Abstract

Src family kinase (SFK) activity is elevated in many human tumors, including breast cancer, and is often associated with aggressive disease. We examined the effects of SKI-606 (bosutinib), a selective SFK inhibitor, on human cancer cells derived from breast cancer patients in order to assess its potential for breast cancer treatment. Our results show that SKI-606 caused a decrease in cell motility and invasion of breast cancer cell lines with an IC50 of ~250 nM, which was also the IC50 for inhibition of c-Src kinase activity in intact tumor cells. These changes were accompanied by an increase in cell-to-cell adhesion and membrane localization of beta-catenin. By contrast, cell proliferation and survival were unaffected by SKI-606 at concentrations sufficient to block cell migration and invasion. Analysis of downstream effectors of Src revealed that SKI-606 inhibits the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) and Crk-associated substrate (p130Cas) with an IC50 similar to inhibition of c-Src kinase. Our findings indicate that SKI-606 inhibits signaling pathways involved in controlling tumor cell motility and invasion, suggesting that SKI-606 is a promising therapeutic for breast cancer.

Keywords: Src kinase, SKI-606, human breast cancer, migration, invasion

Introduction

The cellular Src (c-Src) protein is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase normally maintained in an inactive conformation via intramolecular interactions. When acted upon by upstream signals, such as growth factors, c-Src undergoes a conformational change resulting in activation of its kinase (1, 2). Importantly, c-Src coordinates multiple signaling pathways known to be involved in tumor progression such as proliferation, survival, motility, angiogenesis, cell-cell communication, adhesion, and invasion (3, 4). Therefore, c-Src is a potential molecular target for therapy of human neoplasias, including breast cancer. The recent introduction of Src family kinase (SFK) inhibitors in clinical trials for solid tumors necessitates a better understanding of their mechanism of action in order to optimize their clinical effectiveness in patients.

Early studies reported elevated levels of c-Src tyrosine kinase activity in breast cancer samples when compared to normal tissue (5). These findings were substantiated using immunohistochemistry, in vitro kinase assays, and Western blot analyses (6–8). Previously, we have demonstrated that Src is significantly activated in invasive carcinoma compared to paired non-neoplastic parenchyma from 45 patients with stage II breast cancer (P<0.001) (9). The mechanisms underlying Src kinase activation in breast cancer are not fully elucidated yet but evidence points to the overexpression or altered activity of upstream receptors, such as EGF-R, Her2/neu, PDGF-R, FGF-R, c-Met, integrins, and steroid hormone receptors (2, 10, 11). Elevated levels of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) may also contribute to high c-Src kinase activity in breast cancer by dephosphorylating c-Src on its negative regulatory domain (12).

Multiple studies using various Src kinase inhibitors and dominant-negative mutants support the finding that inhibiting c-Src activity in a variety of tumor sites blocks cell proliferation, induces apoptosis, and decreases metastatic potential, thereby implicating c-Src as an attractive molecular target for anti-cancer therapy (13–16). Given the poor survival rates of patients with distant breast cancer metastases (17) and the association of c-Src activity with aggressive neoplastic behavior, development of Src inhibitors for cancer treatment is of considerable interest. SKI-606 (bosutinib) is a potent, orally bioavailable, dual Src/Abl kinase inhibitor previously shown to have antiproliferative effects in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells, to inhibit colon tumor cell colony formation in soft agar, and to suppress tumor growth in K562 and colon tumor cell xenograft models (18, 19).

We report here that in human cancer cells derived from breast cancer patients, SKI-606 preferentially inhibits cell spreading, migration and invasion, while leading to stabilized cell-to-cell adhesions and membrane localization of beta-catenin. These effects are not associated with changes in proliferation or survival and are accompanied by inhibition of the Src/FAK/p130Cas signaling pathway. Taken together, our data point to SKI-606 as a promising anti-invasive and anti-metastatic drug for the potential treatment of breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

All human cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-468, MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, MDA-MB-435s (isolated from a breast cancer patient yet melanoma-derived)) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA) and cultured following ATCC protocols. Src, Yes and Fyn knockout mouse embryo fibroblasts (SYF−/−) and SYF−/− cells with c-Src reintroduced (SYF-Src) were also obtained from the ATCC. A 10 mM stock of SKI-606 (Wyeth, Madison, NJ) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was diluted to the desired concentrations in culture medium prior to treatment. When exceeding 48 h treatment periods, redosing was scheduled every 2 days. The DMSO control was used at 0.01% or 0.0025%, to correspond to the highest SKI-606 concentration used for each experiment.

Migration assay and video time-lapse microscopy (VTLM)

Uniform “wounds” were made using a pipette tip on confluent monolayers of cells grown in 24-well plates or T-25 flasks (for VTLM), followed by immediate addition of the vehicle control (0.01% DMSO) or 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3 and 1µM SKI-606 as indicated. Cells were allowed to migrate into the denuded area for 48 h, then fixed and stained with a coomassie blue solution (20). Photomicrographs were acquired with a 4x objective under brightfield illumination using a CCD camera-mounted Olympus IX81 Inverted microscope (Center Valley, PA), and analyzed with Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). For VTLM, flasks were gassed with 5% CO2 and placed at 37°C for immediate imaging using 4x or 10x objectives from identically equipped Nikon TS100 Phase microscopes (Nikon, Melville, NY) coupled to Sanyo video CCD cameras (Sanyo, Chatsworth, CA) and digitized at 640×480 pixels with a Matrox frame grabber board (Matrox, Quebec, Canada). Photomicrographs were captured every 2 min for each flask simultaneously for a total of 50 h. ImageJ version 1.36b (NIH, Bethesda, MD) was used to process the images and the speed of migration was assessed using Image-Pro Plus software.

Invasion assay

24-well cell invasion chambers (Becton Dickinson) were used in accordance with the supplier’s instructions. Cells (human and mouse) were suspended in 500 µl serum-free medium and treated with SKI-606 (250 nM or 1 µM) or the vehicle control DMSO (0.0025% or 0.01%) and were loaded into each upper invasion chamber. Cells were allowed to invade towards a lower chamber containing 750 µl of freshly-collected conditioned medium from each respective cell line for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Non-invasive cells were removed with PBS from the upper chamber and the remaining invasive cells stained using the Diff-Quik Stain kit (Dade Behring, Newark, DE). The percent reduction in the number of invaded cells in treated wells compared to vehicle control treated wells is presented.

Proliferation assay

MTS assays were performed as described by the supplier (Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, approximately 5,000 cells were seeded in each well of a 96-well plate and allowed to adhere prior to the addition of 0.01% DMSO or 0.1, 0.3 and 1µM of SKI-606. After 2–6 days incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, MTS reagent was added to each well for 30 min and absorbance measured at 490 nm.

Growth in 3D culture

Anchorage-independent growth was assessed by growing 1×105 cells in 6-well plates in a 0.33% agarose solution (Sigma, St-Louis, MO) also containing culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS, on top of a feeder layer of the same medium containing 0.7% agarose (21). Both agarose layers were supplemented with 0.01% DMSO or 1 µM of SKI-606. Photomicrographs were taken 6–10 days later under brightfield illumination. Growth on a 3D reconstituted basement membrane was performed as previously described (22). Briefly, cells were seeded on a 100% Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) basal layer containing 1 µM SKI-606 or 0.01% DMSO. A top layer of 4% Matrigel diluted in growth medium with the Src-inhibitor or vehicle control was used to overlay the cells. Clusters were allowed to grow for 4–6 days in a 37°C incubator prior to photomicrography.

Western blot analyses

Proteins were extracted using a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.1 µM aprotinin, 1 µM leupeptin, and 1 µM antipain. Fifty micrograms of cell extract were resolved on a 8% polyacrylamide-SDS gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked with 4% ovalbumin for at least 1 h, followed by an overnight incubation with the following primary antibodies: phosphorylated Src, phosphorylated Pyk2 (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA); Src (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY); phosphorylated FAK, FAK, phosphorylated p130Cas, phosphorylated Stat3, Stat3, beta-catenin, phosphorylated Akt, PARP (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). Alexa Fluor-680 conjugated secondary antibodies were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and IRDye 800 from Li-Cor (Lincoln, NE). Blots were analyzed using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were grown on a glass coverslip (1×105 cells/ml) and treated with 0.01% DMSO or 1 µM SKI-606 for 48 h prior to fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde and 10 min permeabilization in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 (PBST) at 4°C. Following three 20 min washes in PBST, cells were blocked with 0.1% BSA and 10% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1:200 anti-FAK pY576/577, 1:200 anti-FAK, 1:200 anti-beta-catenin antibodies or 1:200 anti-E-cadherin antibodies. Coverslips were washed three times in PBST followed by incubation with the appropriate secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, and staining with DAPI (0.5 ng/ml in PBS) for 15 min. Fluorescent staining was examined using a Nikon TE2000-U inverted microscope equipped with a CCD camera and photomicrographs were taken with a 40x objective and Spot Software (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

Means and standard errors are shown for all data sets. For the statistical analysis of invasion, we compared DMSO-treated cells versus SKI-606-treated cells with respect to reduction of objects invaded and used a one-sided, one-sample t-test with a hypothesized value of 0% invasion reduction representing untreated cells. We also used the Wilcoxon rank sum test as the method for comparing means in experiments where outliers violated assumptions of the traditional t-test. All experiments were repeated at least in triplicate with similar results.

Results

SKI-606 is a potent inhibitor of breast cancer cell spreading and migration

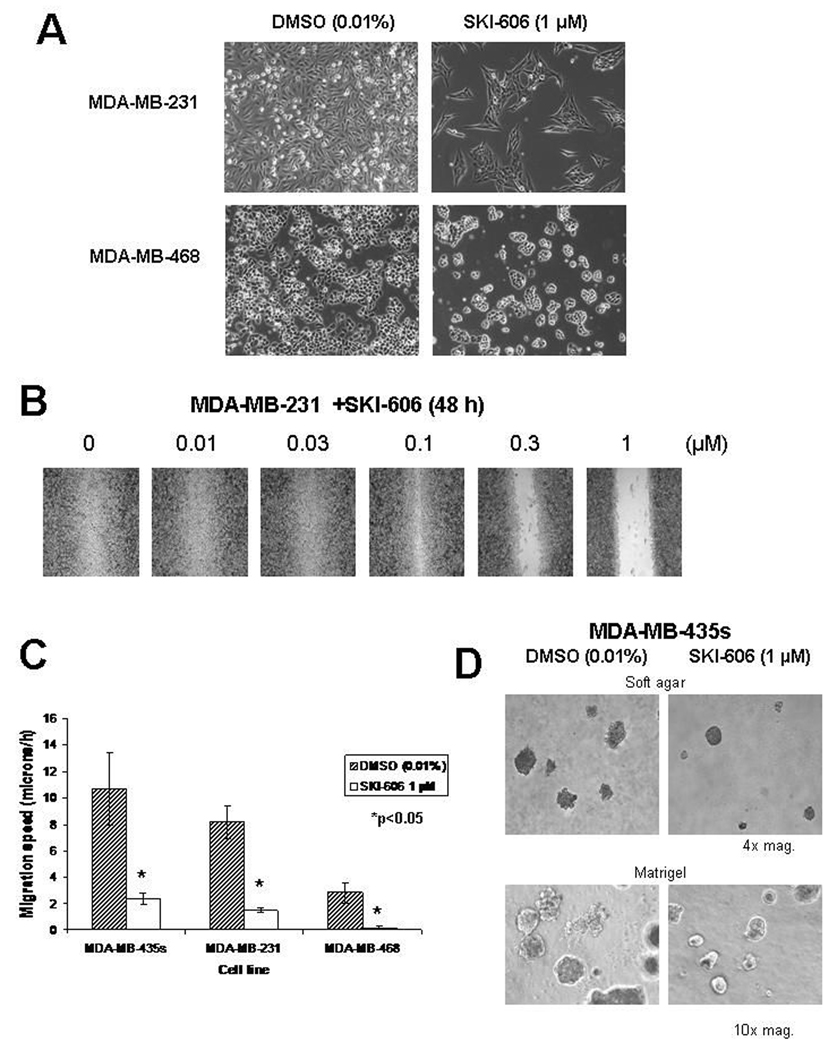

Considerable evidence points to the importance of c-Src in regulating the dynamics of cell motility and adhesion (2–4). We therefore examined the effects of a 48 h treatment with SKI-606 on cell morphology and migration in different human cancer cell lines derived from breast cancer patients. Effects on cell morphology were observed at a concentration of 1 µM SKI-606 for all cell lines examined (representative morphologies are shown in Fig. 1A), and morphological changes were apparent at concentrations as low as 0.25 µM (data not shown). SKI-606 caused the cells to adhere to each other, forming dense clusters as compared to vehicle control (DMSO) treated cells, which showed spreading over larger areas. We also examined the effects of SKI-606 on cell migration using a “wound healing” assay. Exposure to increasing concentrations of SKI-606 inhibited migration of breast cancer cell lines with IC50 values of 0.1–0.3 µM (Fig. 1B). Using video time-lapse microscopy (VTLM), we were able to quantify significant (p<0.05) inhibition of cell migration speed after treatment with 1 µM SKI-606 (Fig. 1C). Similar observations were made with cancer cells grown in soft agar or on a 3-dimensional reconstituted basement membrane; SKI-606 caused the formation of condensed aggregates with few extruding cells compared to the DMSO vehicle control treated cells (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

SKI-606 induces cell aggregation and decreases cell motility. A) MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cell lines were cultured in the presence of 1 µM SKI-606 or 0.01% DMSO control for 96 h. Photomicrographs were taken under brightfield illumination (4x magnification). B) Wound assay performed on the MDA-MB-231 cell line treated with 0, 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3 and 1µM of SKI-606 and allowed to heal for 48 h before fixation and image capture (brightfield illumination, 4x magnification). 0.01% DMSO was present in each assay well. C) Summary of migration speeds assessed via VTLM. Breast cancer cell line migration was monitored in a denuded area of a confluent cell monolayer. Speed value is shown as mean±S.E. of three independent experiments. *p<0.05 (Wilcoxon test). D) MDA-MB-435s human breast cancer cells were grown in soft agar or matrigel in the presence of 0.01% DMSO or 1 µM SKI-606 for 4–6 days and photomicrographs were taken under brightfield illumination (4x and 10x magnification).

SKI-606 blocks tumor cell invasion but not proliferation or survival

We examined the ability of breast cancer patient-derived cell lines to invade a Matrigel layer and cross a porous membrane, as a measure of invasive potential. After a 48 h treatment with 1 µM SKI-606, all the invasion-competent cell lines were unable to cross the porous membrane (data not shown), while at concentrations as low as 0.25 µM SKI-606 we observed a significant decrease in invasion potential (Fig. 2A and B). These observations indicate a similar IC50 for SKI-606-mediated inhibition of tumor cell migration and invasion. Using VTLM, we did not observe any effects of SKI-606 on cell proliferation or apoptosis associated with SKI-606 treatment over a 50 h period (supplemental VTLM data available at http://www.cityofhope.org/Researchers/JoveRichard/video). To confirm these observations, MTS assays were performed on breast cancer cell lines displaying different levels of active c-Src (23) after exposure to increasing concentrations of SKI-606. There were no significant changes in cell proliferation or viability for the cell lines examined after a 48 h treatment at concentrations exceeding the IC50 for Src inhibition (Figure 2C). Similar observations were made after treatment with up to 1 µM of SKI-606 for 4 or 6 days (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

SKI-606 inhibits cell invasion but not proliferation. A) Cells were seeded in an invasion chamber in the presence of 0.0025% DMSO vehicle control or 250 nM SKI-606 and allowed to invade the chamber towards cell-specific conditioned medium for 48 h. Photomicrographs of stained invasive cells were taken under brightfield illumination (4x magnification). B) Invasion potential of breast cancer cell lines treated with SKI-606. Values represent the % of invasive cells compared to the 0.0025% DMSO vehicle control treated cells and are shown as mean±S.E. of three independent experiments. *p<0.05 (one-sided t-test versus a 0% invasion reduction). C) Breast cancer patient-derived cell lines were assessed for proliferation upon treatment with 0.01% DMSO or 1 µM SKI-606 for 48 h using the MTS metabolic assay. Values are shown as mean±S.E. of three independent experiments, representing the % reduction in absorbance values of cells treated with SKI-606 relative to untreated cells. No statistically significant differences were observed using the Wilcoxon test. D) MDA-MB-231 cells were assessed for proliferation upon treatment with 0.01% DMSO or 0.1, 0.3, 1µM SKI-606 for 4 and 6 days using the MTS metabolic assay. Values are shown as mean±S.E. of three independent experiments, representing the % reduction in absorbance values of cells treated with SKI-606 relative to untreated cells.

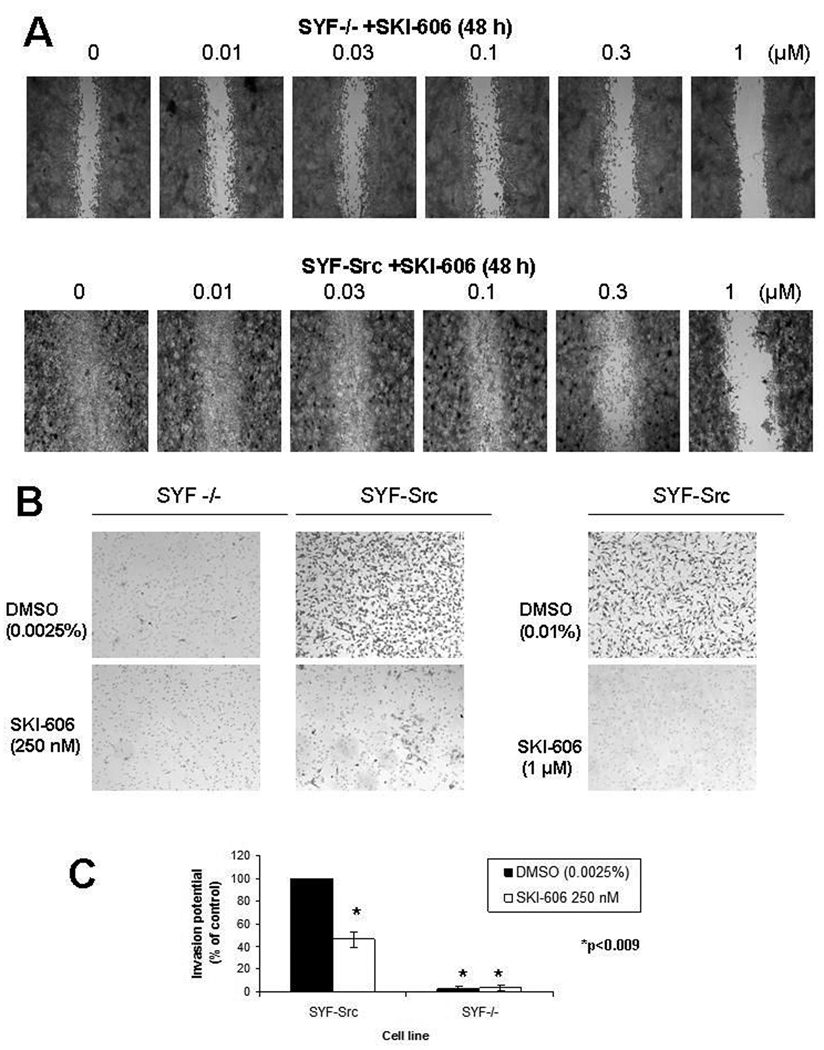

SKI-606 inhibits the invasive properties of Src, Yes and Fyn null cells with reintroduced c-Src

Src, Yes and Fyn knockout mouse embryo fibroblasts (SYF−/−), previously characterized by Klinghoffer et al. (24), provide an excellent system to determine the specificity of Src kinase inhibitors. Similar to the effects of SKI-606 on cell migration and invasion, SYF−/− cells are defective in both of these processes (Fig. 3), consistent with an essential role of Src family kinases in cell migration and invasion. We postulated that SKI-606 would have minimal effects on SYF−/− cells, while SYF−/− cells with re-introduced c-Src (SYF-Src) would exhibit restored sensitivity to SKI-606. We therefore performed a wound healing assay on SYF−/− and SYF-Src cells and compared the effects of increasing concentrations of SKI-606 on cell migration into the denuded area. After a 48 h treatment of SYF−/− cells with SKI-606, only minor effects could be visualized at 1 µM SKI-606 compared to the DMSO vehicle control (Fig. 3A). By contrast, SYF-Src cells completely covered the denuded area after 48 h, and this process was inhibited by 0.3 µM or higher concentrations of SKI-606 (Fig. 3A). When assessed for invasion potential over 48 h, SYF−/− cells were unable to cross Matrigel invasion chambers; however, SYF−/− cells with c-Src re-introduced where highly invasive unless treated with SKI-606 at concentrations of 0.25 µM or higher (Fig. 3B–C). These findings provide genetic evidence that c-Src is required for inhibition of cell migration and invasion by SKI-606.

Figure 3.

SKI-606 inhibits the invasive properties of Src, Yes and Fyn null mouse embryo fibroblasts following reintroduction of c-Src. A) Wound healing assay using Src, Yes, Fyn null cells (SYF−/−) and SYF−/− cells with reintroduced c-Src (SYF-Src), treated with 0.01% DMSO vehicle control or increasing concentrations of SKI-606 and allowed to migrate for 48 h. B) Cells were seeded in serum-free medium in the top layer of an invasion chamber in the presence or absence of 0.01% DMSO, 250 nM or 1 µM SKI-606 and allowed to invade the chamber towards cell-specific conditioned medium for 48 h. Photomicrographs were taken under brightfield illumination (4x magnification). C) Invasion potential of SYF−/− and SYF-Src cells treated with 0.0025% DMSO or 250 nM SKI-606. Values represent the % of invasive cells compared to DMSO vehicle control SYF-Src treated cells and are shown as mean±S.E. of three independent experiments. *p<0.009 (one-sided t-test versus SYF-Src cells with 100% invasion potential).

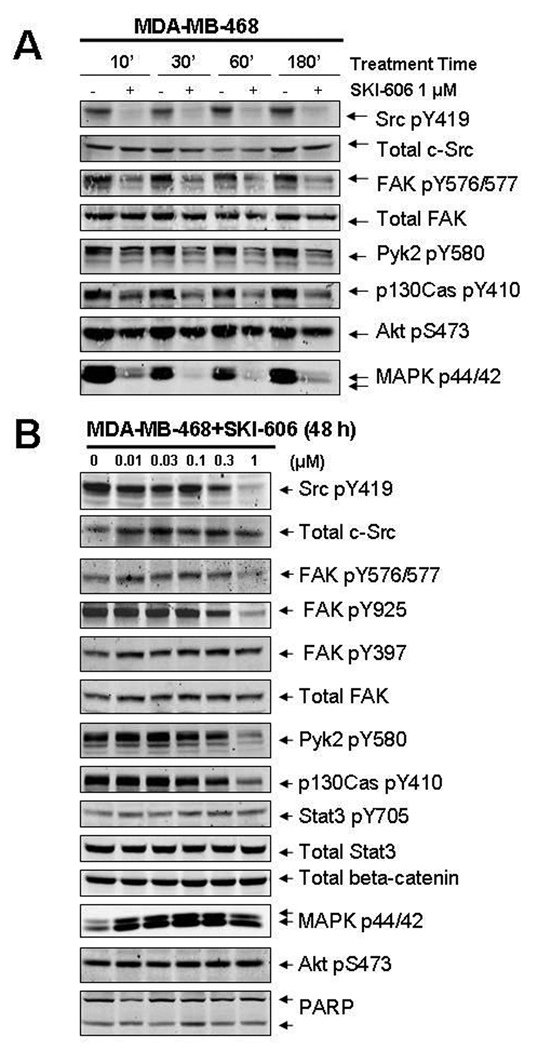

SKI-606 inhibits Src, FAK, and p130Cas phosphorylation

To determine the effects of SKI-606 on signaling pathways within our human cancer cell lines, we investigated several phosphorylated downstream effectors of Src in multiple human cell lines including MDA-MB-468, MDA-MB-231, MDAMB-435s, MDA-MB-453, and MCF-7. We observed a rapid (within 10 min; Fig. 4A) and prolonged concentration-dependent inhibition (at 48 h; Fig. 4B) in these cells of phosphorylated Tyr576, Tyr577, Tyr925 on FAK, Tyr580 on Pyk2, and Tyr410 on p130Cas. This inhibition was coincident with the decline of Src autophosphorylation at Tyr419, which reflects Src kinase activity in cells, with an IC50 of ~300 nM. No significant changes were observed in phosphorylated Tyr397 on FAK (an autophosphorylation site (25)), demonstrating that FAK intrinsic kinase activity is not affected by SKI-606, while the Src-dependent FAK phosphorylation sites (Tyr576/577, Tyr925) are inhibited by SKI-606. No changes in total protein levels were observed for any of the signaling proteins examined despite the obvious changes in phosphorylation, and similar observations were made for all breast cancer patient-derived cell lines tested (data not shown).

Figure 4.

SKI-606 causes rapid and prolonged inhibition of Src/FAK/Pyk2/p130Cas phosphorylation. Western blot analysis of MDA-MB-468 whole cell extracts. Cells were treated with SKI-606 or 0.01% DMSO at the indicated concentrations for times up to A) 3 h or B) 48 h prior to extraction. Immunoblots were probed as indicated with antibodies to phospho-Src (pY419), phospho-FAK (pYpY576/577 or pY925), phospho-Pyk2 (pY580), phospho-p130Cas (pY410), phospho-Stat3 (pY705), phospho-Akt (pS473), phospho-MAPK p44/42, beta-catenin, or PARP. Blots were re-probed with total anti-Src, anti-FAK, or anti-Stat3 antibodies, as indicated.

We also examined other signaling pathways previously shown to be regulated by Src in different cellular contexts (Fig. 4). No changes were observed in the phosphorylation of Tyr705 in Stat3 and Ser473 in Akt at SKI-606 concentrations that decrease Src Tyr419 autophosphorylation, indicating that SKI-606 selectively inhibits the Src/FAK/Pyk2/p130Cas pathway in these breast cancer cell lines. This lack of inhibition of phosphorylated Stat3 and Akt, which are important in tumor cell survival, is consistent with our finding that SKI-606 does not induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Lack of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage further supports the observation that apoptosis was not induced by SKI-606 treatment of these cells. In addition, even though p44/p42 phosphorylation on Thr202/Tyr204 was inhibited at very early times (180 min; Fig. 4A) of SKI-606 treatment, by 48 h the phosphorylation levels of p44/p42 were restored (Fig. 4B), consistent with the observed lack of inhibition of cell proliferation by SKI-606 under these conditions. Analysis of the same signaling pathways after treatment with SKI-606 for 6 days (with redosing every 2 days) revealed results similar to those found at 48 h (data not shown), indicating that these signaling pathways stabilize after 48 h despite the initial changes observed upon immediate treatment with SKI-606.

SKI-606 causes an increase in membrane-localized beta-catenin and stabilization of cell-to-cell adhesions

Given our observations that SKI-606 causes cell motility defects and changes in FAK phosphorylation, we examined the localization of Src effectors found in focal adhesions in SKI-606 treated and untreated cells. Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed the disappearance of FAK pY576/pY577 upon SKI-606 treatment, supporting our findings by Western blot analysis, while total FAK protein staining was unchanged in the presence of SKI-606 despite the lack of migrating leading fronts (lamellipodia and/or filipodia) (Fig. 5A). These findings agree with the suggested role of c-Src in the dynamic turnover of focal adhesions rather than in their assembly (26). Interestingly, pY705-Stat3 failed to localize to focal adhesions despite total levels of the activated protein remaining unchanged. These observations agree with the findings of Silver et al. (27) who suggest that Src family members are required for normal localization of Stat3. Significantly, cell aggregation upon treatment with SKI-606 was accompanied by an increase in membrane-localized beta-catenin (Fig. 5A–B) although total levels of beta-catenin remained unchanged (Fig. 4B). These findings suggest the possibility that SKI-606 increases cell-to-cell adhesion via beta-catenin-mediated stabilization of cell surface adhesion molecules.

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence analysis of FAK and beta-catenin in cells treated with SKI-606. A) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 0.01% DMSO or 1 µM SKI-606 for 48 h then fixed, probed with antibodies to phospho-FAK (pY576/pY577), FAK, phospho-Stat3 (pY705) or beta-catenin as indicated, and stained with DAPI. Images were captured under fluorescence at 40x magnification. B) MCF-7 cells were treated with 0.01% DMSO or 1 µM SKI-606 for 48 h then fixed, probed with antibodies to beta-catenin antibodies or E-cadherin antibodies and stained with DAPI. Images were captured under fluorescence at 40x magnification.

Discussion

Src kinases are transducers of signals activated by many different classes of cell-surface receptors, they interact with a large number of substrates, and they mediate a wide array of biological events; therefore, predicting the outcome of interfering with these key effectors is not straightforward. What is clear however, through an increasing number of studies using a new generation of more selective small-molecule Src inhibitors, is that targeting SFK activity results in potent anti-neoplastic effects in a wide variety of different tumor cell types (14, 16, 28, 29). While differences arise in the biological effects of these compounds in terms of cell proliferation, survival, adhesion, and morphology, likely caused by off-target effects, inhibition of cell migration and invasion are consistently recurring responses (13, 15, 28, 30, 31).

Our present findings using the Src inhibitor SKI-606 on human cancer cell lines obtained from breast cancer patients demonstrate reduced cell migration and invasion. In addition, we show that these effects are accompanied by an increase in cell-to-cell adhesion. These responses occur at concentrations corresponding to detectable inhibition of Src autophosphorylation on Tyr419, suggesting that c-Src plays a key role in these events. The important role of c-Src signaling in mediating the response to SKI-606 is further demonstrated by our experiments using SYF−/− and SYF-Src cells. SKI-606 had minimal effects on SYF−/− cells which, when left untreated, migrated slowly and were unable to cross a Matrigel invasion chamber over 48 h. However, the same cells with c-Src re-introduced were highly migratory and invasive, unless treated with SKI-606, which inhibited cell migration and invasion. The ability of c-Src to have such effects upon cell migration and invasion, and for these effects to be blocked by SKI-606 at concentrations correlating with inhibition of Src kinase activity, provides compelling evidence that SKI-606 mediates its biological responses through inhibition of c-Src kinase. In addition, our results point towards the enhanced specificity of SKI-606 in targeting the Src kinase, since SYF−/− cells appeared mostly unaffected by the addition of the small molecule inhibitor.

Our data demonstrate that decreased cell motility and invasion are not associated with significant changes in cell proliferation or apoptosis. Thus, in the cancer cell lines studied herein, the signaling pathways responsible for cell proliferation and survival do not rely heavily on Src kinase activity. In particular, we show that phosphorylated Stat3, Akt and MAPK levels are not decreased upon extended exposure to SKI-606, consistent with the lack of effect on cell proliferation and survival. Furthermore, these signaling pathways can recover from Src kinase inhibition over time, as observed for MAPK phosphorylation at 3 h versus 48 h post-treatment. In striking contrast, low levels of phosphorylated Src, FAK and p130Cas are observed at 10 min and remain low even 6 days post-treatment, consistent with inhibition of migration and invasion. However, under conditions of reduced serum levels in the culture media, prolonged treatment with SKI-606 has been found to inhibit growth of some breast cancer cells (32). It is possible that the response of tumor cells to SKI-606 depends on the particular signaling circuitry and the cell’s ability to overcome Src inhibition by upregulating other pathways involved in growth and survival. We also found that cancer cells grown on three-dimensional reconstituted basement membranes or in soft agar and treated with SKI-606 formed condensed aggregates with few extending projections, suggesting that our experiments conducted in two-dimensional monolayer cultures are indicative of potential three-dimensional in vivo responses.

FAK is phosphorylated by Src on a number of tyrosine residues and, similar to Src, is also associated with malignant progression of breast cancer (33, 34). Given that Src-mediated activation of FAK negatively regulates cell-to-cell adhesion (35), the decrease in FAK phosphorylation on Src-dependent sites could at least partially account for the cell aggregation phenotype we observed upon SKI-606 treatment. In addition, decreased phosphorylation of FAK on Tyr925 upon SKI-606 treatment is correlated with the observed reduction in motility. These results agree with earlier findings by Brunton et al. (36), indicating that the Src kinase-dependent phosphorylation of Tyr925 in FAK is important in controlling the extension and retraction of cell protrusions or adhesion turnover. p130Cas (Crk-associated substrate), another substrate of c-Src with decreased phosphorylation upon SKI-606 treatment, is also involved in cell spreading, focal adhesion formation, motility and invasion, and its high expression is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients (37). As a scaffold protein, p130Cas associates with Src, FAK, Pyk2 and other signaling molecules in multi-protein complexes. Following treatment with SKI-606, we observed a decrease in phosphorylated Pyk2 (proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2) at Tyr580, a Src-specific phosphorylation site. Pyk2, also known as RAFTK/CADTK/FAK2/CAKβ, was previously shown to have an important role in transducing chemotactic signals in breast cancer cell lines (38) and mediating cell-cell adhesion by controlling beta-catenin phosphorylation (39).

Earlier studies using colorectal cells suggest that SKI-606 causes cell aggregation (19). Interference with Src-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of beta-catenin in this case could be regulating a switch between the adhesive and transcriptional functions of beta-catenin, thus promoting cell-to-cell adhesion and stabilizing E-cadherin proteins on the cell surface (29). Upon treatment with SKI-606, our breast cancer patient-derived cell lines also display tighter aggregates, associated with higher levels of membrane-localized beta-catenin. However, the cell surface receptors involved in SKI-606-mediated cell adhesion differ across cell lines and may be of secondary importance to this effect since both E-cadherin positive and negative cells form tight aggregates and exhibit reduced migration and invasion. Finally, the observed lack of Stat3 pY705 localized to focal adhesions, despite total activated levels of Stat3 pY705 remaining unchanged, point to the potential involvement of Stat3 in the invasive phenotype of human cancer cells in addition to their survival. However, the role of Stat3 in focal adhesions remains to be determined.

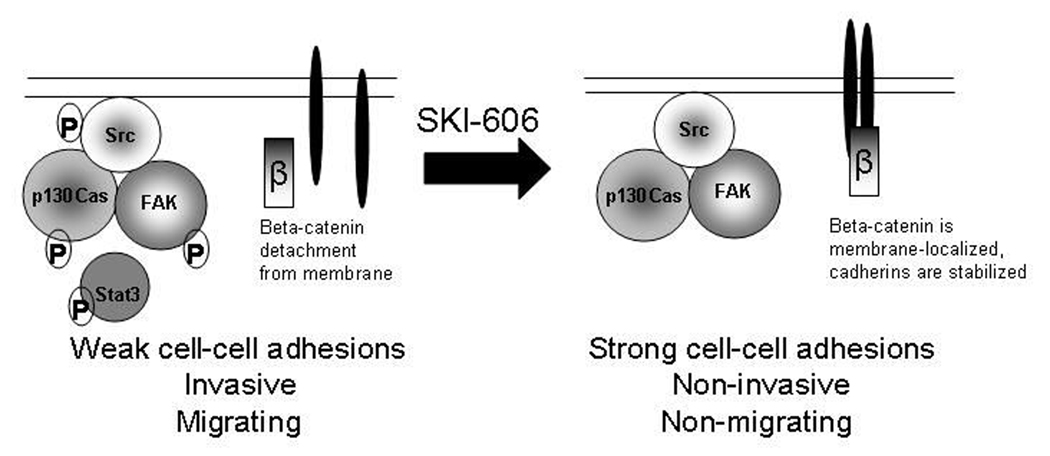

In sum, our studies showing decreased cell motility and invasion, as well as increased cell-cell adhesion, upon SKI-606 treatment suggest that SKI-606 has potential for the treatment of breast cancer and possibly other tumor sites. SKI-606 interferes with key cellular mechanisms and signaling pathways relied on extensively by cancer cells for invading and metastasizing, whereas cell proliferation and survival are not inhibited (summarized in Figure 6). Thus, Src kinase inhibitors such as SKI-606 may act independently of cytotoxic agents and instead enhance long-term survival of breast cancer patients by preventing tumor cell invasion and metastasis.

Figure 6.

Model for mechanism of action of SKI-606 in human breast cancer cells. SKI-606 inhibits Src kinase activity and thereby disrupts phosphorylation of the Src/FAK/p130Cas mutli-protein complex. SKI-606 also increases beta-catenin localization to the membrane and leads to loss of phosphorylated Stat3 from focal adhesion sites. The biological consequences of SKI-606 treatment are enhanced cell-to-cell adhesion, as well as reduced cell migration and invasion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratories for stimulating discussions. We also acknowledge the valuable contributions of George McNamara, Ph.D., for assistance with imaging. This work was performed with the assistance of the COH Analytical Cytometry Core and the COH Microscopy Core. Our research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada through a postdoctoral fellowship to A.V., as well as by NIH grants CA55652 and CA82533 to R.J.

Grant support: NSERC PDF fellowship (A. Vultur); NIH grants CA55652 and CA82533 (R. Jove).

Abbreviations

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- FGFR

fibroblast growth factor receptor

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- Pyk2

proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2

- p130Cas

Crk-associated substrate

- SFK

Src family kinase

- Stat3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- SYF−/−

Src/Fyn/Yes null cells

- SYF-Src

SYF−/− cells with c-Src reintroduced

- PARP

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PDGFR

platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- PTP1B

protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B

- VTLM

video time lapse microscopy

References

- 1.Frame MC. Src in cancer: deregulation and consequences for cell behaviour. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2002;1602:114–130. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishizawar R, Parsons SJ. c-Src and cooperating partners in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frame MC. Newest findings on the oldest oncogene; how activated src does it. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:989–998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen N, Bolen JB, Schwartz AM, Cohen P, DeSeau V, Israel MA. Analysis of pp60c-src protein kinase activity in human tumor cell lines and tissues. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13754–13759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ottenhoff-Kalff AE, Rijksen G, van Beurden EA, Hennipman A, Michels AA, Staal GE. Characterization of protein tyrosine kinases from human breast cancer: involvement of the c-src oncogene product. Cancer Res. 1992;52:4773–4778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verbeek BS, Vroom TM, Adriaansen-Slot SS, et al. c-Src protein expression is increased in human breast cancer An immunohistochemical and biochemical analysis. J Pathol. 1996;180:383–388. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199612)180:4<383::AID-PATH686>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reissig D, Clement J, Sanger J, Berndt A, Kosmehl H, Bohmer FD. Elevated activity and expression of Src-family kinases in human breast carcinoma tissue versus matched non-tumor tissue. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2001;127:226–230. doi: 10.1007/s004320000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz N, Minton S, Cox C, et al. Activation of stat3 in primary tumors from high-risk breast cancer patients is associated with elevated levels of activated SRC and survivin expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:20–28. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahimi N, Hung W, Tremblay E, Saulnier R, Elliott B. c-Src kinase activity is required for hepatocyte growth factor-induced motility and anchorage-independent growth of mammary carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33714–33721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Summy JM, Gallick GE. Src family kinases in tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:337–358. doi: 10.1023/a:1023772912750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjorge JD, Pang A, Fujita DJ. Identification of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B as the major tyrosine phosphatase activity capable of dephosphorylating and activating c-Src in several human breast cancer cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41439–41446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson FM, Saigal B, Talpaz M, Donato NJ. Dasatinib (BMS-354825) tyrosine kinase inhibitor suppresses invasion and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6924–6932. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song L, Morris M, Bagui T, Lee FY, Jove R, Haura EB. Dasatinib (BMS-354825) selectively induces apoptosis in lung cancer cells dependent on epidermal growth factor receptor signaling for survival. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5542–5548. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rucci N, Recchia I, Angelucci A, et al. Inhibition of protein kinase c-Src reduces the incidence of breast cancer metastases and increases survival in mice: implications for therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:161–172. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.102004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trevino JG, Summy JM, Lesslie DP, et al. Inhibition of SRC expression and activity inhibits tumor progression and metastasis of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells in an orthotopic nude mouse model. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:962–972. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg PA, Hortobagyi GN, Smith TL, Ziegler LD, Frye DK, Buzdar AU. Long-term follow-up of patients with complete remission following combination chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2197–2205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.8.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golas JM, Arndt K, Etienne C, et al. SKI-606, a 4-anilino-3-quinolinecarbonitrile dual inhibitor of Src and Abl kinases, is a potent antiproliferative agent against chronic myelogenous leukemia cells in culture and causes regression of K562 xenografts in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golas JM, Lucas J, Etienne C, et al. SKI-606, a Src/Abl inhibitor with in vivo activity in colon tumor xenograft models. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5358–5364. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raptis L, Vultur A. Neoplastic transformation assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;165:151–164. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-117-5:151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vultur A, Arulanandam R, Turkson J, Niu G, Jove R, Raptis L. Stat3 is required for full neoplastic transformation by the Simian Virus 40 large tumor antigen. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3832–3846. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Debnath J, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods. 2003;30:256–268. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belsches-Jablonski AP, Biscardi JS, Peavy DR, Tice DA, Romney DA, Parsons SJ. Src family kinases and HER2 interactions in human breast cancer cell growth and survival. Oncogene. 2001;20:1465–1475. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klinghoffer RA, Sachsenmaier C, Cooper JA, Soriano P. Src family kinases are required for integrin but not PDGFR signal transduction. Embo J. 1999;18:2459–2471. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaller MD, Hildebrand JD, Shannon JD, Fox JW, Vines RR, Parsons JT. Autophosphorylation of the focal adhesion kinase, pp125FAK, directs SH2- dependent binding of pp60src. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1680–1688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fincham VJ, Frame MC. The catalytic activity of Src is dispensable for translocation to focal adhesions but controls the turnover of these structures during cell motility. Embo J. 1998;17:81–92. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silver DL, Naora H, Liu J, Cheng W, Montell DJ. Activated signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3: localization in focal adhesions and function in ovarian cancer cell motility. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3550–3558. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam S, Kim D, Cheng JQ, et al. Action of the Src family kinase inhibitor, dasatinib (BMS-354825), on human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9185–9189. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coluccia AM, Benati D, Dekhil H, De Filippo A, Lan C, Gambacorti-Passerini C. SKI-606 decreases growth and motility of colorectal cancer cells by preventing pp60(c-Src)-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of beta-catenin and its nuclear signaling. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2279–2286. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan M, Li P, Klos KS, et al. ErbB2 promotes Src synthesis and stability: novel mechanisms of Src activation that confer breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1858–1867. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez L, Agullo-Ortuno MT, Garcia-Martinez JM, et al. Role of c-Src in human MCF7 breast cancer cell tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20851–20864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601570200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jallal H, Valentino ML, Chen G, Boschelli F, Ali S, Rabbani SA. A Src/Abl kinase inhibitor, SKI-606, blocks breast cancer invasion, growth, and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1580–1588. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cance WG, Harris JE, Iacocca MV, et al. Immunohistochemical analyses of focal adhesion kinase expression in benign and malignant human breast and colon tissues: correlation with preinvasive and invasive phenotypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2417–2423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watermann DO, Gabriel B, Jager M, et al. Specific induction of pp125 focal adhesion kinase in human breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:694–698. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avizienyte E, Frame MC. Src and FAK signalling controls adhesion fate and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunton VG, Avizienyte E, Fincham VJ, et al. Identification of Src-specific phosphorylation site on focal adhesion kinase: dissection of the role of Src SH2 and catalytic functions and their consequences for tumor cell behavior. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1335–1342. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Defilippi P, Di Stefano P, Cabodi S. p130Cas: a versatile scaffold in signaling networks. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zrihan-Licht S, Avraham S, Jiang S, Fu Y, Avraham HK. Coupling of RAFTK/Pyk2 kinase with c-Abl and their role in the migration of breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Buul JD, Anthony EC, Fernandez-Borja M, Burridge K, Hordijk PL. Proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) mediates vascular endothelial-cadherin-based cell-cell adhesion by regulating beta-catenin tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21129–21136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.