Abstract

Human keratinocytes (KCs) express multiple EGF receptor (EGFR) ligands; however, their functions in specific cellular contexts remain largely undefined. To address this issue, first we measured mRNA and protein levels for multiple EGFR ligands in KCs and skin. Amphiregulin (AREG) was by far the most abundant EGFR ligand in cultured KCs, with > 19 times more mRNA and > 7.5 times more shed protein than any other family member. EGFR ligand expression in normal skin was low (< 8 ‰ of RPLP0/36B4); however, HB-EGF and AREG mRNAs were strongly induced in human skin organ culture. KC migration in scratch wound assays was highly metalloproteinase (MP)- and EGFR dependent, and markedly inhibited by EGFR ligand antibodies. However, lentivirus-mediated expression of soluble HB-EGF, but not soluble AREG, strongly enhanced KC migration, even in the presence of MP inhibitors. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-induced ERK phosphorylation was also strongly EGFR and MP dependent and markedly inhibited by neutralization of HB-EGF. In contrast, autocrine KC proliferation and ERK phosphorylation were selectively blocked by neutralization of AREG. These data show that distinct EGFR ligands stimulate KC behavior in different cellular contexts, and in a MP-dependent fashion.

Keywords: epidermal growth factor receptor, amphiregulin, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor, wound healing, signal transduction

Introduction

Substantial evidence implicates EGF-like growth factor activity in the regulation of cell migration, proliferation, survival and differentiation of normal and malignant epithelial cells (Hashimoto et al., 1994; Piepkorn et al., 1998; Yarden and Sliwkowski, 2001). Human KCs express multiple EGF-like growth factors including amphiregulin (AREG), betacellulin (BTC), epiregulin (EREG), heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF), and TGF-α in an autocrine fashion (Barnard et al., 1994; Coffey et al., 1987; Hashimoto et al., 1994; Piepkorn et al., 1998; Shirakata et al., 2000). All EGFR ligands are synthesized as membrane-bound precursors that require MP-mediated proteolytic cleavage to produce the soluble, mature forms (for review see (Sanderson et al., 2006)). Although paracrine/juxtacrine signaling by transmembrane precursors has been shown to mediate biological effects in some experimental systems (Iwamoto and Mekada, 2000; Miyoshi et al., 1997; Singh et al., 2004; Willmarth and Ethier, 2006), findings from numerous studies strongly suggest that major EGF-like growth factor functions including cell proliferation depend on proteolytic release of soluble EGFR ligands from their membrane-bound precursors (Peschon et al., 1998; Sanderson et al., 2006; Yamazaki et al., 2003).

EGF-like growth factors bind to one or more members of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases, which includes the EGF receptor (EGFR), also known as ErbB1 or HER1, ErbB2 (HER2 or neu), ErbB3 (HER3), and ErbB4 (HER4) (Sanderson et al., 2006). Ligand binding results in conformational changes of the extracellular receptor domains (Burgess et al., 2003) initiating signaling mechanisms that regulate multiple cellular responses such as migration, proliferation, differentiation and survival (Citri and Yarden, 2006; Yarden and Sliwkowski, 2001).

Human KCs express substantial levels of EGFR, ErbB2, and ErbB3 but no detectable ErbB4 protein (De Potter et al., 2001; Press et al., 1990; Prigent et al., 1992; Stoll et al., 2001) suggesting that EGF-like growth factor signaling in KCs proceeds through the formation of EGFR homo- or EGFR/ErbB2 and/or EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers.

Although the function of EGFR ligands in human KCs appears to be highly redundant (Barnard et al., 1994; Coffey et al., 1987; Cook et al., 1991; Hashimoto et al., 1994; Shirakata et al., 2000; Strachan et al., 2001), the importance of individual growth factors in specific cellular contexts has not been elucidated. From animal models and other experimental systems it is known that EGF-like growth factors have distinct roles in various tissues. For example, HB-EGF has been shown to be important for wound healing (Marikovsky et al., 1993; Stoll et al., 1997; Tokumaru et al., 2000), arteriosclerosis (Nakata et al., 1996), blastocyst implantation (Das et al., 1994), and heart function (Iwamoto et al., 2003; Jackson et al., 2003; Yamazaki et al., 2003), whereas AREG has been implicated in mammary gland development (Sternlicht et al., 2005) and targeted expression of AREG in the epidermis results in a dermatosis with many similarities to psoriasis (Cook et al., 2004; Cook et al., 1997). Both AREG and HB-EGF have been shown to be important for retinoic acid-induced epidermal hyperproliferation (Rittie et al., 2006; Varani et al., 2001). TGF-α is implicated in hair follicle development and eye formation (Luetteke et al., 1993) whereas EREG appears to be a mediator of dermatitis and lung metastasis (Gupta et al., 2007; Shirasawa et al., 2004; Sternlicht et al., 2005). BTC null mice have no detectable defects (Luetteke et al., 1999) however, in transgenic animals it was recently shown that BTC regulates hair follicle development and angiogenesis during wound healing (Schneider et al., 2008).

In the present study we asked whether the autocrine expression of different EGFR ligands by KCs reflects the existence of nonredundant signaling mechanisms that become activated in different cellular contexts, and whether MPs are necessary for their activation. In pursuit of these objectives, we measured the effects of inhibitors of MP, EGFR, and EGF-like growth factor function in the contexts of wound-induced KC migration and proliferation. We also assessed the potency of various EGF-like growth factors on EGFR activation, as well as their effects on autocrine and LPA-induced ERK phosphorylation.

Results

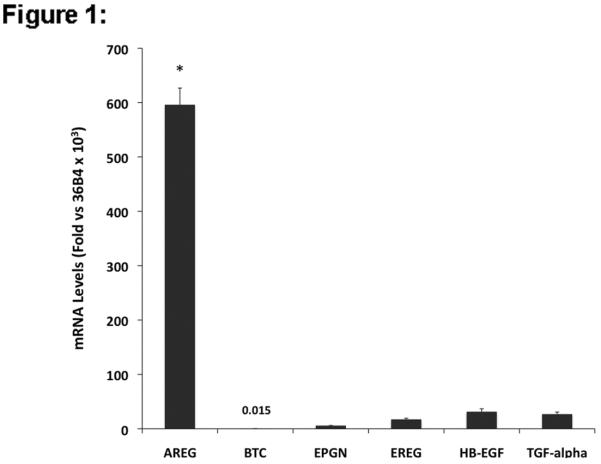

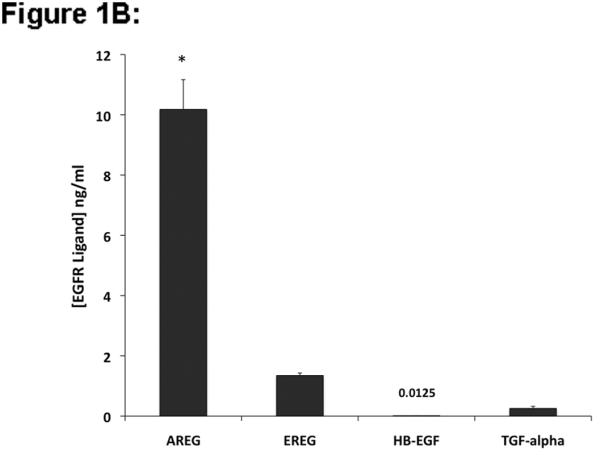

Expression of EGFR ligands in human KCs and normal and organ cultured human skin

To characterize the context-dependent function of EGFR ligands in KC physiology, we first measured EGF-like growth factor mRNA expression and protein shedding in subconfluent cultures of proliferating KCs using QRT-PCR and a multiplex EGFR ligand assay. As shown in Figure 1A, normal human KCs express high levels of AREG (transcript levels were 596 ‰ of 36B4 control gene expression) whereas EPGN, EREG, HB-EGF and TGF-α were expressed at significantly lower levels (transcript levels 5.8 ‰, 17.3 ‰, 31.3 ‰, and 26.9 ‰ of 36B4, respectively). BTC message levels in proliferating KCs were nearly 40,000 times less abundant than AREG transcripts. AREG was also the most abundant EGFR ligand protein shed into the culture medium (Fig. 1B), whereas EREG, HB-EGF and TGF-α were present at much lower levels. BTC and EPGN were not included in the study due to the lack of reliable detection reagents.

Figure 1.

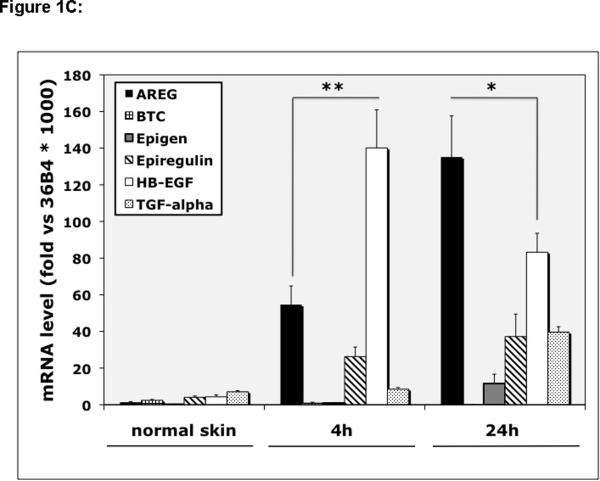

EGFR ligand expression and shedding in human KCs and normal and organ cultured human skin. (A) Normal human KCs were plated at 5% confluence, grown as described in Material and Methods and harvested ~70–95% confluence. Relative EGFR ligand mRNA expression was analyzed by QRT-PCR. Values represent fold-change versus the control gene 36B4 times 103 (mean +/− standard error of the mean [SEM], n=8). Asterisk denotes a significant difference in AREG expression relative to other ligands with p <10−6. (B) KCs were plated in 60mm dishes and grown as described above and 24 h accumulation of shed EGFR ligands in the culture medium of near-confluent KC cultures was assayed using a Multiplex Ligand Assay as described in Material and Methods. Data are expressed as ng of shed growth factor protein per ml of KC culture medium, mean +/− SEM, n=8, *= p<0.0001 vs all other growth factors shown. Soluble HB-EGF could only be detected in 4 out of 8 samples. (C) Total RNA was isolated from full-thickness 3 mm punch biopsies of normal human skin either immediately (control) or from biopsies subjected to human skin organ culture for 4h or 24h and EGFR ligand mRNA was analyzed by QRT-PCR. Data represent fold-change versus the control gene 36B4 times 103, n= 5–8, *= p<0.05, **= p<0.007.

We next measured EGFR ligand mRNA levels in normal and organ cultured human skin. As depicted in Figure 1C, expression of all EGF-like growth factors in normal human skin was very low (< 8 ‰ of 36B4 control gene transcript levels). However HB-EGF was strongly induced after 4 h of human skin organ culture (> 32-fold, increasing to 140 ‰ of 36B4). AREG expression was also markedly induced after 4 h of organ culture, but to a significantly lesser extent than HB-EGF. After 24 h of organ culture HB-EGF expression declined by nearly half whereas AREG expression doubled, making it the most strongly expressed EGFR ligand at this time point (135 ‰ of 36B4).

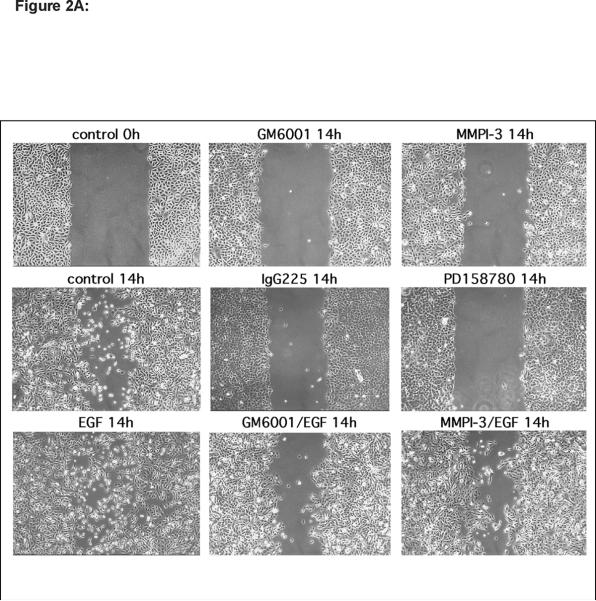

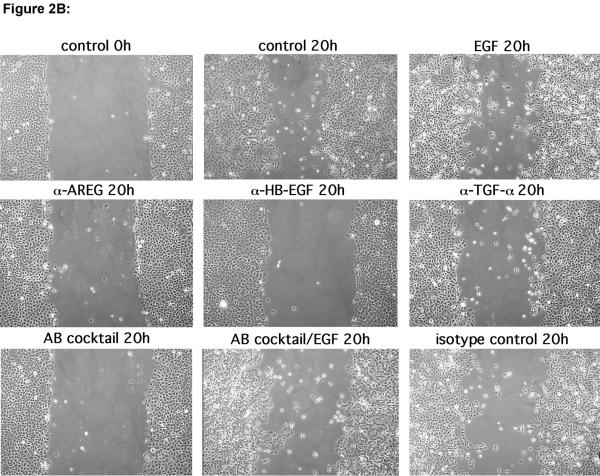

HB-EGF is a potent mediator of KC migration in vitro

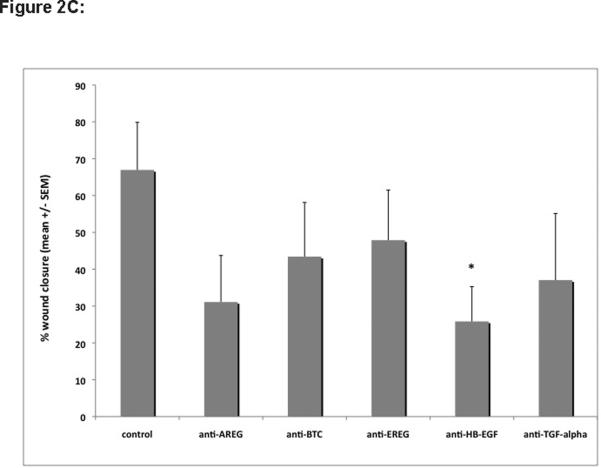

To determine the relative importance of various components of the EGFR system for KC migration, we performed scratch wound assays on near-confluent KC monolayers in the presence or absence of inhibitors of EGFR signaling, EGF-like growth factor function, and MP activity. As shown in Figure 2A, KCs showed vigorous migration in scratch wound assays that could only be slightly improved through addition of 10 ng/ml EGF. Interfering with EGFR signaling using the EGFR blocking antibody (Ab) 225 IgG or the pan-ErbB RTKI PD158780 or MP activity using either GM6001 or MMPI-3, markedly reduced scratch wound-induced migration. However, addition of EGF to MP inhibitors could only partially overcome the block, suggestive of MP-mediated aspects of KC migration other than EGFR activation. Similarly, scratch wound-induced migration was markedly reduced in the presence of EGFR neutralizing Abs (Figure 2B and C) with HB-EGF and AREG Abs displaying the strongest inhibition of KC migration. Addition of EGF to Ab-treated cultures restored their migratory phenotype, demonstrating a lack of cellular toxicity from Ab treatment.

Figure 2. HB-EGF is a potent inducer of KC migration in vitro.

(A) Scratch-wounded, confluent KC monolayers were incubated in basal M154 medium in the presence or absence of EGF (10 ng/ml), GM6001 (40 μM), MMPI-3 (25 μM), PD158780 (1 μM) and/or IgG225 (5 μg/ml). Scratch wounds were photographed by phase contrast microscopy after the indicated times. The results for individual panels are representative of at least two independent experiments.

(B) Scratch-wounded KC monolayers were incubated in basal M154 in the presence or absence of neutralizing Abs against EGFR ligands alone or in combination (Ab cocktail) or isotype control Abs (each at 5 μg/ml) with and without EGF (10 ng/ml) for 20 h.

(C) Confluent KC cultures were scratch-wounded and incubated for 18h to 24h as described above (Fig 2B). Digital images of representative areas were quantitated by measuring the scratch surface area using AxioVision-LE software (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Data are expressed as percent wound closure relative to controls at t = 0 h (% wound closure = [100 – ((scratch surface area at t = 18–24 h / surface area at t = 0 h)*100)], n=4 independent experiments, *= p ≤0.05 vs control.

(D) NTERT, NTERT-TR, and NTERT or NTERT-TR stably infected with lentivirus constructs encoding transmembrane (tm) and soluble (s) AREG (NTERT-tmAREG, NTERT-sAREG) and transmembrane and soluble HB-EGF (NTERT-TR-tmHB-EGF, NTERT-TR-sHB-EGF) were grown to confluence, scratch wounded and incubated in basal KSFM medium for 36 h in the presence or absence of 40 μM GM6001 (MPI). HB-EGF expression in NTERT-TR-HB-EGF cells was induced with 1 μg/ml TET at least 3 h prior to scratch wounding.

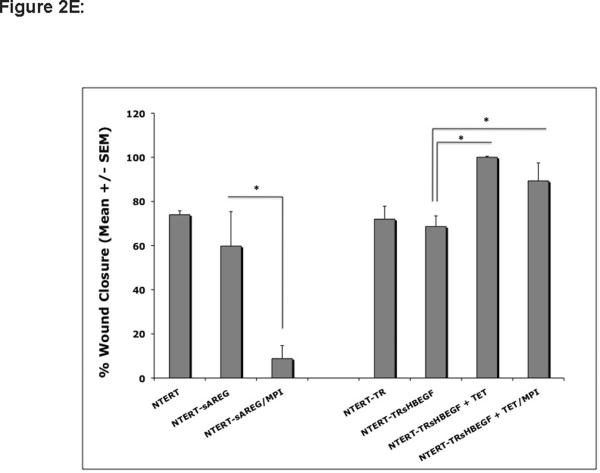

(E) Confluent cultures of NTERT and NTERT-TR with and without lentivirus-mediated expression of sAREG or sHB-EGF were scratched wounded and incubated for 18 h to 36 h in basal KSFM in the presence or absence of 40 μM GM6001 or 25 μM MMPI-3 as described above (Fig 2D). Tetracycline-induced expression of HB-EGF in NTERT-TRsHB-EGF cells is indicated by “+ TET”. Digital images of representative areas were quantitated by measuring the scratch surface area as described in Fig 2C, n=3, except N-TERT and N-TERT-TR n=2, *= p <0.05.

(F) Equal amounts of RIPA cell lysates of control N-TERT or N-TERT stably infected with lentiviruses encoding AREG and HB-EGF were analyzed by ELISA for AREG or HB-EGF expression respectively, as described in Material and Methods. Data are expressed as ng of AREG or HB-EGF protein per ml of RIPA lysates, n=3 for AREG and controls and n=7–12 for HB-EGF and controls, *= p<0.001 relative to uninfected controls.

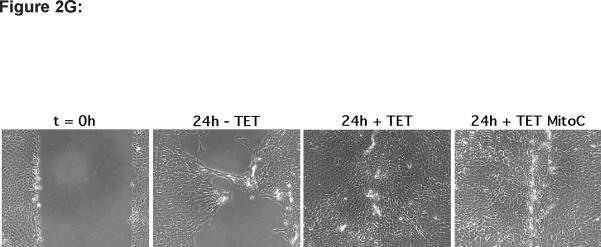

(G) N-TERT-TR-sHB-EGF KC were grown and scratch wounded as described above and followed by incubation in basal KSFM medium for 24 h in the presence or absence of TET with and without 1 μg/ml mitomycin C. Results are representative of two separate experiments.

Because KCs express and shed much less HB-EGF than AREG (Fig. 1), yet neutralizing Abs against HB-EGF were as effective as AREG Abs to block KC migration, we wondered whether exogenous expression of HB-EGF might improve KC migration to a greater extent than exogenous expression of AREG. To address this, N-TERT KCs stably infected with lentivirus constructs encoding transmembrane and soluble forms of HB-EGF and AREG were tested in scratch wound assays as above. As shown in Figure 2D and quantitated in Figure 2E, TET-induced expression of the full-length transmembrane (tm) form of HB-EGF (tmHB-EGF) or a secreted form lacking the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains (sHB-EGF) markedly improved KC migration compared to N-TERT-TR control cells or N-TERT-TR-HB-EGF without TET-induced expression of sHB-EGF. Interestingly, TET-induced expression of HB-EGF resulted in a marked piling up of cells upon closure of scratch wounds. In contrast, lentivirus-mediated, constitutive expression of soluble AREG (sAREG) or its transmembrane form (tmAREG) did not improve KC migration relative to control cells (NTERT). As expected, MP inhibitor (MPI) treatment of KCs reduced migration in cells expressing tmHB-EGF, but not in cells expressing sHB-EGF. Unexpectedly, however, MPI treatment significantly reduced cell migration in KCs expressing soluble AREG. Our data in Figure 2F confirmed increased expression of AREG and HB-EGF in lentivirus infected N-TERT KCs and demonstrate that scratch wound migration is not blocked by the proliferation inhibitor mitomycin C (Fig. 2G).

Autocrine KC proliferation and ERK phosphorylation are selectively regulated by MP-dependent release of AREG

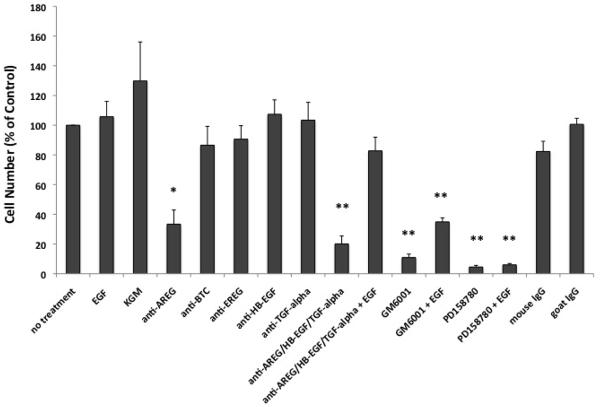

To address the importance of individual growth factors on KC growth, we performed growth assays in the presence or absence of EGFR ligand neutralizing Abs. As depicted in Figure 3, incubation of KCs with anti-AREG Abs significantly reduced KC growth by more than 66 % (p< 0.005), whereas Abs directed against other ligands had only modest effects on KC growth. Similar to their effects on KC migration, PD158780 and GM6001 markedly reduced KC growth. Addition of exogenous EGF (1 ng/ml) to KCs incubated with GM6001 could only partially restore growth but had no effect on KCs incubated in the presence of PD158780. In contrast, EGF treatment markedly improved KC growth in cell cultures incubated with a cocktail of all three neutralizing Abs (AREG, HB-EGF, and TGF-α), demonstrating a lack of Ab toxicity.

Figure 3.

Neutralizing antibodies against AREG selectively block KC growth. KCs were incubated in basal M154 medium in the presence of blocking antibodies against AREG, BTC, EREG, HB-EGF, and TGF-α or isotype controls (each at 5 μg/ml), 40 μM GM6001 or 1 μM PD158780 with and without 1 ng/ml EGF. After an additional 7–9 days of incubation, cell growth was assessed using the 3-(4,5dimethyldiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium (MTT) assay (Roche). KGM denotes fully supplemented KC growth medium. Each data point represents the mean OD570 reading for duplicate culture conditions. Data are expressed as percent of untreated controls, n= 3–5, with *= p<0.005 and **= p<0.0005 relative to “no treatment” controls.

Because ERK is an important regulator of cell proliferation (Hobbs et al., 2004), we tested whether AREG also selectively regulates the high levels of ERK phosphorylation that we have consistently observed in KCs even after 48 h of growth factor deprivation (Kansra et al., 2004; Stoll et al., 2002). As shown in Figure 4, neutralizing antibodies against AREG strongly reduced ERK phosphorylation in KCs incubated in growth factor-free medium whereas Abs against four other EGFR ligands had little or no inhibitory activity on this process. As expected, ERK phosphorylation was strongly inhibited by the MEK inhibitor U0126, the pan-ErbB RTKI PD158780, and the MPI GM6001. Addition of EGF restored NHK ERK phosphorylation in the presence of GM6001 and in the presence of an Ab cocktail against all five EGFR ligands but not in cells incubated with PD158780 or U0126.

Figure 4.

Autocrine ERK phosphorylation is selectively regulated by AREG. KCs were growth factor-depleted for 48 h as described in Material and Methods and incubated for 2 h in fresh basal M154 in the presence or absence of neutralizing antibodies against EGF-like growth factors (each at 5 μg/ml) or GM6001 (40 μM), PD158780 (1 μM), or U0126 (10 μM) in the presence or absence of 100 ng/ml EGF. Equal amounts of RIPA were analyzed by western blotting with antibodies against ERK and phospho-ERK. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

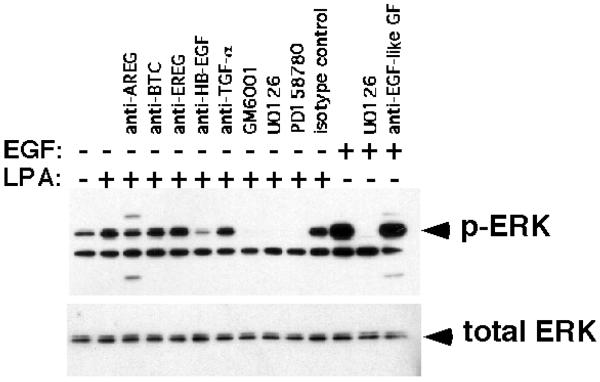

LPA-induced ERK phosphorylation is mediated by MP-dependent release of HB-EGF

Transactivation of EGFR by GPCR ligands including LPA is a mechanism that requires proteolytic release of EGFR ligands from their transmembrane-bound precursors (Sanderson et al., 2006) and LPA-mediated ERK activation has been previously demonstrated (Kranenburg and Moolenaar, 2001). Therefore, we tested whether LPA could induce ERK phosphorylation in KCs and whether neutralizing Abs against EGFR ligands could block this process. As can be seen in Figure 5, LPA treatment of KCs maintained under autocrine conditions for 48 h prior to assay led to a marked increase in ERK phosphorylation that could be blocked after treatment with the MPI GM6001, the MEK inhibitor U0126, and the ErbB RTKI PD158780. Interestingly and in contrast to the data presented in Figure 4, LPA-induced ERK phosphorylation was markedly inhibited by HB-EGF antibodies whereas other EGFR ligand Abs or IgG isotype controls had little or no effect.

Figure 5.

HB-EGF mediates LPA-stimulated ERK phosphorylation. KCs were depleted of growth factors by incubation in basal M154 medium for 48 h followed by treatment with goat isotype control (for HB-EGF) or neutralizing Abs against EGFR ligands (each at 5 μg/ml) alone or in combination (anti-EGF-like GF), GM6001 (40 μM), PD158780 (1 μM), or U0126 (10 μM) for 1 h followed by treatment with EGF (10 ng/ml) or LPA (10 μM) for 10 or 20 min, respectively. Protein lysates were assayed for phospho-ERK and total ERK by western blotting as described in Material and Methods. The slight reduction of ERK phosphorylation in the presence of AREG Abs might be related to the component of the total signal that is due to basal ERK phosphorylation and therefore sensitive to AREG antibodies (see Fig. 4). The band underneath the phospho-ERK signal has been consistently observed with the mouse mono- but not with the rabbit polyclonal phospho-ERK Ab (Fig 4) from Cell Signaling Technologies. Its identity is unknown, however, it does not appear to be regulated in response to different treatments. The additional bands in the anti-AREG lane are due to a cross-reaction of the goat anti-mouse-HRP labeled secondary antibody with the AREG neutralizing antibody. The results shown are representative for three independent experiments.

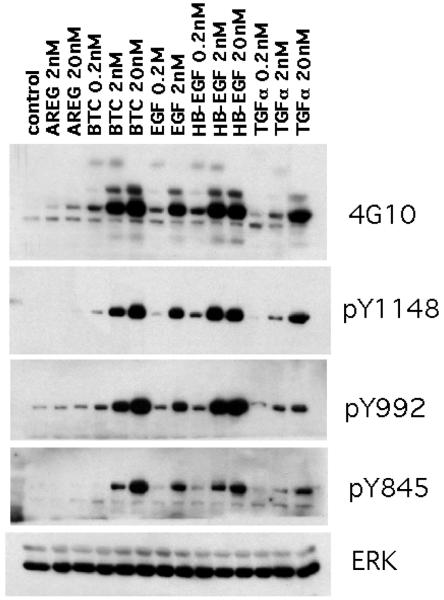

ErbB ligands differ in their ability to stimulate EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation

We also measured the potency of the various EGF-like growth factors to induce total tyrosine phosphorylation as well as tyrosine residue-specific EGFR phosphorylation in KCs. As can be seen in Figure 6, EGF, HB-EGF and BTC were nearly equipotent in their ability to stimulate total tyrosine phosphorylation of proteins in the 170 – 180 kDa size range (4G10). The same three growth factors also induced a very similar pattern of tyrosine phosphorylation on EGFR residues 1148, 992 and 845. In contrast, TGF-α and particularly AREG were much less potent as inducers of total and residue-specific EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation, with no visible phosphorylation of EGFR pY845 even after treatment with 20 nM AREG.

Figure 6.

EGFR ligands differ in their ability to stimulate EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation. KCs were grown in M154 medium until ~ 40–50% confluence, growth factor depleted for 48 h, followed by growth factor treatment for 10 min at 37°C in fresh M154 as indicated. Equal amounts of RIPA lysates were analyzed by western blotting with antibodies indicated to the right of the panels. Total ERK served as a control for equal protein loading. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

Discussion

Autocrine EGFR receptor signaling controls multiple KC functions including migration, proliferation, differentiation and survival (Danilenko et al., 1995; Klein et al., 1992; Nanney and King, 1996; Pastore et al., 2007; Stoll et al., 1998). Acute stimulation of KCs with high concentrations of EGF or other EGFR ligands leads to increased expression of multiple EGF family members including AREG, HB-EGF and TGF-α (Barnard et al., 1994; Shirakata et al., 2000; Stoll and Elder, 1999). Although KCs express multiple EGF-like growth factors in an autocrine fashion, their importance and specific function in different cellular contexts has been incompletely characterized, and it remains unclear why the ErbB signaling network relies on multiple ligands. To address these questions, we started our investigation by assessing the relative expression of EGF ligands in cultured KCs and normal and organ cultured human skin (Fig. 1). Using QRT-PCR, we found that proliferating normal human KCs express at least 19 times more AREG mRNA than EPGN, EREG, HB-EGF or TGF-α, and that BTC mRNA was nearly undetectable. Similarly, using a multiplex EGFR ligand assay, we found that AREG was also the most abundant EGF-like growth factor shed into the culture medium, whereas EREG, TGF-α, and HB-EGF were very close to our detection limit.

Our finding that AREG is the most abundantly expressed and shed EGF-like growth factor in KCs may largely explain why autocrine KC growth and ERK phosphorylation were selectively blocked by antibodies against AREG but not by antibodies against four other EGF-like growth factors (Fig. 3 and 4). However, it may not be the only explanation. AREG has a much lower binding affinity for EGFR than does EGF, due to the lack of a conserved leucine residue necessary for high affinity binding to EGFR (Adam et al., 1995). Interestingly, EPGN is also a low affinity EGFR ligand with a hundred-fold lower binding affinity than EGF, yet its mitogenic potential is far superior to that of EGF or TGF-α (Kochupurakkal et al., 2005). The authors of this study suggested that the high mitogenic potential of EPGN might be due to evasion of desensitization; e.g., receptor-mediated endocytosis targeting receptor-ligand complexes for intracellular degradation. We confirm that HB-EGF, BTC, and EGF are much more potent activators of the KC EGFR than is AREG (Fig. 6). Thus, it is possible that the strong dependence of KC proliferation on AREG might be further explained by relatively weak desensitization of ligand-receptor complexes.

Our study also confirm findings from earlier studies showing that AREG antibodies block growth of cultured KCs under autocrine conditions (Bhagavathula et al., 2005), whereas TGF-α Abs had no effect under these conditions (Pittelkow et al., 1993). However in those studies the function of EGFR ligands other than AREG and TGF-α for autocrine KC growth was not assessed. Similarly, we have previously shown that AREG antibodies abrogate autocrine ERK phosphorylation (Kansra et al., 2004). In the present study, we show that four other EGFR ligands are not important for this process.

Overexpression of AREG in transgenic mice leads to a hyperproliferative skin phenotype with many similarities to psoriasis (Cook et al., 2004; Cook et al., 1997). Furthermore, a humanized antibody against AREG also markedly blocked the psoriatic phenotype of human skin grafts on immunodeficient mice (Bhagavathula et al., 2005). While it is tempting to speculate that the growth-stimulatory properties of AREG in culture are responsible for the profound epidermal hyperplasia characteristic of psoriasis, this remains to be proven. Recently, AREG has been shown to be overexpressed in synovium and synovial fluid as well as synovial fluid-derived mononuclear cells of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients, relative to patients with osteoarthritis (OA) (Yamane et al., 2008). Notably, transgenic mice engineered to overexpress AREG in basal keratinocytes developed a severe inflammatory arthritis (Cook et al., 1997). Thus, it is possible that AREG may play a role in the inflammatory cascade of psoriasis, instead of or along with a direct effect on KC proliferation.

The low expression of BTC in proliferating KCs was not surprising, as it was previously shown that its expression is restricted to the fully differentiated, upper suprabasal layers of the skin (Piepkorn et al., 2003; Rittie et al., 2006). It is possible that BTC might be more important for KC differentiation rather than proliferation. On the other hand, forced expression of BTC in the basal layer of transgenic mice results in significantly increased KC proliferation without affecting differentiation (Schneider et al., 2008). Basal overexpression of BTC might lead to different physiological effects than its normal expression in suprabasal layers, which also display different ErbB expression profiles (Stoll et al., 2001). In the present study we also show that the recently discovered EPGN (Strachan et al., 2001) is another EGFR ligand expressed by KCs (Fig. 1).

In contrast to cultured KCs, expression of all EGF-like growth factors in normal skin was very low. However, HB-EGF and AREG were strongly induced in human skin organ culture, an in vitro model displaying many similarities to cutaneous wound healing (Bhora et al., 1995; Eisen, 1969; Hebda, 1988; Mackie et al., 1988; Reaven and Cox, 1968; Sarkany et al., 1965; Stoll et al., 1997; Stoll et al., 2002) (Fig. 1C). Our recent data confirm and extend earlier data from our laboratories about EGFR ligand expression in normal and organ cultured skin (Rittie et al., 2007; Stoll et al., 1997; Stoll et al., 2002). However, using QRT-PCR instead of northern blotting, we were able to quantitate the expression levels of all EGFR ligands and show that EREG and TGF-α are also strongly induced in the organ culture system. Furthermore, our data demonstrate a sequential regulation of HB-EGF and AREG expression, and suggest that HB-EGF may be important in the earliest phases of wound healing, with AREG increasing later during the process. This is interesting because wound healing can be divided into an early phase during which KCs migrate but do not proliferate and a later phase characterized by vigorous KC proliferation (Bhora et al., 1995; Hebda, 1988; Marks et al., 1972; Stenn, 1978; Stoll et al., 1997).

The importance of AREG for autocrine KC proliferation (Fig. 3) might explain its increased expression during the later phase of organ culture. Interestingly, increased expression of AREG during wound healing has been reported (Schelfhout et al., 2002). The early expression of HB-EGF in this model and its importance in scratch wound assays (Fig. 2), strongly suggest an important function of HB-EGF during the early migration phase of wound healing. Consistent with this, it has been shown that skin wound closure was markedly impaired in KC-specific HB-EGF-deficient mice (Shirakata et al., 2005). Our data also confirm earlier findings that KC migration is sensitive to EGFR, HB-EGF and MP inhibitors (Tokumaru et al., 2000). However, in those experiments KC migration was assessed on tissue culture plates coated with type-1 collagen. Although KC migration was sensitive to antibodies against several ligands, expression of soluble HB-EGF markedly improved KC migration even in the presence of MP inhibitors (Fig. 2). In contrast, our findings demonstrate that soluble AREG by itself is not sufficient to promote KC migration, but instead requires the proteolytic release of one or more additional growth factor(s).

LPA is an important constituent of blood and serum and has been implicated in many cellular processes such as migration, proliferation, cancer and wound healing (Watterson et al., 2007). The strong activation of EGFR by HB-EGF (Figure 6) and our data showing that LPA-induced ERK phosphorylation (Figure 5) depends on MP-mediated release of HB-EGF further suggest an important role of HB-EGF during the early phases of wound healing. The finding that an anti-HB-EGF mAb blocks LPA-induced ERK phosphorylation is in marked contrast to the specific blockade of autocrine ERK phosphorylation by AREG Abs and the lack thereof in the presence of HB-EGF Abs (Figure 4).

We cannot exclude that differential ligand affinities of neutralizing antibodies affect some of the conclusions of the growth and migration assays or other comparative analyses of this study. Ultimately, these findings will have to be confirmed using RNAi-mediated gene knockdown in human KCs.

In aggregate, our data demonstrate that MP-mediated release of membrane-bound EGF-like growth factors is required for EGFR-dependent autocrine ERK phosphorylation, migration and proliferation of normal human KCs. We find that autocrine KC proliferation and ERK phosphorylation are selectively regulated by MP-dependent release of AREG, whereas proteolytic release of HB-EGF is required for KC migration as well as LPA-induced ERK phosphorylation. These data suggest important but distinct functions of HB-EGF and AREG during the migratory and proliferative phases of cutaneous wound healing, respectively.

Material and Methods

Reagents

The MP inhibitors (MPI) GM6001 and MMP inhibitor III (MMPI-3), the MEK inhibitor U0126, and the pan-ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (RTKI) PD158780 were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Recombinant human EGF was from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ) and AREG, BTC, EREG, HB-EGF and TGF-α and their cognate Abs were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Anti-ERK and anti-phospho ERK Abs were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Abs against human EGFR were from Labvision (Freemont, CA), Cell Signaling Technology and from Biosource/Invitrogen. The anti-phosphotyrosine mAb 4G10 and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or FITC conjugated anti-mouse, anti-rabbit and anti-goat Abs were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). All other chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis MO) or Invitrogen, (Carlsbad, CA).

Human subjects and organ culture

Human skin full-thickness punch biopsies (3 mm) were collected from sun-protected skin (buttocks) of healthy volunteers after having obtained informed consent according to a protocol approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All experiments involving human subjects were performed in adherence to the Helsinki Guidelines. Skin samples were snap frozen immediately or after having been subjected to organ culture by incubation in basal M154 medium (Cascade Biologics, Portland, OR) for 4 and 24 h at 37°C/5% CO2 as previously described (Stoll et al., 2002) and were processed for RNA isolation as described below.

Cell Culture

Normal human KCs (passages 2–4) were cultured in low-calcium, serum free M154 medium (KGM) as previously described (Stoll et al., 2001). Human embryonic kidney cells (293FT, Invitrogen) were grown in Dulbeco's Modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco). The immortalized, non-transformed KC cell line N-TERT-2G was grown in keratinocyte SFM medium (KFSM, Gibco) as previously described (Dickson et al., 2000).

Lentivirus-mediated gene expression

The cDNAs encoding the full-length (transmembrane) or extracellular (soluble) forms of AREG and HB-EGF were cloned into the lentiviral expression vectors pLenti6/CMV/V5-DEST (full-length AREG) or pLenti4/TO/V5-DEST (soluble forms of AREG and HB-EGF and full-length HB-EGF) and used to produce infectious lentivirus particles according to the manufacturers instructions (Invitrogen). Stably transduced KC cell lines with constitutive expression of soluble or transmembrane AREG were generated by infection of N-TERT-2G KC with the corresponding lentivirus constructs followed by antibiotic selection with 8 μg/ml blasticidin or 200 μg/ml zeocin and the resulting cell lines were termed N-TERT-sAREG (expressing the soluble form of AREG) and N-TERT-tmAREG (expressing full-length, transmembrane AREG). To generate stably transduced cell lines with inducible expression of HB-EGF, N-TERT-2G KCs were first infected with TR lentivirus (pLenti6/TR construct) as above. After selection with blasticidin, the resulting cell line, termed N-TERT-TR, was infected with lentiviruses encoding HB-EGF constructs as described above followed by antibiotic selection with zeocin. Stably transduced cell lines expressing the soluble or transmembrane forms of HB-EGF ((N-TERT-TRsHB-EGF and N-TERT-TR-tmHB-EGF, respectively) were used for experiments as described below and gene expression was induced with 1 μg/ml TET (Invitrogen).

RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR)

Total RNA from KCs or frozen skin was isolated using RNeasy mini kits with on-column DNase digestion (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total RNA was reverse transcribed using the Applied Biosystems High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit. cDNA equivalent to 5–40 ng of total RNA was used for QRT- PCR using pre-validated TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for AREG (# Hs00155832), BTC (# Hs00156140), EREG (# Hs00914313, EPGN (# Hs02385425), HB-EGF (# Hs00181813, TGF-α (# Hs00608187) and ribosomal protein large P0 (RPLP0 or 36B4, # Hs99999902) (Laborda, 1991; Minner and Poumay, 2008). Data are expressed as fold-change relative to 36B4 multiplied by 103 (fold-change versus 36B4 = 2 –(CT target -CT 36B4)).

In vitro wound healing assays

KCs were plated, grown and wounded as previously described (Kansra et al., 2005; Stoll et al., 2003). Wounded cultures were incubated with basal M154 medium or KSFM in the presence or absence of EGF (10 ng/ml) with or without MMPI-3 (25 μM) or GM6001 (40 μM), IgG225 (5 μg/ml), PD158780 (1 μM), or neutralizing Abs directed against EGFR ligands (each at 5 μg/ml) or isotype control Abs. KC migration was assessed by phase contrast microscopy and documented by photography. Digital images were quantified using AxioVision-LE software (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Cell Growth Assays

KCs were plated at 1,000–2000 cells/cm2 in complete M154 and allowed to attach for 20 h. The cells were then incubated in basal M154 in the presence or absence of EGF (1 ng/ml) with or without GM6001, PD158780, or blocking Abs and isotype controls as described above. KC growth was assessed using the 3-(4,5dimethyldiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium (MTT) assay (Roche).

Western blotting

KCs were grown to 40 to 50% confluence and deprived of growth factors by incubation in basal M154 medium for 48 h. The cells were incubated in fresh M154 in the presence or absence of U0126 (10 μM), PD158780 (1 μM), GM6001 (40 μM) or EGFR ligand blocking antibodies (5 μg/ml each) with or without stimulation for 10 min with EGF (16.5 nM) or 20 min with LPA (10 μM). Cells were harvested with RIPA buffer and analyzed by western blotting as previously described (Kansra et al., 2004; Stoll et al., 2002).

Multiplex EGFR ligand assay

A multiplex EGFR ligand assay was developed by crosslinking Abs against AREG, BTC, EREG, HB-EGF and TGF-α (R&D Systems) with a set of fluorescently-dyed Bio-Plex microspheres (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, microspheres coupled with EGFR ligand Abs were incubated with KC conditioned medium on 96-well microplates followed by incubation with EGFR ligand-specific biotinylated Abs. After addition of streptavidin-PE (Bio-Rad), fluorescence was measured using a Bio-Plex 200 system (Bio-Rad). EGFR ligand concentration was determined in duplicates using a 5-parameter logistic curve fit with a cocktail of recombinant EGFR ligands used in threefold dilutions to generate an 8-point standard curve for each ligand.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

EGFR ligands in RIPA cell lysates were detected by sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems) using anti-AREG and anti-HB-EGF antibodies as previously described (Kansra et al., 2004).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean +/− standard error of the means (SEM), with n for independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using paired or independent Student's t-test (two-tailed). P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Suzan Rehbine for her excellent technical assistance with skin biopsies and Dr. James Rheinwald (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for providing N-TERT-2G keratinocytes. This work was in part supported by the National Institute for Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease (NIAMS), National Institutes of Health (NIH award K01 AR050462 and R03 AR049420 to SWS and R01 AR 052889 to JTE) and by a Chesebrough Pond's Lever Brothers Dermatology Foundation Research Career Development Award (SWS). JTE is supported by the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Hospital.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- Ab

antibody

- AREG

amphiregulin

- BTC

betacellulin

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

EGF receptor

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EPGN

epigen

- EREG

epiregulin

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GF

growth factor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HB-EGF

heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- KC

keratinocyte

- MP

metalloproteinase

- QRT-PCR

quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

- TET

tetracycline

- TGF-α

transforming growth factor-α

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Adam R, Drummond DR, Solic N, Holt SJ, Sharma RP, Chamberlin SG, et al. Modulation of the receptor binding affinity of amphiregulin by modification of its carboxyl terminal tail. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1266:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)00224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard JA, Graves Deal R, Pittelkow MR, DuBois R, Cook P, Ramsey GW, et al. Auto- and cross-induction within the mammalian epidermal growth factor-related peptide family. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22817–22822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagavathula N, Nerusu KC, Fisher GJ, Liu G, Thakur AB, Gemmell L, et al. Amphiregulin and epidermal hyperplasia: amphiregulin is required to maintain the psoriatic phenotype of human skin grafts on severe combined immunodeficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1009–1016. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62322-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhora FY, Dunkin BJ, Batzri S, Aly HM, Bass BL, Sidawy AN, et al. Effect of growth factors on cell proliferation and epithelialization in human skin. J Surg Res. 1995;59:236–244. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1995.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess AW, Cho HS, Eigenbrot C, Ferguson KM, Garrett TP, Leahy DJ, et al. An open-and-shut case? Recent insights into the activation of EGF/ErbB receptors. Mol Cell. 2003;12:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citri A, Yarden Y. EGF-ERBB signalling: towards the systems level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:505–516. doi: 10.1038/nrm1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey RJ, Jr., Derynck R, Wilcox JN, Bringman TS, Goustin AS, Moses HL, et al. Production and auto-induction of transforming growth factor-alpha in human keratinocytes. Nature. 1987;328:817–820. doi: 10.1038/328817a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PW, Brown JR, Cornell KA, Pittelkow MR. Suprabasal expression of human amphiregulin in the epidermis of transgenic mice induces a severe, early-onset, psoriasis-like skin pathology: expression of amphiregulin in the basal epidermis is also associated with synovitis. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:347–356. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2004.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PW, Mattox PA, Keeble WW, Pittelkow MR, Plowman GD, Shoyab M, et al. A heparin sulfate-regulated human keratinocyte autocrine factor is similar or identical to amphiregulin. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2547–2557. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PW, Piepkorn M, Clegg CH, Plowman GD, DeMay JM, Brown JR, et al. Transgenic expression of the human amphiregulin gene induces a psoriasis-like phenotype. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2286–2294. doi: 10.1172/JCI119766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilenko DM, Ring BD, Lu JZ, Tarpley JE, Chang D, Liu N, et al. Neu differentiation factor upregulates epidermal migration and integrin expression in excisional wounds. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:842–851. doi: 10.1172/JCI117734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das SK, Wang XN, Paria BC, Damm D, Abraham JA, Klagsbrun M, et al. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor gene is induced in the mouse uterus temporally by the blastocyst solely at the site of its apposition: a possible ligand for interaction with blastocyst EGF- receptor in implantation. Development. 1994;120:1071–1083. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Potter IY, Poumay Y, Squillace KA, Pittelkow MR. Human EGF receptor (HER) family and heregulin members are differentially expressed in epidermal keratinocytes and modulate differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2001;271:315–328. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson MA, Hahn WC, Ino Y, Ronfard V, Wu JY, Weinberg RA, et al. Human keratinocytes that express hTERT and also bypass a p16(INK4a)-enforced mechanism that limits life span become immortal yet retain normal growth and differentiation characteristics. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1436–1447. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1436-1447.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen AZ. Human skin collagenase: localization and distribution in normal human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1969;52:442–448. doi: 10.1038/jid.1969.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GP, Nguyen DX, Chiang AC, Bos PD, Kim JY, Nadal C, et al. Mediators of vascular remodelling co-opted for sequential steps in lung metastasis. Nature. 2007;446:765–770. doi: 10.1038/nature05760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Higashiyama S, Asada H, Hashimura E, Kobayashi T, Sudo K, et al. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor is an autocrine growth factor for human keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20060–20066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebda PA. Stimulatory effects of transforming growth factor-beta and epidermal growth factor on epidermal cell outgrowth from porcine skin explant cultures. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:440–445. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12476480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs RM, Silva-Vargas V, Groves R, Watt FM. Expression of activated MEK1 in differentiating epidermal cells is sufficient to generate hyperproliferative and inflammatory skin lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;23:503–515. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto R, Mekada E. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor: a juxtacrine growth factor. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11:335–344. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(00)00013-7. In Process Citation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto R, Yamazaki S, Asakura M, Takashima S, Hasuwa H, Miyado K, et al. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor and ErbB signaling is essential for heart function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3221–3226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537588100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson LF, Qiu TH, Sunnarborg SW, Chang A, Zhang C, Patterson C, et al. Defective valvulogenesis in HB-EGF and TACE-null mice is associated with aberrant BMP signaling. Embo J. 2003;22:2704–2716. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansra S, Stoll SW, Johnson JL, Elder JT. Autocrine extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation in normal human keratinocytes: Metalloproteinase-mediated release of amphiregulin triggers signaling from ErbB1 to ERK. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4299–4309. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansra S, Stoll SW, Johnson JL, Elder JT. Src family kinase inhibitors block amphiregulin-mediated autocrine ErbB signaling in normal human keratinocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1145–1157. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Fisher GJ, Jensen TC, Mendelsohn J, Voorhees JJ, Elder JT. Regulation of TGF-alpha expression in human keratinocytes: PKC- dependent and -independent pathways. J Cell Physiol. 1992;151:326–336. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041510214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochupurakkal BS, Harari D, Di-Segni A, Maik-Rachline G, Lyass L, Gur G, et al. Epigen, the last ligand of ErbB receptors, reveals intricate relationships between affinity and mitogenicity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8503–8512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranenburg O, Moolenaar WH. Ras-MAP kinase signaling by lysophosphatidic acid and other G protein-coupled receptor agonists. Oncogene. 2001;20:1540–1546. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laborda J. 36B4 cDNA used as an estradiol-independent mRNA control is the cDNA for human acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein PO. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3998. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetteke NC, Qiu TH, Fenton SE, Troyer KL, Riedel RF, Chang A, et al. Targeted inactivation of the EGF and amphiregulin genes reveals distinct roles for EGF receptor ligands in mouse mammary gland development. Development. 1999;126:2739–2750. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.12.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetteke NC, Qiu TH, Peiffer RL, Oliver P, Smithies O, Lee DC. TGF alpha deficiency results in hair follicle and eye abnormalities in targeted and waved-1 mice. Cell. 1993;73:263–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90228-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie EJ, Halfter W, Liverani D. Induction of tenascin in healing wounds. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2757–2767. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marikovsky M, Breuing K, Liu PY, Eriksson E, Higashiyama S, Farber P, et al. Appearance of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor in wound fluid as a response to injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3889–3893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks R, Bhogal B, Dawber RP. The migratory property of epidermis in vitro. Arch Dermatol Forsch. 1972;243:209–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00595497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minner F, Poumay Y. Candidate Housekeeping Genes Require Evaluation before their Selection for Studies of Human Epidermal Keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2008 doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi E, Higashiyama S, Nakagawa T, Hayashi N, Taniguchi N. Membrane-anchored heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor acts as a tumor survival factor in a hepatoma cell line. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14349–14355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata A, Miyagawa J, Yamashita S, Nishida M, Tamura R, Yamamori K, et al. Localization of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor in human coronary arteries. Possible roles of HB-EGF in the formation of coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1996;94:2778–2786. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanney LB, King LE. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-alpha. In: Clark RAF, editor. The Molecular and Cellular Biology of Wound Repair. 2nd ed. Plenum Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pastore S, Mascia F, Mariani V, Girolomoni G. The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor System in Skin Repair and Inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Reddy P, Stocking KL, Sunnarborg SW, Lee DC, et al. An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science. 1998;282:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1281. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepkorn M, Pittelkow MR, Cook PW. Autocrine regulation of keratinocytes: the emerging role of heparin-binding, epidermal growth factor-related growth factors. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:715–721. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepkorn M, Predd H, Underwood R, Cook P. Proliferation-differentiation relationships in the expression of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-related factors and erbB receptors by normal and psoriatic human keratinocytes. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s00403-003-0391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittelkow MR, Cook PW, Shipley GD, Derynck R, Coffey RJ., Jr. Autonomous growth of human keratinocytes requires epidermal growth factor receptor occupancy. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4:513–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press MF, Cordon-Cardo C, Slamon DJ. Expression of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in normal human adult and fetal tissues. Oncogene. 1990;5:953–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigent SA, Lemoine NR, Hughes CM, Plowman GD, Selden C, Gullick WJ. Expression of the c-erbB-3 protein in normal human adult and fetal tissues. Oncogene. 1992;7:1273–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven EP, Cox AJ. Behavior of adult human skin in organ culture. II. Effects of cellophane tape stripping, temperature, oxygen tension, pH and serum. J Invest Dermatol. 1968;50:118–128. doi: 10.1038/jid.1968.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittie L, Kansra S, Stoll SW, Li Y, Gudjonsson JE, Shao Y, et al. Differential ErbB1 signaling in squamous cell versus basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:2089–2099. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittie L, Varani J, Kang S, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. Retinoid-induced epidermal hyperplasia is mediated by epidermal growth factor receptor activation via specific induction of its ligands heparin-binding EGF and amphiregulin in human skin in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:732–739. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson MP, Dempsey PJ, Dunbar AJ. Control of ErbB signaling through metalloprotease mediated ectodomain shedding of EGF-like factors. Growth Factors. 2006;24:121–136. doi: 10.1080/08977190600634373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkany I, Grice K, Caron GA. Organ culture of adult human skin. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:65–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1965.tb14602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelfhout VR, Coene ED, Delaey B, Waeytens AA, De Rycke L, Deleu M, et al. The role of heregulin-alpha as a motility factor and amphiregulin as a growth factor in wound healing. J Pathol. 2002;198:523–533. doi: 10.1002/path.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MR, Antsiferova M, Feldmeyer L, Dahlhoff M, Bugnon P, Hasse S, et al. Betacellulin regulates hair follicle development and hair cycle induction and enhances angiogenesis in wounded skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1256–1265. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakata Y, Kimura R, Nanba D, Iwamoto R, Tokumaru S, Morimoto C, et al. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor accelerates keratinocyte migration and skin wound healing. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2363–2370. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakata Y, Komurasaki T, Toyoda H, Hanakawa Y, Yamasaki K, Tokumaru S, et al. Epiregulin, a novel member of the epidermal growth factor family, is an autocrine growth factor in normal human keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5748–5753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasawa S, Sugiyama S, Baba I, Inokuchi J, Sekine S, Ogino K, et al. Dermatitis due to epiregulin deficiency and a critical role of epiregulin in immune-related responses of keratinocyte and macrophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13921–13926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404217101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AB, Tsukada T, Zent R, Harris RC. Membrane-associated HB-EGF modulates HGF-induced cellular responses in MDCK cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1365–1379. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenn KS. The role of serum in the epithelial outgrowth of mouse skin explants. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:411–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1978.tb06534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht MD, Sunnarborg SW, Kouros-Mehr H, Yu Y, Lee DC, Werb Z. Mammary ductal morphogenesis requires paracrine activation of stromal EGFR via ADAM17-dependent shedding of epithelial amphiregulin. Development. 2005;132:3923–3933. doi: 10.1242/dev.01966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll S, Garner W, Elder J. Heparin-binding ligands mediate autocrine EGF receptor activation in skin organ culture. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1271–1281. doi: 10.1172/JCI119641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll SW, Benedict M, Mitra R, Hiniker A, Elder JT, Nuñez G. EGF receptor signaling inhibits keratinocyte apoptosis: evidence for mediation by Bcl-XL. Oncogene. 1998;16:1493–1499. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll SW, Elder JT. Differential regulation of EGF-like growth factor genes in human keratinocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;265:214–221. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll SW, Kansra S, Elder JT. Metalloproteinases stimulate ErbB-dependent ERK signaling in human skin organ culture. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26839–26845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll SW, Kansra S, Elder JT. Keratinocyte outgrowth from human skin explant cultures is dependent upon p38 signaling. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2003;11:346–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2003.11506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll SW, Kansra S, Peshick S, Fry DW, Leopold WR, Wiesen JF, et al. Differential utilization and localization of ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase activities in intact skin compared to normal and malignant keratinocytes. Neoplasia. 2001;3:339–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan L, Murison JG, Prestidge RL, Sleeman MA, Watson JD, Kumble KD. Cloning and biological activity of epigen, a novel member of the epidermal growth factor superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18265–18271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumaru S, Higashiyama S, Endo T, Nakagawa T, Miyagawa JI, Yamamori K, et al. Ectodomain shedding of epidermal growth factor receptor ligands is required for keratinocyte migration in cutaneous wound healing. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:209–220. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani J, Zeigler M, Dame MK, Kang S, Fisher GJ, Voorhees JJ, et al. Heparin-binding-epidermal-growth factor-like growth factor activation of keratinocyte erbB receptors mediates epidermal hyperplasia, a prominent side effect of retinoid therapy. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1335–1341. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson KR, Lanning DA, Diegelmann RF, Spiegel S. Regulation of fibroblast functions by lysophospholipid mediators: potential roles in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:607–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmarth NE, Ethier SP. Autocrine and juxtacrine effects of amphiregulin on the proliferative, invasive, and migratory properties of normal and neoplastic human mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37728–37737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606532200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane S, Ishida S, Hanamoto Y, Kumagai K, Masuda R, Tanaka K, et al. Proinflammatory role of amphiregulin, an epidermal growth factor family member whose expression is augmented in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Inflamm (Lond) 2008;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki S, Iwamoto R, Saeki K, Asakura M, Takashima S, Yamazaki A, et al. Mice with defects in HB-EGF ectodomain shedding show severe developmental abnormalities. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:469–475. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]