1. INTRODUCTION

Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS) also known as velocardiofacial or DiGeorge syndrome, is the most common chromosomal microdeletion in humans, with an incidence of 1 in 2000–4000 live births (Tezenas Du et al., 1996; Shprintzen. 2000). In addition to congenital abnormalities and cognitive deficits in childhood (Shprintzen et al., 1981; Golding-Kushner et al., 1985), a substantial proportion of affected individuals develop major psychiatric illnesses in adolescence/early adulthood.

The most significant of the psychiatric illnesses seen in 22q11DS are the schizophrenia spectrum disorders, occurring in 10–25% of affected individuals, beginning in late adolescence/early adulthood; also seen are bipolar illness and major depression, which develop in 10–15% of these individuals (Shprintzen et al., 1992; Pulver et al., 1994; Papolos et al., 1996; Murphy et al., 1999). Overall, it is estimated that 25–40% will suffer from a major psychiatric disorder, with up to 60% experiencing a major or minor psychiatric disorder (Bassett et al., 2005). Since only 3% of individuals with learning disabilities/mental retardation are thought to develop a psychotic illness (Fraser et al., 1994), the relationship between schizophrenia and 22q11DS is unique and remarkable. Understanding the neural underpinnings of neurocognition and psychosis in 22q11DS should enable better understanding of the neurodevelopmental processes occurring in schizophrenia in the general population, since there is preliminary evidence that the course of schizophrenia in individuals with 22q11DS is similar to that seen in the general population (Bassett et al., 2003).

Among the neurodevelopmental abnormalities in children with 22q11DS is a markedly high frequency of cognitive deficits (80–100%), with most having an IQ between 70–80 (Swillen et al., 1997; Gerdes et al., 1999; Moss et al., 1999; Woodin et al., 2001). We have previously reported that children with the deletion have deficits in sustained attention, executive function and verbal memory, paralleling the deficits seen in individuals with schizophrenia and those at high-risk for the disorder (Lewandowski et al., 2007). Quantitative MRI studies in children with 22q11DS (prior to the onset of psychosis) have shown wide-spread gray matter reductions, mainly in the posterior and temporal cortices, the cerebellum and the hippocampus, with relative preservation of the frontal lobes (Eliez et al., 2000; Eliez et al., 2001; Simon et al., 2005; Debbane et al., 2006). In contrast, in individuals deemed to be at high-risk (offspring of individuals with schizophrenia) and ultrahigh-risk (prodromal) for the disorder in the general population, the most consistent neuroimaging findings are loss of gray matter in the anterior cingulate gyrus, medial temporal lobe and the prefrontal cortices (Keshavan et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2008). More studies are needed in these different groups to determine similarities and differences in these vulnerable populations.

A small number of cross-sectional studies have provided preliminary data that suggest that the relative increases/decreases in gray matter can be associated with lower IQ and behavioral abnormalities in children with 22Q11DS (Bearden et al., 2004; Antshel et al., 2005; Kates et al., 2005; Campbell et al., 2006; Kates et al., 2006; Deboer et al., 2007). A recent study found that a reduction in the cingulate gyrus was associated with poor executive function (Dufour et al., 2008). However, there has been no one study thus far that has examined the relationship between the specific neurocognitive measures that are thought to be highly relevant to neurocognition in schizophrenia, such as sustained attention, executive function, verbal memory (Kern et al., 2004) and the gray matter volumes, in children with 22q11DS.

We set out to perform an integrative study of the neuropsychological and brain structural findings in children with 22q11DS, to determine the neural correlates of neurocognition. Our hypotheses, based on the literature, were that children with 22q11DS would have reductions of gray matter in the parietal, temporal and occipital regions of the cortex and the cerebellum, as well as relative preservation of gray matter in the frontal lobes. We also hypothesized that the volumetric changes in brain regions that are important for neurocognitive tasks such as the temporal, parietal and frontal lobes and the cerebellum would be correlated with sustained attention, executive function and verbal working memory, providing evidence that alterations of brain structure are accompanied by abnormalities in neurocognition, in childhood. The relationship between such findings and psychotic illness would need further longitudinal studies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Subjects

The participants were 22 children with 22q11DS (mean age 12.8 years, SD=2.14, age range 9 years to 16 years and 9 months) and 16 age- and gender- matched control subjects (mean age 12.89 years, SD=2.04, age range from 9 years 9 months to 16 years 3 months). No significant age difference was found between the 22q11DS and control subjects. The 22q11DS sample included 15 males and seven females and the control group consisted of 10 males and six females. The ethnicity of the sample, inclusive of patients and controls, was 90% Caucasian and 10% African American.

All 22q11DS participants had fluorescence in-situ hybridization confirmation of their diagnosis. The subjects were recruited from the Medical Genetics Clinics of Wake Forest University Health Sciences (WFUHS), Carolinas Medical Center, the local public school system and private pediatric practices in the community. A three-generation pedigree was assessed for the presence of mental illness, learning disabilities or other problems that could indicate family members affected with 22q11DS, or another developmental or genetic disorder (MNB). Control subjects with a personal or family (first-degree relative) history of a psychotic illness, or a personal history of mental retardation/developmental delay or multiple congenital anomalies were excluded from the study. For children with 22q11DS, the occurrence of psychosis in family members affected by 22q11DS was not considered as an exclusion criterion. However, the occurrence of psychosis in family members who did not have 22q11DS resulted in exclusion. None of the patients or control subjects had a psychotic illness at the time of the study. Control subjects were recruited from the local public school system. Those with an IQ over 115 were excluded as control subjects, to enable reasonable comparison between the patient and control groups. Forty six percent of the patients and 44% of the control participants were diagnosed with AD/HD, with 23% and 25% respectively prescribed medication for AD/HD at the time of the assessment. The high percentage of control subjects with AD/HD was due to the fact that many of the children who participated in the study did so because they had experienced learning difficulties, thus providing the parents with an impetus to obtain more information through psychoeducational testing offered as part of the study. Since AD/HD is one of the more common causes of learning difficulties, it is not surprising that we saw such a high incidence of this in the control subjects. This high incidence of AD/HD in the control participants avoids potential confounding results and poses an advantage.

Control and patient subjects received a targeted examination to detect dysmorphic features (VS). The institutional review boards of all the medical centers where the study was conducted approved the study.

2.2. MRI Studies

Imaging studies were performed at WFUHS, with a General Electric (GE) 1.5 Tesla Signa System running 8.4 M4 software. A set of sagittal scout images (2D fast spin echo, TR=2,500 ms, echo time (TE) =88 ms, FOV=240 mm, approximately 10 slices, slice thickness=5 mm, slice gap=1.5 mm, NEX=1, matrix=256×128, scan time=50s) were collected to verify patient position, cooperation and image quality. A set of T2 weighted axial images was then collected covering the whole brain (2D fast spin echo, TR=3000 ms, TE=36 ms and 96 ms, echo train length (ETL) =8, FOV=26×26, approximately 110 slices, slice thickness=3 mm, slice gap=0 mm, NEX=1, matrix=256×192). Three-dimensional spoiled gradient echo imaging (SPGR) was performed in the coronal plane (SPGR sequence, TR=25ms, TE=5ms, nutation angle=40°, FOV=180 mm in the phase encoding direction and 240 mm in the read direction, slice thickness=1.5 mm, NEX=1, matrix=256×192, scan time=10 minutes and 18 seconds) to obtain 124 images covering the entire brain.

2.3. Voxel-based morphometric (VBM) analyses- (DG, KP and MSK)

A whole brain voxel-wise analysis using an optimized voxel-based morphometry approach was run using statistical parametric mapping version 5 (SPM5) that assesses differences in gray matter concentration at a microstructural level across the whole brain to identify areas of interest (Ashburner et al., 2000). We used a pediatric template (CCHMC2 template, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH) to normalize the images because of the age range of study subjects. The CCHMC2 template was generated using 148 healthy children, 69 boys and 79 girls, with an age range of 5–18 years, mean of 11.32, SD of 3.49 years (Wilke et al., 2002). The CCHMC2 template avoids the bias caused by the normalization of pediatric images to the MNI template that represents mainly the adult brain. Thus, errors in image registration and erroneous group differences are averted.

MR images were segmented and extracted in native space (to remove scalp, skull tissue and dural venous sinus voxels). Extracted gray matter segments were normalized to the gray matter templates, allowing optimal normalization of gray matter and smoothed by convolving with a 12 FWHM Gaussian kernel. Unmodulated images were analyzed and thresholded to identify clusters of significance. Since cluster-level significance is known to produce false positive results, only voxel-level results were used (Ashburner et al., 2000; Honea et al., 2005). We obtained the reciprocal Talairach Deamon and AAL atlas coordinates to classify the locations of significance.

Based on the VBM analytical findings, we extracted gray matter volumes of the regions of interest, using the modulated images. We used the WFU PickAtlas program to mask the regions of interest. Using the modulated images with volumetric data, number of voxels that subtend within the mask and the proportion of gray matter within each voxel were used to calculate the volume. Compared to manually defined regions of interest, the masks used in the WFU Atlas have been demonstrated to reliably include the regions of interest (Maldjian et al., 2003). These quantitative data were then used for statistical analyses to confirm the VBM findings, as well as to determine the relationship between the neuropsychological and MRI findings.

2.4. Neuropsychological Assessment (TRK and JK)

Intelligence testing was performed with the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) using version III for earlier subjects and IV for subjects who were enrolled later. In order to minimize inequities between the two versions, we report the Verbal Comprehension Factor /Perceptual Organization Factor from the WISC- III and the Verbal Comprehension Index/Perceptual Reasoning Index from the WISC-IV. We assessed attention/vigilance, verbal learning and reasoning and problem-solving, domains that are frequently impaired in individuals with schizophrenia, based upon the NIMH Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) task force recommendations (Kern et al., 2004). Executive functioning was measured with the perseverative errors and conceptual level response indices from the Wisconsin Card Sort Test (WCST) (Chelune et al., 1986). Sustained attention was assessed with the identical pairs (IP) and the AX conditions of the Continuous Performance Test (CPT) (Cornblatt et al., 1985; Erlenmeyer-Kimling et al., 2000). In addition, we assessed verbal learning and memory with the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT-C) (Delis et al., 1994). A semistructured interview was administered to the caregivers to ascertain psychiatric diagnoses (C-DISC), based on the DSM-IV criteria for mental disorders (National Institutes of Mental Health 2000).

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.5.1. VBM Analyses

We first conducted estimation of the design using ANCOVA (age and gender as covariates). Then, we set up the contrasts between the groups using independent sample t-tests. Extent threshold was set to uncorrected p = 0.001 and the minimum cluster size allowed was 25 voxels. We report on the peak voxel-level p value within these clusters, false discovery rate (FDR) corrected for multiple comparisons. Minimum acceptable FDR was set to p<0.05.

2.5.2. Region of Interest Analyses with the Extracted Volumes

In order to examine whether the 22q11DS and control groups differed on gray matter volumes, ANCOVA was performed with age, sex, and total intracranial volume as covariates. The results and effect sizes (eta2) are presented for each analysis. This statistic indicates the proportion of the total variance in the sample accounted for by each effect (note that eta2 was selected rather than the partial eta2 statistic given the limitations described by Levine & Hullett (Levine. 2002) . Following Cohen an effect size of 0.35 is considered large, 0.15 is considered medium and 0.02 is considered small (Cohen. 1988).

We next examined the relationship of gray matter volumes with intellectual ability, sustained attention, executive functioning and verbal learning and memory using hierarchical regression analyses. In each analysis, a measure of neurocognitive performance was included as the criterion. Sex, age, and total intracranial volume were entered at the first step, regional brain volume at the second step, group at the third step and the group x brain volume interaction at the final step. The interaction term allowed us to examine whether the relationship between brain volume and neurocognitive performance was different for the 22q11DS and control groups.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Qualitative MRI Analysis

An MRI abnormality was seen in 17/22 of the 22q11DS subjects on routine MRI analysis; three had subcortical white matter densities, one had an Arnold-Chiari type 1 malformation; 14 had a cavum septum pellucidum (CSP) of more than 4 mm in size (one subject had both a CSP and the Arnold-Chiari malformation). Four of the 16 controls had an MRI finding of a CSP of over 4 mm. There were no significant differences between the 22q11DS and control groups in the occurrence of any MRI finding or a CSP (p=0.09 and 0.2 respectively, Fisher’s exact test). However, all of the CSPs that were large in size (25–50 mm) occurred only in the 22q11DS group (n=7/22) [p=0.03].

3.2. VBM Analysis

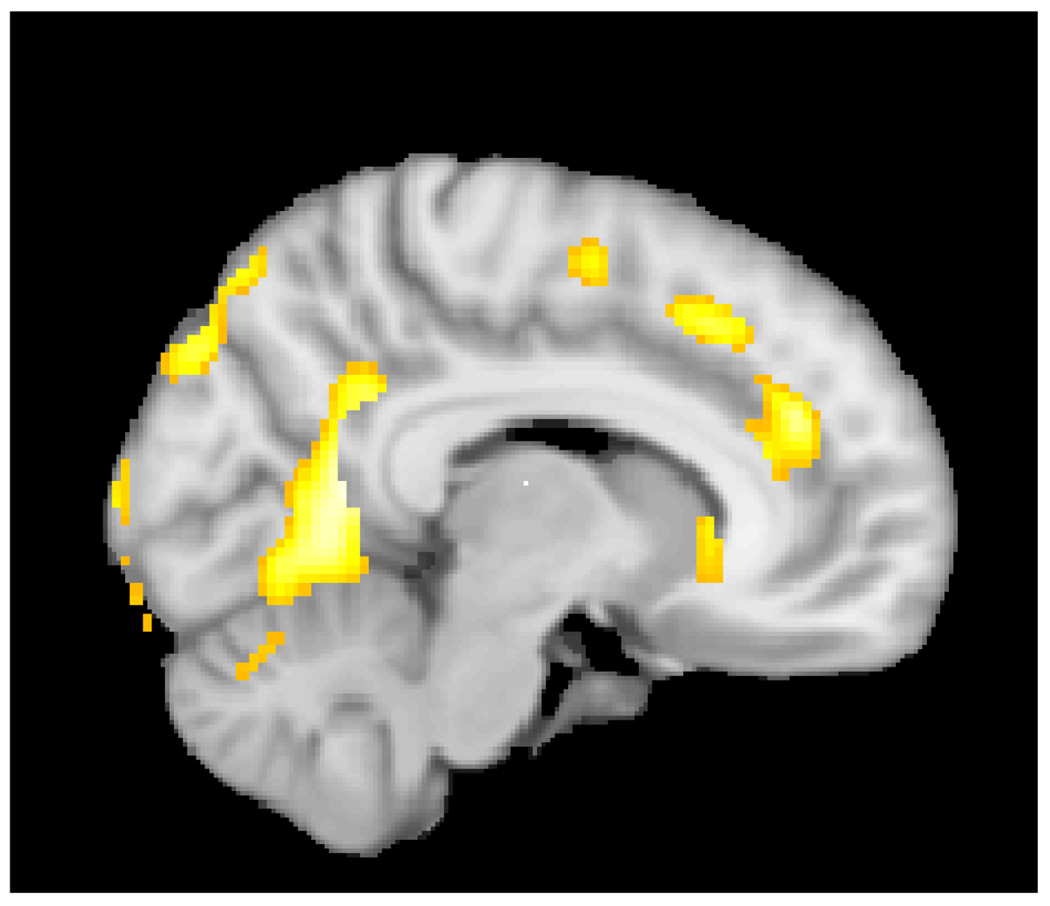

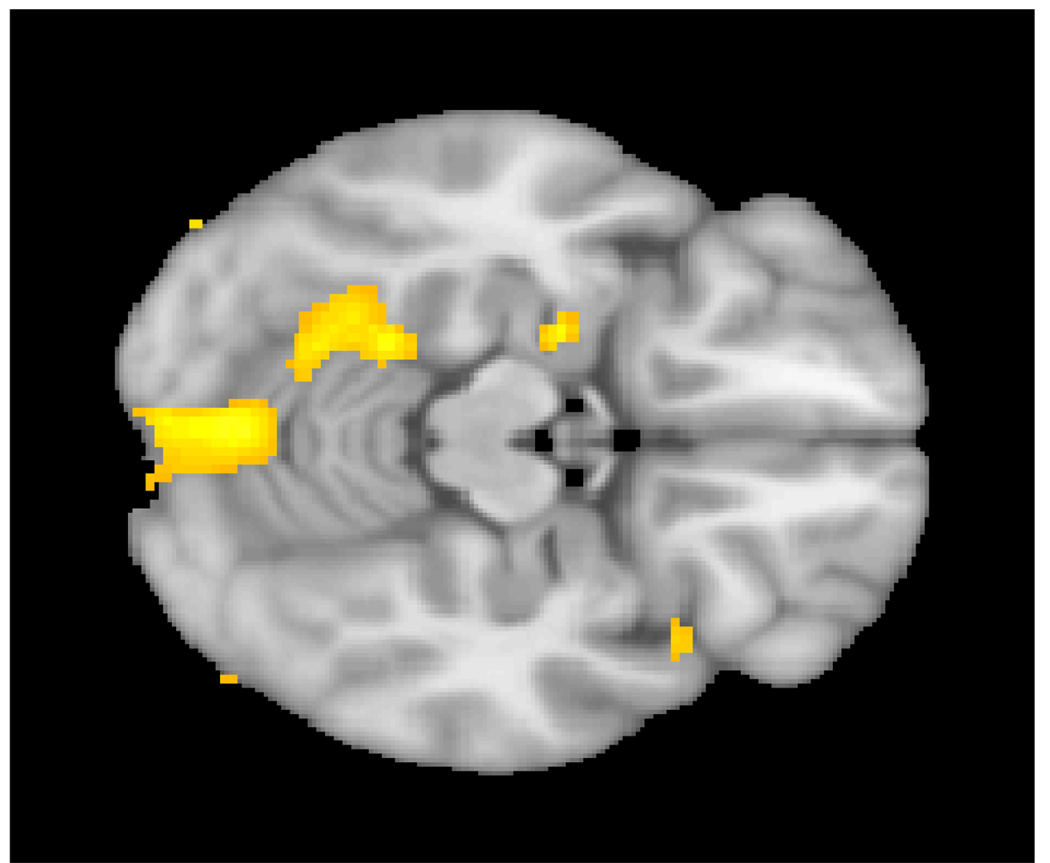

Subjects with 22q11DS had significantly reduced gray matter in several regions of the brain, when compared to the control subjects (Table 1, Figure 1–Figure 2). Specifically, the anterior and middle cingulate gyri, the lingual gyrus, the cuneus and culmen of the cerebellum, the fusiform gyrus, the middle and inferior frontal gyri, the amygdala and the caudate nucleus were volumetrically reduced in the 22q11Ds group, relative to controls.

Table 1.

VBM analyses (voxel-level) of Gray Matter Reductions in children with 22q11DS (n=22) compared to Control Subjects (n=16). Height threshold: T=3.37, extent threshold: k=25 voxels.

| Brain Regions | Cluster Size (1 mm3 voxels) | Talaraich/AAL Atlas coordinates mm | Voxel-level PFDR-corrected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lingual gyrus left | 3282 | −2 | −68 | 0 | 0.001 |

| Cuneus right | 324 | 14 | −86 | 40 | 0.001 |

| Anterior cingulate right | 367 | 12 | 40 | 26 | 0.001 |

| Superior temporal right | 204 | 54 | 2 | 4 | 0.002 |

| Middle cingulate right | 109 | 12 | 20 | 46 | 0.002 |

| Inferior frontal right | 82 | 60 | 6 | 22 | 0.002 |

| Subgyral right | 120 | 50 | −18 | 20 | 0.002 |

| Amygdala left | 86 | −24 | −8 | −14 | 0.003 |

| Middle frontal right | 42 | 48 | 4 | 54 | 0.003 |

| Inferior frontal left | 58 | −46 | 42 | 18 | 0.005 |

| Culmen left | 287 | −20 | −44 | −16 | 0.007 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | 97 | −52 | −58 | 42 | 0.008 |

| Fusiform left | 56 | −52 | 2 | 32 | 0.010 |

| Caudate right | 49 | 10 | 22 | 2 | 0.010 |

Figure 1.

Reduced gray matter in the cingulate gyrus in children with 22q11Ds compared to controls. Also evident are the decrease in gray matter in the occipital regions in the 22q11DS group.

Figure 2.

Reduction in gray matter in the cerebellar regions in children with 22q11DS

3.3. Extracted Volumes Analyses

The total intracranial volume (ICV) in the 22q11DS group was not reduced as compared to the control group (mean ICV in 22q11DS= 1324.1 cc, SD= 169.6 and mean ICV in control group= 1357cc, SD= 176.8, p=0.2). Thus, it was deemed appropriate to partial out variance associated with ICV as well as age and gender, from the correlations of groups and brain volumes (note that in cases of nonrandom assignment, variables that differ between groups cannot be used as covariates, contrary to common wisdom (Miller et al., 2001). We performed ANCOVA on the patient and control groups and were able to confirm the reduced gray matter within the anterior and middle cingulate gyri, areas corresponding to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), the cerebellum, lingual gyrus and the left fusiform gyrus. Additionally, the posterior cingulate and the substantia nigra on both sides and the left subthalamus were also volumetrically reduced in the 22q11DS group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of 22q11DS and control group on gray matter volumes (mm3) with age, sex and intracranial volume as covariates

| Brain Region | 22q11DS group | Control Group | F-value | Effect Size (η2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |||

| Anterior cingulate L | 5575.4 | (614.5) | 5840.7 | (581.1) | 1.56 | 0.035 |

| Anterior cingulate R | 5209.9 | (623.6) | 5701.0 | (634.6) | 6.79* | 0.100 |

| Middle cingulate L | 7501.0 | (773.3) | 8108.6 | (827.3) | 6.40* | 0.135 |

| Middle cingulate R | 8769.3 | (865.8) | 9670.3 | (978.2) | 10.43** | 0.193 |

| Posterior cingulate L | 1237.0 | (148.5) | 1463.9 | (233.3) | 13.61*** | 0.282 |

| Posterior cingulate R | 599.8 | (94.8) | 772.9 | (153.9) | 17.16*** | 0.338 |

| Amygdala L | 778.2 | (85.6) | 786.3 | (117.1) | 0.15 | 0.003 |

| Amygdala R | 1013.0 | (85.4) | 1004.3 | (98.2) | 0.06 | 0.001 |

| Caudate nucleus L | 3142.7 | (439.5) | 3393.6 | (543.8) | 3.06 | 0.075 |

| Caudate nucleus R | 3346.2 | (470.3) | 3414.1 | (524.4) | 0.45 | 0.011 |

| Fusiform L | 8942.6 | (1119.8) | 9524.4 | (958.5) | 6.05* | 0.098 |

| Fusiform R | 9052.8 | (1187.5) | 9533.9 | (1068.0) | 2.51 | 0.024 |

| Pallidum L | 653.5 | (136.5) | 727.9 | (131.7) | 3.49 | 0.090 |

| Pallidum R | 784.4 | (153.7) | 841.4 | (157.7) | 2.30 | 0.058 |

| Subthalamus L | 16.3 | (5.5) | 11.6 | (4.8) | 5.91* | 0.146 |

| Subthalamus R | 11.1 | (4.9) | 10.5 | (3.4) | 0.13 | 0.004 |

| Substantia nigra L | 23.4 | (11.8) | 35.2 | (9.5) | 15.05*** | 0.292 |

| Substantia nigra R | 20.9 | (11.3) | 33.5 | (10.3) | 16.76*** | 0.303 |

| Brodmanns’ area L 9 | 4465.7 | (644.7) | 4901.1 | (828) | 4.34* | 0.109 |

| Brodmann’s area R 9 | 4928.0 | (580.5) | 4639.7 | (734.8) | 3.84 | 0.093 |

| Cerebellum L | 48591.7 | (5716.7) | 52967.2 | (6628.5) | 8.58** | 0.141 |

| Cerebellum R | 48813.6 | (5981.3) | 54645.4 | (6172.5) | 12.25** | 0.143 |

Medium and large effect sizes (η2) are bolded

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Note: corrections for multiple testing were not applied here because these areas were significant at FDR-corrected p<0.05.

3.4. Summary of cognitive data in the 22q11DS group, compared to the control group

The details of the neurocognitive deficits in the 22q11DS group are published elsewhere (Lewandowski et al., 2007), but we wish to emphasize that there were significant differences in IQ between the 22q11DS and control groups. The mean IQ of the 22q11DS children was 73.3 (SD= 11.5) as compared to the control subjects (mean= 106, SD=13.6. t=-8.05). Similarly, there were significant differences between the two groups in sustained attention, executive function and verbal memory, with the 22q11DS group demonstrating worse performance, even after partialling out variance associated with verbal and performance IQ (Lewandowski et al., 2007).

We examined the relationship between gray matter volumes that were significantly different in the 22q11DS group and neurocognitive performance using hierarchical regression analyses (a representation of these are presented in Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5), the 22q11DS patients performed worse than the control group on the neurocognitive measures (note that positive betas indicate superior performance by the control group). We found significant correlations between the volumetric gray matter reductions in the DLPFC, the cingulate gyrus, the cerebellum and tests of higher neurocognition in both the patient and control groups. Other regional gray matter reductions were not associated with the neurocognitive measures in either the 22q11DS or control groups. (Lewandowski et al., 2007).

Table 3.

Relationship of right Brodmann’s area 9 and neurocognitive performance, a representation of the correlations between brain gray matter volumes and neurocognition in this study

| Criterion | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Sex, ICV | Right Brodmann’s area 9 | Group | Interaction | |||||||||

| β | Δr2 | f2 | β | Δr2 | f2 | β | Δr2 | f2 | β | Δr2 | f2 | |

| WISC Verbal comp | -- | 0.243* | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.149* | 0.25 | 0.59 | 0.282*** | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.002 | 0.01 |

| WCST_PE | -- | 0.106 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.039 | 0.05 | 0.41 | 0.145* | 0.20 | −0.14 | 0.016 | 0.02 |

| WCST_CLR | -- | 0.196 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.076 | 0.10 | 0.51 | 0.220*** | 0.43 | −0.02 | 0.000 | 0.00 |

| CPT_AX | -- | 0.234* | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.020 | 0.03 | 0.72 | 0.438*** | 1.40 | −0.04 | 0.001 | 000 |

| CPT_IP | -- | 0.220* | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.044 | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.303*** | 0.70 | −0.01 | 0.000 | 0.00 |

| CVLT 1–5 | -- | 0.189 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.061 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.193** | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.021 | 0.04 |

Medium and large effect sizes (f2) are bolded. Positive β at step 2 indicate larger volume is associated with better cognitive performance, at step 3 indicates better cognitive performance in the control group than in the 22q11DS patient group.

p < 0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Table 4.

Relationship of right posterior cingulate volume and neurocognitive performance

| Criterion | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Sex, ICV | Right posterior cingulate | Group | Interaction | |||||||||

| β | Δr2 | f2 | β | Δr2 | f2 | β | Δr2 | f2 | β | Δr2 | f2 | |

| WISC Verbal comp | -- | 0.243* | 0.32 | 0.55 | 0.298*** | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.129** | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.000 | 0.00 |

| WCST_PE | -- | 0.106 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.067 | 0.08 | 0.44 | 0.115* | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.005 | 0.01 |

| WCST_CLR | -- | 0.196 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.127* | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.161** | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.001 | 0.00 |

| CPT_AX | -- | 0.234 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.132* | 0.21 | 0.71 | 0.320*** | 1.02 | −0.10 | 0.006 | 0.02 |

| CPT_IP | -- | 0.220 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.200** | 0.34 | 0.51 | 0.163** | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.021 | 0.05 |

| CVLT 1–5 | -- | 0.189 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.093* | 0.13 | 0.49 | 0.153** | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.078* | 0.16 |

Medium and large effect sizes (f2) are bolded. Positive β at step 2 indicate larger volume is associated with better cognitive performance, at step 3 indicates better cognitive performance in the control group than in the 22q11DS patient group.

p < 0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Table 5.

Relationship of right cerebellum volume and neurocognitive performance

| Criterion | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Sex, ICV | Right cerebellum | Group | Interaction | |||||||||

| β | Δr2 | f2 | β | Δr2 | f2 | β | Δr2 | f2 | β | Δr2 | f2 | |

| WISC Verbal comp | -- | 0.243 | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.168** | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.232*** | 0.65 | 0.01 | .000 | 0.00 |

| WCST_PE | -- | 0.106 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.042 | 0.05 | 0.46 | 0.141* | 0.20 | 0.15 | .021 | 0.03 |

| WCST_CLR | -- | 0.196 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 104* | 0.15 | 0.53 | 0.183** | 0.35 | 0.14 | .016 | 0.03 |

| CPT_AX | -- | 0.234 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.113* | 0.17 | 0.70 | 0.338*** | 1.08 | −0.05 | .002 | 0.00 |

| CPT_IP | -- | 0.220 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.108* | 0.16 | 0.59 | 0.239*** | 0.55 | 0.22 | .041 | 0.10 |

| CVLT 1–5 | -- | 0.189 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.072 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.173** | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.010 | 0.02 |

Medium and large effect sizes (f2) are bolded. Positive β at step 2 indicate larger volume is associated with better cognitive performance, at step 3 indicates better cognitive performance in the control group than in the 22q11DS patient group.

p <0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

There was no significant difference in the diagnosis of AD/HD or stimulant medication status between the 22q11DS and control groups that could have caused confounding results on the neurocognitive tests.

4. DISCUSSION

Our study examined gray matter volumetric changes in children with 22q11DS and the relation between such changes and neurocognitive performance. Delineating premorbid findings in a high risk group, such as children with 22q11DS, should increase the understanding of the pathogenesis of schizophrenia and other psychoses. This study is focused on the gray matter changes occurring in childhood in 22q11DS and thus the discussion is centered around these findings. Functional MRI studies and structural MRI studies that delineate white matter changes as well as structural changes in adults with 22q11DS are beyond the scope of this article.

Qualitative analysis of the brain images indicated that a CSP was frequent in the 22q11DS group. A CSP is thought to be indicative of maldevelopment of structures bordering it, such as the amygdala and the cingulate gyrus and has been reported both in children with 22q11DS (Mitnick et al., 1994; Bingham et al., 1997; Vataja et al., 1998; Shashi et al., 2004) and adults with 22q11DS who have schizophrenia (Chow et al., 1999; van Amelsvoort et al., 2001). It is said to occur in up to 45% of individuals with schizophrenia in the general population (Shenton et al., 2001), although others report no association between a CSP and schizophrenia or high-risk status (Rajarethinam et al., 2008). We found no significant difference in the frequency of a CSP between the 22q11DS subjects and the control groups; however, remarkably large CSPs (25–50 mm in size, some filling the entire lateral ventricles) occurred exclusively in the 22q11DS subjects (p=0.03). We suggest that a large CSP in children with 22q11DS is likely to be a marker of abnormal neurodevelopment of adjacent structures such as the cingulate gyrus.

A reduction in total intracranial volume (ICV) has been reported in schizophrenia (Vita et al., 2006). Although reduction in ICV have been reported in individuals with 22q11DS (with and without psychosis), careful perusal of such reports indicated that many were not significant (Eliez et al., 2000; Chow et al., 2002; Kates et al., 2004). We did not find a significant difference in ICV between the 22q11DS and controls subjects in our study. However, confounding factors such as a small sample size and a population of controls that are not “typical” could have resulted in this finding in our study.

4.1. Gray matter changes in 22q11DS

Previous reports of morphometric MRI analyses of gray matter in 22q11DS children prior to the development of psychoses, have found reductions in the parietal and occipital lobes, cerebellum, cingulate gyrus, superior temporal gyrus and hippocampus (Usiskin et al., 1999; Eliez et al., 2000; Eliez et al., 2001; Eliez et al., 2001; Kates et al., 2001; Simon et al., 2005; Bearden et al., 2006; Bish et al., 2006; Campbell et al., 2006; Bearden et al., 2009). Relatively preserved gray matter within the frontal lobes and the insula and an increase in the volume of the caudate body have been reported (Sugama et al., 2000; Eliez et al., 2002; Kates et al., 2004; Simon et al., 2005). However, other studies found a trend towards decreased frontal and prefrontal areas, in males with 22q11DS (Kates et al., 2005) and decreased gyrification in the frontal lobes [this study included both children and adults with 22q11DS] (Schaer et al., 2006). We discuss below the VBM and extracted volume analyses in children with 22q11DS, relative to control subjects.

We found significant decreases in the DLPFC gray matter (middle frontal gyrus, Brodmann’s area 9) in children with 22q11DS, contrary to our expectation of preserved frontal lobe gray matter. However, the reduction in the DLPFC was not as robust as gray matter reductions in the cerebellum and cingulate. Although it is thought that in the general population, DLPFC reductions occur later in the trajectory of events on the pathway to psychosis, consistent with the “back to the front” theory of synaptic pruning in adolescence (Rapoport et al., 2005), we have insufficient evidence to suggest this in our patient population, due to the cross-sectional nature of our study. Gray matter losses in the DLPFC, the seat of neurocognitive function in the domains of sustained attention, executive function and working memory (Goldman-Rakic et al., 1991), are reported in schizophrenia (Tandon et al., 2008). Similarly, reductions in DLPFC gray matter have been described in individuals at high-risk of schizophrenia in the general population (Pantelis et al., 2003; Wood et al., 2008).

All subregions of the cingulate gyrus showed gray matter reductions in our cohort of 22q11DS children, consistent with two previous reports (Simon et al., 2005; Campbell et al., 2006). Note that reductions in gray matter within the anterior cingulate have been consistently reported in schizophrenia (Glahn et al., 2008); less frequent are reductions in the middle and posterior cingulate (Wolf et al., 2008). In prodromal individuals, a loss of anterior cingulate gray matter occurred in those that went to develop psychosis, suggesting that such reductions may be predictive of psychosis in ultra high-risk individuals (Pantelis et al., 2003; Wood et al., 2008).

Volumetric gray matter reductions in the cerebellum and lingual gyrus in the 22q11DS group in this study are consistent with previous reports (Eliez et al., 2001), indicating that these reductions are an integral part of the neurodevelopmental abnormalities in 22q11DS. Similar cerebellar gray matter reductions have been described in schizophrenia, but the exact significance remains poorly understood (Shenton et al., 2001). Since the cerebellum is believed to be important in mediating the cognitive deficits seen in schizophrenia (Andreasen et al., 1999), the cerebellar reduction may prove to be important in neurocognition in individuals with 22q11DS.

Previously gray matter reductions of the hippocampus, and increases within the basal ganglia or insula have been reported (Eliez et al., 2002; Simon et al., 2005; Campbell et al., 2006; Debbane et al., 2006; Deboer et al., 2007), while findings regarding the amygdala gray matter volumes have been equivocal (Debbane et al., 2006; Kates et al., 2006; Deboer et al., 2007). A reduction in gray matter in regions of the basal ganglia including the caudate, and the amygdala was detected in our 22q11DS subjects. Such inconsistencies from one study to another may partly be explained by methodological differences (e.g., using total gray matter vs. intracranial volume as a covariate, varying templates for analyses and differences in subjects’ ages). Thus, uniformity of methods should minimize confounding findings.

4.2. Correlations between gray matter changes and neurocognition in 22q11DS

Our study is the first to report that gray matter reductions in the DLPFC, cingulate and cerebellum are correlated with poor performance in executive function, sustained attention and verbal memory, in children with 22q11DS. A few previous studies have examined the relationship between gray matter volumes in 22q11DS and the cognitive deficits seen in childhood. One study reported no correlations of DLPFC reduction with executive function, working memory or facial recognition, in boys with 22q11DS (Kates et al., 2005); however, the control group demonstrated an association between DLPFC reduction and planning and organization (Kates et al., 2005). A second study reported that reduction in hippocampal volume was associated with lower verbal IQ (Deboer et al., 2007). Thinning of the frontal cortex is reported to correlate with cognitive abilities (Bearden et al., 2009). Other studies that have examined the functional correlates of gray matter changes in 22q11DS have concentrated on behavior and minor psychiatric diagnoses, rather than neurocognition (Eliez et al., 2001; Bearden et al., 2004; Campbell et al., 2006; Kates et al., 2006), emphasizing the need for further studies of neurocognition and brain volumes.

Our finding of correlations between the DLPFC gray matter reductions in the 22q11DS group and poor neurocognitive performance, previously unreported, parallels similar reports in individuals with schizophrenia (Antonova et al., 2004) as well as high-risk individuals (Keshavan et al., 2004). We believe that the DLPFC is associated with neurocognition in healthy control subjects as well, since we found a positive correlation between DLPFC volumes and neurocognition in this group.

The anterior cingulate is integral to affect and cognition via its projections to the prefrontal regions (Yucel et al., 2003) and disturbances in cingulate functioning are associated with executive dysfunction in schizophrenia (Rusch et al., 2007), as well as the affective and attentional symptoms seen in high-risk individuals (Wood et al., 2008). Our finding of volumetric reduction in the subregions of the cingulate is similar to previous reports in children with 22q11DS (Simon et al., 2005; Campbell et al., 2006), including as association between the anterior cingulate reductions and cognition (Simon et al., 2005) and cingulate volume and executive function (Dufour et al., 2008), but this is the first study to report correlations between such reductions and performance associated with the cognitive phenotype in schizophrenia, namely executive functioning, sustained attention and verbal working memory.

The cerebellum has been long known to play a critical role in coordination and fine motor control, but recently it has been reported to influence cognitive processes such as planning and problem solving (Schmahmann et al., 1998). Impairment of these functions are thought to underlie the “cognitive dysmetria” seen in schizophrenia (Andreasen et al., 1999). We found reduced cerebellar gray matter was associated with impairments in sustained attention, executive functioning, verbal working memory and IQ in both the 22q11DS and control participants, emphasizing the role of the cerebellum in neurocognition. However, the relationship of the cerebellar gray matter reduction to the development of psychosis associated with 22q11DS is as yet unclear (Eliez et al., 2001; van Amelsvoort et al., 2001; van Amelsvoort et al., 2004). Only one study examined the differences in volume reduction of the cerebellum, in 22q11DS adults with and without schizophrenia and found no differences between the two groups (van Amelsvoort et al., 2004). Longitudinal studies (ongoing in our study) will help determine the relationship between the cerebellar gray matter reductions and schizophrenia.

The finding that the gray matter volume x group interactions generally did not account for increments in variance, suggests that 22q11DS does not moderate the relations between gray matter and neurocognition (i.e., gray matter changes impact neurocognition comparably in the patients and the control subjects). Thus, the marked neurocognitive impairment in 22q11DS appears to be associated with disruptions in neurodevelopment that result in significant gray matter reductions in the patients

We found no associations between gray matter volumes and neurocognition in areas such as the fusiform gyrus and amygdala; areas that are important in other functions such as face recognition (fusiform gyrus) or anxiety (amygdala). Similarly, the lack of correlation between the reduction of the superior temporal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule and cognitive performance may reflect that these areas are critical to other functions, such as language or visual-spatial function.

A small sample size is a limitation to the study, but nonetheless we were able to demonstrate significant effects. In addition, VBM, although widely used, is not ideal to quantify small structures such as the substantia nigra and thus abnormalities of these structures may not be accurately detected (Kennedy et al., 2008). However, we eliminated common confounders of VBM, such as motion artifact; and the age of our study subjects was within 1 SD of the age of the children used to generate the pediatric template data. Thus, we have minimized the cross-registration errors that could be seen as differences in voxel intensities.

One of the strengths of our study is that our 22q11DS subjects are more likely representative of the spectrum of developmental problems that occur in this condition, since they were not ascertained through a pediatric specialty clinic (e.g., psychiatry, cardiology, ENT), but through general genetics clinics, wherein children are evaluated with no bias towards psychological manifestations. We also chose psychological measures that are known to reliably assess the deficits that are central to the neurocognitive phenotype of schizophrenia (Kern et al., 2004). Furthermore, the neuroimaging data is based upon a pediatric template, thereby avoiding the possible confounding effects of an adult template. Finally, we used a convergent approach to morphometric analysis: VBM and the analysis of extracted volumes.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that reductions in gray matter within the cerebellum, the posterior cortices, the cingulate and the DLPFC occur in children with 22q11DS. No areas of gray matter excesses were detected in the 22q11DS group. In both 22q11DS and control subjects, gray matter volumes within the DLPFC, the cingulate and the cerebellum were positively correlated with performance in the domains of sustained attention, executive function and verbal memory, in addition to intelligence, strengthening the concept that these brain regions are important mediators of neurocognition. Longitudinal study of this and similar samples should enhance our understanding of the trajectory of brain development and neurocognition during adolescence, and the relevance of such findings to the development of schizophrenia in later life.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by R01MH78015-01A1 (PI: V. Shashi), R03MH167194-01A2 (PI: V. Shashi) and NARSAD Young Investigator Award (PI: V. Shashi).

We are also indebted to the children with 22q11DS and their families as well as the control subjects and their families for their participation in the study.

We are grateful to Carla M. Johnson for assistance with manuscript editing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures

None of the authors listed has financial or other conflicts of interest related to the material in this manuscript.

References

- Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, O’Leary DS, Miller DD, Wassink T, Flaum M. Defining the phenotype of schizophrenia: cognitive dysmetria and its neural mechanisms. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:908–920. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonova E, Sharma T, Morris R, Kumari V. The relationship between brain structure and neurocognition in schizophrenia: a selective review. Schizophr.Res. 2004;70:117–145. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antshel KM, Conchelos J, Lanzetta G, Fremont W, Kates WR. Behavior and corpus callosum morphology relationships in velocardiofacial syndrome (22q11.2 deletion syndrome) Psychiatry Res. 2005;138:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry--the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11:805–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, Chow EW, AbdelMalik P, Gheorghiu M, Husted J, Weksberg R. The schizophrenia phenotype in 22q11 deletion syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1580–1586. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, Chow EW, Husted J, Weksberg R, Caluseriu O, Webb GD, Gatzoulis MA. Clinical features of 78 adults with 22q11 Deletion Syndrome. Am.J.Med.Genet.A. 2005;138:307–313. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden CE, van Erp GT, Dutton RA, Lee AD, Simon TJ, Cannon TD, Emanuel BS, McDonald-McGinn D, Zackai EH, Thompson PM. Alterations in midline cortical thickness and gyrification patterns mapped in children with 22q11.2 deletions. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:115–126. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden CE, van Erp GT, Dutton RA, Tran H, Zimmermann L, Sun D, Geaga JA, Simon TJ, Glahn DC, Cannon TD, Emanuel BS, Toga AW, Thompson PM. Mapping Cortical Thickness in Children with 22q11. 2 Deletions. Cereb.Cortex. 2006 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden CE, van Erp GT, Monterosso JR, Simon TJ, Glahn DC, Saleh PA, Hill NM, Donald-McGinn DM, Zackai E, Emanuel BS, Cannon TD. Regional brain abnormalities in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: association with cognitive abilities and behavioral symptoms. Neurocase. 2004;10:198–206. doi: 10.1080/13554790490495519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham PM, Zimmerman RA, Donald-McGinn D, Driscoll D, Emanuel BS, Zackai E. Enlarged Sylvian fissures in infants with interstitial deletion of chromosome 22q11. Am J Med.Genet. 1997;74:538–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bish JP, Pendyal A, Ding L, Ferrante H, Nguyen V, McDonald-McGinn D, Zackai E, Simon TJ. Specific cerebellar reductions in children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2006;399:245–248. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LE, Daly E, Toal F, Stevens A, Azuma R, Catani M, Ng V, van AT, Chitnis X, Cutter W, Murphy DG, Murphy KC. Brain and behaviour in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a volumetric and voxel-based morphometry MRI study. Brain. 2006;129:1218–1228. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelune GJ, Baer RA. Developmental norms for the Wisconsin Card Sorting test. J Clin.Exp.Neuropsychol. 1986;8:219–228. doi: 10.1080/01688638608401314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow EW, Mikulis DJ, Zipursky RB, Scutt LE, Weksberg R, Bassett AS. Qualitative MRI findings in adults with 22q11 deletion syndrome and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1436–1442. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00150-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow EW, Zipursky RB, Mikulis DJ, Bassett AS. Structural brain abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia and 22q11 deletion syndrome. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:208–215. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01246-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. Global attentional deviance as a marker of risk for schizophrenia: specificity and predictive validity. J Abnorm.Psychol. 1985;94:470–486. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.94.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debbane M, Schaer M, Farhoumand R, Glaser B, Eliez S. Hippocampal volume reduction in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2360–2365. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deboer T, Wu Z, Lee A, Simon TJ. Hippocampal volume reduction in children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome is associated with cognitive impairment. Behav.Brain Funct. 2007;3:54. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-3-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test-Second Edition (CVLT-II) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dufour F, Schaer M, Debbane M, Farhoumand R, Glaser B, Eliez S. Cingulate gyral reductions are related to low executive functioning and psychotic symptoms in 22q 11.2 deletion syndrome. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:2986–2992. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliez S, Barnea-Goraly N, Schmitt JE, Liu Y, Reiss AL. Increased basal ganglia volumes in velo-cardio-facial syndrome (deletion 22q11.2) Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:68–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliez S, Blasey CM, Schmitt EJ, White CD, Hu D, Reiss AL. Velocardiofacial syndrome: are structural changes in the temporal and mesial temporal regions related to schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:447–453. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliez S, Schmitt JE, White CD, Reiss AL. Children and adolescents with velocardiofacial syndrome: a volumetric MRI study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:409–415. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliez S, Schmitt JE, White CD, Wellis VG, Reiss AL. A quantitative MRI study of posterior fossa development in velocardiofacial syndrome. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:540–546. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Rock D, Roberts SA, Janal M, Kestenbaum C, Cornblatt B, Adamo UH, Gottesman II. Attention, memory, and motor skills as childhood predictors of schizophrenia-related psychoses: the New York High-Risk Project. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1416–1422. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser W, Nolan M, Bouras N. Mental Health in Mental Retardation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. Psychiatric disorders in mental retardation; pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes M, Solot C, Wang PP, Moss E, LaRossa D, Randall P, Goldmuntz E, Clark BJ, III, Driscoll DA, Jawad A, Emanuel BS, Donald-McGinn DM, Batshaw ML, Zackai EH. Cognitive and behavior profile of preschool children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion. Am J Med.Genet. 1999;85:127–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn DC, Laird AR, Ellison-Wright I, Thelen SM, Robinson JL, Lancaster JL, Bullmore E, Fox PT. Meta-Analysis of Gray Matter Anomalies in Schizophrenia: Application of Anatomic Likelihood Estimation and Network Analysis. Biol.Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding-Kushner KJ, Weller G, Shprintzen RJ. Velo-cardio-facial syndrome: language and psychological profiles. J Craniofac.Genet Dev.Biol. 1985;5:259–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS, Carroll BJ, Barrett JE. Psychopathology and the Brain. New York: Raven Press; 1991. Prefrontal cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia: The relevance of working memory; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Honea R, Crow TJ, Passingham D, Mackay CE. Regional deficits in brain volume in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Am.J.Psychiatry. 2005;162:2233–2245. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kates WR, Antshel K, Willhite R, Bessette BA, AbdulSabur N, Higgins AM. Gender-moderated dorsolateral prefrontal reductions in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome: implications for risk for schizophrenia. Child Neuropsychol. 2005;11:73–85. doi: 10.1080/09297040590911211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kates WR, Burnette CP, Bessette BA, Folley BS, Strunge L, Jabs EW, Pearlson GD. Frontal and caudate alterations in velocardiofacial syndrome (deletion at chromosome 22q11.2) J Child Neurol. 2004;19:337–342. doi: 10.1177/088307380401900506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kates WR, Burnette CP, Jabs EW, Rutberg J, Murphy AM, Grados M, Geraghty M, Kaufmann WE, Pearlson GD. Regional cortical white matter reductions in velocardiofacial syndrome: a volumetric MRI analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:677–684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kates WR, Miller AM, Abdulsabur N, Antshel KM, Conchelos J, Fremont W, Roizen N. Temporal lobe anatomy and psychiatric symptoms in velocardiofacial syndrome (22q11.2 deletion syndrome) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:587–595. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205704.33077.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy KM, Erickson KI, Rodrigue KM, Voss MW, Colcombe SJ, Kramer AF, Acker JD, Raz N. Age-related differences in regional brain volumes: A comparison of optimized voxel-based morphometry to manual volumetry. Neurobiol Aging. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern RS, Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Deng BH. NIMH-MATRICS survey on assessment of neurocognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr.Res. 2004;72:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Diwadkar VA, Montrose DM, Stanley JA, Pettegrew JW. Premorbid characterization in schizophrenia: the Pittsburgh High Risk Study. World Psychiatry. 2004;3:163–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine TR, Hullett C. Eta squared, partial eta squared, and misreporting of effect size in communication research. Human Communication Research. 2002;28:612–625. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski KE, Shashi V, Berry PM, Kwapil TR. Schizophrenic-like neurocognitive deficits in children and adolescents with 22q11 deletion syndrome. Am J Med.Genet B Neuropsychiatr.Genet. 2007;144:27–36. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1233–1239. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. J.Abnorm.Psychol. 2001;110:40–48. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitnick RJ, Bello JA, Shprintzen RJ. Brain anomalies in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am J Med. Genet. 1994;54:100–106. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320540204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss EM, Batshaw ML, Solot CB, Gerdes M, Donald-McGinn DM, Driscoll DA, Emanuel BS, Zackai EH, Wang PP. Psychoeducational profile of the 22q11.2 microdeletion: A complex pattern. J Pediatr. 1999;134:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KC, Jones LA, Owen MJ. High rates of schizophrenia in adults with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Arch.Gen.Psychiatry. 1999;56:940–945. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of, H. Computerized Diangostic Interview Schedule for Children. Rockville, MD: NIMH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, Wood SJ, Suckling J, Phillips LJ, Yung AR, Bullmore ET, Brewer W, Soulsby B, Desmond P, McGuire PK. Neuroanatomical abnormalities before and after onset of psychosis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI comparison. Lancet. 2003;361:281–288. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papolos DF, Faedda GL, Veit S, Goldberg R, Morrow B, Kucherlapati R, Shprintzen RJ. Bipolar spectrum disorders in patients diagnosed with velo-cardio-facial syndrome: does a hemizygous deletion of chromosome 22q11 result in bipolar affective disorder? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1541–1547. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.12.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulver AE, Nestadt G, Goldberg R, Shprintzen RJ, Lamacz M, Wolyniec PS, Morrow B, Karayiorgou M, Antonarakis SE, Housman D. Psychotic illness in patients diagnosed with velo-cardio-facial syndrome and their relatives. J Nerv.Ment.Dis. 1994;182:476–478. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199408000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajarethinam R, Sohi J, Arfken C, Keshavan MS. No difference in the prevalence of cavum septum pellucidum (CSP) between first-episode schizophrenia patients, offspring of schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Schizophr.Res. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport JL, Addington AM, Frangou S, Psych MR. The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2005. Mol.Psychiatry. 2005;10:434–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch N, Spoletini I, Wilke M, Bria P, Di PM, Di IF, Martinotti G, Caltagirone C, Spalletta G. Prefrontal-thalamic-cerebellar gray matter networks and executive functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr.Res. 2007;93:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaer M, Schmitt JE, Glaser B, Lazeyras F, Delavelle J, Eliez S. Abnormal patterns of cortical gyrification in velo-cardio-facial syndrome (deletion 22q11.2): an MRI study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;146:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 4):561–579. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashi V, Muddasani S, Santos CC, Berry MN, Kwapil TR, Lewandowski E, Keshavan MS. Abnormalities of the corpus callosum in nonpsychotic children with chromosome 22q11 deletion syndrome. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1399–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr.Res. 2001;49:1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shprintzen RJ. Velocardiofacial syndrome. Otolaryngol.Clin.North Am. 2000;33:1217–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70278-4. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shprintzen RJ, Goldberg R, Golding-Kushner KJ, Marion RW. Late-onset psychosis in the velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am J Med.Genet. 1992;42:141–142. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shprintzen RJ, Goldberg RB, Young D, Wolford L. The velo-cardio-facial syndrome: a clinical and genetic analysis. Pediatrics. 1981;67:167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon TJ, Ding L, Bish JP, Donald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, Gee J. Volumetric, connective, and morphologic changes in the brains of children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: an integrative study. Neuroimage. 2005;25:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugama S, Bingham PM, Wang PP, Moss EM, Kobayashi H, Eto Y. Morphometry of the head of the caudate nucleus in patients with velocardiofacial syndrome (del 22q11.2) Acta Paediatr. 2000;89:546–549. doi: 10.1080/080352500750027826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swillen A, Devriendt K, Legius E, Eyskens B, Dumoulin M, Gewillig M, Fryns JP. Intelligence and psychosocial adjustment in velocardiofacial syndrome: a study of 37 children and adolescents with VCFS. J Med.Genet. 1997;34:453–458. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.6.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, “Just the Facts”: what we know in 2008 part 1: overview. Schizophr.Res. 2008;100:4–19. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezenas Du MS, Mendizabai H, Ayme S, Levy A, Philip N. Prevalence of 22q11 microdeletion. J Med.Genet. 1996;33:719. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.8.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usiskin SI, Nicolson R, Krasnewich DM, Yan W, Lenane M, Wudarsky M, Hamburger SD, Rapoport JL. Velocardiofacial syndrome in childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Am Acad.Child Adolesc.Psychiatry. 1999;38:1536–1543. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Amelsvoort T, Daly E, Henry J, Robertson D, Ng V, Owen M, Murphy KC, Murphy DG. Brain anatomy in adults with velocardiofacial syndrome with and without schizophrenia: preliminary results of a structural magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch.Gen.Psychiatry. 2004;61:1085–1096. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Amelsvoort T, Daly E, Robertson D, Suckling J, Ng V, Critchley H, Owen MJ, Henry J, Murphy KC, Murphy DG. Structural brain abnormalities associated with deletion at chromosome 22q11: quantitative neuroimaging study of adults with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Br.J Psychiatry. 2001;178:412–419. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.5.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vataja R, Elomaa E. Midline brain anomalies and schizophrenia in people with CATCH 22 syndrome. Br.J Psychiatry. 1998;172:518–520. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.6.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vita A, De PL, Silenzi C, Dieci M. Brain morphology in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging studies. Schizophr.Res. 2006;82:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke M, Schmithorst VJ, Holland SK. Assessment of spatial normalization of whole-brain magnetic resonance images in children. Hum.Brain Mapp. 2002;17:48–60. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf RC, Hose A, Frasch K, Walter H, Vasic N. Volumetric abnormalities associated with cognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia. Eur.Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SJ, Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, Yucel M, Fornito A, McGorry PD. Progressive changes in the development toward schizophrenia: studies in subjects at increased symptomatic risk. Schizophr.Bull. 2008;34:322–329. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodin M, Wang PP, Aleman D, Donald-McGinn D, Zackai E, Moss E. Neuropsychological profile of children and adolescents with the 22q11.2 microdeletion. Genet Med. 2001;3:34–39. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yucel M, Wood SJ, Fornito A, Riffkin J, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Anterior cingulate dysfunction: implications for psychiatric disorders? J.Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003;28:350–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]