Abstract

Inflammatory phenomena appear to contribute to the occurrence of perinatal cerebral white matter damage and cerebral palsy (CP). The stimulus that initiates the inflammation remains obscure. 1246 infants born before the 28th post-menstrual week had a protocol ultrasound scan of the brain read concordantly by two independent sonologists. 899 of the children had a neurologic examination at approximately 24 months post term equivalent. The placenta of each child had been biopsied under sterile conditions, and later cultured. Histologic slides of the placenta were examined specifically for this study. Recovery of a single microorganism predicted an echolucent lesion, whereas polymicrobial cultures and recovery of skin flora predicted both ventriculomegaly and an echolucent lesion. Diparetic CP was predicted by recovery of a single microorganism, multiple organisms, and skin flora. Histologic inflammation predicted ventriculomegaly and diparetic CP. The risk of ventriculomegaly associated with organism recovery was heightened when accompanied by histologic inflammation, but the risk of diparetic CP was not. Low virulence microorganisms isolated from the placenta, including common skin microflora, predict ultrasound lesions of the brain and diparetic CP in the very preterm infant. Organism recovery does not appear to be needed for placenta inflammation to predict diparetic CP.

Infants born long before term are at increased risk of motor, attention, cognitive, and executive function impairments (1–3). Some of the increased risk appears to be due to cerebral white matter damage evident on brain ultrasound scans (4). The damage takes two forms, an echolucent (hypoechoic) lesion (also known as periventricular leukomalacia), considered evidence of focal or multi-focal disease, and late ventriculomegaly, considered evidence of diffuse white matter damage.

Postnatal bacteremia appears to contribute to the occurrence of diffuse white matter damage (5–7), and later neurodevelopmental disabilities (7–9). Because preterm newborns who die with white matter damage very rarely have a microorganism in the brain (10), a circulating, non-infectious messenger originating at the site of microorganism colonization that can then gain access to the brain might account for the brain damage associated with bacteremia (11).

Might a similar process occur before birth? Introducing E. coli into the uterus late in gestation increases the likelihood of white matter damage in the fetal rabbit (12,13) and rat (14,15), even though E. coli are not present in the brain. Introduction of non-infectious endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide) can also produce fetal white matter damage (16–18). Thus, an inflammation-promoting stimulus in the uterus can, without infecting the fetal brain, promote processes that lead to brain damage.

Intrauterine inflammatory processes also appear to increase the risk of white matter damage and cerebral palsy (CP) in the human infant born very preterm (19,20). Only indirect evidence supports the hypothesis that microorganisms isolated from the uterus increase the risk of white matter damage in extremely preterm infants (21–25). We now provide direct support.

Methods

Additional details about the methods can be found in supplementary material (http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX).

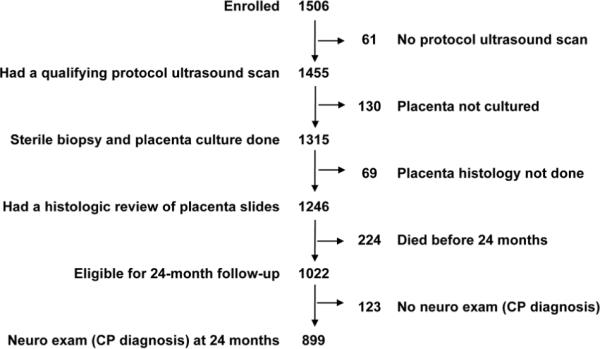

The ELGAN study was designed to identify characteristics and exposures that increase the risk of structural and functional neurologic disorders in ELGANs (the acronym for Extremely Low Gestational Age Newborns). During the years 2002–2004, 1249 mothers who gave birth to 1506 infants before the 28th week (1007 singletons, 414 twins, 77 triplets, 2 quadruplets, and 6 septuplets) consented to participate (Figure 1). The informed consent procedures and documents were approved by everyone of the 14 institutions that enrolled families for this study.

Figure 1.

Sample description

The sample for the brain ultrasound component of this report consists of the 1246 infants (83%) whose placenta was biopsied under sterile conditions for cultures and submitted for histologic evaluation and who had one or more sets of protocol ultrasound scans of the brain read concordantly by two independent sonologists. The sample for the CP component is limited to the 899 children (88% of 1022 survivors) who also had a neurologic examination at 24 months post-term equivalent.

The gestational age estimates were based on a hierarchy of the quality of available information. Most desirable were estimates based on the dates of embryo retrieval or intrauterine insemination or fetal ultrasound before the 14th week (62%). When these were not available, reliance was placed sequentially on a fetal ultrasound at 14 or more weeks (29%), the first day of the last menstrual period (7%), and gestational age recorded in the log of the neonatal intensive care unit (1%).

Protocol scans

Ultrasound studies included six standard quasicoronal views and five sagittal views using the anterior fontanel as the sonographic window (26). The three sets of protocol scans were defined by the postnatal day on which they were obtained (1: days 1–4; 2: days 5–14; 3: day 15- week 40). Details about the procedure and observer variability minimization efforts are presented elsewhere (27).

Placentas

The microbiologic procedures are described in detail elsewhere (28), as are details about histologic procedures (29).

24-month developmental assessment

Procedures to standardize the neurological examination and minimize examiner variability are presented elsewhere (30). The topographic diagnosis of CP (quadriparesis, diparesis, or hemiparesis) was based on an algorithm using these data (31)

Data analysis

We evaluated the following generalized null hypotheses: 1) the risk of an ultrasound lesion of the brain or a CP diagnosis is not associated with the recovery of microorganisms from placenta parenchyma. 2) The risk of an ultrasound lesion of the brain or a CP diagnosis is not associated with any histologic lesion of the placenta. 3) Microorganisms need not elicit histologic inflammation of the placenta to predict an abnormality on an ultrasound scan of the brain, or a CP diagnosis.

In both the ultrasound-assessed sample (N=1246) and in the developmentally assessed sample (N=899), placentas delivered vaginally were more likely than placentas delivered by Cesarean section to harbor a microorganism. Consequently, we evaluated our hypotheses first in the entire sample (Table 1), and then in the sub-samples of vaginal and cesarean section deliveries (Table 2 for ultrasound lesions and Table 3 for CP diagnoses).

Table 1.

Sample description. These are the numbers of children who had the characteristics listed at the top of each row and in the left-hand column‡.

| Vaginal deliveries | Cesarean section | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age → | 23–24 | 25–26 | 27 | N | 23–24 | 25–26 | 27 | N |

| Microorganism | ||||||||

| Any aerobe | 53 | 55 | 38 | 146 | 30 | 63 | 43 | 136 |

| Any anaerobe | 41 | 52 | 35 | 128 | 36 | 59 | 31 | 126 |

| Any Mycoplasma | 15 | 18 | 14 | 47 | 10 | 19 | 14 | 43 |

| # of species: 0 | 17 | 59 | 28 | 104 | 47 | 164 | 148 | 359 |

| 1 | 21 | 23 | 19 | 63 | 23 | 72 | 55 | 150 |

| 2+ | 46 | 55 | 36 | 137 | 30 | 38 | 18 | 86 |

| Skin flora* | 33 | 37 | 31 | 101 | 15 | 32 | 28 | 75 |

| Vagina flora§ | 29 | 29 | 26 | 84 | 16 | 34 | 9 | 59 |

| Histology | ||||||||

| Inflammation | ||||||||

| Chorionic plate¶ | 31 | 48 | 22 | 101 | 20 | 32 | 20 | 72 |

| Chorion/decidua# | 48 | 77 | 42 | 167 | 34 | 78 | 40 | 152 |

| Fetal stem vessel | 29 | 58 | 34 | 121 | 25 | 57 | 25 | 107 |

| Umbilical cord† | 15 | 36 | 20 | 71 | 16 | 40 | 18 | 74 |

| Thrombosis FSV | 5 | 7 | 7 | 19 | 1 | 13 | 12 | 26 |

| Infarct | 12 | 21 | 16 | 49 | 13 | 47 | 54 | 111 |

| ↑ syncytial knots | 12 | 14 | 11 | 37 | 19 | 56 | 71 | 146 |

| Decidual depostn | 30 | 32 | 14 | 76 | 15 | 34 | 20 | 69 |

| Delivery initiator | ||||||||

| Preterm labor | 54 | 78 | 43 | 175 | 43 | 100 | 89 | 232 |

| PPROM | 14 | 36 | 29 | 79 | 18 | 53 | 41 | 112 |

| Preeclampsia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 56 | 52 | 117 |

| Abruption | 11 | 10 | 6 | 27 | 15 | 36 | 20 | 71 |

| Cx insufficiency | 4 | 9 | 3 | 16 | 12 | 15 | 3 | 30 |

| Fetal indication | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 14 | 16 | 33 |

| Outcomes | ||||||||

| Ventriculomegaly | 14 | 12 | 8 | 34 | 12 | 30 | 15 | 57 |

| Echolucency | 11 | 17 | 3 | 31 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 32 |

| Cerebral palsy | ||||||||

| Quadriparesis | 10 | 10 | 2 | 22 | 13 | 8 | 10 | 31 |

| Diparesis | 10 | 5 | 3 | 18 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 15 |

| Hemiparesis | 5 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 9 |

| Maximum column N | 84 | 137 | 83 | 304 | 100 | 274 | 221 | 595 |

Abbreviations and qualifiers are identified at the bottom of the following tables

Table 2.

Odds ratios (and 95% CI) of two ultrasound lesions (ventriculomegaly and an echolucent white matter lesion) and three cerebral palsy diagnoses (quadriparesis, diparesis, and hemiparesis) associated with each placental organism or group of organisms listed on the left. These data are from the total sample. The only adjustment is for gestational age (23–24, 25–26, and 27 weeks).

| Ultrasound lesion | Type of cerebral palsy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microorganism | Ventriculomegaly | Echolucent lesion | Quadriparesis | Diparesis | Hemiparesis |

| Any aerobe | 1.7 (1.2, 2.4) | 1.5 (1.01, 2.4) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.8) | 4.0 (1.9, 8.6) | 0.6 (0.2, 2.0) |

| Any anaerobe | 1.5 (1.02, 2.1) | 1.3 (0.9, 2.1) | 1.9 (1.1, 3.4) | 1.7 (0.8, 3.4) | 1.0 (0.3, 2.9) |

| Any Mycoplasma | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) | 1.1 (0.6, 2.1) | 0.9 (0.3, 2.3) | 2.2 (0.9, 5.3) | 0.5 (0.1, 4.1) |

| # of species: 1 | 1.5 (0.9, 2.3) | 1.8 (1.1, 3.0) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.6) | 3.4 (1.2, 9.6) | 0.6 (0.2, 2.3) |

| 2+ | 1.9 (1.2, 2.8) | 1.9 (1.1, 3.1) | 2.3 (1.2, 4.4) | 5.2 (2.0, 14) | 0.8 (0.2, 2.5) |

| Skin flora* | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5) | 2.1 (1.3, 2.2) | 1.4 (0.7, 2.7) | 2.5 (1.2, 5.2) | 0.3 (0, 2.0) |

| Vaginal flora§ | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.7) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.3) | 0.3 (0, 2.2) |

Corynebacterium sp, Propionebacterium sp, Staphylococcus sp

Prevotella bivia, Lactobacillus sp, Peptostreptococcus magnus, Gardnerella vaginalis

Table 3.

Odds ratios (and 95% CI) of ventriculomegaly and an echolucent white matter lesion associated with each placental organism or group of organisms listed on the left in the vaginal and Cesarean section delivery subsamples. The only adjustment is for gestational age (23–24, 25–26, and 27 weeks).

| Ventriculomegaly | Echolucent lesion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microorganism | Vaginal | Cesarean | Vaginal | Cesarean |

| Any aerobe | 1.7 (0.98, 3.0) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.4) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.7) | 1.9 (1.04, 3.6) |

| Any anaerobe | 1.2 (0.7, 2.0) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.6) | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | 1.4 (0.7, 2.7) |

| Any Mycoplasma | 1.0 (0.5, 1.9) | 0.8 (0.3, 2.0) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.7) | 1.5 (0.6, 4.0) |

| # of species: 1 | 1.9 (0.9, 4.2) | 1.2 (0.7, 2.2) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.3) | 2.0 (1.01, 3.9) |

| 2+ | 1.8 (0.9, 3.5) | 1.9 (1.02, 3.4) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.5) | 2.0 (0.9, 2.4) |

| Skin flora* | 1.5 (0.9, 2.5) | 1.8 (0.99, 3.2) | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | 3.5 (1.8, 6.7) |

| Vaginal flora§ | 1.1 (0.6, 1.9) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.9) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.4) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.2) |

Corynebacterium sp, Propionebacterium sp, Staphylococcus sp

Prevotella bivia, Lactobacillus sp, Peptostreptococcus magnus, Gardnerella vaginalis

Because ultrasound characteristics tended to occur together, we compared the placentas of infants whose ultrasound scans had a lesion to those of the 975 infants whose scans showed no abnormality.

We created multivariable models to identify the contribution of relevant characteristics and exposures to the outcome of interest. Their contributions are presented as risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The only potential cofounders that modified the risk ratios were categories of gestational age (23–24, 25–26, 27 weeks). Therefore, we adjusted for these variables only.

Because the CP diagnoses are mutually exclusive and each is appropriately compared to the same group of children without any CP diagnosis, we used multinomial logistic regression for analyses presented in Tables 2 and 4. The logistic regression analyses for Table 5, however, are not multinomial because the comparison group for each diagnosis consists of children whose placenta neither harbored an organism nor had histologic inflammation.

Table 4.

Odds ratios (and 95% CI) of a CP diagnosis of quadriparesis or diparesis associated with each placental organism or group of organisms listed on the left in the vaginal and Cesarean section delivery subsamples. The only adjustment is for gestational age (23–24, 25–26, and 27 weeks).

| Quadriparesis | Diparesis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microorganism | Vaginal | Cesarean | Vaginal | Cesarean |

| Any aerobe | 1.3 (0.5, 3.2) | 1.8 (0.8, 4.0) | 5.1 (1.4, 18) | 3.0 (1.03, 8.5) |

| Any anaerobe | 2.8 (1.1, 7.0) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.2) | 3.0 (1.1, 8.5) | 0.4 (0.1, 2.0) |

| Any Mycoplasma | 0.8 (0.2, 2.8) | 0.9 (0.2, 4.0) | 0.9 (0.3, 3.5) | 4.7 (1.4, 16) |

| # of species: 1 | 0.8 (0.3, 2.5) | 0.8 (0.2, 3.3) | 1.1 (0.3, 3.9) | 0.3 (0, 2.7) |

| 2+ | 2.5 (0.5, 14) | 1.9 (0.3, 11) | 2.0 (0.3, 15) | 7.8 (0.6, 98) |

| Skin flora* | 1.5 (0.6, 3.7) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.5) | 3.1 (1.1, 8.5) | 1.0 (0.2, 4.6) |

| Vaginal flora§ | 1.5 (0.6, 3.8) | 1.2 (0.4, 3.7) | 1.2 (0.4, 3.3) | 1.3 (0.3, 6.3) |

Corynebacterium sp, Propionebacterium sp, Staphylococcus sp

Prevotella bivia, Lactobacillus sp, Peptostreptococcus magnus, Gardnerella vaginalis

Table 5.

Odds ratios (and 95% CI) of two ultrasound lesions (ventriculomegaly and an echolucent white matter lesion) and three cerebral palsy diagnoses (quadriparesis, diparesis, and hemiparesis) associated with each placenta histologic characteristic listed on the left. These data are from the total sample. The only adjustment is for gestational age (23–24, 25–26, and 27 weeks).

| Ultrasound lesion | Type of cerebral palsy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microorganism | Ventriculomegaly | Echolucent lesion | Quadriparesis | Diparesis | Hemiparesis |

| Inflammation chorionic plate¶ | 1.5 (1.02, 2.3) | 1.6 (0.97, 2.5) | 1.6 (0.9, 3.0) | 2.3 (1.1, 4.8) | 2.2 (0.8, 6.1) |

| Inflammation chorion/decidua§ | 1.4 (1.01, 2.4) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.0) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.9) | 3.4 (1.6, 7.4) | 1.2 (0.5, 3.2) |

| Neutrophils in fetal stem vessls | 1.4 (0.99, 2.1) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.1) | 1.4 (0.8, 2.8) | 1.7 (0.8, 3.7) | 1.3 (0.4, 3.7) |

| Umbilical cord vasculitis† | 1.4 (0.9, 2.2) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.5) | 1.5 (0.8, 3.0) | 1.7 (0.8, 3.5) | 0.8 (0.3, 2.6) |

| Thrombosis fetal stem vessels | 2.1 (1.2, 3.9) | 1.6 (0.7, 3.4) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.7) | 1.9 (0.8, 4.3) | 1.6 (0.5, 5.2) |

| Infarct | 0.5 (0.3, 0.96) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.8) | 1.9 (0.6, 5.5) | 1.5 (0.3, 6.6) | 1.4 (0.2, 11) |

| Increased syncytial knots | 0.7 (0.5, 1.2) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.5) | 1.7 (0.9, 3.5) | 0.7 (0.2, 2.1) | 1.1 (0.3, 3.9) |

| Decidual hem/fibrin deposition | 1.0 (0.6, 1.5) | 1.7 (1.03, 2.8) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.0) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.5) | 0.3 (0, 2.0) |

stage 3 and severity 3

grades 3 and 4

grades 3, 4 and 5

Results

Placenta microbiology

Infants whose placenta harbored an aerobe or an anaerobe were at increased risk of ventriculomegaly, as were infants whose placenta harbored more than one organism or an organism considered part of normal skin flora (Table 1). Similar to ventriculomegaly, an echolucent lesion was associated with recovery of an aerobe, multiple organisms, and an organism considered part of normal skin flora. In contrast to ventriculomegaly, however, an echolucent lesion was associated with single organism cultures, but not with recovery of an anaerobe.

Largely, vaginal and cesarean section sub-samples provided similar information about associations between bacteria recovered from the placenta and ventriculomegaly (Table 2). On the other hand, much of the association between recovery of bacteria and an echolucent lesion in the cerebral white matter reflects the contribution of the Cesarean section sub-sample. Statistical insignificance in the subsamples and significance in the total sample is a consequence of the consistent direction of the odds ratios in the subsamples, and of the larger size of the total sample.

The only individual organism associated with increased risk of ventriculomegaly in infants delivered vaginally, as well as in those delivered by Cesarean section, was Actinomyces species (sp) (Table S1, http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX). Only in infants delivered vaginally was Corynebacterium species associated with an increased risk of ventriculomegaly. In contrast, an echolucent lesion was associated with recovery of Propionibacterium sp, non-aureus Staphylococcus sp, and Gardnerella vaginalis, but only in the Cesarean section sub-sample (Table S2, http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX).

In the total sample, the risk of quadriparesis was increased if an anaerobe or multiple organisms were recovered from the placenta (Table 1). The odds of diparesis, on the other hand, was increased if the placenta harbored an aerobe, a single organism, multiple organisms, or an organism considered part of normal skin flora. Hemiplegic CP was not associated with any organism.

The vaginal sub-sample contributed appreciably to the associations seen in the total sample for quadriparetic and diparetic CP (Table 3). In the Cesarean section delivered subsample, the association between quadriparetic CP and an anaerobe was hardly evident, while the association between quadriparetic CP and polymicrobial infections was less prominent than in the vaginal sub-sample. In contrast, Cesarean section delivered placentas provide much of the information about the increased risk of diparesis associated with Mycoplasma sp, polymicrobial infections, and none of the information about an increased risk associated with skin organisms.

Diparesis was associated with recovery of Corynebacterium species and non-aureus Staphylococcus in the total sample (Table S3, http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX). The association between Corynebacterium species and diparesis was statistically significant only among vaginally delivered placenta/child dyads (Table S4, http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX). Among those delivered by Cesarean section, diparesis was statistically significantly associated with both alpha hemolytic Streptococcus and Mycoplasma sp (Table S5, http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX).

Placenta histologic characteristics

Inflammation of the chorionic plate and the chorion/decidua, and thrombosis of the fetal stem vessels were associated with increased risk of ventriculomegaly, while a placenta infarct was associated with reduced risk (Table 3). An echolucent lesion, on the other hand, was associated only with decidual hemorrhage and fibrin deposition considered indicative of abruption. Vaginal and Cesarean section delivered placentas conveyed similar histologic information about the risk of ultrasound lesions (Table S6, http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX).

Inflammation of the chorionic plate and the chorion/decidua were associated with an increased risk of the diparetic form of CP (Table 4). Here, too, both vaginal and cesarean section sub-samples contributed to this increased risk.

Need organisms promote visible placenta inflammation to influence risks?

Fully 32% of inflamed placentas (155/488) did not harbor a microorganism, while 39% of non-inflamed placentas (298/758) harbored a microorganism. In the entire sample (Table 5) and in the vaginal-delivery sub-sample (Table S7, http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX), the risk of ventriculomegaly was higher when recovery of an organism was accompanied by histologic inflammation than when either characteristic occurred alone. In the Cesarean section sub-sample, the modestly increased risk of ventriculomegaly associated with recovery of an organism was not influenced by the presence of an inflammatory lesion in the placenta. No histologic placenta lesion predicted an echolucent lesion better when an organism was recovered than when it was not.

In the total sample (Table 6), as well as in the Cesarean section sub-sample (Table S8, http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX), the risk of diparetic CP was most prominently increased when recovery of an organism was unaccompanied by an inflammatory placenta lesion.

Table 6.

The odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) of ventriculomegaly and an echolucent lesion, as well as each cerebral palsy diagnosis, among children whose placenta had the characteristics listed on the left relative to the risk among children whose placenta harbored no recoverable organism and had no histologic lesion considered indicative of inflammation. Adjusted for gestational age (23–24, 25–26, 27 weeks).

| Organism | Placenta lesion* | Ultrasound lesion | Type of cerebral palsy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventriculomegaly | Echolucency | Quadriparesis | Diparesis | Hemiaresis | ||

| + | + | 2.5 (1.1, 5.7) | 1.7 (0.6, 4.8) | 1.5 (0.4, 5.5) | 0.8 (0.1, 4.7) | 3.5 (0.4, 34) |

| + | − | 1.2 (0.7, 1.9) | 1.5 (0.8, 2.6) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.1) | 4.0 (1.04, 16) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.8) |

| − | + | 0.6 (0.3, 1.2) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.7) | 0.9 (0.3, 27) | 2.8 (0.6, 14) | 0.6 (0.1, 3.0) |

| − | − | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Placenta lesions considered indicative of inflammation:

Inflammation of chorionic plate stage 3 and severity 3

Inflammation of chorion/decidua grades 3 and 4

Neutrophilic infiltration of fetal stem vessels

Umbilical cord vasculitis grades 3, 4 and 5

Discussion

Summary of key findings

We studied ultrasound lesions because they are the earliest readily evident indicators of brain damage in the preterm newborn. They are also less likely than later manifestations of brain damage, such as CP, to be influenced by postnatal exposures.

A number of our findings are entirely new. First, the recovery of relatively low virulence microorganisms from the placenta predicted both forms of cerebral white matter damage (ventriculomegaly and an echolucent lesion). Some of the organisms considered typical skin microflora in healthy individuals (e.g., Propionebacterium sp, Corynebacterium sp, non-aureus Staphylococcus sp.) were recovered even from placentas delivered by Cesarean section, which are the ones least likely to be `contaminated.' Second, the recovery of microorganisms from the placenta predicted quadriparetic and diparetic forms of CP. Third, polymicrobial infections appear to be biologically important in the pathogenesis of white matter damage and later CP. Fourth, membrane inflammation predicted both ventriculomegaly and diparetic CP. Fifth, the microorganisms did not have to elicit an inflammatory histologic response in the placenta to retain their association with diparetic CP. Sixth, the risk of ventriculomegaly was heightened by the combination of organism recovery and histologic inflammation.

Influence of route of delivery

We analyzed the microbiologic data in the entire sample and in the sub-samples defined by the route of delivery. This enabled us to explore whether phenomena associated with route of delivery modified the association between placenta colonization or infection and ultrasound abnormalities, as well as CP diagnoses. Such effect modification seems plausible for two reasons. First, bacteria recovered from placentas delivered vaginally might reflect contamination during the delivery process; such contamination is less likely with abdominal delivery (28). Second, the higher rate of bacterial colonization in placentas delivered vaginally might reflect the processes leading to vaginal delivery (e.g., preterm labor) (32), as well as the effects of repeated digital cervical examinations (33). Placentas delivered by Cesarean section are less likely to be affected by these processes, and therefore may be considered a “cleaner” sample.

In some situations, the vaginal delivery sub-sample and the Cesarean section sub-sample provided similar information. For example, the risk of ventriculomegaly associated with multi-species cultures in the vaginal delivery sub-sample [OR = 1.8 (0.9, 3.5)] was very similar to the risk in the Cesarean section sub-sample: [OR = 1.9 (1.02, 3.4)]. In other situations, the divergence is prominent. For example, the recovery of skin flora organisms was more prominently associated with an echolucent lesion in the Cesarean section sub-sample, while the association with diparetic CP was more prominent in the vaginal sub-sample.

Low virulence organisms

The non-pregnant uterus often harbors microorganisms (34). Their biologic significance remains unclear, but the mere presence of bacteria in the non-pregnant uterus raises the possibility that some of the tendency of the pregnant uterus to harbor microorganisms might not differ substantially from the propensity of the non-pregnant uterus to harbor microorganisms. On the other hand, the immunologic suppression that contributes to tolerance of the fetus might allow greater numbers of microorganisms in the gravid uterus than in the non-gravid uterus for long periods of time without clinical manifestations (35).

In contrast, we believe several observations suggest that some of the organisms in the pregnant uterus are biologically important. First, the proportion of placentas that harbored bacteria varies with the indication for preterm delivery. The recovery rate ranges from a low of 25% among Cesarean section-delivered placentas of women who had preeclampsia to 79% among placentas of women who had preterm labor at 23 weeks (28). Second, among placentas from pregnancies that ended with preterm labor, the prevalence of microorganisms decreases with increasing age (28) (36). Third, organisms are preferentially recovered from placentas that have high-grade chorionic plate inflammation and/or fetal vasculitis (neutrophilic infiltration of chorionic plate fetal stem vessels or umbilical cord vessels) (28). While some of these are high-virulence organisms, some are the low virulence organisms associated with ventriculomegaly, and diparesis. Others have detected bacterial DNA in human fetal membranes, even in the absence of histologic inflammation (37).

The multiplicity of relatively low-virulence microorganisms associated with white matter damage and CP suggests that the stimulus for the brain damage is not specific. Some low-virulence microorganisms are more likely to produce disease when in the presence of other low-virulence organisms than when alone (38). Thus, the polymicrobial cultures need not indicate contamination. Indeed, the co-occurrence of multiple low-virulence organisms might explain how they contribute to brain damage.

In our sample, Mycoplasma organisms were associated with an increased risk of diparetic CP but only in the Cesarean section sub-sample. This very limited association calls into question its biologic significance. Nevertheless, a previous study linked Mycoplasma in the placenta with an increased risk of white matter damage in low birth weight newborns (39), and a more recent report found that preterm infants whose amniotic fluid harbored Ureaplasma urealyticum were at increased risk for CP (40).

The distinctiveness of diparetic CP

CP occurs much more commonly in children born before 28 weeks than in those born at term (41). Some of the higher prevalence in children born months before term reflects the preferential occurrence of diparesis (42,43). Although the vulnerability of preterm-born children for diparetic CP might be due to the vulnerability of paraventricular white matter, the possibility that inflammatory phenomena associated with preterm delivery contribute to the occurrence of diparetic CP is supported by our finding that diparetic CP was predicted by recovery of a single microorganism, skin flora, and polymicrobial cultures, as well as by histologic inflammation of the placenta, even when an organism was not recovered.

We created an algorithm for diagnosing three clinically-distinguishable CP types (31). The observation that diparesis is the CP diagnosis most clearly associated with inflammatory phenomena supports our view that different forms of CP differ in some of their antecedents.

Our finding an association between histologic inflammation and diparetic CP is new. Thrombosis of fetal stem vessels predicted ventriculomegaly in this study, and predicted CP and other neurodisabilities in another study (44). In that study, “Chorionic plate thrombi were seen only with chorioamnionitis and accounted for the increased risk of neurologic impairment seen with chorioamnionitis.” We, too, have found that fetal stem vessel thrombosis occurs preferentially in inflamed placentas, but not exclusively (29).

Evolution of the inflammation hypothesis of cerebral white matter pathogenesis in the newborn

The hypothesis that bacteria can contribute to white matter damage and CP without entering the brain, first raised more than 30 years ago (5) has been supported and expanded by subsequent reports. First, cytokines are among the non-infectious circulating products of infection that appear to mediate white matter damage and CP (20). Second, the inflammation can begin before birth (11). Third, both innate and adaptive immune systems are probably also involved in white matter damage (45).

The two-hit hypothesis of cerebral white matter damage finds support from observations in immature animals that early exposures to inflammatory factors can increase the susceptibility of the brain to subsequent insults (sensitization) (46,47), and under slightly different circumstances reduce the susceptibility of the brain to subsequent insults (preconditioning) (48). Our finding that the risk of ventriculomegaly is heightened when the placenta not only harbors an organism, but is also histologically inflamed, might be an instance of sensitization.

The findings reported here support this view of inflammation-induced damage. The observation that placenta organisms convey risk information about brain damage in the offspring supports the hypothesis that some brain damage in the preterm newborn has its origins in utero. This observation also supports the hypothesis that some of the brain damage is initiated by bacteria, some of which can be typical skin microflora, or other low virulence microorganisms.

We previously suggested that the fetal inflammatory response to intrauterine infection might have two stages (11). Others have found support for this view (49). The initial stage, evident before histologic chorioamnionitis is identifiable, might be characterized by the synthesis of early cytokines by fetal endothelial cells. The second stage, accompanied by histologic inflammation of the placenta and umbilical cord, might be characterized by a stronger expression of later cytokines. Because we do not yet have information about circulating cytokines, we do not know when the first stage occurred in any of the children in our sample.

The risk of diparetic CP was increased in infants whose placenta was inflamed (Table 4), and in infants whose placenta harbored an organism without any accompanying placenta inflammation (Table 5). These observations raise the possibility that some of the placenta inflammation among children who developed diparesis was initiated by something other than a readily cultured and identified bacterium, such as a fastidious bacterium or a non-infectious stimulus (50).

The risk of ventriculomegaly was heightened by the joint occurrence of organism presence in the placenta and histologic inflammation of the placenta, The risk of diparetic CP, however, was increased in infants whose placenta was inflamed (Table 4), and in infants whose placenta harbored an organism, but without any further increase if the infant had both characteristics (Table 5). These observations raise the possibility that some of the placenta inflammation among children who developed diparesis was stimulated by something other than a bacterium.

In conclusion, extremely preterm infants whose placentas harbor low-virulence microorganisms appear to be at increased risk of cerebral white matter damage and CP. These findings are strong support for antenatal infectious contributions to perinatal white matter damage and its correlates. Our findings also suggest that histologic inflammation of the placenta is not an essential intermediary between microorganism presence and the development of diparetic CP, and that biologically significant inflammation of the placenta can occur in the absence of a recoverable microorganism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was supported by a cooperative agreement with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (5U01NS040069-05) and a program project grant form the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NIH-P30-HD-18655).

Abbreviations

- CP

cerebral palsy

- sp

species

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.pedresearch.org).

References

- 1.Msall ME. Developmental vulnerability and resilience in extremely preterm infants. JAMA. 2004;292:2399–2401. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marlow N, Wolke D, Bracewell MA, Samara M. Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hack M, Klein N. Young adult attainments of preterm infants. JAMA. 2006;295:695–696. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Shea TM, Counsell SJ, Bartels DB, Dammann O. Magnetic resonance and ultrasound brain imaging in preterm infants. Early Hum Dev. 2005;81:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leviton A, Gilles F, Neff R, Yaney P. Multivariate analysis of risk of perinatal telencephalic leucoencephalopathy. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;104:621–626. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inder TE, Wells SJ, Mogridge NB, Spencer C, Volpe JJ. Defining the nature of the cerebral abnormalities in the premature infant: a qualitative magnetic resonance imaging study. J Pediatr. 2003;143:171–179. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah DK, Doyle LW, Anderson PJ, Bear M, Daley AJ, Hunt RW, Inder TE. Adverse neurodevelopment in preterm infants with postnatal sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis is mediated by white matter abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging at term. J Pediatr. 2008;153:170–175. 175.e171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr B, Higgins RD. Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA. 2004;292:2357–2365. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glass HC, Bonifacio SL, Chau V, Glidden D, Poskitt K, Barkovich AJ, Ferriero DM, Miller SP. Recurrent postnatal infections are associated with progressive white matter injury in premature infants. Pediatrics. 2008;122:299–305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilles FH, Gomez IG. Developmental neuropathology of the second half of gestation. Early Hum Dev. 2005;81:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dammann O, Leviton A. Role of the fetus in perinatal infection and neonatal brain damage. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2000;12:99–104. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200004000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon BH, Kim CJ, Romero R, Jun JK, Park KH, Choi ST, Chi JG. Experimentally induced intrauterine infection causes fetal brain white matter lesions in rabbits. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:797–802. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Debillon T, Gras-Leguen C, Leroy S, Caillon J, Roze JC, Gressens P. Patterns of cerebral inflammatory response in a rabbit model of intrauterine infection-mediated brain lesion. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;145:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(03)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodts-Palenik S, Wyatt-Ashmead J, Pang Y, Thigpen B, Cai Z, Rhodes P, Martin JN, Granger J, Bennett WA. Maternal infection-induced white matter injury is reduced by treatment with interleukin-10. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1387–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan TM, Yu HM, Gu WZ, Li JP. White matter damage and chemokine induction in developing rat brain after intrauterine infection. J Perinat Med. 2005;33:415–422. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2005.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilles FH, Leviton A, Kerr CS. Endotoxin leucoencephalopathy in the telencephalon of the newborn kitten. J Neurol Sci. 1976;27:183–191. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(76)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell MJ, Hallenbeck JM. Effects of intrauterine inflammation on developing rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:570–579. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kannan S, Saadani-Makki F, Muzik O, Chakraborty P, Mangner TJ, Janisse J, Romero R, Chugani DC. Microglial activation in perinatal rabbit brain induced by intrauterine inflammation: detection with 11C-(R)-PK11195 and small-animal PET. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:946–954. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.038539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu YW. Systematic review of chorioamnionitis and cerebral palsy. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8:25–29. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dammann O, O'Shea TM. Cytokines and perinatal brain damage. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:643–663 v. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romero R, Espinoza J, Goncalves LF, Kusanovic JP, Friel L, Hassan S. The role of inflammation and infection in preterm birth. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:21–39. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murthy V, Kennea NL. Antenatal infection/inflammation and fetal tissue injury. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21:479–489. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagberg H, Mallard C, Jacobsson B. Role of cytokines in preterm labour and brain injury. BJOG. 2005;112:16–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards AD, Tan S. Perinatal infections, prematurity and brain injury. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:119–124. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000193290.02270.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redline RW, Minich N, Taylor HG, Hack M. Placental lesions as predictors of cerebral palsy and abnormal neurocognitive function at school age in extremely low birth weight infants (<1 Kg) Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10:282–292. doi: 10.2350/06-12-0203.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teele R, Share J. Ultrasonography of infants and children. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuban K, Adler I, Allred EN, Batton D, Bezinque S, Betz BW, Cavenagh E, Durfee S, Ecklund K, Feinstein K, Fordham LA, Hampf F, Junewick J, Lorenzo R, McCauley R, Miller C, Seibert J, Specter B, Wellman J, Westra S, Leviton A. Observer variability assessing US scans of the preterm brain: the ELGAN study. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:1201–1208. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0605-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onderdonk AB, Hecht JL, McElrath TF, Delaney ML, Allred EN, Leviton A, ELGAN Study Investigators Colonization of second-trimester placenta parenchyma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:52.e1–52.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hecht JL, Allred EN, Kliman HJ, Zambrano E, Doss BJ, Husain A, Pflueger SM, Chang CH, Livasy CA, Roberts D, Bhan I, Ross DW, Senagore PK, Leviton A, ELGAN Study Investigators Histological characteristics of singleton placentas delivered before the 28th week of gestation. Pathology. 2008;40:372–376. doi: 10.1080/00313020802035865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuban KC, O'Shea M, Allred E, Leviton A, Gilmore H, DuPlessis A, Krishnamoorthy K, Hahn C, Soul J, O'Connor SE, Miller K, Church PT, Keller C, Bream R, Adair R, Miller A, Romano E, Bassan H, Kerkering K, Engelke S, Marshall D, Milowic K, Wereszczak J, Hubbard C, Washburn L, Dillard R, Heller C, Burdo-Hartman W, Fagerman L, Sutton D, Karna P, Olomu N, Caldarelli L, Oca M, Lohr K, Scheiner A. Video and CD-ROM as a training tool for performing neurologic examinations of 1-year-old children in a multicenter epidemiologic study. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:829–831. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200101001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuban KC, Allred EN, O'Shea M, Paneth N, Pagano M, Leviton A, ELGAN Study Cerebral Palsy-Algorithm Group An algorithm for identifying and classifying cerebral palsy in young children J. Pediat. 2008;153:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexander JM, Mercer BM, Miodovnik M, Thurnau GR, Goldenberg RL, Das AF, Meis PJ, Moawad AH, Iams JD, Vandorsten JP, Paul RH, Dombrowski MP, Roberts JM, McNellis D. The impact of digital cervical examination on expectantly managed preterm rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1003–1007. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Cliver SP, Conner M, Goepfert AR. Endometrial microbial colonization and plasma cell endometritis after spontaneous or indicated preterm versus term delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Redline RW, Lu CY. Role of local immunosuppression in murine fetoplacental listeriosis. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1234–1241. doi: 10.1172/JCI112942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DiGiulio DB, Romero R, Amogan HP, Kusanovic JP, Bik EM, Gotsch F, Kim CJ, Erez O, Edwin S, Relman DA. Microbial Prevalence, Diversity and Abundance in Amniotic Fluid During Preterm Labor: A Molecular and Culture-Based Investigation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steel JH, Malatos S, Kennea N, Edwards AD, Miles L, Duggan P, Reynolds PR, Feldman RG, Sullivan MH. Bacteria and inflammatory cells in fetal membranes do not always cause preterm labor. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:404–411. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000153869.96337.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brogden KA, Guthmiller JM, Taylor CE. Human polymicrobial infections. Lancet. 2005;365:253–255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17745-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dammann O, Allred EN, Genest DR, Kundsin RB, Leviton A. Antenatal mycoplasma infection, the fetal inflammatory response and cerebral white matter damage in very-low- birthweight infants. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2003;17:49–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2003.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berger A, Witt A, Haiden N, Kaider A, Klebermasz K, Fuiko R, Langgartner M, Pollak A. Intrauterine infection with Ureaplasma species is associated with adverse neuromotor outcome at 1 and 2 years adjusted age in preterm infants. J Perinat Med. 2009;37:72–78. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hagberg B, Hagberg G, Olow I, von Wendt L. The changing panorama of cerebral palsy in Sweden. VII. Prevalence and origin in the birth year period 1987–90. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:954–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vohr BR, Msall ME, Wilson D, Wright LL, McDonald S, Poole WK. Spectrum of gross motor function in extremely low birth weight children with cerebral palsy at 18 months of age. Pediatrics. 2005;116:123–129. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robertson CM, Watt MJ, Yasui Y. Changes in the prevalence of cerebral palsy for children born very prematurely within a population-based program over 30 years. JAMA. 2007;297:2733–2740. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Redline RW, Wilson-Costello D, Borawski E, Fanaroff AA, Hack M. Placental lesions associated with neurologic impairment and cerebral palsy in very low-birth-weight infants. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:1091–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leviton A, Dammann O, Durum SK. The adaptive immune response in neonatal cerebral white matter damage. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:821–828. doi: 10.1002/ana.20662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dommergues MA, Patkai J, Renauld JC, Evrard P, Gressens P. Proinflammatory cytokines and interleukin-9 exacerbate excitotoxic lesions of the newborn murine neopallium. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eklind S, Mallard C, Arvidsson P, Hagberg H. Lipopolysaccharide induces both a primary and a secondary phase of sensitization in the developing rat brain. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:112–116. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000163513.03619.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mallard C, Hagberg H. Inflammation-induced preconditioning in the immature brain. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;12:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romero R, Espinoza J, Goncalves LF, Kusanovic JP, Friel LA, Nien JK. Inflammation in preterm and term labour and delivery. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Virgilio F, Ceruti S, Bramanti P, Abbracchio MP. Purinergic signalling in inflammation of the central nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.