Abstract

Sphingolipid metabolites regulate cell proliferation, migration and stress responses. Alterations in sphingolipid metabolism have been proposed to contribute to carcinogenesis, cancer progression, and drug resistance. We identified a family of natural sphingolipids called sphingadienes and investigated their effects in colon cancer. We find that sphingadienes induce colon cancer cell death in vitro and prevent intestinal tumorigenesis in vivo. Sphingadienes exert their influence by blocking Akt translocation from the cytosol to the membrane, thereby inhibiting protein translation and promoting apoptosis and autophagy. Sphingadienes are orally available, slowly metabolized through the sphingolipid degradative pathway, and demonstrate limited short-term toxicity. Thus, sphingadienes represent a new class of therapeutic and/or chemopreventive agents that block Akt signaling in neoplastic and preneoplastic cells.

INTRODUCTION

Sphingolipids comprise a conserved family of lipids that contribute to the formation of membrane subdomains (lipid rafts) (1). Sphingolipids also give rise to bioactive metabolites such as sphingosine (So), ceramide (Cer) and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) that participate in signaling pathways regulating cellular proliferation, migration, survival, angiogenesis, and immune cell trafficking (2). Cer and So are generally growth-inhibitory and pro-apoptotic (3, 4), whereas S1P is a potent mitogen and angiogenic factor that promotes tumor progression (5, 6). A delicate balance exists between these metabolites in human cells, alterations of which may influence cell growth and the tumorigenic process.

Intestinal epithelial cells are exposed to sphingolipids by two separate routes: intracellular biosynthesis and uptake of ingested sphingolipids from the gut lumen. Dietary sphingolipids are metabolized by brush border enzymes in the gut epithelium (7) facilitating So or other sphingoid bases to be taken up by intestinal epithelial cells. Sphingolipids in soy and other natural sources exert cytotoxic effects on colonic epithelial cells (8-13). These effects may explain the observation that dietary sphingolipids suppress intestinal tumorigenesis in rodent models of colon cancer (9-13). Importantly, however, no in-depth studies elucidating the structural requirement of soy sphingolipids and/or the intracellular signaling events affected by soy sphingolipids necessary to block tumorigenesis have yet been reported.

Recently, we identified an unusual family of endogenous sphingoid bases containing conjugated trans double bonds at C4,5 and C6,7 in Drosophila melanogaster (14). These sphingadienes (SDs) are cytotoxic to insect cells and are structurally similar to SDs that comprise the sphingoid base backbone of soy sphingolipids. Complex sphingolipids containing SDs and sphingatrienes are found in aquatic plants used for medicinal purposes in traditional oriental medicine (15-17). Thus, we hypothesized that SDs might be the active component of soy that inhibits intestinal tumors. We report here that SDs are potent cytotoxic agents that act by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt pathway, one of the most frequently activated signaling pathways in cancer (18). SDs prevent Akt translocation and signaling, resulting in inhibition of protein translation and induction of apoptotic and autophagic cell death pathways. Our findings suggest that SDs may be active agents against colon cancer. Furthermore, by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt pathway downstream of PI3K itself, SDs could potentially expand the “PI3K inhibitor arsenal” against cancer, inflammation, and other pathological conditions in which the PI3K/Akt pathway plays a central role (19).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-Akt, anti 4EBP-1, anti-phospho-4EBP-1, anti-PARP and horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-phospho-Akt1/2/3 (Ser473) antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-actin antibody, MDC, 3-MA and IGF1 were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). D-erythro-C14-So and N-acetyl-D-erythro-C14-So (C2-Cer) were from Matreya (Pleasant Gap, PA). D-erythro-C17-So, D-erythro-C17-S1P, GluCer (soy) and 1-C16:0-2-lysoPC were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). AC-DEVD-pNA was from BioMol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with high glucose (DME H-21), FBS and antibiotics were from UCSF Tissue Culture Facility. Cell lines were transfected with FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Beclin siRNA was from Dharmacon, Inc. (Lafayette, CO).

Human cell culture and transfections

HT29, HCT116, SW480, and DLD1 cell lines were from ATCC (Rockville, MD) and grown in DME H-21 containing 10 % FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. SW480 cells were transiently transfected with recombinant human-Akt1 containing a hemagglutinin tag and the Src myristoylation (myr) sequence cloned into pcDNA3.0 (myr-Akt1) (20) from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). SW480 cells were transiently transfected with LC3-GFP, a construct encoding a microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3)-green fluorescence protein (GFP) fusion or pDest-mCherry-EGFP-LC3B plasmid DNA (21). In some experiments, cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3-myr-Akt1. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with a plasmid expressing a GFP-Akt1 pleckstrin homology domain (PHD) fusion or with the corresponding mutant GFP-Akt1-PHD (E17K) (a gift from James Thomas, Lilly) (22).

Cell viability and caspase 3 activity

Lipids and inhibitors were solubilized in ethanol or DMSO from 2.5 to 5 mM and diluted into fresh medium. Cells were grown in medium containg 10% FBS until 70-80% confluent and then treated with lipids. Viability of cells was determined by measuring their ability to hydrolyze the tetrazolium compound 3-(3,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-)4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) into formazan using the Cell Titer 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI). After addition of the MTS to the media, cells were incubated at 37°C and absorbance at 490 nm was determined. For apoptosis analysis, caspase lysis buffer containing 0.1% CHAPS was added to cell pellets, followed by three cycles of freeze-thaw and centrifugation of whole cell extracts. Apoptosis was then determined by quantitating caspase-3 activation in the supernatants as described (23).

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described (23). Signals were visualized using the SuperSignal West-Pico kit (Pierce, Rockford, Il) and quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software (NIH).

Autophagy

SW480 cells transfected with LC3-GFP or pDest-mCherry-EGFP-LC3B were treated with SD. Punctate formation was monitored by fluorescent microscopy. Pictures were taken at 3, 6 and 18 h post SD treatment. In some experiments, cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3-myr-Akt1, leading to expression of myristoylated Akt. For beclin downregulation studies, specific siRNA against beclin-1 (siGenome SMARTpool M-10552) was obtained from Dharmacon (Thermo Scientific). SW480 cells in 12 well plates (100,000 cells /well) were transfected with 40 pmol siRNA/well using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), as per the manufacture’s instructions.

(GFP)-Akt1 PHD fusion protein localization and microscopy

HeLa cells transiently transfected with Akt1-PHD green fluorescent protein fusion constructs were grown on slides for 24 h, treated with 1 μg/ml insulin or vehicle and incubated for 1 h, followed by visualization using fluorescence microscopy. Some cells were pre-treated with 10 μM SDs 6 h prior to insulin treatment.

Animals

For toxicity study, ten 10-12 week-old male C57BL/6 mice were administered by gavage 25 mg/kg SD in 0.5 % methylcellulose in sterile water, pH 5-6 (n = 7) or 0.5% methycellulose vehicle control (n = 3) for 10 days. Subjects were euthanized, phlebotomized and organs were harvested and fixed. For tumorigenicity study, 12-week-old ApcMin/+ male mice were administered by gavage either 25 mg/kg SD (n = 10) or vehicle (n = 10) for 10 days. Subjects were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. Grossly visible polyps were counted, measured (diameter), removed at the base, and frozen in LN2. The remaining intestinal tissues were prepared for histological examination.

Statistical analysis

Statisical analysis was performed using Student’s t test; values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

SDs inhibit the growth of colon cancer cells

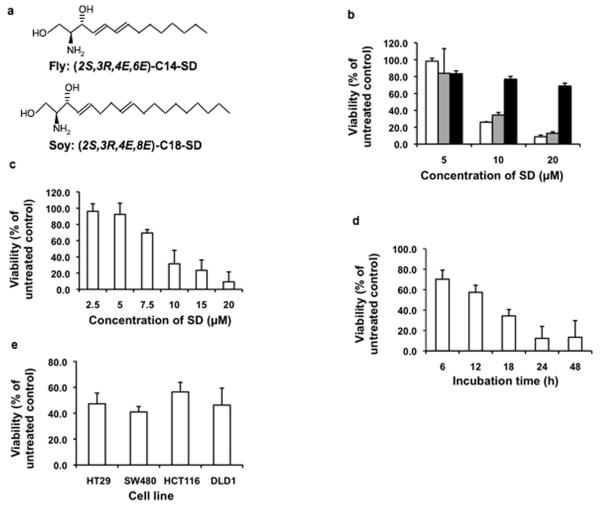

The natural isomers of fly SD [(2S,3R, 4E,6E)-2-amino-tetradecadiene-1,3-diol] and soy SD [(2S,3R, 4E,8E)-2-amino-octadecadiene-1,3-diol] (Figure 1a), hereafter referred to as C14 and C18 SDs, were compared to soy glucosylceramides (GluCer) containing a SD backbone for their effects on the viability of HT29 colon cancer cells. SDs derived from either source inhibited cell viability with similar potency, whereas soy GluCer was less effectual (Figure 1b). Subsequent experiments were performed with C14 SD unless stated otherwise, due to greater availability of this compound. As shown in Figures 1c and 1d, SDs inhibited cell viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The cytotoxic effect of SDs was also observed in other colon cancer cell lines (Figure 1e). In contrast, non-malignant human colon mucosal epithelial cells were less sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of SDs (data not shown).

Figure 1. SDs are cytotoxic to human colon cancer cells.

Drosophila SDs have a 14 carbon backbone containing conjugated double bonds at positions 4,5 and 6,7 [C14(4,6)SD]; soy SDs have an 18 carbon backbone with double bonds at positions 4,5 and 8,9 [C18(4,8)SD] (a). HT29 cells were incubated with C14(4,6)SD (white bars), C18(4,8)SD (gray bars), or soy GluCer (black bars). Viability was determined after 18 h by MTT assay (b). HT29 cells were incubated with C14(4,6)SD. Viability was determined after 18 h by MTT assay (c). HT29 cells were treated with 10 μM C14(4,6)SD. Viability was determined at indicated time points (d). Human colon cancer cell lines were treated with 10 μM C14(4,6)SD. Viability was determined after 18 h (e). Results are average values ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments.

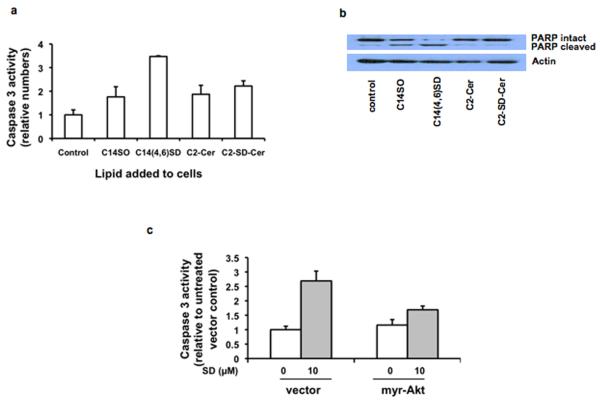

SDs induce conserved cell death pathways

To determine the mechanism of SD-mediated cytotoxicity, we incubated HT29 cells for 24 h with SDs and evaluated the effect of treatment on apoptosis. As shown in Figure 2a, SDs elicited a 3.5-fold increase in caspase-3 activity compared with vehicle-treated control cells. Apoptosis was confirmed by the presence of the cleaved form of PARP, as shown in Figure 2b. The presence of the second double bond conferred a two-fold increase in apoptosis when compared to a So molecule of comparable chain length. SD effects were compared to those of C2-Cer, a cell permeable ceramide analog and well-characterized inducer of apoptosis. C2-Cer containing a So backbone and C2-Cer containing a SD backbone (C2-SD-Cer) were comparable to So and less effective than SDs under identical conditions. To address whether intrinsic and/or extrinsic apoptotic pathways were involved, cells were pretreated with an inhibitor of caspase 8 to block the extrinsic pathway, an inhibitor of caspase 9 to block the intrinsic pathway, or a pan-caspase inhibitor to block both pathways. All three caspase inhibitors prevented PARP cleavage in response to SD treatment, indicating that both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways are induced by SDs (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2. SDs induce apoptosis in colon cancer cells.

HT29 cells were treated for 24 h with 10 μM C14-So, C14(4,6)SD, or C2-Cer containing a C14-sphingoid base. Apoptosis was evaluated by caspase 3 activity (a) and PARP cleavage (b). HT29 cells transfected with myr-Akt were incubated with 10 μM C14(4,6)SD for 24h. Caspase 3 activity was determined on whole cell extracts. For control vs. myr-AKT transfected cells, p = 0.0001 (c). Results are average values ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments.

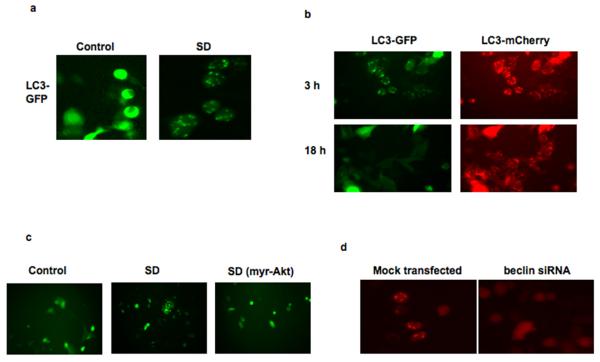

Treatment of the colon cancer cell line SW480 with SDs resulted in a different morphological picture, with formation of abundant cytoplasmic vacuoles as early as 2 h after SD administration (Supplementary Figures 2a and 2b). This observation prompted us to assess the effect of SDs on autophagy, since sphingolipids have been shown to play a role in this process (24). Autophagy is a process by which cells conserve energy during times of nutrient deprivation (25). During autophagy, cells recycle their biological material by forming autophagosomes, which are then delivered to the lysosome for degradation. The ability of SDs to induce autophagy was confirmed by the observation of a punctate fluorescence pattern after SD treatment of SW480 cells transiently transfected with a construct driving expression of an LC3-GFP fusion protein, a marker of early autophagosomes (Figure 3a). In contrast, vehicle-treated cells demonstrated a uniform fluorescence pattern, indicating the absence of autophagic vacuoles. To further confirm the presence of autophagic vacuoles and their delivery to lysosomes in response to SD treatment, SW480 cells were transiently transfected with the pDest-mCherry-EGFP-LC3B plasmid, which contains the LC3 protein tagged by both GFP and mCherry (21). In non-autophagic cells, the fusion protein displays a uniform cytoplasmic expression pattern; however, in cells undergoing early stages of autophagy, both GFP and mCherry fluorescence are present in punctate fashion, which represent localization to early autophagosomes. Over time, autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes whose acidic environment leads to quenching of GFP fluorescence, but not that of mCherry. As shown in Figure 3b, treatment of SW480 cells with SDs induced autophagosome formation by 3 h. Autophagosome fusion with lysosomes occurred within the next 18 h, as indicated by progressive loss of GFP signal. Further, SW480 cells were incubated with SDs and stained with the compound monodansylcadaverine (MDC), a specific in vivo marker for autophagosomes. As shown in Supplementary Figures 2c, the vacuoles formed after SD treatment are stained with MDC. Pretreatment of SW480 cells with 3-MA, an inhibitor of autophagosome formation, prevented the formation of stained vacuoles after SD treatment. During autophagy endogenous LC3-I is converted to its phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated form LC3-II. SD treatment of SW480 cells induced conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II (Supplementary Figures 3a and 3b). To further explore SD-induced autophagy, we examined its dependence on beclin-1, the mammalian orthologue of the yeast Apg6/Vps30 gene and a critical component of autophagic pathways. Downregulation of beclin-1 was accomplished by siRNA, as shown in Supplementary Figure 4. Whereas 10 μM C18 SD treatment for 24h reduced the viability of mock transfected SW480 cells to 66.7 ± 13% of vehicle treated controls, SW480 cells lacking beclin-1 maintained 95 ± 9% viability after SD treatment. In addition, autophagosome formation was reduced in SW480 cells downregulated for beclin-1, using pDest-mCherry-EGFP-LC3B as a marker of autophagy (Figure 3d). These results confirm that SD treatment induces beclin-dependent autophagy.

Figure 3. SDs induce autophagy in colon cancer cells.

SW480 cells were transfected with LC3-GFP. In control cells, LC3-GFP reveals a uniform expression pattern. Treatment with 5 μM C14(4,6)SD for 6 h stimulates autophagy, and LC3-GFP appears punctate (a). SW480 cells were co-transfected with mCherry-EGFP-LC3B and LC3-GFP. Cells were treated with 5 μM C14(4,6)SD. After 3 h, both markers demonstrate an overlapping punctate expression pattern, indicating localization to early autophagosomes. After 18 h, only LCB3-mCherry shows a punctate expression pattern indicative of autophagolysosomes (b). SW480 cells containing LC3-GFP were transfected with vector or myr-Akt. Cells were treated with 5 μM C14(4,6)SD. After 6h, vector-containing cells exhibited autophagy (380 vesicles per 100 cells), whereas autophagy was almost completely inhibited by myr-Akt (80 vesicles per 100 cells). In control cells without C14(4,6)SD treatment the number of vesicles observed was 25 per 100 cells (c). SW480 cells were either mock transfected or transfected with beclin-1 siRNA, followed by transient transfection with mCherry-EGFP-LC3B. After treatment with 10 μM C18(4,8)SD the progression of autophagy was followed by fluorescent microscopy, and cells were photographed at 6h (d).

SDs induce cell death through an Akt-dependent mechanism

Apoptosis and autophagy are both under repressive control by the PI3K/Akt pathway, which is constitutively activated in many cancer cells. To explore the role of the PI3K/Akt pathway in SD-mediated cytotoxicity, the effect of SDs was tested on cells expressing a myristoylated, constitutively active form of Akt (myr-Akt) in comparison to cells transfected with empty plasmid. As shown in Supplementary Figures 3a and 3b, expression of myr-Akt in SW480 cells attenuated SD-mediated conversion of endogenous LC3-I to LC3-II, indicating that autophagy was inhibited. However, at high doses of SD, some conversion was evident. Therefore, to confirm the role of Akt in SD-mediated autophagy, SW480 cells co-expressing LC3-GFP plus myr-Akt or LC3-GFP plus plasmid control were analyzed after SD treatment. Figure 3c demonstrates the induction of autophagy by SDs was almost completely inhibited by constitutive Akt activation, as shown by lack of autophagosome formation. Constitutive activation of Akt also abrogated SD-mediated apoptosis in HT29 cells (Figure 2c). Thus, SDs induce apoptotic and autophagic cell death programs through an Akt-dependent mechanism.

SDs inhibit Akt translocation, activation, and signaling in colon cancer cells

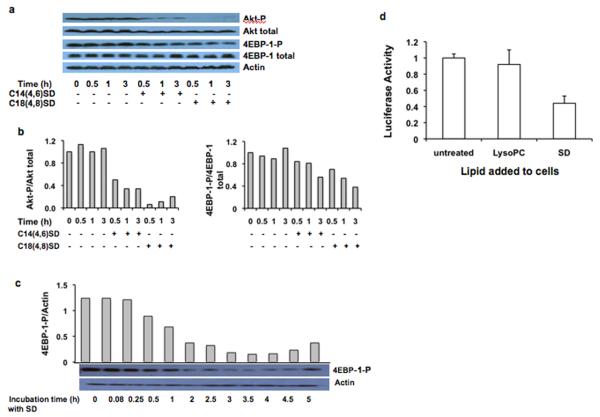

To investigate the effect of SDs on Akt signaling, we treated HT29 cells with SDs for various time periods and analyzed expression of total and phosphorylated Akt by immunoblotting of whole cell extracts. Figures 4a and 4b show that SDs inhibit Akt activation. The effect was apparent from 30 min to 3 h of incubation.

Figure 4. Akt and 4EBP-1 phosphorylation are inhibited by SDs in colon cancer cells.

HT29 cells were incubated with 10 μM SDs for the indicated times. Cells were harvested, and protein levels were evaluated by western blotting (a). Actin is the loading control. The ratios of phosphorylated Akt to total Akt and phosphorylated 4EBP-1 to total 4EBP-1 were quantified by densitometry (b). SW480 cells were incubated with 10 μM C14(4,6)SD for the indicated times. Actin and phosphorylated 4EBP-1 were evaluated by western blotting and quantified by densitometry (c). HT29 cells were incubated for 6 h with 10 μM C14(4,6)SD, harvested, and homogenized in lysis buffer, and subjected to centrifugation at 30,000 × g. Supernatants were recovered and their translational activity was measured with the Dual Design Luciferase Reporter Assay System (d). Results are average values ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments.

One of the major functions of Akt is the regulation of protein synthesis (26). Akt activation results in mTOR-catalyzed phosphorylation of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP-1), an inhibitor of protein translation, promoting its release from translational initiation factor eIF4E and thereby stimulating cap-dependent mRNA translation (26). Treatment of HT29 cells with SDs reduced cellular phosphorylated 4EBP-1 compared to total 4EBP-1 (Figures 4a and 4b). The inhibition of 4EBP-1 phosphorylation was evident as early as 1 h after treatment, and by 3 h 4EBP-1 phosphorylation was reduced to less than 60% of control cells. In SW480 cells treated with C14 SD, 4EBP-1 phosphorylation was reduced to 50% after 1 h and to 20% in 3 h (Figure 4c). Taken together, our results demonstrate that SDs attenuate Akt activation and signaling. SD-mediated inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway and downstream effects on 4EBP-1 would be predicted to inhibit protein translation. To verify this possibility, a cell-free translation assay was devised in which HT29 cells treated with SDs or vehicle were disrupted, and whole cell extracts were evaluated for their ability to translate an mRNA template encoding firefly luciferase into active enzyme. To avoid effects that could potentially be caused by inhibition of amino acid uptake, amino acids were provided in excess in the translation assay. Figure 4d demonstrates that pretreatment of HT29 cells with SDs inhibits protein translation compared with cells treated with lysophosphatidylcholine or vehicle. In contrast to the observed effects on apoptosis, autophagy and protein translation, SD treatment did not alter the cell cycle profile of HT29 or SW480 cells (Supplementary Figure 5).

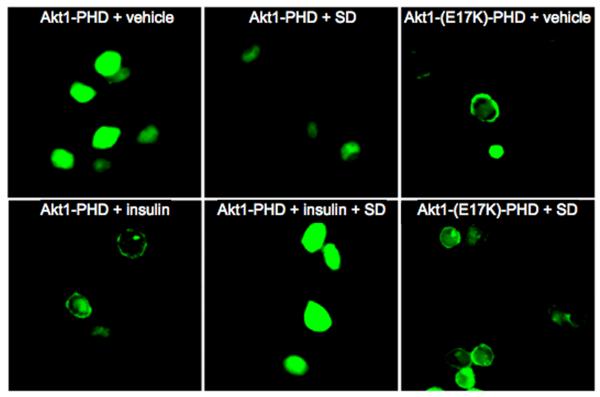

The PHD of Akt proteins is lipophilic and capable of interacting with phosphatidylinositol-tris-3,4,5-phosphate (PIP3), thereby recruiting Akt to the membrane in response to PI3K activation (27). Subsequent to membrane localization, Akt is activated by phosphorylation. We examined the effect of SDs on subcellular localization in HeLa cells of a fusion protein consisting of GFP and the PHD of Akt1 (Akt1-PHD) (22). Similar experiments were conducted in cells expressing a PHD mutant containing a single amino acid substitution in the PHD (Akt1-E17K-PHD) that facilitates interaction with phosphoinositide ligand, leading to pathological membrane localization, constitutive Akt activation, and cellular transformation (22). As shown in Figure 5, Akt1-PHD localized primarily to the cytoplasm of vehicle-treated control cells. As expected, treatment with insulin induced the translocation of Akt1-PHD to the membrane. However, pre-treatment with SDs prevented Akt1-PHD translocation in response to insulin treatment. These findings indicate that SDs inhibit Akt translocation by preventing interactions between the PHD and PIP3 that are required for its recruitment to the membrane. In contrast, the subcellular localization of a constitutively membrane-bound mutant Akt1-E17K-PHD was unaffected by SDs, consistent with our finding that cells with constitutively active Akt are able to resist SD-mediated cytotoxicity. These results were further substantiated by subcellular fractionation studies demonstrating that SD treatment of HT29 cells reduces membrane-bound, activated Akt but has no effect on constitutively membrane-bound Akt (Supplementary Figure 6).

Figure 5. Akt translocation and phosphorylation are blocked by SDs.

HeLa cells were transfected with an Akt1-PHD GFP fusion construct (Akt1-PHD) or an Akt1 E17K-PHD GFP fusion harboring the E to K mutation in the PHD that constitutively localizes it to the membrane (Akt1-E17K-PHD). After 48 h incubation, cells were pretreated with 10 μM C14(4,6)SD (SD) or vehicle for 3 h, followed by insulin treatment. Quantitative analysis showed that insulin treatment resulted in a translocation of Akt to the membrane in more than 60 % of the cells analysed. Pretreatment with SD reduced the effect of insulin significantly and membrane localized Akt was observed in less than 20 % of the cells.

SDs could inhibit Akt translocation by reducing the amount of PIP3 lipid formed in response to insulin stimulation. To address this possibility, phosphatidylinositols in SW480 cells were labeled by incorporation of radioactive phosphate. Cells were then treated with SDs and evaluated for effects of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) administration on the formation of PIP3. In control cells, treatment with IGF1 resulted in a twofold increase in the ratio of PIP3/PIP (Supplementary Figure 7). A similar effect of IGF1 administration was observed in SD treated cells. These findings indicate that under the experimental conditions used, SD treatment does not affect PIP3 formation.

SDs suppress intestinal tumorigenicity in vivo

Based on our in vitro findings, we hypothesized that SDs would reduce intestinal tumorigenicity. To test this hypothesis, we assessed the influence of SDs on the disease course of ApcMin/+ mice, a well-characterized rodent model of intestinal tumorigenesis (28). ApcMin/+ mice develop intestinal polyps that rarely progress to frank carcinoma and have been used to demonstrate the chemopreventive effects of many natural compounds, including sphingolipids (12). Further, ApcMin/+ polyps exhibit upregulated Akt signaling, in addition to activation of Wnt signaling (29).

A limited toxicity study was undertaken to establish the safety of delivering natural SDs orally to mice. C57BL/6 mice were administered 25 mg/kg C14 or C18 SDs in 0.5% methylcellulose by gavage for 10 days. Other than a grossly evident reduction in hematochezia, SDs produced no appreciable effects on mouse health parameters including body weight, hydration status, and activity. Blood chemistries, liver functions, and hematological parameters were not different in the treated and untreated groups (Supplementary Table 1). Further, no gross or microscopic pathology was noted in major solid organs of SD-treated animals. These results are consistent with in vitro finding that SDs are effectively metabolized by enzymes of the sphingolipid degradative pathway but at a slower rate than sphingosine (Supplementary Figures 8a and 8b).

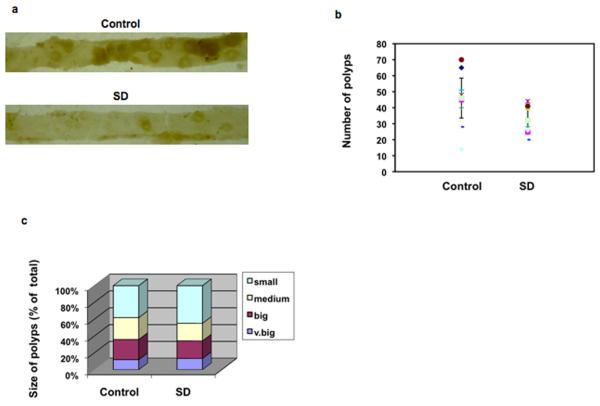

ApcMin/+ male mice were given food and water ad libidum, and beginning at 80 days of life either 25 mg/kg body weight of C14 SDs or vehicle (n = 10 per group) was administered daily by oral gavage. After 10 days, mice were euthanized, and gross polyps were sized and counted. As shown in Figures 6a and 6b, SD treatment was associated with a 35% reduction in polyp number compared with control mice. The average polyp numbers in all size categories were reduced in SD-treated animals, although the amount of reduction reached statistical significance only in the 1-2 and 2-3 mm categories. As shown in Figure 6c, a trend toward smaller polyps was observed in the SD-treated group compared with the vehicle-treated group. With regard to the number of polyps ≥ 1mm to those < 1 mm in diameter, a ratio of 1.6 was determined in the vehicle-treated subjects, compared to 1.2 in the SD-treated subjects. These findings confirm that oral delivery of SDs reduce polyp number and size in a mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis.

Figure 6. SDs inhibit intestinal tumorigenesis.

ApcMin/+ mice were administered 25 mg/kg body weight C14(4,6)SD or vehicle (n=10 per group). Mice were euthanized and intestinal tissues harvested on day 10. Gross polyps were counted and measured (diameter). Control and treated intestinal mucosa (a); Mean polyp number. For treated vs. control mice, p = 0.016 (b); Mean polyp size (diameter). Small = < 1mm; medium = 1-2 mm; big = 2-3 mm; very big = > 3 mm (c).

DISCUSSION

We have observed that the SD family of natural sphingolipids is cytotoxic to colon cancer. In contrast, GluCer compounds derived from soy were less efficient in affecting the growth of colon cancer cells in vitro, which suggests they must be metabolized to SDs by brush border enzymes of the gut before acquiring cytotoxic and tumor-preventive properties.

Sphingolipids influence the activity of various cellular targets involved in the regulation of cell survival, proliferation, and apoptosis (30). Our findings suggest that SDs act by inhibiting Akt signaling. It was shown previously that the unnatural Cer analog C2-Cer regulates insulin action in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes by interfering with the translocation of Akt to the membrane (31). SDs appear to act in a similar fashion in colon cancer cells but with greater potency than C2-Cer. The immediate downstream consequences of SD-mediated Akt inhibition include a block in protein translation and induction of autophagy. If the SD treatment is sustained, the colon cancer cells may undergo cell death by autophagy or concurrently with apoptosis. Which of these outcomes predominates in a particular cell type is presumably dictated by cellular context.

Mutations in the PI3K/Akt pathway including activating mutations in PI3K and loss-of-function mutations in the phosphatase PTEN (a negative regulator of PI3K signaling which is produced by a tumor suppressor gene) are commonly found in human malignancies (32). More rarely, activating mutations in Akt have been detected in cancer (22). Activation of this pathway enhances the biosynthesis of macromolecules needed to sustain the growth of rapidly proliferating cells and also blocks apoptotic pathways normally induced in response to stressful conditions, such as the harsh environment of a tumor. The effects of SDs on Akt translocation should counteract mutations conferring constitutive activation of PI3K, such as those identified in many colon cancer cells. Our finding that SDs are cytotoxic to HCT116, DLD1, and SW480 cells harboring such mutations supports this notion (33, 34).

We have demonstrated that SDs protect against intestinal tumorigenicity in a mouse model of intestinal polyposis. This suggests that increasing the oral intake of natural SDs from soy products may provide protection against colon cancer in humans, and that direct delivery of SDs may be useful in colon cancer treatment. However, studies that specifically address the efficacy of sphingadienes in preventing colonic tumors are needed to confirm this. Studies conducted over longer time periods will be required to fully characterize the toxicity profiles of natural sphingolipids. Since we have shown previously that S1P lyase and other genes in the sphingolipid degradative pathway are downregulated in intestinal polyps of the ApcMin/+ mouse and in human colon cancers, we suspect that intestinal neoplastic tissue may be more sensitive to SDs than surrounding uninvolved tissues (23). This is supported by in vitro studies demonstrating that S1P lyase-downregulation confers greater sensitivity to SDs (Supplemental Figure 9).

Sphingolipids found in meat and milk are metabolized to So, which is also cytotoxic to colon cancer cells. However, So is less potent than SD, consistent with previous reports demonstrating the importance of the second double bond in Cer potency (35). In addition, So is rapidly metabolized to S1P, and this conversion contributes to the enlargement and progression of intestinal polyps (36). S1P acts through a family of G protein coupled receptors to promote angiogenesis and block apoptotic pathways (37). S1P activation of its receptors leads to stimulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway (38-40). The major sphingosine kinase gene SPHK1 functions as an oncogene and is upregulated in colon cancer; administration of S1P-specific antibodies slows tumor progression and angiogenesis in murine models of cancer (41, 42). Thus, one major concern in the development of strategies to employ sphingolipids for chemotherapeutic purposes is the potential conversion of endogenous So or sphingolipid analogs to the corresponding phosphorylated sphingoid base. This conversion would create a self-limiting effect and could even have counterproductive effects on cell growth and tumor progression. In this regard, SDs demonstrate a distinct advantage over other sphingolipids, as they appear to be poorly converted to SD-phosphates, have a long half-life in intestinal epithelial cells, and the toxicity profile associated with short-term oral delivery of SDs is favorable.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants RAT005336A, CA129438, CA77528 and GM66954 (JDS), and HL-083187 (RB).

Nonstandard abbreviations used

- Cer

ceramide

- 4EBP-1

eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1

- IGF1

insulin like growth factor 1

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3

- L C B

long-chain bases

- LCBP

long chain base phosphates

- lysoPC

lysophosphatidylcholine

- 3-MA

3-methyladenine

- MDC

monodansylcadaverine (N-(5-Aminopentyl)-5-dimethylaminonaphtalene-1-sulfonamide)

- MTS

3-(3,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-)4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium

- myr-Akt

myristoylated-Akt

- PHD

pleckstrin homology domain

- PIP

phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositolbis-3,4-phosphate

- PIP3

phosphatidylinositol-tris-3,4,5-phosphate

- SD

sphingadiene

- So

sphingosine (sphingenine)

- S1P

sphingosine 1-phosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Degroote S, Wolthoorn J, van Meer G. The cell biology of glycosphingolipids. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:375–87. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim RH, Takabe K, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Export and functions of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Ceramide: an intracellular signal for apoptosis. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:73–7. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merrill A. Cell regulation by sphingosine and more complex sphingolipids. J Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 1991;23:83–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00768840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olivera A, Spiegel S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate as second messenger in cell proliferation induced by PDGF and FCS mitogens. Nature. 1993;365:557–9. doi: 10.1038/365557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Wada R, Yamashita T, et al. Edg-1, the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is essential for vascular maturation. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:951–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI10905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsson A, Duan RD. Absorption and lipoprotein transport of sphingomyelin. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:154–71. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500357-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweeney EA, Sakakura C, Shirahama T, et al. Sphingosine and its methylated derivative N,N-dimethylsphingosine (DMS) induce apoptosis in a variety of human cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 1996;66:358–66. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960503)66:3<358::AID-IJC16>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berra B, Colombo I, Sottocornola E, Giacosa A. Dietary sphingolipids in colorectal cancer prevention. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2002;11:193–7. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200204000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmelz EM, Dillehay DL, Webb SK, Reiter A, Adams J, Merrill AH., Jr. Sphingomyelin consumption suppresses aberrant colonic crypt foci and increases the proportion of adenomas versus adenocarcinomas in CF1 mice treated with 1,2-dimethylhydrazine: implications for dietary sphingolipids and colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4936–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemonnier LA, Dillehay DL, Vespremi MJ, Abrams J, Brody E, Schmelz EM. Sphingomyelin in the suppression of colon tumors: prevention versus intervention. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;419:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmelz EM, Roberts PC, Kustin EM, et al. Modulation of intracellular beta-catenin localization and intestinal tumorigenesis in vivo and in vitro by sphingolipids. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6723–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Symolon H, Schmelz E, Dillehay D, Merrill AJ. Dietary soy sphingolipids suppress tumorigenesis and gene expression in 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-treated CF1 mice and ApcMin/+ mice. J Nutr. 2004;134:1157–61. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.5.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fyrst H, Zhang X, Herr D, et al. Identification and characterization by electrospray mass spectrometry of endogenous Drosophila sphingadienes. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:597–606. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700414-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Row L, Ho J, Chen C. Cerebrosides and tocopherol trimers from the seeds of Euryale ferox. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1214–7. doi: 10.1021/np070095j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugawara T, Zaima N, Yamamoto A, Sakai S, Noguchi R, Hirata T. Isolation of sphingoid bases of sea cucumber cerebrosides and their cytotoxicity against human colon cancer cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:2906–12. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan J, Dong Z, Liu J. New cerebrosides from the basidiomycete Cortinarius tenuipes. Lipids. 2003;38:81–4. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crabbe T, Welham M, Ward S. The PI3K inhibitor arsenal: choose your weapon! Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:450–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Vazquez F, et al. Regulation of G1 progression by the PTEN tumor suppressor protein is linked to inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2110–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpten JD, Faber AL, Horn C, et al. A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in cancer. Nature. 2007;448:439–44. doi: 10.1038/nature05933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oskouian B, Sooriyakumaran P, Borowsky A, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase potentiates apoptosis via p53- and p38-dependent pathways and is downregulated in colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17384–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng W, Kollmeyer J, Symolon H, et al. Ceramides and other bioactive sphingolipid backbones in health and disease: lipidomic analysis, metabolism and roles in membrane structure, dynamics, signaling and autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1864–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruggero D, Sonenberg N. The Akt of translational control. Oncogene. 2005;24:7426–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodgett JR. Recent advances in the protein kinase B signaling pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:150–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dove WF, Cormier RT, Gould KA, et al. The intestinal epithelium and its neoplasms: genetic, cellular and tissue interactions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;353:915–23. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moran A, Hunt D, Javid S, Redston M, Carothers A, Bertagnolli M. Apc deficiency is associated with increased Egfr activity in the intestinal enterocytes and adenomas of C57BL/6J-Min/+ mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43261–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404276200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lahiri S, Futerman A. The metabolism and function of sphingolipids and glycosphingolipids. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2270–84. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7076-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salinas M, Lopez-Valdaliso R, Martin D, Alvarez A, Cuadrado A. Inhibition of PKB/Akt1 by C2-ceramide involves activation of ceramide-activated protein phosphatase in PC12 cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;15:156–69. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samuels Y, Diaz J, LA, Schmidt-Kittler O, et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. 2005;7:561–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrow C, Gray A, Dive C. Comparison of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signalling within a panel of human colorectal cancer cell lines with mutant or wild-type PIK3CA. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Struckhoff AP, Bittman R, Burow ME, et al. Novel ceramide analogs as potential chemotherapeutic agents in breast cancer. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:523–32. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.062760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohno M, Momoi M, Oo M, et al. Intracellular role for sphingosine kinase 1 in intestinal adenoma cell proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7211–23. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02341-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hla T, Lee MJ, Ancellin N, Paik JH, Kluk MJ. Lysophospholipids-receptor revelations. Science. 2001;294:1875–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1065323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baudhuin LM, Jiang Y, Zaslavsky A, Ishii I, Chun J, Xu Y. S1P3-mediated Akt activation and cross-talk with platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) Faseb J. 2004;18:341–3. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0302fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morales-Ruiz M, Lee M, Zollner S, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate activates Akt, nitric oxide production, and chemotaxis through a Gi protein/phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19672–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Means C, Xiao C, Li Z, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate S1P2 and S1P3 receptor-mediated Akt activation protects against in vivo myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2944–51. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01331.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xia P, Gamble JR, Wang L, et al. An oncogenic role of sphingosine kinase. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1527–30. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00834-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Visentin B, Vekich J, Sibbald B, et al. Validation of an anti-sphingosine-1-phosphate antibody as a potential therapeutic in reducing growth, invasion, and angiogenesis in multiple tumor lineages. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:225–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.