Abstract

Personal characteristics that interact with both HIV diagnosis and its medical management can influence symptom experience. Little is known about how symptoms in chronic illness populations vary by age, sex, or socioeconomic factors. As part of an ongoing prospective longitudinal study, this study describes symptoms experienced by 317 men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Participants were recruited at HIV clinics and community sites in the San Francisco Bay area. Measures included their most recent CD4 cell count and viral load from the medical record, demographic and treatment variables, and the 32-item Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale to estimate prevalence, severity, and distress of each symptom as well as global symptom burden. The median number of symptoms was nine, and symptoms experienced by over half the sample included lack of energy (65%), feeling drowsy (57%), difficulty sleeping (56%), and pain (55%). Global symptom burden was unrelated to age or CD4 cell count. Those with an AIDS diagnosis had significantly higher symptom burden scores, as did those currently receiving anti-retroviral (ART) therapy. African Americans reported fewer symptoms than Caucasians or Mixed/Other race and women reported more symptom burden after controlling for AIDS diagnosis and race. Since high symptom burden is more likely to precipitate self-care strategies that may potentially be ineffective, strategies for symptom management would be better guided by tailored interventions from health care providers.

Keywords: HIV, gender, sex, transgender, ethnicity, race, symptoms, sleep, fatigue, pain

The tragedy of HIV infection is that it most often strikes young adults between 25–39 years of age, the time of greatest potential for productive vocations or careers (1,2). With better therapies, adults with HIV/AIDS are living longer, and health care providers are shifting to a chronic illness model to better manage symptoms associated with HIV infection and treatment. Previous research on the symptom experience of adults living with HIV/AIDS has been devoted to characterizing the prevalence of various symptoms, with some attention to side effects of therapy (3) or extent of the disease process (4,5). Yet there has been little contrast by gender or social roles and socioeconomic factors that could influence symptom burden experienced within the same disease population.

Epidemiological data from surveys of the general population indicate that women experience more symptoms than men (6) and this sex difference is also evident for disease-specific populations (7–9). Even among children living with parents who are HIV-positive, it is adolescent daughters who experience more symptoms than sons (10). In HIV-infected adults, studies of symptoms have either focused on very ill patients with AIDS, lacked sufficient women in the sample for an adequate analysis for sex differences, or focused on one specific symptom. Compared to men, the women in a sample of Hispanics and African Americans in East Harlem were more likely to delay HIV treatment, have more symptoms, and have more emergency room visits (11).

Sex differences in symptom experience may be a result of self-report bias, with men less willing to disclose their symptom experience than women, or women feeling more distressed by their symptoms and conveying that distress in their self-report. Interactions between female sex hormones and symptoms may also explain sex differences. Anxiety, pain, and depressive symptoms have been shown to be mediated by estrogen or progesterone in laboratory settings with animal models and humans (12). For clinicians, patients and researchers, it is important to increase knowledge about symptoms experienced by men and women living with HIV infection so that better management strategies can be developed proactively (13). Measurable health outcomes such as adherence to medical treatment regimens, physical and cognitive functioning, and overall quality of life could be enhanced with new knowledge to develop and test tailored approaches to symptom management in this population.

The aim of this paper is to describe the extent to which personal characteristics may influence symptoms experienced by adults with HIV/AIDS. As part of a larger longitudinal study on symptoms, the purpose of this report is to describe the initial prevalence of various symptoms and symptom burden for men and women living with HIV. From a review of the current literature, we hypothesized that symptoms are likely to worsen with age and disease progression, and symptoms are likely to differ by type of medical therapy regimen. We further hypothesized that men and women, within the context of their family, work and social responsibilities, might differ in their symptom experience.

Methods

Participants

The Symptom and Genetic Study is an ongoing prospective, longitudinal study aimed at identifying biomarkers of symptom experience among HIV-infected adults. This analysis addresses symptom experience at the initial assessment of adults living with HIV in the San Francisco area. The study protocol was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation. Eligible subjects were English-speaking adults at least 18 years of age and had been diagnosed with HIV at least three months prior to enrollment. In order to specifically address stable HIV-related symptom experience, potential participants were excluded if they currently used illicit drugs (as determined by self-report or by positive urine drug testing), worked nights (i.e., at least four hours between 12AM-6AM), reported having a diagnosed sleep disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or dementia, or were pregnant within the prior three months.

Adults were recruited using flyers posted at approved local HIV clinics and approved community sites. Study visits were conducted at the UCSF General Clinical Research Center. In addition to completing the demographic and symptom questionnaires, the baseline assessment included a fasting blood sample for genetic and metabolic analysis, wearing a wrist actigraph to monitor sleep and activity patterns for 72 hours, and obtaining anthropometric measures of height, weight, and circumference of neck, waist, hips, and thighs. Participants also provided urine samples for toxicology screening using RediCup® (Redwood Toxicology Laboratory, Inc., Santa Rosa, CA, USA). This analysis reports on symptom experience data at the baseline assessment in relation to demographic characteristics of the sample of adults living with HIV in the San Francisco area.

Measures

Demographics and clinical information were obtained by self report, and CD4 and viral load levels were obtained from the most recent lab report in the patient’s medical record. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) was used to assess participants’ symptom burden (14). It is a reliable and valid self-report measure that has been used in a variety of clinical populations (15,16), including patients with HIV (3). The MSAS evaluates symptom prevalence, frequency, severity, and distress using four- or five-point Likert scales. Individual symptom scores were computed for each symptom as the average score on the severity, frequency, and distress scales. If the respondent did not report the symptom, the individual symptom score was 0. The 32 individual symptom scores were averaged to yield a total MSAS score. In addition, three previously validated subscale scores were computed: 1) PSYCH is the average of six psychological symptom scores, 2) PHYS is the average score of 12 prevalent physical symptoms, and 3) Global Distress Index (GDI) is a measure of overall symptom distress calculated as the average frequency score for four prevalent psychological symptoms and average distress scores for six prevalent physical symptoms. The scores for each individual symptom and for each subscale range from 0 to 4. Cronbach alpha coefficients for GDI, PHYS, and PSYCH in this sample were 0.78, 0.76, and 0.81, respectively.

Given that previous studies have reported a high prevalence of fatigue and sleep problems among adults with HIV, the symptom scores for “lack of energy,” “feeling drowsy” and “difficulty sleeping” were averaged to determine a SLEEP subscale score. The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the three-item scale was 0.74 in this sample. Three additional items were also included to assess specific types of sleep disturbance: problems falling asleep at bedtime, problems staying asleep during the night, and problems staying awake during the day. These three additional symptoms help to distinguish insomnia subtypes that would require different tailored approaches to intervention.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 14.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample, to describe prevalence, frequency, severity, and distress associated with individual symptoms, and to quantify overall symptom burden. Square root transformations were used to normalize the skewed distributions of symptom scores, and a logarithmic transformation was used to normalize viral load values. Demographic differences in symptom experience were assessed using unpaired t-tests or ANOVA with Scheffé post-hoc testing, and results were confirmed with non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis). Spearman correlations were used to determine associations between ordinal or non-normally distributed variables (individual symptoms scores, age, income, CD4, viral load, and time since diagnosis). Demographic variables were analyzed using levels described in Table 1. CD4 count and viral load were analyzed as continuous variables and as clinically meaningful categories (e.g., CD4 <200 and detectable VL). Effect sizes in standard deviation units were calculated to evaluate clinically meaningful differences without undue focus on statistical power or sample size.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample

| Male (n=216) |

Female (n=78) |

Transgender (n=23) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 45.1 ± 8.3 | 45.9 ± 8.2 | 43.3 ± 9.1 |

| Range | 22–77 | 26–66 | 27–60 |

| Race | |||

| White/Caucasian | 50% | 23% | 13% |

| Black/African American | 28% | 61% | 61% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 11% | 8% | 13% |

| More than one race | 8% | 4% | 9% |

| Other | 3% | 4% | 4% |

| Education | |||

| High school/GED or less | 37% | 60% | 65% |

| Some college/trade school | 38% | 26% | 22% |

| Completed college | 25% | 14% | 13% |

| Employment | |||

| Medical leave/disability | 72% | 81% | 83% |

| Employed/student | 18% | 10% | 13% |

| Not employed | 10% | 9% | 4% |

| Household income (monthly) | |||

| <$1000 | 66% | 77% | 74% |

| $1,000-$1999 | 22% | 20% | 26% |

| ≥$2,000 | 12% | 3% | 0% |

| In a relationship | 31% | 47% | 26% |

| Have children | 23% | 81% | 4% |

| Time since HIV diagnosis | |||

| Mean ± SD (yrs) | 12.4 ± 7.0 | 11.1 ± 6.5 | 11.5 ± 7.4 |

| Range (yrs) | 0.2 – 25.0 | 0.2 – 27.0 | 1.0 – 26.0 |

| AIDS diagnosis | 56% | 46% | 35% |

| On anti-retroviral (ART) therapy | 74% | 63% | 65% |

| CD4 (cells/mm3) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 462 ± 275 | 439 ± 246 | 380 ± 232 |

| Range | 4 – 1740 | 4 – 950 | 7 – 864 |

| % <200 | 16% | 17% | 26% |

| % <500 | 59% | 61% | 70% |

| Viral load (copies/mL) | |||

| % with detectable VL | 47% | 51% | 73% |

| Mean of detectable VL ± SD | 37,905 ± 84,824 | 68,954 ± 153,712 | 14,651 ± 23,163 |

| Range of detectable VL | 63 – 500,000 | 91 – 500,000 | 50 – 80,428 |

Hierarchical linear regression analysis was used to determine the unique contributions of demographic and clinical characteristics to symptom experience. All demographic variables from Table 1 were entered as Step 1 into the model, and retained for the final model if significance was P < 0.10. All clinical variables from Table 1 were entered into the model as Step 2, and retained for the final model if significance was P < 0.10. Interaction terms between the significant predictors in Step 1 and Step 2 were then created to test the overall three-step regression model. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sample Characteristics

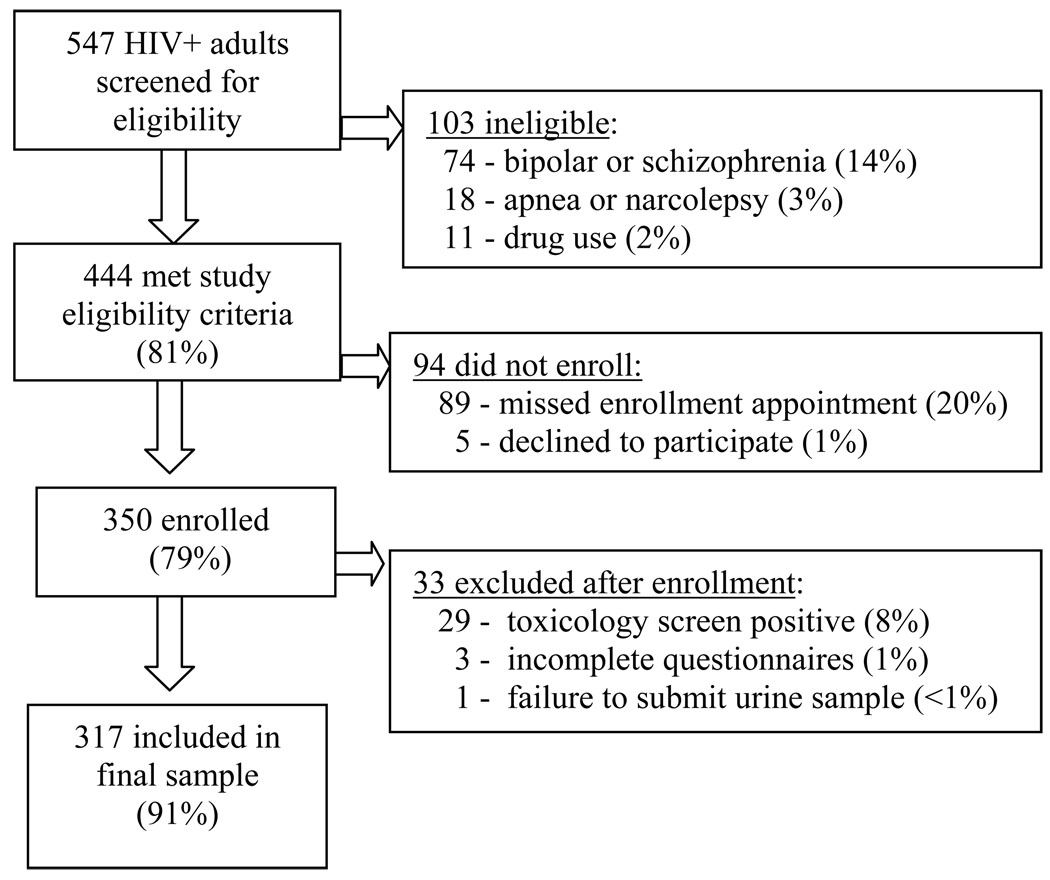

A convenience sample of 350 adults with HIV was enrolled in this study over a three-year period (April 2005 – December 2007). Three had incomplete symptom data, 29 were excluded from this analysis after screening positive for illicit drugs (cocaine, amphetamine, ecstasy, methamphetamine, or phencyclidine), and one was excluded after being unable to submit a urine sample for screening (Figure 1). Demographics and clinical characteristics for the 317 participants included in the final sample are presented in Table 1. The sample was ethnically diverse and predominantly male, reflecting the local population of adults with HIV. Over half (61%) of the 78 women in the sample were African American. Most participants had been living with HIV for many years, 71% were currently receiving ART therapy, they were currently taking an average of 6.5 ± 4.3 medications (median 6, range 0–25), 51% had been diagnosed with AIDS for an average of 8 years, and 28% of those with an AIDS diagnosis had a current CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mm3. Most (75%) were receiving medical disability assistance.

Figure 1.

Sample flowchart for recruitment, eligibility, and enrollment.

Symptom Prevalence

Of the 32 symptoms included in the MSAS, participants reported a median number of nine (range 0 – 32). The most prevalent symptoms were lack of energy, difficulty sleeping, and pain; these symptoms were reported by a majority of the sample. Psychological symptoms were also prevalent, with nearly half the sample reporting difficulty concentrating, irritability, or feelings of worry and sadness. Symptom frequency, severity, and distress ratings are reported in Table 2. Table 3 includes symptom scores by gender, race/ethnicity and HIV disease-specific characteristics.

Table 2.

Symptom Prevalence and Burden Among Adults with HIV Infection (n=317)

| Of Those Reporting Each Symptom | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | % Reporting Symptom |

Mean Symptom Score (SD) |

% Reporting High Frequencya |

% Reporting High Severityb |

% Reporting High Distressc |

| 1. Lack of energy | 65% | 1.5 (1.3) | 47% | 27% | 36% |

| 2. Feeling drowsy | 57% | 1.1 (1.1) | 31% | 18% | 16% |

| 3. Difficulty sleeping | 56% | 1.4 (1.4) | 55% | 33% | 36% |

| Problems staying asleep at night |

49% | 1.2 (1.4) | 58% | 40% | 41% |

| Problems falling asleep at bedtime |

43% | 1.0 (1.3) | 48% | 35% | 34% |

| Problems staying awake during day |

33% | 0.7 (1.1) | 32% | 22% | 22% |

| 4. Pain | 55% | 1.4 (1.4) | 60% | 34% | 43% |

| 5. Difficulty concentrating | 50% | 1.1 (1.2) | 35% | 15% | 29% |

| 6. Feeling irritable | 50% | 1.1 (1.2) | 32% | 23% | 27% |

| 7. Worrying | 48% | 1.1 (1.3) | 44% | 31% | 40% |

| 8. Feeling sad | 45% | 0.9 (1.2) | 36% | 21% | 34% |

| 9. Numbness/tingling in hands/feet |

44% | 1.1 (1.4) | 67% | 37% | 38% |

| Abnormal sensation or urge to move legs |

25% | 0.6 (1.1) | 54% | 43% | 38% |

| 10. Feeling nervous | 41% | 0.8 (1.1) | 34% | 19% | 24% |

| 11. Dry mouth | 36% | 0.8 (1.2) | 48% | 30% | 27% |

| 12. Cough | 34% | 0.6 (1.0) | 32% | 13% | 17% |

| 13. Lack of appetite | 31% | 0.7 (1.2) | 52% | 28% | 31% |

| 14. Feeling bloated | 27% | 0.6 (1.2) | 42% | 36% | 31% |

| 15. Sweats | 27% | 0.6 (1.1) | 48% | 30% | 41% |

| 16. Diarrhea | 26% | 0.6 (1.1) | 48% | 31% | 33% |

| 17. Problems with sexual interest/activity |

25% | 0.7 (1.3) | 69% | 47% | 47% |

| 18. Itching | 23% | 0.6 (1.2) | 59% | 43% | 47% |

| 19. Shortness of breath | 22% | 0.5 (1.0) | 37% | 24% | 29% |

| 20. Nausea | 22% | 0.5 (1.0) | 37% | 27% | 33% |

| 21. Constipation | 17% | 0.4 (0.9) | - | 28% | 27% |

| 22. Changes in skin | 16% | 0.4 (0.9) | - | 19% | 42% |

| 23. Problems with urination | 15% | 0.4 (1.0) | 63% | 31% | 38% |

| 24. Dizziness | 15% | 0.3 (0.8) | 28% | 21% | 22% |

| 25. “I don’t look like myself” | 14% | 0.4 (1.0) | - | 32% | 48% |

| 26. Vomiting | 9% | 0.2 (0.6) | 30% | 14% | 31% |

| 27. Mouth sores | 9% | 0.2 (0.6) | - | 10% | 38% |

| 28. Weight loss | 9% | 0.2 (0.7) | - | 22% | 34% |

| 29. Difficulty swallowing | 8% | 0.2 (0.7) | 39% | 27% | 32% |

| 30. Hair loss | 8% | 0.2 (0.7) | - | 41% | 52% |

| 31. Change in food tastes | 8% | 0.2 (0.6) | - | 19% | 20% |

| 32. Swelling of arms or legs | 7% | 0.2 (0.7) | - | 28% | 33% |

Reporting frequency as frequently or almost constantly.

Reporting severity as severe or very severe.

Reporting distress as quite a bit or very much.

Table 3.

Global Symptom Measures by Demographic Characteristics

| Mean Number of Symptoms Reported |

MSAS Total | GDI | PHYS | PSYCH | SLEEP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 9.15 ± 5.94 | 0.65 ± 0.49 | 1.00 ± 0.73 | 0.65 ± 0.53 | 1.06 ± 0.88 | 1.33 ± 1.01 |

| Self-Identified Gender | ||||||

| Female (n=78) | 9.64 ± 6.07 | 0.72 ± 0.52 | 1.10 ± 0.80 | 0.72 ± 0.57 | 1.15 ± 0.91 | 1.35 ± 1.06 |

| Male (n=216) | 9.11 ± 5.87 | 0.63 ± 0.48 | 0.99 ± 0.71 | 0.64 ± 0.51 | 1.06 ± 0.89 | 1.33 ± 0.99 |

| Transgender (n=23) | 7.96 ± 6.18 | 0.55 ± 0.44 | 0.76 ± 0.61 | 0.58 ± 0.54 | 0.85 ± 0.71 | 1.25 ± 1.12 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| African American (n=123) | 7.67 ± 6.22a | 0.54 ± 0.49b | 0.76 ± 0.70c | 0.51 ± 0.50d | 0.83 ± 0.84e | 1.04 ± 0.98f |

| Caucasian (n=129) | 9.62 ± 5.23a | 0.65 ± 0.40b | 1.07 ± 0.67c | 0.69 ± 0.44d | 1.11 ± 0.83e | 1.49 ± 0.99f |

| Mixed/Asian/Other (n=33) | 10.73 ± 5.81a | 0.77 ± 0.53b | 1.20 ± 0.79c | 0.79 ± 0.58d | 1.30 ± 0.93 | 1.60 ± 0.91f |

| Hispanic/Latino (n=32) | 11.34 ± 6.49a | 0.91 ± 0.64b | 1.38 ± 0.76c | 0.90 ± 0.74d | 1.57 ± 0.93e | 1.54 ± 1.12 |

| AIDS Diagnosis | ||||||

| No (n=152) | 8.18 ± 5.49 h | 0.58 ± 0.45 g | 0.94 ± 0.70 | 0.58 ± 0.49g | 1.01 ± 0.84 | 1.21 ± 1.00 g |

| Yes (n=165) | 10.05 ± 6.20 | 0.72 ± 0.51 | 1.05 ± 0.76 | 0.72 ± 0.55 | 1.12 ± 0.91 | 1.44 ± 1.02 |

| CD4 (cells/mm3) | ||||||

| ≥200 (n=250) | 8.92 ± 5.88 | 0.62 ± 0.47 | 0.96 ± 0.71 | 0.62 ± 0.52g | 1.04 ± 0.84 | 1.26 ± 0.99 |

| <200 (n=52) | 9.96 ± 6.10 | 0.75 ± 0.56 | 1.07 ± 0.77 | 0.80 ± 0.57 | 1.00 ± 0.96 | 1.48 ± 1.10 |

| Anti-Retroviral Therapy | ||||||

| Not on treatment (n=94) | 8.13 ± 5.77 g | 0.59 ± 0.49 | 0.96 ± 0.72 | 0.60 ± 0.54 | 1.00 ± 0.84 | 1.16 ± 1.04 g |

| On treatment (n=223) | 9.59 ± 5.97 | 0.67 ± 0.49 | 1.01 ± 0.74 | 0.67 ± 0.52 | 1.09 ± 0.90 | 1.40 ± 1.00 |

Note: comparisons are based on square-root transformed scores.

Black/African-American adults reported fewer symptoms than White/Caucasian adults (Scheffé P=0.009), Hispanic/Latino adults (P=0.009), and Mixed/Other adults (P=0.018).

Black/African-American adults had lower MSAS total scores than Hispanic/Latino adults (P=0.001), Mixed/Other adults (P=0.034), and White/Caucasian adults (P=0.041).

Black/African-American adults had lower GDI scores than White/Caucasian adults (P<0.001), Hispanic/Latino adults (P<0.001), and Mixed/Other adults (P=0.008).

Black/African-American adults had lower PHYS scores than White/Caucasian adults (P=0.003), Hispanic/Latino adults (P=0.008), and Mixed/Other adults (P=0.013).

Black/African-American adults had lower PSYCH scores than Hispanic/Latino adults (P=0.001) and White/Caucasian adults (P=0.028).

Black/African-American adults had lower SLEEP scores than White/Caucasian adults (P=0.005) and Mixed/Other adults (P=0.033).

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

Sleep-Related Symptoms

As presented in Table 3, the SLEEP subscale score was the highest of the subscale scores, reflecting significant burden from sleep and fatigue symptoms in this population. This symptom burden was examined more specifically with the three additional sleep-related items. Difficulty falling asleep (initiation insomnia) was experienced by 43% of the sample. Difficulty staying asleep during the night (maintenance insomnia) was the most prevalent type of sleep problem (49%), and 33% reported difficulty staying awake during the day. Only 17% reported having all three types of sleep disturbance. The MSAS item “difficulty sleeping” was correlated with problems falling asleep (r = 0.72) and staying asleep (r = 0.68) rather than with problems staying awake (r = 0.24). The MSAS item “lack of energy” was correlated with both “feeling drowsy” (r = 0.55) and “difficulty sleeping” (r = 0.53).

Demographic and Clinical Differences in Symptom Burden

In bivariate analyses, being male, female, or transgender was not associated with number of symptoms, MSAS burden score, or GDI, PSYCH, PHYS or SLEEP subscale scores, although the transgender participants reported slightly fewer symptoms and slightly less symptom burden on average (Table 3). Given the small number of transgender participants, the power to detect group differences was limited and effect sizes were calculated. The effect size difference between women and transgender adults was 0.30 standard deviation (SD) units for number of symptoms, 0.34 SD units for MSAS total score, 0.36 SD units for GDI, and 0.32 SD units for PSYCH. The effect size difference between men and transgender adults was 0.30 SD units for GDI, and all other effect sizes for gender differences were under 0.30 SD units.

Race/ethnicity was associated with global measures of symptom burden (Table 3). Due to the small numbers in specific racial groups, those identifying as being Asian or of more than one race, and those who selected “other” as a category option on the questionnaire, were grouped as Mixed/Other for the purpose of analysis. There were no differences between White/Caucasian, Hispanic/Latino, or Mixed/Other adults on any of the symptom burden measures. Black/African-American adults reported significantly fewer symptoms, had lower MSAS total scores, and had lower scores on GDI and PHYS compared to each of the other three racial groups. In addition, Black/African-American adults had lower PSYCH symptom subscale scores than Hispanic/Latino adults and White/Caucasian adults and had lower SLEEP subscale scores than White/Caucasian and Mixed/Other adults.

Symptom scores were unrelated to the demographic factors of age, employment, income, having a partner, or having children. However, those with at least some college education had worse SLEEP subscale scores (1.62 ± 0.88) than those with less education (1.25 ± 1.04; Mann Whitney U, P=0.005).

Several clinical characteristics were associated with measures of symptom burden. Those diagnosed with AIDS reported more symptoms, had higher MSAS total scores, and had higher scores on PHYS and SLEEP compared to those without an AIDS diagnosis (Table 3). CD4 cell count was not linearly correlated with any of the symptom indices; when CD4 cell count was dichotomized, those below 200 cells/mm3 had significantly higher scores on PHYS compared to those who were 200 cells/mm3 or higher. Global symptom measures were unrelated to viral load or time since HIV diagnosis. Those currently on ART reported a significantly higher number of symptoms and had higher SLEEP scores than those not on ART, but other symptom indices were unrelated to ART. The type of anti-retroviral regimen (NRTI based, PI based, or other combination therapy) had no unique effect on indices of symptom burden.

The unique contributions of demographic and clinical characteristics to symptom experience were then tested with a hierarchical regression analysis. Due to the positive skew of the symptom variable distributions, a square root transformation of symptom count was used as the dependent variable. All seven demographic factors (Table 1) were included in Step 1 of the model. Only race (dummy coded as Black=0 vs. not Black) and gender (dummy coded as female=0 vs. not female) were significant demographic factors (P <0.10) retained for the final model. All five of the clinical factors (see Table 1) were included in Step 2 of the model, and only viral load (log transformed) and taking ART therapy (yes/no) were significant and retained for the final model. For Step 3, interaction terms were created for these four variables and only gender-by-ART was a significant (P < 0.10) interaction term. As seen in Table 4, the two demographic factors accounted for 7% of the variance in symptom count, with African Americans having lower symptom burden and females having higher symptom burden. The two clinical factors (ART and detectable viral load) accounted for 3.4% of the variance in symptoms after controlling for race and gender. There was an interaction between gender and ART, however, with women on ART and men or transgendered adults on ART having a different symptom experience. Being male or transgendered and taking ART accounted for an additional 2.6% of the variance in symptoms, and was associated with more symptom burden, while women taking ART had less symptom burden. Overall, the three-step regression model with five independent variables accounted for 13% of the variance in symptom burden as measured by total symptom count on the MSAS (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis for the Prediction of Symptom Burden (n=309)

| Step | β | F for Δ R2 | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 – Demographic | F(2,306) = 11.56 a | 0.070 | |

| Black (vs not Black) | −0.274 a | ||

| Male/Transgender (vs Female) | −0.359 a | ||

| Step 2 – Clinical | F(2,304) = 5.78 b | 0.034 | |

| ART therapy (vs none) | −0.041 | ||

| Viral load (log) | 0.158 c | ||

| Step 3 – Interactions | F(1,303) = 8.83 b | 0.026 | |

| Male/Transgender X ART therapy | 0.391 b | ||

| Full Model | F(5,303) = 9.03 a | 0.130 | |

Note: Beta values are for the full model.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

Discussion

This sample of adults with HIV infection reported a median and mean of nine symptoms on the MSAS. There was no association between number of symptoms and number of medications prescribed. Those on ART therapy had more symptoms (9.6) compared to those not on ART (8.1). This is a much lower number than previously reported for men and women with advanced HIV disease before (27.7) and after (29.0) starting ART therapy.(17) This is also lower than what has been reported in a sample of British men with HIV disease who completed an online MSAS survey and averaged 14 symptoms for those on ART and 10.3 for those not on ART (3). While SLEEP was the only category of symptoms that was significantly worse for those on ART in our sample, the online sample of ART users reported more physical symptoms and higher GDI but similar psychological distress compared to those not on ART (3).

Lack of energy was the most prevalent (65%) symptom reported by this sample and supports findings from other samples of adults living with HIV/AIDS (3,4). Breitbart and colleagues (4) were the first to report that fatigue was more prevalent in women with AIDS (62%) compared to their male counterparts (49%). They reported an overall prevalence of 85% in their ambulatory patients diagnosed with AIDS, but found no evidence of an association with disease characteristics like CD4 cell count, time since diagnosis, or use of antiretroviral medications (4). Harding and colleagues (3) reported a higher endorsement for lack of energy in the online British sample of men taking ART (78.5%) compared to men not on ART (64%).

Fatigue is likely to result from many factors, including poor sleep (18–20) In a systematic review of the literature on insomnia in HIV infection, Reid and Dwyer (21) identified 29 studies in which insomnia was a primary outcome of the research, and only 11 of those studies included women. No differences in insomnia were found in the four studies that addressed age, sex and race (21). Our composite measure of SLEEP symptoms was highly correlated with the MSAS fatigue-related symptom “lack of energy” and a majority of our sample (55–56%) also experienced feeling drowsy and had difficulty sleeping. While 39% of the HIV clinic patients in Rubinstein and Selwyn’s (22) study took medications for sleep, only half found the medication helpful. This is troubling because of the association they also noted between sleep disturbance and mental health outcomes that include depression (22). In our sample, feeling sad was endorsed by 45% of the sample, a lower rate than reported in the online survey of men (76%) (3) but similar to the 40% reported by Rubinstein and Selwyn (22) in their sample of men and women with HIV and 49% reported by Leserman and colleagues in their sample of men and women using the Beck Depression Inventory (23).

A survey of sleep problems in the United States (24) concluded that women in the general population have a higher prevalence (61%) of sleep disturbance than men (53%). Cohen and colleagues (25) reported that 60% of their 50 HIV patients reported restless sleep, 26% complained of very poor sleep, and the prevalence was higher for males (70%) than females (45%). Feeling drowsy was more prevalent in our sample than problems staying awake during the day. Feeling drowsy may be a side effect of medications or lack of sleep, while difficulty staying awake during the day is often associated with severe sleep disorders like obstructive sleep apnea. Both of these symptoms may affect cognitive functioning and would be associated with the MSAS item “difficulty concentrating” that was experienced by 50% of our sample.

Pain was endorsed by 55% of our sample. Recent reviews on this topic place the prevalence of pain in the HIV/AIDS population somewhere between 30–90%, depending on progression of the disease and how it is defined and measured (26). A prevalence of 43% was reported in the online survey of British men (3), with a significant difference between those on HAART (51%) compared to those not on HAART (32%). In an earlier study with AIDS patients, persistent pain was present in 60% of the sample and was associated with being female as well as advanced disease and absence of antiretroviral medications (4).

Since the MSAS asks about pain in general, it would be important to explore the pain experience further in this population. In large epidemiology studies, chronic pain was more prevalent for females, older adults, and those who were divorced, separated or widowed (27). In an international study of unhealthy behaviors to manage HIV-related symptoms, researchers reported a 37% prevalence of peripheral neuropathy (28). Their Sign and Symptom Checklist of 64 items was translated into relevant languages and neuropathy was the fourth most frequent symptom, with 70% of the men and 29% of the women endorsing that item. Most interesting in this large international sample was the finding that those who had higher scores on this item also had a higher use of amphetamines, injection drug use, alcohol, and cigarette smoking (28). In our current sample, “numbness/tingling in hands/feet” was endorsed equally by 44% of men and 44% of women. Items about specific types and locations of pain could be useful additions to the MSAS in future studies with the HIV/AIDS population.

Similar to other studies, very little of the symptom experience in our sample was related to their disease characteristics or duration of infection. In a comprehensive cross-sectional study of men and women with AIDS, Breitbart and colleagues (4) found no difference in CD4 cell count or years since diagnosis between those who experienced fatigue and those who did not. In a sample of 35 women with HIV/AIDS followed for four months, Sarna and colleagues (29) also found no relationship between time since diagnosis and quality of life, which included fatigue and physical functioning.

From simple bivariate analyses, neither age nor gender were significantly associated with symptom burden. Zingmond and colleagues (30) did not report on gender differences, but found that younger adults were more likely to report some symptoms, such as headaches or diarrhea, while older adults were more likely to report weight loss and hair loss. They also found that White adults were more likely to report symptoms than non-Whites, and noted that age effects may be confounded with other factors such as race (30). We also found that other racial groups had higher symptom burden compared to the African Americans in our sample, a finding also supported in a recent study by Silverberg and colleagues (31). There may be genetic factors, or social support and spiritual factors, involved in the symptom experience that differ for certain ethnic and racial groups as well as for men and women living with HIV infection. African Americans may experience lower symptom burden as a result of self-care strategies that include prayer and spirituality. We did not include a measure of this concept, but Blinderman and colleagues (15) reported a median of nine symptoms using the MSAS in their sample of patients with advanced congestive heart failure and that sample also scored high on spirituality measures. Coleman and colleagues reported on the importance of spirituality to physical health and social well-being in the African American HIV/AIDS community (32) and also noted that more women used prayer to manage fatigue while more men used prayer to manage their depression (33).

In our overall regression analysis, the variance in symptom number was best accounted for by race, gender, viral load and use of ART. Being African American had a significant protective effect, as reported in other studies (30,31), and being female was associated with higher symptom burden, as noted by Silverberg and colleagues (31). Compared to the men, the majority of women (61%) and transgender (61%) in the sample were African American. Compared to men and transgender adults, women remain more symptomatic after consideration of ART, viral load, and race. Controlling for race and gender, those with a detectable viral load and those on ART had higher symptom burden. After controlling for race, gender, and clinical disease factors, gender and ART therapy interacted in such as way that women reported fewer symptoms and men and transgendered adults reported more symptoms. Results from our study would indicate that those on ART, regardless of current CD4 cell count or prior AIDS diagnosis, should be targeted for interventions to help manage their symptom experience and assure adequate adherence to their medication protocols.

The number of prescribed medications could have either a positive effect by treating the symptom, or a negative effect by causing a symptomatic side effect. There was no effect from number of medications on symptoms in this sample, and number of medications did not differ by gender. Those with an AIDS diagnosis reported taking more medications, and African Americans reported taking fewer medications than the other racial groups. Complementary and alternative therapies, in addition to specific types of prescribed medications, need to be considered in future studies. While African Americans may appear to be somewhat advantaged by fewer symptoms, this racial difference may be due to either fewer prescribed medications or more community and social support in the form of spiritual practices.

A number of limitations should be considered when interpreting the results from this study. First, because of the many exclusion criteria, the sample may not be representative of all HIV-infected adults. In order to describe their HIV-related symptom experience, those with severe mental health problems and those testing positive for illicit drugs at the time of data collection were excluded. Those who were pregnant, working night shift or diagnosed with a sleep disorder were excluded from participation to avoid erroneous conclusions about symptoms of fatigue or sleep problems. Second, this was a convenience sample of subjects recruited from a wide range of clinic and community sources who may have been more interested in participating in research than other adults living with HIV infection. Representation would be improved if the sample had been randomly selected from all patients diagnosed with HIV in the local community. Third, the overall 3-step regression model only accounted for 13% of the variance, leaving many other unexplained reasons for high symptom burden. Co-morbid health conditions and other factors such as adherence to therapy and prescriptive and non-prescriptive medication use should be explored in future research. Finally, participants self-identified as male, female, or transgendered and their sexual preference was not ascertained in this study. Given that lesbian and gay adults may have different psychological morbidity and symptom experiences than heterosexual adults, this should be explored in future studies with larger samples.

The findings in this study support the Theory of Symptom Management (34), in which characteristics of the individual (gender, age, race) interact with a health problem (HIV). This theory would also posit that, if their symptom experience is perceived as burdensome, it is more likely to initiate a management strategy that may be either self-care oriented or health care provider-initiated. When formulating and testing any type of intervention, the disproportionate impact of race and gender on HIV-infected adults needs to be considered (11–13). This is the first study to include findings about transgender HIV-infected adults as a separate self-identified gender category, and literature to date in this population has primarily focused on HIV prevention issues.

Adults who self-identify as male, female, or transgender require a tailored approach that is sensitive to minority issues of race and gender identity. Tailored management of their symptom experience is more likely to reduce symptom burden and improve their quality of life (35,36). Rather than relying on self-care strategies that may or may not be effective, empirically-driven interventions need to be tailored to those most affected (35). Since a high proportion of HIV-infected adults have a history of substance use, and there is a high prevalence of fatigue, sleep disturbance, and pain in this population, there may be a tendency toward poor adherence to prescribed therapy, or a tendency to resort to self-medication and illicit substances to manage current symptoms (36). Health care providers need to recognize the prevalence of these symptoms in the HIV-infected population and work with their patients using mutually-agreed upon strategies to manage their symptom burden.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions to the study from Ryan Kelly, Yeonsu Song, Kristen Nelson, and Matthew Shullick.

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH 5R01 MH074358). Data collection was supported by the General Clinical Research Center in the UCSF CTSA (1 UL RR024131). Dr. Aouizerat is also supported by an NIH Roadmap K12 (KL2 RR024130); Dr. Davis is supported by an NIH Research Infrastructure in Minority Institutions (RIMI) award (5P20 MD0005444).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed August 3, 2008];HIV/AIDS surveillance report. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/basic.htm#aidsage.

- 2.Harding R, Molloy T. Positive futures? The impact of HIV infection on achieving health, wealth and future planning. AIDS Care. 2008;20:565–570. doi: 10.1080/09540120701867222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harding R, Molloy T, Easterbrook P, Frame K, Higginson IJ. Is antiretroviral therapy associated with symptom prevalence and burden? International J STD & AIDS. 2006;17:400–405. doi: 10.1258/095646206777323409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breitbart W, McDonald MV, Rosenfeld B, Monkman ND, Passik SD. Fatigue in ambulatory AIDS patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;15:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(97)00260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogl D, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, et al. Symptom prevalence, characteristics, and distress in AIDS outpatients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallagher AM, Thomas JM, Hamilton WT, White PD. Incidence of fatigue symptoms and diagnoses presenting in UK primary care from 1990 to 2001. J Royal Soc Med. 2004;97:571–575. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.97.12.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladwig K-H, Muhlberger N, Walter H, et al. Gender differences in emotional disability and negative health perception in cardiac patients 6 months after stent implantation. J Psychosomatic Res. 2000;48:501–508. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naqvi TZ, Rafique AM, Andreas V, et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms post-acute coronary syndrome. Gender Med. 2007;4:339–351. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simren M, Svedlund J, Posserud I, Bjornsson ES, Abrahamsson H. Predictors of subjective fatigue in chronic gastrointestinal disease. Alimentary Pharm Ther. 2008;28:638–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bursch B, Lester P, Jiang L, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Weiss R. Psychosocial predictors of somatic symptoms in adolescents of parents with HIV: a six-year longitudinal study. AIDS Care. 2008;20:667–676. doi: 10.1080/09540120701687042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang S-Y, Goldstein MF, Deren S. Gender differences in health status and care among HIV-infected minority drug users. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1146–1151. doi: 10.1080/09540120701842746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rollman GB. Sex makes a difference: Experimental and clinical pain responses. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:204–207. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Donaghy KB, Portenoy RK. Pain and aberrant drug-related behaviors in medically ill patients with and without histories of substance abuse. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:173–181. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000161525.48245.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A(9):1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings A, Portenoy RK, Tennstedt SL. Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawicki GS, Sellers DE, Robinson WM. Self-reported physical and psychological symptom burden in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brechtl JR, Breitbart W, Galietta M, Krivo S, Rosenfeld B. The use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with advanced HIV infection: impact on medical, palliative care, and quality of life outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee KA, Portillo CJ, Miramontes H. The fatigue experience for women with human immunodeficiency virus. JOGNN. 1999;28:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1999.tb01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KA, Portillo C, Miramontes H. The influence of sleep and activity patterns on fatigue in women with HIV/AIDS. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2001;12 Supplement, 2001:19–27. doi: 10.1177/105532901773742257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Clinical predictors of functioning in persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Med Care. 1996;34:610–623. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reid S, Dwyer J. Insomnia in HIV infections: a systematic review of prevalence, correlates, and management. Psychosomatic Med. 2005;67:260–269. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000151771.46127.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubinstein ML, Selwyn PA. High prevalence of insomnia in an outpatient population with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1998;19:260–265. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199811010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leserman J, Barroso J, Pence BW, Salahuddin N, Harmon JL. Trauma, stressful life events and depression predict HIV-related fatigue. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1258–1265. doi: 10.1080/09540120801919410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Washington DC: National Sleep Foundation Omnibus Sleep in America Poll. 2000 Available at: www.sleepfoundation.org.

- 25.Cohen FL, Ferrans CE, Vizgirda V, Kunkle V, Cloninger L. Sleep in men and women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Holistic Nurse Practitioner. 1996;10:33–43. doi: 10.1097/00004650-199607000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sjogren P, Ekholm O, Peuckmann V, Gronbaek M. Epidemiology of chronic pain in Denmark: an update. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholas PK, Voss JG, Corless IB, et al. Unhealthy behaviours for self-management of HIV-related peripheral neuropathy. AIDS Care. 2007;19:1266–1273. doi: 10.1080/09540120701408928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarna L, van Servellen G, Padilla G, Brecht ML. Quality of life in women with symptomatic HIV/AIDS. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30:597–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverberg MJ, Jacobson LP, French AL, Witt MD, Gange SJ. Age and racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of reported symptoms in human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons on antiretroviral therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(2):197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zingmond DS, Kilbourne AM, Justice AC, et al. Differences in symptom expression in older HIV-positive patients: The Veterans Aging Cohort 3 Site Study and HIV Cost and Service Utilization Study experience. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33 Suppl 2:S84–S92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coleman CL. Spirituality and sexual orientation: relationship to mental well-being and functional health status. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43:457–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman CL, Holzemer WL, Eller LS, et al. Gender differences in use of prayer as a self-care strategy for managing symptoms in African Americans living with HIV/AIDS. J Assoc Nurses in AIDS Care. 2006;17:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Humphreys J, Lee KA, Carrieri-Kohlman V, et al. A middle range theory of symptom management. In: Smith MJ, Liehr PR, editors. Middle range theory for nursing. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2008. pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hudson A, Portillo C, Lee KA. Sleep disturbances in women with HIV or AIDS: efficacy of a tailored sleep promotion intervention. Nurs Res. 2008;57:360–366. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000313501.84604.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wisniewski AB, Apel S, Selnes OA, et al. Depressive symptoms, quality of life, and neuropsychological performance in HIV/AIDS: the impact of gender and injection drug use. J NeuroVirology. 2005;11:138–143. doi: 10.1080/13550280590922748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]