Abstract

Objective

To investigate the role of Junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A) in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis (SSc).

Methods

Biopsies from proximal and distal arm skin and serum were obtained from patients with SSc and normal (NL) volunteers. To determine the expression of JAM-A on SSc dermal fibroblasts and in SSc skin, cell surface ELISAs and immunohistology were performed. An ELISA was designed to determine the amount of soluble JAM-A (sJAM-A) in serum. Myeloid U937 cell-SSc dermal fibroblast and skin adhesion assays were performed to determine the role of JAM-A in myeloid cell adhesion.

Results

The stratum granulosum and dermal endothelial cells (ECs) from distal arm SSc skin exhibited significantly decreased expression of JAM-A compared to NL. However, sJAM-A was elevated in the serum of patients with SSc compared to NL. Conversely, JAM-A was increased on the surface of SSc compared to NL dermal fibroblasts. JAM-A accounted for a significant portion of U937 binding to SSc dermal fibroblasts. In addition, JAM-A contributed to U937 adhesion to both distal and proximal SSc skin.

Conclusions

JAM-A expression is dysregulated in SSc skin. Decreased expression of JAM-A on SSc ECs may result in a reduced response to proangiogenic basic fibroblast growth factor. While increased JAM-A expression on SSc fibroblasts may serve to retain myeloid cells, which in turn secrete angiogenic factors.

Keywords: Systemic sclerosis, Scleroderma, JAM-A, Cell adhesion

The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis (SSc) is complex and remains incompletely understood, however fibroblasts, monocytes, and endothelial cells (ECs) seem to be key players. These cells facilitate excessive synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins and deposition of increased amounts of collagen, immune activation, and vascular damage, all of which are known to be important in the development of this illness.[1]

Adhesion molecules play multiple roles in angiogenesis. Specific adhesion molecule expression can mediate angiogenesis indirectly by promoting the migration of monocytes.[2] These monocytes are then capable of becoming tissue macrophages and secreting angiogenic factors. Cellular adhesion molecules may have a role in the immunopathogenesis of SSc.[3] We and others have shown that several adhesion molecules are overexpressed in SSc skin.[4, 5] A number of soluble adhesion molecules are also elevated in SSc.[3]

JAM-A has been implicated in a variety of physiologic and pathologic processes involving cellular adhesion, tight junction assembly, and leukocyte transmigration.[6, 7] JAM-A facilitates leukocyte adhesion and transmigration through its interaction with lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1). Recently, JAM-A has been shown to play a role in angiogenesis.[8]

As SSc is characterized by both inflammatory cell infiltration and vasculopathy, we hypothesized that JAM-A may play a role in its pathogenesis. Here we demonstrate aberrant expression of JAM-A in SSc skin and sJAM-A in SSc serum. Moreover, we show a novel role for JAM-A in mediating myeloid cell adhesion to SSc skin.

Materials and methods

Patients and controls

Skin punch biopsies and peripheral blood samples were obtained from subjects with SSc (all with diffuse disease) and control subjects. All SSc patients fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology criteria for SSc and also met the criteria for diffuse SSc.[1, 9] Biopsies were taken with full informed consent, and this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Immunohistology

We performed immunohistologic staining on cryosections from SSc and normal skin, as described previously.[10] Goat anti-human JAM-A antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used as a primary antibody. The slides were read by a pathologist under blinded conditions. For JAM-A staining, the percentage of positive cells was calculated semi-quantitatively as stained cells in proportion to all cells of a distinctive subset. We also used a similar method with an anti-von Willebrand factor antibody to identify endothelial cells. Blood vessels were scored using a scale of: 0=avascular; 1=slight decrease; 2=normal; 3=slight increase; 4=marked increase.

Immunofluorescence

We performed immunofluorescence on cryosections from SSc and normal skin. Sections were fixed with 4% formalin and blocked with 20% fetal bovine serum and 5% donkey serum. Goat anti-human JAM-A antibody (R&D Systems) and mouse anti-human Von Willebrand factor (vWF) (Dako, Denmark) were used as primary antibodies. Fluorescent conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to stain cell nuclei. Images were taken at 400x.

Cell lysis and western blotting

NL and SSc dermal fibroblast cell lines were established as described previously.[11] Cell lysis and western blotting were performed as described.[10] Membranes were probed with anti-human JAM-A antibody (R&D Systems). Densitometric analysis of the bands was performed using UN-SCAN-IT software, version 5.1 (Silk Scientific).

Cell surface ELISA

Cell surface ELISAs were performed as previously described.[10] Dermal fibroblasts were plated in 96-well plates, stimulated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), or interleukin-1β (IL-1β), or interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (all 25 ng/ml, R&D Systems) or incubated in serum free RPMI for 24 hours. The fibroblasts were incubated with anti-human JAM-A antibody (R&D Systems) or goat IgG.

Human dermal microvascular endothelial cell (HMVEC) cell culture

HMVECs were obtained from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland) and cultured using EBM complete media (Lonza). The cells were serum starved overnight and then stimulated with either TNF-α or IL-1β. Supernatants were collected and concentrated using Amicon ultra filters (Millipore).

Serum JAM-A ELISA

Ninety six well microplates were coated with anti-human JAM-A antibody (R&D Systems) and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Sample or standards (R&D Systems) was added, followed by the addition of mouse anti-human JAM-A antibody (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-mouse biotinylated antibody (Vector Laboratories), streptavidin-HRP (R&D Systems), TMB substrate solution, and 2N H2SO4. The absorbance of each well read using a microplate reader at 450/570 nm. The diction limit of the sJAM-A ELISA was 0.3 ng/ml.

U937 cell-fibroblast adhesion assay

Adhesion assays were performed as previously described using myeloid U937 cells.[10] These cells are human histiocytic lymphoma cells that are myeloid. Combinations of JAM-A neutralizing antibody (Santa Cruz), mouse antibody to human CD11a (GeneTex Incorporated), neutralizing mouse anti-human ICAM-1 antibody (R&D Systems), or mouse IgG were used. The inhibitory effect of neutralizing antibody treatment was given as the percentage of maximal binding, which was defined as the number of adherent cells in the control antibody treated sections.

Stamper-Woodruff adhesion assay

In situ assays were performed as previously described.[10] JAM-A neutralizing antibody (R&D Systems) or goat IgG control were added to the skin sections. U937 cells were labeled with Calcein-AM fluorescent dye (5 μM, Invitrogen) and added to the sections and incubated for 1 hour in the dark. Non-adherent cells were washed off. The total number of fluorescence-labeled U937 cells was counted by a blinded observer using a fluorescence microscope. The inhibitory effect of the anti-JAM-A antibody was given as the percentage of maximal binding, which was defined as the number of adherent cells in the control antibody treated sections.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-tests were performed, and P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All values presented were the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Patient characteristics

The SSc group consisted of 18 females and 2 males (52.5 ± 1.8 years), while the NL control group consisted of 7 males and 3 females (51.2 ± 4.4 years). The mean disease duration of the SSc group was 3.7 ± 0.8 years. Punch biopsies were taken from clinically less involved proximal arm skin (mean skin score 1.2 ± 0.2) and involved distal forearm skin (2.0 ± 0.2). The proximal biopsy site was far away from the leading edge of the distal area.

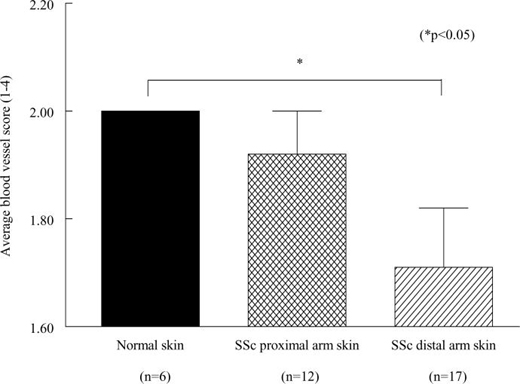

SSc distal arm skin had significantly fewer blood vessels compared to NL skin

Our work confirmed that in our patient population SSc distal arm skin has significantly fewer blood vessels (blood vessel score=1.7) compared to NL skin (blood vessel score=2.0, p<0.05) (figure 1).[12] In addition, we found that SSc proximal arm skin (blood vessel scale score=1.9) had a blood vessel score between that of SSc distal skin and NL skin.

Figure 1.

Distal SSc skin has fewer blood vessels than NL skin. n = the number of patients.

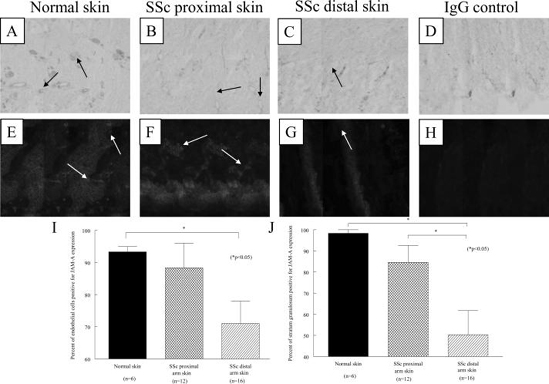

JAM-A is abnormally expressed in SSc skin

JAM-A expression in normal and SSc skin was evaluated using immunohistology and immunofluorescence. JAM-A is expressed on dermal ECs, fibroblasts, macrophages, and in the epidermis (figure 2). Moreover, dual immunofluorescence using anti-JAM-A and anti-vWF antibodies further indicated that JAM-A is expressed on dermal ECs. As shown in figure 2I, quantification of JAM-A immunohistology demonstrated that SSc dermal ECs exhibited significantly decreased expression of JAM-A (mean of 71%) compared to NL controls (mean of 93%, p<0.05). In addition, JAM-A was less expressed in the stratum granulosum of the epidermis of distal SSc skin (mean of 50%) compared to NL skin (mean of 98%, p<0.05, figure 2J). In contrast, SSc dermal perivascular macrophages expressed increased levels of JAM-A (12% in distal skin and 18% in proximal skin) compared to NL skin (mean of 4%, both p<0.05) (data not shown). Similarly, SSc subepidermal macrophages expressed increased levels of JAM-A (mean of 8% in distal skin and mean of 8% in proximal skin) compared to NL skin (mean of 3%, both p<0.05) (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Immunohistological and immunofluorescence analysis of JAM-A on NL and SSc skin. Representative photos of JAM-A immunohistological staining in endothelial cells of NL skin (A), proximal SSc skin (B), distal SSc skin (C), and of the isotype control (D) are shown, all at 200x. Arrows indicate positive JAM-A staining of vasculature. Representative photos of dual immunofluorescence staining of JAM-A (green) and vWF (red) in NL skin (E), proximal SSc skin (F), distal SSc skin (G), and of the isotype control (H) are shown, all at 400x. Arrows indicate dermal blood vessels. (I) Dermal ECs from proximal and distal SSc skin exhibited decreased expression of JAM-A compared to NL skin. (J) JAM-A was less expressed in the stratum granulosum of SSc skin compared to NL skin. n = the number of patients.

JAM-A was more highly expressed on SSc dermal fibroblasts vs. NL dermal fibroblasts

JAM-A was more highly expressed on dermal SSc compared to NL fibroblasts (figure 3A). Western blotting resulted in similar results (figure 3B). However, the expression of JAM-A on either SSc or NL dermal fibroblasts was not inducible by TNF-α, IFN-γ, or IL-1β (data not shown).

Figure 3.

JAM-A is overexpressed on SSc dermal fibroblasts. JAM-A is overexpressed on SSc dermal fibroblasts compared to NL dermal fibroblasts (Fig 3A). A representative western blot is shown in Fig 3B, expression of JAM-A protein is higher in SSc dermal fibroblasts. n = the number of different SSc patient or NL volunteer derived fibroblast cell lines.

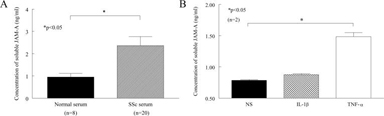

Elevated sJAM-A in SSc serum

A sJAM-A ELISA was designed, and serum JAM-A was detected in all normal volunteers and SSc patients. The concentration of sJAM-A in the serum of patients with SSc was 2.4 ± 0.4 ng/ml, whereas the concentration for NL controls was 1.0 ± 0.2 ng/ml (p<0.05) (figure 4A).

Figure 4.

sJAM-A is elevated in the serum of SSc patients and secreted by HMVECs. The concentration of sJAM-A in SSc serum was significantly greater compared to NL control serum (Fig 4A). n = the number of patients. sJAM-A is found in the culture supernatants of HMVECs (Fig 4B), and its expression is increased with stimulation by TNF-α. n = the number of replicates.

sJAM-A is secreted by ECs

sJAM-A was detectable in the culture supernatant of HMVECs (figure 4B). Moreover, stimulation with TNF-α resulted in a significant increase of sJAM-A in HMVEC culture supernatants (p<0.05).

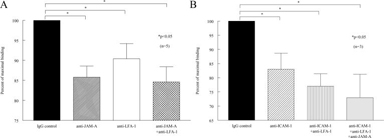

JAM-A mediates myeloid U937 cell binding to SSc dermal fibroblasts

We found that SSc dermal fibroblasts bound a greater number of myeloid U937 cells than NL dermal fibroblasts (p<0.05) (data not shown). Moreover, JAM-A accounted for a significant portion of U937 binding to SSc dermal fibroblasts. U937 binding to SSc dermal fibroblasts was inhibited by neutralizing anti-JAM-A antibody treatment (86% of maximal binding, p<0.05) (figure 5). Neutralizing antibody against the JAM-A ligand LFA-1 also inhibited U937 cell binding to SSc dermal fibroblasts (90% of maximal binding, p<0.05). Similarly, neutralizing antibody against the LFA-1 receptor ICAM-1 inhibited U937 cell binding to SSc dermal fibroblasts (83% of maximal binding). A combination of neutralizing antibodies against JAM-A, LFA-1, and ICAM-1 resulted in the greatest inhibition of U937 cell binding to SSc dermal fibroblasts (73% of maximal binding).

Figure 5.

JAM-A mediates adhesion of U937 cells to SSc dermal fibroblasts. U937 binding to SSc dermal fibroblasts was inhibited by anti-JAM-A antibody and anti-LFA-1 antibody (Fig 5A). U937 cell binding to SSc dermal fibroblasts was inhibited by anti-ICAM-1 antibody and a combination of anti-ICAM-1, LFA-1, and JAM-A antibodies. n = the number of different fibroblast cell lines from SSc patients.

JAM-A contributes to U937 cell adhesion to SSc skin

We found that similar to the results of the U937-fibroblast in vitro adhesion assay, anti-JAM-A neutralizing antibody decreased U937 cell binding to SSc skin (figure 6). U937 cell binding to SSc proximal arm skin (44% of maximal binding, p<0.05) and distal forearm skin (61% of maximal binding, p<0.05) was inhibited by anti-JAM-A antibody treatment. Collectively these results indicate that JAM-A plays an important role in myeloid cell adhesion to SSc skin.

Figure 6.

JAM-A mediates adhesion of U937 cells to SSc skin. (A), U937 binding to SSc proximal arm skin and distal arm skin sections was inhibited by anti-JAM-A antibody treatment. Representative photos of the effect of anti-JAM-A on U937 cell adhesion to proximal SSc skin (B), distal SSc skin (C), and in the presence IgG control in place of anti-JAM-A (D) are shown, all at 100x. n = the number of patients.

Discussion

The etiology and pathogenesis of SSc remains unknown. Nonetheless, signs of vascular injury and devascularization of involved organs in association with evidence of profound endothelial dysfunction are well documented. Adhesion molecules, molecules known to promote both inflammatory cell infiltration and angiogenesis, may play a role in the pathogenesis of SSc.[3]

Our results demonstrated that dermal ECs from SSc skin exhibit decreased expression of JAM-A compared to ECs in NL skin. Decreased JAM-A expression increases permeability. Blocking JAM-A expression caused a decrease in neutrophil and monocyte extravasation in several models including inflammatory meningitis, peritonitis, and ischemia-reperfusion injury.[13-16] These findings suggest that the downregulation of JAM-A expression on SSc dermal ECs may effect the influx of leukocytes into SSc skin.

In addition, JAM-A is a proangiogenic adhesion molecule. JAM-A forms a complex with integrin αvβ3 and mediates basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) induced angiogenesis.[8] JAM-A overexpression on ECs induces both EC proliferation and migration on vitronectin. In addition, inhibition of JAM-A signaling blocks bFGF-induced EC proliferation, tube formation and in vivo angiogenesis.[8, 17] Our results demonstrate that JAM-A is downregulated on SSc dermal ECs, and therefore may not be able to respond to bFGF and mediate angiogenesis.

Soluble adhesion molecules have also been shown to be elevated in patients with SSc. Recently, Cavusoglu et al. observed significantly higher levels of plasma sJAM-A in patients with advanced coronary artery disease and indicated that JAM-A may be an important mediator of the effects of inflammation on the vessel wall.[18] Our results show that the concentration of sJAM-A in the serum of patients with SSc is elevated compared to NL serum. Moreover, we demonstrated that sJAM-A can be secreted by cultured ECs. This is the first study to suggest a link between serum sJAM-A concentration and SSc, and further study is needed to determine if the concentration of serum sJAM-A correlates with additional clinical manifestations of SSc.

Previous studies have shown that SSc peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and SSc dermal fibroblasts are hyperadhesive.[19] Here we found that JAM-A is overexpressed on SSc dermal fibroblasts and mediates the adhesion of myeloid U937 cells to both SSc dermal fibroblasts and proximal and distal SSc skin. As myeloid cells mature into monocytes and macrophages that have the potential to secrete a variety of angiogenic factors, our results have particular importance to the pathogenesis of SSc.

Our study suggests that JAM-A plays multiple roles in the pathogenesis of SSc. The reduced expression of JAM-A on the surface of ECs may contribute to dysregulated angiogenesis in SSc skin, as JAM-A EC expression is required for bFGF induced angiogenesis.[8, 20, 21] Moreover, the elevated SSc serum levels of sJAM-A could be the result of the characteristic EC injury in SSc, further strengthening the suggestion of JAM-A as a vascular disease marker.[18] In contrast, JAM-A exemplifies the dual nature of an adhesion molecule, as our results demonstrate its importance in mediating myeloid cell retention in SSc skin. Collectively, these results suggest that JAM-A is dysregulated on multiple cell types in SSc, and that further study on its role in SSc skin angiogenesis is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by the NIH grants AI-40987 and AR-48267, the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, the Frederick G. L. Huetwell and William D. Robinson, MD, Professorship in Rheumatology, Scleroderma Research Foundation, NIH General Clinical Research Center grant M01-RR-00042, NIH Center for Translational Science Activities grant UL1-RR-024986, and by funding from the Scleroderma Center of the University of Michigan.

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

References

- [1].LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, Jablonska S, Krieg T, Medsger TA, Jr., et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kumar P, Hosaka S, Koch AE. Soluble E-selectin induces monocyte chemotaxis through Src family tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21039–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sato S. Abnormalities of adhesion molecules and chemokines in scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:503–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Abraham D, Lupoli S, McWhirter A, Plater-Zyberk C, Piela TH, Korn JH, et al. Expression and function of surface antigens on scleroderma fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1164–72. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Koch AE, Kronfeld-Harrington LB, Szekanecz Z, Cho MM, Haines GK, Harlow LA, et al. In situ expression of cytokines and cellular adhesion molecules in the skin of patients with systemic sclerosis. Their role in early and late disease. Pathobiology. 1993;61:239–46. doi: 10.1159/000163802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Liu Y, Nusrat A, Schnell FJ, Reaves TA, Walsh S, Pochet M, et al. Human junction adhesion molecule regulates tight junction resealing in epithelia. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2363–74. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.13.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ostermann G, Weber KS, Zernecke A, Schroder A, Weber C. JAM-1 is a ligand of the beta(2) integrin LFA-1 involved in transendothelial migration of leukocytes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:151–8. doi: 10.1038/ni755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Naik MU, Mousa SA, Parkos CA, Naik UP. Signaling through JAM-1 and alphavbeta3 is required for the angiogenic action of bFGF: dissociation of the JAM-1 and alphavbeta3 complex. Blood. 2003;102:2108–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Anonymous. Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic. Therapeutic Criteria Committee Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581–90. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rabquer BJ, Pakozdi A, Michel JE, Gujar BS, Haines GK, Imhof BA, et al. Junctional adhesion molecule-C mediates leukocyte adhesion to the rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Arthritis Rheum. doi: 10.1002/art.23867. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Louneva N, Huaman G, Fertala J, Jimenez SA. Inhibition of systemic sclerosis dermal fibroblast type I collagen production and gene expression by simvastatin. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1298–308. doi: 10.1002/art.21723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fleming JN, Schwartz SM. The pathology of scleroderma vascular disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34:41–55. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Corada M, Chimenti S, Cera MR, Vinci M, Salio M, Fiordaliso F, et al. Junctional adhesion molecule-A-deficient polymorphonuclear cells show reduced diapedesis in peritonitis and heart ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10634–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500147102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Del Maschio A, De Luigi A, Martin-Padura I, Brockhaus M, Bartfai T, Fruscella P, et al. Leukocyte recruitment in the cerebrospinal fluid of mice with experimental meningitis is inhibited by an antibody to junctional adhesion molecule (JAM) J Exp Med. 1999;190:1351–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.9.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Martin-Padura I, Lostaglio S, Schneemann M, Williams L, Romano M, Fruscella P, et al. Junctional adhesion molecule, a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that distributes at intercellular junctions and modulates monocyte transmigration. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:117–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Woodfin A, Reichel CA, Khandoga A, Corada M, Voisin MB, Scheiermann C, et al. JAM-A mediates neutrophil transmigration in a stimulus-specific manner in vivo: evidence for sequential roles for JAM-A and PECAM-1 in neutrophil transmigration. Blood. 2007;110:1848–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cooke VG, Naik MU, Naik UP. Fibroblast growth factor-2 failed to induce angiogenesis in junctional adhesion molecule-A-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2005–11. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000234923.79173.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cavusoglu E, Kornecki E, Sobocka MB, Babinska A, Ehrlich YH, Chopra V, et al. Association of plasma levels of F11 receptor/junctional adhesion molecule-A (F11R/JAM-A) with human atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1768–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rudnicka L, Majewski S, Blaszczyk M, Skiendzielewska A, Makiela B, Skopinska M, et al. Adhesion of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to vascular endothelium in patients with systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:771–5. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Naik MU, Naik UP. Junctional adhesion molecule-A-induced endothelial cell migration on vitronectin is integrin alpha v beta 3 specific. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:490–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Naik MU, Vuppalanchi D, Naik UP. Essential role of junctional adhesion molecule-1 in basic fibroblast growth factor-induced endothelial cell migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2165–71. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000093982.84451.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]