Abstract

(23S)-25-Dehydro-1α(OH)-vitamin D3-26,23-lactone (MK) is an antagonist of the 1α,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 (1,25D)/human nuclear vitamin D receptor (hVDR) transcription initiation complex, where the activation helix (i.e. helix-12) is closed. To study the mode of antagonism of MK an hVDR mutant library was designed to alter the free molecular volume in the region of the hVDR ligand binding pocket occupied by the ligand side-chain atoms (i.e. proximal to helix-12). The 1,25D-hVDR structure-function studies demonstrate that 1) van der Waals contacts between helix-12 residues Leu-414 and Val-418 and 1,25D enhance the stability of the closed helix-12 conformer and 2) removal of the side-chain H-bonds to His-305(F) and/or His-397(F) have no effect on 1,25D transactivation, even though they reduce the binding affinity of 1,25D. The MK structure-function results demonstrate that the His-305, Leu-404, Leu-414, and Val-418 mutations, which increase the free volume of the hVDR ligand binding pocket, significantly enhance MK antagonist potency. Surprisingly, the H305F and H305F/H397F mutations turn MK into a VDR superagonist (EC50 ∼ 0.05 nm) but do not concomitantly alter MK binding affinity. Molecular modeling studies demonstrate that MK antagonism stems from its side chain energetically preferring a pose in the VDR ligand binding pocket where its terminal C26-methylene atom is far removed from helix-12. MK superagonism results from an energetically favored increase in interaction between Leu-404/Val-418 and C26, resulting in an increase in the stability and population of the closed, helix-12 conformer. Finally, the results/model generated, coupled with application of a VDR ensemble allosterics model, provide an understanding for the species specificity of MK.

Introduction

The steroid hormone 1α,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 (1,25D)2 (see Fig. 1) and the nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR) forms a complex that modulates the transcription of genes containing a VDR element. This process is termed a genomic response and involves 1,25D binding to the VDR, formation of a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor, and recruitment of nuclear co-activators (NCoAs) and the basal transcription machinery (1).

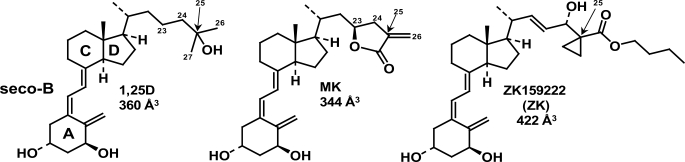

FIGURE 1.

The chemistry of 1,25D, MK, and ZK. The chemical structures of 1α,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 (1,25D, C27H44O3) and the genomic antagonists of 1,25D-hVDR-mediated transactivation, MK (C27H38O4 (TEI-9647, Teijin Pharma)), and ZK (C32H48O5 (ZK159222, Schering)). The A, seco-B, C, and D rings of 1,25D are labeled, as are the side-chain carbon atoms C23, C24, C25 (arrow), C26, and C27. The molecular volumes of 1,25D, MK, and ZK were determined using DS2.0 (see “Experimental Procedures”).

The VDR is a member of the nuclear hormone superfamily of transcription factors, all of which share similar domain partitioning, ligand binding domain (LBD) tertiary fold and localization of their ligand binding pocket (LBP). The current induced-fit model describing nuclear receptor (NR) activation (i.e. the mouse-trap model) is founded on the comparison of apo- and holo-NR x-ray crystal structures. The mouse trap model posits that closure of the NR activation helix (i.e. helix-12) is induced by ligand binding to an opened-like helix-12 apo-NR conformer. The closed helix-12 conformation completes the activation function II domain (AF2), which serves as the high affinity binding site for recruitment of various NCoAs (1–4) (Fig. 2). Thus, the steric blockage of NR helix-12 closure is the basis for the design of traditional NR genomic antagonists (5–9).

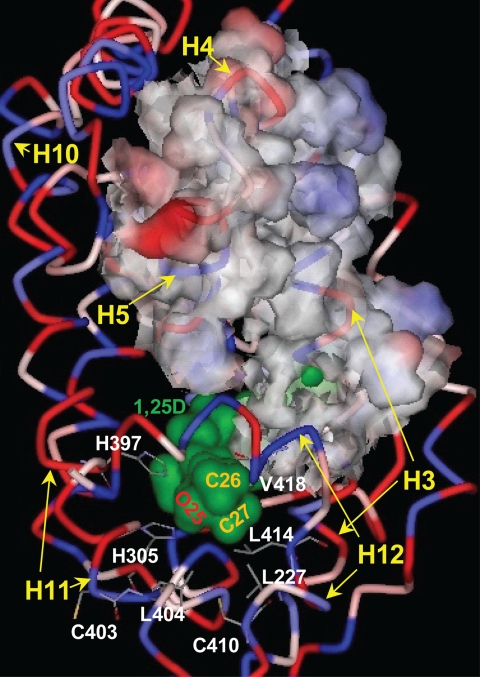

FIGURE 2.

The 1,25D-hVDR complex. The hVDR (LBD, aa 120–427, Δ165–215) is rendered to depict its ribbon structure and the relative hydrophobicity of its amino acid R-groups (blue, hydrophobic; red, polar, charged; pink-white, polar, uncharged). 1,25D is surface-rendered to illustrate its van der Waals (vdW) surface (green) and the location of the hVDR LBP. The position of the 1,25D C25 hydroxyl group and the C26/C27 side-chain methyl groups are labeled. The methyl groups lie proximal to Leu-227 helix-3 (H3), Leu-404 (H11), Leu-414 (H12), and Val-418 (H12), which form the hVDR LBP helix-3/helix-12 interface. The 25-OH group of 1,25D forms H-bonds with His-305 and His-397. The His-305 and Leu-404 residues form the bottom of the hVDR LBP. The upper surface of the nuclear co-activator (NCoA) binding site is highlighted by rendering the surface of amino acids 233 (H3) through 264 (H5) visible. The bottom of the NCoA surface is formed by helix-12 (H12). Helices 10 (H10) and 11 (H11) are labeled for reference.

1,25D-VDR-induced genomic responses can be blocked by co-incubation with a 10-fold excess of analog MK or ZK159222 (ZK, Fig. 1); however, the mode of antagonism is different for these two molecules (7, 10). The ZK side-chain molecular volume is significantly enhanced relative to 1,25D; therefore, ZK acts as a traditional NR antagonist by blocking VDR helix-12 closure (5). Two mechanisms have been proposed to explain MK antagonism; both are based on the inability of MK to function as an antagonist in the rodent VDR (rVDR). One current hypothesis suggests that the α/β-unsaturated exo-cyclic methylene of MK (Fig. 1) undergoes a 1,4-Michael addition (i.e. formation of a covalent MK-VDR adduct) with Cys-403 and/or Cys-410 of the human VDR (hVDR), neither of which are present in the rVDR primary sequence (10). Yet another hypothesis proposes that the energetic stability of the rVDR closed helix-12 conformer is enhanced relative to hVDR (7). Thus the detailed allosterics underlying MK antagonism of 1,25D-hVDR-mediated transactivation remains an important, unresolved question in light of the proposed use of MK or its analogs as a potential treatment for Paget disease (12).

To date no x-ray complex of the MK·hVDR complex is available. Therefore, to gain a molecular understanding to MK antagonism of 1,25D-hVDR gene activation and species specificity (7, 10, 13–17) we applied traditional structure-function assays, molecular modeling, and a vitamin D sterol-VDR conformational ensemble model (18, 19). Our comprehensive structure-function studies demonstrate that MK antagonism hinges on its reduced side-chain molecular volume allowing it to bind favorably to two distinct regions within the hVDRwt LBP. Furthermore, we show for the first time in the NR field that a known antagonist (MK) can be converted into a superagonist ligand by a conservative single point mutation and provide further evidence in support of the VDR ensemble model (18–21).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Volume Calculations

The molecular volume of 1,25D, MK, and ZK was determined using Discovery Studio 2.0 (Molecular Attributes, Accelrys Inc.) and atom typing with the cff forcefield. For 1,25D and ZK the conformation used for the calculation was taken from the pose observed in their reported VDR LBD x-ray .pdb files. For MK the lowest energy complex determined using the flexible docking protocol (see below) was used to calculate the molecular volume. The molecular volumes of the hVDRwt ligand binding pocket (LBP) and the His-305, His-397, Leu-404, Leu-414, and Val-418 mutants were calculated following mutant generation and side-chain refinement in DS2.0. Following refinement the Receptor-Ligand Interaction/Binding Site/Find Sites from Receptor Cavities tool in DS2.0 was used to determine the molecular volume of the LBP.

EC50 Determination in CV1 Cells

Cells were seeded at 0.4 × 105 cells per well on 24-well plates (BD Biosciences) in minimal Eagle medium with Earle's buffered salts and non-essential amino acids, with 10% fetal bovine serum (Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA). After 24-h incubation, phosphate-buffered saline-washed cells, at ∼60% confluence, were transfected using a 10-min pre-treatment with 0.2 mg/ml DEAE-dextran (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline. Pre-treated cells were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated for 30 min with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1 μg/well activator pcDNA3.1(−)Nhe1(−)VDR or mutant plasmid and 0.5 μg/well reporter OC-pSEAP2 (secreted alkaline phosphatase) (22). Transfected cells were incubated in 80 μm chloroquine in growth media with 5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum for 4 h followed by the same culture medium without chloroquine for 24 h. At 28 h post transfection, the cell medium was replaced with the same medium containing various concentrations of 1,25D or its analogs, with a final ethanol concentration of 0.1%. In all antagonism studies first the 1,25D EC50 in the given VDR construct was experimentally derived (n ≥ 3), then a 10-fold excess of MK was co-incubated with the EC50 concentration of 1,25D (see supplemental materials). At 22 h after analog treatment, an aliquot of the cell medium was harvested to measure secreted alkaline phosphatase using the Phospha-LightTM Kit (Tropix, Bedford, MA). The concentration of steroid producing 50% (EC50) of the maximal activity was then determined using Prism v5.0.

Protease Sensitivity Assay

[35S]-VDR was generated from pcDNA3.1(−)Nhe1(−)VDR or mutant VDR plasmid constructs using the Promega TNT reticulocyte lysate kit. The reaction tubes were incubated for 2 h at 30 °C then placed on ice. 1,25D or analog was added, and the tubes were incubated at room temperature for 20 min. 15 μg/ml trypsin was added to the tubes and incubated for 20 min at room temperature followed by 5.0-min incubation at 80 °C with SDS. Reaction mixtures were then loaded in a 12.5% or 15% SDS-PAGE gel and subjected to electrophoresis. Bands were visualized by autoradiography. The molecular weight of each band was calculated using Stratagene EagleSight software (v3.0.001).

1,25D/MK-VDR Binding Analyses

BL21-DE3 cells (Stratagene) were transformed with the pET15b vector containing human VDR LBD (aa 118–427; Δ165–215) obtained from the Moras laboratory (Institute of Genetics and Molecular and Cellular Biology, Strasbourg, France). Following culture scale-up to 1 liter (37 °C), cells were grown to an A600 of 0.5–0.6 (37 °C and 250 rpm), induced with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, grown at 20 °C for 6 h, and pelleted at 4,000 × g for 10 min (4 °C). The pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (5 mm imidazole, 20 mm Tris (pH 8.5), 10% glycerol, 250 mm NaCl, 1 mm protease inhibitor cocktail, and 1 mm dithiothreitol) and lysed by sonication (15-s pulse, 1 min on ice, repeated 3×). After centrifugation (12,000 × g), the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm syringe filters (Millipore), flash frozen, and stored at −80 °C.

To determine the affinity of ligands for the hVDR, 0.05 pmol of [3H]1,25D in EtOH was added to borosilicate glass tubes (Fisher). Increasing concentrations of cold ligands were added to the tubes in duplicate, and total EtOH was adjusted to 20 μl. 230 μl (25 μg of total protein, determined by Bradford) of the diluted, clarified VDR-LBD was added to each tube, briefly vortexed, and placed at 4 °C for 4–24 h (buffer same as lysis buffer minus protease inhibitor cocktail and pH 8.0). Following incubation, 250 μl of 50% (v/v) hydroxyapatite solution in TED (10 mm Tris-base, 1.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol) was added and washed three times with 1 ml of TED plus 0.5% Triton X-100. Bound [3H]1,25D was eluted with 1 ml of ethanol and counted in 7 ml of Liquiscint (National Diagnostics) scintillation mixture using a Beckman LS6500. Data from duplicate samples were averaged and plotted as % max bound [3H]1,25D versus the log of the concentration of the competitor used. Non-linear regression using Prism® (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was performed to determine the IC50, correlation coefficient, and R2 values. Data were also plotted to generate a relative competitive index value (21).

PC_Model v8.0 Calculations

Whole molecule GMMX (Global-MMX) experiments were carried out on 1,25D and MK allowing for flexibility in the A-ring, seco-B-ring, and side-chain single bonds of both molecules (Fig. 1). The following GMMX variables were used: search on bonds only, π-correction turned on, energy window of 11.0 kcal/mol, and 1000 total conformers generated. After the manual check of the sp2-hybridized atoms, the 1,25D and MK conformer sets were typed with the cff forcefield (DS2.0) and used for the flexible docking simulation.

Flexible Docking Protocol

The complex formation between the apo-hVDR molecules and the PC_Model ligand conformers was simulated by applying a flexible docking protocol (DS2.0). To simulate the 1,25D and MK complex formation with the hVDRwt LBP and its mutants, 50 hVDR LBP conformations were first generated (this includes the hVDRwt LBD). Flexibility was allowed in the following R-groups: Tyr-143, Tyr-147, Asp-149, Phe-150, Phe-153, Leu-227, Ala-231, Leu-233, Val-234, Tyr-236, Ser-237, Ile-268, Met-272, Arg-274, Ser-275, Ser-278, Trp-286, Cys-288, Tyr-295, Asp-299, Val-300, Ala-303, Gly-304, His-305, Leu-309, Ile-310, Leu-313, His-397, Tyr-401, Leu-404, Leu-414, Thr-415, Val-418, and Phe-422 (i.e. the flexible docking residues, these residues form the VDR LBP). In all of the calculations the VDR conformational isomers were generated and the protocol stopped, so that the same set of VDR LBP conformers was sourced in all the simulations. The flexible docking protocol variables changed from the default parameters were as follows: a 10.0-Å docking sphere was defined by searching the apo-VDR molecule for putative binding sites; the number of flexible docking residues allowed for structural refinement was set to 12; the top 5 hits were saved for each protein-ligand pair, and a simulated annealing step was performed. The Generalized Born with Molecular Volume method (23, 24) was used to determine the ΔGbinding value (ΔGbinding = ΔGholo-VDR − ΔGapo-VDR − ΔGligand), where the only default values changed were the cutoff distances, which were changed from 14, 12, and 10 Å, to 10, 8, and 6 Å, respectively. For a more detailed description of the computational techniques/protocols employed herein see the supplemental materials.

RESULTS

vdW Contacts Made with Helix-3 and Helix-12 Residues Are Crucial to 1,25D-hVDR Transactivation

Based on the hVDR x-ray crystallographic results (5, 25–27) His-305 and His-397 form hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) with the 25-OH group of 1,25D (28, 29) (Fig. 2). These H-bonds effectively anchor the terminal methyl groups (Cys-26 and Cys-27 (Fig. 2)) of the 1,25D side chain to form favorable hydrophobic van der Waals (vdW) interactions with Leu-227 (helix-3), Leu-414 (helix-12), and Val-418 (helix-12 (Fig. 2)). The hydrophobic interactions made with theses three residues aid in stabilizing the intramolecular interaction between helix-3 and helix-12 and thereby the closed conformation of helix-12 (i.e. the activation helix (Fig. 2)).

To study the impact that expanding or shrinking the free molecular volume of the VDR LBP proximal to the helix-3/helix-12 interface (Fig. 2) has on 1,25D-hVDR transactivation, we generated seven conservative hVDR point mutants. These were used to determine the 1,25D effective concentration (EC50) required to induce the expression of an osteocalcin-driven SEAP reporter, in CV1 cells (Table 1). The transactivation results demonstrated that all of the hVDR mutant constructs that increase the free molecular volume proximal to the helix-3/helix-12 interface suppressed 1,25D transactivation. In contrast, mutations made that reduced the free molecular volume, had little or no effect on the 1,25D EC50 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

The molecular volume of Leu-404, Leu-414, and Val-418 hVDR LBP mutants and 1,25Ds effective concentration (EC50)

Each hVDRwt mutation was made, and the molecular volume was calculated using the Discover Studio software package (see “Experimental Procedures” for protocol). CV cells were transiently co-transfected with an osteocalcin-driven SEAP reporter and a hVDR construct and the 1,25D EC50 was measured (n values presented in table). All EC50 values are statistically (p ≤ 0.05) greater than hVDRwt with the exception of V418L. Representative dose-response curves are provided in supplemental Fig. 1.

| Construct | LBP molecular volume | 1,25D EC50 |

|---|---|---|

| Å3 | nm | |

| hVDRwt | 406 | 1.4 ± 0.15 (n = 20) |

| L404V | 431 | 37 ± 1.6 (n = 3) |

| L414V | 434 | 28 ± 4.3 (n = 3) |

| V418A | 416 | 74 ± 24 (n = 3) |

| V418L | 399 | 1.8 ± 0.81 (n = 3) |

| L404V/V418L | 424 | 390 ± 150 (n = 3) |

| L404V/L414V | 448 | 69 ± 17 (n = 3) |

| L404F/V418L | 406 | 6.5 ± 1.5 (n = 3) |

Effect of Helix-3/Helix-12 Interface Mutations on MK Antagonist Potency

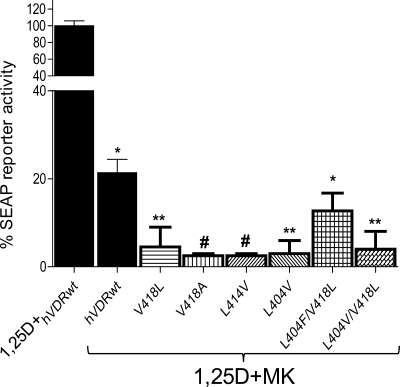

Co-incubation of 10 nm MK with 1 nm 1,25D significantly hindered the ability of 1,25D to act as a potent genomic agonist in CV1 cells transiently transfected with hVDRwt (Fig. 3). When a 10-fold excess of MK was combined with an EC50 dose of 1,25D in the helix-3/helix-12 interface mutants (Table 1), MK antagonist potency was significantly enhanced by all of the hVDR mutants that increased the free molecular volume of the hVDR LBP (Figs. 2 and 3). These results were somewhat expected given MK had a reduced side-chain molecular volume (344 Å3) when compared with 1,25D (360 Å3 (Fig. 1)).

FIGURE 3.

Helix-3/helix-12 interface mutations increase the MK antagonist effect. CV1 cells were co-transfected with the osteocalcin VDR element-driven SEAP reporter and hVDRwt, L404V, L414V, V418A, V418L, L404F/V418L, and L404V/V418L plasmid constructs. The effective concentration (EC50, half-maximal activity) of 1,25D was measured in all the hVDR constructs, and a summary is provided in Table 1. The figure illustrates the % 1,25D SEAP activity measured when the cells were dosed with an EC50 concentration of 1,25D and a 10-fold excess of MK (n = 3). The values are expressed relative to the activity observed for 1,25D alone in each mutant, normalized to 100%. See supplemental Fig. 1 for representative 1,25D dose-response curves for these mutants. The ligand concentrations used are as follows: hVDRwt (1,25D = 1 nm; MK = 10 nm), L404V (1,25D = 40 nm; MK = 400 nm), K414V (1,25D = 25 nm; MK = 250 nm), V418A (1,25D = 75 nm; MK = 750 nm), V418L (1,25D = 1 nm; MK = 10 nm), L404V/V418L (1,25D = 500 nm; MK = 5 mm), L404V/L414V (1,25D = 75 nm; MK = 750 nm), and L404F/V418L (1,25D = 10 nm; MK = 100 nm). *, measured reporter activity is significantly reduced when compared with the 1,25D-induced SEAP-reporter activity in the given construct (p < 0.01; n ≥ 3, ±S.E.). **, SEAP-reporter activity is significantly reduced when compared with both the 1,25D-hVDRwt and 1,25D+MK·hVDRwt experiments (p < 0.05, ±S.E.; #, p < 0.01, ±S.E.).

hVDR-His-305 and/or His-397 Mutations Alter 1,25D Agonist Potential and hVDR Binding Affinity

Located opposite the helix-3/helix-12 interface in the hVDR LBP are the basic His-305 and His-397 residues (Fig. 2). To study the effect that expanding or shrinking the hVDR LBP molecular volume at the 305 and 397 loci has on 1,25D agonist potential, H305F, H305A, H397F, H305A/H397F, and H305F/H397F mutants were assayed. Of these mutants, the H305A, H397F, and H305A/H397F modifications increased the free volume of the LBP and had a weakened ability to respond to 1,25D (Table 2). However, only the H305A and H305A/H397F mutants were nearly as effective in attenuating 1,25D-induced transactivation when compared with the helix-3/helix-12 interface mutants (compare Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 2.

VDR LBP molecular volume, 1,25D/MK EC50 values, and VDR affinity in the His-305 and/or His-397 point mutants

The LBP molecular volumes were calculated using DS 2.0 (see “Experimental Procedures”). 1,25D and MK EC50 values were measured in CV cells co-transfected with a SEAP-reporter plasmid and listed VDR construct. All 1,25D EC50 values are statistically (p ≤ 0.05) greater than hVDRwt with the exception of H305F and H305F/H397F. The MK EC50 values in H305F and H305F/H397F are statistically (p ≤ 0.01) less than the 1,25D/MK EC50 in hVDRwt and 1,25Ds EC50 in the given mutant. ND indicates that this value was not determined. See supplemental Figs. 1 and 2 for sample 1,25D and MK dose-response curves obtained in these mutants. The relative competitive index values indicate how well MK competes off 0.05 pmol of [3H]1,25D in a recombinant hVDR LBD (aa 118–427, Δ165–215) clarified extract. All studies incorporate a HAP workup protocol (31) to separate bound ligand from free. 1.25D and MK inhibitory concentrations (IC50, half of [3H]1,25D competed off) were determined in the recombinant hVDR LBD. These values indicate what concentration of MK or 1,25D is required to compete off 50% of the [3H]1,25D. The HAP protocol was used to separate bound from free in these experiments. The IC50 curves are provided in supplemental Fig. 3.

| Construct | LBP molecular volume | 1,25D EC50 | MK EC50 | MK relative competitive index | 1,25D IC50 | MK IC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Å3 | nm | nm | nm | nm | ||

| xhVDRwt | 406 | 1.4 ± 0.15 (n = 20) | >500 (n = 6) | 10.6 ± 5.3 (n = 6) | 5.21 ± 2.79 (n = 4) | 37.9 ± 8.14 (n = 4) |

| H305F | 392 | 3.2 ± 0.93 (n = 3) | 0.062 ± 0.001 (n = 3) | 26.1 ± 23.2 (n = 4) | 17.0 ± 2.74 (n = 4) | 15.8 ± 9.63 (n = 4) |

| H397F | 421 | 9.1 ± 1.3 (n = 6) | ∼100 (n = 2) | ND | ND | ND |

| H305A | 461 | 25.0 ± 2.9 (n = 6) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| H305A/H397F | 460 | 31.0 ± 10.0 (n = 7) | >500 (n = 3) | ND | ND | ND |

| H305F/H397F | 365 | 1.6 ± 0.13 (n = 4) | 0.054 ± 0.035 (n = 3) | 227 ± 136 (n = 4) | 85.4 ± 36.9 (n = 4) | 73.5 ± 12.0 (n = 4) |

In contrast, the H305F and H305F/H397F mutations reduced the free volume of the hVDR LBP and showed an hVDRwt-like response to 1,25D (Table 2). This functional result correlated well with the measured affinity of 1,25D in H305F, but not H305F/H397F, where the ability of 1,25D to bind the H305F/H397F was weakened by ∼15-fold (Table 2).

MK·hVDR Antagonist/Agonist Activities Are Significantly Altered by the His-305 and/or His-397-hVDR Mutations

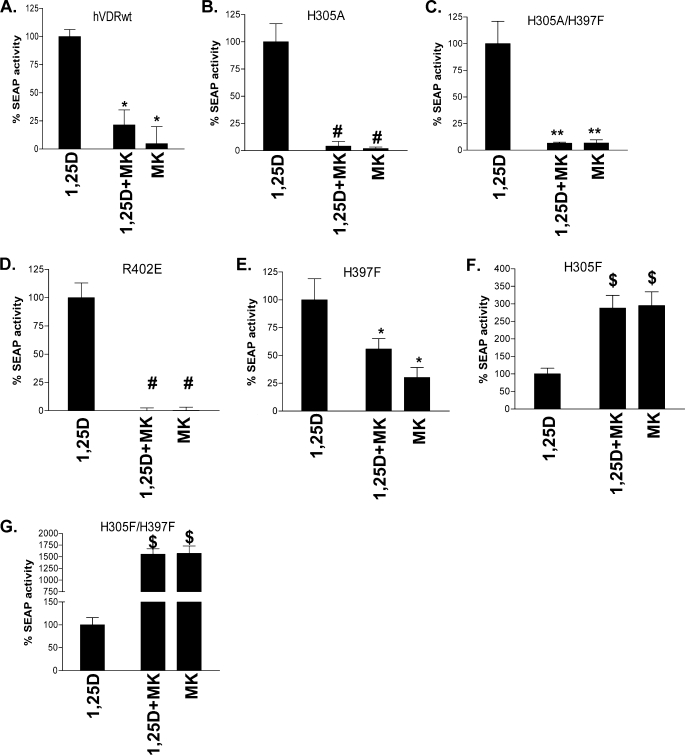

When the H305A and H305A/H397F mutants were co-incubated with an EC50 dose of 1,25D and a 10-fold excess of MK, MK functioned as a complete antagonist (≤5% of the 1,25D-reporter activity (Fig. 4, A–C). MK also functioned as a complete antagonist in the R402E hVDR construct, which has been previously shown to intrinsically reduce the stability of the closed hVDR helix-12 conformation (20) (Fig. 4D). The only mutant that increased the free molecular volume of the hVDR LBP that did not adhere to the enhanced antagonistic trend of MK was H397F (Fig. 4E).

FIGURE 4.

Switching of MK into a complete antagonist/superagonist. CV1 cells were co-transfected with the osteocalcin VDR element-driven SEAP reporter and hVDRwt, H305A, H305A/H397F, H305F, H397F, or H305F/H397F plasmid constructs. A, compares the agonist potential of the EC50 dose of 1,25D alone (see Table 2), in the presence of a 10-fold excess of MK (1,25D + MK) and 10× MK alone in hVDRwt (n = 20). B–G depict the results obtained when CV1 cells were transfected with H305A, H305A/H397F, R402E, H397F, H305F, and H305F/H397F mutant constructs (n ≥ 3). The ligand concentrations were as follows: hVDRwt (1,25D = 1 nm; MK = 10 nm), H305A (1,25D = 30 nm; MK = 300 nm), H305A/H397F (1,25D = 30 nm; MK = 300 nm), R402E (1,25D = 10 nm; MK = 100 nm), H305F (1,25D = 1 nm; MK = 10 nm), H305F/H397F (1,25D = 1 nm; MK = 10 nm), and H397F (1,25D = 10 nm; MK = 100 nm). *, measured reporter activity is significantly reduced when compared with the 1,25D-induced SEAP-reporter activity in the given construct (p < 0.01; n ≥ 3, ±S.E.). **, SEAP-reporter activity is significantly reduced when compared with both the 1,25D-hVDRwt and 1,25D+MK·hVDRwt experiments (p < 0.05, ±S.E.; #, p < 0.01, ±S.E.). $, 1,25D + MK or MK agonist response is significantly better than the 1,25D SEAP-reporter induction in the same construct (p < 0.01, ±S.E.). Representative 1,25D and MK dose-response curves in these mutants are presented in supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

Surprisingly, MK antagonism was lost in the H305F and H305F/H397F hVDR mutant constructs (Fig. 4, F and G, respectively). In fact, MK was a 29- and 33-fold more efficient agonist than 1,25D and therefore showed a superagonist response in these mutants (Table 2, 4th column). MK's efficacy (i.e. EC50) with H305F and H305F/H397F were the same; however, the agonist potency of 10 nm MK was approximately five orders of magnitude better in the H305F/H397F construct (Fig. 4G). These results indicate that reducing the free molecular volume of the hVDR LBP provides a physicochemical environment capable of overcoming the reduced molecular volume of the MK side chain (Fig. 1).

Given that the MK side chain has more π-bond character when compared with 1,25D, we tested if the switch of MK into a superagonist was due to the H305F modification increasing MK's VDR affinity. The measured MK-VDR affinity (i.e. IC50) in H305F and H305F/H397F indicated that it was only slightly better in the H305F construct and worse in the H305F/H397F construct when compared with the MK·hVDRwt affinity (Table 2). Thus the measured MK-H305F/H397F EC50 and IC50 values do not correlate, an observation that was also true for 1,25D (Table 2). Because a correlation between affinity and function did not exist, we next determined if MK is capable of stabilizing the transcriptionally active, closed helix-12 conformation in H305F and H305F/H397F by performing partial trypsin digest (i.e. PSA) experiments.

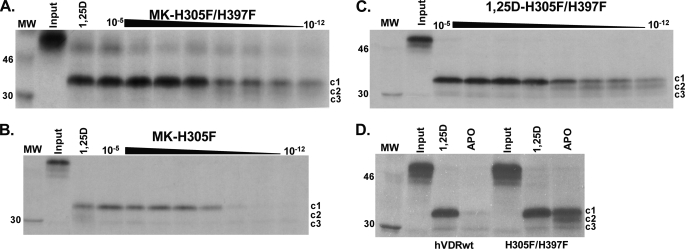

MK Stabilizes the Active, Closed hVDR Helix-12 Conformation (hVDR-c1) in the H305F and H305F/H397F Constructs

Three major hVDR fragments were generated by PSA. The ∼34-kDa hVDRwt fragment stabilized by 1,25D represents the active, closed conformation of helix-12 (hVDR-c1, Fig. 5A) (20, 30). The MK-H305F and MK-H305F/H397F PSA results demonstrated that MK did stabilize a strong hVDR-c1 band (Fig. 5, A and B). Furthermore, the hVDR-c1 band was observed at very low doses of MK only in the H305F/H397F construct (Fig. 5, compare A and B). The hVDR-c1 band was also observed at low doses of 1,25D (Fig. 5C) indicating that the enhanced stability of the hVDR-c1 conformer stems from a favorable intramolecular effect introduced by the H305F/H397F double mutation. This was confirmed by a significant enhancement in the protection of the apo-H305F/H397F construct against proteolytic degradation when compared with apo-hVDRwt (Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 5.

1,25D and MK stabilize the hVDR closed conformation (hVDR-c1) in the H305F and H305F/H397F constructs. A–C depict the H305F/H397F and H305F trypsin fragments stabilized by MK and 1,25D (15% SDS-PAGE gels). In A and B the lane labeled 1,25D shows the PSA footprint stabilized by 10−5 m. Each gel represents an MK dose curve from 10 μm to 1 pm. Within the lanes in all panels, the hVDR-c1 (∼34 kDa, aa 174–427), -c2 (∼32 kDa, aa 174–413), and -c3 (∼30 kDa, aa 174–402) are labeled (20). D, 15% SDS-PAGE PSA footprint for apo/holo-hVDRwt and H305F/H397F. The concentration of 1,25D used in the holo-hVDR experiments was 10−5 m. For the MK-H305A, H397F, and H305A/H397F PSA footprint see supplemental Fig. 4.

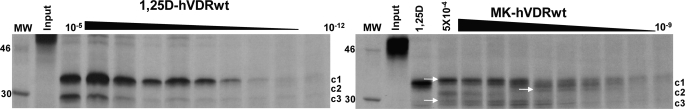

Formation of MK·hVDRwt Covalent Adducts

Consistent with the proposal that the MK molecule can form a covalent adduct with the hVDR LBP (10), the MK·hVDRwt PSA dose experiment demonstrated that the c1, c2, and c3 can be covalently modified by MK in a dose-dependent manner (see white arrows, Fig. 6). The covalent adducts were not observed in any of the His-305 or His-397 point mutations, as determined by PSA (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. 4), suggesting that either His residue is capable of forming an MK covalent adduct. To test the validity of this hypothesis and to gain a more precise structural/molecular understanding for the switch of MK into a superagonist/complete antagonist and its known species specificity (7, 10), we developed a flexible docking molecular modeling protocol.

FIGURE 6.

Evidence MK forms covalent adducts with hVDRwt. Representative 12.5% SDS-PAGE gels showing the 1,25D (10 μm to 1 pm) and MK (1 μm to 1 nm) dose PSA results in hVDRwt, and the lane labeled 1,25D shows the PSA footprint stabilized by 10−5 m. The hVDR-c1 (∼34 kDa, aa 174–427), -c2 (∼32 kDa, aa 174–413), and -c3 (∼30 kDa, aa 174–402) are labeled (20). In the MK·hVDRwt gel (right panel) white arrows highlight what are concluded to be covalent adducts of c1, c2, and c3 formed by MK based on molecular weight shifts (see “Experimental Procedures”).

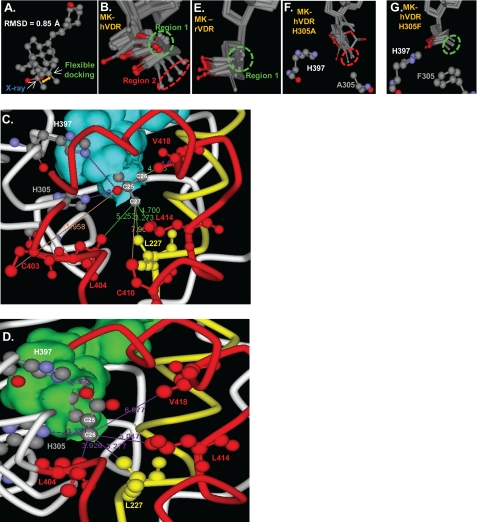

Simulating the Dynamics and Energetic Stability of the 1,25D·hVDR Complex

To simulate the binding and stability of flexible vitamin D sterols to a flexible hVDR LBP we combined two techniques. Whole molecule PC_Model GMMX conformational search calculations were employed to generate conformational isomers of 1,25D and MK. For 1,25D this computation produced 502 conformational isomers and for MK 133, consistent with the reduction in the rotational degrees of freedom of the MK side chain (Fig. 1). The conformational isomers were then docked to different hVDR LBP conformers using the flexible docking protocol of Discovery Studio 2.0 (DS2.0, see “Experimental Procedures”).

Using this approach, the 1,25D conformational isomer observed in the x-ray structure was selected as the most energetically favored ligand pose in the flexible hVDR LBP (Fig. 7A). The ΔGbinding value calculated for the energy optimized 1,25D-hVDR x-ray complex was −47.1 kcal/mole, whereas the complex predicted by the flexible docking protocol was −50.7 kcal/mole (Table 3), indicating a minor refinement to the x-ray complex. Furthermore, the 1,25D ΔGbinding values calculated for H305F, H305F/H397F, H397F, and H305A qualitatively correlated with the measured 1,25D EC50 values in these mutants (Table 2).

FIGURE 7.

1,25D/MK·hVDR flexible docking results. A, superimposition of the 1,25D molecules extracted from the x-ray complex (25) and the lowest energy (ΔGbinding) flexible docking complex. The all atom root mean square deviation of 1,25D was 0.850 Å. Superimposition of the VDR Cα atoms of the same two complexes produced a root mean square deviation of 0.618 Å; all VDR backbone atoms were 0.635 Å; all VDR side-chain atoms were 0.956 Å. B, molecular overlay of the top 10 MK·hVDR LBP flexible docking complexes, depicting the two distinct MK side-chain conformational isomers observed in these complexes (Region 1, green dashed circle; Region 2, red dashed circle). C, the intermolecular interactions made between the 25-OH group and the C26 and C27 atoms of 1,25D observed in the lowest energy flexible docking complex (ΔGbinding). The VDR helix 11/helix-12 residues (Cys-403, Leu-404, Cys-410, Leu-414, and Val-418) are shown in red, and the helix-3, Leu-227 residue is shown in yellow. The same color scheme is used in panel D. The closest van der Waals (vdW) distance between Leu-227 (3.27 Å), Cys-403 (11.96 Å), Leu-404 (5.25 Å), Cys-410 (7.96 Å), Leu-414 (4.70 Å), Val-418 (4.03 Å), and the C26 or C27 terminal methyl groups of the 1,25D side-chain atoms are indicated by solid lines. The overlay of the top 10 1,25D-hVDRwt flexible docking complexes is presented in supplemental Fig. 5. D, the MK·hVDR LBP Region 2 complex and the intermolecular vdW interactions formed between the lactone C26 atom (Fig. 1) and Leu-227 (3.28 Å), His-305 (3.32 Å), His-397 (2.93 Å, to lactone ring oxygen), Leu-404 (3.93 Å), Leu-414 (5.05 Å), and Val-418 (6.98 Å) residues. These contacts are highlighted by purple lines. Importantly, the C26 atom of MK (Fig. 1) lies perpendicular to the sp2-hybrid imidazole nitrogen atom of His-305 in this complex, a good molecular geometry for formation of a covalent adduct (supplemental Fig. 6). E, the top 10 MK rodent VDR (rVDR) LBP flexible docking complexes indicate an enhanced selectivity for the MK side chain to localize in Region 1. To view the vdW interactions formed between the lactone of MK and the two His residues in the rVDR complex see supplemental Fig. 7. F, overlay of the top 10 H305A LBP flexible docking complexes. In all of these complexes the MK side chain occupies Region 2 of LBP, indicated by the red dashed circle. G, overlay of the top 10 MK-H305F LBP flexible docking complexes, indicating the C26 atom of MK that exclusively occupies Region 1 (green circle).

TABLE 3.

1,25D and MK flexible docking results

Calculations were performed with the hVDR LBD (aa 118–427, Δ165–215) and ligand conformations generated using PC_Model v8.0 (see “Experimental Procedures”). The statistical distribution of the MK side-chain lactone in the VDR LBP regions 1–3 is provided for the top 10 complexes. The ΔG of binding (kilocalories/mol) values were calculated for the top five complexes in each flexible docking calculation using the Generalized Born with Molecular Volume method (see “Experimental Procedures”).

| hVDR construct | Avg. 1,25D ΔGbinding | hVDR construct | MK region 1:Region 2: Region 3 | Avg. MK ΔGbinding, all regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hVDRwt | −50.7 | hVDRwt | 60:40:0 | −32.4 |

| H305F | −49.2 | H305F | 100:0:0 | −47.2 |

| H305F/H397F | −51.1 | H305F/H397F | 100:0:0 | −47.4 |

| H397F | −46.3 | H397F | 20:60:20 | −51.4 |

| H305A | −39.2 | H305A | 0:100:0 | −29.4 |

Structural/Molecular Basis for MK Antagonism

The MK·hVDRwt LBD flexible docking results indicated that its lactone ring binds stably in two different regions within the hVDRwt LBP (Fig. 7B). In the Region 1 pose the terminal C26 MK side-chain atom lies close to the helix-3/helix-12 interface residues Leu-227 (4.56 Å)/Leu-414 (5.01 Å)/Val-418 (4.03 Å) and away from Leu-404 (6.02 Å, supplemental Fig. 6). The MK C26 vdW distance from Val-418 was nearly identical to that observed in the lowest energy 1,25D-hVDRwt flexible docking complex (4.39 and 4.03 Å, Fig. 7C); therefore, indicating that when the MK side chain occupies Region 1 it can function as an agonist ligand.

In the Region 2 MK·hVDRwt complex the C26 atom lies closer to Leu-227 (3.27 Å)/Leu-404 (helix 11, 3.93 Å) and away from the helix-12 residues Leu-414 (5.05 Å)/Val-418 (6.98 Å, helix-12 residues, Fig. 7D). This indicates that, when the MK side chain is bound to the LBP in the Region 2 orientation, MK functions as an antagonist. Importantly, the MK side-chain heterogeneity within the LBP was not observed when the same set of MK conformational isomers were flexibly docked to the rodent VDR (rVDRwt) LBP using an identical flexible docking protocol (Fig. 7E).

The average calculated ΔGbinding values for the top five Region 1 and 2 MK·hVDR LBP complexes indicate that MK affinity for hVDR is significantly stronger when the side chain occupies Region 2 (−25.4 versus −39.3 kcal/mole, respectively, Table 3). This computational result correlated well with the fact that MK functioned as an antagonist ligand in the hVDRwt construct (Figs. 3 and 4A). Furthermore, when the MK side chain was bound to Region 2 of the LBP, an approach to the formation of an MK-C26/His-305 covalent adduct (3.32 Å) could be observed (Fig. 7D).

Structural/Molecular Basis for MK Complete Antagonism

The H305A mutation substantially increased the free volume of the LBP opposite the helix-3/helix-12 interface. Therefore, the average distance between the MK C26 atom and Leu-414 (5.34 Å) and Val-418 (7.08 Å) in the H305A LBP was significantly increased when compared with those same measurements in hVDRwt (4.58 and 5.89 Å, supplemental Table 1). This was due to the side-chain lactone exclusively occupying Region 2 of the H305A LBP (Fig. 7F and Table 3). These same trends were observed in the H305A/H397F flexible docking results (supplemental Table 1).

Structural/Molecular Basis for MK Superagonism

The MK-H305F flexible docking results indicate a shift of the MK C26 atom to exclusively occupy Region 1 of the H305F LBP (Table 3 and Fig. 7G). A concomitant increase in MK affinity was also observed (−47.2 kcal/mole, Table 3). The increased stability of this complex was imparted by a π-π overlap between Phe-305 and the MK side-chain lactone (supplemental Fig. 7). These same trends were observed in the H305F/H397F LBP flexible docking results (−47.4 kcal/mol, Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This communication shows that MK antagonism of the 1,25D-hVDRwt genomic response is unique when compared with the traditional mode of NR antagonism. This is due to the reduced side-chain molecular volume of MK when compared with 1,25D and its unique side-chain chemistry (Fig. 1). We demonstrated using traditional structure-function analyses and molecular modeling that the reduced molecular volume allows for heterogeneity in the MK side-chain conformations accepted by the hVDRwt LBP, when compared with 1,25D (Regions 1 and 2, see Fig. 7, A and B). To our knowledge the flexible docking protocol used to generate this hypothesis is the first simulation that lacks bias in the conformation and placement of the ligand within the VDR LBP (7, 30, 32). Importantly, the average 1,25D/MK·hVDRwt ΔGbinding values (Table 3) qualitatively support the fact that a 10-fold excess of MK is required to be an efficient 1,25D-hVDR antagonist (Figs. 3 and 4A and Table 2) (16).

According to our 1,25D/MK·hVDRwt flexible docking results the MK·hVDRwt Region 2 complex is energetically favored (Table 3) and represents a good antagonist pose within the hVDR LBP. This hypothesis is based on the observation that important vdW contacts with the Leu-414 and Val-418 helix-12 residues were absent when MK bound with Region 2 of the VDR LBP (Fig. 7D). So when bound to Region 2, MK was incapable of efficiently anchoring helix-12 in the transcriptionally active, closed conformation (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

The VDR helix-12 conformational ensemble. Helix-12 of the VDR molecule is intrinsically disordered in the absence of ligand. In this figure the dynamic conformational heterogeneity of helix-12 of the hVDR is projected using NR x-ray data (see Protein Data Bank). It is observed that in hVDR-c1, helix-12 (black ribbon, labeled H12) is in the closed, active conformation (i.e. identical to its position in Fig. 2). It is proposed that, in the hVDR-c2 conformational isomer, helix-12 (black ribbon, labeled H12) is bound to the NCoA surface (Fig. 2) and is known to be induced by the antagonist analog ZK (Fig. 1) (5). It is proposed that in hVDR-c3, helix-12 (black ribbon, labeled H12) takes on an opened conformation, where the ligand binding pocket is accessible to ligand (bottom, hVDR-c3 structure) or is occupied by helix-11 residues (orange ribbon in the top hVDR-c3 structure), thereby exposing the C-terminal helix-11 Arg-402 residue (20).

This hypothesis is consistent with the antagonist potency of MK being increased by the helix-3/helix-12 interface and H305A mutants (Figs. 3, 4B, and 4C). All of these mutations increase the free molecular volume of the VDR LBP and exacerbate the intrinsic mobility of helix-12. In the H305A LBP in particular, the MK side chain was shown to exclusively bind to Region 2 of the VDR LBP (Table 3 and Fig. 7F).

Furthermore, the MK·hVDRwt Region 2 complex is consistent with the formation of an MK·hVDRwt covalent adduct. However, our results suggest the adduct was formed with His-305 (Fig. 6) rather than Cys-403 or Cys-410, as previously proposed (see supplemental Fig. 6) (10). Importantly, the MK-His-305 adduct could only be formed when the MK side chain occupied Region 2 of the hVDR LBP; therefore, increasing the half-life of the antagonist pose of MK (Fig. 7D). Thus our comprehensive structure-function analyses provide a detailed molecular understanding underlying the augmented ability of the MK·hVDRwt complex to recruit nuclear co-activator (NCoA) proteins (32).

The flexible docking results also provide a rationale for how MK can function as a partial agonist (7, 10) or superagonist (Fig. 4, F and G). When bound to the VDR LBP in Region 1, the C26 atom of MK formed vdW contacts with Leu-227, Leu-414, and Val-418. Therefore, MK makes vdW interactions with the helix-3/helix-12 interface residues in Region 1 and explains why MK is not a complete antagonist in hVDRwt (Figs. 2 and 4A) (7, 10, 16).

This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that in the H305F and H305F/H397F LBPs the MK side chain favors binding to Region 1 (Fig. 7G). Furthermore, in these VDR constructs, MK showed the ability to efficiently stabilize hVDR-c1 (Fig. 5). These two results, coupled with the calculations indicating MKs affinity is increased in the H305F and H305F/H397F constructs (Table 3) provide a rationale explanation for how MK is converted into a superagonist ligand (Fig. 4, F and G). Thus the models (Table 3 and Fig. 7) seem to be more consistent with the MK structure (PSA, Figs. 5 and 6) and function (EC50, Fig. 4) results than are the IC50 values (Table 2). This is likely due to the dynamics and complexity of ligand binding to the hVDR molecule being much more complex then that inferred by a traditional NR induced-fit model (19).

To our knowledge the switch of a known antagonist into a superagonist by the introduction of a conservative mutation is a novel finding in the NR field. Importantly, the measured MK EC50 values in the His-305 and H305F/H397F mutants are parallel or better to those reported for historic hVDRwt superagonists (11, 33).

We have previously demonstrated that the VDR molecule exists as an ensemble of conformational states, subject to a population distribution change, induced by ligand binding and/or mutation (Fig. 8) (18–21). The apo-H305F/H397F PSA results demonstrated that the population distribution VDR ensemble members can be altered by subtle changes in the VDR primary sequence. The switch of Cys-403 and Cys-410 of the hVDR to Ser and Asn, respectively, in the rodent VDR (rVDR) has a similar effect, in that the intramolecular stability of the closed helix-12 conformation is enhanced (7, 20) (supplemental Fig. 9). Thus when coupled to the observation that the MK side chain favors Region 1 when flexibly docked to the rodent (rVDR) LBP (Fig. 7E), the inability of MK to form a covalent adduct with the rVDR (10) and MK's species specificity can be understood.

Viewing the VDR or helix-12 as a molecular ensemble (Fig. 8) (18–21) also provides an explanation for how 1,25D can function to activate transcription as efficiently in the H305F/H397F construct as was observed in hVDRwt, despite a significant reduction in its binding affinity (Table 2). The same intramolecular effect also provides an explanation for why MK showed greater potency in the H305F/H397F construct relative to H305F (Fig. 4, F and G). In closing, the evidence that the H305F/H397F double mutation can dramatically alter the population distribution of helix-12 ensemble members indicates that it may be possible to engineer a constitutively active hVDR construct.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–9 and Table 1.

- 1,25D

- 1α,25(OH)2-vitamin D3

- VDR

- vitamin D receptor

- NCoA

- nuclear co-activator

- LBD

- ligand binding domain

- LBP

- ligand binding pocket

- NR

- nuclear receptor

- ZK

- ZK159222

- rVDR

- rodent VDR

- hVDR

- human VDR

- vdW

- van der Waals

- PSA

- protease sensitivity assay

- GMMX

- global-MMX

- SEAP

- secreted alkaline phosphatase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sutton A. L., MacDonald P. N. (2003) Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 777–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheskis B., Freedman L. P. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 3329–3338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barletta F., Freedman L. P., Christakos S. (2002) Mol. Endocrinol. 16, 301–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rachez C., Freedman L. P. (2000) Gene 246, 9–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tocchini-Valentini G., Rochel N., Wurtz J. M., Moras D. (2004) J. Med. Chem. 47, 1956–1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toell A., Gonzalez M. M., Ruf D., Steinmeyer A., Ishizuka S., Carlberg C. (2001) Mol. Pharmacol. 59, 1478–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peräkylä M., Molnár F., Carlberg C. (2004) Chem. Biol. 11, 1147–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egea P. F., Klaholz B. P., Moras D. (2000) FEBS Lett. 476, 62–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brzozowski A. M., Pike A. C., Dauter Z., Hubbard R. E., Bonn T., Engström O., Ohman L., Greene G. L., Gustafsson J. A., Carlquist M. (1997) Nature 389, 753–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ochiai E., Miura D., Eguchi H., Ohara S., Takenouchi K., Azuma Y., Kamimura T., Norman A. W., Ishizuka S. (2005) Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 1147–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siu-Caldera M. L., Sekimoto H., Peleg S., Nguyen C., Kissmeyer A. M., Binderup L., Weiskopf A., Vouros P., Uskokoviæ M., Reddy G. S. (1999) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 71, 111–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishizuka S., Kurihara N., Reddy S. V., Cornish J., Cundy T., Roodman G. D. (2005) Endocrinology 146, 2023–2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miura D., Manabe K., Ozono K., Saito M., Gao Q., Norman A. W., Ishizuka S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 16392–16399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishizuka S., Miura D., Ozono K., Saito M., Eguchi H., Chokki M., Norman A. W. (2001) Steroids 66, 227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miura D., Manabe K., Gao Q., Norman A. W., Ishizuka S. (1999) FEBS Lett. 460, 297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bula C. M., Bishop J. E., Ishizuka S., Norman A. W. (2000) Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1788–1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takenouchi K., Sogawa R., Manabe K., Saitoh H., Gao Q., Miura D., Ishizuka S. (2004) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 89–90, 31–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norman A. W., Mizwicki M. T., Norman D. P. G. (2004) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 27–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizwicki M. T., Norman A. W. (2009) Sci. Signal. 2, re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizwicki M. T., Bula C. M., Bishop J. E., Norman A. W. (2007) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 103, 243–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizwicki M. T., Keidel D., Bula C. M., Bishop J. E., Zanello L. P., Wurtz J. M., Moras D., Norman A. W. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12876–12881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bula C. M., Huhtakangas J., Olivera C., Bishop J. E., Norman A. W., Henry H. L. (2005) Endocrinology 146, 5581–5586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Im W., Lee M. S., Brooks C. L., 3rd (2003) J. Comput. Chem. 24, 1691–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zoete V., Meuwly M., Karplus M. (2005) Proteins 61, 79–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rochel N., Wurtz J. M., Mitschler A., Klaholz B., Moras D. (2000) Mol. Cell 5, 173–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciesielski F., Rochel N., Mitschler A., Kouzmenko A., Moras D. (2004) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 89–90, 55–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tocchini-Valentini G., Rochel N., Wurtz J. M., Mitschler A., Moras D. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5491–5496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Väisänen S., Ryhänen S., Saarela J. T., Peräkylä M., Andersin T., Mäenpää P. H. (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 62, 788–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi M., Yamamoto K., Masuno H., Nakashima K., Taga T., Yamada S. (2001) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9, 1721–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peleg S., Sastry M., Collins E. D., Bishop J. E., Norman A. W. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 10551–10558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wecksler W. R., Norman A. W. (1979) Anal. Biochem. 92, 314–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurihara N., Ishizuka S., Demulder A., Menaa C., Roodman G. D. (2004) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 89–90, 321–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peleg S., Sastry M., Collins E. D., Bishop J. E., Norman A. W. (1994) in Vitamin D, A Pluripotent Steroid Hormone: Structural Studies, Molecular Endocrinology, and Clinical Applications (Norman A. W., Bouillon R., Thomasset M. eds) pp. 237–238, Walter DeGruyter, Berlin [Google Scholar]