Abstract

αβδ-containing GABAA receptors are 1) localized to extra- and peri-synaptic membranes, 2) exhibit a high sensitivity to GABA, 3) show little desensitization, and 4) are believed to be one of the primary mediators of tonic inhibition in the central nervous system. This type of signaling appears to play a key role in controlling cell excitability. This review article briefly summarizes recent knowledge on tonic GABA-mediated inhibition. We will also consider the mechanism of action of many clinically important drugs such as anxiolytics, anticonvulsants, and sedative/hypnotics and their effects on δ-containing GABA receptor activation. We will conclude that αβδ-containing GABAA receptors exhibit a relatively low efficacy that can be potentiated by endogenous modulators and anxiolytic agents. This scenario enables these particular GABA receptor combinations, upon neurosteroid exposure for example, to impart a profound effect on excitability in the central nervous system.

Keywords: αβδ GABAA Receptors, Tonic inhibition, Tracazolate, Neurosteroids

Introduction to GABAA receptors

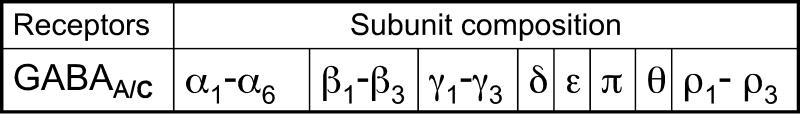

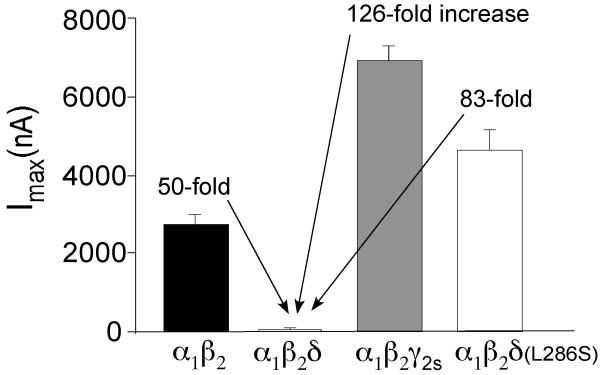

GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS). The inhibitory action of GABA is mediated by GABA receptors (GABARs), excluding early stages of development when GABA is excitatory (Valeyev et al., 1993; Owens et al., 1999; Demarque et al., 2002), and results in a reduction in neuronal excitability. Three types of GABA receptors have been characterized: GABAA, GABAB and GABAC. GABAA and GABAC receptors are ligand-gated chloride channels (Barnard et al., 1998; Sieghart and Sperk, 2002). GABAB receptors belong to the G-protein coupled receptor superfamily (Chen et al., 2005). GABARs are widely distributed throughout the CNS. There are 19 different combinations of GABAA subunits that have been identified (α1-6, β1-3, γ1-3, δ, ε, π, θ and ρ1-3)(Fig.1)(Barnard et al., 1998). Each subunit is comprised of a large extracellular N-terminus, four transmembrane domains (M1-M4), a large intracellular loop between M3 and M4, and a small extracellular C-terminus (Fig.2,A). There is general concordance that M2 from each of the five subunits lines the pore (Fig.2,B)(Leonard et al., 1988). The prototypical GABAA receptor binds two GABA molecules at the interface between α and β subunits, thereby opening the gate and producing a chloride current across the membrane (Colquhoun and Sivilotti, 2004). Coexpression of only α and β subunits is sufficient to produce functional Cl- channels. The fifth subunit typically provides for receptor modulation by a variety of pharmacologically and clinically relevant drugs which interact with distinct binding sites on the GABAA receptor.

Fig.1.

Table showing the different GABAA/C receptor subunits.

Fig.2.

Ligand-gated ionic channel (LGICs) structure. A. Each GABAA receptor subunit contains four transmembrane domains (TM). B. The TM2 domain forms the wall of the channel pore. C. The majority of native GABAA receptors are composed of 2α, 2β and 1γ subunit.

A majority of native GABAA receptors are thought to be composed of two α, two β and one γ subunit (Chang et al., 1996) in the arrangement γβαβα (Fig.2,C) (McKernan and Whiting, 1996; Sieghart and Sperk, 2002). However, it has been shown that the variability of native receptors might be significantly larger than expected. For instance, each individual receptor complex can contain two different α and two different β isoforms. One study, using quantitative immunoblotting, has suggested the presence of an α1α6β2δ receptor combination in the rat cerebellum (Thompson et al., 1996). It has also been shown that δ, like π and θ, is able to form four-subunit-type pentameric receptor complexes with α, β and γ (αβγδ) (Bonnert et al., 1999). Different receptor combinations can vary in GABA sensitivity, kinetics, and modulation by different ligands. This review will primarily focus on δ-containing GABAA receptors.

Phasic and Tonic GABAA-mediated inhibition

GABAA-mediated synaptic transmission classically refers to the transient ‘phasic’ inhibitory postsynaptic current (IPSC) following activation of synaptic receptors by a high GABA concentration (mM range) (Maconochie et al., 1994; Farrant and Nusser, 2005). A typical response of postsynaptic GABAA receptors lasts less than 50 ms (Cobb et al., 1995; Hardie and Pearce, 2006). Synaptic GABAA receptors are believed to contain the γ subunit, have reduced GABA sensitivity, and are likely insensitive to the low ambient concentrations of GABA throughout the extracellular space (nM range). Synaptic inhibition plays a primary role in information transfer in the CNS, although tonic inhibition occurs before synapse formation in embryonic neurons (Valeyev et al., 1993; Owens et al., 1999; Demarque et al., 2002). In the δ subunit-dense mature cerebellar granule cells, tonic inhibition contributes to nearly 90% of total inhibition (Hamann et al., 2002). Thus, super-sensitive extrasynaptic GABAA receptor subtypes mediate “persistent” tonic inhibition (Walker and Semyanov, 2008).

Functional expression of δ-containing GABAA receptors and their role in tonic inhibition

The nM-μM range concentrations of GABA presumed to be present in the extratracellular space (Saxena and Macdonald, 1996; Wallner et al., 2003), as well as spillover from synaptic GABA, activate extrasynaptic and perisynaptic GABA receptors. It is assumed that a majority of extrasynaptic receptors contain the δ subunit. High GABA sensitivity coupled with a low level of desensitization in the constant presence of ambient GABA concentrations make these receptors ideal for providing tonic inhibition. Less frequently, extrasynaptic receptors may be composed of αβ, α5β3γ2, α1β2γ2 or α3β3γ2 (Nusser et al., 1998; Stell et al., 2003; Belelli and Lambert, 2005; Jia et al., 2005; Mortensen and Smart, 2006).

The δ subunit has been assumed to be predominately co-expressed with α4 and/or α6 subunits. The highest GABA affinity is exhibited by α4β2,3δ or α6β2,3δ combinations, with a GABA EC50 (concentration for half-maximal activation) in the nM range. The α6β2,3δ combination is largely found in cerebellar granular cells (CGCs), which contain the highest CNS density of δ subunits at 30% (Jones et al., 1997; Jechlinger et al., 1998; Nusser et al., 1999; Pirker et al., 2000; Sassoe-Pognetto et al., 2000). The α6β2,3δ receptor complex is almost exclusively found at extrasynaptic locations (Nusser et al., 1999; Sassoe-Pognetto et al., 2000). The second highest level of δ subunit density has been found in granular cells of the dentate gyrus, where most receptors appear to be the α4β2,3δ combination. These receptors localize perisynaptically (Wei et al., 2003) and have consistently been shown to mediate tonic inhibition in Dentate Gyrus Granule Cells (DGGCs) (Nusser and Mody, 2002; Stell et al., 2003; Wei et al., 2004; Maguire et al., 2005; Herd et al., 2008) and CGCs (Stell et al., 2003). The α4β3δ receptor subtype is mainly expressed in the ventro-basal nucleus of the thalamus and neocortex, mediating tonic inhibition in those brain regions (Chen et al., 2005; Cope et al., 2005; Glykys et al., 2007).

It has also been determined that the α5 and δ subunits are the principal GABAA receptor subunits responsible for mediation of tonic inhibition in hippocampal neurons (Glykys et al., 2008). Glykys et al generated α5 and δ double knock-out mice (Gabra5/Gabrd-/-) and recordings from CA1/CA3 Pyramidal Cells (PCs), DGGCs and Molecular Layer (ML) interneurons displayed an absence of tonic currents without compensatory changes in spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs), excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs), or membrane resistance.

It was previously shown that the α4 subunit, the most common partner of δ, is not expressed in ML interneurons, but rather α1 and δ subunits co-localize and most likely form functional receptors with β subunits and underlie the GABAAR-mediated tonic inhibitory current in ML interneurons (Glykys et al., 2007). There are additional reports that α1, β2 and δ subunits may form functional receptors when co-expressed in the same neurons (Mertens et al., 1993; Pirker et al., 2000; Mangan et al., 2005). The α1 subunit has been detected in the extrasynaptic region (Sun et al., 2004; Baude et al., 2007) consistent with the typical localization of δ-containing receptors (Nusser et al., 1998; Farrant and Nusser, 2005). In addition, one recent report has indicated the importance of α1βxδ receptors for tonic inhibition in humans. A significant correlation was illustrated between decreased RNA expression of δ and α1 subunits (but not α4 subunits) in human cortical pyramidal neurons in subjects with schizophrenia (Maldonado-Aviles et al., 2009). Thus, a reduced number of α1βxδ receptors could contribute to the deficient tonic inhibition involved in prefrontal cortical dysfunction that occurs in schizophrenia.

Pharmacological properties of δ-containing GABAA receptors

In addition to high potency and low desensitization, another pharmacological property of αβδ receptors is low efficacy. Although the ubiquitous α4,6β2,3δ combinations exhibit the highest affinity to GABA, they have an Imax three-fold lower than corresponding α4,6β2,3 receptors. For α4β3δ receptors, agonists such as THIP or gabaxadol produced significantly larger chloride currents than GABA, but for α6β3δ-containing receptors, gaboxadol, muscimol, and isoguvacine exhibited even higher relative efficacy and potency levels (Adkins et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2002; Storustovu and Ebert, 2006; Wafford and Ebert, 2006). It appears that GABA is a partial agonist when δ is incorporated into GABAA receptors (Adkins et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2002). It was indicated in several studies that αβδ GABA receptors have a lower open channel probability and mean open time, as well as one less open state, than corresponding αβγ receptors (Fisher and Macdonald, 1997; Akk et al., 2004).

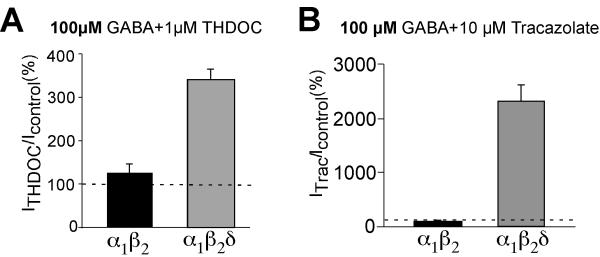

α1β2δ GABA receptors are low efficacy receptors that are nearly unresponsive to saturating concentrations of GABA. We observed a 50-fold decrease in maximum GABA activated currents for α1β2δ receptors compared to α1β2 receptors and a 126-fold decrease in currents compared to α1β2γ2 receptors (equal cRNA levels were injected) (Fig.3). At the same time, the GABA sensitivity for α1β2δ receptors was not significantly lower than that of α1β2 GABA receptors (Zheleznova et al., 2008). Potentiation of these low efficacy, high potency receptors is likely achieved by increasing the efficacy rather than the affinity to GABA. Pharmacological compounds may bolster the efficacy by facilitating and stabilizing receptors in the open state.

Fig.3.

Bar graphs plotting the maximum currents of α1β2 (Imax =2736 ± 306, n=23; black bar), α1β2δ (Imax =55 ± 5, n=39; open bar), α1β2γ2s (Imax =6949±354, n=42; gray bar) and α1β2δ(L9’S)(Imax=4565±372, n=8) GABAA receptors. Compared to α1β2δ, α1β2, α1β2γ2s and α1β2δ (L9’S) show 50-fold, 126-fold and 83-fold increases in the maximum GABAA-activated currents, respectively.

Unlike most of γ subunit-containing GABA receptors, αβδ receptors have a very low sensitivity to benzodiazepines, but are highly sensitive to low concentrations of alcohol (3-30mM)(Mohler, 2006). It has been shown that a global deletion of the δ subunit in the GABAA receptor results in a decrease in the sensitivity of mice to the sedative/hypnotic, anxiolytic, and pro-absence effects of neuroactive steroids (Mihalek et al., 1999; Spigelman et al., 2002).

Neurosteroid regulation

Above all other pharmacological compounds, neurosteroids (including pregnanolone and allopregnanolone) are the most powerful modulators of αβδ-containing GABAA receptors (Adkins et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2002; Wohlfarth et al., 2002). Various neurosteroids have been demonstrated to promote anxiolytic, analgesic, sedative, anticonvulsant and anesthetic effects. There are an extensive number of neurological and psychiatric diseases associated with steroid dysfunctions (Reddy, 2004; Belelli and Lambert, 2005; Eser et al., 2006; Strous et al., 2006; Mitchell et al., 2008).

Neurosteroids are normally present in the intracellular space at the nanomolar concentration range, which is enough to affect δ-containing GABAA receptors, but insufficient to influence synaptic GABA receptors (Stell et al., 2003). Only super-physiological neurosteroid concentrations can affect synaptic γ-containing receptors. Numerous data implicate neurosteroids in αβ receptor modulation. For instance, we have shown that the principal effect of neurosteroids on α1β2 receptors is to increase their sensitivity to GABA (Zheleznova et al., 2008). Wahlfarth et al obtained similar results for α1β3 receptors (Wohlfarth et al., 2002).

Interestingly, the δ subunit is unlikely to be involved in neurosteroid binding. Homology modeling of the neurosteroid binding site in GABAA receptors and site-directed mutagenesis of residues in other subunits (β and γ) suggests that this site is located solely in the α subunit (Hosie et al., 2006). The previously identified residues of the α1 subunit are Q241 (located near the intracellular portion of the TM1 domain), N407, and Y410 (located near the external end of TM4) (Hosie et al., 2009). This binding site is highly conserved throughout the α subunit family (α1-α5). The homology model also accounts for a second putative neurosteroid binding site that is involved in the direct activation of the receptor. This site is activated by super-physiological concentrations of neurosteroids and appears to be located at the αβ interface.

Different endogenous steroids appear to modulate GABAA receptors in two divergent ways, potentiating or inhibiting receptor function depending on the presence of the 3α-hydroxi or 3β-sulfate group of sterol ring. For instance, nanomolar concentrations of THDOC, and allopregnanolone (3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone or THP) increased GABAA receptor currents, whereas low concentrations (micromolar) of pregnanolone sulfate and DHEAS antagonize the receptor (Majewska, 2007). The most efficacious endogenous potentiators of δ-containing GABA receptors are neurosteroids with the 3α-hydroxi ring A-reduced pregnane steroids. It has been proposed that such neurosteroids (THDOC) interact with both lipid membrane and receptor proteins at the protein-lipid interface, stabilizing the open state of the pore (Majewska, 2007). It has also been proposed that the plasma membrane is the most direct and relevant access pathway in neurosteroid interaction with the GABAA receptor (Akk et al., 2005). Concordantly, on a single channel level, THDOC increases the efficacy of the α1β3δ receptor by increasing the duration of channel opening and introducing a new open state (Wohlfarth et al., 2002).

In opposition to this potentiation, THDOC and THP can also inhibit select δ-containing receptors by increasing desensitization in an apparently voltage-dependent manner. For these GABA receptor combinations, an especially strong inhibition was observed for outward chloride currents (Bianchi et al., 2002; Shen et al., 2007).

GABA efficacy and THDOC enhancement of αβδ receptors are critically dependent on the exact subunit composition. For α4,6β2,3δ receptors, maximum GABA currents were amplified by THDOC ≈2.8-fold (Wohlfarth et al., 2002; Meera et al., 2009). It was discovered by comparing α1β3δ and α6β3δ GABA receptor currents that δ-containing GABA receptors can be potentiated by THDOC to a greater extent when δ is in combination with the α1 subunit (Wohlfarth et al., 2002). THDOC augmented maximum GABA currents of α1β2δ receptors by 3.4 fold (Zheleznova et al., 2008). The highest degree of potentiation was reported for the α1β3δ receptor, which was potentiated by a factor of ≈10-17 fold by THDOC at saturating concentrations of GABA (Bianchi et al., 2002; Wohlfarth et al., 2002; Kaur et al., 2009).

In addition to the increase in the maximum GABA-elicited current, there are noticeable changes in the kinetics of the αβδ GABAA receptor produced by THDOC. Normally, a mildly-desensitizing and rapidly-deactivating receptor becomes highly-desensitizing, slowly-deactivating. This effect could be explained if neurosteroids modify the gating behavior of the αβδ receptors by allowing entry into a typically unavailable desensitized state (Wohlfarth et al., 2002).

Tracazolate potentiation

A unique group of anxiolytic and anticonvulsive agents, pyrazolopyridines, (i.e. tracazolate, etazolate and cartazolate) are powerful potentiators of δ-containing GABAA receptors (Young et al., 1987; Thompson et al., 2002), although the binding site of parazolopyridines has yet to be identified. The δ subunit is unlikely critical for pyrazolopyridine binding in GABAA receptors, although receptors containing the δ subunit are much more sensitive to pyrazolopyridines. Pyrazolopyridines are less potent than benzodiazepines in modulating αβγ receptors, generally producing a slight leftward shift in the GABA dose response curve. In contrast to αβδ receptors, high concentrations of pyrazolopyridines slightly inhibit chloride currents from αβ and αβγ receptors. Perhaps pyrazolopyridines have a higher affinity for the desensitized state in these receptors (Thompson et al., 2002; Khom et al., 2006).

Tracazolate potentiates GABA-induced currents for δ-containing receptors beyond the maximum for GABA alone. For example, tracazolate enhanced GABA maximum currents for α2β3δ receptors nearly three-fold (Yang et al., 2005). The α1β3δ potentiation by tracazolate at an EC20 GABA concentration was nearly 14-fold higher than GABA alone and 3-fold higher than maximal GABA currents, yet no significant effect on the GABA dose-response relation (Thompson et al., 2002).

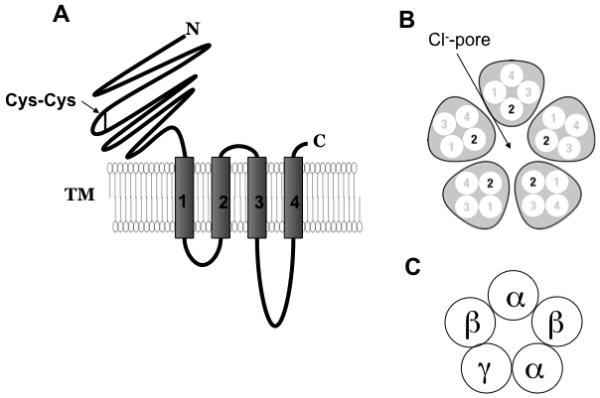

Tracazolate enhanced the current amplitude for α1β2δ in the presence of saturating GABA concentrations even more than THDOC (23-fold increase by tracazolate and 3.4-fold increase by THDOC, Fig.4). On the contrary, α1β2 and α1β2γ3 receptors exhibited no increase in the maximum current amplitude in the presence of tracazolate at saturating GABA concentrations. We observed an increase in the current amplitude for α1β2 and α1β2γ2 receptors by tracazolate only at low GABA concentrations due to a leftward displacement in the dose-response curve (Zheleznova et al., 2008). Similar results have been obtained for α1β3γ2 (Thompson et al., 2002) and α1β3γ1,2 receptors (Khom et al., 2006).

Fig.4.

The fold increase by THDOC (A) and tracazolate (B) is shown with a saturating concentration of GABA (100 μM) from oocytes expressing α1β2 (black bar) and α1β2δ (gray bar) GABAA receptors.

The logical explanation of these findings is similar to that for THDOC; tracazolate restores the GABA efficacy of α1β2δ receptors by increasing the open state probability of the channel. Indeed, tracazolate enhanced the GABA-induced maximum current amplitude nearly 25-fold, on level with the α1β2 receptor maximum amplitude (Fig.4)(Zheleznova et al., 2008). Tracazolate was not able to augment maximal GABA-activated current amplitudes for α1β2 and α1β2γ2 receptors, likely because these receptors were already at maximum efficacy. Mutation of the 9′ leucine residue (L286S) within the second transmembrane domain has been found to facilitate the receptor open state (Chang et al., 1996; Bianchi and Macdonald, 2001). When we introduced this mutation in the δ subunit, it restored the gating efficacy of α1β2δ(L286S) receptors and profoundly increased GABA-mediated current amplitudes (Fig.3). As might be expected, tracazolate did not increase the efficacy of these mutant receptors (Zheleznova et al., 2008).

Conclusion

GABAA receptors are formed by co-assembly of subunits from a large multigene family, and are differentially expressed throughout the brain. This heterogeneous expression provides a unique profile of physiological and pharmacological properties of GABA receptors. For the regions expressing extrasynaptic α1β2δ receptors, the level of basal inhibition could be increased by multiple factors due to potentiation of these receptors by endogenous neurosteroids that increase their response to ambient GABA levels. This presents a unique mechanism for recruiting inhibition without the cost of receptor trafficking to the surface or the activation of intracellular signaling cascades and may play an important role in the modulation and potential silencing of certain neuronal circuits. Unlike the most common α4β2/3δ or α6β2/3δ combinations that are constantly active at nM GABA concentrations, the α1β2δ receptor would be essentially silent even at saturating concentrations of GABA due to its very low efficacy. However, under the influence of THDOC or tracazolate, this receptor combination could exert a profound inhibitory influence on excitability in the CNS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adkins CE, Pillai GV, Kerby J, Bonnert TP, Haldon C, McKernan RM, Gonzalez JE, Oades K, Whiting PJ, Simpson PB. alpha4beta3delta GABA(A) receptors characterized by fluorescence resonance energy transfer-derived measurements of membrane potential. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38934–38939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Bracamontes J, Steinbach JH. Activation of GABA(A) receptors containing the alpha4 subunit by GABA and pentobarbital. J Physiol. 2004;556:387–399. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Shu HJ, Wang C, Steinbach JH, Zorumski CF, Covey DF, Mennerick S. Neurosteroid access to the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11605–11613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4173-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard EA, Skolnick P, Olsen RW, Mohler H, Sieghart W, Biggio G, Braestrup C, Bateson AN, Langer SZ. International Union of Pharmacology. XV. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors: classification on the basis of subunit structure and receptor function. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:291–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baude A, Bleasdale C, Dalezios Y, Somogyi P, Klausberger T. Immunoreactivity for the GABAA receptor alpha1 subunit, somatostatin and Connexin36 distinguishes axoaxonic, basket, and bistratified interneurons of the rat hippocampus. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:2094–2107. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MT, Haas KF, Macdonald RL. Alpha1 and alpha6 subunits specify distinct desensitization, deactivation and neurosteroid modulation of GABA(A) receptors containing the delta subunit. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:492–502. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MT, Macdonald RL. Mutation of the 9′ leucine in the GABA(A) receptor gamma2L subunit produces an apparent decrease in desensitization by stabilizing open states without altering desensitized states. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:737–744. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnert TP, McKernan RM, Farrar S, le Bourdelles B, Heavens RP, Smith DW, Hewson L, Rigby MR, Sirinathsinghji DJ, Brown N, Wafford KA, Whiting PJ. theta, a novel gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9891–9896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N, Kerby J, Bonnert TP, Whiting PJ, Wafford KA. Pharmacological characterization of a novel cell line expressing human alpha(4)beta(3)delta GABA(A) receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:965–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Wang R, Barot S, Weiss DS. Stoichiometry of a recombinant GABAA receptor. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5415–5424. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05415.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Li HZ, Ye N, Zhang J, Wang JJ. Role of GABAB receptors in GABA and baclofen-induced inhibition of adult rat cerebellar interpositus nucleus neurons in vitro. Brain Res Bull. 2005;67:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb SR, Buhl EH, Halasy K, Paulsen O, Somogyi P. Synchronization of neuronal activity in hippocampus by individual GABAergic interneurons. Nature. 1995;378:75–78. doi: 10.1038/378075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Sivilotti LG. Function and structure in glycine receptors and some of their relatives. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope DW, Hughes SW, Crunelli V. GABAA receptor-mediated tonic inhibition in thalamic neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11553–11563. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3362-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarque M, Represa A, Becq H, Khalilov I, Ben-Ari Y, Aniksztejn L. Paracrine intercellular communication by a Ca2+- and SNARE-independent release of GABA and glutamate prior to synapse formation. Neuron. 2002;36:1051–1061. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eser D, Schule C, Baghai TC, Romeo E, Rupprecht R. Neuroactive steroids in depression and anxiety disorders: clinical studies. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84:244–254. doi: 10.1159/000097879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JL, Macdonald RL. Single channel properties of recombinant GABAA receptors containing gamma 2 or delta subtypes expressed with alpha 1 and beta 3 subtypes in mouse L929 cells. J Physiol. 1997;505(Pt 2):283–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.283bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Mann EO, Mody I. Which GABA(A) receptor subunits are necessary for tonic inhibition in the hippocampus? J Neurosci. 2008;28:1421–1426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4751-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Peng Z, Chandra D, Homanics GE, Houser CR, Mody I. A new naturally occurring GABA(A) receptor subunit partnership with high sensitivity to ethanol. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:40–48. doi: 10.1038/nn1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann M, Rossi DJ, Attwell D. Tonic and spillover inhibition of granule cells control information flow through cerebellar cortex. Neuron. 2002;33:625–633. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie JB, Pearce RA. Active and passive membrane properties and intrinsic kinetics shape synaptic inhibition in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8559–8569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0547-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd MB, Haythornthwaite AR, Rosahl TW, Wafford KA, Homanics GE, Lambert JJ, Belelli D. The expression of GABAA beta subunit isoforms in synaptic and extrasynaptic receptor populations of mouse dentate gyrus granule cells. J Physiol. 2008;586:989–1004. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Clarke L, da Silva H, Smart TG. Conserved site for neurosteroid modulation of GABA A receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HM, Smart TG. Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature. 2006;444:486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature05324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jechlinger M, Pelz R, Tretter V, Klausberger T, Sieghart W. Subunit composition and quantitative importance of hetero-oligomeric receptors: GABAA receptors containing alpha6 subunits. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2449–2457. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02449.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia F, Pignataro L, Schofield CM, Yue M, Harrison NL, Goldstein PA. An extrasynaptic GABAA receptor mediates tonic inhibition in thalamic VB neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:4491–4501. doi: 10.1152/jn.00421.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Korpi ER, McKernan RM, Pelz R, Nusser Z, Makela R, Mellor JR, Pollard S, Bahn S, Stephenson FA, Randall AD, Sieghart W, Somogyi P, Smith AJ, Wisden W. Ligand-gated ion channel subunit partnerships: GABAA receptor alpha6 subunit gene inactivation inhibits delta subunit expression. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1350–1362. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01350.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur KH, Baur R, Sigel E. Unanticipated structural and functional properties of delta-subunit-containing GABAA receptors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7889–7896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806484200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khom S, Baburin I, Timin EN, Hohaus A, Sieghart W, Hering S. Pharmacological properties of GABAA receptors containing gamma1 subunits. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:640–649. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard RJ, Labarca CG, Charnet P, Davidson N, Lester HA. Evidence that the M2 membrane-spanning region lines the ion channel pore of the nicotinic receptor. Science. 1988;242:1578–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.2462281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maconochie DJ, Zempel JM, Steinbach JH. How quickly can GABAA receptors open? Neuron. 1994;12:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire JL, Stell BM, Rafizadeh M, Mody I. Ovarian cycle-linked changes in GABA(A) receptors mediating tonic inhibition alter seizure susceptibility and anxiety. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:797–804. doi: 10.1038/nn1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska MD. Steroids and ion channels in evolution: from bacteria to synapses and mind. Evolutionary role of steroid regulation of GABA(A) receptors. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2007;67:219–233. doi: 10.55782/ane-2007-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Aviles JG, Curley AA, Hashimoto T, Morrow AL, Ramsey AJ, O’Donnell P, Volk DW, Lewis DA. Altered markers of tonic inhibition in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:450–459. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08101484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan PS, Sun C, Carpenter M, Goodkin HP, Sieghart W, Kapur J. Cultured Hippocampal Pyramidal Neurons Express Two Kinds of GABAA Receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:775–788. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.007385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKernan RM, Whiting PJ. Which GABAA-receptor subtypes really occur in the brain? Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meera P, Olsen RW, Otis TS, Wallner M. Etomidate, propofol and the neurosteroid THDOC increase the GABA efficacy of recombinant alpha4beta3delta and alpha4beta3 GABA A receptors expressed in HEK cells. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens S, Benke D, Mohler H. GABAA receptor populations with novel subunit combinations and drug binding profiles identified in brain by alpha 5- and delta-subunit-specific immunopurification. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5965–5973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalek RM, Banerjee PK, Korpi ER, Quinlan JJ, Firestone LL, Mi ZP, Lagenaur C, Tretter V, Sieghart W, Anagnostaras SG, Sage JR, Fanselow MS, Guidotti A, Spigelman I, Li Z, DeLorey TM, Olsen RW, Homanics GE. Attenuated sensitivity to neuroactive steroids in gamma-aminobutyrate type A receptor delta subunit knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12905–12910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell EA, Herd MB, Gunn BG, Lambert JJ, Belelli D. Neurosteroid modulation of GABAA receptors: molecular determinants and significance in health and disease. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:588–595. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler H. GABA(A) receptor diversity and pharmacology. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:505–516. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen M, Smart TG. Extrasynaptic alphabeta subunit GABAA receptors on rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2006;577:841–856. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.117952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Ahmad Z, Tretter V, Fuchs K, Wisden W, Sieghart W, Somogyi P. Alterations in the expression of GABAA receptor subunits in cerebellar granule cells after the disruption of the alpha6 subunit gene. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1685–1697. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Mody I. Selective modulation of tonic and phasic inhibitions in dentate gyrus granule cells. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2624–2628. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.5.2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Somogyi P. Segregation of different GABAA receptors to synaptic and extrasynaptic membranes of cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1693–1703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01693.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DF, Liu X, Kriegstein AR. Changing properties of GABA(A) receptor-mediated signaling during early neocortical development. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:570–583. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.2.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G. GABA(A) receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101:815–850. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS. Pharmacology of catamenial epilepsy. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2004;26:547–561. doi: 10.1358/mf.2004.26.7.863737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassoe-Pognetto M, Panzanelli P, Sieghart W, Fritschy JM. Colocalization of multiple GABA(A) receptor subtypes with gephyrin at postsynaptic sites. J Comp Neurol. 2000;420:481–498. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000515)420:4<481::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena NC, Macdonald RL. Properties of putative cerebellar gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor isoforms. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:567–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Gong QH, Aoki C, Yuan M, Ruderman Y, Dattilo M, Williams K, Smith SS. Reversal of neurosteroid effects at alpha4beta2delta GABAA receptors triggers anxiety at puberty. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:469–477. doi: 10.1038/nn1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W, Sperk G. Subunit composition, distribution and function of GABA(A) receptor subtypes. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:795–816. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spigelman I, Li Z, Banerjee PK, Mihalek RM, Homanics GE, Olsen RW. Behavior and physiology of mice lacking the GABAA-receptor delta subunit. Epilepsia. 2002;43(Suppl 5):3–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.43.s.5.8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stell BM, Brickley SG, Tang CY, Farrant M, Mody I. Neuroactive steroids reduce neuronal excitability by selectively enhancing tonic inhibition mediated by delta subunit-containing GABAA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14439–14444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2435457100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storustovu SI, Ebert B. Pharmacological characterization of agonists at delta-containing GABAA receptors: Functional selectivity for extrasynaptic receptors is dependent on the absence of gamma2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:1351–1359. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strous RD, Kupchik M, Roitman S, Schwartz S, Gonen N, Mester R, Weizman A, Spivak B. Comparison between risperidone, olanzapine, and clozapine in the management of chronic schizophrenia: a naturalistic prospective 12-week observational study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:235–243. doi: 10.1002/hup.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Sieghart W, Kapur J. Distribution of alpha1, alpha4, gamma2, and delta subunits of GABAA receptors in hippocampal granule cells. Brain Res. 2004;1029:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CL, Pollard S, Stephenson FA. Developmental regulation of expression of GABAA receptor alpha 1 and alpha 6 subunits in cultured rat cerebellar granule cells. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1337–1346. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SA, Wingrove PB, Connelly L, Whiting PJ, Wafford KA. Tracazolate reveals a novel type of allosteric interaction with recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:861–869. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.4.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeyev AY, Cruciani RA, Lange GD, Smallwood VS, Barker JL. Cl- channels are randomly activated by continuous GABA secretion in cultured embryonic rat hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 1993;155:199–203. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90707-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wafford KA, Ebert B. Gaboxadol--a new awakening in sleep. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MC, Semyanov A. Regulation of excitability by extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2008;44:29–48. doi: 10.1007/400_2007_030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner M, Hanchar HJ, Olsen RW. Ethanol enhances alpha 4 beta 3 delta and alpha 6 beta 3 delta gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors at low concentrations known to affect humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15218–15223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2435171100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Faria LC, Mody I. Low ethanol concentrations selectively augment the tonic inhibition mediated by delta subunit-containing GABAA receptors in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8379–8382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2040-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Zhang N, Peng Z, Houser CR, Mody I. Perisynaptic localization of delta subunit-containing GABA(A) receptors and their activation by GABA spillover in the mouse dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10650–10661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10650.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfarth KM, Bianchi MT, Macdonald RL. Enhanced neurosteroid potentiation of ternary GABA(A) receptors containing the delta subunit. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1541–1549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01541.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Jones BL, Henderson LP. Role of the alpha subunit in the modulation of GABA(A) receptors by anabolic androgenic steroids. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:300–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R, Urbancic A, Emrey TA, Hall PC, Metcalf G. Behavioral effects of several new anxiolytics and putative anxiolytics. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;143:361–371. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheleznova N, Sedelnikova A, Weiss DS. alpha1beta2delta, a silent GABAA receptor: recruitment by tracazolate and neurosteroids. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1062–1071. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]