogenous choline drags upon the PA pool through DAG consumption and reestablishes normal Opi1p-mediated transcriptional regulation.

In addition to PA, Opi1p interacts with the ER resident protein Scs2p. A yeast strain with an inactivated SCS2 gene is an inositol auxotroph (Ino−) due to Opi1p losing one of its membrane anchors resulting in the release of Opi1p into the nucleoplasm where it is free to interact with Ino2p and represses INO1 transcription. Consistent with the notion that alterations in PC metabolism impact phospholipid gene transcription is the observation that blocking PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway alleviates the Ino− phenotype of scs2 mutants (24, 31).

In this study, we demonstrate that Nte1p-mediated PC turnover sustains phospholipid synthesis gene transcription and describe a role for Nte1p generating and maintaining phospholipid heterogeneity. We show that Nte1p impacts on UASINO-containing gene transcription regulation independently of overall PA levels, and we propose that Opi1p is sensitive to alterations in lateral membrane packing at the ER produced by Nte1p enzymatic activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

[methyl-14C]Choline chloride, [methyl-3H]methionine, and carrier-free [32P]H3PO4 were from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. [α-32P]dCTP was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Antibodies used were anti-hemagglutinin (HA), anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-linked IgG, anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-linked IgG (Cell Signaling), anti-TAP (Open Biosystems), and anti-Pgk1 (Molecular Probes). Agar was from Sigma. Growth media were from Difco. Tunicamycin was from Calbiochem.

Media and Culture Conditions

Yeast cells were maintained in YEPD medium (1% bacto-yeast extract, 2% bacto-peptone, 2% dextrose) or SD medium (0.67% bacto-yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2% dextrose) supplemented as required for plasmid maintenance and nutrient auxotrophies. Chemically defined synthetic complete medium, which does not contain inositol, was prepared as described previously (32). Yeast cells were routinely grown at 25 °C.

Yeast Strains and Plasmids

The yeast strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. Single deletion mutants in the BY4741 background were obtained from Euroscarf. The genetic KanMX6 marker of the nte1Δ strain was replaced with the nourseothricin acetyltransferase gene cassette using plasmid pAG25 (33) as described previously (34). Nourseothricin-resistant colonies were analyzed by PCR to verify the integration of the drug-resistant cassette into the NTE1 locus. One isolate was backcrossed with strain BY4742. Upon random sporulation, a single nte1Δ colony bearing the otherwise BY4741 genotype was selected and used throughout this study. The INO1 gene was chromosomally tagged to generate a C-terminal 3×HA fusion protein product by a PCR-mediated procedure using plasmid pFA6a-3HA-His3MX6 as a template and primers INO1-F2 and INO1-R1 (35). Genetic markers were swapped according to Voth et al. (34). Double mutant strains were constructed by standard genetic crosses and sporulation. The catalytically dead allele of NTE1 was generated by single T to G transversion of base 4216 of the open reading frame substituting the serine at residue 1406 to alanine using the QuickChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mutagenesis was verified by sequencing and the phenotype confirmed by pulse-chase analysis of PC turnover. The INO1 gene was amplified by PCR using the primers indicated in Table 2 and verified by DNA sequencing. Plasmids synthesized and used in this study are indicated in Table 3.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| BY4741 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 met15Δ0 | Euroscarf |

| PMY297 | BY4741 nte1Δ::NatMX6 | This study |

| PMY427 | BY4741 nte1ΔNatMX6 cki1Δ::KanMX6 | This study |

| PMY290 | BY4741 nte1ΔNatMX6 pct1Δ::KanMX6 | This study |

| PMY431 | BY4741 nte1ΔNatMX6 cpt1Δ::KanMX6 | This study |

| PMY568 | BY4741 INO1-HA::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| PMY617 | BY4741 INO1-HA::HIS3MX6 nte1Δ::NatMX6 | This study |

| PMY614 | BY4741 INO1-HA::HIS3MX6 scs2Δ::KanMX6 | This study |

| PMY613 | BY4741 INO1-HA::HIS3MX6 scs3Δ::KanMX6 | This study |

| PMY327 | BY4741 faa1Δ::HygMX6 | This study |

| PMY459 | BY4741 faa1Δ::HygMX6 faa4Δ::KanMX6 | This study |

| PMY603 | BY4741 INO1-HA::HIS3MX6 faa1Δ::HygMX6 faa4Δ::KanMX6 | This study |

| PMY437 | BY4741 nte1Δ::NatMX6 opi1Δ::KanMX6 | This study |

| PMY621 | BY4741 ino80Δ::HIS3 | 60 |

| PMY593 | BY4741 OPI1-GFP::HIS3MX6 | Invitrogen |

| PMY719 | BY4741 OPI1-GFP::HIS3MX6 nte1Δ::NatMX6 | This study |

| PMY717 | BY4741 OPI1-GFP::HIS3MX6 nte1Δ::NatMX6 pct1Δ::KanMX6 | This study |

| GGY023 | BY4741 HNM1-TAP::HIS3MX6 | Open Biosystems |

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer designation | Primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| INO1-F2 | GGATTGCCTTCTCAAAACGAACTAAGATTCGAAGAGAGATTGTTGCGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA |

| INO1-R1 | TTTATAGGTAGGCGGAAAAAGAAAAAGAGAGTCGTTGAAATGAGAGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC |

| F-INO1-SacII | TCCGCGGTGCCCTTGATGGACAACAAAC |

| R-INO1-KpnI | TGGTACCAACTTCACTGGGCCTTGTTGAG |

| F-NTE1-S1406A | CGTTATTGGAGGAACAGCGATTGGTTCC |

| R-NTE1-S1406A | GGAACCAATCGCTGTTCCTCCAATAACG |

TABLE 3.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Source or Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| pRS426-NTE1 | NTE1 subcloned into a 2-μm URA3 plasmid | 2 |

| pRS426-NTE1 S1406A | NTE1 with the following mutation, S1406A, subcloned into a 2-μm URA3 plasmid | This study |

| pRS416-INO1 | INO1 subcloned into a CEN URA3 plasmid | This study |

| pRS426-INO1 | INO1 subcloned into a 2-μm URA3 plasmid | This study |

| pFA6a-3HA-His3MX6 | Hemagglutinin epitope tagging cassette | 35 |

| PAG25 | NatMX4 gene cassette | 33 |

| pJH310-INO1 | INO1 gene for riboprobe | S. Henry |

| pSJ34-ACT1 | ACT1 gene for riboprobe | S. Henry |

| pJH359-LEU | PINO1-LacZ; LEU2 | S. Henry |

| pAB709 | PCHO1-LacZ; URA3 | G. Carman |

Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

Logarithmically growing cells from a 5-ml culture (A600 of 0.5) were harvested, washed, and taken up in 200 μl of 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, 20% glycerol containing Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) plus 1 μg/ml pepstatin A. Cells were broken with glass beads using a bead beater for two periods of 1 min intercalated with 1 min on ice. Cell debris was removed by 3 min of centrifugation at 500 × g, and supernatants were saved. Proteins were fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and detected using appropriate primary and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies followed by enhanced chemiluminescence.

RNA Isolation and Northern Blot Analysis

Total RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis were performed as described previously (36). Membranes were probed in formamide hybridization buffer with strand-specific 32P-labeled riboprobes, obtained from linearized plasmids pJH310-INO1 and pSJ34-ACT1 by in vitro transcription.

β-Galactosidase Assays

β-Galactosidase activity was measured by following spectrophotometrically the formation of O-nitrophenol from O-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside. Yeast cell extracts were prepared in 100 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 10 mm KCl, and 1 mm MgSO4 containing EDTA-free Complete protease inhibitor mixture plus 1 μg/ml pepstatin A. Enzyme assays were conducted at room temperature in 1 ml of the same phosphate buffer containing 2.2 mm O-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside and appropriate aliquots of cell extracts (2.5–40 μg of protein). Alternatively, a yeast β-galactosidase assay kit (Pierce) was used following manufacturer's instructions. The assays were conducted in quadruplicate and under linear conditions for time and protein concentration. One enzyme unit catalyzes the formation of 1 μmol of product per min.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Yeast cells were grown to mid-log phase at 25 °C in synthetic medium lacking inositol and transfer at 37 °C, and after 30 min 2 mm choline was added. Aliquots (0.5 ml) were withdrawn, after an additional hour, cells were spun down at 500 × g for 3 min and resuspended in a small amount of the same warm media. Cells were mounted on slides kept at 37 °C on a heating block until microscopy was performed as described previously (37). Live cells were observed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M microscope fitted with a plan-neofluor 100× oil immersion lens. Images were captured using a Zeiss AxioCam HR using Axiovision 4.5 software.

[methyl-3H]Methionine Labeling

Yeast cells were incubated with [methyl-3H]methionine for at least seven generations for steady state labeling of metabolites derived from the phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) methylation pathway. Analyses of radioactivity distribution in aqueous and organic cellular fractions were performed as described previously (2). Most, if not all, of the radioactivity associated with the aqueous fraction was distributed among choline, phosphocholine, glycerophosphocholine, and methionine.

Choline Transport Assays

Cells were grown to mid-log phase in choline-containing media at 25 or 37 °C. Cell were harvested, thoroughly washed three times with choline-free fresh medium, and resuspended in identical medium containing 10 μm (100,000 dpm/nmol) [14C]choline. Choline uptake rates were determined as described previously (2).

RESULTS

Nte1p-mediated PC Degradation Is Required for Inositol Prototrophy under High Rates of PC Synthesis through the CDP-choline Pathway

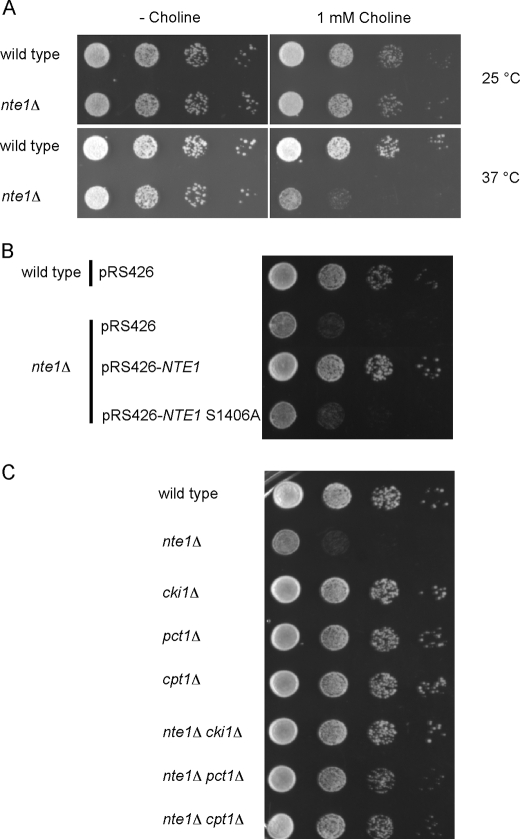

In the course of our studies on the cellular function of Nte1p and its participation in lipid metabolism, we observed that cells containing an inactivated NTE1 gene (nte1Δ) grew poorly in the absence of inositol under growth conditions promoting high rates of PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway at 37 °C supplemented with choline (Fig. 2A). Transformation of nte1Δ cells with a wild type allele of the NTE1 gene, borne on a low copy or high copy vector, restored inositol prototrophy, whereas the introduction of a mutant allele coding for a catalytically dead variant of Nte1p where the active site serine residue was changed to alanine did not alleviate the Ino− phenotype of nte1Δ cells (Fig. 2B). With exogenous inositol concentrations above 10 μm, nte1Δ cells grew like wild type at any temperature (data not shown). This implies that it is the metabolism of PC to glycerophosphocholine and free fatty acids by Nte1p that is required to prevent the Ino− phenotype.

FIGURE 2.

High rates of PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway elicit an inositol auxotrophy in the absence of Nte1p phospholipase B activity. Cells of the indicated genotypes were grown to mid-log phase in synthetic media containing 5 μm inositol at 25 °C. Cell suspensions were spotted as 10-fold serial dilutions at an initial cell density of A600 of 0.4 onto agar plates. A, cells were spotted onto inositol-free synthetic media with or without 1 mm choline and incubated at 25 or 37 °C for 2 days. B and C, cell were spotted in inositol-free media and grown for 2 days at 37 °C.

When yeast cells growing in choline-containing media are shifted to 37 °C, there is an increase in the rate of PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway, and this is balanced by a concomitant increase in PC catabolism mediated by Nte1p (Fig. 1) (1, 2, 38). We surmised that the enhanced growth defect in the absence of inositol observed in nte1Δ cells when shifted to 37 °C could be related to unbalanced PC metabolism. Increased PC synthesis was not being counterbalanced by increased PC degradation. This was the case as blocking the synthesis of PC by inactivating any of the three genes coding for the enzymes of the CDP-choline pathway alleviated the Ino− phenotype of nte1Δ cells at any temperature (Fig. 2C). Inactivation of the HNM1 gene encoding the choline transporter also prevented the inositol auxotrophy of nte1Δ cells (data not shown) consistent with the dependence of the Ino− phenotype of nte1Δ cells on exogenous choline. Taken together, the results show that the Ino− phenotype of nte1Δ cells is due to active PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway and that alternate routes of PC degradation cannot substitute for the function provided by Nte1p.

Inositol Auxotrophy of nte1Δ Cells Is Due to a Defect in Transcriptional Regulation of the INO1 Gene

The most common cause of the Ino− phenotype is improper regulation of transcription of the INO1 gene leading to reduced levels of its protein product Ino1p, an inositol-3-phosphate synthase that converts glucose 6-phosphate to inositol 3-phosphate and is the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of PI. As a consequence, the decrease in Ino1p level reduces the rate of inositol synthesis in turn imposing a restriction on cell growth because of decreased PI synthesis.

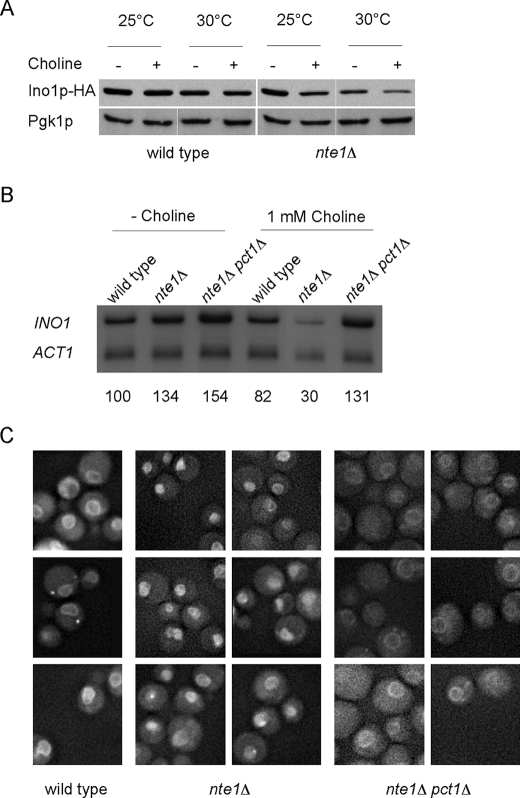

To directly analyze the level of Ino1p, the genomic version of the INO1 gene was tagged with a 3×HA epitope fused to the C terminus of the encoded protein of the open reading frame. The presence of the 3×HA epitope did not prevent the enzymatic activity of Ino1p at 25 or 30 °C as revealed by the inositol prototrophic character of the strain bearing the 3×HA-tagged allele of INO1 at those temperatures (data not shown). Congruently, Western blot analysis for the HA epitope from whole cell extracts obtained from yeast grown at 25 or 30 °C in low (5 μm) inositol revealed similar levels of expression at both temperatures (Fig. 3A). Analyses performed on extracts obtained from cells grown in inositol-replete (75 μm) medium at both temperatures showed undetectable levels of Ino1p indicating that the regulatory elements of the INO1 gene were not affected as a consequence of the 3×HA tag (data not shown). However, the strain exhibited an Ino− phenotype at 37 °C and very low levels of Ino1p protein revealed by Western blot analysis from cell extracts grown at 37 °C in 5 μm inositol (data not shown). This suggests that the presence of the 3×HA tag at the C terminus destabilizes the Ino1p protein at 37 °C promoting its degradation and provoking the Ino− phenotype. The Ino1p-3×HA chimera is a reliable monitor of changes in Ino1p level at 25 and 30 °C, but its instability at 37 °C precluded its use at this temperature.

FIGURE 3.

Ino− phenotype of nte1Δ cells reflects decreased levels of INO1 gene mRNA and Ino1p protein and correlates with Opi1p nucleoplasmic localization. A, wild type and nte1Δ cells carrying an HA-tagged allele of INO1 were grown in synthetic medium containing 5 μm inositol with or without the addition of 1 mm choline at the indicated temperatures. Whole cell extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis using a mouse anti-HA monoclonal antibody (upper panel) and reprobed with a mouse anti-Pgk1p monoclonal antibody (lower panel) as load control. B, wild type, nte1Δ, and nte1Δ pct1Δ were grown in synthetic medium containing 5 μm inositol with or without the addition of 1 mm choline at 37 °C. RNA was extracted and subjected to Northern blot analysis for INO1 and ACT1 mRNAs. The amount of INO1 transcript detected for each sample is indicated relative to that of wild type cells growing without choline after standardization for ACT1 mRNA content. C, wild type, nte1Δ, and nte1Δ pct1Δ cells expressing Opi1p-GFP from its own promoter were grown to mid-log phase in synthetic medium lacking inositol. Cells were shifted at 37 °C and 2 mm choline was added after 30 min. Live cells were visualized through Zeiss green fluorescent protein filters after an additional hour at 37 °C.

Taking into account our observation that the presence of choline was required to elicit the Ino− phenotype of nte1Δ cells, we analyzed by Western blot the effect of choline supplementation on the level of Ino1p in wild type and nte1Δ cells grown in low inositol (5 μm) liquid medium. The addition of 1 mm choline did not affect the level of Ino1p in wild type cells, whereas a modest diminution of Ino1p was observed for nte1Δ cells grown at 25 °C with a more pronounced reduction detected at 30 °C (Fig. 3A).

Northern blot analysis showed that the Ino− phenotype of nte1Δ cells arises from reduced levels of INO1 gene mRNA when high rates of PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway are sustained. The abundance of INO1 mRNA was restored to normal levels in nte1Δ cells when choline was omitted from the growth media or when the synthesis of PC through the CDP-choline pathway was blocked by inactivation of the PCT1 gene (Fig. 3B). Under conditions of increased flux through the CDP-choline pathway, via supplementation with exogenous choline and increasing growth temperature, the absence of Nte1p phospholipase B activity leads to improper regulation of the INO1 gene resulting in decreased levels of Ino1p and inositol auxotrophy.

The CHO1 gene encodes phosphatidylserine synthase, and like the INO1 gene is under the transcriptional control of Ino2p, Ino4p, and Opi1p, as UASINO elements are present in its promoter (39). Analogous to the changes observed in INO1 mRNA levels, using a β-galactosidase reporter assay, we detected a 45% decrease in transcriptional activity of the CHO1 promoter in nte1Δ cells undergoing high rates of PC synthesis when compared with wild type cells under the same conditions. Paralleling the observations on INO1 gene regulation, preventing PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway restored the transcriptional activity driven from the CHO1 promoter to wild type values (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Transcriptional activity of the CHO1 promoter under high rates of PC synthesis

Yeast cells of the indicated genotypes bearing the lacZ gene under control of the CHO1 promoter on a URA3 plasmid were grown to mid-log phase in synthetic selective media containing 5 μm inositol and 1 mm choline at 37 °C. Cells were processed for β-galactosidase activity.

| Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity |

|---|---|

| units/mg | |

| Wild type | 6.4 ± 0.3 |

| nte1Δ | 3.6 ± 0.37 |

| nte1Δ pct1Δ | 8.0 ± 1.7 |

We investigated if the repressed status of UASINO-containing genes induced upon increased rates of PC synthesis in the absence of Nte1p phospholipase B activity correlates to changes in Opi1p localization. Strains were built bearing a chromosomally tagged OPI1 gene expressing a C-terminal green fluorescent protein fusion that was fully functional. Opi1p-GFP was visualized in the nucleoplasm for most nte1Δ cells (Fig. 3C), whereas for wild type cells and for nte1Δ pct1Δ cells, Opi1p-GFP was localized to the perinuclear membrane.

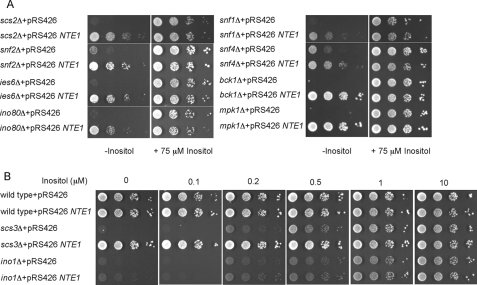

Overexpression of NTE1 Promotes INO1 Gene Expression

Because Nte1p phospholipase B activity is required for sustained expression of phospholipid synthesis genes under high rates of PC synthesis, we examined the converse by determining the effect of overexpressing NTE1 on the expression levels of UASINO-containing genes. It was reported recently that the overexpression of NTE1 alleviated the Ino− phenotype of the cell wall integrity (CWI) pathway mutant mpk1Δ (40). We confirmed this observation and extended it to bck1Δ, another mutant of the same pathway (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Increased expression of NTE1 alleviates the Ino−phenotype of most Ino−mutants. A and B, cells of the indicated genotypes were transformed with a high copy plasmid bearing a wild type allele of NTE1 or an empty vector. Transformed cells were grown in synthetic selective medium containing 10 μm inositol at 25 °C. Cell suspensions were spotted as a 10-fold serial dilutions at an initial cell density of A600 of 0.4 onto synthetic selective medium containing the indicated amount of inositol and grown for 2 days at 37 °C.

Overexpression of NTE1 alleviated the Ino− phenotype of all inositol auxotroph mutants tested with the exception of those encoding proteins directly required to transcribe INO1-ino2Δ, ino4Δ, and the ino1Δ strain itself (Fig. 4, A and B, and Fig. 6). The overexpression of NTE1 in an ino1Δ strain did not confer any growth advantage compared with its control when assessed on plates containing limiting inositol concentrations (from 0 to 10 μm; Fig. 4B) indicating that the restoration of growth on inositol-free media mediated by NTE1 depends on the presence of a functional INO1 gene.

FIGURE 6.

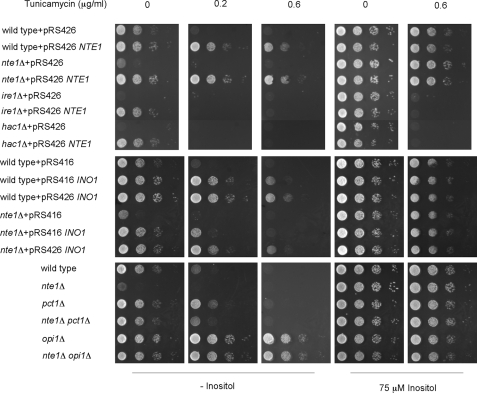

Alterations on PC metabolism impact on the establishment of the UPR by affecting inositol-derived metabolism. Cells of the indicated genotypes were grown in appropriate synthetic selective media containing 10 μm inositol to the exponential phase of growth at 25 °C. Cell suspensions were spotted as 10-fold serial dilutions at an initial cell density of A600 of 0.4 onto synthetic medium containing the indicated amount of tunicamycin and inositol. Plates were incubated 2 days at 37 °C.

Mutant strains with defective SWI/SNF (snf2Δ) or INO80 (ino80Δ, ies6Δ) function, both complexes involved in chromatin remodeling at the INO1 promoter (41–44), were no longer inositol auxotrophs when NTE1 was overexpressed. Similarly, the inositol auxotrophy of mutants defective in the protein kinase complex Snf1p-Snf4p (45), and mutants unable to mount the unfolded protein response (UPR) (46, 47), was alleviated when NTE1 was overexpressed (Fig. 4A and Fig. 6, respectively).

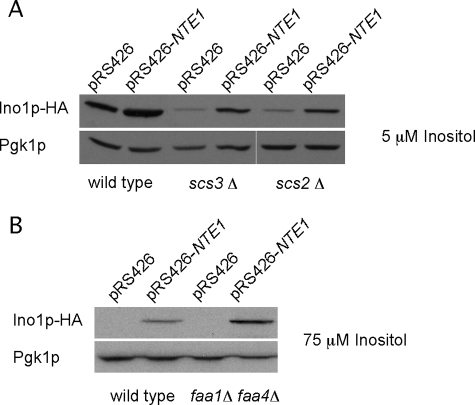

The SCS3 gene was first identified as required for inositol prototrophy in the presence of choline, and it was reported that its inactivation triggered neither a reduction in the level of INO1 mRNA nor a decrease in the enzymatic activity of Ino1p (48). Recently, it was characterized as the yeast orthologue of a conserved gene family involved in lipid droplet formation (49). As for many other inositol auxotroph mutants analyzed here, the overexpression of NTE1 allowed scs3Δ cells to grow in the absence of exogenous inositol (Fig. 4B). Western blot analysis revealed that the amount of Ino1p was lower in scs3Δ cells compared with wild type cells, whereas its level was considerably augmented when NTE1 was overexpressed (Fig. 5A), indicating that the restoration of inositol prototrophy for scs3Δ cells mediated by NTE1 results from increased levels of Ino1p. We cannot currently address the inconsistencies between our results and those that previously reported no changes in INO1 mRNA abundance and in Ino1p enzyme activity for scs3Δ cells (48). Further studies are necessary to solve this apparent contradiction.

FIGURE 5.

NTE1 overexpression promotes increased levels of Ino1p under repressing and nonrepressing conditions. A and B, cells of the indicated genotypes bearing an HA-tagged allele of INO1 were transformed with a high copy plasmid bearing a wild type allele of NTE1 or an empty vector. Transformed cells were grown in synthetic selective medium containing the indicated amount of inositol at 25 °C. Whole cell extracts were prepared, and 5 μg of protein (A) or 40 μg of protein (B) were subjected to immunoblot analysis using a mouse anti-HA monoclonal antibody and reprobed with a mouse anti-Pgk1p monoclonal antibody as load control.

Scs2p plays an important role in Opi1p function regulation. Opi1p interacts with Scs2p through two phenylalanines in an acidic tract (FFAT) motif and together with PA constitutes the known ER anchors for Opi1p that prevent Opi1p nucleoplasm localization and gene repression (19, 23). Point mutations in the FFAT motif of Opi1p or in the corresponding Opi1p binding region of Scs2p reduce the affinity of this interaction and elicit an Ino− phenotype (23, 50, 51), as does inactivation of the SCS2 gene (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the Ino− phenotype of scs2Δ cells was also alleviated by overexpressing NTE1. SCS22 is a homologue of SCS2, and although it was shown to play a minor role on inositol metabolism (50), we asked if it could function as per Scs2p when cells were overexpressing NTE1. As for the single scs2Δ mutant, the inositol auxotrophy of an scs2Δ scs22Δ double mutant strain was fully alleviated by the overexpression of NTE1 (data not shown). We analyzed by Western blot the effect of overexpressing NTE1 on the levels of Ino1p in scs2Δ mutant cells. A significant increase in the amount of Ino1p protein was detected in the scs2Δ mutant cells overexpressing NTE1 compared with its empty vector control, indicating that NTE1 restores inositol prototrophy to scs2Δ cells by sustaining high levels of Ino1p (Fig. 5A).

With the exception of the inositol auxotrophy triggered by the overexpression of PAH1-encoded PA phosphohydrolase, the ability of NTE1 to alleviate the inositol phenotype of different mutants parallels the inactivation of OPI1. This suggests that the overexpression of NTE1 per se promotes INO1 transcription. Western blot analysis of whole cell extracts obtained from wild type cells overexpressing NTE1 grown under derepressing conditions (5 μm inositol) showed increased levels of Ino1p compared with empty vector control (Fig. 5A). The same analysis performed for cells grown under repressing conditions (75 μm inositol) revealed a substantial level of Ino1p when NTE1 was overexpressed, whereas negligible levels were detected for empty vector control cells (Fig. 5B), as expected for cells growing under repressing conditions. We estimated the transcriptional activity of the INO1 gene promoter by measuring β-galactosidase activity from cells bearing the lacZ gene fused to the INO1 gene promoter on a plasmid. From cells growing under repressing conditions (75 μm inositol), a 25-fold increase in β-galactosidase activity was elicited by the overexpression of NTE1 (1.09 ± 0.22 units/A600) compared with empty vector control (0.04 ± 0.03 units/A600). Using a similar method to measure the activity of CHO1 promoter, we observed a 40% increase of β-galactosidase activity for cells overexpressing NTE1 (1.4 ± 0.07 units/mg) compared with empty vector control (1.0 ± 0.1 units/mg). These changes in promoter reporter activity are consistent with the known regulatory capacity of the UASINO in the context of each promoter. The data are also consistent with the enhanced activity of NTE1-encoded phospholipase B altering the lipid environment and in turn preventing Opi1p repression of transcription leading to increased levels of UASINO-containing gene transcription.

Nte1p and Level of PA

Opi1p binds PA, and compelling evidence shows that the level of PA affects Opi1p repressor activity. Alterations in PC homeostasis produced by changes in the activity of Nte1p phospholipase B could result in changes in PA level and affect Opi1p regulation of gene transcription. Free fatty acids produced from PC degradation mediated by Nte1p could be redirected toward PA synthesis through the fatty acid activation activities of Faa1p and Faa4p (Fig. 1) (the other fatty acid-activating enzymes Faa2p, Faa3p, Fat1p, and Fat2p play a minor role in phospholipid synthesis; for a review see Ref. 52). Hampering fatty acid activation by simultaneous inactivation of the FAA1 and FAA4 genes did not elicit an Ino− phenotype (data not shown) nor prevent the increased expression of Ino1p under repressing conditions mediated by the overexpression of NTE1 (Fig. 5B). This argues against a contribution of the two main fatty acid-activating enzymes for channeling free fatty acids produced by Nte1p into PA synthesis.

To directly assess the contribution of Nte1p-mediated PC turnover on PA levels, we determined the cellular PA content under two different experimental conditions associated with changes in INO1 gene expression as follows: wild type cells overexpressing NTE1 growing under repressing conditions (75 μm inositol) at 25 °C, and nte1Δ cells growing in synthetic media containing 5 μm inositol (derepressing conditions) undergoing high rates of PC synthesis (1 mm choline at 37 °C). We could not detect significant differences in the level of PA in these samples compared with their corresponding controls as follows: wild type cells bearing empty vector under repressing conditions, and wild type and nte1Δ pct1Δ cells growing in 1 mm choline at 37 °C, respectively (data not shown). These results indicate that Nte1p affects regulation of phospholipid synthesis gene transcription without measurable changes in PA levels and suggest that local alterations of membrane composition produced by Nte1p affect the transcription repressing activity of Opi1p.

ER Stress Exacerbates Cellular Demand for Inositol

Inositol availability has a profound impact on yeast cell physiology by affecting phospholipid synthesis and composition. In addition to the signal mediated by Opi1p regulating phospholipid synthesis, other signaling pathways are activated upon inositol starvation as was reflected in the repertoire of genes differentially transcribed in the presence or absence of inositol (32, 36). The UPR pathway was identified as being required to cope with the stress imposed by inositol depletion.

Ire1p is the sensor component of the UPR pathway. It is a multifunctional integral membrane protein localized at the ER that transduces signals of ER stress by catalyzing the maturation of the mRNA encoding the downstream transcriptional activator Hac1p (53). Yeast strains with inactivating mutations in either IRE1 or HAC1 genes are unable to mount the UPR and are also inositol auxotrophs (46, 47). We observed that overexpression of NTE1 alleviated the Ino− phenotype of ire1Δ and hac1Δ mutants (Fig. 6). We next investigated the contribution of NTE1 on the establishment of the UPR by assaying growth in the presence of the ER stress pathway inducer tunicamycin (a protein glycosylation inhibitor) with and without the addition of inositol. Increased NTE1 expression did not provide any extra growth advantage to ire1Δ or hac1Δ cells when growth was assayed in the presence of tunicamycin, either with or without 75 μm inositol (Fig. 6). Analogously, nte1Δ cells showed similar sensitivity to tunicamycin as wild type cells when growth was assayed in the presence of 75 μm inositol. This implies that NTE1 helps cope with ER stress primarily by regulation of INO1 gene induction.

Wild type cells overexpressing NTE1 exhibited reduced sensitivity to tunicamycin compared with empty vector control when assayed on inositol-free medium, whereas this effect was erased when growth was assayed under inositol-replete conditions or in inositol-free medium without tunicamycin (Fig. 6), revealing a strong synergy between inositol limitation and other ER insults. This is consistent with a role for NTE1 to boost the cellular response to ER stress under inositol deprivation along with its ability to promote INO1 gene transcription. Increasing INO1 gene dosage from low copy or high copy plasmids improved the response of wild type or nte1Δ cells to tunicamycin under inositol deprivation consistent with Ino1p acting downstream of NTE1 and stressing the restricting effect of intracellular inositol content (and downstream metabolites) on the outcome of the UPR.

Preventing PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway by disruption of the PCT1 gene led to a slight improvement of the cellular response to tunicamycin compared with wild type cells when growth was assayed in inositol-free media, whereas the simultaneous deletion of the NTE1 gene attenuated this improvement to a level similar to wild type cells (Fig. 6). Interestingly, these differences were erased when growth was assayed in the presence of 75 μm inositol. These results suggest that changes in PC homeostasis, mediated by alteration of Nte1p level or preventing PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway, impact the cellular ability to cope with ER stress mostly by affecting inositol synthesis, as any beneficial or detrimental effect of altered PC homeostasis on the establishment of the UPR under inositol-deplete conditions was eliminated by the addition of 75 μm inositol.

Inositol Deprivation Elicits Increased PC Turnover by NTE1-encoded Phospholipase B

To gain more knowledge about the impact that inositol availability may have on PC metabolism, a radiometabolic experiment was conducted on wild type, nte1Δ, and pct1Δ strains to measure cellular content of choline-containing metabolites. Strains were grown in [3H-methyl]methionine-containing medium in the presence or the absence of 75 μm inositol. The radiolabeled methyl group is transferred from S-adenosylmethionine, a downstream metabolite of methionine, to PE during PC synthesis through the PE methylation pathway. We used strains that are methionine auxotrophs and labeled them to steady state with radioactive methionine of the same specific activity enabling us to make comparisons between treatments and between strains. The labeled PC molecules primarily undergo degradation by NTE1-encoded phospholipase B and SPO14-encoded phospholipase D activities, and their direct products glycerophosphocholine and choline, respectively, are further metabolized and ultimately reused for PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway. Cells were radiolabeled for 7–8 generations to label lipids and metabolites to steady state, and thus the amount of radiolabel present in each metabolite reflects its relative intracellular mass.

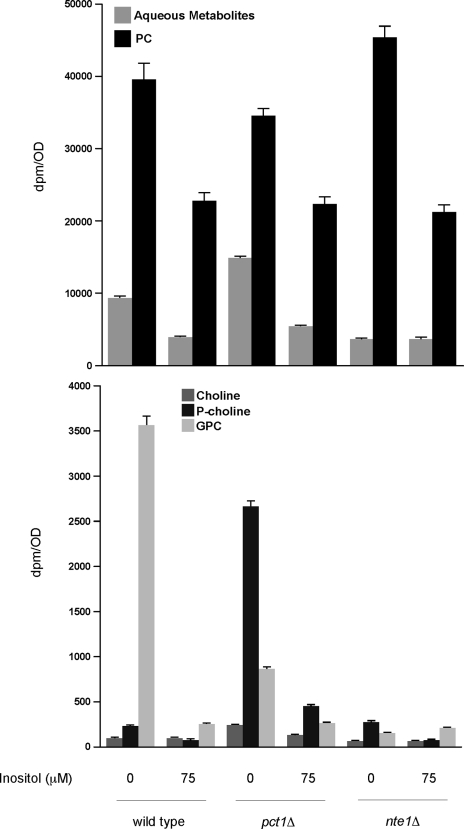

Independent of the strain analyzed, the presence of inositol in the medium led to an ∼40% reduction in the amount of PC compared with cells grown in the absence of inositol (Fig. 7). The PC content of pct1Δ and nte1Δ strains was 10% lower and higher, respectively, than the wild type content when the cells were grown in inositol-free medium. When strains were grown in medium containing 75 μm inositol, the PC content did not differ appreciably between them.

FIGURE 7.

Increased Nte1p mediated PC turnover upon inositol deprivation. Wild type, pct1Δ, and nte1Δ cells were grown to the exponential phase of growth in synthetic media containing 2460 dpm/nmol [methyl-3H]methionine with or without 75 μm inositol at 25 °C. Cells were harvested, washed, and analyzed for radioactivity distribution among the indicated choline-containing metabolites. Data represent mean ± S.E. of a single experiment performed in duplicate. This experiment was repeated three times with qualitatively similar results. GPC, glycerophosphocholine.

Separation and analysis of the aqueous metabolites revealed that besides methionine, the other conspicuous labeled metabolites corresponded to choline, phosphocholine, and glycerophosphocholine. Wild type cells accumulated glycerophosphocholine when grown without exogenous inositol, and this was reduced 15-fold when cells were grown in the presence of 75 μm inositol stressing the extent of PC degradation mediated by NTE1-encoded phospholipase B under inositol-free conditions.

In pct1Δ cells, there was a large accumulation of phosphocholine as PCT1-encoded CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase converts phosphocholine to CDP-choline. The extent of phosphocholine accumulation in pct1Δ cells grown without exogenous inositol was 5-fold higher than in the presence of inositol consistent with PC synthesized by the PE methylation pathway being turned over much more rapidly for subsequent synthesis of PC via the CDP-choline pathway when inositol is not present. Glycerophosphocholine was detected in pct1Δ cells grown in inositol-free medium albeit reduced 4-fold compared with wild type suggesting that PC turnover via Nte1p decreases as the net rate of PC synthesis decreases. However, the accumulation of glycerophosphocholine upon inositol deprivation observed for cells devoid of PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway reveals that NTE1-encoded phospholipase B activity is also sensitive to changes in the rate of PC synthesis through the PE methylation pathway. Consistent with the notion that under inositol-replete conditions the turnover of PC by Nte1p is reduced, the level of glycerophosphocholine was 2.5-fold lower in pct1Δ cells grown in the presence of inositol and comparable with that observed in wild type cells.

Both wild type and pct1Δ strains contained a combined pool of soluble choline-containing metabolites of around 10% relative to the label associated with PC when grown without exogenous inositol, in sharp contrast to nte1Δ cells where very low levels of soluble choline containing metabolites were detected. Only trace levels of glycerophosphocholine were observed, and this was expected as Nte1p is responsible for its intracellular formation. In the absence of NTE1-encoded phospholipase B activity, any choline molecule generated intracellularly is either recycled back into PC through the CDP-choline pathway or excreted out of the cell.

For yeast cells growing without exogenous inositol, the flux through the CDP-DAG and CDP-choline branches for PC synthesis are high as the genes coding for enzymes involved in those pathways are transcriptionally activated due to the presence of the upstream UASINO motif. In fact, cellular PC content is maximal under inositol deprivation. The effect of inositol availability on glycerophosphocholine accumulation indicates that NTE1-encoded phospholipase B responds to changes on the rate of PC synthesis per se.

Regulation of PC Synthesis through the CDP-choline Pathway upon Choline Supplementation

NTE1 contribution to PC homeostasis becomes essential under conditions of high rates of PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway elicited by choline supplementation at 37 °C. Preventing choline uptake by inactivation of the HNM1 gene alleviated the inositol auxotrophy of nte1Δ cells at 37 °C suggesting that the increase in the rate of PC synthesis reported at 37 °C depends on exogenous choline. We asked about the role of choline uptake by the HNM1-encoded choline transporter on the increased rate of PC synthesis upon temperature shift to 37 °C. We detected a 3-fold increase in the rate of choline uptake at 37 °C compared with 25 °C (Table 5), and this required HNM1. The increase in choline uptake at 37 °C correlates with the doubling of the rate of PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway at this temperature (38). This result highlights the important role of the Hnm1p choline transporter in controlling PC synthesis upon choline supplementation, and it prompted us to investigate the role of choline and inositol on the regulation of Hnm1p level and activity and the effect of NTE1 on Hnm1p function.

TABLE 5.

Effect of growth temperature on the rate of choline transport

Wild type cells bearing a TAP-tagged allele of the HNM1 gene were grown to mid-log phase in synthetic media containing 1 mm choline at the indicated temperatures. Cells were thoroughly washed in choline-free media prewarmed at the corresponding temperature, and choline uptake was assayed as described under “Materials and Methods.” Choline uptake was <10% wild type in cells when the gene for the high affinity choline transport, HNM1, was inactivated. The remaining choline transport activity present in hnm1Δ cells was unchanged with growth temperature.

| Temperature growth | Choline uptake |

|---|---|

| °C | pmol/min OD |

| 25 | 33 ± 3 |

| 37 | 94 ± 10 |

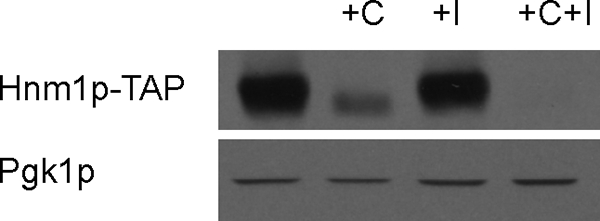

We analyzed the effect of choline and inositol supplementation on the steady state levels of Hnm1p. We took advantage of a strain containing a fully functional TAP-tagged variant of the HNM1 open reading frame inserted into the HNM1 locus to estimate Hnm1p protein level by Western blot. Consistent with the reported reduction of choline uptake by supplementation of choline alone (54, 55), we detected a substantial decrease in the level of Hnm1p-TAP protein from cells grown in 1 mm choline-containing media (Fig. 8). The simultaneous addition of 75 μm inositol further reduced the level of Hnm1p, whereas it was only slightly affected by inositol alone. Northern blot and microarray analyses have shown that the simultaneous addition of inositol and choline is necessary to repress the expression of the HNM1 gene, whereas inositol alone does not elicit any appreciable effect (32, 55). These results reveal that the observed reduction of choline uptake upon choline addition is due to a decreased level of Hnm1p. Because no changes on the HNM1 gene mRNA levels have been reported to occur in response to choline supplementation, an uncharacterized regulatory mechanism controls Hnm1p levels upon choline addition.

FIGURE 8.

Effect of choline and inositol supplementation on the level of the HNM1-encoded choline transporter. Wild type cells carrying a TAP-tagged allele of HNM1 were grown to mid-log phase at 25 °C in synthetic media containing or not 75 μm inositol and/or 1 mm choline as indicated. Whole cell extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis using a rabbit anti-TAP polyclonal antibody (upper panel) and reprobed with a mouse anti-Pgk1p monoclonal antibody (lower panel) as load control.

To investigate the role of NTE1 on the reduction of choline uptake triggered by choline supplementation, we measured choline uptake rates on wild type and nte1Δ cells grown with or without 1 mm choline. Choline was taken up by nte1Δ cells at a rate 30% lower than wild type cells when grown without exogenous choline, whereas the presence of 1 mm choline in the growth media severely reduced the rate of transport for both strains to a similar level (data not shown) indicating that the regulation of the choline transporter upon choline supplementation does not depend on Nte1p-mediated PC turnover.

We further inquired about the role of NTE1 controlling PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway. We performed radiolabeled choline pulse experiments up to 150 min in wild type and nte1Δ cells growing in inositol-free medium at 25 °C. Analogous to what was reported for nte1Δ cells growing in inositol- and choline-containing medium at 37 °C (1), we measured only a slight decrease in PC synthesis in nte1Δ cells compared with wild type (data not shown) indicating that Nte1p does not moderate the rate of PC synthesis.

These results taken together reveal that Nte1p does not have a direct role in controlling PC synthesis indicating that its function in preventing phospholipid synthesis gene repression takes place upon increased rates of PC synthesis. In addition, these results point to the HNM1-encoded choline transporter as an important regulator of PC synthesis under conditions of choline supplementation.

DISCUSSION

Nte1p Regulation of Phospholipid Biosynthetic Gene Transcription

In this study, we demonstrate that Nte1p phospholipase B activity is required to allow proper transcriptional regulation of UASINO-containing genes in response to inositol availability. We show that under conditions of high rates of PC synthesis through the CDP-choline pathway, PC degradation by Nte1p prevents Opi1p nucleoplasmic localization allowing for a sustained high level of INO1 mRNA and Ino1p protein. We also show that overexpression of NTE1 promotes UASINO-containing gene transcription under repressing and nonrepressing conditions, providing further support to the notion of a dynamic source-sink interplay between PC turnover by NTE1 and regulation of phospholipid gene transcription.

The ability of increased NTE1 expression to alleviate a wide spectrum of inositol auxotroph mutants and to induce UASINO-containing gene expression under repressing conditions resembles the effect of loss of Opi1p function. This implies that NTE1 produces a signal that inhibits Opi1p function. What is the metabolic consequence of NTE1 activity that sustains phospholipid gene transcription? One obvious possibility is the generation of free fatty acids for PA synthesis. However, a faa1Δ faa4Δ double mutant strain with a major impairment in activation of free fatty acids to channel into PA synthesis was not an inositol auxotroph, and it exhibited a level of Ino1p similar to wild type cells (if not higher) when NTE1 was overexpressed under repressing conditions.

It has been observed that upon the addition of inositol there is a dramatic increase in the rate of PI synthesis simultaneously with a burst of Nte1p-mediated PC turnover (56). Interestingly, the rate of PI synthesis was unaffected in nte1Δ cells indicating that PC turnover mediated by Nte1p upon inositol addition is not an immediate source of fatty acids for the sustained increase in PI synthesis (56). This is consistent with the idea that the lack of contribution of free fatty acids for PA synthesis is not the only cause of the Ino− phenotype of nte1Δ cells. Direct measurement of PA content in nte1Δ cells growing at 37 °C in the presence of choline did not reveal any significant decrease compared with wild type cells growing under the same conditions. A dedicated highly localized pool of PA could serve to control the activity of Opi1p, but this would not be detected in whole cell measurements.

There are three metabolic outputs of Nte1p activity that are relevant toward phospholipid homeostasis (Fig. 1) as follows: first, Nte1p reduces PC content, at least locally at the ER; second, along with GDE1-encoded glycerophosphocholine glycerophosphodiesterase (57, 58), it controls PC resynthesis; and third it generates free fatty acids. For cells growing without inositol, the PC content of the ER membrane is very high, especially when choline is supplied at 37 °C. Phospholipid precursors are consumed, and PC becomes more abundant leading to increased lateral packing that could affect functions of some ER components. We are tempted to speculate that the interaction of Opi1p with Scs2p and the ER membrane is sensitive to this parameter. Increasing lateral packing attenuates the interaction of Opi1p with its anchors reducing phospholipid gene transcription. Contrarily, low lateral packing reinforces the interaction between Opi1p and ER membranes, promoting phospholipid gene transcription. Nte1p contributes toward phospholipid homeostasis by directly affecting membrane packing at the ER (Fig. 9B).

Contribution of Nte1p to Regulation of Phospholipid Metabolism and Maintenance of Phospholipid Heterogeneity

Pulse-chase analysis of phospholipid metabolism in yeast showed an increase in PC labeling at the expense of all other phospholipids over time (59). This illustrates the fact that PC is the end product of phospholipid synthesis through both the CDP-choline and CDP-DAG branches, effectively functioning as a metabolic sink for metabolism of the major phospholipids PE and PS. We are envisioning a mechanism performed by Nte1p that contributes to the generation and maintenance of phospholipid heterogeneity. Under inositol-rich conditions, transcription of the genes responsible for the synthesis of phospholipid genes is repressed, and PI and PC content are 25 and 45%, respectively, of total phospholipid. Under inositol deprivation, the transcription of UASINO-containing genes is induced, with high rates of PC synthesis, and the marginal formation of PI is solely dependent on de novo synthesis of inositol resulting in a PC and PI content of around 55 and 10%, respectively. In this scenario, the phospholipase B activity of Nte1p is maximal as is inferred from the accumulation of glycerophosphocholine reported here. The physiological outcome of this augmented Nte1p activity is not the slowing down of phospholipid synthesis to balance increased turnover by Nte1p, on the contrary the results presented here indicate that the degradation of PC mediated by Nte1p further sustains phospholipid synthesis. Nte1p degrades PC-generating glycerophosphocholine whose intracellular concentration can vary greatly and reach millimolar levels before it is degraded by the GDE1-encoded glycerophosphocholine glycerophosphodiesterase to choline and glycerophosphate. This allows for a metabolic loop to divert in a regulated manner choline headgroups from PC resynthesis by PC turnover via Nte1p. This metabolic loop provided by Nte1p may constitute another layer of regulation toward maintaining phospholipid heterogeneity in concert with its regulation of UASINO-containing gene transcription.

Nte1p Regulation of Cell Stress

Yeast cells growing in inositol-free medium have a distinguishing phospholipid composition characterized by an extreme PC/PI ratio as a result of marginal formation of PI and very high rates of PC synthesis. The UPR and CWI pathways are both activated under this growth condition indicating that this phospholipid composition somehow hampers normal ER function and confers cell stress (22, 32, 36, 40). Consistent with the notion of a synthetic impairment between challenged ER function and inositol deprivation, we observed a substantial improvement in the cellular performance of wild type cells exposed to the UPR inducer tunicamycin in medium augmented with inositol. In the absence of exogenous inositol, inactivation of OPI1 gene, as well as overexpression of NTE1 or INO1, restored growth to cells challenged with tunicamycin to a level comparable with cells growing in inositol-containing medium in the presence of the same concentration of the drug. Acquiring a higher PI membrane content substantially improves survival in response to ER stress.

It was recently reported that pkc1Δ, bck1Δ, and mpk1Δ mutant strains, all defective for the CWI pathway, are inositol auxotrophs (40). It was demonstrated for mpk1Δ cells that the steady state level of INO1 mRNA was not decreased. Instead, this mutant exhibited an altered phospholipid metabolic profile characterized by increased PC content. Based on the fact that NTE1 overexpression alleviated the Ino− phenotype of mpk1Δ mutant cells, it was suggested that a decrease in PC level at the ER mediated by Nte1p restores phospholipid homeostasis and prevents cell death due to the combination of an inactive CWI pathway and abnormal membrane phospholipid composition (40). Our data indicate that Nte1p contributes to restore phospholipid homeostasis at the ER by not only affecting PC content but also increasing PI synthesis by promoting INO1 gene expression.

It is worth highlighting that the Ino− phenotype is not necessarily an exclusive reporter of INO1 gene transcription. The case of mpk1Δ cells together with our data showing the sensitizing effect of inositol deprivation on wild type cells challenged with tunicamycin are consistent with the idea that the Ino− phenotype is also a readout of the cellular ability to cope with ER stress. An increase in the cellular demand for inositol might be due to the phospholipid complement of the ER becoming the limiting factor for overall ER performance. Even though the rate of INO1 gene transcription remains maximal, in the absence of inositol the level of PI and the PC/PI ratio are skewed. Changing the ER phospholipid composition from the extreme condition found in cells growing without inositol contributes to improving the function of the ER.

In summary, we have furthered the understanding of the cellular function of the phospholipase B Nte1p. Nte1p plays an essential role under conditions of high rates of PC synthesis by sustaining phospholipid synthesis gene transcription by preventing Opi1p nucleoplasmic localization. This ensures cells can maintain the proper phospholipid heterogeneity required for membranes to function in response to membrane stress.

Acknowledgment

We thank Susan Henry for advice during the course of this work and for critical comments on the written manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM019629 (to S. Henry supporting the work of S. A. J. and collaborative studies between the McMaster and Henry laboratories). This work was also supported by Canadian Institutes for Health Research Grant 14124 (to C. R. M.).

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- PI

- phosphatidylinositol

- PA

- phosphatidic acid

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- UPR

- unfolded protein response

- CWI

- cell wall integrity pathway

- UASINO

- inositol responsive upstream activation sequence

- Ino−

- inositol-requiring

- TAP

- tandem affinity purification.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zaccheo O., Dinsdale D., Meacock P. A., Glynn P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24024–24033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez-Murray J. P., McMaster C. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8544–8552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glynn P. (2006) Toxicol. Lett. 162, 94–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glynn P. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1736, 87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rainier S., Bui M., Mark E., Thomas D., Tokarz D., Ming L., Delaney C., Richardson R. J., Albers J. W., Matsunami N., Stevens J., Coon H., Leppert M., Fink J. K. (2008) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82, 780–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moser M., Li Y., Vaupel K., Kretzschmar D., Kluge R., Glynn P., Buettner R. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1667–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winrow C. J., Hemming M. L., Allen D. M., Quistad G. B., Casida J. E., Barlow C. (2003) Nat. Genet. 33, 477–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akassoglou K., Malester B., Xu J., Tessarollo L., Rosenbluth J., Chao M. V. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 5075–5080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kretzschmar D., Hasan G., Sharma S., Heisenberg M., Benzer S. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 7425–7432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mühlig-Versen M., da Cruz A. B., Tschäpe J. A., Moser M., Büttner R., Athenstaedt K., Glynn P., Kretzschmar D. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 2865–2873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMaster C. R., Jackson T. R. (2004) in Topics in Current Genetics: Lipid Metabolism and Membrane Biogenesis (Daum G. ed) Vol. 6, pp. 5–88, Springer-Verlag, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newton A. C. (2004) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 25, 175–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peter C., Waibel M., Radu C. G., Yang L. V., Witte O. N., Schulze-Osthoff K., Wesselborg S., Lauber K. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5296–5305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serhan C. N., Yacoubian S., Yang R. (2008) Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3, 279–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carman G. M., Henry S. A. (1999) Prog. Lipid. Res. 38, 361–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry S. A., Patton-Vogt J. L. (1998) Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 61, 133–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg M. L., Lopes J. M. (1996) Microbiol. Rev. 60, 1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carman G. M., Han G. S. (2008) J. Lipid Res. 50, S69–S73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loewen C. J., Gaspar M. L., Jesch S. A., Delon C., Ktistakis N. T., Henry S. A., Levine T. P. (2004) Science 304, 1644–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobrosotskaya I. Y., Seegmiller A. C., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L., Rawson R. B. (2002) Science 296, 879–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoppe T., Matuschewski K., Rape M., Schlenker S., Ulrich H. D., Jentsch S. (2000) Cell 102, 577–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brickner J. H., Walter P. (2004) PLoS Biol. 2, e342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loewen C. J., Roy A., Levine T. P. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 2025–2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carman G. M., Henry S. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37293–37297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos-Rosa H., Leung J., Grimsey N., Peak-Chew S., Siniossoglou S. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 1931–1941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Hara L., Han G. S., Peak-Chew S., Grimsey N., Carman G. M., Siniossoglou S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34537–34548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han G. S., O'Hara L., Carman G. M., Siniossoglou S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20433–20442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han G. S., O'Hara L., Siniossoglou S., Carman G. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20443–20453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han G. S., Siniossoglou S., Carman G. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37026–37035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han G. S., Wu W. I., Carman G. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9210–9218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kagiwada S., Zen R. (2003) J. Biochem. 133, 515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jesch S. A., Zhao X., Wells M. T., Henry S. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9106–9118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein A. L., McCusker J. H. (1999) Yeast 15, 1541–1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voth W. P., Jiang Y. W., Stillman D. J. (2003) Yeast 20, 985–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., 3rd, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. (1998) Yeast 14, 953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jesch S. A., Liu P., Zhao X., Wells M. T., Henry S. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24070–24083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fairn G. D., Curwin A. J., Stefan C. J., McMaster C. R. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15352–15357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dowd S. R., Bier M. E., Patton-Vogt J. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3756–3763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bailis A. M., Lopes J. M., Kohlwein S. D., Henry S. A. (1992) Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 1411–1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nunez L. R., Jesch S. A., Gaspar M. L., Almaguer C., Villa-Garcia M., Ruiz-Noriega M., Patton-Vogt J., Henry S. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 34204–34217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ford J., Odeyale O., Eskandar A., Kouba N., Shen C. H. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 361, 974–979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ford J., Odeyale O., Shen C. H. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 373, 602–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kodaki T., Hosaka K., Nikawa J., Yamashita S. (1995) J. Biochem. 117, 362–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ebbert R., Birkmann A., Schüller H. J. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 32, 741–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirra M. K., Patton-Vogt J., Ulrich A., Liuta-Tehlivets O., Kohlwein S. D., Henry S. A., Arndt K. M. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 5710–5722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cox J. S., Chapman R. E., Walter P. (1997) Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1805–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nikawa J., Yamashita S. (1992) Mol. Microbiol. 6, 1441–1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hosaka K., Nikawa J., Kodaki T., Ishizu H., Yamashita S. (1994) J. Biochem. 116, 1317–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kadereit B., Kumar P., Wang W. J., Miranda D., Snapp E. L., Severina N., Torregroza I., Evans T., Silver D. L. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 94–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loewen C. J., Levine T. P. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14097–14104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaiser S. E., Brickner J. H., Reilein A. R., Fenn T. D., Walter P., Brunger A. T. (2005) Structure 13, 1035–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Black P. N., DiRusso C. C. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 286–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patil C., Walter P. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McMaster C. R., Bell R. M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14776–14783 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nikawa J., Hosaka K., Tsukagoshi Y., Yamashita S. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 15996–16003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaspar M. L., Aregullin M. A., Jesch S. A., Henry S. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22773–22785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fisher E., Almaguer C., Holic R., Griac P., Patton-Vogt J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36110–36117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernández-Murray J. P., McMaster C. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38290–38296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patton-Vogt J. L., Griac P., Sreenivas A., Bruno V., Dowd S., Swede M. J., Henry S. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20873–20883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen X., Xiao H., Ranallo R., Wu W. H., Wu C. (2003) Science 299, 112–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]