Summary

The predictiveness curve shows the population distribution of risk endowed by a marker or risk prediction model. It provides a means for assessing the model’s capacity for stratifying the population according to risk. Methods for making inference about the predictiveness curve have been developed using cross-sectional or cohort data. Here we consider inference based on case-control studies which are far more common in practice. We investigate the relationship between the ROC curve and the predictiveness curve. Insights about their relationship provide alternative ROC interpretations for the predictiveness curve and for a previously proposed summary index of it. Next the relationship motivates ROC based methods for estimating the predictiveness curve. An important advantage of these methods over previously proposed methods is that they are rank invariant. In addition they provide a way of combining information across populations that have similar ROC curves but varying prevalence of the outcome. We apply the methods to PSA, a marker for predicting risk of prostate cancer.

Keywords: biomarker, classification, predictiveness curve, risk prediction, ROC curve, total gain

1. Background

The importance of biomarkers in disease screening, diagnosis, and risk prediction has been generally recognized. A well-established criterion for biomarker selection is classification accuracy, commonly characterized by the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and its summary measures. However, classification is not always the major focus. Oftentimes we use biomarkers to calculate the risk of an outcome. Recently, there has been increasing awareness that the ROC curve is not the most relevant tool for assessing a biomarker whose purpose is risk prediction (Gail and Pfeiffer, 2005; Cook, 2007; Huang et al., 2007; Pepe et al., 2008a; Pencina et al., 2008). On the one hand, the ROC curve does not display risk which is of primary interest to patients and clinicians. On the other hand, criteria relating to classification oftentimes can be too stringent for evaluation of a risk prediction marker. To characterize the predictive capacity of a continuous marker or risk model, a new graphical tool, the predictiveness curve, has been proposed to display the population distribution of disease risk predicted by the particular marker or risk model (Bura and Gastwirth, 2001; Huang et al., 2007; Pepe et al., 2008a).

Let D denote a binary outcome that we term disease here, D = 1 for diseased and D = 0 for non-diseased. Let Y denote a marker of interest and define Risk(Y) = P (D = 1|Y), the risk calculated on the basis of Y. We use the term “risk” in a broad sense, to include presence of disease at the time Y is measured, and to include future onset of disease after Y is measured, depending on the application. Assuming Risk(Y) is monotone increasing in Y, the predictiveness curve for Y is the curve R(v) vs v for v ∈ (0, 1), where R(v) is the risk corresponding to the vth percentile of Y. The inverse function R−1(p) = P (Risk(Y) ≤ p) is the proportion of the population with risks less than or equal to p. In other words R−1(p) is the population cumulative distribution function of risk. An appealing property of the predictiveness curve is that it provides a common meaningful scale for making comparisons between markers or risk models that may not be comparable on their original scales. Comparisons might be based on R(v), the risk percentiles. A better risk prediction marker tends to have larger variability in percentiles. A clinically compelling comparison is based on R−1(p). Suppose there exists a low risk threshold pL and/or a high risk threshold pH which are agreed upon apriori such that the decision for treatment is recommendation for or against if the estimated risk for a patient is above pH or below pL. A marker or risk model is preferable to another if it categorizes more people into the low and high risk ranges where treatment decisions are easy to make and leaves fewer subjects in the equivocal risk range. That is, we hope to identify markers that have large values of R−1(pL) and 1 − R−1(pH) and small values of R−1(pH) − R−1(pL).

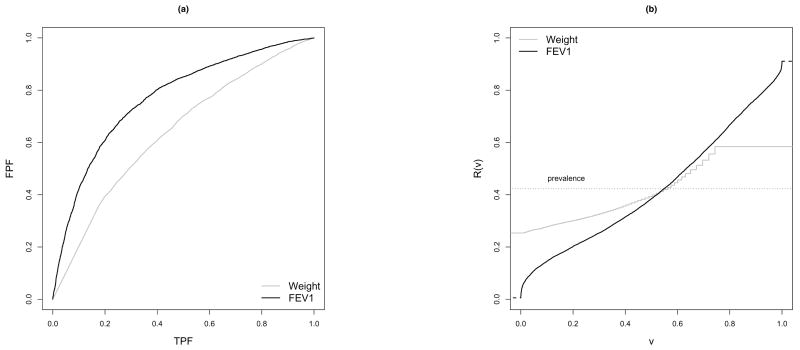

An example of biomarker evaluation is included in Figure 1, where the ROC and predictiveness curves for weight and FEV1 are displayed as classification or risk prediction markers for pulmonary exacerbation in children with cystic fibrosis. The empirical ROC curves shown in Figure 1(a) suggest that FEV1 has better classification accuracy than weight. The corresponding predictiveness curves estimated in Huang et al. (2007) are shown in Figure 1(b). We see for example that at the 90th percentile the risk is 0.76 for FEV1 but only 0.58 for weight suggesting FEV1 is a better marker of high risk than weight. FEV1 is also a better marker of low risk. The 10th percentile of risk is 0.28 according to weight but much lower based on FEV1, 0.15. We can also consider the inverse function taking pH = 0.75 and pL = 0.25. FEV1 is predictive of low risk in R−1(0.25) = 29% of the population, whereas none are identified as low risk with weight. FEV1 also identifies more people at high risk than does weight with 1 − R−1(0.75) = 12% and 0% respectively. Less patients are categorized into the equivocal risk range according to FEV1 (59%) than according to weight (100%).

Figure 1.

ROC curves and Predictiveness curves for two markers of pulmonary exacerbation in children with cystic fibrosis.

Semi-parametric estimators for making inference about the curve and for making pointwise comparisons between two curves from a cohort study have been developed by Huang et al. (2007). Since case-control studies are often performed in the early phases of biomarker development (Pepe et al., 2001), it is important to estimate the predictiveness of continuous biomarkers in studies that use this type of design as well. When the disease of interest is rare in the population, using a case-control design to oversample cases can be more efficient than simple random sampling from the population. In this paper, we consider estimation of the predictiveness curve from a case-control study, assuming the disease prevalence is known apriori or that it can be estimated either from an independent cohort or from a parent cohort study within which the case-control marker study is nested (Baker et al., 2002; Pepe et al., 2008b). The methodology is based on modeling a parametric ROC curve and exploits the one-to-one relationship between the predictiveness curve and the ROC curve.

2. Relationship between the Predictiveness Curve and the ROC Curve

Here we focus on the scenario of a single continuous marker. Note the marker may be a predefined combination of predictors. For example the Framingham risk score is a combination of age, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, treatment for hypertension, and cigarette smoking. Denote Y, YD, and YD̄ as the marker measurement in the general, diseased, and non-diseased populations respectively. Let F, FD, and FD̄ be the corresponding distribution functions and let f, fD, and fD̄ be the density functions. Let ρ = P (D = 1) be the disease prevalence. We consider a case-control sample with nD cases and nD̄ controls.

Throughout this manuscript, we assume the risk of disease P (D = 1|Y) is monotone increasing in Y. Under this monotone increasing risk assumption, we have that the vth risk percentile is R(v) = P {D = 1|Y = F−1(v)}. The following theorem characterizes the one-to-one relationship between the predictiveness curve and the ROC curve.

Theorem 1

Suppose YD and YD̄ have absolutely continuous distribution functions and P (D = 1|Y) is monotone increasing in Y. Further suppose the support of YD̄ covers the support of YD. Then R(v) vs v can be represented as

| (1) |

where the ROC curve at false positive rate t is ROC(t), and ROC′(t) is its derivative with respect to t.

Proof

For v ∈ (0, 1), let y = F−1(v). Suppose FD̄ (y) = 1 − t. Since y is within the support of YD̄, we have trivially. Let ℒR denote the likelihood ratio function: ℒR(y) = fD(y)/fD̄ (y). We have

Moreover,

The last equality holds since (Green and Swets, 1966). Note the result can be generalized to the scenario when the upper bound of the support for YD is larger than the upper bound of the support for YD̄. We omit the details because it is not relevant for the method discussed in this paper.

Theorem 1 shows that the predictiveness curve can be constructed from the ROC curve given the disease prevalence. Conversely, the ROC curve can also be constructed from the predictiveness curve. Specifically, as pointed out in Pepe et al. (2008a), corresponding to a percentile value v, the false positive fraction (FPF) is , and the true positive fraction (TPF) is .

The one-to-one relationship between the ROC curve and the predictiveness curve suggests that there may be a simple relationship between standard summary measures for the curves. One interesting summary measure of the predictiveness curve previously proposed by Bura and Gastwirth (2001) is the total gain (TG), , the area sandwiched between the predictiveness curve and the horizontal line at ρ, the prevalence. The latter is the predictiveness curve for a completely uninformative marker. Since a better risk prediction marker has steeper predictiveness curve, Bura and Gastwirth (2001) argued for gauging predictiveness with the size of TG: better markers have larger values. In Theorem 2, we show that TG is equivalent to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov measure of distance between two distributions (case vs control), a traditional ROC summary statistic (Pepe, 2003, pg. 80). Proof of Theorem 2 is given in the Appendix.

Theorem 2

Under the assumption that P (D = 1|Y) is monotone increasing in Y, we have TG = 2ρ(1 − ρ) supt{ROC(t) − t} = 2ρ(1 − ρ) maxc{sensitivity(c) + specificity(c) − 1}, where sensitivity(c) and specificity(c) denote the values when threshold c is used for positive classification with the marker.

Youden’s index (Youden, 1950), which has a long history as a summary performance measure for binary tests is the sum of sensitivity and specificity minus 1, and is appealing when the costs associated with false positive and false negative errors are equal. The point on the ROC curve that maximizes Youden’s index is often called the ‘optimal point’. It is interesting to see that the TG is related to this optimal point on the ROC curve. Refer to Fluss et al. (2005) for various methods to estimate Youden’s index.

Theorem 1 also has implications for estimating the predictiveness curve from a case-control sample. We can estimate a smooth ROC curve first and then derive the corresponding predictiveness curve based on (1), where we plug in a known or estimated value for disease prevalence. This is an appealing procedure for the following reasons: (i) When researchers are interested in evaluating a biomarker from multiple angles, they may choose to display both the ROC curve and the predictiveness curve. It is important in this situation that the assumptions behind estimates of the two curves are compatible with each other. Deriving the predictiveness curve from the ROC curve will guarantee this; (ii) The fact that the ROC curve can be estimated only from ranked data implies that methods for deriving the predictiveness curve from a rank-based ROC curve estimate also only depend on ranks. This contrasts with previous methods proposed (Huang et al., 2007); (iii) Estimation of the ROC curve is a well studied problem. There are a wide variety of methods available; (iv) It is natural to estimate the ROC curve from a case-control study since sensitivity and specificity are defined conditional on disease status, so case-control data are accommodated by these methods in contrast to our previous approach (Huang et al., 2007); (v) A fundamental property of the predictiveness curve is that the area under the curve is equal to ρ since . The area under an estimated predictiveness curve R̂(v) vs v, on the other hand, is not necessarily equal to the prevalence estimate. It depends on the procedure employed for estimation. However, if a predictiveness curve is calculated using a prevalence estimate ρ̂ and an estimated ROC curve which is differentiable almost everywhere, then the area under the estimated predictiveness curve is always equal to ρ̂. In particular

This is a desirable property for a predictiveness curve estimate. When we compare two markers with respect to the steepness of their estimated predictiveness curves, it facilitates visual comparisons when the estimated curves have the same area under the curve; (vi) Finally, a unique property of the ROC curve based method compared to alternative methods is its ability to borrow information across populations when a marker’s discriminatory performance (ROC curve) is the same across different populations. When this happens, a common ROC curve can be estimated using samples from different populations (Janes and Pepe, 2008a,b,c; Huang et al., 2008). The estimator can be combined with disease prevalences to estimate predictiveness curves for individual populations. In contrast, one cannot take advantage of the constant ROC curve assumption in other frameworks, for example, when risk models and marker distributions are estimated separately (Huang et al., 2007).

Before we start exploring a specific ROC based method for estimation, we note that the assumption that P (D = 1|Y = y) is increasing in y implies that ℒR(y) is increasing in y which in turn implies that ROC′(t) is decreasing in t. That is, a monotone increasing risk function assumption implies concavity of the corresponding ROC curve. Therefore, we prefer methods that lead to concave estimates of the ROC curve. Note that concavity is always a desirable property for an ROC curve because it guarantees that the ROC curve will never cross the 45° “guessing line” (Dorfman et al., 1996) and because it is a property of the optimal ROC curve for decision rules based on Y (Egan, 1975).

3. Estimation Using Parametric ROC Models

Approaches to estimating an ROC curve vary along a spectrum regarding assumptions made. At one extreme, we can model the marker distributions within cases and controls parametrically and calculate the corresponding ROC curve. For example Wieand et al. (1989) modeled YD and YD̄ as normally distributed. A method with more flexibility is to assume YD and YD̄ are normally distributed after a BoxCox transformation (Zou and Hall, 2000; Faraggi and Reiser, 2002). At the other extreme, an ROC curve can be estimated completely nonparametrically using empirical estimators for FD and FD̄ (Greenhouse and Mantel, 1950; Hsieh and Turnbull, 1996; Wieand et al., 1989). A method in-between is to assume a parametric model for the ROC curve without enforcing any parametric distributional assumptions on marker measures. This semi-parametric approach is more efficient than the nonparametric approach, yet more robust than modeling the marker distributions parametrically. There are many existing semi-parametric approaches we can use to estimate a parametric ROC curve. Metz et al. (1998) proposed grouping continuous data and estimating the parameters based on the Dorfman and Alf maximum-likelihood algorithm for ordinal data (Dorfman and Alf, 1969). Hsieh and Turnbull (1996) developed a generalized least squares method to fit a parametric ROC curve to discretized continuous data. Pepe (2000) and Alonzo and Pepe (2002) proposed a distribution-free ROC-GLM procedure. Zou and Hall (2000) developed an estimator maximizing the likelihood function of the order statistics. Pepe and Cai (2004) maximized the pseudolikelihood based on standardized marker values. Cai and Moskowitz (2004) developed a maximum profile likelihood approach which provides fully efficient parameter estimates. These semi-parametric approaches have the attractive property of being rank-based. We will focus on these semi-parametric approaches for estimation. First, consider how to formulate a parametric ROC model.

3.1 Modeling the Predictiveness Curve over the Whole Range

The most widely used parametric ROC model is the binormal ROC curve. It assumes that there exists a common unspecified monotone transformation h, which transforms the marker distributions in both cases and controls to normality. Suppose , the corresponding ROC curve is ROC(t) = Φ{a+bΦ−1(t)}, where a = (μD − μD̄)/σD and b = σD̄/σD.

Many algorithms including the semi-parametric methods listed above have been proposed to fit the binormal ROC curve. Moreover, the binormal assumption is thought to fit many real datasets (Hanley, 1988). However, a problem with using the binormal ROC model is that it is not concave in (0, 1) unless b = 1 (i.e. the normal distributions for cases and controls have the same variance). This can be seen from the log of the derivative of ROC(t) which is quadratic in Φ−1(t)

| (2) |

where C+ is some positive constant.

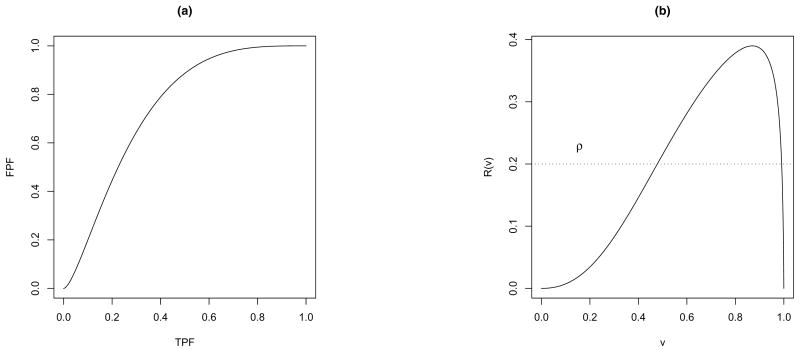

The lack of concavity for a binormal model has been shown to have only a minor impact on estimation of the ROC curve itself. However, it can have a large impact on the derivative of the ROC curve, which in turn can cause problems in estimating the predictiveness curve. To get a flavor for this, look at the example in Figure 2, where 50 cases and 50 controls are simulated from normal distributions with equal variances. The estimated binormal ROC curve (Figure 2a) has a tiny squiggle in the left-hand tail which is almost unnoticeable, whereas the corresponding predictiveness curve estimate has a big non-monotone tail at the right end (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Examples of (a) non-concave binormal ROC curve and (b) the corresponding predictiveness curve.

To avoid this problem, one solution is to employ other parametric models that yield concave ROC curves. Two parametric models for concave ROC curves are the bigamma and bilomax models. The bigamma ROC curve (Dorfman et al., 1996) assumes there exists a common monotone transformation that transforms the distributions of YD and YD̄ into gamma distributions with the same shape parameter. The use of this ROC model is hindered by the fact that the ROC function cannot be written in closed-form. The bilomax ROC curve proposed by Campbell and Ratnaparkhi (1993) assumes the existence of a monotone transformation h such that the distributions of h(YD̄) and h(YD) are lomax or type II Pareto (Lomax, 1954). A detailed account of methods that employ the bilomax ROC curve can be found in Huang (2007).

In the rest of this paper, we focus on an alternative strategy. Since the binormal ROC curve is widely used, we develop techniques for predictiveness curve estimation based on this model. However, instead of fitting the predictiveness curve and the ROC curve over the entire domain (0,1), we only model a portion of it that is of interest. In this approach we can ensure concavity of the ROC curve and consequently monotonicity of the predictiveness curve within a restricted range of interest.

3.2 Modeling a Portion of the Predictiveness Curve

In addition to addressing the concavity issue, there are several other reasons to consider estimating the predictiveness curve over a subinterval of (0,1). First, by enforcing model assumptions on only a portion of the curve, we increase robustness of the estimate. Second, risks only within a particular range may be of primary interest. Third, a parametric ROC model creates lack of flexibility in the estimated predictiveness curve at the boundary. As shown in Table 1, when a binormal ROC model is enforced over the whole (0,1) domain, the boundary of the predictiveness curve has value either 0 or 1. However, in applications the risk function is often not 0 or 1 at extreme values of the marker. Therefore, the binormal predictiveness curve will not fit at the boundary in these settings.

Table 1.

Properties of binormal ROC model and the corresponding predictiveness curve.

| lim ROC′(t) | Implications for lim R(v) |

|---|---|

| Binormal ROC(t) = Φ {a + bΦ−1(t)} | |

| b < 1 | |

| limt→1 ROC′ (t) = ∞ | limv→0 R(v) = 1 |

| limt→0 ROC′ (t) = ∞ | limv→1 R(v) = 1 |

| b > 1 | |

| limt→1 ROC′ (t) = 0 | limv→0 R(v) = 0 |

| limt→0 ROC′ (t) = 0 | limv→1 R(v) = 0 |

| b = 1 | |

| limt→1 ROC′ (t) = 0 | limv→0 R(v) = 0 |

| limt→0 ROC′ (t) = ∞ | limv→1 R(v) = 1 |

Researchers in the field of diagnostic test evaluation have long been interested in the partial ROC curve. For example, in screening studies, it is important to minimize the unnecessary cost due to false positive test results, hence the region of the ROC curve corresponding to low FPF is most relevant. If the purpose of the study is disease diagnosis, it is critical not to miss detecting subjects with disease, and hence the part of the ROC curve corresponding to high TPF is of primary interest. Modeling a partial ROC curve and the area under it has been proposed and studied (McClish, 1989; Thompson and Zucchini, 1989; Jiang et al., 1996; Dodd and Pepe, 2003; Pepe and Cai, 2004).

Interestingly, when concavity is required only over a certain portion of the ROC curve, parametric ROC models which are not concave in the whole range may be employed. Consider the classic binormal ROC curve, ROC(t) = Φ {a + bΦ−1(t)}, whose derivative is shown in (2). Consider the following two scenarios: (i) If 0 < b < 1, ROC′ (t) increases as {Φ−1(t) + ab/(b2 − 1)}2 increases. Thus for ROC′(t) to be monotone decreasing, we need to have Φ−1(t) < −ab/(b2 − 1) ⇔ t < Φ (−ab/(b2 − 1)) ⇔ a > (1 − b2) Φ−1(t)/b. That is, by imposing this restriction on (a,b) over the FPF range of interest, the corresponding portion of the ROC curve is guaranteed to be concave. (ii) If b > 1, ROC′(t) increases as {Φ−1(t) + ab/(b2 − 1)}2 decreases. Thus for ROC′(t) to be monotone decreasing, we need to have Φ−1(t) > −ab/(b2 − 1) ⇔ t > Φ (−ab/(b2 − 1)) ⇔ a > (1 − b2) Φ−1(t)/b. We can impose these restrictions during estimation to guarantee concavity of the partial binormal ROC curve over the range of interest. Suppose concavity is required for t ∈ (t0, t1), we fit the ROC model with the restriction on parameter estimates (a, b): a > (1−b2) Φ−1(t0)/b and a > (1 − b2) Φ−1(t1)/b.

3.3 Estimation

Denote by ROCθ(t), t ∈ (0, 1), the parametric ROC curve with parameter θ. Define and H(θ, t, ρ) = 1−(1− ρ)t− ρROCθ(t). Let G−1(θ, p, ρ) = inf {t : G(θ, t, ρ) ≤ p and } and H−1(θ, v, ρ) = inf {t : H(θ, t, ρ) ≤ v}. We can estimate θ using algorithms described before and denote its estimator by θ̂. Let ρ̂ be the estimate of disease prevalence available to us. Estimators of the corresponding predictiveness curve and its inverse are

In practice, oftentimes there does not exist a closed-form for H−1(·) or G−1(·) and numerical methods need to be implemented to calculate R̂(v) and R̂−1(p).

The prevalence estimate may not have sampling variability in some applications. For example, if ρ derives from a population disease registry such as SEER(http://seer.cancer.gov), its value is essentially known due to the large sample size involved. Moreover, in some settings investigators will want to substitute fixed values of ρ into the predictiveness estimate in order to determine prevalences that render the marker useful as indicated by the corresponding predictiveness curves. This sort of “what-if” exercise, could lead to consideration of specific populations for application of the marker. In other applications the prevalence will be estimated with sampling variability from data. Such data may be independent of the case-control data, for example when it is based on a report from the literature. Alternatively it may be derived from a cohort within which the case-control study is nested. The nested case-control design has been proposed as the preferred design for pivotal evaluation of biomarkers for classification (Pepe et al., 2001, 2008b; Baker et al., 2002) and involves measuring the outcome D for all subjects in random sample from the population of interest but the marker Y only for a subsample of cases and for a subsample of controls.

3.4 Asymptotic Theory

Suppose R̂ (v) and R̂ −1(p) are estimators of R(v) and R−1(p). We assume the following conditions hold.

Assumptions

, where n = nD + nD̄. Note that for the special case where ρ is assumed known, we have Σθρ = Σρρ = 0.

ROCθ(t) is differentiable with respect to θ and t.

G(θ, t, ρ) is differentiable with respect to θ, t, and ρ with derivatives g1, g2, and g3.

H−1(θ, v, ρ) is differentiable with respect to θ.

G−1(θ, p, ρ) is differentiable with respect to θ.

Theorem 3

We have

where , with , and

Theorem 4

We have

where , with

and .

Observe that the variance of R̂(v) and R̂−1(p) are related by the equation σ2(v) = {∂R(v)/∂v}2 τ2(p) = [g2 {θ, H−1(θ, v)} ∂H−1(θ, v)/∂v]2 τ2(p) where p = R(v). Theorems 3 and 4 follow directly from the continuous mapping theorem and the chain rule. Typically the terms in Theorem 3 and in Theorem 4 are zero because Σθρ= 0, even in a nested case-control study. This follows because θ is estimated from the conditional distribution of the marker given disease status, while ρ̂ is a function only of disease status data.

Due to the lack of closed-forms for H−1(·) and G−1(·), numerical differentiation methods are needed for calculation of their derivatives when estimating the asymptotic variances of R̂ (v) and R̂−1(p). We use bootstrap resampling instead for variance estimation with resampling reflecting the study design. Separate resampling of cases and controls is employed, with resampling of D for the entire cohort when prevalence is estimated.

4. Simulation

We simulate a nested case-control study to evaluate the finite sample performance of predictiveness curve estimates. To generate data we use disease prevalence ρ = 0.2, and the binormal model for the risk marker Y : h(Y)|D = 0 ~ N(0, 1) and h(Y)|D = 1 ~ N(μ, 1), where h(y) = log{exp(y) −3.5}. A cohort of size n = 5,000 comprises the parent study, with D generated as Bernoulli with probability ρ = 0.2. The risk marker is then generated for equal numbers of cases and controls nested within the cohort. Suppose a low risk threshold 0.1 and a high risk threshold 0.3 are of major interest. The measures studied in the simulation are R(v) and R−1(p) for p = 0.1, 0.3 and the corresponding R(v) for v = R−1(p). The effect of the FPF range chosen for fitting the partial ROC curve is evaluated as follows: (i) a binormal ROC curve with t ∈ (0.01, 0.99) is fitted for estimating both p = R−1(0.1) and p = R−1(0.3) and corresponding R(v) for v = R−1(p); (ii) a binormal ROC curve with t ∈ (0.5, 0.99) is fitted for estimating R−1(0.1) and the corresponding R(v), while t ∈ (0.01, 0.50) is employed when estimating R−1(0.3) and the corresponding R(v). The pseudolikelihood procedure (Pepe and Cai, 2004) is used for fitting the ROC model.

For comparison purposes, we note that an alternative approach for estimation of the predictiveness curve is to separately estimate the risk model and the marker distribution. The method proposed for cohort studies by Huang et al. (2007) can be naturally extended to case-control studies. Assume the population risk model is logitP (D = 1|Y) = β0 + β1Y. Let Sampled indicate being sampled in the case-control study. According to Bayes’ theorem

Therefore to estimate the risk model, we apply an ordinary linear logistic regression model to the data and correct the intercept using the term −logit (ρ̂) + log (nD/nD̄). The marker distribution is estimated as a weighted average of the empirical marker distributions within cases (F̃D) and controls (F̃D̄) (Huang, 2007), i.e. F̃(y) = ρ̂F̃D(y) + (1 − ρ̂)F̃D̄(y).

We evaluate three models with μ = 0.5, 0.8, 1.2, which correspond to markers with relatively weak, moderate, and strong predictive capacity. For each model, we study performance of the predictiveness estimators for case-control sample sizes varying from 500 to 1000. For each sample size, 1000 Monte-Carlo simulations are performed. The bootstrap is conducted for variance estimation, resampling marker data within cases and controls separately. Also resampled is disease status for the parent cohort in order to incorporate variability in ρ̂. For each simulation, 250 bootstrap samples are generated. The 95% confidence intervals are constructed from the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of the bootstrap distributions.

Results for bias, mean squared error (MSE), and empirical coverage probability of confidence intervals are shown in Table 2. We see that the rank-invariant estimators based on estimating the partial ROC curve have good performance. Bias is minimal for R(v) and for R−1(p). All 95% bootstrap confidence intervals have reliable coverage. On the other hand, the estimator based on logistic regression is biased since this method is not rank-invariant and in this example an incorrect scale for the marker is employed in the risk model. It has larger MSE than the partial ROC curve based estimator and very poor coverage in this simulation setting.

Table 2.

Performance of the predictiveness curve estimators, where MSE is mean squared error and ECP is empirical coverage of bootstrap confidence interval.

| nD = nD̄ = 250 | nD = nD̄ = 500 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R(v1) | R−1(0.1) | R(v2) | R−1(0.3) | R(v1) | R−1(0.1) | R(v2) | R−1(0.3) | ||

| Model 1: μ = 0.5, v1 = R−1 (0.1) = 0.074, v2 = R−1(0.3) = 0.886 | |||||||||

| Bias | |||||||||

| PROC1 | −0.001 | 0.001 | −4.6e-5 | 6.4e-4 | −1.4e-4 | −9.8e-4 | −7.0e-4 | 0.0015 | |

| PROC2 | −8.8e-4 | 0.016 | −9.8e-4 | 3.9e-4 | −1.2e-4 | 0.0068 | −0.0012 | 0.0033 | |

| LREG* | 0.011 | −0.11 | −0.023 | 0.05 | 0.012 | −0.13 | −0.024 | 0.050 | |

| MSE | |||||||||

| PROC1 | 1.8e-4 | 0.0048 | 2.2e-4 | 0.002 | 9.1e-4 | 0.0023 | 1.4e-4 | 0.0012 | |

| PROC2 | 2.8e-4 | 0.0093 | 2.4e-4 | 0.0032 | 1.4e-4 | 0.0037 | 1.4e-4 | 0.0018 | |

| LREG* | 2.7e-4 | 0.022 | 6.7e-4 | 0.0032 | 2.2e-4 | 0.022 | 6.7e-4 | 0.0030 | |

| ECP | |||||||||

| PROC1 | 95.4 | 97.1 | 97.2 | 98.4 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 98.6 | 98.8 | |

| PROC2 | 96.2 | 97.8 | 97.6 | 99.8 | 96.3 | 97.4 | 98.4 | 99.3 | |

| LREG* | 85.1 | 85.0 | 47.5 | 47.2 | 75.3 | 75.2 | 19.3 | 19.4 | |

| Model 2: μ = 0.8, v1 = R−1 (0.1) = 0.232, v2 = R−1(0.3) = 0.808 | |||||||||

| Bias | |||||||||

| PROC1 | −7e-4 | −8.9e-4 | −2e-4 | −4.4e-4 | −3.7e-4 | 5.6e-5 | 4.1e-4 | −8.5e-4 | |

| PROC2 | −7.7e-4 | 0.0091 | −7e-4 | −0.002 | −4.8e-5 | 0.0031 | −1.2e-4 | −0.0011 | |

| LREG* | 0.017 | −0.14 | −0.035 | 0.041 | 0.017 | −0.15 | −0.035 | 0.041 | |

| MSE | |||||||||

| PROC1 | 1.7e-4 | 0.003 | 2.9e-4 | 7.3e-4 | 7.9e-5 | 0.0014 | 1.6e-4 | 4.1e-4 | |

| PROC2 | 2.2e-4 | 0.0047 | 3.0e-4 | 0.0015 | 1.1e-4 | 0.0020 | 1.8e-4 | 6.3e-4 | |

| LREG* | 4.1e-4 | 0.024 | 0.0014 | 0.0020 | 3.5e-4 | 0.026 | 0.0013 | 0.0019 | |

| ECP | |||||||||

| PROC1 | 93.5 | 93.6 | 97.1 | 97.1 | 95.8 | 95.8 | 98.6 | 98.6 | |

| PROC2 | 94.3 | 94.8 | 97.2 | 98.4 | 95.6 | 95.9 | 98.4 | 99.0 | |

| LREG* | 65.6 | 65.8 | 29.0 | 29.0 | 41.6 | 41.8 | 7.3 | 7.4 | |

| Model 3: μ = 1.2, v1 = R−1 (0.1) = 0.396, v2 = R−1(0.3) = 0.770 | |||||||||

| Bias | |||||||||

| PROC1 | 3.2e-4 | −0.0043 | −7.6e-4 | −6.2e-5 | −1e-4 | −5e-4 | 1.3e-4 | −5.7e-4 | |

| PROC2 | −6.4e-4 | 0.008 | 0.0014 | 0.006 | 9.7e-5 | 0.0019 | −4.9e-4 | −0.0019 | |

| LREG* | 0.021 | −0.17 | −0.044 | 0.03 | 0.021 | −0.18 | −0.044 | 0.03 | |

| MSE | |||||||||

| PROC1 | 1.2e-4 | 0.0029 | 4.2e-4 | 3.4e-4 | 5.7e-5 | 0.0012 | 2.9e-4 | 2.4e-4 | |

| PROC2 | 1.4e-4 | 0.0037 | 5.8e-4 | 8.7e-4 | 6.3e-5 | 0.0014 | 3.7e-4 | 4e-4 | |

| LREG* | 5.2e-4 | 0.032 | 0.0022 | 0.0011 | 4.7e-4 | 0.034 | 0.0022 | 0.001 | |

| ECP | |||||||||

| PROC1 | 94.2 | 94.2 | 96.9 | 96.9 | 95.7 | 95.7 | 98.7 | 98.7 | |

| PROC2 | 92.7 | 92.9 | 97.3 | 99.2 | 95.5 | 95.6 | 97.7 | 99.1 | |

| LREG* | 31.9 | 31.9 | 36.8 | 36.6 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 11.2 | 10.7 | |

partial binormal ROC modeling with t ∈ (0.01, 0.99)

partial binormal ROC modeling with t ∈ (0.50, 0.99) for estimating R−1(0.1) and R(v1) for v1 = R−1(0.1), and t ∈ (0.01, 0.50) for estimating R−1(0.3) and R(v2) for v2 = R−1(0.3)

logistic regression based method

Finally, Table 3 presents average width of percentile bootstrap confidence intervals based on partial binormal ROC curve fitting, as a function of FPF range, predictive strength of the marker and sample size. Observe that in general estimation of R−1(p) is more challenging than estimation of R(v): the former has much wider confidence intervals. Precision of an estimator for R−1(p) depends on sample size and FPF range. With limited resources (sample size), widening the range of FPF will increase precision of the corresponding predictiveness curve estimate. However, flexibility of the ROC curve estimate is compromised. This issue of bias versus variance trade-off is typical in statistical modeling. Also note that the precision of the R−1(p) estimator tends to be larger for a marker with better predictive accuracy, when the predictiveness curve is steep. For a marker with very weak predictive strength such that the predictiveness curve is very flat at risk threshold p, it is not essential to estimate R−1(p) with high precision since the marker is not going to be helpful for predicting.

Table 3.

Average length for the bootstrap confidence intervals of the predictiveness curve estimators.

| Method | R(v1) | R−1(0.1) | R(v2) | R−1(0.3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: μ = 0.5, v1 = R−1(0.1) = 0.074, v2 = R−1(0.3) = 0.886 | |||||

| nD = nD̄ = 250 | PROC1 | 0.051 | 0.26 | 0.058 | 0.18 |

| PROC2 | 0.065 | 0.42 | 0.060 | 0.26 | |

| nD = nD̄ = 500 | PROC1 | 0.038 | 0.19 | 0.045 | 0.13 |

| PROC2 | 0.047 | 0.27 | 0.046 | 0.18 | |

| Model 2: μ = 0.8, v1 = R−1(0.1) = 0.232, v2 = R−1(0.3) = 0.808 | |||||

| nD = nD̄ = 250 | PROC1 | 0.047 | 0.21 | 0.065 | 0.11 |

| PROC2 | 0.057 | 0.29 | 0.070 | 0.17 | |

| nD = nD̄ = 500 | PROC1 | 0.035 | 0.15 | 0.051 | 0.081 |

| PROC2 | 0.041 | 0.19 | 0.053 | 0.11 | |

| Model 3: μ = 1.2, v1 = R−1(0.1) = 0.396, v2 = R−1(0.3) = 0.770 | |||||

| nD = nD̄ = 250 | PROC1 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.082 | 0.073 |

| PROC2 | 0.045 | 0.26 | 0.097 | 0.14 | |

| nD = nD̄ = 500 | PROC1 | 0.029 | 0.14 | 0.064 | 0.058 |

| PROC2 | 0.032 | 0.16 | 0.074 | 0.086 | |

partial binormal ROC modeling with t ∈ (0.01, 0.99)

partial binormal ROC modeling with t ∈ (0.50, 0.99) for estimating R−1(0.1) and R(v1) for v1 = R−1(0.1), and t ∈ (0.01, 0.50) for estimating R−1(0.3) and R(v2) for v2 = R−1(0.3)

In practice, it is up to the investigator to make a choice between precision and robustness given available resources or to increase sample size. For example, for a marker with moderate predictive strength in our simulation models, average CI length is around 10% for R−1(p) at p = 0.30 for sample size 500 when FPF ranges from (0.01 to 0.99). This is fairly informative. We use a sample size of 500 in our illustration of PSA as a predictive marker for prostate cancer that is described next.

5. Markers for Prostate Cancer

We illustrate the methodology using data from the placebo arm of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (Thompson et al., 2006). Almost all subjects, 5519, in the cohort underwent prostate biopsy at the end of the study and thus had prostate cancer disease status available. 21.9% of men were found to have prostate cancer. The marker, PSA value prior to biopsy, is available for every subject. Our goal is to evaluate PSA as a risk prediction marker for diagnosis of prostate cancer from the biopsy. To illustrate application of our methodology to a nested case-control sample, we randomly sampled 250 cases and 250 controls from the cohort and pretend that PSA is only measured for these 500 subjects but not for the rest of the cohort.

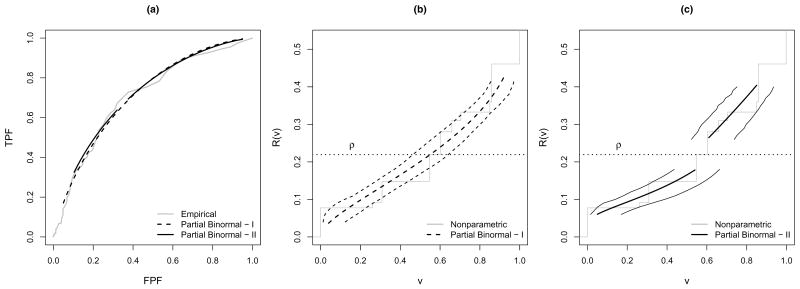

Given a low risk threshold of 10% and a high risk threshold of 30%, our main interest is to estimate R−1(0.10) and 1 − R−1(0.30), the proportions of subjects falling into the low and high risk ranges. We considered two ways to fit the partial binormal ROC curve, that prioritize precision and flexibility respectively. First, we fit one concave partial ROC curve to provide estimates for both R−1(0.10) and 1 −R−1(0.30). To include most of the available data in the interval while avoiding problems due to sparse data at the boundary, we choose the FPF range t ∈ (0.05, 0.95). This guarantees at least 12 controls with data beyond the corresponding risk threshold estimate. The estimated partial ROC curves are displayed in Figure 3(a). Also displayed is the empirical ROC curve (Obuchowski, 2003). The two in general agree well with each other.

Figure 3.

(a) (Partial) ROC curves for PSA (I: t ∈ (0.05, 0.95), II: range of t determined by R−1(p) ± 0.5) and (b)(c) partial predictiveness curves for PSA estimated from the nested case-control study and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals for R−1(p) (range of FPF for partial binormal ROC fitting is (0.05, 0.95) in (b) and determined by R−1(p) ± 0.5 in (c)).

We then estimate the corresponding partial predictiveness curve for PSA plugging in ρ̂ estimated from the parent cohort. The partial predictiveness curve with its 95% confidence intervals (taking variablity in ρ̂ into account) are displayed in Figure 3(b), Also displayed is the nonparametric predictiveness estimate, R̃(v) vs v, under the monotone increasing risk assumption. This curve is generated by estimating P̃ (D = 1|Y) using isotonic regression as described below, estimating FD and FD̄ empirically with F̃D and F̃D̄, calculating F̃= ρ̂F̃D +(1−ρ̂)F̃D̄, and R̃(v) = P̃ {D = 1|Y = F̃−1(v)}. Again, the partial predictiveness curve derived from the partial binormal ROC models appears to be similar to the nonparametric curve.

Table 4 presents corresponding estimates of R−1(0.1) and 1 −R−1(0.3). First, based on ρ̂ estimated from the phase-one cohort (ρ̂= 21.9%), 20.5% subjects in the population are classified as low risk, 26.4% classified as high risk. Confidence intervals are constructed either treating disease prevalence as fixed or taking variability in ρ̂ into account. In this example, the parent cohort is much larger than the case-control sample (around 10 times larger), so variability in ρ̂ has a very small impact on the width of these CIs. Observe that the widths of the confidence intervals are around 18% for estimating R−1(0.10) and 15% for estimating 1 − R−1(0.30), reasonably tight from a clinical point of view.

Table 4.

Estimates of the predictiveness for PSA. Estimates are based on partial binormal ROC models. Confidence intervals are constructed using percentiles of bootstrap distribution.

| PROC1 | PROC2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R−1(0.1) | 1 − R−1(0.3) | R−1(0.1) | 1 − R−1(0.3) | |||||

| Est | 95% CI | Est | 95% CI | Est | 95% CI | Est | 95% CI | |

| ρ = 21.9* | 20.5 | (11.8,29.2) | 26.4 | (20.5, 34.1) | 23.4 | (13.7, 35.1) | 32.7 | (18.8, 40.9) |

| ρ = 21.9† | 20.5 | (12.0, 29.6) | 26.4 | (19.9, 34.8) | 23.4 | (13.1, 35.7) | 32.7 | (20.2, 42.5) |

| Sensitivity Analysis | ||||||||

| ρ = 20.87* | 22.5 | (13.8, 31.2) | 23.5 | (18.0, 30.7) | 26.5 | (15.8, 36.7) | 29.9 | (17.8, 39.3) |

| ρ = 23.05* | 18.7 | (9.0, 27.2) | 29.4 | (23.5, 37.6) | 20.5 | (11.6, 33.7) | 35.4 | (22.9, 44.1) |

| ρ = 18.53* | 27.5 | (18.3, 35.3) | 17.3 | (11.3, 24.2) | 33.9 | (21.4, 40.5) | 23.5 | (12.4, 33.4) |

| ρ = 25.78* | 14.9 | (6.0, 22.8) | 36.7 | (30.0, 45.3) | 14.3 | (7.7, 30.5) | 41.7 | (28.6, 49.0) |

treating disease prevalence as fixed

taking variability in disease prevalence estimate into account

partial binormal ROC fitting with FPF ∈ (0.05, 0.95)

partial binormal ROC fitting with range of FPF determined by R−1(p) ± 0.5

When flexibility of the curve is of major concern, a second strategy can be employed for estimating the predictiveness of PSA at the low and high risk thresholds. Two concave binormal partial predictiveness curves are fitted separately at the low and high ends of the domains for v. The ranges of false positive fractions (FPF) for the corresponding partial ROC curve are (0.38, 0.95) and (0.10, 0.32). Our strategy for choosing these ranges is described as follows.

For the high risk threshold, pH, and analogously for the low risk threshold, pL, we require that the FPF corresponding to the risk threshold is an interior point of the domain of the partial ROC curve. As described below, we first fit a non-parametric risk model to the data, and use to denote the fitted value for the ith subject. We then choose as the upper limit of the ROC domain the estimated FPF corresponding to a slightly lower risk value, . Similarly, we chose as the lower limit of the ROC domain the estimated FPF corresponding to a slightly higher risk values, . We used Δ = 0.05, although larger values could certainly be employed. To avoid problems due to sparse data at the boundary, if the lower FPF limit computed above was smaller than 0.05, it was changed to 0.05, and if the upper limit calculated above was larger than 0.95, it was changed to 0.95.

The estimated partial ROC curves are displayed in Figure 3(a). They agree fairly well with the empirical ROC curve and the partial ROC curve with t ∈ (0.05, 0.95). The corresponding partial predictiveness curve for PSA plugging in ρ̂ estimated from the parent cohort, with its 95% percentile bootstrap confidence interval (with variability in ρ̂ taken into consideration) are displayed in Figure 3(c). Compared to Figure 3(b), confidence intervals are wider with reduced range of FPF. The width of CIs for R−1(0.10) and 1 − R−1(0.30) are around 22% (Table 4). Compare the results for the two partial ROC curve fitting strategies in Table 4. Estimates of R−1(0.10) and 1 − R−1(0.30) shift upward by 3% and 6% respectively when the more flexible strategy is employed. Still, they fall into the 95% CIs based on the curve with the wider FPF range. In practice, if desired precision is of major concern, a wide FPF range is favored. To further increase precision while maintaining flexibility requires a larger sample size.

Note that in practice, when we don’t have a large cohort available for precise estimation of the disease prevalence, sensitivity analysis with varying ρ becomes important. Using our data as an example, the impact of varying perturbations of ρ are examined (Table 3). First we plug in ρ = 20.87% and 23.05%, which correspond to the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval for disease prevalence based on the cohort. When a bigger ρ is entered, we get a larger estimate of 1−R−1(0.30) and smaller estimate of R−1(0.10), although changes in these estimates are not big here (around 3% for both partial ROC curve fitting strategies). Next we increase the perturbation in ρ and plug in ρ = 18.53% and 25.78%, which correspond to lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence interval for disease prevalence if a cohort with 500 subjects is used for estimating prevalence. This time the magnitude of the predictiveness estimates changes quite a lot (around 5–10%). This demonstrates the value of a two-phase design for biomarker evaluation when ρ is estimated precisely from a large cohort while the novel marker Y is measured only for a case-control subset. We also see the value of a sensitivity analysis when an accurate estimate of prevalence is not available.

Finally we describe the algorithm used to fit the non-parametric risk model that incorporates the monotone increasing risk assumption. It involves two steps: (a) We compute P (D = 1|Y, Sampled) from the case-control sample using isotonic regression with the pool-adjacent-violators algorithm (Barlow et al., 1972). Specifically, let y1, …, yU be the unique values for Y in the case-control sample in increasing order. These comprise the initial blocks of the data. The unrestricted MLE of P (D = 1|Y = y, Sampled) within each block is computed as the observed proportion of diseased subjects in that block. Next, estimators within adjacent blocks are compared. If estimators from a pair of adjacent blocks do not increase, the two blocks are pooled and the estimator is recomputed. This procedure of comparison and blocking continues until the sequence of proportions is non-decreasing. At the conclusion of the procedure, the restricted MLE, P̃ (D = 1|Y = yj, Sampled), is the proportion of diseased subjects within the block containing yj; (b) We estimate the population risk function according to Bayes’ theorem P̃ (D = 1|Y)/P̃ (D = 0|Y) = {P̃ (D = 1|Y, sampled)/P̃(D = 0|Y, sampled)} (nD̄/nD) {ρ̂/(1 − ρ̂)}, and obtain a nonparametric risk estimate for every subject in the case-control sample , i=1,…, nD+nD̄.

6. Discussion

Classification accuracy is usually considered to be an intrinsic property of a marker because it does not depend on the population-specific disease prevalence. Predictiveness, on the other hand, integrates classification accuracy and disease prevalence (Pepe et al., 2008a) and characterizes the risk prediction capacity of the marker in a particular population. In this paper, we show the one-to-one relationship between the ROC curve and the predictiveness curve when disease prevalence is fixed. The latter has been proposed as a graphical tool for evaluating a continuous risk prediction marker. We developed methodology for estimating the predictiveness curve based on a parametric ROC model using a case-control study design. The idea of estimating an ROC curve first seems very natural in the retrospective setting considering that criteria for classification accuracy are defined conditional on disease status. The availability of a wide variety of methods for estimating a parametric ROC curve makes this approach even more appealing. We note that the parametric ROC curve methodology can be applied to a cohort study as well by plugging in the sample prevalence.

The main limitation associated with assuming a parametric ROC model, however, is lack of flexibility in the predictiveness curve estimator, especially at the boundary. Estimating a partial predictiveness curve from a partial ROC curve holds promise for resolving this issue. At the same time, it allows use of the most popular parametric ROC model, the binormal ROC model, which may not be concave over the whole range of FPF but can be restricted to be concave in the certain regions. As we have pointed out, an alternative semi-parametric method for predictiveness curve estimation is to fit a risk model using logistic regression and to estimate the marker distribution within cases and controls separately (Huang and Pepe, 2008b, c). This is also an appealing approach since logistic regression is widely used in epidemiological studies. On the other hand, the ROC curve based method has some desirable properties that the logistic regression method lacks. First, the ROC curve estimation method is rank invariant so it does not matter on what scale the marker is measured, whereas fitting of a parametric risk model depends on the scale of the marker measure. Second, the ROC curve based method is natural when considering data from heterogeneous or multiple populations. When a marker’s capacity to distinguish cases from controls is invariant across populations, existing methods can be applied to estimate the common ROC curve using data from different populations (Janes and Pepe, 2008b, c; Huang and Pepe, 2008a; Huang et al., 2008). This together with population-specific prevalences lead to population-specific predictiveness curve estimates that are more efficient than those estimated from individual populations. Finally, since the ROC curve has been the gold standard for biomarker evaluation for decades, researchers may tend to plot it together with the predictiveness curve when they are interested in examining a marker from multiple points of view. While a parametric ROC model is fitted, which is fairly common in practice, deriving the predictiveness curve from it ensures the two curves are estimated under compatible model assumptions.

Some extensions of our methods should be considered. The methods can easily be extended to compare points on predictiveness curves for different markers. When predictiveness curves in subpopulations are of interest, we can estimate the covariate-specific ROC curve using existing ROC regression methods (Alonzo and Pepe, 2002; Pepe and Cai, 2004; Cai and Moskowitz, 2004) and derive the corresponding covariate-specific predictiveness curve by plugging in disease prevalence for the subpopulation. Here we have focused on disease status at a fixed point in time. When subjects are observed over time, the time dimension may make things more challenging especially if there is censoring. Methods to incorporate the time dependence in an event time setting requires further investigation.

Pepe et al. (2008a) suggested that to evaluate a risk prediction marker, besides estimating its predictiveness, it is also helpful to provide information about the fractions of cases and controls identified as high (low) risks in order to assess the effect of correct and incorrect treatment decisions based on the risk marker. For a given risk threshold p, the true and false positive fractions are defined as TPF(p) = P {Risk(Y) > p|D = 1} and FPF(p) = P {Risk(Y) > p|D = 0}. Based on arguments similar to those in Theorem 1, it can be shown that the curve TPF(p) vs p, can be represented as a plot of ROC(t) vs ρROC′(t)/{ρROC′ (t) + (1 − ρ)}, while the curve FPF(p) vs p, can be represented as a plot of t vs ρROC′ (t)/{ρROC′ (t) + (1 − ρ)}. So the rank-invariant parametric ROC curve based strategy developed in this work can be readily applied to estimate these classification performance curves as well for full evaluation of a marker.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to reviewers for constructive comments that lead to substantial improvement to the paper. The authors thank Dr Holly Janes, Dr Yingye Zheng, and Dr Ziding Feng for helpful discussions and comments. Support for this research was provided by NIH grants GM-54438 and NCI grants CA86368.

7. Appendix

Proof of Theorem 2

Let v* be the x-coordinate of the point where the predictiveness curve and the prevalence curve cross, i.e. R(v*) = ρ. Let t* be the value corresponding to v*, i.e. 1 − (1 − ρ)t* − ρROC(t*) = v*. Then

Also we have

Now look at the function ROC(t)−t, its derivative is ROC′(t)−1. For a concave ROC curve, ROC′ (t) is monotone decreasing such that ROC′ (t) − 1 > 0 for t < t* and ROC′ (t) − 1 < 0 for t > t*. So the maximum of ROC(t) − t is achieved at t*, which completes the proof.

References

- Alonzo TA, Pepe MS. Distribution-free ROC analysis using binary regression techniques. Biostatistics. 2002;3 (3):421–432. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SG, Kramer BS, Srivastava S. Markers for early detection of cancer: Statistical guidelines for nested case-control studies. BMI Medical Research Methodology. 2002;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow RE, Bartholomew DJ, Bremner JM, Brunk HD. Statistical Inference Under Order Restrictions: The Theory and Application of Isotonic Regression. Wiley; London: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bura E, Gastwirth JL. The binary regression quantile plot: assessing the importance of predictors in binary regression visually. Biometrical Journal. 2001;43 (1):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cai T, Moskowitz CS. Semi-parametric estimation of the binormal ROC curve for a continuous diagnostic test. Biostatistics. 2004;5(4):573–586. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G, Ratnaparkhi MV. An application of Lomax distributions in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Communications in Statistics. 1993;22:1681–1697. [Google Scholar]

- Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007;115:928–935. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.672402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd L, Pepe MS. Semiparametric regression for the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. JASA. 2003;98(462):409–417. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman DD, Alf E. Maximum likelihood estimation of parameters of signal detection theory and determination of confidence intervals-rating method data. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 1969;6:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman DD, Berbaum KS, Metz CE, Length RV, Hanley JA, Dagga HA. Proper receiver operating characteristic analysis: The bigamma model. Academic Radiology. 1996;4:138–149. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(97)80013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan JP. Signal detection theory and ROC analysis. Academic Press; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Faraggi D, Reiser B. Estimation of the area under the ROC curve. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21(20):3093–3106. doi: 10.1002/sim.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluss R, Faraggi D, Reiser B. Estimation of the Youden index and its associated cutoff point. Biometrical Journall. 2005;47(4):458–472. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200410135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gail MH, Pfeiffer RM. On criteria for evaluating models of absolute risk. Biostatistics. 2005;6(2):227–239. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxi005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse SW, Mantel N. The evaluation of diagnostic tests. Biometrics. 1950;6:399–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Swets JA. Signal detection theory and psychophysics. Wiley; New York: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA. The robustness of the ‘binormal’ assumptions used in fitting ROC curves. Medical Decision Making. 1988;143:29–36. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8800800308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh F, Turnbull BW. Nonparametric and semiparametric estimation of the receiver operating characteristic curve. Annals of Statistics. 1996;24:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. Evaluating the predictiveness of continuous biomarkers. UW thesis. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pepe MS, Feng Z. Evaluating the predictiveness of a continuous marker. Biometrics. 2007;63(4):1181–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Feng Z, Fong Y. UW Biostatistics Working Paper Series. 2008. Borrowing Information across Populations in Estimating Positive and Negative Predictive Values. Working Paper 337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pepe MS. Biomarker Evaluation Using the Controls as a Reference Population. Biostatistics. 2008a doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn029. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pepe MS. UW Biostatistics Working Paper Series. 2008b. Semiparametric and nonparametric methods for evaluating risk prediction markers in case-control studies. Working Paper 333. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pepe MS. UW Biostatistics Working Paper Series. 2008c. Semiparametric methods for evaluating the covariate-specific predictiveness of continuous markers in matched case-control studies. Working Paper 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes H, Pepe MS. Matching in studies of classification accuracy: Implications for bias, efficiency, and assessment of incremental value. Biometrics. 2008a;64(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes H, Pepe MS. Adjusting for covariates in studies of diagnostic, screening, or prognostic markers: an old concept in a new setting. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008b;168(1):89–97. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes H, Pepe MS. Adjusting for covariate effects on classification accuracy using the covariate-adjusted receiver operating characteristic curve. Biometrika. 2008c doi: 10.1093/biomet/asp002. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Metz CE, Nishikawa RM. A receiver operating characteristic partial area index for highly sensitive diagnostic tests. Radiology. 1996;201:745–750. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax HS. Business failure; Another example of the analysis of failure data. JASA. 1954;49:847–852. [Google Scholar]

- McClish DK. Analyzing a portion of the ROC curve. Medical Decision Making. 1989;9:190–195. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8900900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz C, Herman BA, Shen JH. Maximum likelihood estimation of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves from continuously distributed data. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:1033–1053. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980515)17:9<1033::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz CE, Pan X. “Proper” binormal ROC curves: Theory and maximum likelihood estimation. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 1999;43:1–33. doi: 10.1006/jmps.1998.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obuchowski NA. Receiver operating characteristic curves and their use in radiology. Radiology. 2003;229:3–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291010898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, D’Agostine RB, Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27(2):157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS. An interpretation for the ROC curve and inference using GLM procedures. Biometrics. 2000;56:352–359. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS. The Statistical Evaluation of Medical Tests for Classification and Prediction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Cai T. The analysis of placement values for evaluating discriminatory measures. Biometrics. 2004;60:528–535. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2004.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Etzioni R, Feng Z, Potter JD, Thompson ML, Thornquist M, Winget M, Yasui Y. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;93(14):1054–1061. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Feng Z, Huang Y, Longton GM, Prentice R, Thompson IM, Zheng Y. Integrating the predictiveness of a marker with its performance as a classifier. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008a;167(3):362–368. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Feng Z, Janes H, Bossuyt PM, Potter JD. Pivotal evaluation of the accuracy of a biomarker used for classification or prediction: standards for study design. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008b doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn326. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson ML, Zucchini W. On the statistical analysis of ROC curves. Statistics in Medicine. 1989;8:1277–1290. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780081011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson IM, Pauler Ankerst D, Chi C. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98:529–534. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosteson ANA, Begg CB. A general regression methodology for ROC curve estimation. Medical Decision Making. 1988;3:204–215. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8800800309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou KH, Hall WJ. Two transformation models for estimating an ROC curve derived from continuous data. Journal of Applied Statistics. 2000;27:621–631. [Google Scholar]

- Wieand S, Gail MH, James BR, James KL. A family of nonparametric statistics for comparing diagnostic markers with paired or unpaired data. Biometrika. 1989;76:585–592. [Google Scholar]

- Youden Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(1):32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]